Abstract

Community-based organizations are recognized as key stakeholders for public health, as their community expertise positions them to create tailored interventions to comprehensively address community needs that large-scale public health interventions may not address. The current study describes one youth-serving community-based non-profit’s approach to public health, where youth civic engagement is oriented by social justice coursework and integrated within youth participatory action research (YPAR) to engage youth in health equity efforts. The Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) framework and the Socioecological Model (SEM) were applied to student research outputs to understand student conceptualization of social issues and the subsequent interventions they suggest. This work explores the feasibility and depth of student-created interventions within each SDOH domain, identifying common themes in students’ conceptualizations of social problems and interventions to promote health equity. Suggestions for integrating SDOH frameworks into the YPAR curriculum to scaffold youth projects, identifying root causes of health disparities, and developing practical community-based solutions are provided.

1. Introduction

Health disparities remain a significant public health challenge, at both national and local levels, attributable to their detrimental effects on individual health outcomes (Tiwari 2024). Health disparities can affect individuals from diverse social, economic, and geographic backgrounds, and negatively impact quality of life and wellbeing (Whitman et al. 2022). However, health disparities are created and supported by inequitable systems and an unequal distribution of resources and opportunities, leading to disproportionate effects that significantly impact the quality of life of all marginalized populations (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine et al. 2017). This effect is further exacerbated for those with intersectional identities, where multiple layers of vulnerability and marginalization overlap to produce distinct health outcomes that require tailored interventions, specifically for those identifying as Black, female, LGBTQ+, and/or low-income (Hill 2015; Lett et al. 2020).

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) encompass a wide range of factors that influence the conditions under which an individual develops across time, including economic stability; access to quality healthcare, education, and nutritious foods; and community and social contexts (Whitman et al. 2022). Experts in the field suggest that addressing factors of the SDOH are particularly crucial to increasing the overall wellbeing of marginalized populations, where SDOH have been shown to drive and produce health disparities (Chelak and Chakole 2023). As a result, a wide range of public health interventions have been developed at the national and regional levels to adequately address the health needs of marginalized populations (Whitman et al. 2022). While large-scale public health intervention efforts have significant positive effects on multiple dimensions of health outcomes, they often lack the ability to tailor interventions to meet the unique needs and barriers to health equity within diverse communities (American Public Health Association 2022). Considering community-based organizations in public health interventions is necessary to comprehensively address health disparities for marginalized individuals in local contexts (Haapanen et al. 2024).

Community-based, grassroots organizations are particularly well equipped to address the specific needs of their community and often work to address health disparities, promoting missions like providing quality educational youth programs, increasing access to affordable healthcare, promoting community engagement, and connecting families to community resources, among others (Griffith et al. 2010; Miller and Shinn 2005). Furthermore, community-based organizations have distinct strengths that set them apart from large-scale interventions; (1) all members of the community tend to have access to services, and not just a select group, (2) community-based organizations can reach individuals of various risk-levels, and not just those who are high-risk, and (3) community-based organizations can address environmental and social conditions that are often difficult to reach with more national-level interventions (Institute of Medicine et al. 2012). These community-based entities play a critical role in reducing health disparities and providing community members with essential resources to aid in their quality of life and ultimately influence their health outcomes (Ressler et al. 2021). Non-profit organizations are important public health stakeholders, where they are able to leverage their cultural insights to create targeted public health interventions for their community members (Tiwari 2024).

Community-based organizations that develop and implement public health interventions have community expertise and in-depth knowledge of the existing resources and organizations that exist to support the health needs of the community (Baciu et al. 2017). As a result, community-based organizations can use their positioning to develop partnerships and connect community members to services that adequately address their needs (Allen et al. 2021). Furthermore, community-based organizations can draw upon these partnerships to create youth–organization collaborative networks, promoting youth civic engagement and creating stewards of change (McLean 2019). One unique experience that community-based organizations can provide for young people to be active change agents within their community is youth participatory action research (YPAR).

YPAR, a research methodology that positions youth as experts, orients youth toward critically examining social issues relevant to their lives through rigorous research methodologies and developing creative solutions to positively impact the world around them (Malorni et al. 2022). YPAR provides a platform to privilege and uplift youth voices in conversations around health equity, where they have been shown to be key community stakeholders and creative thinkers who can create unique solutions to local, community-based social issues (Anyon et al. 2018; Ozer et al. 2020). YPAR frameworks are often guided by social justice principles, which supports youth in developing solutions to address the root causes of health inequities but does not directly support youth in identifying the root cause of these inequities. One novel approach to extend students’ abilities to contribute to the process of uncovering root causes of health disparities is integrating the SDOH framework within YPAR curriculum, which provides youth with a comprehensive framework to understand and investigate various factors that influence inequitable outcomes.

1.1. Theoretical Frameworks

SDOH are environmental conditions that individuals inhabit throughout their life that affect health and quality-of-life outcomes, such as education, infrastructure, healthcare, economics, and community context (WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health and World Health Organization 2008). The SDOH framework allows us to gain a deeper understanding of the complex interplay of risk and protective factors that contribute to health disparities, particularly for those from lower socioeconomic statuses, racial and economic minorities, and those with disabilities (WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health and World Health Organization 2008). The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (n.d.) identified five key SDOH domains that influence health outcomes: economic stability, education access and quality, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context.

