“The Medical System Is Not Built for Black [Women’s] Bodies”: Qualitative Insights from Young Black Women in the Greater Toronto Area on Their Sexual Health Care Needs

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Genealogies of Anti-Black Racism in Canada

1.2. Sexism and Gender-Based Discrimination in Canada

1.3. Intersectional Considerations for Black Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health in Canada

1.4. Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Provision in Canada

1.5. The Effects of COVID-19 on Virtual Care in Ontario

1.6. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Recruitment

2.2. Methodology

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Limitation

3. Results

3.1. Barriers to Care

3.1.1. Anti-Black (Sexual) Stigma

“Like sometimes the stigma of being called a slut or being hyper-sexualized, actually prevents you from taking steps to better your sexual health. Like there was one time when… like one of my friends, straight up got angry at me, hung up the phone on me, for taking plan B too many times. That’s not how it works. So, it’s just like all these stigmas… prevent you from actually taking care of yourself”.(FG1)

“And you look at the fact that there’s anti-Black racism, in accessing services, there’s the impact that anti-Black racism has on you, … we’re often asked to be stronger, and, and we’re forced to be resilient when it comes to facing certain barriers. And … some of that is a cultural stigma that keeps us from recognizing that, but then also, the medical system itself is not built in a way where it understands Black bodies”.(FG2)

3.1.2. Lack of Resources and Information

“As Black students, there’s often a lack of adequate services provided. And so if, for example, it’s unaffordable, to access those mental health services, or there’s no guidance counsellor at your school, who has any sort of, or who doesn’t have relevant lived experience, or who has inadequate training, then that makes it a lot more difficult”.(FG2)

“But even in university [it is] always about consent but never the steps or ways to stay safe while doing it. You see, it’s kind of funny because it’s like they want to promote safeness so they offer condoms, but they don’t explain other things that you need to do”.(FG2)

“I see white gatekeepers engaging with Black community members or Indigenous community members or other racialized folks. And, they expect this very sort of western frame of sexuality, that doesn’t include spirituality for example, and often in sexual health services you’ll find that’s completely devoid of any conversation”.(FG1)

3.1.3. Service Inaccessibility

“We need more than just sexual health clinics in the suburbs… like in rural areas and there might not necessarily be like large populations of LGBTQ+ Black youth that are in many of those spaces. Those are hugely underserved areas… And there needs to be more access to things like, … contraception, and kind of medication for STIs, for HIV, and for pregnancies”.(FG2)

“I think one big issue is that there aren’t free or low-cost options that are reasonable. Like I remember really sitting there, having a serious conversation with myself about whether birth control would show up as a name on my parent’s insurance documents, and whether it was worth going through that, or you know what, let me just work a few extra shifts, and handle that myself”.(FG1)

3.2. Healthcare Provider Competency

3.2.1. Misogynoir

“Black women are stigmatized to be viewed as women that are very sexually active, and I guess sexually expressive, and they’re comfortable with pregnancy. And, these types of STDs and STIs are common within our group. So, when you go to a doctor’s office, and you present to them certain symptoms that you may be facing, they’ll automatically right way assume are you pregnant, you have an STD because of their experiences, and the things that they see outside of the world with regards to Black women”.(FG2)

“I’ve read a couple of studies about how Black women are silenced. So, let’s say you’re in birth and you’re like I’m feeling this pain, they [health providers] kind of don’t really take your pain seriously. So, it’s like you can be addressing certain things or like voicing certain issues that you’re having but they’re just like pushing those things to the back burner, and those things can actually develop into something that’s actually serious. So, … a lot of Black women, they actually have like higher risk of dying during childbirth because they’re not actually listening to like ‘my back is hurting’ or like ‘I need this”.(FG1)

3.2.2. Eurocentric Health Practices

“I would say the lack of Black practitioners and or perhaps, practitioners that understand Black health… I do see it being a thing where, you know, you’re having practitioners who don’t necessarily have a cultural understanding. And are oftentimes, applying Eurocentric methodologies and Eurocentric ways of knowing as it relates to health care to the Black body in mind. And that in itself, can be devastating, or have devastating effects” (FG2). However, it is important to note that this perspective assumes empathy solely based on shared racial background, which may not be the case when additionally considering biases related to gender and sexuality that are ingrained within ACB cultures.

