Mental Health of Refugees in Austria and Moderating Effects of Stressors and Resilience Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Measuring Mental Distress

3.2. Multivariate Estimation Approach

4. Empirical Results

Regression Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Categories/Values | Share (in Percent) |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | 15–24 years | 31.2 |

| 25–34 years | 41.0 | |

| 35–44 years | 18.9 | |

| 45–60 years | 8.9 | |

| Gender | Men | 83.5 |

| Women | 16.5 | |

| Country of origin | Afghanistan | 21.4 |

| Iraq | 15.1 | |

| Syria | 62.6 | |

| Iran | 0.9 | |

| Asylum application pending | Yes | 4.8 |

| No | 95.2 | |

| Years of arrival | Before 2013 | 9.6 |

| 2013 | 3.4 | |

| 2014 | 17.6 | |

| 2015 | 52.9 | |

| 2016–2018 | 16.5 | |

| Months since arrival in Austria | Mean (Std. dev.) | 40.9 (35.9) |

| Duration of migration in months | Mean (Std. dev.) | 6.8 (21.0) |

| Education | ISCED 0 | 7.4 |

| ISCED 1 | 13.4 | |

| ISCED 2 | 15.2 | |

| ISCED 3–4 | 31.4 | |

| ISCED 6–8 | 32.6 | |

| Language proficiency (Mean value of ‘understanding’ and ‘speaking well’ German on a Likert scale from 1 to 5) | Mean (Std. dev.) | 2.7 (0.7) |

| Working (current status) | Yes | 36.2 |

| No | 63.8 | |

| Living with a partner in same household | Yes | 28.7 |

| No | 71.3 | |

| Having a partner who is living in home country or other foreign country | Yes | 5.5 |

| No | 94.5 | |

| Living with children in same household | Yes | 34.5 |

| No | 65.5 | |

| Having children who are not living in the same household | Yes | 4.9 |

| No | 95.1 | |

| Living with further family members | Yes | 21.9 |

| No | 78.1 | |

| Housing satisfaction (measured on a Likert scale from 0 to 10) | Mean (Std. dev.) | 5.4 (3.3) |

| Experienced discrimination | Never | 31.2 |

| Rarely | 25.6 | |

| Sometimes | 28.4 | |

| Often | 7.4 | |

| Very often | 7.4 | |

| Having someone to talk to (about personal problems) | Yes | 64.4 |

| No | 35.6 | |

| Social network (number of people in Austria one feels close to except family members—cut-off point: 50) | Mean (Std. dev.) | 6.4 (9.0) |

