Abstract

(1) Background: Sustainable development goal 5.6 calls for “universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights” to fulfil sexual and reproductive practices. The capability approach helps refine the analysis of contraceptive use by going beyond the dichotomous view of contraceptive use as use/non-use to focus on women’s freedom to choose what they have good reason to value. Using the case of Burkina Faso, we probe more deeply into whether contraceptive use reflects real progress in women’s reproductive rights to realize the fertility projects they value. (2) Methods: We use PMA2020 data collected in Burkina Faso between December 2018 and January 2019. The survey included 3329 women with a participation rate of 97.7%. The PMA2020 female core questionnaire solicits information on fertility and contraceptive behavior, much like the DHS. We asked a series of specific questions about cognitive and psychosocial access relating to FP. We examined bivariate associations between our outcome measure “contraceptive behavior” and a set of independent variables. We also used logistic regression models to evaluate associations with endowments/conversion and capability factors and current functioning by focusing on overuse (i.e., use of contraceptives despite desiring pregnancy within the next 12 months). (3) Results: Women who said their ideal number of children was “up to God” had the highest level of overuse, which was also higher among women living in communities with medium acceptance of contraception and greater support for fertility. Women who have higher and middle levels of information tend to engage less in overuse than those with lower information levels. (4) Conclusions: We conclude that overuse (contraceptive use when desiring a child soon) may reveal a lack of rights, as it is associated with a lack of information about contraceptives and women’s inability to conceive an ideal number of children. Efforts should be made to enhance women’s level of contraceptive information.

1. Introduction

In Burkina Faso, according to the latest estimation, the population grew between 2006 and 2019 at a rate of 2.8% (INSD 2020), while the total fertility rate decreased from 6.2 in 2006 to 5.4 children per woman in 2015 (Ministère de la Santé 2017). While modern contraceptive prevalence was marginal in the late 1990s (4.83% in 1998), progress accelerated from 15% in 2010 to 30.7% in 2018 (PMA2020/BURKINA FASO 2019). Patterns of use have also shifted considerably toward highly effective long-acting contraceptives (e.g., implants, IUDs), which represented 51.6% of the method mix in 2016 (PMA2020/BURKINA FASO 2017). These recent changes are unexpected, given that the government’s five-year plan for reproductive health, “Plan national d’accélération de la planification familiale du Burkina Faso 2017–2020”, acknowledges that significant barriers impede the increase in contraceptive demand in the country. These barriers include the desire for large families and widespread misconceptions about modern contraceptives (Ministère de la Santé 2017). This plan aimed to increase the prevalence of modern contraceptive use from 22.5% in 2015 to 32% by 2020, amounting to an increase of 452,095 new users between 2015 and 2020 (Ministère de la Santé 2017). While policymakers and stakeholders applaud the progress, such target-driven plans may encourage coercive practices (Bendix et al. 2020; Senderowicz 2019). The focus on numerical targets may represent a step backward since the global Program of Action (POA) of the 1994 Cairo ICPD (RamaRao and Jain 2015). More specifically, targets that drive “governments to mobilize their power to raise the number of contraceptive users rather than focusing on reproductive well-being” (Peytrignet 2019, p. 17) would represent a step backward. SDG 5.6 calls for “universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights as agreed by the Program of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development and the Beijing Platform for Action and the outcome documents of their review conferences”. According to Cairo’s vision of reproductive rights (ICPD 1994), women and couples should be able to make informed decisions and have the resources to realize their fertility-related desires. Indeed, a rich body of demographic literature has examined the relationship between fertility preferences and contraceptive use through unmet needs, without truly considering reproductive rights, as contraceptive use has been considered as the goal (Raj et al. 2024). However, the capability approach calls for a greater focus on the real freedom that women have (i.e., their capabilities) to undertake actions relating to their reproductive health that allow them to lead a valuable life (Robeyns 2003).

The notion of unmet needs for contraception emerged in the 1960s (Berelson 1969; Mauldin 1965) as a gap between fertility preferences and reproductive behaviors. Critics have pointed out that the indicator is not comparable across countries owing to the significant differences in exposure to pregnancy risk relating to the frequency of intercourse. The debate also persists with respect to how pregnant or amenorrhoeic women should be considered (Bradley et al. 2012; Bradley and Casterline 2014; Rossier et al. 2015), as well as the degree to which previous pregnancies subsequently declared were wanted (Casterline and El-Zeini 2007; Gastineau et al. 2016). Moreover, classification based on past preferences, without considering the desire for avoiding further pregnancies soon, will underestimate the unmet need (Rossier et al. 2015). To settle issues of over- or underestimation through the inclusion or exclusion of specific categories, Cleland et al. (2014) said that having a valid algorithm to compare levels between countries, and over time, is crucial. However, this comparability seems questionable since underestimation and overestimation do not have the same implications between high- and low-fertility countries (Moreau et al. 2019). Moreover, many studies found that fertility preferences, which form the basis of unmet needs, can be unstable over time and are not supported by sufficient motivation. Indeed, in an analysis of data from Burkina and Ghana, Speizer found that a quarter of women who wished to limit or space out pregnancies reported that it would not be a problem if they became pregnant right away (Speizer 2006). The instability of fertility preferences may come from pregnancy postponement, defined by Timæus and Moultrie (2008) as the will to delay the next pregnancy for reasons not related to the previous birth but linked to household constraints or couple difficulties. Because these reasons can evolve quickly, any preferences based on them will be unstable.

