Welfare Conditionality and Social Identity Effect Mechanisms and the Case of Immigrant Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Social Identity and Self-Determination Theory

2.1. (Social) Identity Theory

2.1.1. Individual Identity

2.1.2. Basic Ideas of Social Identity Theory

2.1.3. Summing Up

2.2. Self-Determination Theory

2.2.1. Basic Ideas of Self-Determination Theory

2.2.2. Autonomy and Extrinsic Motivation

2.2.3. Summing Up

3. Welfare Conditionality and Social Motivations

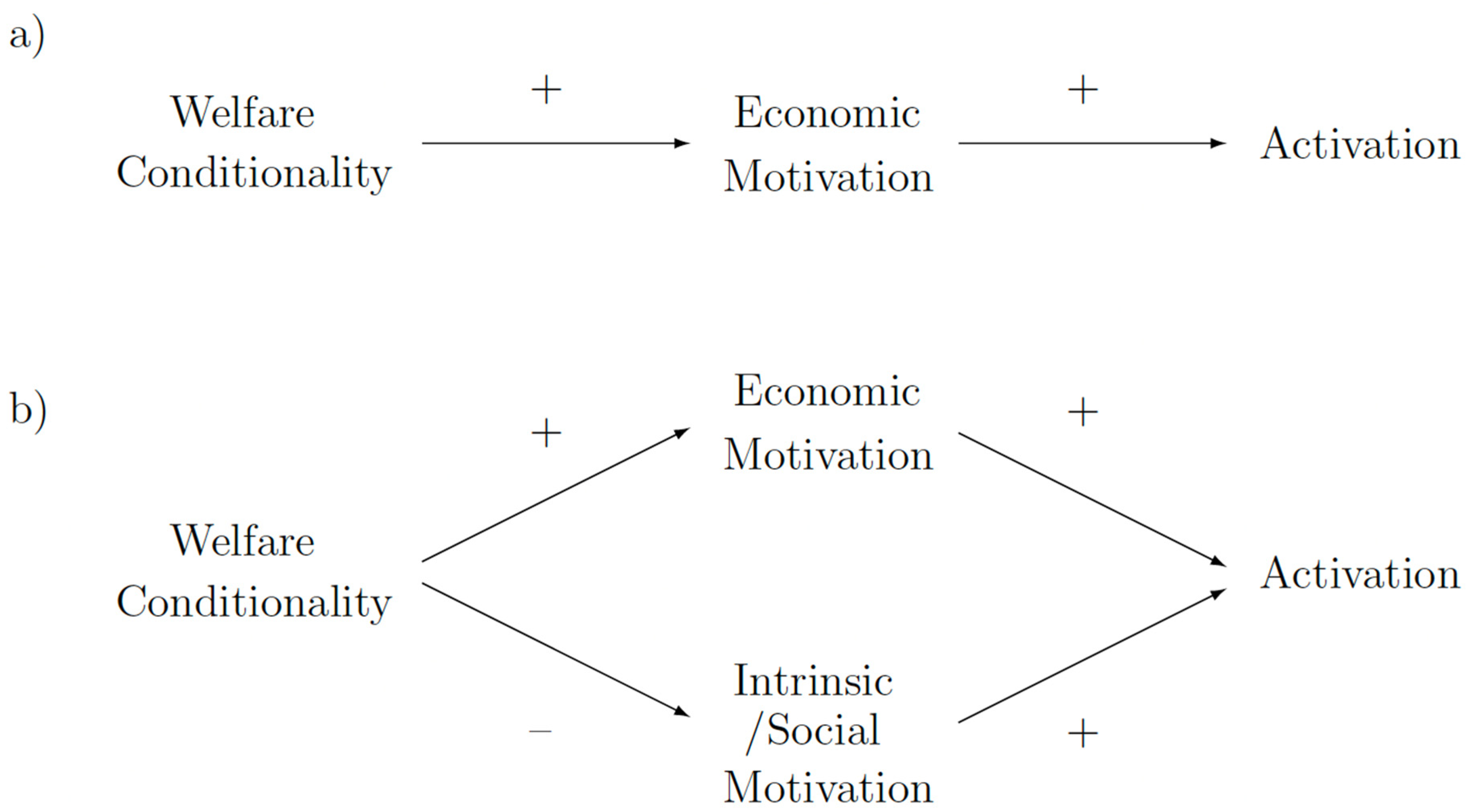

3.1. Welfare Conditionality and Activation Policies

3.2. Effects Related to Social Identity

3.3. Effects Related to Self-Determination

3.4. Example: Unemployment Support

3.5. Summing Up

4. The Case of Immigrant Support

4.1. Integration

4.2. Two Social Adversities

4.3. Effects Related to Conditional Immigrant Support

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See Giritli Nygren and Nyhlén (2017) or Nyhlén et al. (2024) for an instructive discussion focussing on examples from Sweden. |