| Physical pain | No pain | 48.5 |

| Very slight | 16.6 | |

| Slight | 12.7 | |

| Moderate | 15.1 | |

| Strong | 5.9 | |

| Very strong | 1.2 | |

| Kessler 10 score (10–50) | Mean (Std. dev.) | 20.4 (9.1) |

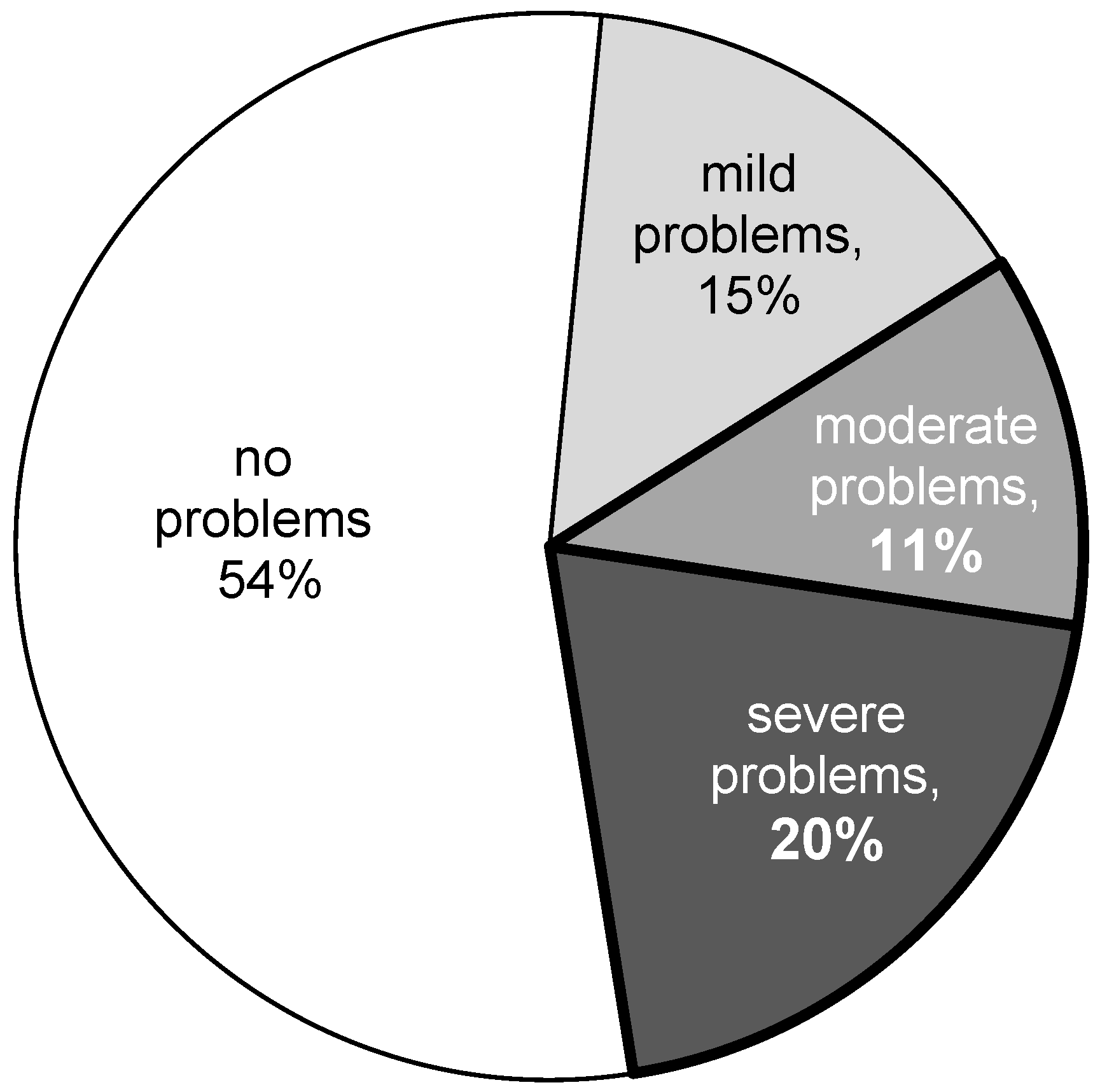

| Kessler 10 score groups | 10–19: Likely to be well | 54.0 |

| 20–24: Likely to have a mild disorder | 14.5 | |

| 25–29: Likely to have a moderate disorder | 11.3 | |

| 30–50 Likely to have a severe disorder | 20.2 | |

| Mode of interview | CAWI—invitation by e-mail | 64.1 |

| CAWI—Panel (invitation by e-mail) | 7.8 | |

| CASI/CAPI—at refugee facilities/centres | 21.5 | |

| CAWI—invitation by mail | 6.6 |

| Subgroups, % | K-10 Score, Mean Value | Moderate or Severe Mental Health Problems, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 20.4 | 31.4 | ||