While this demographic literature is useful in documenting the evolution of preferences, behaviors, and the mismatch between them, it does not capture a rights-centered perspective relating fertility desires to contraceptive practices and the tradeoffs that shape this association. Indeed, the capability approach offers little in the way of a demographic framework for the exploration of the relationship between women’s fertility preferences and the use or non-use of contraception. It relates an individual’s behaviors (functioning = met and unmet needs) not only, as is usual, to the resources at hand but also to their rights (capabilities) relating to determining and acting on their value-based goals. More precisely, their capabilities represent the degree to which expressed fertility preferences reflect personally endorsed choices as well as the degree to which contraceptive use (or non-use) reflects a personal choice. Existing studies on the relationship between women’s empowerment and contraceptive use proceed in this direction. However, these studies focus more on female empowerment in general (which can be construed as personal resources) than on the freedom to choose and act in terms of reproduction. The capability approach fits with this human rights perspective, which in the 1990s caused essential transformations in the perception of the demographic area by shifting “from the focus on demographic targets at the population level to improving the reproductive and sexual health of individuals, especially of girls and women” (Chiappero-Martinetti and Venkatapuram 2014, p. 717). Altogether, the capability approach goes beyond the classic frameworks of unmet needs and more recent work on female empowerment and contraception by stressing the importance of the freedom to decide and act on a fertility goal. Indeed, the DHS questionnaire includes some questions about women’s general empowerment in decision-making, violence perception, and discussion about FP. Two questions in the HIV/AIDS section of the Burkina Faso DHS female questionnaire concern the respondent’s ability to refuse sex or to ask her husband/partner to use a condom if she so wishes. The two questions related to HIV prevention may approach women’s ability to manage their reproductive behavior if we consider abstinence and condoms as the solely available contraceptives. Therefore, the classic DHS questions do not concern women’s ability to decide and take action concerning childbearing and contraceptive use.

Using original data on the psychosocial dimensions of access to contraception, this paper explores the match/mismatch between fertility preferences and contraceptive use. It revisits the old met/unmet need dichotomy, considering women's capability set—that is, their freedom to decide on their fertility goals and contraceptive practices. We evaluate how contraceptive use aligns with women’s fertility preferences and identify the factors that contribute to misalignment. We consider two types of misalignments: a desire for pregnancy avoidance coupled with non-use of contraception (the unmet need) and the use of modern contraception when women report the desire to bear a child soon. The first type of mismatch may signal a lack of resources or a lack of reliance on alternative birth control strategies (Rossier and Corker 2017). By contrast, the second type of mismatch is likely to reflect a lack of rights more clearly. We call this second mismatch “overuse”—these women may adopt contraception not because it is their wish but because it is expected following new norms or not doing so may result in pressures from partners or FP providers (Senderowicz 2019). As several studies have already examined unmet needs, we will focus on the overuse category. First, we will present the data and analysis methods. Second, we will present the bivariate and multivariate results, and third, we will discuss these results.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

This study uses a national probability survey conducted in Burkina Faso by the Institut Supérieur des Sciences de la Population (ISSP) on the Performance Monitoring and Accountability 2020 (PMA2020) platform. The current data come from Round 6, collected between December 2018 and January 2019, which includes 3329 women with a participation rate of 97.7% (https://datalab.pmadata.org/, accessed on 6 August 2019). The PMA2020 female core questionnaire solicits information on fertility and contraceptive behavior, much like the DHS. The questionnaire also includes a series of specific questions about cognitive and psychosocial access relating to FP. These new questions allow us to explore the research questions that this paper seeks to address. Our sample concerns women exposed to the risk of pregnancy, who are non-pregnant, fertile, married (which includes legally married or cohabiting), or unmarried sexually active women because our analysis focuses on current contraception use. We retained amenorrhoeic women in the sample because, apart from those using the LAM, most are not fully protected against pregnancy, according to clinical guidelines on LAM (Cleland et al. 2014).

2.2. Variables

In line with the capability framework, we use three sets of variables representing functioning, capabilities, and endowments/conversion factors. The first set concerns the functioning that relates to the current use/non-use of modern contraception, considering current fertility preferences. Modern contraception use includes the use of sterilization (female and male), tablets, intrauterine devices, injectables, implants, condoms (male and female), diaphragm, lactational amenorrhea, emergency contraception, vaginal methods (spermicide, foam, jelly), and beads. We consider the match/mismatch between the use of modern contraceptives with women’s current desires and the timing of childbearing. Fertility preferences are measured based on the desire to avoid or postpone subsequent pregnancy for more than 12 months. This 12-month cut-off point (Moreau et al. 2019), which differs from the DHS 24-month cut-off point for unmet need, is based on the addition of three months’ median time to conceive after contraception (Gnoth et al. 2003) and nine months of pregnancy. Our functioning outcome measure distinguishes four categories.

