Understanding Persistent Wage Disparities in Rural Colombia: Comparative Lessons from Latin America

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How large is the wage gap between rural coffee/cocoa workers and urban manufacturing workers, and has this gap changed over the past two decades?

- (2)

- To what extent can differences in worker characteristics (education, experience, etc.) explain the wage gap, and how much of the gap is due to other factors?

- (3)

- What policy lessons from other countries (e.g., Brazil, Mexico) can inform strategies to close the rural–urban wage gap in Colombia?

2. Literature Revision

2.1. Theoretical Perspectives: Rural–Urban Wage Gaps

2.2. Empirical Studies on Rural–Urban Wage Gaps

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data and Methodology

3.1.1. Data and Sample

3.1.2. Econometric Approach

β5*Children + β6*Contract + β7*Owner place + ε

log(β4*Gender) + log(β5*Children) + log(β6*Contract) + ln(β7*Owner place) + ε

4. Results

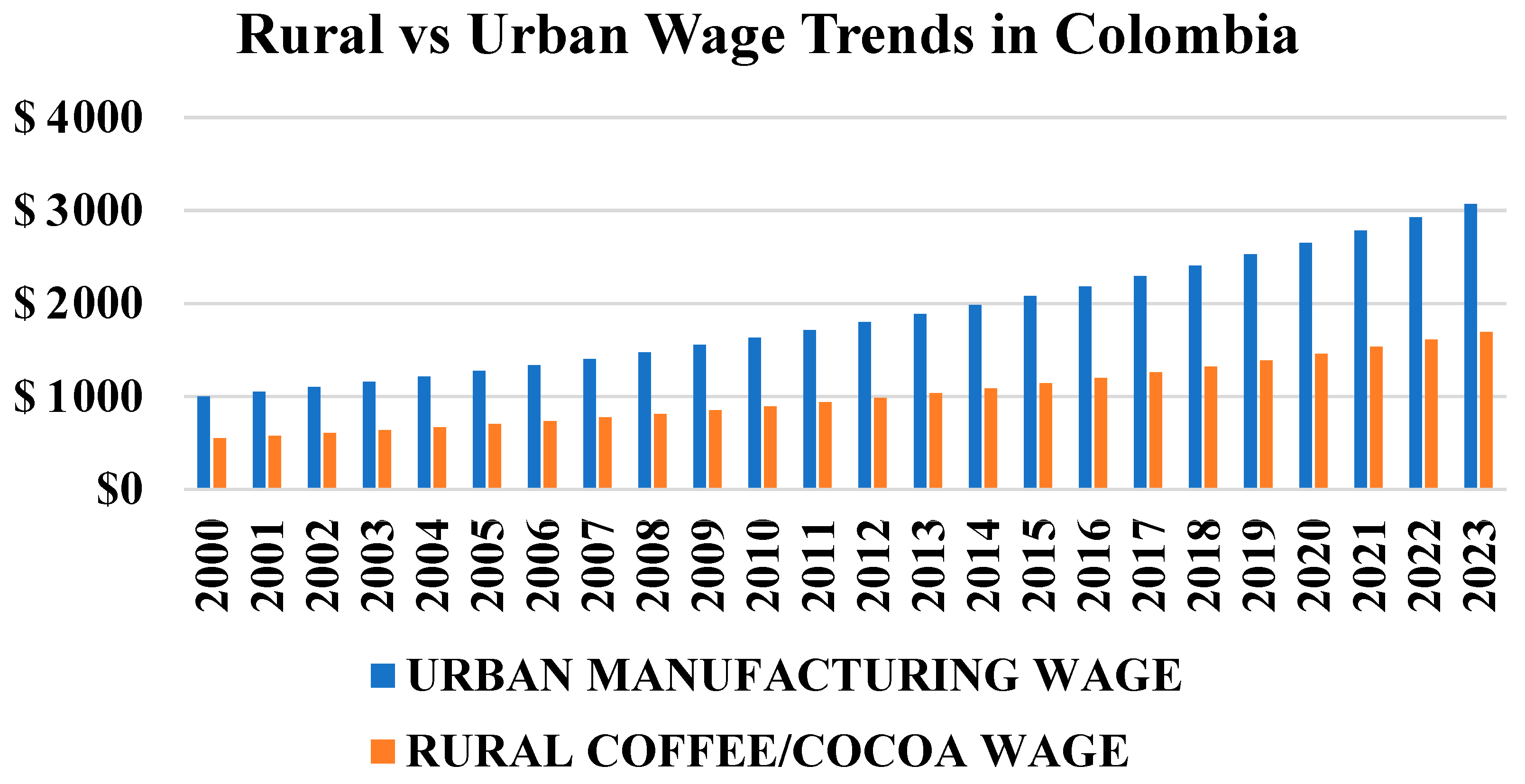

4.1. Descriptive Findings: Magnitude and Trends of the Wage Gap

4.2. Regression Results: Controlled Wage Differentials

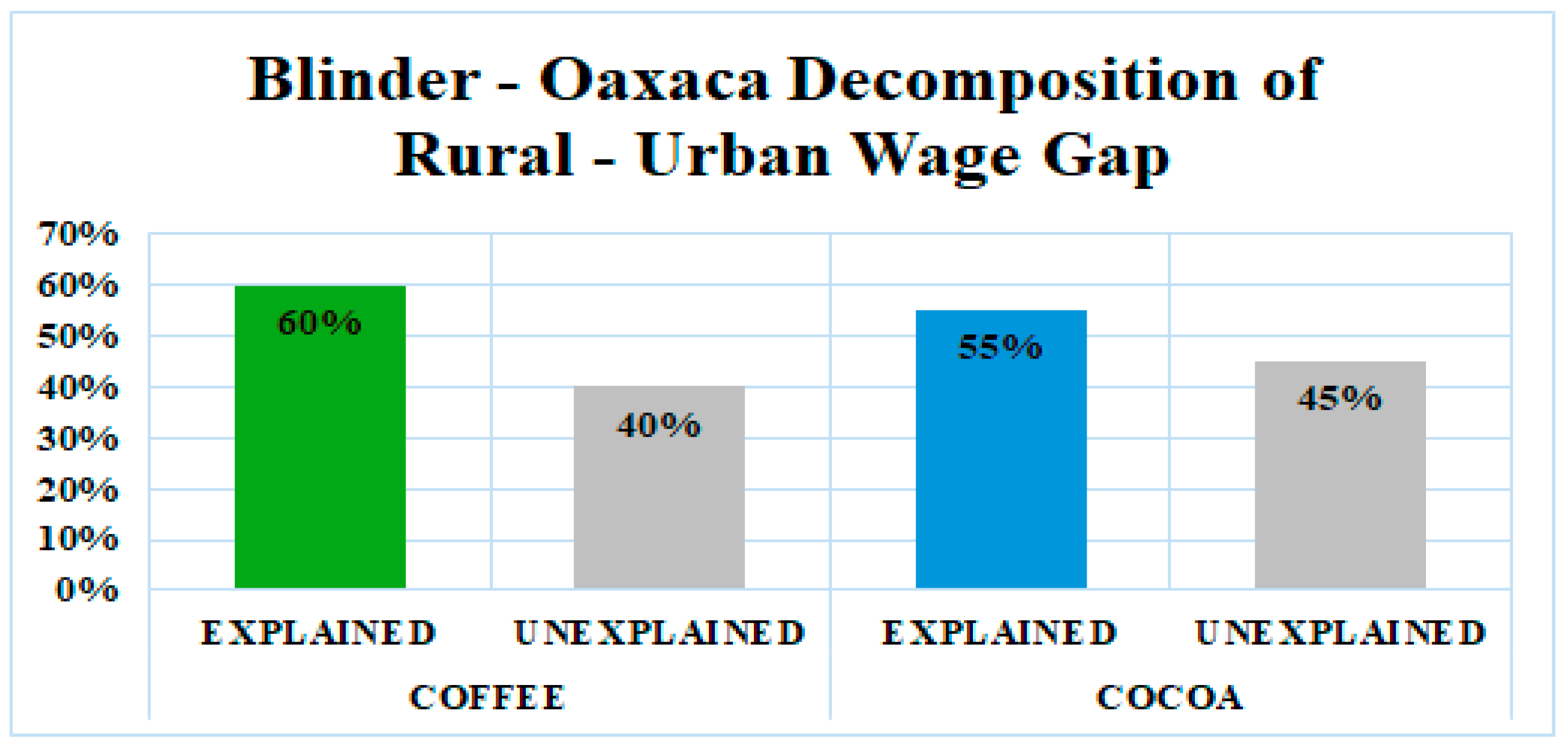

4.3. Decomposition Results: Explained vs. Unexplained Gap

4.4. Interpreting the Results in Light of Theory

5. Discussion

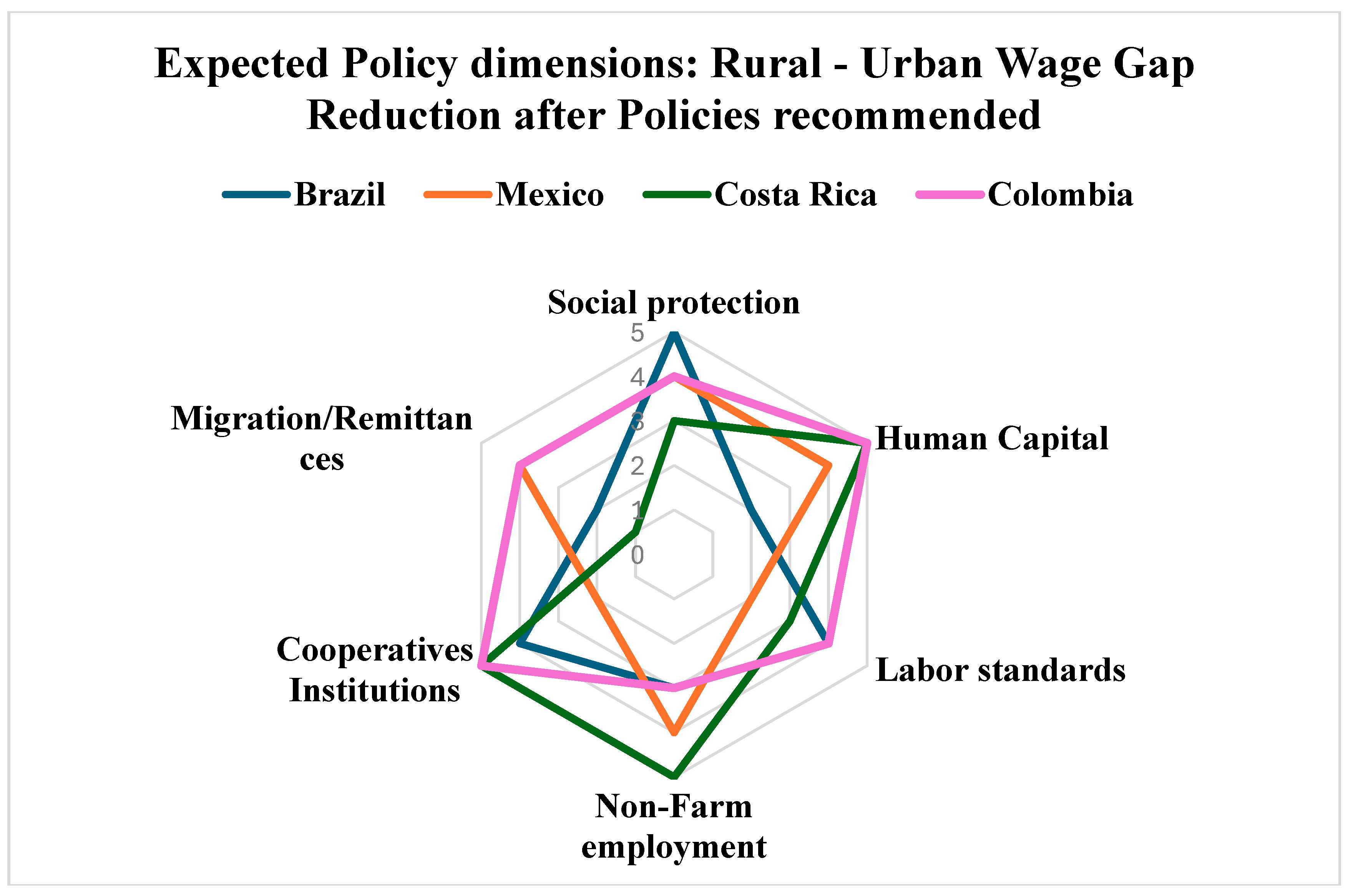

5.1. Comparative Perspectives: Lessons from Latin America

5.2. Brazil: Rural Social Protection and Agrarian Development

5.3. Mexico and Other Latin American Countries: Social Programs and Migration Dynamics

- ▪

- Social protection programs (pensions, cash transfers) can significantly alleviate rural poverty and indirectly support wages by raising reservation incomes.

- ▪

- Human capital investments (education, healthcare) in rural areas pay off in the long run, enabling rural residents to obtain better-paying jobs and be more productive.

- ▪

- Enforcement of labor standards (minimum wage, working conditions) in rural areas, though challenging, can help formalize rural employment and push wages upward (Brazil’s case).

- ▪

- Encouraging rural industries and value addition (e.g., processing agricultural products locally, developing rural service hubs) can provide alternative employment to absorb surplus labor at better wages.

- ▪

- Strengthening rural institutions such as cooperatives and farmer organizations can empower small producers and workers to find better terms from the market.

- ▪

- Facilitating migration can relieve labor pressure, but it is not a panacea—unchecked migration can lead to urban unemployment and does not raise rural wages for those left behind. The ideal is to create conditions where people are not forced to migrate out of desperation but migrate by choice.