| Gender | Men | 83.5 | 20.1 | 30.7 |

| Women | 16.5 | 22.2 | 35.1 | |

| Age group | 15–24 | 31.2 | 20.8 | 33.5 |

| 25–34 | 41.0 | 21.0 | 34.8 | |

| 35–44 | 18.9 | 18.7 | 22.0 | |

| 45–60 | 8.9 | 20.0 | 28.2 | |

| Country of origin | Afghanistan | 21.4 | 20.2 | 30.0 |

| Iraq | 15.1 | 21.7 | 38.3 | |

| Syria | 62.6 | 20.2 | 30.2 | |

| Iran | 0.9 | 18.7 | 28.6 | |

| Year of arrival | Before 2013 | 9.6 | 20.0 | 30.3 |

| 2013 | 3.4 | 20.3 | 25.9 | |

| 2014 | 17.6 | 20.2 | 30.0 | |

| 2015 | 52.9 | 20.7 | 33.8 | |

| 2016–2018 | 16.5 | 19.9 | 26.7 |

| 1 | In Appendix A, we present a summary table (Table A1) comprising all variables used for the sample remaining in the regression analysis. Moreover, a sensitivity analysis for this remaining sample concerning the descriptive results is presented in Table A2, showing no obvious bias. |

References

- Ager, Alastair, and Alison Strang. 2008. Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies 21: 166–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th (DSM-IV-TR)). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Aroian, Karen J., Anne E. Norris, Thanh V. Tran, and Nancy Schappler-Morris. 1998. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Demands of Immigration Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement 6: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMI. 2019. Asylstatistik 2018 [Asylum Statistics 2018]. Vienna: Austrian Federal Ministry of the Interior. [Google Scholar]

- BMI. 2025. Asylstatistik 2024 [Asylum Statistics 2024]. Vienna: Austrian Federal Ministry of the Interior. [Google Scholar]

- Bogic, Marija, Anthony Njoku, and Stefan Priebe. 2015. Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights 15: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, George A. 2004. Loss, Trauma, and Human Resilience: Have We Underestimated the Human Capacity to Thrive After Extremely Aversive Events? American Psychologist 59: 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehr, Kayvan, Amir Mohsenpour, Daniel Saure, Christian Stock, Adrian Loerbroks, Stefanie Joos, and Christine Schneider. 2016. Systematische Übersicht und „Mapping“ empirischer Studien des Gesundheitszustands und der medizinischen Versorgung von Flüchtlingen und Asylsuchenden in Deutschland (1990–2014). [Systematic review and mapping of empirical studies on the health status and medical care of refugees and asylum seekers in Germany (1990–2014)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt–Gesundheitsforschung–Gesundheitsschutz [Federal Health Gazette–Health Research–Health Protection] 59: 599–620. [Google Scholar]

- Brücker, Herbert, Nina Rother, and Jürgen Schupp. 2016. IAB-BAMF-SOEP-Befragung von Geflüchteten: Überblick und erste Ergebnisse. [IAB-BAMF-SOEP Survey of Refugees: Overview and Initial Findings]. Forschungsbericht [Research report] 29. Nürnberg [Nuremberg]: Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ) [Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), Research Centre for Migration, Integration and Asylum (FZ)]. [Google Scholar]

- Buchcik, Johanna, Viktoriia Kovach, and Adekunle Adedeji. 2023. Mental health outcomes and quality of life of Ukrainian refugees in Germany. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 21: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrà, Giuseppe, Paola Sciarini, Giovanni Segagni Lusignani, Massimo Clerici, Cristina Montomoli, and Ronald C. Kessler. 2011. Do they actually work across borders? Evaluation of two measures of psychological distress as screening instruments in a non Anglo-Saxon country. European Psychiatry 26: 122–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Wen, Brian J. Hall, Li Ling, and Andre M. N. Renzaho. 2017. Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: Findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. The Lancet. Psychiatry 4: 218–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, Paul. 2014. Exodus: Immigration and Multiculturalism in the 21st Century. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Velez, Ignacio, Sandra M. Gifford, and Adrian G. Barnett. 2010. Longing to belong: Social inclusion and wellbeing among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science & Medicine 71: 1399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Union. 2003. Council Directive 2003/9/EC of 27 January 2003 laying down minimum standards for the reception of asylum-seekers. Official Journal of the European Union 31: 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, Lee J. 1951. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16: 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, John, Liliya Gatina-Bhote, Pilar Rioseco, and Ben Edwards. 2017. Risk of Psychological Distress Among Recently Arrived Humanitarian Migrants. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Earnest, Jaya, Ruth Mansi, Sara Bayati, Joel Anthony Earnest, and Sandra C. Thompson. 2015. Resettlement experiences and resilience in refugee youth in Perth, Western Australia. BMC Research Notes 8: 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enticott, Joanne C., Frances Shawyer, Shiva Vasi, Kimberly Buck, I.-Hao Cheng, Grant Russell, Ritsuko Kakuma, Harry Minas, and Graham Meadows. 2017. A systematic review of studies with a representative sample of refugees and asylum seekers living in the community for participation in mental health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 17: 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. 2019. Your Key to European Statistics: Asylum and Managed Migration. Luxembourg: Eurostat. [Google Scholar]