- Deliberate use: women who do not want another child or wish to postpone pregnancy for more than 12 months and are using modern contraception;

- Deliberate non-use: women who want another child within 12 months and are not using modern contraception;

- Overuse: women who want another child within 12 months but are using modern contraception;

- Unmet need: women who do not want another child or want to postpone childbearing for more than 12 months but are not using modern contraceptives.

The second set of variables represents capabilities—the opportunities of the choice and ability to act regarding fertility and contraception. These capabilities together form the freedom to engage in the contraceptive behavior that a person has reason to value. They are measured through three variables: the ability to define an ideal number of children, the ability to make decisions relating to childbearing, and the ability to make FP-related decisions (Table 1). The question regarding the ideal number of children included in the classic surveys relates to a woman’s ability to conceive the children that she wants (or would have wanted: retrospective desire for those who already have children) in her life. We recoded this ideal number into three categories: 1 = 0 to 4 children, 2 = 5 to 6 children, 3 = 7 to 25 children, and 4 = up to God or do not know. The next variables’ responses were coded 1 for the following responses: strongly disagree/disagree/doubtful. This category is defined as an inability to decide. Those who answered “agree” or “strongly agree” were coded 2 and considered able to decide. We considered those who were unable to determine a clear number of children and those unable to decide as having fewer abilities or rights.

Table 1.

List and definition of variables used.

The third group of variables represents the endowment/conversion factors that are women’s resources and characteristics—that is, factors relating to biology, resources, knowledge, skills, etc., at the individual, household, and contextual levels. They are composed of age and education, recoded into three categories: 15–24; 25–39, and 40–49 years; no education, primary education, and secondary education or above, respectively. We divided marital status into two categories: married and unmarried. We do not use parity because it correlates with age. Regarding the household-level variables, wealth is categorized into terciles. Then, we have the place of residence (urban and rural) and two social norms and customs indicators at the community level. The first is FP acceptance, defined as a combination of five questions on FP approval (Table 1). The second is the level of support for high fertility, summarizing responses to five questions about reproductive norms. We coded the responses as strongly disagree/disagree/doubtful = 0 and agree or strongly agree = 1 for each respondent. We then averaged these scores to obtain a mean score for FP acceptance and pronatalist attitudes as community-level indicators. These indicators were coded into three terciles: low, middle, and high.

We also used a method information variable constructed based on answers to the following three questions: whether the provider told the woman about other contraceptive methods; whether the provider told her about potential side effects; if “yes” was answered the latter question asked, whether the provider explained what to do upon side effect occurrence. We recoded these variables to 1 if “yes” and 0 if “no” or “not concerned”. Then, we computed the constructed variable by summing up these three items; we obtained values ranging from 0: “Low”, 1 or 2: “Middle”, and 3: “High”.

2.3. Analyses

We examined bivariate associations between our outcome measure “contraceptive behavior” and the set of independent variables. We tested the differences using chi-squared statistics with a significance level of 5%. We then conducted two multivariate analyses. For these analyses, we checked for multicollinearity among the independent variables to be used in multivariate regressions. Therefore, to reduce the number of variables in the multivariate regression, we omitted place of residence and parity because they had higher variance inflation factors than the others. We used logistic regression models to evaluate associations with endowments/conversion and capability factors and current functioning by focusing on overuse (i.e., use of contraceptives despite desiring pregnancy within the next 12 months). First, we used multilevel logistic analysis to highlight the odds ratio for a woman to engage in overuse of a modern contraceptive method. The second logistic regression aimed at analyzing a user’s likelihood of being an overuser. As this regression concerned users, we were able to control for three other variables: method information level, contraception use decision-makers, and the type of method used (short- or long-term). For each logistic analysis, we applied the step-by-step method to examine the influence of capabilities and endowments/conversion factors. Where needed, we used weights provided with the dataset. We present here the net effects of model 1 only for analysis of the entire sample and model 2 for the selected sample of modern contraceptive users.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Distribution and Prevalence of Overuse by Women’s Characteristics

