Abuse in Chilean Trans and Non-Binary Health Care: Results from a Nationwide Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

Brief Contextualization

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The National Trans and Non-Binary Health Survey (Chile)

2.2. The Sample

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

3.2. Experiences of Abuse in Trans and Non-Binary Health Care

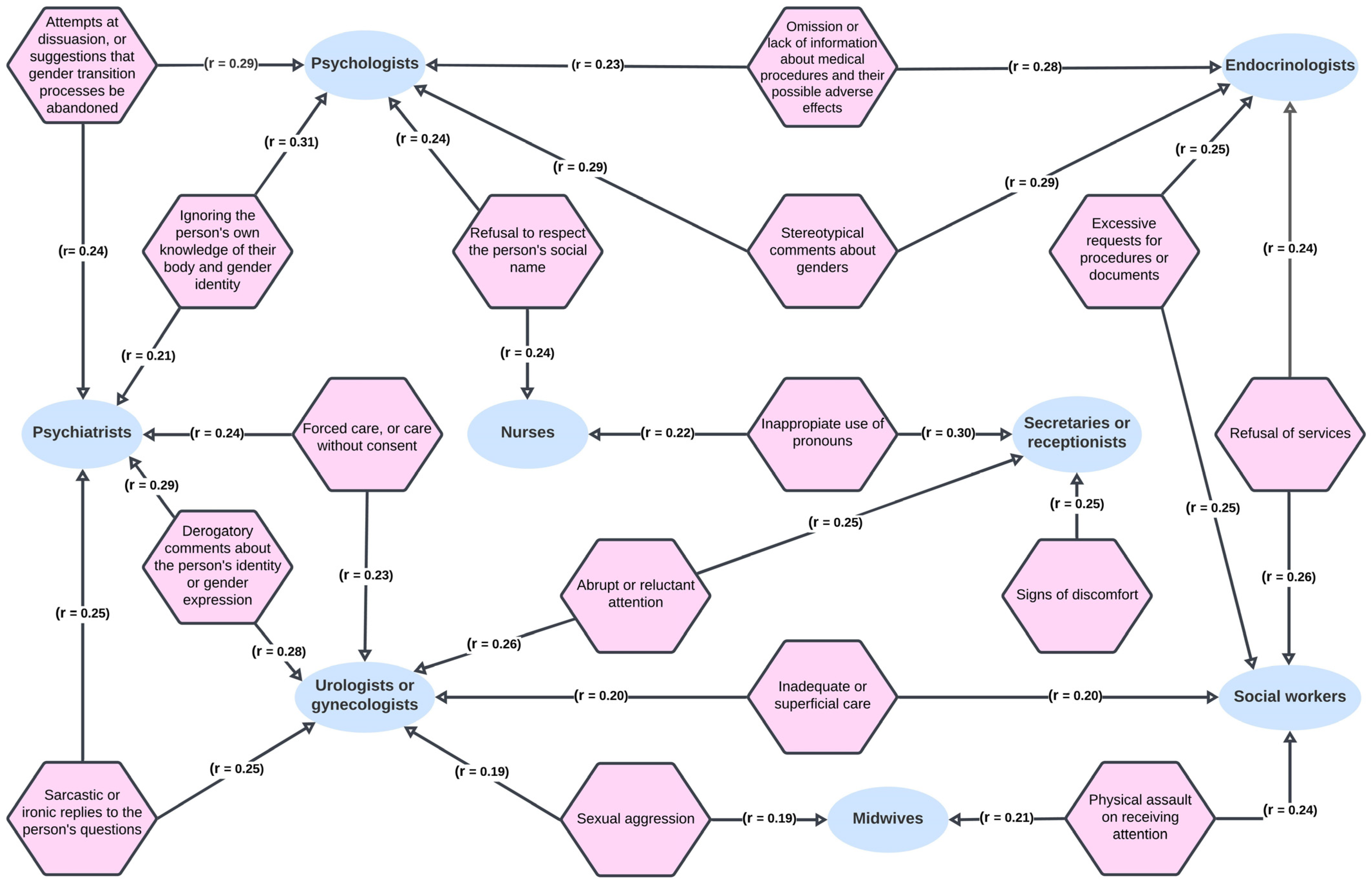

3.3. Health Personnel Associated with Abuse in Trans and Non-Binary Health Care

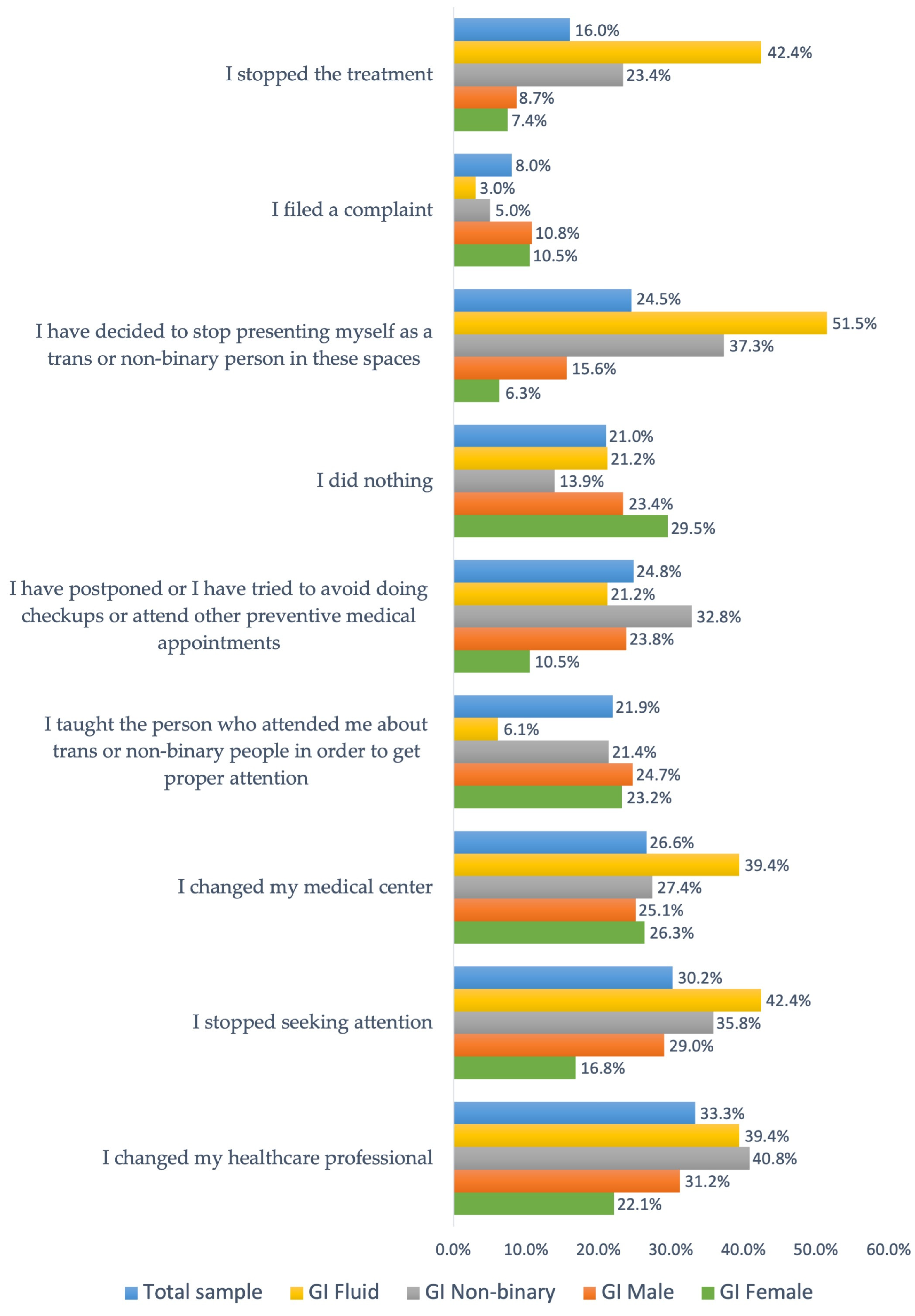

3.4. Responses to Experiences of Abuse in Trans and Non-Binary Health Care

4. Discussion

Limitations and Projections

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ansara, Gavriel, and Peter Hegarty. 2012. Cisgenderism in psychology: Pathologizing and misgendering children from 1999 to 2008. Psychology & Sexuality 3: 137–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, Ashley, and Goodman Revital. 2018. Perceptions of transition-related health and mental health services among transgender adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 30: 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, Cemile Hurrem Balik, Ozgu Tekin Uluman Hülya Bilgin, Sevil Yilmaz Ozge Sukut, and Sevim Buzlu. 2020. A Systematic Review of the Discrimination Against Sexual and Gender Minority in Health Care Settings. International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services 50: 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzer, Carsten, and Jan Simon Hutta. 2013. Transrespeto versus transfobia en el mundo: Un estudio comparativo de la situación de los derechos humanos de las personas Trans [Transrespect vs. Transphobia in the World: A Comparative Study of the Human Rights Situation of Trans People]. Berlín: TvT Publications, Transgender Europe Transrespeto versus Transfobia en el Mundo [Transgender Europe and transrespect vs. trasphobia in the world]. Available online: https://transrespect.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/TvT_research-report_ES_.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Barrientos, Jaime. 2016. Situación social y legal de gays, lesbianas y personas transgénero y la discriminación contra estas poblaciones en América Latina [The social and legal status of gay men, lesbians and transgender persons, and discrimination against these populations in Latin America]. Sexualidad, Salud y Sociedad (Rio de Janeiro) 22: 331–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Greta R., Rebecca Hammond, Robb Travers, Matthias Kaay, Karin M. Hohenadel, and Michelle Boyce. 2009. ‘I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives’: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC 20: 348–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlant, Lauren, and Michael Warner. 1998. Sex in Public. Critical Inquiry 24: 547–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookfield, Samuel, Judith Dean, Candi Forrest, Jesse Jones, and Lisa Fitzgerald. 2019. Barriers to accessing sexual health services for Transgender and Male sex workers: A systematic qualitative meta-summary. AIDS and Behavior 24: 682–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüggemann, A. Jelmer, and Katarina Swahnberg. 2013. What contributes to abuse in health care? A grounded theory of female patients’ stories. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50: 404–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüggemann, Adrianus Jelmer, Barbro Wijma, and Katarina Swahnberg. 2012. Abuse in health care: A concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 26: 123–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, Jelmer, Alma Persson, and Barbro Wijma. 