Economic stability refers to factors related to financial security, where socio-economic status directly influences the quality of food, housing, healthcare, and employment opportunities one has access to, impacting health outcomes across multiple domains. Education access and quality include factors like literacy levels and educational attainment, where access to quality educational opportunities and the ability to engage in these opportunities further influence economic stability and other health outcomes. Healthcare access and quality involve an individual’s ability to physically and financially access healthcare, the quality of care one has access to, and health literacy, which directly impacts an individual’s quality of life. Neighborhood and built environment affect health outcomes through aspects of the physical environments individuals inhabit, including community safety and violence, air and water quality, and access to recreational facilities. Social and community context refers to the complex network of relationships that influence an individual’s wellbeing through community connectedness, discrimination, and support networks (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion n.d.). Each domain is intricately related, where unique combinations of risk factors across all five domains frequently influence individual health outcomes, requiring the development of multi-tiered and multi-faceted public health interventions to achieve health equity (Bigby 2011; Horowitz and Lawlor 2008).

The Socioecological Model (SEM) extends the SDOH framework, positing that individual health behavior is influenced by complex factors that are nested within different micro and macro levels, including individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and policy levels (Bronfenbrenner 1977; Sallis and Owen 2015). The individual level encompasses individual level characteristics, including knowledge and attitudes, that influence health behavior (McLeroy et al. 1988). The interpersonal level represents an individual’s interaction with their social networks, friends, and family that have the potential to affect health and health-related decision making (Agnew and South 2014). The institutional level refers to the overarching environments social relationships take place within, including the characteristics and structure of workplaces, schools, and organizations (McLeroy et al. 1988). The community level describes the resources, institutions, social networks, and norms that comprise a neighborhood or city in which individuals live (Stokols 1996). The policy level includes federal, state, and local laws that directly influence access to and the utilization of healthcare services (Sallis and Owen 2015). These various levels provide a guide to understand the different societal levels interventions can occur at, best align interventions with outcomes of interest, and further support the criticality of multi-leveled and multi-faceted interventions to improve health outcomes (Golden and Earp 2012).

The SDOH and SEM frameworks guide the analysis of the current study. The SDOH framework was applied to student YPAR projects to understand how youth conceptualize social problems, apply solutions informed by their research, and align their interests with their coursework. The SEM framework was applied to understand the depth and breadth of student-developed interventions to various social issues. The organizational and programmatic context of students engaged in YPAR coursework is described below.

1.2. Youth Enrichment Services

1.2.1. Organizational Context

Youth Enrichment Services (YES), a community-based non-profit in Pittsburgh, strives to empower youth to become their own best resource. Offering multiple opportunities such as mentorship, education, and enrichment programs, YES opens its doors to any young person who could benefit from its resources, upholding the notion that there are no throwaway children. Over the past 30 years, YES has served over 6000 young people, where their community expertise was adapted to meet the diverse needs of youth over time.

YES equips students with the tools to be their own best resource through programs that support positive youth development and provide students with holistic support to address various needs. YES offers life skills development, cultural and social enrichment, and wellness initiatives through various program opportunities. One program highlighted within the current study, the YESSummer Learn and Earn program, is a youth employment program that offers extended opportunities to develop their academic, social/emotional, and research capacities. Students have the opportunity to participate in workshops and activities that enhance employability and workability, programs that help students prepare for college, and wellness initiatives that focus on self-care, financial independence, physical fitness, and spirituality. Furthermore, students participate in youth participatory action research (YPAR) alongside social justice coursework to build their critical thinking skills, demonstrate research acumen, and create experiences that are meaningful during the college application process.

1.2.2. Summer Study for Success

Summer Study for Success is one component of YES’Summer Learn and Earn program. A total of five courses were offered, informed by the SDOH, including Beyond the Block: Environmental Climate Justice, Good to Go: Health Justice, More than Money: Economic Justice, The Stories We Share: Justice in the Arts, and The Success Setup: Educational Justice. In Beyond the Block: Environmental Climate Justice, students learn the importance of advocacy and activism to address environmental threats. In Good to Go: Health Justice, students explore the importance of health literacy and its relevance among all healthcare stakeholders. In More Than Money: Economic Justice, students learn how the economy critically affects the stability and efficacy of communities, and specifically marginalized individuals. In The Stories We Share: Justice in the Arts, students explore how powerful art is when used as a mechanism for justice. In Success Setup: Educational Justice, students identify how current policies and educational structures can impact “dreams deferred.” Table 1 provides a full description of the course offerings and their alignment with the SDOH framework.

Table 1.

Course description and SDOH alignment.

Within Summer Study for Success, students gained a plethora of skills, knowledge, and experiences. Students learned how to utilize different research and data collection methods to better aid in the project research process, such as survey creation, to gather information about their topic. Students also gained data analytic skills which they used to understand how the data they collected could support justice-based advocacy efforts. To present their findings, students developed infographics and creative outputs, such as poems, short films, photography, and newsletters. Summer Study for Success allowed students to uniquely learn about the research process through a justice-centered lens.

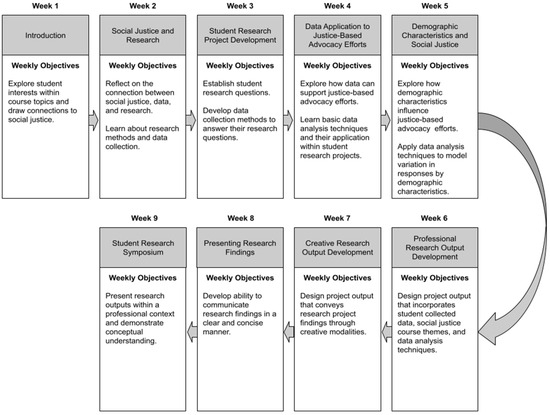

Overall, Summer Study for Success supported student knowledge development of social justice-related topics and the negative implications of health inequities on society. Such a program also impacted how youth perceived themselves as community change agents and thought about their roles as catalysts for health behavior change within neighborhood contexts (Youth Enrichment Services 2024). A course overview with the session sequence and weekly objectives is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of Summer Study for Success curriculum sequence.