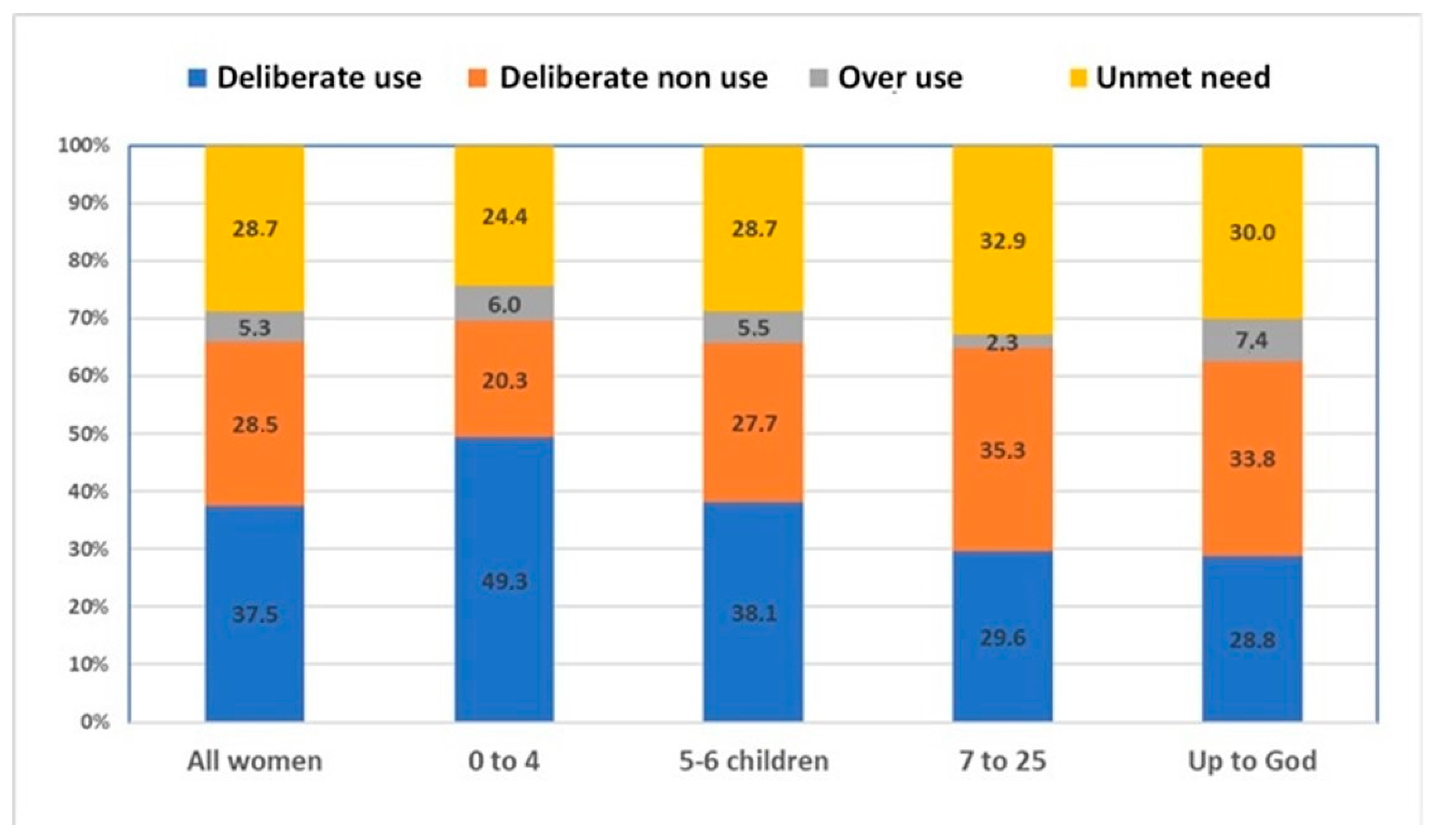

Based on our categorization of contraceptive behavior, 37.5% of women were using a modern contraceptive method and wished to delay pregnancy for more than 12 months (deliberate use) (Table 2), while 28.5% were not using contraception but did not require it (deliberate non-use). Alternatively, 5.3% of women were using a modern contraceptive method and still desired to become pregnant within the next 12 months (overuse), while 28.7% were not using contraception but wished to avoid or delay pregnancy for more than 12 months (unmet need). Thus, 66% of the women engaged in contraceptive behaviors that aligned with their fertility preferences. However, 12% of modern contraceptive users used contraception despite not needing it, and 50% of non-users “needed modern contraception” according to their fertility preferences. Regarding the ideal number of children, 26.4% of women reported wanting 0–4 children, but 17.5% had a less precise ideal number and answered that it was “up to God” or “do not know”. Two out of three women agreed that they could decide when to have a child, but only one in four thought they were able to determine their FP behavior. Most of the women in the sample (52.6%) were in the 25–39 years age group. Almost three in five women had no formal education, and only 20% had secondary level or above. Most of the women lived in rural areas (77.8%). The women were almost evenly distributed according to the wealth tercile, but the highest proportion of women (36.5%) were in the lower tercile. Fewer of them (11.9%) had no children or were unmarried. The proportions who had 1–3 children and four or more children were almost the same. The highest frequency (36%) of women was in the category of “middle acceptance of FP” in their community. However, many women (40.5%) live in communities with low fertility support.

Table 2.

Sample distribution and proportion of overusers by women’s characteristics.

