Abstract

Background: Research in psychology has attempted to identify the main predictors and strategies that are useful to promote well-being. Although personality has been recognized as one of the main determinants of well-being, the primary mechanisms involved in this relationship are not fully disclosed. This research addressed the impact of pro-environmental behaviors in the interplay between the Big Five (openness, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism) and psychological well-being (eudaimonic). Methods: A total of 176 young adults (mean age = 21.55 years; SD age = 1.76 years; 114 F; mean education = 14.57 years; SD = 2.11 years) participated in this study. The participants were requested to complete a short battery of self-report questionnaires, including the Big Five Inventory-10, the Pro-environmental Behavior Questionnaire, and the Psychological Well-being Scale. Results: The results revealed that pro-environmental behaviors only mediated the association between agreeableness and eudaimonic well-being (B = 2.25, BootSE = 1.26, BootCIs 95% [0.149, 5.050]). Conclusions: These findings contributed to identifying the potential mechanisms through which personality contributes to individual eudaimonic well-being, also providing insights into the development of promoting interventions based on eco-sustainable behaviors. Limitations and future research directions are discussed.

1. Introduction

Psychological well-being (PWB) is a core construct of mental health, concerning optimal psychological functioning and experience (Dhanabhakyam and Sarath 2023; Tang et al. 2019; Ryff 2014; Gigantesco et al. 2011). Psychological research has sought to identify predictors and strategies to promote PWB given that its realization represents one of the primary purposes in an individual’s life, especially in terms of mental and emotional health. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PWB is a state of mind in which an individual is able to develop their potential, work productively and creatively, and cope with the normal stresses of life (World Health Organization 2021). From the eudaimonic standpoint (Waterman et al. 2010), PWB encompasses various aspects. These include nurturing positive social connections, fostering personal growth and advancement, cultivating a positive sense of self-worth and acceptance, experiencing a sense of control over one’s own life, exercising self-determination and independence, and having the freedom to select or shape environments that align with one’s psychological state (Dhanabhakyam and Sarath 2023). The PWB elements are interconnected and function collectively to enhance overall well-being, surpassing the mere absence of mental illness. They enable individuals to experience greater fulfilment, contentment, and happiness in life (Ryff 1989).

The PWB construct plays a protective role against several illnesses and disabilities through the optimal regulation of various physiological and neurological systems. Ryff et al. (2015) found that a high level of well-being is linked to better subjective health. Participants in the study reported fewer chronic conditions, less symptoms, and lower functional disability. Additionally, PWB is linked to lower cardiovascular mortality in healthy populations and decreased death rates in patients with conditions such as renal failure and HIV infection (Chida and Steptoe 2008). These findings show that having a positive mindset can affect physical health. This means that PWB should be achieved by all individuals at any age. Several studies have consistently demonstrated a strong connection between PWB and successful ageing (Fusi et al. 2022; Boccardi and Boccardi 2019; Steptoe et al. 2015). Low levels of PWB were also found to be positively correlated to mortality (Matud et al. 2019).

PWB is a multidimensional construct that reflects the eudaimonic dimension of well-being, involving personal development and growth as the realization of individual potential (Ryff and Singer 1996). PWB can be defined through six dimensions (Ryff and Singer 1996): self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, and purpose in life (Ryff and Singer 1996; Lamers et al. 2011). Specifically, the most recurrent dimension of well-being is self-acceptance, which is associated with important personal characteristics such as self-actualization, optimal functioning, and maturity (Ryff and Singer 1996). Self-acceptance can also refer to having a positive attitude toward oneself and one’s past experiences, recognizing and accepting one’s own characteristics (Matud et al. 2019). Additionally, PWB is also described as involving strong feelings of empathy and affection for all human beings, as well as the capability for greater love, deeper friendships, and more complete identification with others. This characteristic represents the dimension of positive relationships with others (Ryff and Singer 1996) and refers to having satisfactory interpersonal relations. Autonomy involves self-determination, independence, and the regulation of behavior from within, whereas environmental mastery can be defined as the individual’s ability to choose or create environments that are suitable for their personal conditions, and taking advantage of the opportunities the environment offers to fulfill one’s needs and values (Matud et al. 2019). Personal growth indicates continual development rather than achieving a fixed state, and having the feeling that one is developing one’s own potential. Finally, purpose in life indicates a clear comprehension of one’s life, a sense of directedness, and intentionality, all of which contribute to the feeling that life is meaningful (Matud et al. 2019).

Although previous studies have shown that some personality traits, such as the Big Five (i.e., Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism) can explain individual differences in PWB (Bojanowska and Urbańska 2021; Hautekiet et al. 2022), the main factors affecting this interplay remain underexplored. This study advanced the hypothesis that personality impacts PWB via pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs). On the one hand, the propensity to engage in PEBs may be influenced by individual personality traits. For example, individuals exhibiting high levels of agreeableness and openness may be more predisposed to recognize the detrimental effects of environmental issues on society, thereby leading them to adopt PEBs (Anglim et al. 2020), which contribute to the greater social good within the community. On the other hand, prior research suggests that PEBs can contribute to individuals’ sense of personal satisfaction and fulfillment (Kasser 2017). Thus, it is plausible to consider PEBs as a mediator of the association between personality and PWB, given that taking care of the environment encompasses both attitudes to sociability and well-being practices toward both the others and the environment.