5.4. Comparative Policy Dimensions: Radar Chart

6. Policy Implications for Colombia

- ▪

- Invest in Rural Education and Skills Training: Improving the quality and accessibility of education in rural areas is crucial. Higher educational attainment will enable rural workers (especially the youth) to be more productive and to access better-paying jobs, either in rural non-farm activities or in urban areas if they choose to migrate. Currently, lower education accounts for a significant portion of the wage gap. Policies should include increasing funding for rural schools, offering targeted scholarships for rural students, and expanding vocational training programs in agricultural communities. Evidence suggests that educational disparities contribute to wage disparities; thus, closing the education gap can gradually narrow the wage gap. Moreover, extension services and technical training for farmers can boost productivity and incomes on the farm. Over time, a more skilled rural workforce can demand higher wages and diversify into higher-value activities (Gáfaro and Pellegrina 2022; Chen et al. 2021).

- ▪

- Strengthen Labor Market Institutions and Wage Enforcement in Rural Areas: Colombia should work to enforce labor standards (such as minimum wage laws and social security coverage) for rural and agricultural workers. While challenging due to informality, incremental steps can be taken, such as formalizing labor contracts in larger farming enterprises and instituting wage boards or standard rates for certain agricultural tasks. Brazil’s experience showed that extending labor rights to rural workers (e.g., mandating formal contracts and benefits on large farms) helped lift rural wages. Colombia could introduce a rural minimum wage appropriate to regional productivity levels or strengthen the labor inspectorate to curb abusive practices. Even if not all rural jobs can be formalized immediately, setting normative wage guidelines (for instance, through local committees of the Ministry of Labor in farming regions) can empower workers to negotiate better pay. Reducing extreme exploitation is critical—when rural workers have no alternative and no legal protection, wages remain at a bare subsistence level. The International Labour Organization guidelines on wage-setting and equality recommend extending coverage to rural areas. As rural labor becomes better protected, the wage gap should reduce, though care must be taken to not simply drive employment to informality; thus, enforcement needs to go hand-in-hand with support for employers to increase productivity (so they can pay the higher wages) (Ananian and Dellaferrera 2024; IMF 2022; Chen et al. 2021; Barrientos 2003).

- ▪

- Expand Rural Social Protection (Non-contributory Pensions and Cash Transfers): Providing a basic income floor for rural households can raise the reservation wage and reduce poverty. A non-contributory rural pension (similar to Brazil’s) would allow older rural workers to retire with dignity and reduce the labor oversupply caused by elderly people continuing to work because they cannot afford to stop. If older workers exit the labor pool on a pension, younger workers may find it easier to bargain for better wages. Barrientos (2003) finds that pensions significantly reduced poverty in Brazil’s rural areas. Colombia could build on its recent pilot programs for rural minimum income for seniors. Additionally, conditional cash transfers like ‘Familias en Acción’ should be bolstered and targeted at the poorest rural regions, potentially with higher benefits to account for gaps. These transfers, as seen in Mexico’s Prospera, improve human capital and provide immediate poverty relief. While they do not directly raise market wages, they reduce the desperation that forces rural people to accept extremely low pay, effectively setting a floor under incomes. Over time, better-nourished, better-educated rural youth will be able to command higher wages. Expanding social protection is a direct way to address the welfare gap while indirectly influencing the labor market to not tolerate ultra-low wages (Murialdo 2023; World Bank 2022; IADB 2018; Haggblade et al. 2010; Barrientos 2003).

- ▪

- Promote Farmer Cooperatives and Market Access Initiatives: Organizing small farmers and rural workers into cooperatives or associations can increase their bargaining power and share in value addition. Cooperatives can help members obtain better prices for crops, reduce input costs, and even set up processing facilities. In contexts like Costa Rica and some Brazilian states, cooperatives have improved rural livelihoods. Colombia has some cooperatives (including in coffee through the National Federation of Coffee Growers), but encouraging more bottom-up cooperatives in cocoa and other sectors could enable farmers to pay themselves and any laborers more fairly. Additionally, facilitating access to higher-value markets—for instance, certifications for fair trade or organic coffee/cocoa—can allow producers to earn premium prices that translate into higher wages. If small producers receive a larger share of the final consumer price, they can afford to pay hired labor more. The International Labour Organization (ILO) has emphasized cooperatives as a tool for people-centered rural development, noting their role in empowering workers and improving incomes. Government support can include providing technical assistance to nascent cooperatives, start-up grants, or preferential credit. Over time, stronger rural organizations can also serve as channels to implement minimum wage agreements or profit-sharing in communities (ILO 2012, 2019, 2020; Cosar and Demir 2016; Cosar and Fajgelbaum 2016; Bernard et al. 2007).