3.3. Virtual Care and Pandemic Adaptations

3.3.1. Benefits

“With online, in some ways, it’s actually a good thing as well, because I think here geographically things are so it’s very hard to access certain services, and commuting and things like that. So yeah, just kind of acknowledging that there is a need and getting more service providers to recognize that and then going from there in terms of providing more services here”.(FG1)

“Like I’m getting my information from an influencer, who is really outspoken about sexual health and everything, where to get smear tests, STIs, anything surrounding that information. So, this is a nice place to meet other women and just discuss how it affects me and get that knowledge that I did not get growing up”.(FG1)

3.3.2. Drawbacks

“A lot of youth that we work with, especially those who come from very underserved communities or who are not housed and they’re living in shelter spaces… Not sure if they actually have the resources they need to connect, or the space, the privacy, that kind of thing”.(FG1)

3.4. Intergenerational Beliefs About Sex, Sexuality, and Sexual Health

3.4.1. Fear of Sex/Uality

“And, so, we come to this space, we talk about the fear of sex in our cultures, and in our communities, and also the fear of you know queer members of our communities as well, and the stigma around that as a direct result of Christianity right. And, I think like really acknowledging for me anyways and always is to acknowledge that you know not too long ago, our cultures were not nested in rampant homophobia, and this fear of children, and the fear of sex, and viewing all of these things as a- these are very Christian ideals. These are not the origins of African cultures or diaspora cultures for that matter”.(FG1)

“I find that too, it comes from a place of fear, and like any way shape or form, like women, like Black women especially are sometimes hyper-sexualized. So, I think my mom specifically is very like cautious about like what are you wearing, what are you saying, who are you talking to, because people are not just going to paint you as a sexual person. They’ll paint you as a sexual Black woman, and that is somehow worse”.(FG1)

3.4.2. HIV/STI Stigma

“I’m Jamaican background, where you want to think about AIDS, I think about the homosexual community, and they were the only ones who could catch that the and you know, and bring it around out, you know, so I used to hear that growing up, so when I growing up, I used to assume that you like, like, as long as you’re not gay you’re not catching that. But you know, it turns out later on in my life that you know, that affects everyone, right?”.(FG2)

3.4.3. Intergenerational Influence on Sexual Education

“[M]y parents are of an African background too, and well, my dad no, but with my mom, it was always just don’t have sex. It was never, why, this is how, it was always just don’t do it, don’t get pregnant type of thing. I do remember one instance where she spoke to my brother and she was asking him if he knew about condoms and stuff and where to get it. So, I think a lot of it too is the double standards, where it’s okay for a boy child, a male, it’s okay as long as he is using condoms but like daughters cannot like you know. So, that’s kind of like, that was my experience growing up”.(FG1)

“And, there was one day, when I was like burning. I was like what’s going on? Turns out, it was just a yeast infection, everybody gets them, but I didn’t know that. So, I was walking around for literal weeks, just like in pain … There was one day when I just got tired, I was like Mom, listen, look, something is happening, I don’t know what it is, and she’s like well, what do you think it is?, … alluding to the fact that maybe it’s an STI … And, like even (if) it was, I shouldn’t be ashamed to talk, and to figure out if it is, and to get it treated but instead, I was just walking around for weeks in pain, over a simple yeast infection that you just go to the store and take a pill”.(FG1)

3.5. Centring ACB Youth

3.5.1. Building Community

“We created lots of different series, and workshops throughout the year that help to support with building that sense of community, supporting the capacity of young Black woman connecting them with their women their age, and just being able to reduce some of the isolation that often happens, both in a physical sense, and in a more personal sense, because as folks are navigating some really difficult and challenging times, … And so I know, it’s been really affirming for a lot of the young people to be able to connect with one another and see that I’m not alone in this struggle”.(FG2)

3.5.2. Increasing ACB Youth Leadership

“So what peer programs are really helpful, right, in terms of giving that, that freedom, that leeway, that leadership, that community capacity building, where we know that young people are experts, so let’s … let them have the conversation”.(FG1)

“Kind of co-developing curriculum to really offer what, what young people are asking for, and developing curriculum around their needs, and building trust and relationships that way and introducing, introducing other issues that they might not be speaking about, or asking for, but based on like, you know, the climate what’s happening in the neighbourhood”.(FG1)