1.1. Personality and Psychological Well-Being

Personality seems to play a key role in affecting PWB, given that previous studies have shown that these two constructs are strongly related (de Vos et al. 2022; Sun et al. 2018; Anglim et al. 2020). The literature agrees that personality traits affect how individuals experience, approach, and appraise their lives (DeNeve and Cooper 1998; Headey and Wearing 1989; Steel et al. 2008). Personality can be considered as an individual variable involving biological, social, and intrapsychic factors that determine, cause, and explain behaviors (Giancola et al. 2023b). This definition describes the three levels at which personality can be analyzed: traits, characteristic adaptations, and life stories (DeYoung 2010). Costa and McCrae (1992) suggested that various aspects of personality may impact well-being. Certain traits facilitate well-being, and in some cases, the data turned out to be so consistent that researchers (Costa and McCrae 1992; Costa et al. 2019) coined the term “happy personality” to denote the configurations of traits that facilitate well-being (Bojanowska and Urbańska 2021). Most of the studies examining the personality correlates of PWB focused on the Big Five or the Five-Factor Model (Anglim et al. 2020; Goldberg 1993; DeYoung et al. 2016), which suggests that five broad factors typically appear in the analyses of any sufficiently broad pool of personality descriptors. The Big Five dimensions are: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Openness involves curiosity and creativity. Conscientiousness includes self-discipline and respect for duty, as well as persistence in reaching a predetermined goal. Extraversion relies on dynamism and sociability, while agreeableness entails friendship and social acquiescence. Finally, neuroticism includes emotional instability, defined in terms of anxiety, insecurity, fearfulness, and anger.

More specifically, although personality is undoubtedly related to PWB in somehow, research provided mixed results. A handful of studies underlined the predictive role of neuroticism, extraversion, and conscientiousness (Anglim et al. 2020; Grant et al. 2009). Lower levels of neuroticism as well as higher levels of conscientiousness and extraversion appear to be associated with better PWB profiles (Rzeszutek et al. 2019). However, some studies indicated that openness to experience and agreeableness are critical in explaining variance in PWB (Anglim et al. 2020). Probably, these mixing results rely on the complexity of the relationship between personality traits and PWB, which reflects behaviors that individuals intentionally adopt to enhance both personal and social well-being.

1.2. Personality and Pro-Environmental Behaviors

PEBs represent a set of deliberate, effective, and anticipatory actions focused on caring for the environment (Pavalache-Ilie and Cazan 2018). Examples of environmentally friendly behaviors include saving energy and water, cutting down on plastic use, composting food waste, recycling, properly disposing of waste, and choosing sustainable products. Evidence suggests that individuals’ characteristics may enable some to respond to climate change productively, while leading to maladaptive responses for others (Mathers-Jones and Todd 2023). Many of these environmentally friendly behaviors could be predicted by psychological factors, such as attitudes and personality traits. Several studies have indicated that openness represents one of primary determinants of PEBs (Brick and Lewis 2016), including aspects such as environmental intentions, goals, or self-reported behavior. Indeed, intellectual curiosity and flexibility enable individuals to actively engage in understanding the impact of human actions on nature and envisage solutions for preserving the natural environment (Hirsh and Dolderman 2007). Yet, openness also promotes alternative thinking, which has been associated with environmentalism (Brick and Lewis 2016). In addition, some facets of agreeableness, such as empathy and altruistic behavior, were positively associated with PEBs (Soto and John 2009). Consistent with these results, Markowitz et al. (2012) found that individuals with higher levels of openness to experience and agreeableness show a greater positive interest in the environment, which is characterized by traits such as intellectual curiosity and empathy. Regarding the association between the other three Big Five personality traits and PEBs, research has provided misleading results with positive, negative, or even non-significant associations (Brick and Lewis 2016; Poškus and Žukauskienė 2017); thus, their involvement in affecting PEBs is not entirely clear.

