Queer, Trans, and/or Nonbinary French as a Second Language (FSL) Teachers’ Embodiment of Inclusivity in Their Teaching Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do queer, trans, and/or nonbinary FSL teachers embody and enact a queer-inclusive learning space in their classrooms, if at all?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Inclusivity and Equity-Focused FSL Research

2.2. Cisheteronormativity Within L2 Research

3. Theoretical Framing

3.1. Queer Theory

3.1.1. Cisheteronormativity

3.1.2. Gender Performativity

3.1.3. Power

4. Methodology

Participants

5. Findings and Discussion

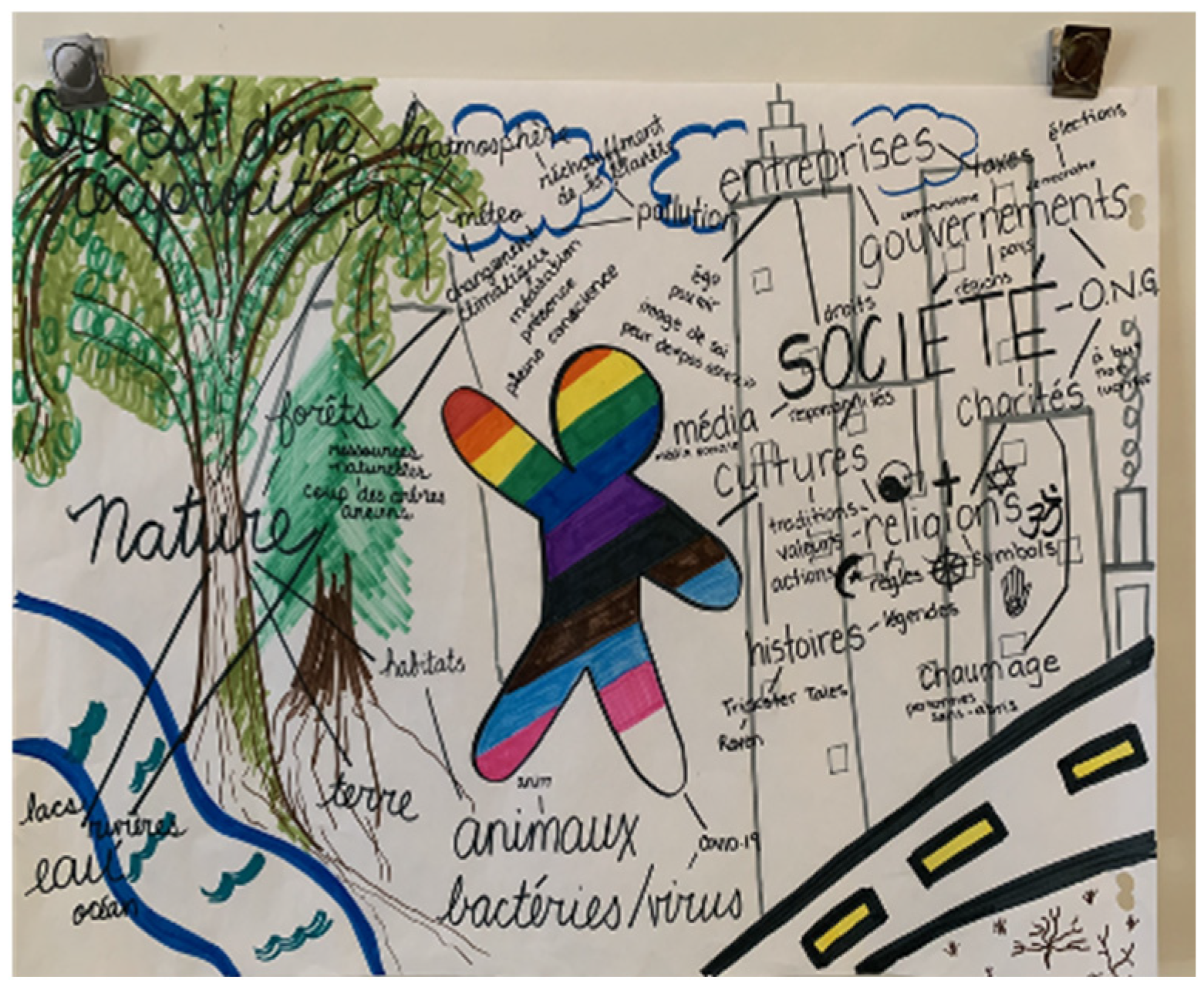

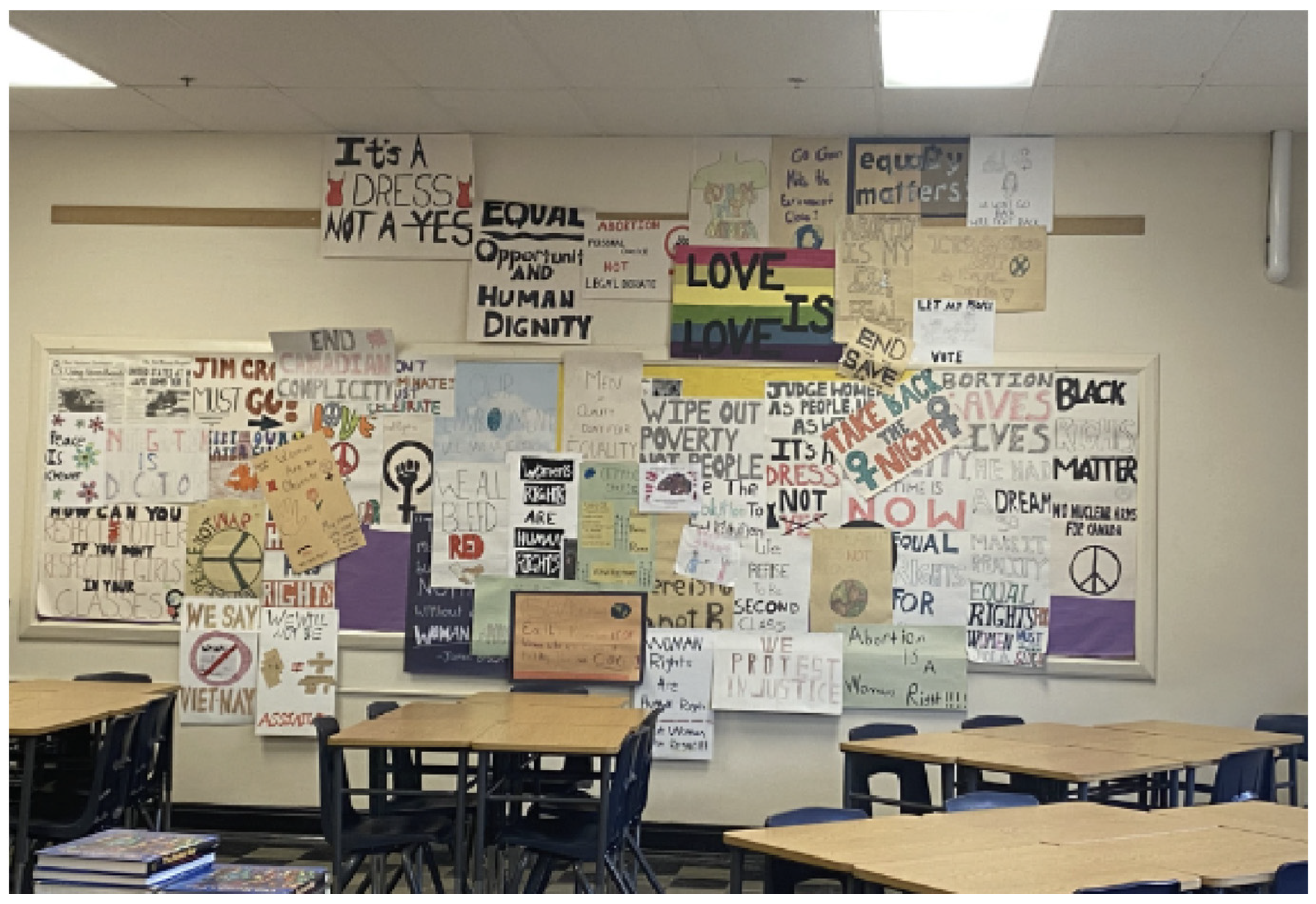

5.1. (In)visibility of Queerness

5.2. A Balancing Act

I think I eventually hid myself in my studies—I didn’t want to be known as gay so I needed to be highly performing at these other things. So I became very competitive, especially with the other academic girls, because I always did relate better to girls.

5.3. Urgency to Disrupt

Male student: You’re a boy teacher!Elm: Oh, no.Male student: Yes you are! You’re wearing a dinosaur shirt!Elm: Oh … let’s unpack this a little bit!