Figure 1 illustrates the higher levels of congruence (deliberate use and deliberate non-use) among women who want fewer children (0–4 children). By comparison, overuse was higher among women who said it was “up to God”, while those who desired five children or more had more unmet needs.

Figure 1.

Deliberate use and overuse of contraceptives by women’s ideal number of children. Notes: data are from the Burkina PMA2020 round 6 in 2018/2019.

Women who declared that their ideal number of children was “up to God” had a higher level of overuse (7.4%) compared to those able to conceive a fixed number. Turning to the next indicator of “capabilities” (reproductive rights), women who considered themselves able to decide on the timing of their next pregnancy or the use of contraception appeared to have the same level of overuse as those who could not decide (had no rights). The proportion of overuse decreases with increasing age but increases as levels of wealth, urbanization, and education increase. It is also higher among unmarried women. Overuse was higher among women living in communities with medium acceptance of contraception and greater support for fertility.

3.2. Factors Associated with the Overuse of a Modern Contraceptive

This section examines the odds ratios (ORs) of overuse among (1) all women and (2) the group of users of modern contraception (Table 3). In the first model, women who declared that they desired fewer children engaged slightly less often in “overuse” than those who desired more children or said that it was “up to God”. We may notice that this association is statistically significant for those who were unable to give an ideal number of children. Compared to women who desire 0–4 children, those who desire more children are more likely to be overusers, but the difference is not significant. The capability variables and most other variables, such as education and age, exhibit no significant links with overuse. Higher levels of wealth are significantly associated with overuse. However, being married reduces the chances of engaging in overuse. Community levels of FP acceptance and support for fertility do not impact the likelihood of overuse among all women.

Table 3.

Odds ratios showing the net effects of independent variables on overuse.

The second model focuses on modern contraceptive users only. Let us keep in mind that the outcome variable takes 1 for women who engage in “overuse” and 0 for those who engage in “deliberate use”. Therefore, a reduced OR of overuse (in model 2) may be interpreted as a higher level of “deliberate use”. We observed the same trend for the variables “ideal number of children” and “wealth”. The relationship with marital status is no longer significant. However, a higher level of FP acceptance in the community tends to reduce the OR of overuse. No significant difference was observed in the type of contraceptive used between over-users and deliberate users. It also appears that overusers tend to make their own decisions relating to contraception use more than deliberate users. Women with higher and middle levels of information tend to engage less in overuse (OR = 0.49, 95% CI = [0.29; 0.83]) than those with lower information levels, but the relationship is not significant for women with higher information levels.

4. Discussion

The idea of match/mismatch between fertility preferences and contraceptive behavior can be conceptualized as an outcome variable that has four categories, including “unmet need” and another category, “overuse”, which has been ignored so far because all users were assumed to need contraception (Raj et al. 2024). This concept of match/mismatch better reflects reproductive freedom as stated at the Cairo Conference, as it goes beyond contraceptive use or non-use to unpack their coherence with women’s fertility desires. To maintain consistency with the median time needed for conception, we used a cut-off point of 12 months as the time required to have a child rather than 24 months, as in the unmet need algorithm.

In Burkina Faso, 30.7% of married women use modern contraception (PMA2020/BURKINA FASO 2019). However, we used a sample of women exposed to the risk of pregnancy; that is, married (legally of cohabiting), non-pregnant, fertile, unmarried, and sexually active women aged 15–49 years. Our results indicate that contraceptive behavior in Burkina Faso generally reflects a high level of human rights—that is, a match between fertility desire and contraceptive use. However, many users have freedom in their behavior while most non-users do not. Almost two out of five women are using modern contraception in accordance with their reproductive desires (i.e., “deliberate use”). Among the users, only one in 10 uses a modern method contrary to her fertility desires—that is, while also expressing a wish to become pregnant again soon. The “overuse” of modern contraception (i.e., when it does not match with fertility desire) appears to be characteristic of women who are less committed to their fertility desires. It is less often observed among women who have larger or unclear ideal numbers of children. Thus, in this case, contraception use does not align with the desire to avoid pregnancy. It appears more related to women’s ambivalence about childbearing.

The ambivalent nature of fertility preferences may make the assessment of both unmet needs and overuse of contraception difficult. In fact, some studies have noted that fertility preferences can be unstable over time because some women with unmet needs have been found to be loosely committed to their fertility preferences (Casterline et al. 1997) or to have perceived themselves as at low risk of pregnancy, as noted by Westoff and Bankole (1995). So, ambivalent fertility desires may cause a mismatch owing to the weakness in fertility motivations, particularly if these motivations are contrary to the dominant contextual views (Machiyama et al. 2017). In the case of overuse, the ambivalence of fertility preferences may be explained by the idea of postponement as defined by Timæus and Moultrie (2008), as the desire to delay birth may be related to unstable causes. The current use of modern contraception may have been decided based on causes that may have evolved at the time of the interview.