| 2 | A satisfactory detailed integration of all the various social/social psychological and economic incentives with reasonable predictive precision so far has arguably proved elusive; for summaries of findings in behavioural economics see, for example, Camerer (2003) or Dhami (2016). For a more specific discussion of how social and social psychological incentives interact with economic ones see, for example, Bergh and Wichardt (2018) and Kemper and Wichardt (2024a). For a related critical discussion of attempts at measuring individual welfare with a focus on applications to nudging, see Kemper and Wichardt (2024b). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | The concept of social identity originated already in earlier works that later contributed to the development of social identity theory (e.g., Billig and Tajfel 1973; Tajfel 1974; Turner 1975). |

| 5 | In this respect, social identity theory is similar to self-categorisation theory, which also relies on the individual’s social identity and focuses on the question of how group behaviour originates (Turner et al. 1987). A relevant aspect here, for example, is that behaviour is based on social identity (and not personal identity) if the individual in a situation views themselves as part of the group rather than as an individual. In such instances, individual differences within the group tend to vanish as all members are viewed as more stereotypical in-group members (Turner et al. 1987). For the present purposes, however, exact differences between these theories are of minor relevance, which is why we do not follow self-categorisation theory in greater detail. |

| 6 | Inter-group conflict in the presence of a clear conflict of interest is studied in realistic conflict theory (e.g., Sherif and Sherif 1953; Sherif 1961). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Identification, for example, would still be tied to some purpose (e.g., Ryan and Deci 2022). |

| 9 | The importance of autonomy-supportive social contexts—as compared to controlling ones—for individual motivation and effective behaviour is also emphasised in Deci and Ryan (2012) or Ryan and Deci (2017, 2022). |

| 10 | Factors undermining autonomy are compulsion, manipulation, or being under the dominance of another person (e.g., Oshana 1998). |

| 11 | Note that autonomy here is not the same as freedom. If freedom to choose is limited, so is autonomy. However, I may be perfectly free to choose but still be manipulated, in which case, I would still not be autonomous (cf. Dworkin 2015); note how this relates to different levels of the internalisation of regulations/motivations (cf. Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2022). |

| 12 | For a related economic discussion, for example, focussing on the possible cost of control in an experimental labour context, see Falk and Kosfeld (2006) or Ziegelmeyer et al. (2012). |

| 13 | Arguably, such conditioning on convictions and identifications is what some politicians would like to be in place, but so far, in our view luckily, cannot be implemented. |

| 14 | |

| 15 | Arguably, even if the cited evidence suggests otherwise, a way to respond to such welfare conditionality, if associated with negative effects on belonging and relatedness, could also be to try and become more active in one’s attempt at reintegration into the labour market (as intended by the measures). Note, however, that this will be difficult in cases where unemployment is due to structural changes in the economy, reducing the supply of fitting jobs, or unfortunate personal developments, reducing one’s own abilities. In fact, particularly vulnerable groups (single parents, chronically ill people, …) may even worsen their personal situation in an exaggerated attempt at avoiding stigmatisation and identity loss. |

| 16 | For a related discussion regarding the effects of general extrinsic incentives albeit from a slightly different perspective see, for example, Frey and Jegen (2001). |

| 17 | Arguably, this may be why typical activation policies still leave room for discretion in the eventual practical implementation (e.g., Fletcher 2011). |

| 18 | We do not consider seasonal workers, etc., who keep their social roots in their home countries. |

| 19 | Different conditions (e.g., voluntary migration and forceful displacement), are likely to result, for example, in significant differences with respect to available resources as well as physical and psychological well-being when arriving in the host country. |