5.4. Navigating Teaching a Gendered Language

Jade’s practice of normalizing queer language in her French class acts as a catalyst for queer inclusion, which is important since other scholars have argued that such language tends to be absent generally in FSL spaces (Grant and Smith 2025; Hakeem 2024).And if we’re learning subject pronouns, like “je and tu,” and then I’ll also go “il, elle, iel,” just to normalize having it in the classroom. And I’ve had to have conversations with students for like, “what is this? Why is it here now? How are things changing in French?”

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adatia, Shelina. 2023. Un Examen Critique de L’inclusion en Immersion Française: A Multiple-Case Study at an Independent School in Ontario. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Katy. 2008. Exploring the use of student perspectives to inform topics in teacher education. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 11: 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Katy, and Callie Mady. 2010. A critically conscious examination of special education within FSL and its relevance to FSL teacher education programs. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 13: 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Arnott, Stephanie, Mimi Masson, and Sharon Lapkin. 2019. Exploring trends in 21st century Canadian K-12 French as second language research: A research synthesis. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 22: 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhuizen, Gary. 2022. Ten tricky questions about narrative inquiry in language teaching and learning research: And what answers mean for qualitative and quantitative research. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network 15: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Barkhuizen, Gary, Phil Benson, and Alice Chik. 2014. Narrative Inquiry in Language Teaching and Learning Research. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boland, Jared. 2021. In-Service Skill Development on Queer and Trans Identities and Literacy Practices for Ontario French as a Second Language Professionals. Master’s dissertation, The University of Toronto/OISE, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Annette. 2011. Walking yourself around as a teacher’: Gender and embodiment in student teachers’ working lives. British Journal of Sociology of Education 32: 275–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, Adam. 2024a. Under the spotlight: Exploring the challenges and opportunities of being a visible LGBT+ teacher. Sex Education 24: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, Adam. 2024b. Unveiling heteronormativity: A visual exploration of LGBT+ teachers’ experience using photo elicitation. Sex Education 25: 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cahnmann-Taylor, Melisa, James Coda, and Lei Jiang. 2022. Queer is as queer does: Queer L2 pedagogy in teacher education. TESOL Quarterly 56: 130–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, Vera, Pam Steeves, Jean Clandinin, Andrew Estefan, Janice Huber, and M. Shaun Murphy. 2018. Social justice practice: A narrative inquiry perspective. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 13: 133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, Tonya. 2018. Homophobia in the Hallways: Heterosexism and Transphobia in Canadian Catholic High Schools. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Christopher, Tracey Peter, and Catherine Taylor. 2021. Educators’ reasons for not practicing 2SLGBT+ inclusive education. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne de L’éducation 44: 964–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Shawna M., Daniela Bascuñán, Mark Sinke, and Jean Paul Restoule. 2020. How discomfort reproduces settler structures: “Moving beyond fear and becoming imperfect accomplices”. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching 9: 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Shawna M., Mimi Masson, Robert Grant, and Eric Keunne. 2025. It’s (in)escapable: Navigating a second language curriculum and its language in a settler colonial context. Modern Language Journal 109: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D. Jean. 2006. Narrative inquiry: A methodology for studying lived experience. Research Studies in Music Education 27: 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clandinin, D. Jean, and Michael Connelly. 2000. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Coda, James. 2018. Disrupting standard practice: Queering the world language classroom. SCOLT Dimension 74: 89. [Google Scholar]