1.3. Current Study

YES, a community-based non-profit in Pittsburgh, developed a summer learning program that utilizes the SDOH and Moncloa and Smith’s (2018) Social Justice Youth Development framework to inform YPAR projects. Summer Study for Success, integrated within YES’ summer youth employment program, is a joint social justice learning lab and YPAR program that incorporates student-centered learning to support skill development, sparks students’ interests and passions, and promotes active learning. In an effort to explore how youth voices can inform local public health interventions, this case study leverages YPAR project outputs to explore the following research questions: (1) What public health disparities and interventions are students interested in, and how do they vary across SDOH domains? (2) How can community-based organizations best support youth in becoming key changemakers in their community? Student project artifacts are analyzed using the SDOH and SEM frameworks, where their contributions as key community stakeholders are discussed.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The Summer Study for Success program was one component of YES’ summer youth employment program in Pittsburgh. Instructors were recruited from University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon University, and Pittsburgh Area High Schools and were compensated by a stipend. Of the 5 instructors who taught the classes, the highest level of education completed were master’s degrees (n = 2) and bachelor’s degrees (n = 3).

Of the 109 students in YES’ Summer Learn and Earn program, 70 participated in Summer Study for Success. Students within YES’Summer Learn and Earn who did not participate in Summer Study for Success were frequently involved in other program experiences or had availability conflicts that prevented engagement in academic enrichment programming. Students were recruited from Pittsburgh Public Schools and the surrounding areas, including middle and high schools, and were compensated hourly for sessions attended. Students participated in one course over the summer, where student placements were based upon student preference ratings. Student enrollment varied by course as follows: Beyond the Block: Environmental Climate Justice (n = 13), Good to Go: Health Justice (n = 15), More than Money: Economic Justice (n = 13), The Stories We Share: Justice in the Arts (n = 16), and The Success Setup: Education Justice (n = 13). Student grade levels ranged from 8th to 11th grade, where the majority of students attended 9th grade (35.71%, n = 25) and 10th grade (31.43%, n = 22). Student ages ranged between 14 and 19 (M = 15.91 years, SD = 1.09). Students’ gender status included 52.86% male-identifying individuals (n = 37), 45.71% female-identifying individuals (n = 32), and 1.43% non-binary individuals (n = 1). Overall, the majority of students were Black or African American (88.57%, n = 62), while four students identified as multiracial (5.71%); two students identified as other (2.86%), and one student chose not to disclose (1.43%).

2.2. Procedure

Summer Study for Success was implemented over the course of eight weeks, where students attended learning labs twice a week for three hours each, totaling six hours a week, where they worked in groups of two to three students on a research project of their choice. The learning lab culminated in a gallery style research symposium where students presented their infographics. The SDOH framework was applied post hoc to their research infographics to understand student perceptions of social problems and identify common themes across student projects. While student projects may have encompassed elements across multiple SDOH domains, each project was assigned one domain that best aligned with the project topic to allow for high-level comparison across participants. To further assess the depth and breadth of each project’s student-developed solution, the SEM framework was applied to define the intervention level (i.e., individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, policy) at which each solution was intended to intervene. Each student group designed and employed various data collection methodologies, where they recruited participants from a variety of settings and demographic backgrounds to participate in their study. However, the majority of student projects leveraged convenience samples within YES students and staff or members of their community to participate in their studies.

3. Results

Student projects (N = 24) focused on a wide variety of social issues that varied in alignment with the SDOH domains, including eight projects within social and community context (33.33%), five projects within education access and quality (16.67%), four within healthcare access and quality (20.83%), five within neighborhood and built environment (20.83%), and two within economic stability (8.33%). Overall, students identified solutions to their social problem at a variety of intervention levels, including individual (n = 1, 4.17%), interpersonal (n = 1, 4.17%), institutional (n = 5, 20.83%), community (n = 2, 8.33%), policy (n = 4, 16.67%), and multilevel (n = 5, 20.83%). Six students did not identify a solution to their social problem (25%), which is reflective of flexibility in what sections each presentation included and not of the addressability of the social problem students identified. Student-project topics and their proposed intervention level are organized by SDOH domain below. Full descriptions of student projects, including their findings, proposed solutions, and SDOH domain alignment and intervention level, are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Student project description and SDOH alignment (N = 24).