- ▪

- Boost Agricultural Productivity and Value Addition: Low productivity in rural Colombia is a fundamental cause of low wages. Thus, policies that raise productivity can create room for higher wages without rendering farms non-viable. This includes investing in rural infrastructure such as roads, irrigation, storage facilities, and electrification. Better roads, for example, reduce the cost of transporting crops to market, raising the prices farmers receive. If farm revenues increase, there is more scope to increase wages for laborers. Rural road investments in other Latin countries have shown positive effects on local economies. The government should prioritize infrastructure projects in coffee and cocoa growing regions (some of which are remote and were affected by conflict). Alongside infrastructure, increasing access to finance and technology for small farmers will enable them to adopt improved seeds, fertilizers, or new crops, thus increasing output. Government programs or public–private partnerships could facilitate affordable credit and insurance for smallholders. A more productive agricultural sector can support higher labor costs. It is also important to diversify and add value: for instance, encouraging local processing of cocoa into chocolate, or coffee into roasted beans, rather than exporting raw commodities. The government could provide incentives (tax breaks, subsidies) for establishing processing facilities in secondary towns of coffee/cocoa regions. This would create better-paying jobs in rural areas (e.g., a job in a chocolate factory pays more than picking cocoa pods) and reduce the need for workers to migrate to cities. Such agro-industrialization has been part of rural development strategies in countries like Mexico (where programs tried to entice maquiladora factories to smaller towns) and can help integrate rural populations into higher value chains (Gáfaro and Pellegrina 2022; Chen et al. 2021; Benguria et al. 2021; OECD 2020; IADB 2018; Haggblade et al. 2010; ILO 2020).

- ▪

- Facilitate Orderly Migration and Urban Integration: While the goal is to improve rural conditions so that migration is by choice rather than necessity, migration will continue to be a reality. Policymakers should ensure that those who do migrate have pathways to decent urban employment (for example, through training programs that target rural youth for urban skills, or urban job placement services). This can prevent a scenario where migrants simply swell the ranks of urban informal workers, which maintains the Harris–Todaro equilibrium. If rural migrants can more quickly secure formal jobs in cities, the expected income gap would narrow, and migration flows would balance. Additionally, rural development efforts in conflict-affected zones (now under the Peace Accord’s rural reform) need to be accelerated, as peace and security are prerequisites for any economic initiative to thrive. Reducing violence and improving land governance will make other interventions more effective (Taylor and Martin 2001; Harris and Todaro 1970).

Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamopoulos, Tasso, and Diego Restuccia. 2014. The size distribution of farms and international productivity differences. American Economic Review 104: 1667–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, Tasso, and Diego Restuccia. 2020. Land reform and productivity: A quantitative analysis with microdata. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 12: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamopoulos, Tasso, Loren Brandt, Jessica Leight, and Diego Restuccia. 2022. Misallocation, Selection, and Productivity: A Quantitative Analysis with Panel Data From China. Econometrica 90: 1261–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T. 2014. Information friction in trade. Econometrica 82: 2041–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Treb, and David Atkin. 2015. Volatility, Insurance, and the Gains from Trade. Econometrica 90: 2053–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminur, Rahman. 2025. Why Is the Evolution of Urban-Rural Wage Disparities in Bangladesh Slow. International Journal of Accounting and Economics Studies 12: 1073–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananian, Sévane, and Giulia Dellaferrera. 2024. Employment and Wage Disparities Between Rural and Urban Areas. ILO Working Paper No. 107. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Kym, Gordon Rausser, and Johan Swinnen. 2013. Political Economy of Public Policies: Insights from Distortions to Agricultural and Food Markets. Journal of Development Economics 103: 154–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkolakis, Costas. 2010. Market penetration costs and the new consumers margin in international trade. Journal of Political Economy 118: 1151–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila, Antonio Flavio Dias, and Robert E. Evenson. 2010. Total factor productivity growth in agriculture: The role of technological capital. Handbook Agriculture Economics 4: 3769–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, Armando. 2003. What Is the Impact of Non-Contributory Pensions on Poverty? Estimates from Brazil and South Africa. Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper 33. Manchester: University of Manchester. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1754420 (accessed on 9 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, Armando, and David Hulme. 2009. Social Protection for the Poor and Poorest in Developing Countries: Reflections on a Quiet Revolution. Oxford Development Studies 37: 439–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, Robert J. 1991. Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics 106: 407–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, Robert J., and Xavier Sala-i-Martin. 1992. Convergence. Journal of Political Economy 100: 223–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, Nathaniel. 2007. Did highways cause suburbanization? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 775–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum-Snow, Nathaniel, Loren Brandt, J. Vernon Henderson, Matthew A. Turner, and Qinghua Zhang. 2017. Roads, railroads, and decentralization of Chinese cities. The Review of Economics and Statistics 99: 435–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benguria, F., Felipe Saffle, and Sergio Urzúa. 2021. The Transmission of Commodity Price Super-Cycles. National Bureau of Economic Research, Issue Date: April 2018, Revision Date January 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3170797 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Bernard, Andrew B., J. Bradford Jensen, Stephen J. Redding, and Peter K. Schott. 2007. Firms in international trade. Journal of Economic Perspectives 21: 105–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, Alan S. 1973. Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural Estimates. The Journal of Human Resources 8: 436–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, Gharad, and Melanie Morten. 2019. The aggregate productivity effects of internal migration: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Political Economy 127: 2229–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, Lorenzo, Fernando Parro, Esteban Rossi-Hansberg, and Pierre-Daniel Sarte. 2018. The impact of regional and sectoral productivity changes on the us economy. The Review of Economic Studies 85: 2042–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, Thomas. 2008. Distorted gravity: The intensive and extensive margins of international trade. American Economic Review 98: 1707–21. Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.98.4.1707 (accessed on 9 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chaoran, Diego Restuccia, and Raül Santaeulàlia-Llopis. 2021. The effects of land markets on resource allocation and agricultural productivity. Review of Economic Dynamics 45: 1094–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, Shyamal K., Ashok Gulati, and E. Gumbira-Sa’id. 2005. The rise of supermarkets and vertical relationships in the Indonesian food value chain: Causes and consequences. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Development 2: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosar, Kerem, and Banu Demir. 2016. Domestic road infrastructure and international trade: Evidence from Turkey. Journal of Development Economics 118: 232–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosar, Kerem, and Pablo D. Fajgelbaum. 2016. Internal geography, international trade, and regional specialization. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 8: 24–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costinot, Arnaud, Dave Donaldson, and Cory Smith. 2016. Evolving comparative advantages and the impact of climate change in agricultural markets: Evidence from 1.7 million fields around the world. Journal of Political Economy 124: 205–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuecuecha Mendoza, A., N. Fuentes Mayorga, and Darryl McLeod. 2021. Do minimum wages help explain declining Mexico-U.S. migration? Migraciones Internacionales 12: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Christopher, Jane Hopkins, Valerie Kelly, Peter Hazell, Anna A. McKenna, Peter Gruhn, Behjat Hojjati, Jayashree Sil, and Claude Courbois. 1998. Agricultural Growth Linkages in Sub-Saharan Africa. IFPRI Research Report 107. Washington, DC: IFPRI. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/5056928_Agricultural_Growth_Linkages_in_Sub-Saharan_Africa (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Fajgelbaum, Pablo, and Stephen J. Redding. 2021. Trade, Structural Transformation and Development: Evidence from Argentina 1869–1914 Working Paper. National Bureau of Economic Research 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, Ma 02138 June 2014, Revised September 2021. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w20217 (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- FAO. 2020. The State of Food and Agriculture 2020. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. Available online: https://www.fao.org/interactive/state-of-food-agriculture/2020/en/ (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Foster, Andrew, and Mark R. Rosenzweig. 2022. Are there too many farms in the world? Labor-market transaction costs, machine capacities and optimal farm size. Journal of Political Economy 130: 636–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, Catalina, and Johanna Ramos. 2010. Diferenciales Salariales en Colombia: Un Análisis para Trabajadores Rurales y Jóvenes, 2002–2009. Revista de Análisis Económico 25: 91–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gáfaro, Margarita, and Heitor S. Pellegrina. 2022. Trade, Farmers’ Heterogeneity, and Agricultural Productivity: Evidence from Colombia. Journal of International Economics 137: 103598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggblade, Steven, Peter Hazell, and Thomas Reardon. 2010. The Rural Non-Farm Economy: Prospects for Growth and Poverty Reduction. World Development 38: 1429–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Jone R., and Michael P. Todaro. 1970. Migration, Unemployment, and Development: A Two-Sector Analysis. American Economic Association 60: 126–42. Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/aer/top20/60.1.126-142.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Hataya, Noriko. 1992. Urban-Rural Linkage of the Labor Market in the Coffee Growing Zone in Colombia. Published: March 1992. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1746-1049.1992.tb00004.x (accessed on 11 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, Jill E., and Linda M. Young. 2000. Closer vertical co-ordination in agri-food supply chains: A conceptual framework and some preliminary evidence. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 5: 131–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IADB. 2018. Social Protection and Labor in Latin America. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/en (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2012. Cooperatives for People-Centred Rural Development. Geneva: ILO. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/cooperatives/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2019. Employment and WageDisparities Between Rural and Urban Areas. Geneva: ILO. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/employment-and-wage-disparities-between-rural-and-urban-areas (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2020. World Employment and Social Outlook. Geneva: ILO. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/@publ/documents/publication/wcms_734455.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). 2022. Regional Economic Outlook: Western Hemisphere. Washington, DC: IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/REO/WH/Issues/2022/04/19/regional-economic-outlook-western-hemisphere-april-2022 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Kadjo, Didier, Jacob Ricker-Gilbert, Gerald Shively, and Tahirou Abdoulaye. 2019. Food Safety and Adverse Selection in Rural Maize Markets. Journal of Agricultural Economics 71: 412–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibovich, José, Mario Nigrinis, and Mario Ramos. 2007. Caracterización del mercado laboral rural en Colombia, Copyright 2018 Revista del Banco de la República, septiembre de 2006, Volumen 79, Número 947 (2006) Páginas 15 a 76. Available online: https://publicaciones.banrepcultural.org/index.php/banrep/article/view/9630/10025 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Lewis, W. Arthur. 1954. Economic Development with an Unlimited Supply of Labour. The Manchester School 22: 139–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Mingming, Yuan Tang, and Keyan Jin. 2024. Labor market segmentation and the gender wage gap: Evidence from China. PLoS ONE 19: e0299355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaelsen, Maren M., and John P. Haisken De-New. 2011. Migration Magnet: The Role of Work Experience in Rural-Urban Wage Differentials in Mexico. Ruhr Economic Paper 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mincer, Jacob. 1974. Schooling, Experience, and Earnings. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: https://www.nber.org/books-and-chapters/schooling-experience-and-earnings (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Moffitt, Robert. 1983. An Economic Model of Welfare Stigma. American Economic Review 73: 1023–35. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:aea:aecrev:v:73:y:1983:i:5:p:1023-35 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Murialdo, Melissa. 2023. More Than 10 Million Colombians Continue to Work in the Informal Economy. Finance Colombia. Available online: https://www.financecolombia.com/more-than-10-million-colombians-continue-to-work-in-the-informal-economy/ (accessed on 9 August 2025).

