Abstract

The question of gender equality is increasingly being raised today and is present at all levels of society. The topicality of the issue on farms is particularly evident, due to the particular inheritance processes on farms, the clear division of labour, and intergenerational cooperation that characterise the agricultural sector. In this research, a multi-criteria model (DEX-SOCIAL) was developed to understand the broader aspect of rural sociology and the issue of women’s status on the farm. The paper discusses the status of women on a farm and assesses their social and economic situation. The methodology includes an online questionnaire in which women in the Eastern and Western Cohesion Regions participated, as well as other farm members and owners. Subsequently, the questions were transformed for the requirements of the assessment model, which assessed the life prospects of women on farms in both the Eastern and Western Cohesion Regions who were aged both over and under 40 years (criteria for “young successor”). The results of the study show that there is a clear difference in the qualitative assessment of women’s socio-economic position in relation to the East–West cohesion region. The social position of women does not differ according to age structure. The conclusions of the study also present broader applications of the results in the field of rural development and rural sociology.

1. Introduction

Women in rural areas of the EU make up below 50% of the total rural population, they represent 45% of the economically active population, and about 40% of them work on family farms. Their importance in rural economy is even greater, since their participation, through informal rural economy, is not statistically recognized (Franić and Kovačićek 2019). According to the Ministry of Labour, Family, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities, summarised according to data from the Statistical Office, in 2016, there were 10,762 female farm owners in Eastern Slovenia, with an average age of 58 years, and in Western Slovenia there were 3334 women, with an average age of 61 years. In 2016, 48,889 women in the eastern region, with an average age of 49, and 21,099 women in the western cohesion region, with an average age of 50, were listed as other family members (SI-STAT 2016). The Eastern cohesion region comprises Southeast Slovenia, Koroška, Podravska, Pomurska, Posavska, Savinjska, Zasavska, and the Primorsko-Notranjska region. The Western cohesion region comprises Gorenjska, Goriška, Osrednjeslovenska, and the Obalno-kraška region. Great progress towards work and quality of life on the farm is reflected in training, as well as school, vocational, and academic education (Rossi 2022). With their education, professionalism, and skills, women strive to further develop traditional rural living and economic structures. They participate in the stabilisation and modernisation of rural forms of farming. At the same time, they contribute to market adaptation and diversification of the economy. Farms are an important factor in supplying rural areas; in addition to food production, they also offer innovative products and services. Women farmers must be given tasks and rights in the interest of their co-responsibility in agriculture. Representation in agricultural cooperatives, participation in agricultural income, as well as social insurance for all women working in agriculture is necessary (according to Muršec 2018).

According to one study (Robnik 2018), most of the respondents said that being a farmer’s wife is a great advantage, because they can work freely, manage their own time, and enjoy working on the farm. As regards the disadvantages of being a farmer’s wife, the respondents in the survey most often mentioned reasons such as the work on the farm is exhausting, they are overworked, they have a subordinate position, and they are economically dependent. From the above statements, we can summarize that there are both social and economic factors that affect the status of women on farms.

Women in Slovenia, as in all EU countries, have the same rights as men. It should be emphasised that rural women and women living on farms do not necessarily belong to the same group. The difference is not only in lifestyle and the production of agricultural products, but also in the participation in public and political affairs. In the literature, the term “farmer’s wife” is used for a woman who works in agricultural production or is supported by a person working in agricultural production. The term “rural woman” is used to refer to all women, regardless of their education and social status (Pajnik 2000). One of the greatest desires of rural women is to receive greater recognition and economic appreciation for their work, which would give them greater personal satisfaction and economic independence, as well as the right to social security. If all this were available to them, it would mean not only their own satisfaction, but also that of rural families and, thus, a better future for the countryside (Pajnik 2000).

In the individual chapters, after an initial review of the professional, scientific, domestic, and foreign literature, the peasant woman is introduced. The dissemination and inclusion of the fact that there is a Western and an Eastern Slovenian region is also important, as the eastern part of Slovenia has the conditions for predominantly intensive agriculture and the western part of Slovenia has the conditions for predominantly extensive agriculture. Therefore, we will make a comparison between the Eastern and Western Cohesion Regions and between women under and over 40 years of age—one of the criteria for being a young successor. The definition for young successor describes the natural or legal person who is the manager of the holding, which means that he/she is the owner of the holding and exercises effective and long-term control over the holding, i.e., makes decisions regarding management, benefits, and financial risks and is responsible for the implementation of agricultural activities on the holding. He is not older than 40 years and has the required knowledge and skills. At least three years of professional experience on the farm are deemed to be the knowledge and skills required to carry out agricultural activities (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food 2022).

A multi-criteria method (DEX) was used to investigate the survey study. This is a specific methodology for which a computer-based support tool, DEXi, has already been successfully used (Bohanec 2017) in numerous real-life decision-making and evaluation problems (Vindiš et al. 2012; Rosario et al. 2021; Puška et al. 2022), as well as in the field of rural sociology (Borec et al. 2013). The methodology is useful because this study collected mainly qualitative data (questionnaires). Some data that had numerical values were categorised into the corresponding qualitative class by forming descriptive groups (Trdin and Bohanec 2018). The programme was developed by the Josef Stefan Institute in Slovenia and it is freely available on the internet.

The added value and originality of the contribution can be seen in the comprehensive assessment of the position of women on farms. So far, specific segments or specific objectives (such as succession, educational structure, and farm income) have been assessed, but not satisfaction with life in the countryside as a whole. We assume that, with the results of this paper, we will make a good contribution to a better understanding and assessment of the current state of the socio-economic situation of women on farms in Slovenia and, at the same time, identify those factors that are important for the improvement of the discussed topic. The aim of this study is to assess the socio-economic status of women in Slovenia and, further, the hypothesis can be formulated whereby we assess the social and economic status of women according to assessment groups (according to ages and location of farm).