1.3. Pro-Environmental Behaviors and Psychological Well-Being

Interestingly, in recent years, a growing research literature has indicated that PEBs can affect the well-being construct in its different facets; indeed, frequent engagement in PEBs is positively correlated with PWB (Kasser 2017). According to Kasser’s (2017) review, participating in PEBs leads to the satisfaction of psychological needs, subsequently contributing to overall well-being (Brown and Kasser 2005; Jacob et al. 2009). In addition, Kasser and Sheldon (2002) suggested that a happy life may align with a more ecologically sustainable lifestyle. In their intriguing research conducted during the Christmas holiday, the authors demonstrated that American adults and young adults reported higher levels of well-being in the two weeks around Christmas when they engaged in more environmentally friendly practices (e.g., giving environmentally friendly or charitable gifts, using organic or locally grown foods). Thus, Kasser and Sheldon’s (2002) study provides evidence that well-being, measured in terms of life satisfaction and the experience of pleasant versus unpleasant emotions, is positively associated with PEBs. This body of evidence, even though it is not directly related to PWB but rather to subjective well-being, suggests that PEBs might support also PWB. The relationship between PEBs and PWB could be explained with the Self-Determination Theory, which suggests that individuals experience higher well-being when they satisfy their needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Ryan and Deci 2000). Specifically, competence needs are satisfied when individuals can engage successfully in valued behavior. Relatedness needs are satisfied when individuals feel close to and accepted by others. Autonomy needs are satisfied when individuals choose to engage in a behavior rather than feeling compelled to do so. Thus, we can deduce that engaging in PEBs helps to satisfy individuals’ psychological needs, improving the levels of PWB (Ryan and Deci 2000).

1.4. The Present Study

The present study explored the association between personality and PWB, considering the role of PEBs.

Based on the evidence that openness to experience and agreeableness are associated with PEBs (Markowitz et al. 2012; Anglim et al. 2020) and given the findings stressing the role of PEBs in triggering individuals’ PWB (Ryan and Deci 2000), this study advanced two mediation models. The first model addressed the mediating role of PEBs in the association between openness to experience and PWB. For this model, this study stressed the view that PEBs serve as a mechanism through which openness to experience positively affects PWB. Indeed, individuals showing high levels of openness to experience are more prone to engage in PEBs due to their appreciation for nature and concerns for environment issues (Pavalache-Ilie and Cazan 2018). By actively participating in eco-green practices, these individuals, on the one hand, contribute to safeguarding the natural environment and its sustainability; on the other hand, they experience a sense of fulfilment and connection with the natural environment, which in turn, enhances their PWB. This notion aligns with a considerable set of research indicating that the preference for eco-green behaviors positively predicted PWB, meaning that individuals who engage eco-green practices and adopt a green lifestyle tend to experience better sense of PWB (Carrero et al. 2020; Gao et al. 2020). Given this mechanism, the first hypothesis (H1) was advanced as follows: The individual disposition toward PEBs mediates the association between openness to experience and PWB.

The second model explored the mediating role of PEBs in the interplay between agreeableness and PWB. This model relies on the view that individuals with high levels of agreeableness usually show high empathy, compassion, and concern for the welfare of others, as well as a higher disposition toward cooperative and pro-social behaviors (Hilbig et al. 2014) that could also involve concerns about the sustainability of the natural environment. Based on these eco-green concerns, individuals with a high agreeableness may engage in PEBs. In turn, these practices could lead them to experience a sense of altruism, social connectedness, and personal fulfilment, which, in turn, enhances PWB. Hilbig et al. (2014) suggested that agreeableness, as conceptualized within the Five-Factor Model, is the personality trait that is most predictive of cooperation. Indeed, agreeableness is conceptually linked to moral norms, pro-social behaviors, and cooperative attitude (Hilbig et al. 2014), and in this perspective, PEBs can be considered as cooperative behaviors. Based on this logic, the second hypothesis (H2) was formulated as follows: The individual disposition toward PEBs mediates the association between agreeableness and PWB.

Given this logic for both mediation models, PEBs act as a bridge through which individuals with a high openness to experience and agreeableness can experience high levels of PWB.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Data were collected using an online survey disseminated across different social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. Before starting the survey, subjects were presented with an online informed consent page detailing the purpose, the study duration, and the inclusion (minimum age of 18 years) and exclusion (visual impairments; language difficulties; psychological disorders, including depression, anxiety; and so forth) criteria. The survey consisted of two sections: the first section gathered socio-demographic information, such as age, gender, and education, while the second section involved completing a battery of self-report questionnaires. The latter included the Big Five Inventory-10 (Guido et al. 2015), the Pro-Environmental Behavior Questionnaire (Tapia-Fonllem et al. 2012), and the Psychological Well-being Scale (Ryff 1989).

A total of 176 Italian individuals, with a mean age of 21.55 years (SD = 1.76 years) participated in the study, of whom 114 (64.8%) were female and the remaining 62 were male (35.2%). In terms of education, participants reported the following educational levels: middle school diploma (0.6%), high school diploma (56.8%), bachelor’s degree (30.1%), master’s degree (10.2%), and specialization (2.3%). Participants were selected if they did not report diagnosis of psychological problems, including depression, anxiety, or neurological diseases. No rewards were provided for taking part in this study, and total anonymity was guaranteed. All participants signed an informed consent before participating in the online survey. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of L’Aquila (protocol number: 124809).