| 20 | For further effects of segregation on inter-group attitudes and individual development, see, for example, Mironova and Whitt (2014), Andersson and Malmberg (2018), or Scacco and Warren (2018). |

| 21 | Separation refers to the case, where cultural values are kept and interaction is avoided; marginalisation, in turn, refers to a situation where non-dominant groups experience difficulties in maintaining their culture and little interest in interaction (cf. Berry 1997, p. 9). |

| 22 | The common in-group identity model (Gaertner et al. 1989, 1993, 2016), for example, combines aspects of inter-group contact theory and identity, suggesting the creation of a joint in-group (such as the EU) to establish more positive attitudes between the groups to be integrated (e.g., France and Germany); see also Dovidio et al. (1997), Nier et al. (2001), or Dovidio et al. (2008). |

References

- Akerlof, George A., and Rachel E. Kranton. 2000. Economics and identity. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 115: 715–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, George A., and Rachel E. Kranton. 2005. Identity and the economics of organizations. Journal of Economic Perspectives 19: 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, Alberto, and Eliana La Ferrara. 2005. Ethnic diversity and economic performance. Journal of Economic Literature 43: 762–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Boston: Addison Wesley Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, Eva K., and Bo Malmberg. 2018. Segregation and the effects of adolescent residential context on poverty risks and early income career: A study of the Swedish 1980 cohort. Urban Studies 55: 365–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anteby, Michel. 2008. Identity incentives as an engaging form of control: Revisiting leniencies in an aeronautic plant. Organization Science 19: 202–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, Nicholas. 2004. The Economics of the Welfare State. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2024. Divided Arizona Contends with Trump’s Sweeping Border Plan. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c2069w5lxw5o (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Bergh, Andreas, and Philipp C. Wichardt. 2018. Accounting for context: Separating monetary and (uncertain) social incentives. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 72: 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, John W. 1991. Understanding and managing multiculturalism: Some possible implications of research in Canada. Psychology and Developing Societies 3: 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, John W. 1997. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology 46: 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, John W. 2006. Contexts of acculturation. The Cambridge Handbook of Acculturation Psychology 27: 328–36. [Google Scholar]