- Coda, James. 2019. Do straight teachers experience this? Performance as a medium to explore LGBTQ world language teacher identity. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 32: 465–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, James, Kelly M. Moser, and Liv Halaas Detwiler. 2024. Queer theories and pedagogies in Spanish language education: Current status and future directions. Critical Multilingualism Studies 11: 103–29. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Adam W., and Ruth Neustifter. 2023. Heteroprofessionalism in the academy: The surveillance and regulation of queer faculty in higher education. Journal of Homosexuality 70: 1030–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Stephen, Susan Ballinger, and Mela Sarkar. 2019. The suitability of French immersion for allophone students in Saskatchewan: Exploring diverse perspectives on language learning and inclusion. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 22: 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, Hidehiro, Paul Chamness Reece-Miller, and Nicholas Santavicca. 2010. Surviving in the trenches: A narrative inquiry into queer teachers’ experience and identity. Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 1023–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferfolja, Tania, and Lucy Hopkins. 2013. The complexities of workplace experience for lesbian and gay teachers. Critical Studies in Education 54: 311–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, Michel. 1978. The History of Sexuality. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Robert. 2022. Eyes wide open: Navigating queer-inclusive teaching practices in the language classroom for pre-service teachers. In Every Teacher Is a Language Teacher: Social Justice and Equity Through Language Education. Edited by Mimi Masson, Heba Elsherief and Shelina Adatia. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Second Language Education Cohort (cL2c), pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Robert, and Cameron W. Smith. 2025. Voices of experience: Queer language teachers’ advice for new second language educators. Second Language Teacher Education Journal 4: 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Robert, and Elm Allister. n.d.Beyond the binary: Queer and trans activism in Ontario French as a second language (FSL) classroom. Journal of Queer and Trans Studies in Education. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Robert, Mimi Masson, and Shawna M. Carroll. 2024. Unraveling the silence around gender and sexuality in a second language curriculum. Journal of Language and Discrimination 8: 217–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, John. 2013. LGBT invisibility and heteronormativity in ELT materials. In Critical Perspectives on Language Teaching Materials. Edited by John Gray. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 40–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hakeem, Hasheem. 2022. Queering the French language classroom: A social justice approach to discussing gender, privilege, and oppression. In Diversity and Decolonization in French Studies: New Approaches to Teaching. Edited by Siham Bouamer and Loïc Bourdeau. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 183–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hakeem, Hasheem. 2023. Entre performance et fragilité: Mécanismes de construction de la masculinité chez des garçons du secondaire. McGill Journal of Education/Revue des Sciences de L’éducation de McGill 58: 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, Hasheem. 2024. Autocensure, délégitimation et dissonance émotionnelle chez des enseignant-e-s de français 2ELGBTQI+ au Canada. Arborescences 14: 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, Phillip, and Matthew Numer. 2017. The use of photo elicitation to explore the benefits of queer student advocacy groups in university. Journal of LGBT Youth 14: 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayatt, Didi, and Lee Iskander. 2019. Reflecting on ‘coming out’ in the classroom. Teaching Education 31: 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisely, Kris Aric. 2022. Gender-just language teaching and linguistic competence development. Foreign Language Annals 55: 644–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knisely, Kris Aric. 2023. Teaching Towards Gender Justice: Trans Knowledges in the Language Classroom. Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/600e13632c69ea16574db37d/t/6487c67620b1c1104413dec3/1686619771005/UCL_June+2023_Gender-just+language+pedagogies_Handout_Knisely.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Knisely, Kris Aric. 2024. Not another binary: Gender modality, languaging, and language learning in French. In Redoing Linguistic Worlds: Unmaking Gender Binaries, Remaking Gender Pluralities. Edited by Kris Aric Knisely and Evan L. Russell. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kunnas, Marika, Gail Prasad, Taylor Boreland, and Shayna Brissett-Foster. 2024. Building French-as-a-second-language teacher candidates’ linguistic confidence through drama-based activities. The Canadian Modern Language Review 80: 224–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnas, Marika, Mimi Masson, and Shawna M. Carroll. 2025. Conceptualizing culture critically: Examining perspectives from additional language teachers. Foreign Language Annals 58: 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnas, Marika R. 2023. Who is immersion for?: A critical analysis of French immersion policies. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 26: 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnas, Marika R. 2024. Monologues from the Margins: Voices and Experiences of Racially Minoritized French Immersion Students. Ph.D. dissertation, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Lander, Roderick. 2018. Queer English language teacher identity: A narrative exploration in Colombia. Profile Issues in Teachers Professional Development 20: 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapkin, Sharon, Callie Mady, and Stephanie Arnot. 2006. Preparing to profile the FSL teacher in Canada 2005–2006: A literature review. Modern Language Centre 25: 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lebrec, Caroline, Shreya Diwan, and Savindya Mudadeniya. 2024. «Students as Partners»: Une approche pédagogique innovante pour un curriculum queer. Arborescences 14: 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, Ruth. 2006. Limitations of language: Developing arts-based creative narrative in stories of teachers’ identities. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 12: 549–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddicoat, Anthony J. 2009. Sexual identity as linguistic failure: Trajectories of interactions in the heteronormative language classroom. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education 8: 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Hai, Wannapa Trakulkasemsuk, and Pattamawan Jimarkon Zilli. 2020. When queer meets teacher: A narrative inquiry of the lived experiences of a teacher of English as a foreign language. Sexuality and Culture 24: 1064–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Katrina. 2015. Critical reflection as a framework for transformative learning in teacher education. Educational Review 67: 135–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, Callie. 2020. Teacher adaptations to support students with special education needs in French immersion: An observational study. In Teacher Development for Immersion and Content-Based Instruction. Edited by Laurent Cammarata and Tadhg Joseph Ó Ceallaigh. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 93–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mady, Callie, and Katy Arnett. 2010. Inclusion in French immersion in Canada: One parent’s perspective. Exceptionality Education International 19: 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mady, Callie, and Katy Arnett. 2015. French as a second language teacher candidates’ conceptions of allophone students and students with learning difficulties. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 18: 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Martino, Alan Santinele, Eleni Moumos, Jordan Parks, Noah Ulicki, and Meghan Robbins. 2024. Growing up queer with a disability in Canada’s Bible belt. The International Journal of Disability and Social Justice 4: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, Mimi. 2018. Reframing FSL teacher learning: Small stories of (re) professionalization and identity formation. Journal of Belonging, Identity, Language, and Diversity 2: 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, Mimi. 2021. On working with racialized youth in French as a second language: One teacher’s culturally responsive practice. Revue Scientifique des Arts-Communication, Lettres, Sciences Humaines et Sociales 1: 16489. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, Mimi, Alaa Azan, and Amanda Battistuzzi. 2024. Centering social justice and well-being in FSL teacher identity formation to promote long-term retention. In Education 29: 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, Mimi, and Samantha Van Geel. 2023. A raciolinguistics exploration of pre-service ESL teachers’ conceptualization of plurilingualism using drawings. TESL Canada Journal 41: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, Mimi, and Simone Ellene Côté. 2024. Belonging and legitimacy for French language teachers: A visual analysis of raciolinguistic discourses. In Interrogating Race and Racism in Postsecondary Language Classrooms. Edited by Xiangying Huo and Clayton Smith. New York and London: IGI Global, pp. 116–49. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, Mimi, and Simone Ellene Côté. 2025. An arts-based multiliteracies approach to elicit meaning-making in language teacher identity work. In Arts-Based Multiliteracies for Teaching and Learning. New York and London: IGI Global, pp. 327–76. [Google Scholar]