2.2. Measures

The Big Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10; Guido et al. 2015) consists of 10 items (e.g., “I see myself as someone who has an active imagination) on a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree). This measure assesses the Big Five personality traits, namely agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism (hereafter emotional stability), extraversion, and openness. The BFI-10 was used in different web-design studies for short online surveys, showing good psychometric properties (e.g., Coco et al. 2021; Giancola et al. 2023c). As in previous research, the Spearmen–Brown coefficient was used to evaluate the internal consistency (Eisinga et al. 2013), which, in this research, was as follows: agreeableness (ρ = 0.62), conscientiousness (ρ = 0.57), emotional stability (ρ = 0.76), extraversion (ρ = 0.67), and openness (ρ = 0.50).

The Pro-Environmental Behavior Questionnaire (PEBQ; Tapia-Fonllem et al. 2012; Giancola et al. 2021a) is a brief questionnaire adapted from Kaiser’s (1998) General Ecological Behavior Scale, which consists of 16 items on a four-point Likert-type scale (0 = never; 3 = always). The PEBQ assesses the frequency of PEB in participants’ everyday life, including reuse, recycling, and conserving resources. In previous research, this instrument showed good psychometric properties (e.g., Giancola et al. 2021a), and in the present study, the internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s α = 0.77).

The Psychological Well-being Scale (PWBS; Ryff 1989) includes 84 items with a six-point Likert scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). Psychological well-being was measured by summing the scores of all items (after recording the reverse items), and individuals with higher scores in the PWBS were considered to have higher levels of psychological well-being. In previous research, the PWBS showed good psychometric properties (Marrero-Quevedo et al. 2019) and, in the current research, the internal consistency was very good (Cronbach’s α = 0.95)

Socio-demographic information. Age, gender, and educational level were collected.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The SPSS Statistics version 24 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, NY, USA) was used to analyze the data. Preliminarily, descriptive statistics and correlations were computed to evaluate the main features and the associations among all study variables. The mediation analysis was computed using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 3.5; Hayes 2017). In PROCESS, the mediation effect is denoted by a significant 95% confidence interval (CI) bootstrapped based on 5000 samples. The bootstrapping approach provides an accurate evaluation of the mediating and moderating effects in small- to medium-sized samples (e.g., Giancola et al. 2022c, 2023d). The significance of the results is provided if the range of the bootstrapped CI does not include the value of zero (Preacher and Hayes 2008; Giancola et al. 2023a). In the bootstrapping approach, the R2 value represents a measure of the effect size. All significance was set to p < 0.05.

3. Results

As concerns the preliminary analysis, the normality test revealed that the variables of interest were not normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test: ZAgreebleness = 0.04, sig; ZCoscientiousnes = 0.00, sig; ZEmotional Stability = 0.01, sig; ZExttraversion= 0.01, sig; ZOpenness = 0.01, sig), except for the PEBs and well-being (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test: ZPEBs = 0.37, ns; ZWell-being = 0.23, sig). No univariate outliers were found using the z-test, with −4.0 and +4.0 z-scores as cut-offs for samples larger than 100 (Giancola 2022; Mertler and Vannatta 2005). Table 1 reports the preliminary correlation analysis.

Table 1.

Correlational analysis among study variables.

The preliminary correlations indicated a lack of correlation between PEBs and conscientiousness (r = 0.10, p > 0.05), emotional stability (r = −0.14, p > 0.05), and extraversion (r = 0.09, p > 0.05). Then, we performed two mediation models. Model A included openness to experience as the independent variable, PEBs as the mediator, and psychological well-being as the dependent variable. Model B included agreeableness as the independent variable, PEBs as the mediator, and PWB as the dependent variable. Note that the correlational analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between openness to experience and agreeableness (r = 0.22, p < 0.01). Consequently, agreeableness was entered as a covariate in Model A, while openness to experience was included as a covariate in Model B.

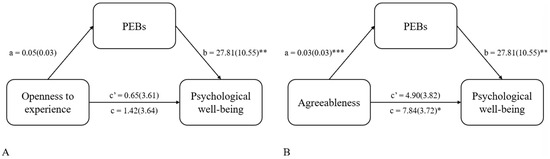

Entering openness to experience as the independent variable, the mediation analysis indicated that openness to experience was not associated with PEBs (B = 0.05, p > 0.05), which, however, predicted PWB (B = 27.81, p < 0.01). These findings suggested that PEBs did not mediate the association between openness to experience and PWB (B = 1.35, SE = 0.95, BootCIs 95% [−0.137, 3.523]). The direct effect of openness to experience on PWB was not significant (B = 0.07, p > 0.05), as well as the total effect (B = 1.41, p > 0.05).

Including agreeableness as the independent variable, the mediation analysis revealed that agreeableness was associated with PEBs (B = 0.11, p < 0.001), which predicted PWB (B = 27.81, p < 0.01). These findings suggested that PEBs mediated the association between agreeableness and PWB (B = 2.94, SE = 1.52, BootCIs 95% [0.525, 6.471]). The direct effect of agreeableness on PWB was not significant (B = 4.90, p > 0.05), whereas the total effect was significant (B = 7.84, p < 0.01). Figure 1 summarizes the results of the two mediation models.