- Billig, Michael, and Henri Tajfel. 1973. Social categorization and similarity in intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 3: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisin, Alberto, E. Patacchini, Thierry Verdier, and Yves Zenou. 2011. Formation and persistence of oppositional identities. European Economic Review 55: 1046–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMAS. 2024. Der Asylprozess und Staatliche Unterstützung. Available online: https://www.bmas.de/DE/Arbeit/Migration-und-Arbeit/Flucht-und-Aysl/Der-Asylprozess-und-staatliche-Unterstuetzung/der-asylprozess-und-staatliche-unterstuetzung.html (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- BMJ. 2024a. Asylbewerberleistungsgestz (AsylbLG). Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/asylblg/BJNR107410993.html (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- BMJ. 2024b. Asylgesetz (AsylG), §47 Aufenthalt in Aufnahmeeinrichtungen. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/asylvfg_1992/__47.html (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- BMJ. 2024c. Asylgesetz (AsylG), §61 Erwerbstätigkeit. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/asylvfg_1992/__61.html (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Breakwell, Glynis M., A. Collie, Bennett Harrison, and Carol Propper. 1984. Attitudes towards the unemployed: Effects of threatened identity. British Journal of Social Psychology 23: 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Rupert, and Miles Hewstone. 2005. An integrative theory of intergroup contact. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 37: 255–343. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter J., and Jan E. Stets. 2009. Identity Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter J., and Judy C. Tully. 1977. The measurement of role identity. Social Forces 55: 881–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, Colin F. 2003. Behavioral Game Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel, Emma, and Theodoros Papadopoulos. 2003. The new governance of social security in Britain. In Understanding Social Security: Issues for Policy and Practice. Edited by Jane Millar. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Espen. 2003. Does ‘workfare’work? The Norwegian experience. International Journal of Social Welfare 12: 274–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Charms, Richard. 1968. Personal Causation. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, Edward L. 1971. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 18: 105–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 1985. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 2000. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11: 227–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., and Richard M. Ryan. 2012. Self-determination of theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Edited by Paul A. van Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski and Edward T. Higgins. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 416–37. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, Edward L., Gregory Betley, James Kahle, L. Abrams, and Joseph Porac. 1981. When trying to win: Competition and intrinsic motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 7: 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, Edward L., Richard Koestner, and Richard M. Ryan. 1999. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin 125: 627–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destatis. 2024. Asylbewerberleistungen—Empfängerinnen und Empfänger von Leistungen nach dem Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Soziales/Asylbewerberleistungen/Tabellen/4-3-zv-aufenthaltsrechtl-sttus-bis2019.html (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Dhami, Sanjit. 2016. The Foundations of Behavioral Economic Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, John F., Samuel L. Gaertner, Ana Validzic, Kimberly Matoka, Brenda Johnson, and Stacy Frazier. 1997. Extending the benefits of re-categorisation: Evaluations, self-disclosure and helping. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 33: 401–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovidio, John F., Samuel L. Gaertner, and Tamar Saguy. 2008. Another view of “we”: Majority and minority group perspectives on a common ingroup identity. European Review of Social Psychology 18: 296–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, Gerald. 2015. The nature of autonomy. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 1: 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Peter. 1998. Conditional citizens? Welfare rights and responsibilities in the late 1990s. Critical Social Policy 18: 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Peter. 2004. Creeping conditionality in the UK: From welfare rights to conditional entitlements? Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie 29: 265–87. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1968. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Ethier, Kathleen A., and Kay Deaux. 1994. Negotiating social identity when contexts change: Maintaining identification and responding to threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 243–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, Armin, and Michael Kosfeld. 2006. The hidden costs of control. American Economic Review 96: 1611–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Del Roy. 2011. Welfare reform, jobcentre plus and the street-level bureaucracy: Towards inconsistent and discriminatory welfare for severely disadvantaged groups? Social Policy and Society 10: 445–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, Bruno S., and Reto Jegen. 2001. Motivation crowding theory. Journal of Economic Surveys 15: 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furaker, Bengt, and Marianne Blomsterberg. 2003. Attitudes towards the unemployed. An analysis of Swedish survey data. International Journal of Social Welfare 12: 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, Samuel L., Jeffrey Mann, Audrey Murrell, and John F. Dovidio. 1989. Reducing intergroup bias: The benefits of recategorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 239–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, Samuel L., John F. Dovidio, Phyllis A. Anastasio, Betty A. Bachman, and Mary C. Rust. 1993. The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. European Review of Social Psychology 4: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, Samuel L., John F. Dovidio, Rita Guerra, Eric Hehman, and Tamar Saguy. 2016. A common ingroup identity: Categorization, identity, and intergroup relations. In Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, 2nd ed. Edited by Todd D. Nelson. New York: Psychology Press, pp. 433–54. [Google Scholar]