3.6. Comfortable Space

3.6.1. Cultural Safety and Relevance

“Just as we Black women have you the facilitator, a Black person speaker, I’m pretty sure the LGBTQ+ [community] would also want someone they can relate to, sort of providing this information. It doesn’t come across the same way, when you have a heterosexual person standing here, telling you things that you feel are only specific to you”.(FG2)

“I think it has to be culturally relevant. Um, you know, simple things like the images. It seems simple, but it’s really not. The imaging that you use in your presentations, in your posts, the colours, you know? That makes a difference, because, at the end of the day, it has to be something that people want to come to”.(FG2)

“Like I haven’t seen my family doctor for over a decade, and then, I mentioned that I need to get my IUD replaced… with the ones that I used to see on campus, when I had my first IUD inserted, it was just like, it was the best pathway of care. They were so, they sat down with me and went through all the contraceptive methods… I went with an IUD in the end but they were just like so nice and approachable”.(FG1)

3.6.2. Holistic Care

“To me, it just means, you know, overall, physical, sexual, even mental well-being, and taking care of yourself and doing what you know, taking whatever steps you need to take to protect yourself and protect your loved ones. That includes, you know, education, that includes taking, like a harm reduction approach, whereas it relates to sexual engagement, whether you have one partner or several partners, and that also includes protecting yourself”.(FG2)

3.6.3. Anonymity and Confidentiality

“I hate having to enter the clinic, and then have to exit the same way. I feel like maybe they create something where like you come and then you could like exit through the back or something, where they have like another exit. So, like you know, you don’t have to worry about … who is going to see me coming out of this clinic”.(FG2)

“Maybe having systems put into place where people can anonymously question or ask things because not everyone in this day and age is comfortable walking into a place and asking a question… So, making things a little bit more privatized so that people… can access it in a private way that they feel they’re keeping their anonymity”.(FG2)

“What we do is … like anonymous surveys or questionnaires just to kind of, you know, hear from people, because some people might not be comfortable, you know, to speak up in a group about, you know, their experience, so we try to do anonymous surveys, just to kind of test the temperature of what people’s impression of the groups are, and, and how we can better support or improve the delivery of these programs”.(FG1)

4. Discussion

4.1. Religiosity, Colonialism, and the Policing of ACB Sexual Cultures

4.2. Resisting Institutionalized Anti-Blackness in Health and Social Service Sectors Through Community-Led Mechanisms

4.3. Affirming ACB Women’s Full Humanity Within Sexual Healthcare

4.4. ACB (Digital) Kinship as Sexual Health Promotion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SRH | Sexual Reproductive Health |

| ACB | African, Caribbean, and Black |

| GTA | Greater Toronto Area |

| HIP Teens | Health Improvement for Teens Intervention |

| OHIP | Ontario Health Insurance Plan |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