Figure 1.

Summary of the mediating effects of PEBs with openness to experience (Model A) and agreeableness (Model B) as the independent variables. Note. * p < 0.05 (two tailed). ** p < 0.01 (two tailed). *** p < 0.001 (two tailed).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the involvement of pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) in the association between personality traits and psychological well-being (PWB). In accordance with the Self-Determination Theory, we hypothesized that environmentally friendly behaviors, influenced by personality characteristics, can provide individuals with a sense of satisfaction and self-determination, thereby promoting PWB. Indeed, in line with the Self-Determination Theory, behavioral change is related to intrinsic motivation, which is facilitated by the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs, i.e., competence, relatedness, and autonomy. When an individual is able, via their concrete actions and practices, to satisfy these needs, their well-being increases (Flannery 2017). This means that if the individual engages in positive behaviors in their living environment, which are appreciated by others, they fulfill the need for competence, relationships, and autonomy (Ryan and Deci 2000). In this vein, some personality traits would play a key role, representing a plausible antecedent of positive behaviors. Different studies have found that openness to experience and agreeableness are highly associated with PWB (Anglim et al. 2020). In turn, the individual disposition toward practices aimed at caring for the natural environment, as well as the connection to nature and access to green space, were found to positively impact individuals’ experience of PWB (Tian et al. 2023).

With this in mind, this study investigated the role of openness to experience and agreeableness on PWB, with a focus on the mediating effect of PEBs. The findings rejected H1 and confirmed H2, revealing that PEBs exclusively mediated the relationship between agreeableness and PWB (Model B), while no mediating effect was observed in the interplay between openness to experience and PWB (Model A).

Regarding the mediating role of PEBs in the association between agreeableness and PWB (Model B), it is likely that agreeableness relates to PWB via PEBs based on attention toward others and altruism (Graziano et al. 2007), as well as friendship and social acquiescence (DeYoung et al. 2016). Indeed, DeYoung et al. (2016) showed that environmental and prosocial behaviors, such as community participation, provide intrinsic satisfaction that bolsters personal well-being. Soto and John (2009) demonstrated positive correlations between some facets of agreeableness, such as empathy and altruistic behavior, and PEBs. In addition, Wang and collaborators (Wang et al. 2019) showed that agreeableness modulates risk-taking behavior and brain activity when individuals make decisions in groups, which could have implications for sustainability group behavior. Specifically, Wang and collaborators (Wang et al. 2021) demonstrated that a group’s values motivate individual pro-environmental practices by strengthening individuals’ environmental self-identity—the degree to which individuals see themselves as environmentally friendly (Triandis 1988). This might be particularly true in the Italian culture (Burton et al. 2021), where individuals are more likely to act in line with their group’s interests than in the American culture. In other words, perceived group values may promote pro-environmental behavior (Triandis 1988). Burton et al. (2021) showed that groups of Italian peers function as a group with shared goals and expectations of mutual helping behavior. Therefore, individuals with personality traits characterized by altruism and cooperative behavior may be more inclined to motivate the groups they belong to and adopt sustainable behavior toward the environment, which can consequently endeavor PWB. It is noteworthy that agreeableness is a trait closely linked to affect- and emotion-control processes, resulting in agreeable individuals regulating their behavior in a socially acceptable manner (Wang et al. 2019). Thus, individuals with a high agreeableness are more likely to actively engage in activities that benefit the environment, such as volunteering for environmental causes or taking part in community clean-up initiatives; they are more prone to engage in cooperative and compassionate behaviors, which often translate into proactive efforts to safeguard the natural world.

Notably, the lack of mediating effect of PEBs in the association between openness to experience and PWB needs to be clarified. One explanation could be that individuals with high levels of openness to experience tend to be more prone to seek novel experiences or engage in creative practices (Tan et al. 2019) that may not necessarily translate into environmentally friendly actions, leading to a weaker or non-existent mediating effect of PWB.

Despite this evidence, the current research shows some limitations, which opens new avenues for future research. First, this study was cross-sectional and did not provide an indication of causality. Future research should confirm the mediating role of PEBs using a longitudinal design, as well as test alternative models to better explore the mechanisms underpinning PWB.

Second, in this research, PEBs were evaluated using only a self-report measure. In order to obtain a more ecological evaluation, future research should also consider performance tasks to measure individuals’ preference toward practices that are aimed at caring for the natural environment. Third, the current study assessed individual differences considering only the Big Five model. Even though this represents the most popular personality taxonomy in the psychology of personality, the Big Five model only provides a partial picture of personality. Future research should consider other personality taxonomies, as well as different individual features such as cognitive styles (Giancola et al. 2021b, 2022b). Forth, given that PEBs and PWB can be affected by a series of common virtues, such as wisdom, creativity, and knowledge, as well as courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence (Giancola et al. 2022a; Corral-Verdugo et al. 2015), future research should control for these variables when detecting the mediating mechanisms underlying the association between personality and PWB. Finally, well-being was explored only considering the eudaimonic facet. Future research should also consider the subjective facet. Indeed, several studies have suggested that individuals with high levels of openness experience happiness, a positive effect, and quality of life, and these could be significant predictors of subjective well-being across different age groups (Costa and McCrae 1992; Dong and Ni 2020). Additionally, Kasser and Sheldon (2002) showed that subjective well-being is positively associated with PEBs.