- Fassaert, Thomas, Matty De Wit, Wilco Tuinebreijer, Hans Wouters, Arnoud Verhoeff, Aartjan T. F. Beekman, and Jack Dekker. 2009. Psychometric properties of an interviewer-administered version of the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) among Dutch, Moroccan and Turkish respondents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 18: 159–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, Mina, Jeremy Wheeler, and John Danesh. 2005. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. The Lancet 365: 1309–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Laura, Rahsan Yesil-Jürgens, Oliver Razum, Kayvan Bozorgmehr, Liane Schenk, Andreas Gilsdorf, Alexander Rommel, and Thomas Lampert. 2017. Gesundheit und gesundheitliche Versorgung von Asylsuchenden und Flüchtlingen in Deutschland. [Health and healthcare of asylum seekers and refugees in Germany]. Journal of Health Monitoring 2: 24–47. [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, Toshiaki A., Ronald C. Kessler, Toby Slade, and Gavin Andrews. 2003. The performance of the K6 and K10 screening scales for psychological distress in the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Psychological Medicine 33: 357–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, Robin E., Michael J. MacKenzie, Rawan W. Ibrahim, Kathryne B. Brewer, Jude S. Batayneh, and Craig S. J. Schwalbe. 2015. Stigma and mental health treatment of adolescents with depression in Jordan. Community Mental Health Journal 51: 111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, Ekaterini, Ali Zbidat, Gregor M. Schmitt, and Yesim Erim. 2018. Prevalence of mental distress among Syrian refugees with residence permission in Germany: A registry-based study. Frontiers in Psychiatry 9: 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacco, Domenico, and Stefan Priebe. 2018. Mental health care for adult refugees in high-income countries. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 27: 109–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesinger, Johannes, Gerhard Rumpold, and Gerhard Schüßler. 2008. Die K10-Screening-Skala für unspezifischen psychischen Distress. [The K10 screening scale for nonspecific psychological distress]. Psychosomatik und Konsiliarpsychiatrie [Psychosomatics and Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry] 2: 104–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajak, Vivien L., Srishti Sardana, Helen Verdeli, and Simone Grimm. 2021. A systematic review of factors affecting mental health and well-being of asylum seekers and refugees in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 643704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, Martina, Lutz Wittmann, Ulrike Ehlert, Ulrich Schnyder, Thomas Maier, and Julia Müller. 2014. Psychopathology and resident status—Comparing asylum seekers, refugees, illegal migrants, labor migrants, and residents. Comprehensive Psychiatry 55: 818–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic-Rankovic, Jelena, Rahul C. Oka, Jerrold S. Meyer, J. Josh Snodgrass, Geeta N. Eick, and Lee T. Gettler. 2022. Transient refugees’ social support, mental health, and physiological markers: Evidence from Serbian asylum centers. American Journal of Human Biology 34: e23747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkenaar, Marlies M. E., Manfred Maier, Ruth Kutalek, Antoine L. M. Lagro-Janssen, Robin Ristl, and Otto Pichlhöfer. 2013. Depression and anxiety among migrants in Austria: A population based study of prevalence and utilization of health care services. Journal of Affective Disorders 151: 220–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, Ronald C., Gavin Andrews, Lisa Colpe, Eva Hiripi, Daniel K. Mroczek, Sharon-Lise T. Normand, Ellen E. Walters, and Alan M. Zaslavsky. 2002. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine 32: 959–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, Christina, and Judith Kohlenberger. 2025. Navigating a paradox: Well-being and dimensions of (non-)belonging of Syrian refugees in Austria. Refugee Survey Quarterly 44: 318–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlenberger, Judith, Isabella Buber-Ennser, Bernhard Rengs, Sebastian Leitner, and Michael Landesmann. 2019. Barriers to health care access and service utilization of refugees in Austria: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health Policy 123: 833–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohrt, Brandon A., Andrew Rasmussen, Bonnie N. Kaiser, Emily E. Haroz, Sujen M. Maharjan, Byamah B. Mutamba, Joop T. V. M. de Jong, and Devon E. Hinton. 2014. Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: Literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology 43: 365–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laban, Cornelis J., Hajo B. P. E. Gernaat, Ivan H. Komproe, Ingeborg van der Tweel, and Joop T. V. M. De Jong. 2005. Postmigration living problems and common psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 193: 825–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiler, Anna, Anna Bjärtå, Johanna Ekdahl, and Elisabet Wasteson. 2019. Mental health and quality of life among asylum seekers and refugees living in refugee housing facilities in Sweden. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 54: 543–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedl, Alexandra, and Christine Knaevelsrud. 2008. Chronic pain and PTSD: The Perpetual Avoidance Model and its treatment implications. Torture: Quarterly Journal on Rehabilitation of Torture Victims and Prevention of Torture 18: 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lindert, Jutta, Ondine S. von Ehrenstein, Annette Wehrwein, Elmar Brähler, and Ingo Schäfer. 2018. Angst, Depressionen und posttraumatische Belastungsstörungen bei Flüchtlingen—Eine Bestandsaufnahme. [Anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder in refugees—A systematic review]. PPmP—Psychotherapie·Psychosomatik·Medizinische Psychologie [PPmP—Psychotherapy·Psychosomatics·Medical Psychology] 68: 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lolk, Mette, Stine Byberg, Jessica Carlsson, and Marie Norredam. 2016. Somatic comorbidity among migrants with posttraumatic stress disorder and depression—A prospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 16: 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löbel, Lea-Maria. 2020. Family separation and refugee mental health—A network perspective. Social Networks 61: 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbach, Moritz, Jens Hainmueller, and Dominik Hangartner. 2018. The long-term impact of employment bans on the economic integration of refugees. Science Advances 4: eaap9519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Kathryn. 2012. “The beat will make you be courage”: The role of a secondary school music program in supporting young refugees and newly arrived immigrants in Australia. Research Studies in Music Education 34: 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, AnnaMaria Aguirre, Lisa Stines Doane, Alice L. Costiuc, and Norah C. Feeny. 2009. Stress and Resilience. In Determinants of Minority Mental Health and Wellness. Edited by Sana Loue and Martha Sajatovic. New York: Springer, pp. 349–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadzadeh, Marjan, Hamidin Awang, and Frahnaz Mirzaei. 2020. Mental health stigma among Middle Eastern adolescents: A protocol for a systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 27: 829–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morina, Naser, Alexa Kuenburg, Ulrich Schnyder, Richard A Bryant, Angela Nickerson, and Matthis Schick. 2018. The Association of Post-traumatic and Postmigration Stress with Pain and Other Somatic Symptoms: An Explorative Analysis in Traumatized Refugees and Asylum Seekers. Pain Medicine 19: 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nationale Akademie der Wissenschaften Leopoldina [German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina]. 2018. Traumatisierte Flüchtlinge—Schnelle Hilfe ist jetzt nötig [Traumatised Refugees—Immediate Assistance Is Necessary Now]. Halle (Saale): German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. [Google Scholar]