- Nguyen The Kang. 2025. The impact of agricultural and service sector output on economic growth in Vietnam. International Journal of Innovative Research and Scientific Studies (IJIRSS) 8: 3473–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ñopo, Hugo, Nancy Daza, and Johanna Ramos. 2012. Gender Earning Gaps around the World: A Study of 64 Countries. International Journal of Manpower 33: 464–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaxaca, Ronald. 1973. Male–Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets. International Economic Review 14: 693–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2020. Rural Well-Being: Geography of Opportunities. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-Cortés, Andrea, and Edson Acosta-Ariza. 2022. Desigualdades en el mercado laboral urbano-rural en Colombia, 2010–2019. Revista CS, 173–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G. 2020. Rural Roads: Key Routes for Production, Connectivity and Territorial Development. FAL Bulletin No. 1/2020. Santiago de Chile: ECLAC. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/en/publications/45865-rural-roads-key-routes-production-connectivity-and-territorial-development (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Rodríguez Castelán, Carlos, Daniel Felipe Valderrama, Luis F. Lopez-Calva, and Nora Lustig. 2016. Understanding the Dynamics of Labor Income Inequality in Latin America. August 2016. Affiliation: World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 7795. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317077134_Understanding_the_Dynamics_of_Labor_Income_Inequality_in_Latin_America (accessed on 12 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, Paul R., and Donald B. Rubin. 1983. The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects. Biometrika 70: 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahe, Emran, and Shilpi Forhad. 2017. Agricultural Productivity, Hired Labor, Wages, and Poverty: Evidence from Bangladesh. World Development 109: 470–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R. Paul. 1974. A Conceptual Model of Rural-Urban Transition and Reproductive Behavior. Rural Sociology 39: 70. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Ziheng. 2023. Disparity in Educational Resources Between Urban and Rural Areas in China. Journal of Advanced Research in Education 2: 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanohashi, Marcos, Marcel Ribeiro, and Friedrich Schneider. 2025. The impact of inequality on the informal economy in Latin America and Caribbean with a MIMIC model. Empirical Economics 69: 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. Edward, and Philip L. Martin. 2001. Human Capital: Migration and Rural Population Change. In Handbook of Agricultural Economics 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 457–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, Michael P. 1969. A Model of Labor Migration and Urban Unemployment in Less Developed Countries. The American Economic Review 59: 138–48. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1811100 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Wang, Sophie Xuefei, and Benjamin Yu. 2018. Labor mobility barriers and rural-urban migration in transitional China. China Economic Review 53: 211–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2008. Inequality in Latin America: Determinants and Consequences. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2017. Wage Inequality in Latin America: Understanding the Past to Prepare for the Future. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2020. Productive Inclusion in Latin America: Policy and Operational Lessons. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/34199 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- World Bank. 2021. Breaking Barriers—Disability Inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2022. Colombia Systematic Country Diagnostic. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/427121628408937462/colombia-systematic-country-diagnostic (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- World Bank. 2023. World Development Indicators (WDI). Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Xi, Tang. 2023. Educational Inequality Between Urban and Rural Areas in China. Lecture Notes in Education Psychology and Public Media 30: 293–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Xiliang. 2020. Migrants and urban wage: Evidence from China’s internal migration. China Economic Review 61: 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sector & Location | Average Hourly Wage (COP) | Rural Wage as % of Urban |