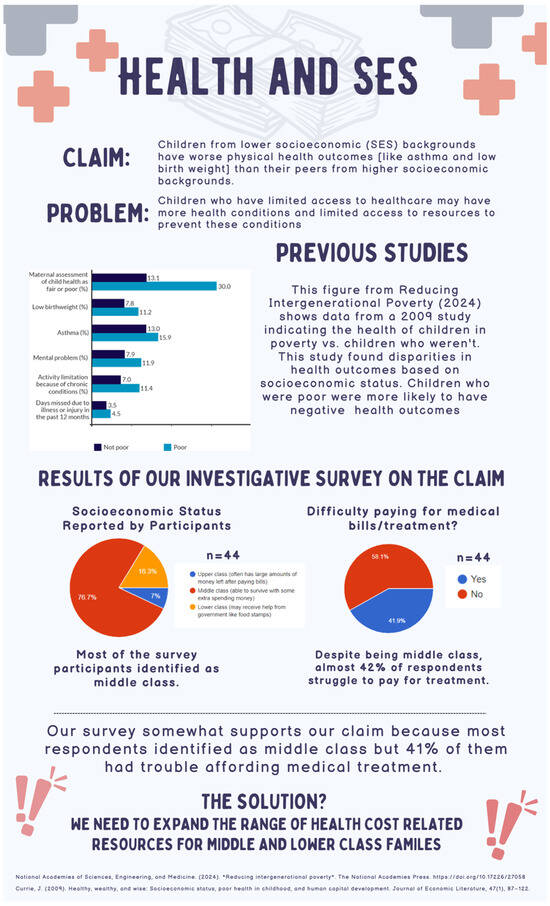

3.1. Economic Stability

Only two projects aligned with economic stability, including energy burden in low-income neighborhoods (P1) and health and socioeconomic status (P2). While these projects tended to be interdisciplinary in focus, assessing topics that aligned with the healthcare access and quality and neighborhood and built environment domains, they centered the impact of income-related disparities on individual outcomes. For instance, project one (P1) examined energy burden disparities between low-income and high-income neighborhoods, but did not propose a solution to this social problem. Project two (P2) explored disparities in children’s health-related incomes based upon socioeconomic status, where they found that healthcare costs had a negative impact on health outcomes for children from both middle and low SES backgrounds, suggesting the need of a community-level intervention to improve healthcare access. Overall, while economic stability included two interventions, elements of this SDOH factor can be seen across the domains, where income is frequently related to disparities in a variety of outcomes. A sample project that best illustrates this domain, P2, can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example of a student project in the economic stability domain (Project 2).

3.2. Education Access and Quality

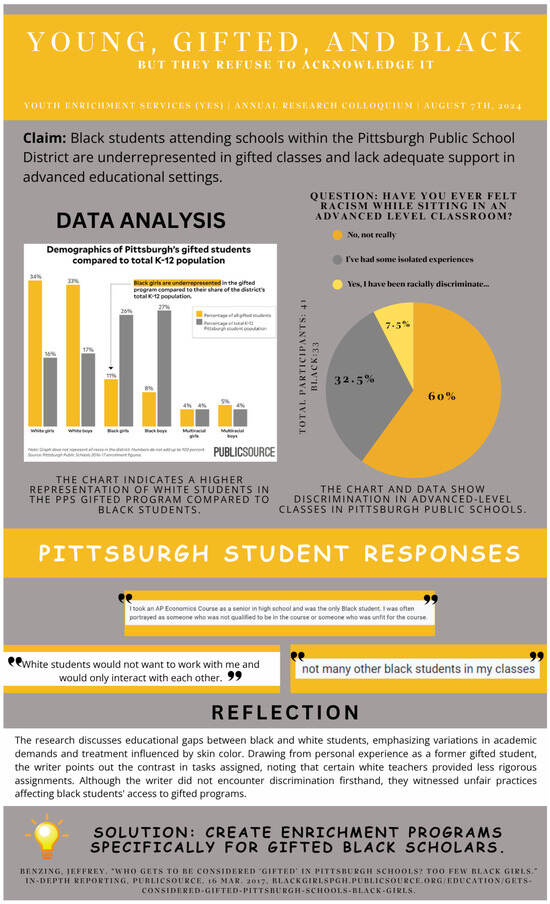

Projects that fit within the education access and quality domain (n = 5) examined the experiences of Black youth in public school and post-secondary education, including the following project topics: expanding Black history classes in public schools (P3, P4), young, gifted, and Black (P5), historically Black colleges and university (HBCU) funding (P6), and student debt injustice (P7). Students explored education access in public schools, where student projects investigated the importance of Black history classes and access to advanced education for gifted Black students. Education access was further explored in the post-secondary education context, where funding differences to HBCUs in comparison to predominantly white universities was identified as an important barrier to quality and equitable education. Students were also interested in the consequences of student debt for women and minority students, particularly as it relates to the wealth gap.

Out of the five projects within this domain, only three projects proposed a solution to address the student-identified social problem, including multilevel (n = 1), institutional (n = 1), and policy (n = 1). One student project approached expanding Black history classes through a multilevel solution. For example, project three (P3) proposed raising awareness to public school boards about the importance of Black history classes in an effort to expand Black history instruction, leveraging an interpersonal intervention to inspire institutional level change. Project five (P5) further proposed an institutional level change to public education, where enrichment programs that are inclusive to the needs of Black students could be leveraged to support education access. However, project six (P6) identified a policy level solution when addressing quality education access in the context of post-secondary education, where funding for HBCUs could be secured through a specialized government committee. Overall, student projects within this domain brought attention to barriers specific to marginalized populations, including minorities and women, and identified solutions that targeted institutions and policy to address education access and quality. A sample project that best illustrates this domain, P5, can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Example of a student project in the education access and quality domain (Project 5).