We may also consider the diffusion of new behaviors among those who are more open-minded and have the means to afford those contraceptives. In fact, wealthier women are more likely to be in urban settings, where modern contraceptives are widespread. Wealthier urban women may have more interaction with the healthcare system because many studies show that poverty reduces the access to maternal healthcare (Ononokpono et al. 2013; McNamee et al. 2009). Additionally, systematic FP counseling for women receiving non-FP healthcare services has been shown to increase contraceptive use (Grubb et al. 2018). Therefore, wealthier urban women may not only have easier access to FP but also higher overall healthcare utilization, leading to more opportunities for accessing FP. This could suggest that “overuse” may be associated with women who have greater access to health services in general, and to FP services in particular.

Some may think that most “overusers” may be more likely to use short-term contraceptives to avoid sexually transmitted diseases, but the results suggest that overusers are more likely to equally use the two method types (short-term or long-term). The results also show that overusers are more likely to independently decide to use contraception. However, the results do not support the likelihood of explicit coercion through force or violence as found in some literature (Silverman and Raj 2014; Grace and Anderson 2018). Additionally, overusers tend to be less well-informed about contraceptive methods, which may be due to inadequate or biased counseling, as observed in other studies (Senderowicz 2019; Solo and Festin 2019). Indeed, the lack of relevant information portrays a lack of contraceptive autonomy (Senderowicz 2020) and may induce women to use contraceptives unnecessarily or for longer than necessary in regard to their fertility needs.

Another explanation may be the limited access to FP services to remove their contraceptives, especially for long-term ones. The lack of removal or a limited access to FP services can force a woman use a long-term contraceptive method longer than necessary. Quality care requires that providers respect patient preferences for the removal of long-term methods without imposing administrative, financial, or medical barriers (Strasser et al. 2017; Howett et al. 2019; Wollum et al. 2024). Such barriers, which may discourage women from using long-term methods, could be seen as another form of coercion and might explain some instances of overuse. However, this hypothesis does not seem to hold true here because overusers are equally using long-term and short-term contraceptives. We may also consider the change in their fertility desire between the time they began using the contraceptive method and the date of the survey. We lack the data to verify this hypothesis here. The drawbacks to this situation may include the sense of a delay in the return of fertility.

Previous research has shown that some women tend to use some contraceptive methods for reasons not related to fertility, especially for aesthetic reasons (Drabo 2020). In this case, the demand for contraceptive products beyond family planning may also stem from a mismatch between contraceptive practice and fertility desires. Other studies have shown that contraceptives are used to shape and control the body’s capacities, reduce premenstrual pain and headaches, stop menstrual flow, and gain weight (Boydell 2010; Sanabria 2016; Teixeira et al. 2015).

We improved the questionnaire by including questions about women’s ability to decide on fertility and contraceptive use (Zan et al. 2024), as many reviews show that such questions are often missing in empowerment and FP frameworks (Raj et al. 2024). However, our analysis had some limitations. The dataset is not as large as the DHS’s datasets and does not allow for detailed statistical calculations and significance. Furthermore, applied only once, it does not allow for highlighting the evolution of indicators over time. Another limitation is the lack of additional questions about the inconsistency between the declaration of contraceptive use and the desire to have children soon. This question would have helped to correct one of the declarations. Indeed, desirability bias may have induced some of the respondents to say that they were using a contraceptive method or that they were willing to bear a child soon. Moreover, this study lacks data on the counselling process in health centers. To address this, we rely on other studies that highlight the existence of biased or directive counselling that tends to encourage clients to use contraceptive methods in similar settings (Senderowicz 2019).

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to highlight the relationship between women’s reproductive rights and contraceptive behavior in Burkina Faso, where the rapid growth in modern contraceptive prevalence makes people wonder about the possible violation of women’s rights. Therefore, we applied the capability approach, which—like the human rights-based approach—focuses on people’s rights to determine and realize their choices. This approach allowed us to refine our analysis of the factors associated with fertility desires and contraceptive behaviors by considering reproductive rights (capabilities) rather than analyzing contraception use only.

As many studies have analyzed unmet needs, we focused on the second type of mismatch—“overuse”—that combines modern contraceptive use with a desire to have a child soon. From a human rights-based perspective, we conclude that overusers lack two types of rights. The first type of right is the ability to conceive a concise fertility project, to decide and to act regarding FP. This first lack may be caused by sociocultural or religious norms that may not allow them to exercise autonomy concerning reproductive matters. The second type of right concerns the availability of relevant information about the contraceptives they are using. Overuse may be satisfactory for those who are focused on modern contraception use as a goal. However, this behavior does not match women’s reproductive rights and well-being, particularly in this case where they lack information about contraceptive methods. Indeed, sufficient counselling is needed, particularly for those who are using a contraceptive method. In this sense, FP strategies and services must reinforce deliberate and informed contraceptive choices. Importantly, each user must know when to cease using contraception to time their next pregnancy. The three-month median duration between the time to stop using and the time to get pregnant must be considered and told to women so that they can stop at the appropriate time. Doing so will reduce the number of women who experience a long delay in their fertility’s return after ceasing modern contraception use.