- Masson, Mimi, Marika Kunnas, Taylor Boreland, and Gail Prasad. 2022. Developing an anti-biased, anti-racist stance in second language teacher education programs. Canadian Modern Language Review 78: 385–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, Jackso B., Jr. 2008. Gay teachers’ negotiated interactions with their students and (straight) colleagues. The High School Journal 92: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, Hannah, and Whitney Monaghan. 2020. Queer Theory Now: From Foundations to Futures. New York: Red Globe Press. [Google Scholar]

- McEntarfer, Heather Killelea, and Matthew D. Rice. 2022. Working within trans-affirmative, anti-trans, and cisnormative storylines: The experiences of transgender and non-binary teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education 135: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Elizabeth J. 2007. “But I’m not gay”: What straight teachers need to know about queer theory. In Queering Straight Teachers: Discourse in Identity and Education. Edited by Nelson M. Rodriguez and William Frederick Pinar. Lausanne: Peter Lang, pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, Tommaso M., and Holly R. Cashman. 2024. Why should we care about multilingualism, gender, and sexuality? International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 27: 631–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzi, Robert C. 2013. “There aren’t any gays here”: Encountering heteroprofessionalism in an international development workplace. Journal of Homosexuality 60: 1602–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizzi, Robert C. 2016. Heteroprofessionalism. In Queer Studies in Education. Edited by William Frederick Pinar, Nelson M. Rodriguez and Reta Ugena Whitlock. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 137–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mizzi, Robert C., and Jared Star. 2019. Queer eye on inclusion: Understanding lesbian and gay student and instructor experiences of continuing education. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education 67: 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moita-Lopes, Luiz Paulo. 2006. Queering literacy teaching: Analyzing gay-themed discourses in a fifth-grade class in Brazil. Journal of Language Identity and Education 5: 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Ashley R. 2016. Inclusion and exclusion: A case study of an English class for LGBT learners. TESOL Quarterly 50: 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Ashley R. 2019. Interpersonal factors affecting queer second or foreign language learners’ identity management in class. The Modern Language Journal 103: 428–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Ashley R. 2020. Queer inquiry: A loving critique. TESOL Quarterly 54: 1122–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Ashley R., James Coda, Julia Donnelly Spiegelman, and Melisa Cahnmann-Taylor. 2024. Queer breaches and normative devices: Language learners queering gender, sexuality, and the L2 classroom. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 27: 675–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Garold. 2009. Narrative inquiry. In Qualitative Research in Applied Linguistics: A Practical Introduction. Edited by Juanita Heigham and Robert A. Croker. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Cynthia D. 2006. Queer inquiry in language education. Journal of Language, Identity & Education 5: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Cynthia D. 2009. Sexual Identities in English Language Education: Classroom Conversations. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Cynthia D. 2016. The significance of sexual identity to language learning and teaching. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity. Edited by Siân Preece. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 351–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, Hanhthi, and Lajlim Yang. 2015. A queer learners identity positioning in second language classroom discourse. Classroom Discourses 6: 221–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 2013. The Ontario Curriculum: French as a Second Language Grades 4–8; Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Education.