5. Conclusions

Psychological well-being (PWB) is one of the main goals that many individuals seek to achieve in their lives, but it necessitates consistent actions and respectful conduct toward themselves and others. For this reason, scientific research is moving to understand the factors that can lead individuals to find their optimal state of well-being. The literature agrees that personality traits are strongly linked to PWB (de Vos et al. 2022; Sun et al. 2018; Anglim et al. 2020). Moreover, PEBs are also systematically associated with PWB. Consistent with the idea that pro-environmental practices reflect both personality attributes and individuals’ well-being states, the present study found that PEBs fully mediated the association between agreeableness and PWB. This means that PWB indirectly reflects sociability and friendship attitudes through individuals’ perceptions regarding the enactment of respectful conduct toward one’s environment. This study reveals a new approach that has been rarely discussed in the literature. Further research on this topic could lead to more accurate explanations and interpretations regarding the determinants of well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.P., M.G., M.S., S.D. and M.P.; methodology, M.G.; formal analysis, M.G.; investigation, M.G.; resources, M.P.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.P.; writing—review and editing, M.C.P., M.G., M.S., S.D. and M.P.; supervision, M.P.; project administration, M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding by the Department of Biotechnological and Applied Clinical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, 67100 L’Aquila, Project code: 07_DG_2024_13.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of L’Aquila (protocol code 44/2021; date of approval 26 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anglim, Jeromy, Sharon Horwood, Luke D. Smillie, Rosario J. Marrero, and Joshua K. Wood. 2020. Predicting psycho logical and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 146: 279–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccardi, Mariangela, and Virginia Boccardi. 2019. Psychological wellbeing and healthy aging: Focus on telomeres. Geriatrics 4: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bojanowska, Agnieszka, and Beata Urbańska. 2021. Individual values and well-being: The moderating role of personality traits. International Journal of Psychology 56: 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brick, Cameron, and Gary J. Lewis. 2016. Unearthing the “Green” personality. Environment and Behavior 48: 635–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Kira W., and Tim Kasser. 2005. Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of vaues, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research 74: 349–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Leslie, Elisa Delvecchio, Alessandro Germani, and Claudia Mazzecchi. 2021. Individualism/collectivism and personality in Italian and American Groups. Current Psychology 40: 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero, Isabel, Carmen Valor, and Racuel Redondo. 2020. Do all dimensions of sustainable consumption lead to psychological well-being? Empirical evidence from young consumers. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 33: 145–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, Yoichi, and Andrew Steptoe. 2008. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: A quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine 70: 741–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coco, Marinella, Claudia S. Guerrera, Giuseppe Santisi, Febronia Riggio, Roberta Grasso, Donatella Di Corrado, Santo Di Nuovo, and Tiziana Ramaci. 2021. Psychosocial impact and role of resilience on healthcare workers during COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 13: 7096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corral-Verdugo, Victor, Tapia-Fonllem Cesar, and Ortiz-Valdez Anais. 2015. On the relationship between character strengths and sustainble behavior. Environment and Behavior 47: 877–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Paul T., and Robert R. McCrae. 1992. The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality dis orders. Journal of Personality Disorders 6: 343–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Paul T., Jr., Robert R. McCrae, and Corinne E. Löckenhoff. 2019. Personality Across the Life Span. Annual Review Psychology 70: 423–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vos, Jan A., Mirjam Radstaak, Ernst T. Bohlmeijer, and Gerben J. Westerhof. 2022. Exploring associations be tween personality trait facets and emotional, psychological and social well-being in eating disorder patients. Eating and Weight Disorders 27: 379–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeNeve, Kristina M., and Harris Cooper. 1998. The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 142: 197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeYoung, Colin G. 2010. Personality neuroscience and the biology of traits. Social Personal 4: 1165–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, Colin G., Bridget E. Carey, Robert F. Krueger, and Scott R. Ross. 2016. Ten aspects of the Big Five in the Personality Inventory for DSM-5. Personality Disorder 7: 113–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanabhakyam, Dhana M., and M. Sarath. 2023. Psychological wellbeing: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology 3: 603–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Rui, and Shi G. Ni. 2020. Openness to Experience, Extraversion, and Subjective Well-Being Among Chinese College Students: The Mediating Role of Dispositional Awe. Psychological Reports 123: 903–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinga, Rob, Manfred T. Grotenhuis, and Ben Pelzer. 2013. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health 58: 637–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannery, Marie. 