- Nesterko, Yuriy, David Jaeckle, Michael Friedrich, L. Holzapfel, and Heide Glaesmer. 2020. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and somatisation in recently arrived refugees in Germany: An epidemiological study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 29: e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, Danielle N., Bethany Hedt-Gauthier, Shirley Liao, Nathaniel A. Raymond, and Till Bärnighausen. 2018. Major depressive disorder prevalence and risk factors among Syrian asylum seekers in Greece. BMC Public Health 18: 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, Matthew, and Nick Haslam. 2005. Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA 294: 602–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priebe, Stefan, Domenico Giacco, and Rawda El-Nagib. 2016. Public Health Aspects of Mental Health Among Migrants and Refugees: A Review of the Evidence on Mental Health Care for Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Irregular Migrants in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Renner, Anna, Rahel Hoffmann, Michaela Nagl, Susanne Roehr, Franziska Jung, Thomas Grochtdreis, Hans-Helmut König, Steffi Riedel-Heller, and Anette Kersting. 2020. Syrian refugees in Germany: Perspectives on mental health and coping strategies. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 129: 109906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, Hugues, Mark A. Zamorski, and Ian Colman. 2018. The psychometric properties of the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) in Canadian military personnel. PLoS ONE 13: e0196562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, Chesmal, Shirwa Sheik Ali, Bayard Roberts, and Robert Stewart. 2014. A systematic review of resilience and mental health outcomes of conflict-driven adult forced migrants. Conflict and Health 8: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strømme, Elisabeth M., Jasmin Haj-Younes, Wegdan Hasha, Lars T. Fadnes, Banti Kumar, Jannicke Igland, and Esperanza Díaz. 2020. Changes in health among Syrian refugees along their migration trajectories from Lebanon to Norway: A prospective cohort study. Public Health 186: 240–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman-Hill, Cheryl, and Sandra C. Thompson. 2010. Selecting instruments for assessing psychological wellbeing in Afghan and Kurdish refugee groups. BMC Research Notes 3: 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Expert Council for Integration. 2018. Integration Report 2018. Vienna: Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs (BMEIA). [Google Scholar]