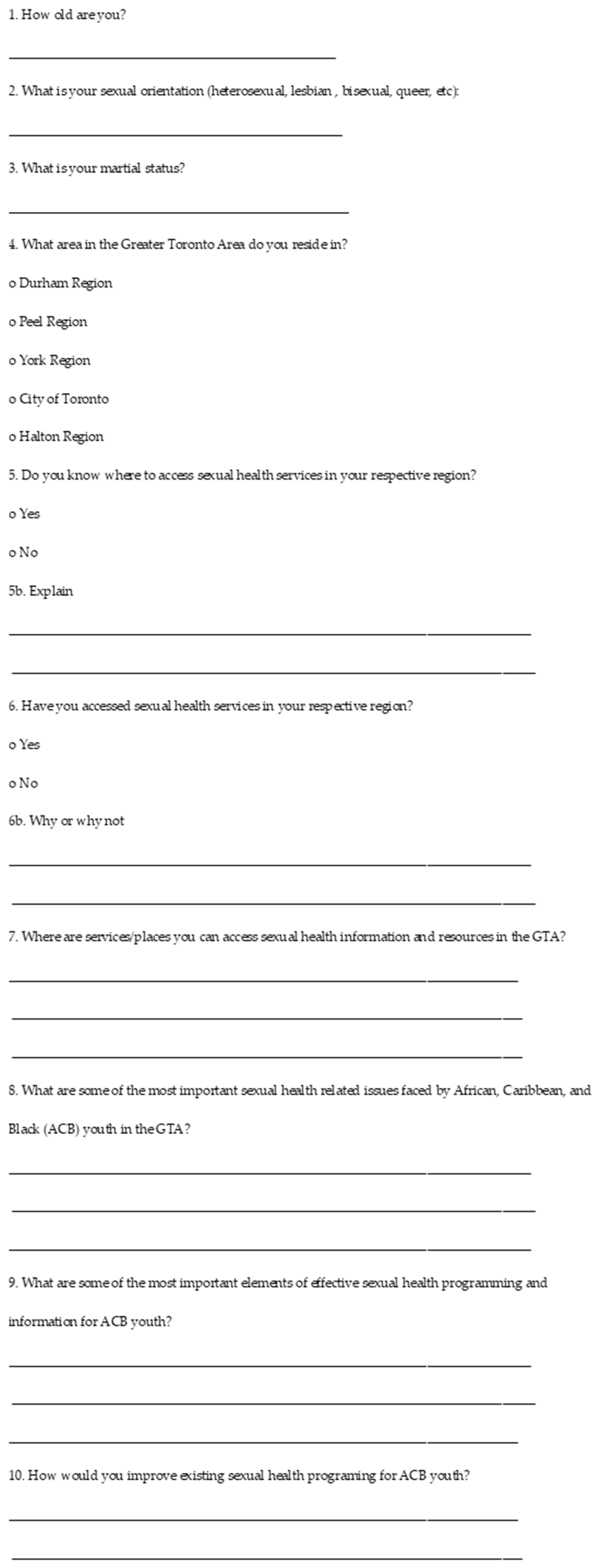

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Section/Question | Discussion Prompt | Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Preparation | Create comfortable environment. | |

| Introduction | Introduction of Research Coordinator | |

| Introduction | Welcome participants. | |

| Introduction | Overview of the topic. | |

| Introduction | Ground rules. | |

| Q1 | When I say the word sexual health, what comes to mind? What does sexual health mean to you? What does your sexual health include? | |

| Q2 | What are the most important sexual health issues facing young, Black women in the GTA? What are the pressing issues? | Probe: Can you explain why these issues might be occurring? What is at play? |

| Q3 | When you think about safe spaces, places and people to talk about sexual health—who/where/what is included in that list? | |

| Q4 | Where do you go to discuss your sexual health? | |

| Q5 | When you think about safe spaces, places and people to talk about sex? | Probe: School, friends, parents? |

| Q6 | What about STIs and HIV/AIDS? | |

| Q7 | What sexual health programming is available to you to discuss these issues of sex, sexual, STI’s etc.? | |

| Q8 | Where do you go for sexual health services? | Probe: Why do you go there? What prevents you from going to certain places? |

| Q9 | How would you improve the state of sexual health programs available to Black youth? What would you change/include etc.? What kind of sexual health programs or campaigns would be useful for Black youth like yourself? | |

| Q10 | About HIPTeens Intervention—describe HIPTeens and probe about what would be useful and NOT useful about such an intervention. What needs to change to improve it to make it relevant to Black youth? | |

| Q11 | How would you like to receive information on sexual health? | |

| Q12 | What is the best way to engage ACB youth and get them involved in sexual health issues? | |

| Q13 | Any final comments about sexual health and how it affects us as Black women? |

- Create comfortable environment.

- Introduction of Research Coordinator

- Welcome participants.

- Overview of the topic.

- Ground rules.

- When I say the word sexual health, what comes to mind? What does sexual health mean to you? What does your sexual health include?

- What are the most important sexual health issues facing young, Black women in the GTA? What are the pressing issues?

- Probe: Can you explain why these issues might be occurring? What is at play?

- 3.

- When you think about safe spaces, places and people to talk about sexual health—who/where/what is included in that list?

- 4.

- Where do you go to discuss your sexual health?

- 5.

- When you think about safe spaces, places and people to talk about sex?

- Probe: School, friends, parents?

- 6.

- What about STIs and HIV/AIDS?

- 7.

- What sexual health programming is available to you to discuss these issues of sex, sexual, STI’s etc.?

- 8.

- Where do you go for sexual health services ? Probe: Why do you go there? What prevents you from going to certain places?

- 9.

- How would you improve the state of sexual health programs available to Black youth? What would you change/include etc.? What kind of sexual health programs or campaigns would be useful for Black youth like yourself?

- 10.

- About HIPTeens Intervention—describe HIPTeens and probe about what would be useful and NOT useful about such an intervention. What needs to change to improve it to make it relevant to Black youth?