In summary, the mismatch of overuse means that current contraception use, in some cases, may not indicate a current wish to avoid pregnancy. This mismatch concerns women who have easy access to modern contraceptives, who do not have a clear ideal number of children, and who are less informed about contraceptives. In summary, “overuse” does not align with the principles of human rights-based FP services as recommended by the 1994 Cairo POA. Our results suggest that the counselling process must give women the necessary information to help them decide intentionally on their use of contraception. Providers should inform users about modern contraception, including the duration of the action of contraceptives and when to stop using, according to their fertility preferences.

Further analysis using larger datasets is required, which must include variables on women’s reproductive freedom and more detailed community and health facility characteristics. As it may portray ambivalent fertility preferences, the FP survey questionnaires must ask additional questions of respondents who report that they are using a contraceptive method and desire to become pregnant soon. Another approach could be to monitor the issue using the recent PMA longitudinal data to observe how overuse evolves yearly and whether it remains confined to the same categories of women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.Z. and C.S.-D.; methodology, M.L.Z.; software, M.L.Z.; validation, M.L.Z.; formal analysis, M.L.Z.; investigation, M.L.Z. and C.R.; resources, C.R.; data curation, M.L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.L.Z., C.R. and C.S.-D.; visualization: M.L.Z., C.R. and C.S.-D.; supervision, C.R.; project administration, C.R.; funding acquisition, C.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research, carried out as part of a PhD study, received support from the Swiss Confederation under Grant 2017.750.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethic Committee Name: Comité d'éthique pour la recherche en santé Approval Code: CERS-N°2018-11-140. Approval Date: 7 November 2018.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The original data base is available on https://datalab.pmadata.org/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bendix, Daniel, Ellen E. Foley, Anne Hendrixson, and Susanne Schultz. 2020. Targets and technologies: Sayana Press and Jadelle in contemporary population policies. Gender, Place & Culture 27: 351–69. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, Bernard. 1969. Beyond family planning. Studies in Family Planning 1: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boydell, Victoria Jane. 2010. The Social Life of the Pill: An Ethnography of Contraceptive Pill Users in a Central London Family Planning Clinic. London: London School of Economics and Political Science (United Kingdom). [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, Sarah E.K., and John B. Casterline. 2014. Understanding unmet need: History, theory, and measurement. Studies in Family Planning 45: 123–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, Sarah E.K., Trevor N. Croft, Joy D. Fishel, and Charles F. Westoff. 2012. Revising Unmet Need for Family Planning. Calverton: ICF. [Google Scholar]

- Casterline, John B., A. E. Perez, and A. E. Biddlecom. 1997. Factors underlying unmet need for family planning in the Philippines. Studies in Family Planning 28: 173–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casterline, John B., and Laila O. El-Zeini. 2007. The estimation of unwanted fertility. Demography 44: 729–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappero-Martinetti, Enrica, and Sridhar Venkatapuram. 2014. The capability approach: A framework for population studies. African Population Studies 28: 708–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland, John, Sarah Harbison, and Iqbal H. Shah. 2014. Unmet Need for Contraception: Issues and Challenges. Studies in Family Planning 45: 105–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabo, Seydou. 2020. Beyond ‘family planning’—Local realities on contraception and abortion in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Social Sciences 9: 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastineau, Bénédicte, Lina Rakotoson, and Frédérique Andriamaro. 2016. L’indicateur des Objectifs du Millénaire pour le développement. Mondes en Développement 2: 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoth, C., D. Godehardt, E. Godehardt, P. Frank-Herrmann, and G. Freundl. 2003. Time to pregnancy: Results of the German prospective study and impact on the management of infertility. Human Reproduction 18: 1959–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, Karen Trister, and Violence Jocelyn C. Anderson. 2018. Reproductive coercion: A systematic review. Trauma, & Abuse 19: 371–90. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, Laura K., Rebecca M. Beyda, Mona A. Eissa, and Laura J. Benjamins. 2018. A contraception quality improvement initiative with detained young women: Counseling, initiation, and utilization. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 31: 405–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howett, Rebecca, Alida M. Gertz, Tiroyaone Kgaswanyane, Gregory Petro, Lesego Mokganya, Sifelani Malima, Tshego Maotwe, Melanie Pleaner, and Chelsea Morroni. 2019. Closing the gap: Ensuring access to and quality of contraceptive implant removal services is essential to rights-based contraceptive care. African Journal of Reproductive Health 23: 19–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- ICPD. 1994. International Conference on Population and Development-ICPD-Programme of Action. New York: UNFPA. [Google Scholar]