- Geldof, Dirk. 1999. New activation policies: Promises and risks. Linking Welfare and Work 1: 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1998. Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 2000. The Third Way and Its Critics. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giritli Nygren, Katarina, and Sara Nyhlén. 2017. Normalising welfare boundaries: A feminist analysis of Swedish municipalities’ handling of vulnerable EU citizens. T’arsadalmi Nemek Tudom’anya Interdiszciplin’aris eFoly’oirat 7: 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, V. Lee, Clifford L. Broman, William S. Hoffman, and David Rauma. 1993. Unemployment, distress, and coping: A panel study of autoworkers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65: 234–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harackiewicz, Judith M., George Manderlink, and Carol Sansone. 1984. Rewarding pinball wizardry: The effects of evaluation on intrinsic interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 47: 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, S. Alexander, Jolanda Jetten, Tom Postmes, and Catherine Haslam. 2009. Social identity, health and well-being: An emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology: An International Review 58: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, Fritz. 1958. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Heidland, Tobias, and Pilipp Wichardt. 2025. Conflicting identities: Cosmopolitan or anxious? Appreciating concerns of host country population improves attitudes towards immigrants. Social Forces 103: 1039–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewstone, Miles. 2009. Living apart, living together? The role of intergroup contact theory in social integration. Proceedings of the British Academy 162: 243–300. [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone, Miles. 2015. Consequences of diversity for social cohesion and prejudice: The missing dimension of intergroup contact. Journal of Social Issues 71: 417–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, Michael A. 2014. From uncertainty to extremism: Social categorization and identity processes. Current Directions in Psychological Science 23: 338–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, Joshua. 2016. A mod of redistribution under social identification in heterogeneous federations. Journal of Public Economics 143: 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetten, Jolanda, S. Alexander Haslam, Tegan Cruwys, Katharine H. Greenaway, Catherine Haslam, and Niklas K. Steffens. 2017. Advancing the social identity approach to health and well-being: Progressing the social cure research agenda. European Journal of Social Psychology 47: 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, Fynn, and Philipp Wichardt. 2024a. Procedurally justifiable strategies: Integrating context effects into multistage decision making. Review of Behavioral Economics 11: 313–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, Fynn, and Philipp Wichardt. 2024b. Welfare justifications and responsibility in political decision making—The case of nudging. Critical Policy Studies, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofman, Eleonore. 2005. Citizenship, migration and the reassertion of national identity. Citizenship Studies 9: 453–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepper, Mark R., and David Greene. 1975. Turning play into work: Effects of adult surveillance and extrinsic rewards on children’s intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 31: 479–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebkind, Karmela. 2001. Acculturation. In Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology. Edited by Rupert Brown and Samuel L. Gaertner. Oxford: Blackwell, vol. 4, pp. 387–405. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Padilla, Sarah, Michele J. Gelfand, Hedieh Mirahmadi, Mehreen Farooq, and Marieke Van Egmond. 2015. Belonging nowhere: Marginalization & radicalization risk among Muslim immigrants. Behavioral Science & Policy 1: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, George J. 2003. The me and the not-me: Positive and negative poles of identity. In Advances in Identity Theory and Research. Edited by Peter J. Burke, Timothy J. Owens, Richard T. Serpe and Peggy A. Thoits. New York: Plenum, pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- McGann, Michael, Phuc Nguyen, and Mark Considine. 2020. Welfare conditionality and blaming the unemployed. Administration & Society 52: 466–94. [Google Scholar]