- 11.

- How would you like to receive information on sexual health?

- 12.

- What is the best way to engage ACB youth and get them involved in sexual health issues?

- 13.

- Any final comments about sexual health and how it affects us as Black women?

References

- Abdillahi, Idil. 2024. Algorithmic surveillance in the era of the mental health appsphere. American Journal of Community Psychology 73: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, Jacob Albin, Nikisha Shally Khare, and Azasma Tanvir. 2024. Variegated Racism: Exploring Experiences of Anti-Black Racism and Their Progression in Medical Education. Canadian Medical Association Journal 196: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhouse, Constance. 1994. Racial segregation in Canadian legal history: Viola Desmond’s challenge, Nova Scotia, 1946. Dalhousie LJ 17: 299–362. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/dalholwj17&i=364 (accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Barnes, Sandra. 2024. Christianity as a Spiritual Sidepiece: How Young Black People with Diverse Sexual Identities Navigate Religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 63: 445–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Kali, Yasin A. Khan, Stephen Mac, Raphael Ximenes, David M.J. Naimark, and Beate Sander. 2020. Estimation of COVID-19–induced depletion of hospital resources in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal 192: E640–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Joshua. 2019. Buck Theory. The Black Scholar 49: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R. Sacha, Cherry Chu, Andrea Pang, Mina Tadrous, Vess Stamenova, and Peter Cram. 2021. Virtual care use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A repeated cross-sectional study. Canadian Medical Association Journal Open 9: E107–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boakye, Priscilla N., Nadia Prendergast, Annette Bailey, McCleod Sharon, Bahareh Bandari, Awura-ama Odutayo, and Eugenia Anane Brown. 2024. Anti-Black Medical Gaslighting in Healthcare: Experiences of Black Women in Canada. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 57: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, Susan B., and Elizabeth A. Sheehy. 1986. Feminist perspectives on Law: Canadian theory and practice. Canadian Journal of Women and the Law 2: 1. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/cajwol2&i=19 (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, John, Patrice Reilly, Kerry Cuskelly, and Sarah Donnelly. 2020. Social Work, Mental Health, Older People and COVID-19. International Psychogeriatrics 32: 1205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Patricia H. 1990. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Boston: Unwin Hyman. [Google Scholar]

- Cram, Peter, Irfan Dhalla, and Janice Lup-Yee Kwan. 2016. Trade-Offs: Pros and Cons of Being a Doctor and Patient in Canada. Journal of General Internal Medicine 32: 563–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 2013. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In Feminist Legal Theories. Edited by Karen Maschke. London: Routledge, pp. 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Darko, Natasha. 2020. Exploring Young ACB Women’s Experiences of Navigating Sexual Exploring Young ACB Women’s Experiences of Navigating Sexual Health in the Greater Toronto Area. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University. [Google Scholar]

- DasGupta, Nan, Vinay Shandal, Daniel Shadd, and Andrew Segal. 2020. The Pervasive Reality of Anti-Black Racism in Canada. Boston: BCG Insights. Available online: https://web-assets.bcg.com/be/41/014a062448fbbc81c5037cc4f884/realities-of-anti-black-racism-in-canada-2020-12-12-updated.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- Douglas, John M., and Kevin A. Fenton. 2013. Understanding Sexual Health and Its Role in More Effective Prevention Programs. Public Health Reports 128: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterbrook, William T., and Hugh G.J. Aitken. 1988. Canadian Economic History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. 2023. Age of Consent to Sexual Activity. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/other-autre/clp/faq.html (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Government of Ontario. 2024. What OHIP Covers. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/what-ohip-covers (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2019. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. New York: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, Bell. 1984. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Brooklyn: South End Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ifekwunigwe, Jayne O. 2018. Entangled belongings: Reimagining transnational biographies of Black and global African diasporic kinship. In Contested Belonging: Spaces, Practices, Biographies. Edited by Halleh Ghorashi, Kathy Davis and Peer Smets. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- James, Carl, and Tana Turner. 2017. Towards Race Equity in Education: The Schooling of Black Students in the Greater Toronto Area. Toronto: York University, pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jean-Pierre, Johanne, and Carl E. James. 2020. Beyond pain and outrage: Understanding and addressing anti-Black racism in Canada. Canadian Review of Sociology 57: 708–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Allan G. 2005. The Gender Knot: Unraveling Our Patriarchal Legacy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kendi, Ibram X., and Keisha N. Blain. 2021. Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America 1619–2019. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Kia, Hannah, Margaret Robinson, Jenna MacKay, and Lori E. Ross. 2020. Poverty in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and two-spirit (LGBTQ2S+) populations in Canada: An intersectional review of the literature. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice 28: 21–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, June, Sarah Flicker, Susan Flynn, Crystal Layne, Adinne Schwartz, Robb Travers, Jason Pole, and Adrian Guta. 2017. The Ontario Sexual Health Education Update: Perspectives from the Toronto Teen Survey (TTS) Youth. Canadian Journal of Education 40: 1–24. Available online: https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/2264 (accessed on 5 October 2024).