- INSD. 2020. Résultats Préliminaires du 5e RGPH. Available online: http://cns.bf/IMG/pdf/rapport_preliminaire_rgph_2019.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Machiyama, Kazuyo, John B. Casterline, Joyce N. Mumah, Fauzia Akhter Huda, Francis Obare, George Odwe, Caroline W. Kabiru, Sharifa Yeasmin, and John Cleland. 2017. Reasons for unmet need for family planning, with attention to the measurement of fertility preferences: Protocol for a multi-site cohort study. Reproductive Health 14: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauldin, W. P. 1965. Fertility studies: Knowledge, attitude, and practice. Studies in Family Planning 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamee, Paul, Laura Ternent, and Julia Hussein. 2009. Barriers in accessing maternal healthcare: Evidence from low-and middle-income countries. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research 9: 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Santé. 2017. Plan National d’Accélération de Planification Familiale du Burkina Faso 2017–2020. Available online: http://www.healthpolicyplus.com/ns/pubs/8212-8375_PNAPF.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Moreau, Caroline, Mridula Shankar, Stephane Helleringer, and Stanley Becker. 2019. Measuring unmet need for contraception as a point prevalence. BMJ Global Health 4: e001581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ononokpono, Dorothy Ngozi, Clifford Obby Odimegwu, Eunice Imasiku, and Sunday Adedini. 2013. Contextual determinants of maternal health care service utilization in Nigeria. Women & Health 53: 647–68. [Google Scholar]

- Peytrignet, Marie-Claire. 2019. Fertility Regulation in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Role of Marital Sexual Inactivity. Ph.D. thesis, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- PMA2020/BURKINA FASO. 2017. Résumé des Principaux Indicateurs en Planification Familiale Pour la 4ème Vague de Collecte. Baltimore: John Hopkins. [Google Scholar]

- PMA2020/BURKINA FASO. 2019. Key Family Planning Indicators: December 2018—January 2019 (Round 6). Baltimore: John Hopkins. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, Anita, Arnab Dey, Namratha Rao, Jennifer Yore, Lotus McDougal, Nandita Bhan, Jay G. Silverman, Katherine Hay, Edwin E. Thomas, Rebecka Lundgren, and et al. 2024. The EMERGE framework to measure empowerment for health and development. Social Science & Medicine 351: 116879. [Google Scholar]

- RamaRao, Saumya, and Anrudh K. Jain. 2015. Aligning goals, intents, and performance indicators in family planning service delivery. Studies in Family Planning 46: 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2003. Sen’s capability approach and gender inequality: Selecting relevant capabilities. Feminist Economics 9: 61–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossier, Clémentine, and Jamaica Corker. 2017. Contemporary Use of Traditional Contraception in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review 43: 192–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossier, Clémentine, Sarah E. Bradley, John Ross, and William Winfrey. 2015. Reassessing unmet need for family planning in the postpartum period. Studies in Family Planning 46: 355–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanabria, Emilia. 2016. Plastic Bodies: Sex Hormones and Menstrual Suppression in Brazil. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Senderowicz, Leigh. 2019. “I was obligated to accept”: A qualitative exploration of contraceptive coercion. Social Science & Medicine 239: 112531. [Google Scholar]

- Senderowicz, Leigh. 2020. Contraceptive autonomy: Conceptions and measurement of a novel family planning indicator. Studies in Family Planning 51: 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, Jay G., and Anita Raj. 2014. Intimate partner violence and reproductive coercion: Global barriers to women’s reproductive control. PLoS Medicine 11: e1001723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solo, Julie, and Mario Festin. 2019. Provider bias in family planning services: A review of its meaning and manifestations. Global Health: Science and Practice 7: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speizer, Ilene S. 2006. Using strength of fertility motivations to identify family planning program strategies. International Family Planning Perspectives 32: 185–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, Julia, Liz Borkowski, Megan Couillard, Amy Allina, and Susan F. Wood. 2017. Access to removal of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods is an essential component of high-quality contraceptive care. Women’s Health Issues 27: 253–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, Maria, Nathalie Bajos, and Agnès Guillaume. 2015. l’équipe ECAF. 2015 De la Contraception Hormonale en Afrique de l’Ouest: Effets Secondaires et Usages à la Marge. Paris: Anthropologie du Médicament au Sud. La Pharmaceuticalisation à ses Marges, pp. 181–95. [Google Scholar]

- Timæus, Ian M., and Tom A. Moultrie. 2008. On postponement and birth intervals. Population and Development Review 34: 483–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westoff, Charles F., and Akinrinola Bankole. 1995. Unmet Need: 1990–1994. Calverton: Macro International. [Google Scholar]

- Wollum, Alexandra, Corrina Moucheraud, Amon Sabasaba, and Jessica D. Gipson. 2024. Removal of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods and quality of care in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Client and provider perspectives from a secondary analysis of cross-sectional survey data from a randomized controlled trial. PLOS Global Public Health 4: e0002810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zan, Lonkila Moussa, Clémentine Rossier, and Caroline Moreau. 2024. Zan, Lonkila Moussa, Clémentine Rossier, and Caroline Moreau. 2024. Measuring Cognitive and Psychosocial Accessibility to Modern Contraception: A Comprehensive Framework. Health 16: 578–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).