- Mironova, Vera, and Ssam Whitt. 2014. Ethnicity and altruism after violence: The contact hypothesis in Kosovo. Journal of Experimental Political Science 1: 170–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mols, Frank, S. Alexander Haslam, Jolanda Jetten, and Niklas K. Steffens. 2015. Why a nudge is not enough: A social identity critique of governance by stealth. European Journal of Political Research 54: 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevile, Ann. 2008. Human rights, power and welfare conditionality. Australian Journal of Human Rights 14: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nier, Jason A., Samuel L. Gaertner, John F. Dovidio, Brenda S. Banker, Christine M. Ward, and Marx C. Rust. 2001. Changing interracial evaluations and behaviour: The effects of a common group identity. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 4: 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhlén, Sara, S. Skott, and Katarina Giritli Nygren. 2024. Haunting the Margins: Excavating EU Migrants as the ‘Social Ghosts’ of Our Time. Critical Criminology 32: 479–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshana, Marina A. 1998. Personal autonomy and society. Journal of Social Philosophy 29: 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, Timothy J., Dawn T. Robinson, and Lynn Smith-Lovin. 2010. Three faces of identity. Annual Review of Sociology 36: 477–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, Elizabeth Levy, Seth A. Green, and Donald P. Green. 2019. The contact hypothesis re-evaluated. Behavioural Public Policy 3: 129–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, Stefania, Fiona White, Linda Tropp, Rhiannon Turner, Elizabeth Page-Gould, Fiona Barlow, and Angel Gomez. 2021. Intergroup contact research in the 21st century: Lessons learned and forward progress if we remain open. Journal of Social Issues 77: 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, Ruth. 2014. Working on welfare: Findings from a qualitative longitudinal study into the lived experiences of welfare reform in the UK. Journal of Social Policy 43: 705–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, Thomas. 1998. Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology 49: 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piontkowski, Ursula, Arnd Florack, Paul Hoelker, and Peter Obdrzalek. 2000. Predicting acculturation attitudes of dominant and non-dominant groups. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 24: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, Aaron, and Rachel Loopstra. 2017. ‘Set up to fail’? How welfare conditionality undermines citizenship for vulnerable groups. Social Policy and Society 16: 327–38. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Katherine J., and John C. Turner. 2006. Individuality and the prejudiced personality. European Review of Social Psychology 17: 233–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Katherine J., John C. Turner, and S. Alexander Haslam. 2003. Social identity and self-categorization theories’ contribution to understanding identification, salience and diversity in teams and organizations. In Identity Issues in Groups. Edited by Jeffrey T. Polzer. Oxford: Elsevier Science, pp. 279–304. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, Morris. 1979. Conceiving the Self. Malabar: Robert E. Krieger. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Richard M. 1995. Psychological needs and facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality 62: 397–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2017. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: Guilford Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2022. Self-determination theory. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Edited by Filomena Maggino. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Richard M., Kennon Sheldon, Tim Kasser, and Edward L. Deci. 1996. All goals are not created equal: An organismic perspective on the nature of goals and their regulation. In The Psychology of Action: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behavior. Edited by Peter Gollwitzer and John A. Bargh. New York: Gulliford, pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sage, Daniel. 2012. Fair conditions and fair consequences? Exploring new Labour, welfare contractualism and social attitudes. Social Policy and Society 11: 359–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scacco, Alexsandra, and Shana S. Warren. 2018. Can social contact reduce prejudice and discrimination? Evidence from a field experiment in Nigeria. American Political Science Review 112: 654–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöb, Ronnie. 2013. Unemployment and identity. CESifo Economic Studies 59: 149–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayo, Moses. 2009. A model of social identity with an application to political economy: Nation, class, and redistribution. American Political Science Review 103: 147–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, M. 1961. Intergroup Conflict and Cooperation: The Robbers Cave Experiment. Norman: University Book Exchange. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, M., and C. W. Sherif. 1953. Groups in Harmony and Tension; an Integration of Studies of Intergroup Relations. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. 2024a. Anzahl der Abschiebungen aus Deutschland von 2007 bis 2023. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/451861/umfrage/abschiebungen-aus-deutschland/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Statista. 2024b. Anzahl der Asylanträge in Deutschland von 2014 bis 2024. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/76095/umfrage/asylantraege-insgesamt-in-deutschland-seit-1995/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Statista. 2024c. Anzahl der Ausreisepflichtigen und Geduldeten Ausländer in Deutsch-land nach Bundesländern am 31. Dezember 2023. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/671465/umfrage/ausreisepflichtige-auslaender-in-deutschland-nach-bundeslaendern/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Stephan, Walter. 2014. Intergroup Anxiety: Theory, research, and practice. Personality and Social Psychology Review 18: 239–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephan, Walter, and Cooki Stephan. 1985. Intergroup anxiety. Journal of Social Issues 41: 157–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, Jan E., and Peter J. Burke. 2003. A sociological approach to self and identity. In Handbook of Self and Identity. Edited by Mark R. Leary and June P. Tangney. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 128–52. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, Sheldon. 2000. Identity competition: Key to differential social movement involvement. In Identity, Self, and Social Movements. Edited by Sheldon Stryker, Timothy Owens and Robert W. White. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, Sheldon. 2001. Traditional symbolic interactionism, role theory, and structural symbolic interactionism: The road to identity theory. In Handbook of Sociological Theory. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Edited by Jonathan H. Turner. Boston: Springer, pp. 211–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker, Sheldon. 