- Thelin, Camilla, Benjamin Mikkelsen, Gunnar Laier, Louise Turgut, Bente Henriksen, Lis Raabaek Olsen, Jens Knud Larsen, and Sidse Arnfred. 2017. Danish translation and validation of Kessler’s 10-item psychological distress scale—K10. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 71: 411–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turrini, Giulia, Marianna Purgato, Francesca Ballette, Michela Nosè, Giovanni Ostuzzi, and Corrado Barbui. 2017. Common mental disorders in asylum seekers and refugees: Umbrella review of prevalence and intervention studies. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 11: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, Enrico, Stefan R. Bornstein, Rotem Shlomo Lanzman, Clemens Kirschbaum, Susan Sierau, Mirko Doehnert, Peter Zimmermann, Heinz Kindler, Maggie Schauer, Martina Ruf-Leuschner, and et al. 2018. Countering posttraumatic LHPA activation in refugee mothers and their infants. Molecular Psychiatry 23: 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ee, Elisa, Rolf J. Kleber, Marian J. Jongmans, Trudy T. M. Mooren, and Dorothee Out. 2016. Parental PTSD, adverse parenting and child attachment in a refugee sample. Attachment & Human Development 18: 273–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigl, Marion, and Sylvia Gaiswinkler. 2019. Blickwechsel—Migration und psychische Gesundheit [Change of Perspective—Migration and Psychological Health]. Vienna: Gesundheit Österreich [Austrian National Public Health Institute]. [Google Scholar]

- Yehuda, Rachel. 2004. Risk and resilience in posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65 Suppl. S1: 29–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zajacova, Anna, and Elizabeth M. Lawrence. 2018. The Relationship Between Education and Health: Reducing Disparities Through a Contextual Approach. Annual Review of Public Health 39: 273–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subgroups, % | K-10 Score, Mean Value | Moderate or Severe Mental Health Problems, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 20.9 | 31.6 | ||