- Lorde, Audre. 1984. Sister Outsider. Trumansburg: The Crossing Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lugones, Maria. 2007. Heterosexualism and the colonial/modern gender system. Hypatia 22: 186–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, Frank. 2010. Done with Slavery: The Black Fact in Montreal, 1760–1840. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press-MQUP, vol. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Cynthia, Modupe Tunde-Byass, and Karline Wilson-Mitchell. 2024. Achieving equity in reproductive care and birth outcomes for Black people in Canada. Canadian Medical Association Journal 196: E343–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, Robyn. 2017. Policing Black Lives: State Violence in Canada from Slavery to the Present. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mbuagbaw, Lawrence, Winston Husbands, Shamara Baidoobonso, Daeria Lawson, Muna Aden, Josephine Etowa, LaRon Nelson, and Wangari Tharao. 2022. A Cross-Sectional Investigation of HIV Prevalence and Risk Factors among African, Caribbean and Black People in Ontario: The A/C Study. Canada Communicable Disease Report 48: 429–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCammon, Holly J. 2003. “Out of the Parlors and into the Streets”: The Changing Tactical Repertoire of the US Women’s Suffrage Movements. Social Forces 81: 787–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKittrick, Katherine. 2015. Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mensah, Joseph, and Christopher J. Williams. 2022. Socio-structural injustice, racism, and the COVID-19 pandemic: A precarious entanglement among Black immigrants in Canada. Studies in Social Justice 16: 123–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molony, Barbara. 2017. Women’s Activism and “Second Wave” Feminism: Transnational Histories. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison-Beedy, Dianne, Sheryl H. Jones, Yinglin Xia, Xin Tu, Hugh F. Crean, and Michael P. Carey. 2013. Reducing sexual risk behavior in adolescent girls: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescent Health 52: 314–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison-Beedy, Dianne, Valérie Tóthová, and Martin Červený. 2024. What does a “theoretically-guided” intervention really look like? A guide for nursing and social science researchers. KONTAKT-Journal of Nursing & Social Sciences Related to Health & Illness 26: 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, Madison, Kerrie G. Wilkins-Yel, Anushka Sista, Aashika Anantharaman, and Natalie Seils. 2022. Decolonizing Purity Culture: Gendered Racism and White Idealization in Evangelical Christianity. Psychology of Women Quarterly 46: 316–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyar, Dhruv, Ciara Pendrith, Vanessa Kishimoto, Cherry Chu, Jamie Fujioka, Patricia Rios, R. Sacha Bhatia, Owen D. Lyons, Paula Harvey, Tara O’Brien, and et al. 2022. Quality of virtual care for ambulatory care sensitive conditions: Patient and provider experiences. International Journal of Medical Informatics 165: 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Jacke, and Tania Tribe. 2025. Coexistence and Colonialism: Religious Conversion and the Expansion of Christianity in Northeast Africa (Second–Sixteenth Centuries). Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Dorothy. 2014. Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, Sara. 2018. Intersectionality and its discontents: Intersectionality as traveling theory. European Journal of Women’s Studies 25: 403–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangster, Joan. 2018. One Hundred Years of Struggle: The History of Women and the Vote in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, James, LaPrincess C. Brewer, and Tiffany Veinot. 2021. Recommendations for Health Equity and Virtual Care Arising from the COVID-19 Pandemic: Narrative Review. JMIR Formative Research 5: e23233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorter-Bourhanou, and Jameliah Inga. 2024. The Combahee River Collective Statement and Black Feminist Universalism. Critical Philosophy of Race 12: 347–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siller, Heidi, and Nilüfer Aydin. 2022. Using an intersectional lens on vulnerability and resilience in minority and/or marginalized groups during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 894103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarusarira, Joram. 2020. Religion and Coloniality in Diplomacy. The Review of Faith & International Affairs 18: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Combahee River Collective. 2014. A Black Feminist Statement. Women’s Studies Quarterly 42: 271–80. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24365010 (accessed on 16 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Thorpe, Shemeka, Samuella Ware, Natalie Malone, Jardin Dogan-Dixon, and Candice N. Hargons. 2023. Listen to Black women: The power of Black women’s collective sexual wisdom about strategies to promote sexual pleasure and reduce sexual pain. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 21: 1391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toronto Teen Survey. 2010a. LGBTQ Bulletin. Toronto: Planned Parenthood Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Toronto Teen Survey. 2010b. What Did Black, African, and Caribbean Youth Have to Say? Toronto: Planned Parenthood Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Vass, Eliza, Zia Bhanji, Bisi Adewale, and Salima Meherali. 2022. Sexual and Reproductive Health Service Provision to Adolescents in Edmonton: A Qualitative Descriptive Study of Adolescents’ and Service Providers’ Experiences. Sexes 3: 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtual Care Task Force. 2022. Virtual Care in Canada: Progress and Potential. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association, pp. 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, Wendy. 2016. New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. New York: WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Winks, Robin W. 1997. Blacks in Canada: A History. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, vol. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Woodly, Deva, Rachel H. Brown, Mara Marin, Shatema Threadcraft, Christopher Paul Harris, Jasmine Syedullah, and Miriam Ticktin. 2021. The Politics of Care. Contemporary Political Theory 20: 890–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total Sample N = 24 n (%) | FG1 N = 13 n (%) | FG2 N = 11 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | 16–29 | 22–29 | 16–26 |