2017. Self-Determination Theory: Intrinsic Motivation and Behavioral Change. Oncology Nursing Forum 44: 155–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusi, Giulia, Massimiliano Palmiero, Sara Lavolpe, Laura Colautti, Maura Crepaldi, Alessandro Antonietti, Domenico Di Alberto, Barbara Colombo, Adolfo Di Crosta, Pasquale La Malva, and et al. 2022. Aging and Psychological Well-Being: The Possible Role of Inhibition Skills. Healthcare 10: 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Jian, Jianguo Wang, and Jianming Wang. 2020. The impact of pro-environmental preference on consumers’ perceived well-being: The mediating role of self-determination need satisfaction. Sustainability 12: 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco. 2022. Who complies with prevention guidelines during the fourth wave of COVID-19 in Italy? An empirical study. Personality and Individual Differences 199: 111845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancola, Marco, Alessia Bocchi, Massimiliano Palmiero, Ilaria De Grossi, Laura Piccardi, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2023a. Examining cognitive determinants of planning future routine events: A pilot study in school-age Italian children (Análisis de los determinantes cognitivos de la planificación de eventos de rutina futuros: Un estudio piloto con niños italianos en edad escolar). Studies in Psychology 44: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Maria C. Pino, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2021a. Exploring the psychosocial antecedents of sustain able behaviors through the lens of the positive youth development approach: A Pioneer study. Sustainability 13: 12388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Massimiliano Palmiero, Alessia Bocchi, Laura Piccardi, Raffaella Nori, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2022a. Divergent thinking in Italian elementary school children: The key role of probabilistic reasoning style. Cognitive Processing 23: 637–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Massimiliano Palmiero, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2022b. Field dependent–independent cognitive style and creativity from the process and product-oriented approaches: A systematic review. Creativity Studies 15: 542–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Massimiliano Palmiero, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2022c. Social sustainability in late adolescence: Trait Emotional Intelligence mediates the impact of the Dark Triad on Altruism and Equity. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 840113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancola, Marco, Massimiliano Palmiero, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2023b. Dark Triad and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: The role of conspiracy beliefs and risk perception. Current Psychology 31: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Massimiliano Palmiero, and Simonetta D’Amico. 2023c. The green adolescent: The joint contri bution of personality and divergent thinking in shaping pro-environmental behaviours. Journal of Cleaner Production 417: 138083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Simonetta D’Amico, and Massimiliano Palmiero. 2023d. Working Memory and Divergent Thinking: The Moderating Role of Field-Dependent-Independent Cognitive Style in Adolescence. Behavioral Sciences 13: 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancola, Marco, Verde Paola, Cacciapuoti Luigi, Angelino Gregorio, Piccardi Laura, Bocchi Alessia, Palmiero Massimiliano, and Nori Raffaella. 2021b. Do Advanced Spatial Strategies Depend on the Number of Flight Hours? The Case of Military Pilots. Brain Sciences 11: 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigantesco, Antonella, Maria A. Stazi, Guido Alessandri, Emanuela Medda, Emanuele Tarolla, and Corrado Fagnani. 2011. Psychological well-being (PWB): A natural life outlook? An Italian twin study on heritability of PWB in young adults. Psychological Medicine 41: 2637–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, Lewis R. 1993. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist 48: 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, Sharon, Janice Langan-Fox, and Jeromy Anglim. 2009. The big five traits as predictors of subjective and psychological well-being. Psychological Reports 105: 205–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, William G., Meara M. Habashi, Brad E. Sheese, and Renèe M. Tobin. 2007. Agreeableness, empathy, and helping: A person x situation perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93: 583–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guido, Gianluigi, Alessandro M. Peluso, Mauro Capestro, and Mariafrancesca Miglietta. 2015. An Italian version of the 10-item Big Five Inventory: An application to hedonic and utilitarian shopping values. Personality and In Dividual Differences 76: 135–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautekiet, Pauline, Nelly D. Saenen, Dries S. Martens, Margot Debay, Johan Van der Heyden, Tim S. Nawrot, and Eva M. De Clercq. 2022. A healthy lifestyle is positively associated with mental health and well-being and core markers in ageing. BMC Medicine 20: 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Headey, Bruce, and Alexander Wearing. 1989. Personality, life events, and subjective well-being: Toward a dynamic equilibrium model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 731–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbig, Benjamin E., Andreas Glöckner, and Ingo Zettler. 2014. Personality and prosocial behavior: Linking basic traits and social value orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107: 529–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, Jacob B., and Dan Dolderman. 2007. Personality predictors of consumerism and environmentalism: A pre liminary study. Personality and Individual Differences 43: 1583–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, Jacob, Emily Jovic, and Merlin B. Brinkerhoff. 2009. Personal and planetary well-being: Mindfulness medita tion, pro-environmental behavior and personal quality of life in a survey from the social justice and ecological sustainability movement. Social Indicators Research 93: 275–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Florian G. 1998. A general measure of ecological behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 28: 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, Tim. 2017. Living both well and sustainably: A review of the literature, with some reflections on future re search, interventions and policy. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 375: 20160369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasser, Tim, and Kennon M. Sheldon. 