| Gender | Men | 79.0 | 20.5 | 30.7 |

| Women | 21.0 | 22.3 | 35.1 | |

| Age group | 15–24 | 33.1 | 21.5 | 34.9 |

| 25–34 | 39.8 | 20.7 | 32.5 | |

| 35–44 | 18.7 | 19.5 | 24.3 | |

| 45–60 | 8.4 | 20.8 | 27.7 | |

| Country of origin | Afghanistan | 27.1 | 20.5 | 28.1 |

| Iraq | 13.7 | 22.6 | 40.7 | |

| Syria | 57.8 | 20.5 | 31.0 | |

| Iran | 1.5 | 23.5 | 40.9 | |

| Year of arrival | Before 2013 | 13.4 | 20.7 | 30.6 |

| 2013 | 4.2 | 20.9 | 32.3 | |

| 2014 | 16.2 | 20.1 | 28.0 | |

| 2015 | 48.7 | 21.0 | 33.0 | |

| 2016–2018 | 17.5 | 21.1 | 31.4 |

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Models | OLS | Logit | OLS | Logit |

| Dependent Variable | Kessler 10 Score | Medium or Severe Mental Health State | Kessler 10 Score | Medium or Severe Mental Health State |

| (10–50) | (10–50) | |||

| Years of Arrival | All | All | 2014–2018 | 2014–2018 |

| Age groups (reference group: 35–44) | ||||

| 15–24 years | 3.426 *** | 1.049 *** | 3.808 *** | 1.103 *** |

| (1.115) | (0.334) | (1.211) | (0.362) | |

| 25–34 years | 2.377 *** | 0.804 *** | 2.287 *** | 0.759 ** |

| (0.825) | (0.278) | (0.884) | (0.298) | |

| 45–60 years | 0.843 | 0.186 | 0.906 | 0.030 |

| (1.081) | (0.378) | (1.204) | (0.443) | |

| Women | 1.446 * | 0.223 | 1.154 | 0.287 |

| (0.850) | (0.241) | (0.945) | (0.278) | |

| Physical pain (reference group: no pain) | ||||

| Very slight | 2.768 *** | 0.594 ** | 2.719 *** | 0.596 ** |

| (0.827) | (0.252) | (0.895) | (0.280) | |

| Slight | 3.017 *** | 0.813 *** | 3.002 *** | 0.850 *** |

| (0.910) | (0.267) | (0.985) | (0.286) | |

| Moderate | 4.930 *** | 1.167 *** | 5.410 *** | 1.312 *** |

| (0.897) | (0.248) | (0.942) | (0.266) | |

| Strong | 5.899 *** | 1.028 ** | 5.940 *** | 0.982 ** |

| (1.544) | (0.399) | (1.719) | (0.421) | |

| Very strong | −1.321 | −0.100 | −5.051 | −1.225 |

| (3.485) | (0.891) | (3.582) | (1.367) | |

| Duration of migration in months | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.009 | −0.000 |

| (0.011) | (0.004) | (0.015) | (0.005) | |

| Months since arrival in Austria | 0.012 | 0.004 * | 0.014 | 0.011 |

| (0.008) | (0.002) | (0.038) | (0.012) | |

| Asylum application pending | 6.226 *** | 1.664 *** | 6.522 *** | 1.927 *** |

| (1.705) | (0.480) | (1.753) | (0.520) | |

| Living with a partner in same household | 0.598 | 0.220 | 0.441 | 0.275 |

| (0.801) | (0.251) | (0.856) | (0.275) | |

| Having a partner who is living in | 3.234 ** | 1.014 ** | 1.051 | 0.355 |

| home country or other foreign country | (1.577) | (0.421) | (1.600) | (0.515) |

| Living with children in same household | −0.791 | −0.240 | −0.860 | −0.347 |

| (0.921) | (0.270) | (0.990) | (0.297) | |

| Having children who are not living | 3.284 ** | 1.085 ** | 3.758 ** | 1.420 *** |

| in the same household | (1.616) | (0.468) | (1.733) | (0.525) |

| Living with further family members | −1.324 * | −0.297 | −1.834 ** | −0.452 * |