| Age mean and SD | M = 24.2 SD = 3.2 | M = 25.7 SD = 2.1 | M = 22.6 SD = 3.5 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African | 12 (50.0) | 7 (53.4) | 5 (45.4) |

| Caribbean | 8 (33.3) | 4 (30.8) | 4 (36.4) |

| Black-Canadian | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Mixed | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) |

| Other | 2 (8.3) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0) |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 24 (95.8) | ||

| Bisexual | 1 (4.2) | ||

| Region of Residence | |||

| City of Toronto | 11 (45.8) | 4 (30.8) | 7 (63.6) |

| Durham Region | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (27.3) |

| Peel Region | 4 (16.7) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (9.1) |

| York Region | 6 (25.0) | 6 (45.2) | 0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Randhawa, G.; Ramnarine, J.; Wilson, C.L.; Darko, N.; Abdillahi, I.; Cameron, P.; Morrison-Beedy, D.; Brisbane, M.; Alexander, N.; Kuye, V.; et al. “The Medical System Is Not Built for Black [Women’s] Bodies”: Qualitative Insights from Young Black Women in the Greater Toronto Area on Their Sexual Health Care Needs. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100581

Randhawa G, Ramnarine J, Wilson CL, Darko N, Abdillahi I, Cameron P, Morrison-Beedy D, Brisbane M, Alexander N, Kuye V, et al. “The Medical System Is Not Built for Black [Women’s] Bodies”: Qualitative Insights from Young Black Women in the Greater Toronto Area on Their Sexual Health Care Needs. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):581. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100581

Chicago/Turabian StyleRandhawa, Gurman, Jordan Ramnarine, Ciann L. Wilson, Natasha Darko, Idil Abdillahi, Pearline Cameron, Dianne Morrison-Beedy, Maria Brisbane, Nicole Alexander, Valerie Kuye, and et al. 2025. "“The Medical System Is Not Built for Black [Women’s] Bodies”: Qualitative Insights from Young Black Women in the Greater Toronto Area on Their Sexual Health Care Needs" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100581

APA StyleRandhawa, G., Ramnarine, J., Wilson, C. L., Darko, N., Abdillahi, I., Cameron, P., Morrison-Beedy, D., Brisbane, M., Alexander, N., Kuye, V., Clarke, W., Record, D., & Betts, A. (2025). “The Medical System Is Not Built for Black [Women’s] Bodies”: Qualitative Insights from Young Black Women in the Greater Toronto Area on Their Sexual Health Care Needs. Social Sciences, 14(10), 581. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100581