2019. Understanding and preventing situations of abuse in health care. Navigation work in a Swedish palliative care setting. Social Science & Medicine 222: 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, Stephanie L., Jill L. Adelson, and Kimberly A. S. Howard. 2013. Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 81: 545–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, Diana, Richard Lee, Alisia Tran, and Michelle Van Ryn. 2008. Effects of perceived discrimination on mental health and mental health services utilization among gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender persons. Journal of LGBT Health Research 3: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalán, Manuel. 2018. Principales barreras de acceso a servicios de salud para personas lesbianas, gay y bisexuales [Main barriers to accessing health services for lesbian, gay and bisexual people]. Cuadernos Médicos Sociales 58: 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Eli, Asa Radix, Walter Bouman, George Brown, Annelou de Vries, Madeline Deutsch, Randi Ettner, Lin Fraser, Michael Goodman, Jamison Green, and et al. 2022. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health 23: S1–S260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, Raewyn. 2009. Gender: In World Perspective. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn. 2012. Gender, health and theory: Conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Social Science & Medicine 74: 1675–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crissman, Halley, Daphna Stroumsa, Emily Kobernik, and Mitchell Berger. 2019. Gender and frecuent mental distress: Comparing Transgender and Non-Transgender individuals’ self-rated mental health. Journal of Women’s Health 28: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- División de Desarrollo Institucional. Gobierno de Chile. 2020. Informe CDD: Caracterización sociodemográfica y socioeconómica en la población asegurada inscrita [Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Characterization of the Insured and Affiliated Population]. Departamento de Estadística. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiGpfDu5IyCAxXtJrkGHd1fAbQQFnoECCMQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.fonasa.cl%2Fsites%2Ffonasa%2Fadjuntos%2FInforme_caracterizacion_poblacion_asegurada&usg=AOvVaw2g5FpcmT6MzHiW12k5gwxq&opi=89978449 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Finley, Charles. 2020. Paternalism and Autonomy in Transgender Healthcare. Honors Thesis, Butler University, Indianapolis, IN, USA, May 4. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, Susan, Richard S. Lazarus, Christine Dunkel-Schetter, Anita DeLongis, and Rand J. Gruen. 1986. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50: 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, Karen I., Loree Cook-Daniels, Hyun-Jun Kim, Elena A. Erosheva, Charles A. Emlet, Charles P. Hoy-Ellis, Jayn Goldsen, and Anna Muraco. 2014. Physical and mental health of Transgender older adults: An at-risk and underserved population. The Gerontologist 54: 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Acosta, Jesús Manuel, María Elisa de Castro Peraza, María de los Ángeles Arias-Rodríguez, Rosa Llabrés-Solé, Nieves Doria Lorenzo-Rocha, and Ana María Perdomo-Hernánde. 2019. Atención sanitaria trans* competente, situación actual y retos futuros. Revisión de la literatura [Competent trans health care, current situation and future challenges: A literature review]. Enfermería Global 18: 529–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Vega, Elena, Aida Camero, María Fernández, and Ana Villaverde. 2018. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in persons with gender dysphoria. Psicothema 30: 283–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Estigma. La identidad deteriorada [Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity]. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- González, Samantha, and Margarita Bernales. 2022. Chilean Trans men: Healthcare needs and experiences at the public health. International Journal of Mens Social and Community Health 5: e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Jaime M., Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jack Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling. 2011. Injustice at every turn: A report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Available online: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Grant, Jaime M., Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jody L. Herman, Jack Harrison, and Mara Keisling. 2010. National Transgender Discrimination Survey Report on Health and Health Care. Available online: https://cancer-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/National_Transgender_Discrimination_Survey_Report_on_health_and_health_care.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Hostetter, C. Riley, Jarrod Call, Donald R. Gerke, Brendon T. Holloway, N. Eugene Walls, and Jennifer C. Greenfield. 2022. “We are doing the absolute most that we can, and no one is listening”: Barriers and facilitators to health literacy within transgender and nonbinary communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyos, Paula, Carolina Duarte, and Laura Valderrama. 2023. Atención de los profesionales de la salud a personas trans en América Latina y el Caribe [Healthcare professionals’ attention to trans people in Latin America and the Caribbean]. Interdisciplinaria 40: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, Kimberly. 2018. (Un)doing transmisogynist stigma in health care settings: Experiences of ten transgender women of color. Journal of Progressive Human Services 30: 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Sandy E., Jody L. Herman, Susan Rankin, Mara Keisling, Lisa Mottet, and Ma’ayan Anafi. 2016. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. Available online: https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Johnson, Emilie K., and Courtney Finlayson. 2016. Preservation of fertility for gender and sex diverse individuals. Transgender Health 1: 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kcomt, Luisa, Kevin M. Gorey, Betty Jo Barrett, and Sean Esteban McCabe. 2020. Healthcare avoidance due to anticipated discrimination among transgender people: A call to create trans-affirmative environments. SSM—Population Health 11: 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, Evelyn Fox. 1985. Reflections on Gender and Science. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lerri, Maria Rita, Adriana Peterson Mariano Salata Romão, Manoel Antônio dos Santos, Alain Giami, Rui Alberto Ferriani, and Lúcia Alves da Silva Lara. 2017. Clinical Characteristics in a Sample of Transsexual People. RBGO Gynecology & Obstetrics 39: 545–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linker, Dania, Constanza Marambio, and Francesca Rosales. 2017. Encuesta T: Primera encuesta para personas trans y de género no-conforme de Chile [Survey T: First Survey of Trans and Non-Conforming Gender Persons in Chile]. Available online: https://otdchile.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Informe_ejecutivo_Encuesta-T.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Markovic, Lovro, Daragh T. McDermott, Sinisa Stefanac, Radhika Seiler-Ramadas, Darina Iabloncsik, Lee Smith, Lin Yang, Kathrin Kirchheiner, Richard Crevenna, and Igor Grabovac. 2021. Experiences and interactions with the healthcare system in transgender and non-binary patients in Austria: An exploratory cross-sectional study. International Journal Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, Ellen, Laurence Claes, Walter Pierre Bouman, Gemma L. Witcomb, and Jon Arcelus. 