|---|---|---|

| Urban Manufacturing Workers | 5.000 | - |

| Rural Coffee Farm Workers | 2.500 | 50% |

| Rural Cocoa Farm Workers | 2.300 | 46% |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (COP) | 8781.75 *** | 4597.04 *** | 4333.96 *** | 4243.73 *** |

| Agricultural sector (1 if rural coffee/cocoa worker) | −3684.61 *** | −1260.31 *** | −1162.41 *** | −1146.77 *** |

| Age (years) | 24.33 *** | 24.66 *** | 20.59 *** | |

| Education (years) | 108.16 *** | 107.71 *** | 104.79 *** | |

| Female (1 = yes) | −464.05 ** | −447.81 ** | −423.69 ** | |

| Children < 6 yrs | 54.46 | 34.72 | – | |

| Has formal contract (1 = yes) | 254.76 * | 528.68 *** | – | |

| Owns land/farm (1 = yes) | 867.86 *** | – | – | |

| R2 | 0.0383 | 0.0197 | 0.0204 | 0.0236 |

| Observations | 5236 | 5057 | 5057 | 5057 |

| Variable | Model 1 (log) | Model 2 (log) | Model 3 (log) | Model 4 (log) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 8.8701 *** | 8.5458 *** | 8.3591 *** | 8.3567 *** |

| Agricultural sector (1 if rural coffee/cocoa worker) | −0.4911 *** | −0.3308 *** | −0.2509 *** | −0.2505 *** |

| Age (years) | 0.0021 *** | 0.0021 *** | 0.0020 *** | |

| Education (years) | 0.0139 *** | 0.0135 *** | 0.0134 *** | |

| Female (1 = yes) | −0.1798 *** | −0.1649 *** | −0.1643 *** | |

| Children < 6 yrs | 0.0047 | 0.0041 | – | |

| Has formal contract (1 = yes) | 0.1975 *** | 0.2050 *** | – | |

| Owns land/farm (1 = yes) | 0.0236 | – | – | |

| R2 | 0.0790 | 0.0635 | 0.0996 | 0.0998 |

| Observations | 5236 | 5057 | 5057 | 5057 |

| Variables | Average Group 1 (Agricultural) | Average Group 0 (Non-Agricultural) | Group 0 Beta | Group 1 Beta | Explained Portion | Unexplained Portion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.86691312 | 34.81775701 | 0.005788171 | 0.006808568 | 0.046589891 | 0.043741294 |

| Education | 5.768396846 | 13.86192469 | 0.004897276 | 0.015269325 | −0.039636239 | 0.059830094 |

| Gender Female | 0.080134827 | 0.400934579 | −0.147759374 | −0.012073062 | 0.047401171 | 0.010873199 |

| Children< 6 yrs | 0.286071545 | 0.288785047 | −0.145641722 | −0.044821412 | 0.000395199 | 0.028841822 |

| Contract | 0.486571708 | 0.887850467 | 0.423313843 | 0.153878612 | −0.169866853 | −0.131099561 |

| TOTAL | 8.04364681 | 8.531353927 | −0.115116831 | 0.012186848 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moncada Aristizábal, J.A.; Cala Vitery, F. Understanding Persistent Wage Disparities in Rural Colombia: Comparative Lessons from Latin America. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120677

Moncada Aristizábal JA, Cala Vitery F. Understanding Persistent Wage Disparities in Rural Colombia: Comparative Lessons from Latin America. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(12):677. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120677

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoncada Aristizábal, José Alejandro, and Favio Cala Vitery. 2025. "Understanding Persistent Wage Disparities in Rural Colombia: Comparative Lessons from Latin America" Social Sciences 14, no. 12: 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120677

APA StyleMoncada Aristizábal, J. A., & Cala Vitery, F. (2025). Understanding Persistent Wage Disparities in Rural Colombia: Comparative Lessons from Latin America. Social Sciences, 14(12), 677. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14120677