| (0.774) | (0.242) | (0.808) | (0.263) | |

| Someone to talk to | −1.198 * | −0.140 | −1.168 * | −0.162 |

| (0.648) | (0.198) | (0.695) | (0.217) | |

| Social network | −0.362 *** | −0.094 *** | −0.349 *** | −0.081 ** |

| (0.085) | (0.029) | (0.088) | (0.032) | |

| Social network2 | 0.007 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.007 *** | 0.001 ** |

| (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| Education (reference group: ISCED 0) | ||||

| ISCED 1 | 3.363 *** | 1.272 *** | 2.990 ** | 1.188 ** |

| (1.298) | (0.473) | (1.422) | (0.603) | |

| ISCED 2 | 3.916 *** | 1.361 *** | 3.152 ** | 1.195 * |

| (1.404) | (0.494) | (1.537) | (0.622) | |

| ISCED 3–4 | 3.126 ** | 1.275 *** | 3.300 ** | 1.357 ** |

| (1.255) | (0.466) | (1.373) | (0.587) | |

| ISCED 6–8 | 3.878 *** | 1.312 *** | 4.166 *** | 1.434 ** |

| (1.341) | (0.483) | (1.461) | (0.605) | |

| Working | −2.004 *** | −0.397 * | −1.843 ** | −0.325 |

| (0.654) | (0.203) | (0.717) | (0.224) | |

| Language proficiency | −1.075 ** | −0.325 ** | −0.930 * | −0.338 * |

| (0.499) | (0.161) | (0.545) | (0.176) | |

| Experienced discrimination | 1.427 *** | 0.345 *** | 1.552 *** | 0.370 *** |

| (0.280) | (0.079) | (0.302) | (0.088) | |

| Housing satisfaction | −0.240 *** | −0.061 ** | −0.204 ** | −0.063 ** |

| (0.091) | (0.028) | (0.098) | (0.032) | |

| Country of origin (reference group: Afghanistan) | ||||

| Iraq | 1.646 | 0.553 | 1.902 | 0.687 |

| (1.280) | (0.365) | (1.372) | (0.419) | |

| Syria | 1.318 | 0.386 | 1.274 | 0.515 |

| (0.983) | (0.307) | (1.022) | (0.348) | |

| Iran | −0.195 | 0.088 | 1.053 | 0.521 |

| (3.023) | (1.028) | (3.523) | (1.222) | |

| Mode of interview (reference group: CAWI—by e-mail) | ||||

| CAWI—Panel | −2.530 *** | −0.852 ** | −2.346 ** | −0.732 ** |

| (0.928) | (0.353) | (1.038) | (0.373) | |

| CASI/CAPI—at refugee facilities/centres | −2.015 ** | −0.330 | −2.082 ** | −0.341 |

| (0.879) | (0.293) | (0.897) | (0.313) | |

| CAWI—invitation by mail | 0.504 | −0.088 | 0.644 | −0.091 |

| (1.361) | (0.348) | (1.406) | (0.368) | |

| Constant | 9.585 *** | −4.523 *** | 9.751 *** | −4.948 *** |

| (2.472) | (0.824) | (3.179) | (1.108) | |

| Observations | 794 | 792 | 691 | 687 |

| R-squared | 0.272 | 0.173 | 0.294 | 0.186 |

| Province fixed effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leitner, S.; Landesmann, M.; Kohlenberger, J.; Buber-Ennser, I.; Rengs, B. Mental Health of Refugees in Austria and Moderating Effects of Stressors and Resilience Factors. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100570

Leitner S, Landesmann M, Kohlenberger J, Buber-Ennser I, Rengs B. Mental Health of Refugees in Austria and Moderating Effects of Stressors and Resilience Factors. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):570. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100570

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeitner, Sebastian, Michael Landesmann, Judith Kohlenberger, Isabella Buber-Ennser, and Bernhard Rengs. 2025. "Mental Health of Refugees in Austria and Moderating Effects of Stressors and Resilience Factors" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100570

APA StyleLeitner, S., Landesmann, M., Kohlenberger, J., Buber-Ennser, I., & Rengs, B. (2025). Mental Health of Refugees in Austria and Moderating Effects of Stressors and Resilience Factors. Social Sciences, 14(10), 570. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100570