2016. Non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality in trans people: A systematic review of the literature. International Review of Psychiatry 28: 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Martínez, Jorge, Carlos Saus-Ortega, María Montserrat Sánchez-Lorente, Eva María Sosa-Palanca, Pedro García-Martínez, and María Isabel Mármol-López. 2021. Health inequities in LGBT people and nursing interventions to reduce them: A systematic review. International Journal Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 11801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltenburg, Solnes Andrea, Sandra van Pelt, Tarek Meguid, and Johanne Sundby. 2018. Disrespect and abuse in maternity care: Individual consequences of structural violence. Reproductive Health Matters 26: 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministerio de Salud Chile. 2023. Encuesta Nacional de Salud, Sexualidad y Género (ENSSEX 2022–2023). [National Survey of Health, Sexuality and Gender (ENSSEX 2022–2023]. Available online: http://epi.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Informe_Metodologico_ENSSEX_2023.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- MOVILH. 2018. Encuesta Identidad, Santiago [Identity Survey, Santiago]. Available online: http://www.movilh.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Encuesta_Identidad_-Movilh-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Namaste, Viviane. 2000. Invisible Lives: The Erasure of Transsexual and Transgendered People. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat, Tonia, Danielle German, and Deanna Kerrigan. 2013. Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science & Medicine 84: 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, Sari L., Seth T. Pardo, Kristi E. Gamarel, Jaclyn M. White Hughto, Dana J. Pardee, and Colton L. Keo-Meier. 2015. Substance use to cope with stigma in healthcare among US female-to-male trans masculine adults. LGBT Health 2: 324–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, Damien W., Katrina Coleman, and Clemence Due. 2014. Healthcare experiences of gender diverse Australians: A mixed-methods, self-report survey. BMC Public Health 14: 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risher, Kathryn, Darrin Adams, Bhekie Sithole, Sosthenes Ketende, Caitlin Kennedy, Zandile Mnisi, Xolile Mabusa, and Stefan D. Baral. 2013. Sexual stigma and discrimination as barriers to seeking appropriate healthcare among men who have sex with men in Swaziland. Journal of the International AIDS Society 16: 18715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Amanda, Anette Agardh, and Benedict O. Asamoah. 2018. Self-reported discrimination in health-care settings based on recognizability as transgender: A cross-sectional study among transgender U.S. citizens. Archives of Sexual Behavior 47: 973–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roselló-Peñaloza, Miguel. 2018. No Body: Clinical Constructions of Gender and Transsexuality—Pathologisation, Violence and Deconstruction. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rowlands, Sam, and Amy Jean-Jacques. 2018. Preserving the reproductive potential of transgender and intersex people. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care 23: 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seelman, Kristie L., Matthew J. P. Colón-Diaz, Rebecca H. LeCroix, Marik Xavier-Brier, and Leonardo Kattari. 2017. Transgender noninclusive healthcare and delaying care because of fear: Connections to general health and mental health among transgender adults. Transgender Health 2: 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shires, Deirdre A., Daphna Stroumsa, Kim D. Jaffee, and Michael R. Woodford. 