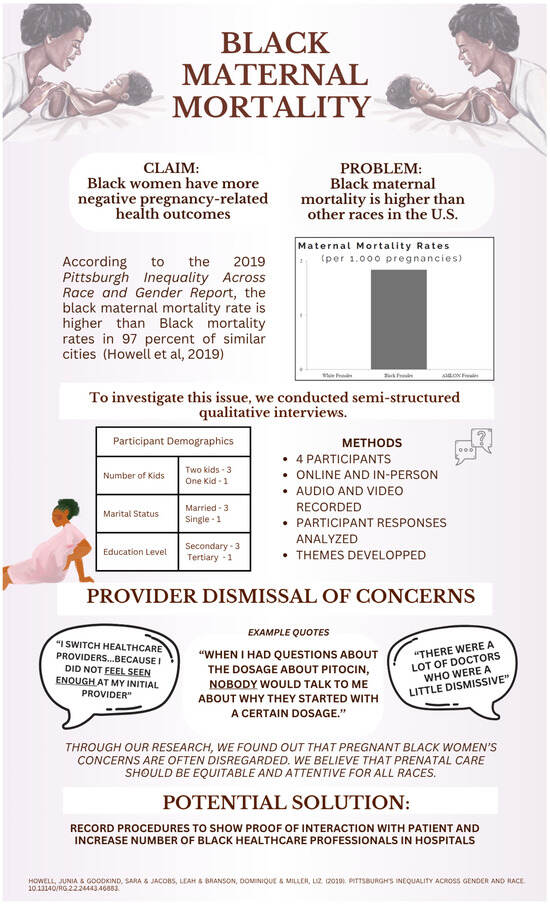

3.3. Healthcare Access and Quality

Healthcare access and quality encompassed projects (n = 4) that spanned issues relevant to today’s youth, including teen vaping (P9) and mental health literacy (P8), where students collected data about teens’ knowledge of mental health literacy and the health effects of vaping. Further, another student project applied their experiential knowledge of mental health solutions that are relevant to teens, where they explored the effects of listening to music on negative emotions (P11). Lastly, one student group conducted interviews to understand why and how Black women frequently receive negative pregnancy-related outcomes and healthcare quality, where they discovered most participants’ concerns were disregarded and not taken seriously by healthcare professionals (P10).

To address the social problems, students identified solutions that were related to healthcare access and quality. The majority of student groups selected institutional-level solutions (n = 2), suggesting students recognized the implications of structures and institutions on individual-level health outcomes. For example, two student groups reflected on the potential of schools to address students’ mental health, proposing school-provided music subscription platforms and curriculum to improve students’ mental health literacy. Another student group provided a tiered strategy that incorporated elements from both institutional and interpersonal-level interventions, where recording patient–provider interactions and increasing the number of Black healthcare professionals created a two-pronged approach to address pregnancy-related health outcome disparities for Black women. However, teen vaping was addressed through individual-level intervention, where students suggested that increasing awareness of the negative effects of vaping may serve as a deterrent against teen vape use. A sample project that best illustrates this domain, P10, can be found in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Example of a student project in the healthcare access and quality domain (Project 10).

3.4. Neighborhood and Built Environment

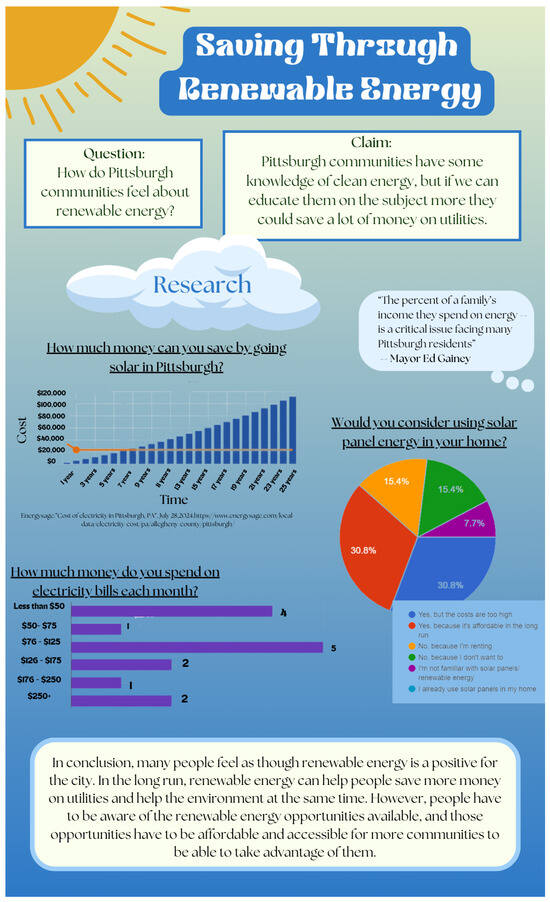

Projects that are best aligned with the neighborhood and built environment domain (n = 5) spanned a wide variety of project topics, including child nutrition (P12), environmental racism (P13), renewable energy (P14), power grid reliability and efficiency (P15), and access to outdoor green spaces (P16). Student projects frequently centered the experiences of marginalized communities and explored racial disparities relevant to [Redacted] communities, where students began to understand the connections between disproportionate outcomes and existing infrastructure in the community. For example, one group highlighted the connection between diet and access to healthy foods, where low-income communities typically have less affordable and fewer healthy food options. Furthermore, another group highlighted the importance of not only being able to access equitable community spaces and services but also ensure that those spaces are safe for community members.

Student-identified solutions to the social problem explored within each project encompassed multiple intervention levels, including institutional (n = 1), community (n = 1), policy (n = 1), and multilevel (n = 2), pointing to students’ recognition of the diverse and multilevel interventions needed to address SDOH factors. Students described solutions that highlighted the importance of adjusting existing systems, rather than targeting individual level factors, to address risk factors related to neighborhood and the built environment. For example, two groups proposed increasing awareness of environmental injustice and renewable energy options in an effort to, or in combination with, changing policy to best address community members’ needs. Overall, student projects within this domain brought attention to racial disparities within their community and emphasized the importance of solutions that target multiple intervention levels, particularly for complimenting interpersonal approaches to influence policy-related interventions. A sample project that best illustrates this domain, P14, can be found in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Example of a student project in the neighborhood and built environment domain (Project 14).