- Ontario Ministry of Education. 2014. The Ontario Curriculum: French as a Second Language Grades 9–12; Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

- Paiz, Joshua M. 2015. Over the monochrome rainbow: Heteronormativity in ESL reading texts and textbooks. Journal of Language and Sexuality 4: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiz, Joshua M. 2017. Queering ESL teaching: Pedagogical and materials creation issues. TESOL Journal 9: 348–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiz, Joshua M. 2020. Queering the English Language Classroom: A Practical Guide for Teachers. Sheffield: Equinox Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pawelczyk, Joanna, Łukasz Pakuła, and Jane Sunderland. 2014. Issues of power in relation to gender and sexuality in the EFL classroom-An overview. Journal of Gender and Power 1: 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Polkinghorne, Donald E. 1995. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. Qualitative Studies in Education 8: 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, Christy M., and James Coda. 2017. It’s not in the curriculum: Adult English language teachers and LGBQ topics. Adult Learning 28: 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelman, Julia Donnelly. 2022. “You used ‘elle,’ so now you’re a girl”: Discursive possibilities for a non-binary teenager in French class. L2 Journal: An Open Access Refereed Journal for World Language Educators 14: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Nikki. 2003. A Critical Introduction to Queer Theory. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland, Jane. 2021. Foreign language textbooks and degrees of heteronormativity: Representation and consumption. In Linguistic Perspectives on Sexuality in Education: Representations, Constructions and Negotiations. Edited by Łukasz Pakuła. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tarrayo, Veronico N., and Rafaella R. Potestades. 2023. Understanding queer Filipino university teachers’ queering efforts in the English classroom. TESOL Quarterly 58: 830–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrayo, Veronico N., Jhonatan Vásquez-Guarnizo, and Mairon Felipe Tobar-Gómez. 2024. Exploring queer Colombian preservice English language teachers’ perceptions towards queering English language leaching. European Journal of Education 60: e12853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Catherine, Tracey Peter, Tanner L. McMinn, Tara Elliott, Stacey Beldom, Allison Ferry, Zoe Gross, Sarah Paquin, and Kevin Schachter. 2011. Every Class in Every School: The First National Climate Survey on Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia in Canadian Schools. Final Report. Toronto: Egale Canada Human Rights Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Thein, Amanda Haertling. 2013. Language arts teachers’ resistance to teaching LGBT literature and issues. Language Arts 90: 169–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulla, Mark B., and Joshua M. Paiz. 2023. Queer pedagogy in TESOL: Teachers’ perspectives and practices in Thai ELT classrooms. RELC Journal 56: 259–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unwin, Siobhan, River Starcevich, Svarah Lembo, and Madeleine Dobson. 2024. On becoming a queer educator: Reflections on queer perspectives and approaches in initial teacher education. Continuum 38: 307–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Gender | Sexuality | Pronouns | Number of Photos Shared |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angela | Female/gender queer | Bisexual/pansexual | she/her they/them | 3 |

| Caleb | Gender queer | Gay | he/they | 6 |

| Elm | Trans non/binary | Queer | they/them | 2 |

| Jade | Female | Asexual | she/her | 2 |

| Jason | Male | Gay | he/him | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grant, R. Queer, Trans, and/or Nonbinary French as a Second Language (FSL) Teachers’ Embodiment of Inclusivity in Their Teaching Practice. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100598

Grant R. Queer, Trans, and/or Nonbinary French as a Second Language (FSL) Teachers’ Embodiment of Inclusivity in Their Teaching Practice. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):598. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100598

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrant, Robert. 2025. "Queer, Trans, and/or Nonbinary French as a Second Language (FSL) Teachers’ Embodiment of Inclusivity in Their Teaching Practice" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100598

APA StyleGrant, R. (2025). Queer, Trans, and/or Nonbinary French as a Second Language (FSL) Teachers’ Embodiment of Inclusivity in Their Teaching Practice. Social Sciences, 14(10), 598. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100598