2018. Primary care clinicians’ willingness to care for transgender patients. The Annals of Family Medicine 16: 555–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Adina J., Rachel Hallum-Montes, Kyndra Nevin, Roberta Zenker, Bree Sutherland, Shawn Reagor, M. Elizabeth Ortiz, Catherine Woods, Melissa Frost, Bryan Cochran, and et al. 2018. Determinants of transgender individuals’ well-being, mental health, and suicidality in a rural state. Rural Mental Health 4: 116–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subsecretaría de Salud Pública (11/11/2022). 2022. Reitera directrices para anticoncepción quirúrgica y consentimiento informado en regulación de la fertilidad [Restates Guidelines for Surgical Contraception and Informed Consent in Fertility Regulation]. Available online: https://diprece.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Circular-N°09-Esterilizacion-Quirurgica.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Truszczynski, Natalia, Anneliese Singh, and Nathn Hansen. 2020. The discrimination experiences and coping responses of Non-Binary and Trans People. Journal of Homosexuality 69: 741–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.N. Human Rights Council. 2013. Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Juan E. Méndez. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/A.HRC.22.53_English.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Vupputuri, Summa, Stacie L. Daugherty, Kalvin Yu, Alphonse J. Derus, Laura E. Vasquez, Ayanna Wells, Christine Truong, and E. W. Emanuel. 2021. A mixed methods study describing the quality of healthcare received by Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Patients at a Large Integrated Health System. Healthcare 9: 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, Sam, Milton Diamon, Jamison Green, Dan Karasic, Terry Reed, Stepheb Whittle, and Kevan Wylie. 2016. Transgender people: Health at the margins of society. Transgender Health 388: 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapata Pizarro, Antonio, Cristina Muena Bugueño, Susana Quiroz Nilo, Juan Alvarado Villarroel, Francisco Leppes Jenkis, Javier Villalón Friedrich, and Diego Pastén Ahumada. 2021. Percepción de la atención de salud de personas transgénero en profesionales médicos y médicas del norte de Chile [Perception of health care for transgender people among medical professionals of the north of Chile]. Revista Chilena de Obstetricia y Ginecología 86: 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata Pizarro, Antonio, Karina Díaz Díaz, Luis Barra Ahumada, Lorena Maureira Sales, Jeanette Linares Moreno, and Franco Zapata Pizarro. 2019. Atención de salud de personas transgéneros para médicos no especialistas en Chile [Heath care of transgender people for non-specialist doctors in Chile]. Revista Médica de Chile 147: 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwickl, Sav, Alex Wong, Ingrid Bretherton, Max Rainier, Daria Chetcuti, Jeffrey D. Zajac, and Ada S. Cheung. 2019. Health needs of trans and gender diverse adults in Australia: A qualitative analysis of a national community survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question: Have you had any of these experiences when seeking attention in the health system? You may tick more than one option. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Question: If you suffered one or more of the experiences mentioned previously, what did you do about it? You may tick more than one option. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Experiences of Abuse in Trans and Non-Binary Health Care | Total Sample (N = 778) | Male Gender (N = 320) | Female Gender (N = 129) | Non-Binary Gender (N = 266) | Fluid Gender (N = 43) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Inappropriate use of pronouns | 65.9 | 513 | 67.5 | 216 | 58.9 | 76 | 68.8 | 183 | 60.5 | 26 |