3.5. Social and Community Context

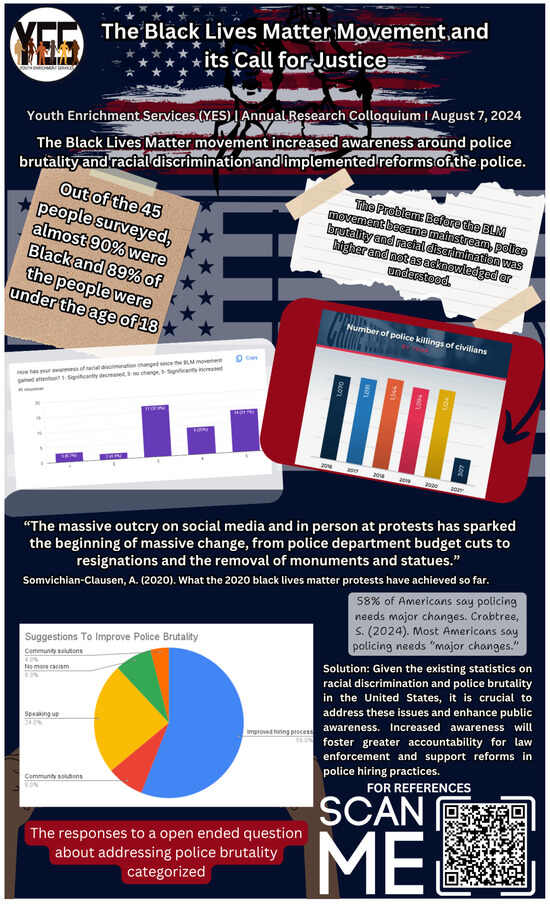

The majority of student projects covered social issues within the social and community context domain (n = 8), where topics examined various forms of violence, discrimination, and social movements. Five projects centered topics surrounding violence and crime, including violence and substance abuse (P17), pedophilia (P18), reproductive coercion (P19), human trafficking (P21), and LGBTQIA identities (P20). Students examined violence and its relationship with risk behaviors that impact health outcomes, where they situated violence as a particularly prevalent issue within low-income neighborhoods and in the context of social identities. For example, one group explored the relationship between substance abuse and violence, where they found that those who struggled with substance abuse tended to live in communities that experienced increased violence rates. Another group examined reproductive coercion in the context of domestic violence, where reproductive coercion was associated with negative effects to women’s physical and mental health. Students whose project centered LGBTQIA identities reflected on the connection between inadequate social media representation and frequency of hate crimes.

Two projects explored discrimination in different social contexts, including police brutality and discrimination (P22) and workplace discrimination (P24), and the associated negative impacts on health outcomes. For instance, one group explored pay differences due to discriminatory work practices, which have the potential to produce intergenerational poverty and negate one’s ability to accumulate wealth. Project twenty-two (P22) further explored discrimination, where they not only examined the negative effects of police brutality and discrimination for students within their community, but also explored practices that sustained harmful police practices over time, including a lack of accountability and consequences. Furthermore, students also explored the importance of social movements in addressing police brutality, where they examined the Black Lives Matter Movement (P23) and how it worked to address police brutality through police reforms and changes in hiring practices.

Students discussed a variety of approaches to address their social problem and promote social justice, including interpersonal (n = 1), institutional (n = 1), policy (n = 2), and multilevel (n = 1). One group suggested increasing awareness about reproductive coercion in an effort to prevent negative health outcomes for women. Furthermore, another group suggested increasing awareness about police brutality to create greater accountability for law enforcement, in an effort to create police reforms on an institutional level. Increasing the number of volunteers at anti-trafficking organizations was provided as an institutional solution to address human trafficking, suggesting community organizing may be beneficial to improve health outcomes. Some students identified policy-level solutions to address social issues, such as creating restrictions on children’s access to social media and implementing anti-discrimination laws in the workplace. A sample project that best illustrates this domain, P23, can be found in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Example of a student project in the social and community context domain (Project 23).

4. Discussion

This work extends the current literature on community-based organizations public health interventions by applying the SDOH framework to understand youth participatory action research projects. While much of the existing literature evaluates the effectiveness of large-scale public health interventions, few studies examine community-based organizational efforts to promote health equity. Furthermore, few studies apply the SDOH framework to understand how community-based organizations address health disparities, particularly through positioning youth as changemakers within this space. Exploring youth research projects provided a case study to understand the application of SDOH within the YPAR curriculum, social justice issues of interest to youth, and the types of interventions they tend to select to promote health equity. While research on youths’ YPAR engagement is robust (Anyon et al. 2018), scholarship on SDOH-grounded YPAR projects with youth is limited. As such, this work contributes to the YPAR literature and demonstrates how SDOH can support youth in developing thoughtful critiques of the root cause of social issues and innovative solutions.

Overall, the SDOH framework created flexibility within social justice coursework and supported students’ holistic understanding of the root cause of various social issues. Furthermore, the SDOH framework provided youth with a critical understanding of health disparities, providing youth with the knowledge and expertise necessary to be social justice advocates. However, the interdisciplinary nature of the five SDOH domains posited by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (n.d.) presented challenges when analyzing student projects, creating difficulties when aligning projects to domains, and teasing apart the nuance of each social issue and their meaning for health outcomes. While the SDOH domains provided a broad framework to inform social justice-related coursework and youth projects, a more comprehensive conceptual model is needed to improve its relevance to be used within practice-based settings and qualitative data analysis.