2002. Symbolic Interactionism: A Social Structural Version. Caldwell: Blackburn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, William B., Jr. 2012. Self-verification theory. In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology. Edited by Paul A. M. Van Lange, Arie W. Kruglanski and E. Tory Higgins. London: Sage Publications Ltd., pp. 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tagesschau. 2023. Unzufriedenheit mit Migrationspolitik Wächst. September 28. Available online: https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/deutschlandtrend/deutschlandtrend-3406.html (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Tagesschau. 2024a. Dauer der Asylverfahren 2024 Gestiegen. September 28. Available online: https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/gesellschaft/asylverfahren-dauer-2024-100.html (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Tagesschau. 2024b. Zermürbendes Warten für Ukrainische Ärzte. November 29. Available online: https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/aerzte-ukraine-anerkennung-100.html (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Tajfel, Henri. 1974. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information 13: 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 1979. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup. Edited by William G. Austin and Stephan Worchel. Monterey: Brooks/Cole, pp. 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, Henri, Michael G. Billig, Robert P. Bundy, and Claude Flament. 1971. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 1: 149–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Guardian. 2024. Anti-Immigration Mood Sweeping EU Threatens Its New Asylum Strategy. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/sep/27/anti-immigration-mood-sweeping-eu-capitals-puts-strain-on-blocs-unity (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Turner, John C. 1975. Social comparison and social identity: Some prospects for intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology 5: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, John C. 1982. Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group. In Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. Edited by Henri Tajfel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, John C., Michael A. Hogg, Penelope J. Oakes, Stephan D. Reicher, and Margaret S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. New York: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 2024a. Regional Bereau for Southern Africa Situation. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/rbsa (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- UNHCR. 2024b. Regional Bereau for West Central Africa Situation. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/rbwca (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- UNHCR. 2024c. South Sudan Situation. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/sudansituation (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- UNHCR. 2024d. Syria Situation. Available online: https://reporting.unhcr.org/operational/situations/syria-situation (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- UNHCR. 2024e. Ukraine Refugee Situation. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- van Berkel, Rik. 2010. The provision of income protection and activation services for the unemployed in ‘active’welfare states. An international comparison. Journal of Social Policy 39: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Berkel, Rik. 2020. Making welfare conditional: A street-level perspective. Social Policy & Administration 54: 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vijver, Fons J. R., Michelle Helms-Lorenz, and Max J. A. Feltzer. 1999. Acculturation and cognitive performance of migrant children in the Netherlands. International Journal of Psychology 34: 149–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oudenhoven, Jan P., Karin S. Prins, and Bram P. Buunk. 1998. Attitudes of minority and majority members towards adaptation of immigrants. European Journal of Social Psychology 28: 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts-Cobbe, Beth, and Suzanne Fitzpatrick. 2023. Advancing value pluralist approaches to social policy controversies: A case study of welfare conditionality. Journal of Social Policy 54: 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WDR. 2024. Drei von vier Deutschen Wünschen sich eine Grundsätzlich Andere Asyl und Flüchtlingspolitik. Available online: https://presse.wdr.de/plounge/tv/das%20erste/2024/09/20240905%20ard%20deutschlandtrend%20asyl-und%20fluechtlingspolitik.html (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- White, Stuart. 2000. Social rights and social contract—political theory and the new welfare politics. British Journal of Political Science 30: 507–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichardt, Philipp C. 2008. Identity and why we cooperate with those we do. Journal of Economic Psychology 29: 127–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Geoffrey C., and Edward L. Deci. 1996. Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: A test of self-determination theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70: 767–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodak, Ruth, and Salomi Boukala. 2015. (Supra) national identity and language: Rethinking national and European migration policies and the linguistic integration of migrants. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 35: 253–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Sharon. 2012. Welfare-to-work, agency and personal responsibility. Journal of Social Policy 41: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Sharon, and Ruth Patrick. 2019. Welfare conditionality in lived experience: Aggregating qualitative longitudinal research. Social Policy and Society 18: 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Sharon, Del Roy Fletcher, and Alasdair B. R. Stewart. 2020. Punitive benefit sanctions, welfare conditionality, and the social abuse of unemployed people in Britain: Transforming claimants into offenders? Social Policy & Administration 54: 278–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelmeyer, Anthony, Katrin Schmelz, and Matteo Ploner. 2012. Hidden costs of control: Four repetitions and an extension. Experimental Economics 15: 323–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, Miron, Joseph Porac, Drew Lathin, Raymond Smith, and Edward L. Deci. 1978. On the importance of self-determination for intrinsically motivated behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 4: 443–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

von Deylen, L.; Wichardt, P.C. Welfare Conditionality and Social Identity Effect Mechanisms and the Case of Immigrant Support. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14010052

von Deylen L, Wichardt PC. Welfare Conditionality and Social Identity Effect Mechanisms and the Case of Immigrant Support. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(1):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14010052

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon Deylen, Lena, and Philipp C. Wichardt. 2025. "Welfare Conditionality and Social Identity Effect Mechanisms and the Case of Immigrant Support" Social Sciences 14, no. 1: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14010052

APA Stylevon Deylen, L., & Wichardt, P. C. (2025). Welfare Conditionality and Social Identity Effect Mechanisms and the Case of Immigrant Support. Social Sciences, 14(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14010052