| Stereotypical comments about genders | 48.3 | 376 | 45.6 | 146 | 37.2 | 48 | 54.1 | 144 | 60.5 | 26 |

| Abrupt or reluctant attention | 44.0 | 342 | 43.4 | 139 | 39.5 | 51 | 45.5 | 121 | 44.2 | 19 |

| Signs of discomfort | 44.0 | 342 | 45.9 | 147 | 39.5 | 51 | 45.5 | 121 | 34.9 | 15 |

| Refusal to respect the person’s social name | 43.3 | 337 | 46.3 | 148 | 43.4 | 56 | 41.7 | 111 | 34.9 | 15 |

| Ignoring the person’s own knowledge of their body and gender identity | 35.2 | 274 | 33.1 | 106 | 24.0 | 31 | 39.8 | 106 | 44.2 | 19 |

| Sarcastic or ironic replies to the person’s questions | 35.2 | 274 | 33.8 | 108 | 27.9 | 36 | 39.5 | 105 | 37.2 | 16 |

| Omission or lack of information about medical procedures and their possible adverse effects | 29.4 | 229 | 30.9 | 99 | 27.9 | 36 | 27.1 | 72 | 32.6 | 14 |

| Derogatory comments about the person’s gender identity or expression | 28.9 | 225 | 26.9 | 86 | 23.3 | 30 | 33.1 | 88 | 32.6 | 14 |

| Inadequate or superficial care | 26.0 | 202 | 26.6 | 85 | 21.7 | 28 | 27.4 | 73 | 27.9 | 12 |

| Excessive requests for procedures or documents | 22.0 | 171 | 30.0 | 96 | 24.8 | 32 | 14.3 | 38 | 7.0 | 3 |

| Forced care, or care without consent | 16.5 | 128 | 18.4 | 59 | 18.6 | 24 | 12.0 | 32 | 23.3 | 10 |

| Attempts at dissuasion, or suggestions that gender transition processes be abandoned | 15.8 | 123 | 19.7 | 63 | 14.7 | 19 | 11.7 | 31 | 14.0 | 6 |

| Refusal of services | 15.3 | 119 | 18.1 | 58 | 21.7 | 28 | 10.5 | 28 | 7 | 3 |

| Sexual aggression | 7.8 | 61 | 5.6 | 18 | 7.8 | 10 | 9.8 | 26 | 11.6 | 5 |

| Physical assault on receiving attention | 4.0 | 31 | 3.4 | 11 | 4.7 | 6 | 4.1 | 11 | 4.7 | 2 |

| Sterilization without consent | 1.9 | 15 | 2.5 | 8 | 2.3 | 3 | 1.1 | 3 | 0.0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roselló-Peñaloza, M.; Julio, L.; Álvarez-Aguado, I.; Farhang, M. Abuse in Chilean Trans and Non-Binary Health Care: Results from a Nationwide Survey. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040228

Roselló-Peñaloza M, Julio L, Álvarez-Aguado I, Farhang M. Abuse in Chilean Trans and Non-Binary Health Care: Results from a Nationwide Survey. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(4):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040228

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoselló-Peñaloza, Miguel, Lukas Julio, Izaskun Álvarez-Aguado, and Maryam Farhang. 2024. "Abuse in Chilean Trans and Non-Binary Health Care: Results from a Nationwide Survey" Social Sciences 13, no. 4: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040228

APA StyleRoselló-Peñaloza, M., Julio, L., Álvarez-Aguado, I., & Farhang, M. (2024). Abuse in Chilean Trans and Non-Binary Health Care: Results from a Nationwide Survey. Social Sciences, 13(4), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040228