Youth selected a variety of topics for their projects, showcasing the depth and breadth of students’ interest in social issues. The majority of projects aligned with the social and community context, indicating youth may be most interested in addressing health disparities that impact social environments and relationships. Furthermore, students often chose projects that examined systemic inequities relevant to their lives, demonstrating youth interest in advancing social justice. Education access and quality and healthcare access and quality proved to be of interest to students, where students chose topics that were relevant to themselves and their community, including teen vaping, teen mental health, and accessing quality education in secondary school and colleges. These findings suggest that students may have more familiarity with and an in-depth understanding of issues that affect students their age, providing them with a critical perspective in generating creative solutions for this age group. Less common were student projects whose main focus was economic stability, indicating the need to further push students to tease apart the role economic status has in influencing health disparities. However, elements of economic stability appeared in other projects, where this domain may be more interdisciplinary than others.

Student-created solutions to social issues spanned a variety of intervention levels and types, with particular emphasis on institutional, policy, and multilevel solutions. These findings indicate students understood the root causes behind social issues to be the result of inequitable structures and systems that require interventions at multiple ecological levels to fully address the problem, reflecting the current literature that suggests multi-leveled interventions are critical in achieving health equity (Bigby 2011; Golden and Earp 2012). This further highlights the potential of social justice and SDOH framing to push students to think beyond individual and interpersonal level root causes. However, policy and institutional interventions are often challenging and difficult to navigate, which may require more scaffolding and include processes out of the scope of a short-term YPAR program. Instead, community-based organizations frequently aim to address social issues relevant to youth, providing a potential avenue for youth to plug into their communities, learn about best practices in addressing health equities, and actualize social justice initiatives on a local level. Pushing youth to develop solutions at the community-level may provide for more impact solutions and create opportunities for community engagement that extend beyond the end of YPAR programming.

Understanding how youth translate their knowledge building around inequitable systems and health disparities into tangible action and sustained advocacy are goals of future scholarship. Youth within this project gained positive benefits from engaging in health-related YPAR work. In fact, they learned how to facilitate justice-related community health conversations, as evidenced by their community stakeholder engagement at the final research colloquium (Youth Enrichment Services 2024). These individuals expressed growing commitment to making changes within their communities (Youth Enrichment Services 2024). Young people reported that, as their awareness of health inequities and possible interventions expanded throughout the program, they began to see themselves as helpful guides informing solutions to health disparities in their communities. Despite these positive program outcomes, less is known about how youths’ engagement in such YPAR programs influence long-term youth advocacy and community-level behavioral health changes. Existing research sheds some light on this and suggests youth residents have the capacity to ignite change within community contexts (Pinedo et al. 2024; Pinetta 2023); however, work in this area is still developing and outside of the scope of the reported study. Future scholarship will continue exploring how YPAR programs, like the one this study describes, influence youths’ roles as community change agents and disrupters of health inequities.

5. Conclusions

SDOH frameworks integrated within the YPAR curriculum have the potential to positively impact youth understanding of real-world social issues and develop tangible solutions to solve them. In order to best support youth in becoming changemakers for health equity, YPAR should center solutions at the community-level to improve intervention impact, develop youths’ professional networks, and incorporate assessment measures to understand how youths’ engagement in such programs facilitate changemaking behavior for youth and communities. Integrating youth into community-level solutions offers them a tangible and viable intervention point. Furthermore, community-level solutions create a stepping stone for youth to engage in social issues at the institutional or policy levels, where community-based grassroots efforts often garner increased attention over time. This work also provides practical implications for applying SDOH frameworks within YPAR programs. Future work should extend SDOH frameworks to support youth understanding of SDOH and their application in practice-based settings to tangibly impact health behaviors in communities. Additional work should also consider the intersectional nature of SDOH and how these overlapping nuances can exacerbate the health disparities of individuals living in marginalized and vulnerable communities and influence how youth make sense of SDOH within their neighborhoods as agents of change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L.J.; methodology, Z.V.P.; formal analysis, Z.V.P. and D.L.J.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.V.P.; writing—review and editing, D.C.E.S., D.L.J., L.D.C., K.S. and N.O.; project administration, D.L.J.; funding acquisition, D.F.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Partner4Work, grant number PY23P4WAMD3031.1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee—IRB Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences of University of Michigan (protocol code HUM00272809 and date of approval 30 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the course instructors for their support in curriculum development, delivery, and student project support. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of students as they developed projects and engaged in rigorous research coursework.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| YPAR | Youth participatory action research |