2002. What makes for a merry Christmas? Journal of Happiness Studies 3: 313–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, Sara M. A., Gerben J. Westerhof, Ernst T. Bohlmeijer, Peter P. M. Ten Klooster, and Corey L. M. Keyes. 2011. Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF). Journal of Clinical Psychology 67: 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markowitz, Ezra M., Lewis R. Goldberg, Michael C. Ashton, and Kibeom Lee. 2012. Profiling the “pro-environ mental individual”: A personality perspective. Journal of Personality 80: 81–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marrero-Quevedo, Rosario J., Pedro J. Blanco-Hernández, and Juan A. Hernández-Cabrera. 2019. Adult attachment and psychological well-being: The mediating role of personality. Journal of Adult Development 26: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers-Jones, Jordon, and Jemma Todd. 2023. Ecological anxiety and pro-environmental behaviour: The role of at tention. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 98: 102745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, Pilar M., Marisela López-Curbelo, and Demelza Fortes. 2019. Gender and Psychological Well-Being. International Journal Environmental Research Public Health 16: 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertler, Craig A., and Rachel A. Vannatta. 2005. Advanced and Multivariate Statistical Methods: Practical Application and Interpretation (3.Basm). Glendale: Pyrczak Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Pavalache-Ilie, Mariela, and Ana M. Cazan. 2018. Personality correlates of pro-environmental attitudes. International Journal Environmental Health Research 28: 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poškus, Mykolas S., and Rita Žukauskienė. 2017. Predicting adolescents’ recycling behavior among different big five personality types. Journal of Environmental Psychology 54: 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and com paring indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, Richard M., and Edward L. Deci. 2000. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist 55: 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D. 1989. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 1069–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D. 2014. Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 83: 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, Carol D., and Burton Singer. 1996. Psychological well-being: Meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 65: 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol D., Barry T. Radler, and Elliot M. Friedman. 2015. Persistent psychological well-being predicts improved self-rated health over 9–10 years: Longitudinal evidence from MIDUS. Health Psychology Open 2: 2055102915601582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeszutek, Marcin, Ewa Gruszczyńska, and Ewa Firląg-Burkacka. 2019. Socio-Medical and Personality Correlates of Psychological Well-Being among People Living with HIV: A Latent Profile Analysis. Applied Research in Quality of Life 14: 1113–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, Christopher J., and Oliver P. John. 2009. Ten facet scales for the Big Five inventory: Convergence with NEO PI-R facets, self-peer agreement, and discriminant validity. Journal of Research in Personality 43: 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Piers, Joseph Schmidt, and Jonas Shultz. 2008. Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin 134: 138–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, Andrew, Angus Deaton, and Arthur A. Stone. 2015. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 385: 640–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Jessie, Scott B. Kaufman, and Luke D. Smillie. 2018. Unique Associations between Big Five Personality Aspects and Multiple Dimensions of Well-Being. Journal of Personality 86: 158–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Chee-Seng, Xian S. Lau, Yian T. Kung, and Renu A.L. Kailsan. 2019. Openness to experience enhances creativity: The mediating role of intrinsic motivation and the creative process engagement. The Journal of Creative Behavior 53: 109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Yi Y., Rongxiang Tang, and James J. Gross. 2019. Promoting Psychological Well-Being Through an Evidence-Based Mindfulness Training Program. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 13: 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia-Fonllem, Cesar, Victor Corral-Verdugo, Blanca Fraijo-Sing, and Maria F. Durón-Ramos. 2012. Assessing sus tainable behavior and its correlates: A measure of pro-ecological, frugal, altruistic and equitable actions. Sustainability 5: 711–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Haibo, Yajun Qiu, Yeqiang Lin, and Wenting Zhou. 2023. Personality and subjective well-being among elder adults: Examining the mediating role of cycling specialization. Leisure Sciences 45: 117–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, Harry C. 1988. Collectivism v. Individualism: A reconceptualisation of a basic concept in cross-cultural so cial psychology. In Personality, Cognition and Values: Cross-Cultural Perspectives of Childhood and Adolescence. Edited by C. Bagley and G. K. Verma. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 60–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Fang, Xin Wang, Fenghua Wang, Li Gao, Hengyi Rao, and Yu Pan. 2019. Agreeableness modulates group member risky decision-making behavior and brain activity. Neuroimage 202: 116100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiao, Ellen Van der Werff, Thijs Bouman, Marie K. Harder, and Linda Steg. 2021. I Am vs. We Are: How Bio spheric Values and Environmental Identity of Individuals and Groups Can Influence Pro-environmental Be haviour. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 618956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, Alan S., Seth J. Schwartz, Byron L. Zamboanga, Russell D. Ravert, Michelle K. Williams, Bede B. Agocha, Su Y. Kim, and Brent M. Donnellan. 2010. The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology 5: 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2021. Mental Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/major-themes/health-and-well-being (accessed on 12 January 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).