| SDOH | Social determinants of health |

| SEM | Socioecological model |

References

- Agnew, Christopher R., and Susan C. South. 2014. Interpersonal Relationships and Health: Social and Clinical Psychological Mechanisms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Eva H., Jennifer M. Haley, Joshua Aarons, and DaQuan Lawrence. 2021. Leveraging Community Expertise to Advance Health Equity. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association. 2022. A Strategy to Address Systemic Racism and Violence as Public Health Priorities: Training and Supporting Community Health Workers to Advance Equity and Violence Prevention (Policy Brief No. 20227). Available online: https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2023/01/18/address-systemic-racism-and-violence (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Anyon, Yolanda, Kimberly Bender, Heather Kennedy, and Jonah Dechants. 2018. A systematic review of youth participatory action research (YPAR) in the United States: Methodologies, youth outcomes, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior 45: 865–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baciu, Alina, Yamrot Negussie, Amy Geller, and James N. Weinstein, eds. 2017. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigby, JudyAnn. 2011. The role of communities in eliminating health disparities: Getting down to the grass roots. In Healthcare Disparities at the Crossroads with Healthcare Reform. Edited by R. Williams. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1977. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist 32: 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelak, Khushbu, and Swarupa Chakole. 2023. The Role of Social Determinants of Health in Promoting Health Equality: A Narrative Review. Cureus 15: e33425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, Shelley D., and Jo Anne L. Earp. 2012. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: Twenty years of health education and behavior health promotion interventions. Health Education & Behavior 39: 364–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, Derek M., Julie Ober Allen, E. Hill DeLoney, Kevin Robinson, E. Yvonne Lewis, Bettina Campbell, Susan Morrel-Samuels, Arlene Sparks, Marc A. Zimmerman, Thomas Reischl, and et al. 2010. Community-based organizational capacity building as a strategy to reduce racial health disparities. The Journal of Primary Prevention 31: 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haapanen, Krista A., Brian D. Christens, Paul W. Speer, and Hannah E. Freeman. 2024. Narrative change for health equity in grassroots community organizing: A study of initiatives in Michigan and Ohio. American Journal of Community Psychology 73: 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, Sarah. 2015. Axes of health inequalities and intersectionality. In Health Inequalities: Critical Perspectives. Edited by Katherine E. Smith, Clare Bambra and Sarah E. Hill. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, Carol, and Edward F. Lawlor. 2008. Community approaches to addressing health disparities. National Academy of Sciences. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215366/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Valuing Community-Based, Non-Clinical Prevention Policies, and Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice. 2012. An Integrated Framework for Assessing the Value of Community-Based Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, Elle, Nadia L. Dowshen, and Kellan E. Baker. 2020. Intersectionality and health inequities for gender minority Blacks in the US. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 59: 639–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malorni, Angie, Charles H. Lea, Katie Richards-Schuster, and Michael S. Spencer. 2022. Facilitating youth participatory action research (YPAR): A scoping review of relational practice in US Youth development and out-of-school time projects. Children and Youth Services Review 136: 106399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, Jme Suannah. 2019. Youth Civic Engagement for Health Equity and Community Safety: How Funders Can Embrace the Power of Young People to Advance Healthier, Safer Communities for All; Washington, DC: Philanthropy for Active Civic Engagement. Available online: https://www.pacefunders.org/youth-civic-engagement-for-health-equity-and-community-safety/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- McLeroy, Kenneth R., Daniel Bibeau, Allan Steckler, and Karen Glanz. 1988. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly 15: 351–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Robin L., and Marybeth Shinn. 2005. Learning from communities: Overcoming difficulties in dissemination from prevention and promotion efforts. American Journal of Community Psychology 35: 169–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncloa, Fe, and Chenira Smith. 2018. 4-H Social Justice Youth Development: A Guide for Youth Development Professionals; College Park: University of Maryland and University of California. Available online: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dd590a_72a1bbcd26ae4b44ba8a5877bb40370b.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, and Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States. 2017. The State of Health Disparities in the United States; Edited by James N. Weinstein, Amy Geller, Yamrot Negussie and Alina Baciu. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425844/ (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. n.d. Social Determinants of Health; Healthy People 2030. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Ozer, Emily J., Michelle Abraczinskas, Catherine Duarte, Ruchika Mathur, Parissa Jahromi Ballard, Lisa Gibbs, Elijah T. Olivas, Marlene Joannie Bewa, and Rima Afifi. 2020. Youth participatory approaches and health equity: Conceptualization and integrative review. American Journal of Community Psychology 66: 267–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinedo, Andres, Michael Frisby, Gabrielle Kubi, Victoria Vezaldenos, Matthew A. Diemer, Sara McAlister, and Elise Harris. 2024. Charting the longitudinal trajectories and interplay of critical consciousness among youth activists. Child Development 95: 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinetta, Bernardette. 2023. Pedagogy for Ethnic-Racial Identity Development: Reimaging Identities Rooted in Resistance (Publication No. 088535481). Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, Robert W, Pamela Paxton, Kristopher Velasco, Lilla Pivnick, Inbar Weiss, and Johannes C. Eichstaedt. 2021. Nonprofits: A public policy tool for the promotion of community subjective well-being. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 31: 822–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, James F., and Neville Owen. 2015. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5th ed. Edited by Karen Glanz, Barbara K. Rimer and Kasisomayajula Viswanath. Hoboken: Jossey-Bass/Wiley, pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, Daniel. 1996. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion 10: 282–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, Naima. 2024. Addressing health disparities through community-based public health initiatives. Health Science Journal 18: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, Amelia, Nancy De Lew, Andre Chappel, Victoria Aysola, Rachael Zuckerman, and Benjamin D. Sommers. 2022. Addressing Social Determinants of Health: Examples of Successful Evidence-Based Strategies and Current Federal Efforts; Report No. HP-2022-12. Washington, DC: Office of Health Policy. Available online: https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/sdoh-evidence-review (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, and World Health Organization. 2008. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Commission on Social Determinants of Health Final Report. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Youth Enrichment Services. 2024. Pathways to Success: 2024 Summer Report. Available online: https://www.youthenrichmentservices.org/_files/ugd/83a141_aa8140c4bebb4d4da825cb5654b94080.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).