This paper is structured into a standard format with a methodology description, a results and discussion section, and a conclusion section. At the end, the authors explain the study limitations and the future challenges for using and upgrading the developed model for solving related rural sociology issues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Input Data

The data were collected using a questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 25 open and closed questions (23 of them were closed and 2 were open). The questionnaire was divided into two sections. One concerns the social status and the other concerns the economic status of women on farms. The questions in the social section refer to social characteristics and family characteristics. The questions in the economic situation refer to the income situation and the description of the farm. The questionnaire was developed into an online version and 127 women from farms in the Eastern and Western Cohesion Regions participated in the research. With the questionnaire, which we sent out to various target groups, we wanted to obtain as many responses as possible and, thus, form as large a sample as possible for the analysis. On the basis of the completed questionnaires received (127), we formed four different groups within the sample (referred to as variants in the model), depending on the cohesion region from which the respondents came and their age. In total, 103 questionnaires were used, the rest were incorrectly completed and were, therefore, unusable. The questionnaire was conducted between February and April 2022 and was distributed to various associations of women farmers in Slovenia, as well as to the Association of Slovenian Rural Youth and also to agricultural and forestry institutes. Participation in the questionnaire was voluntary and anonymous. We defined the possible answers to questions for closed question types by dividing them numerically, according to the measurement scale we set for each criterion in the model. We processed the data in MS Office Excel, where we calculated the numerical mean. This value was then transferred into a qualitative form in the model.

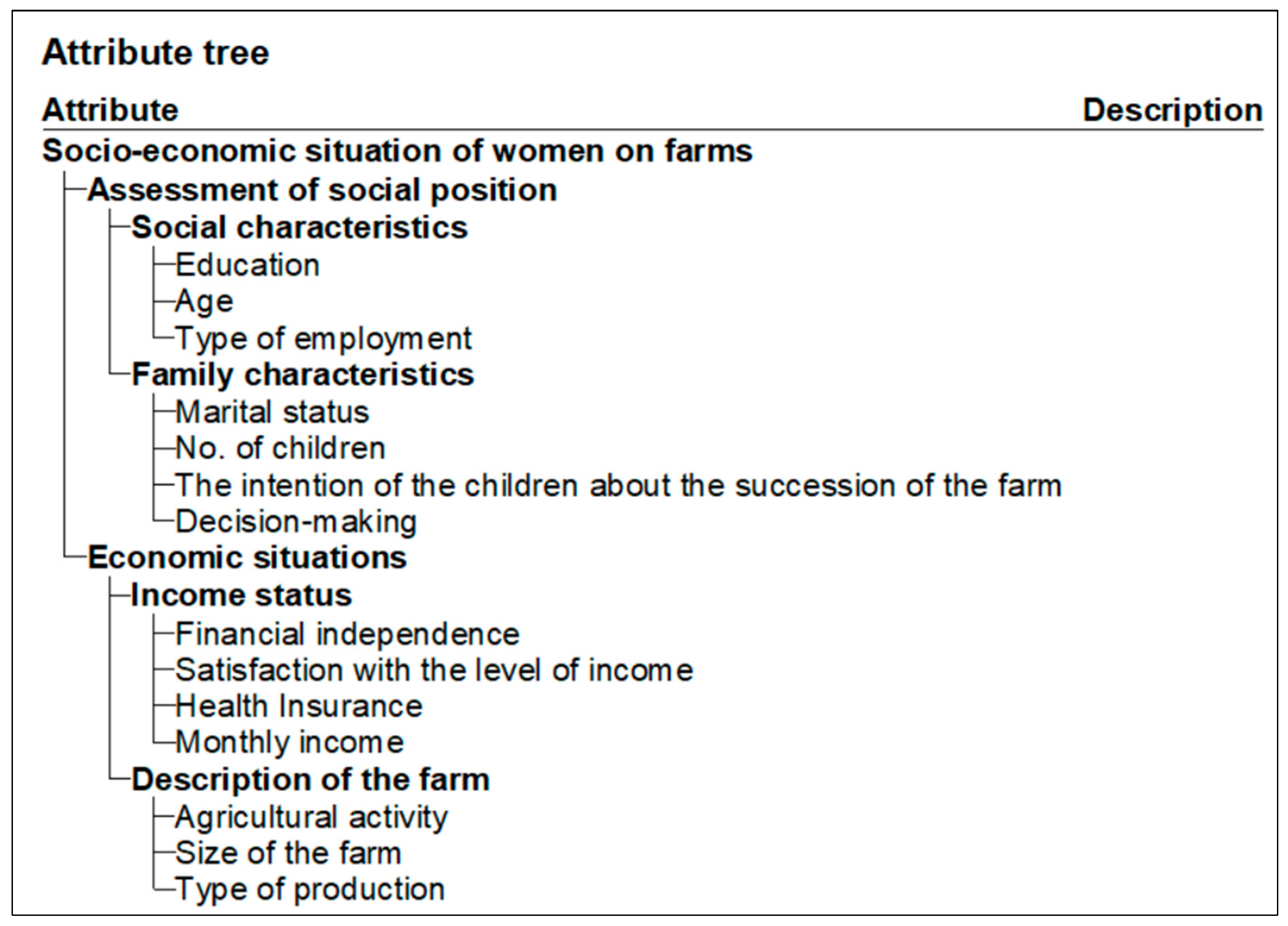

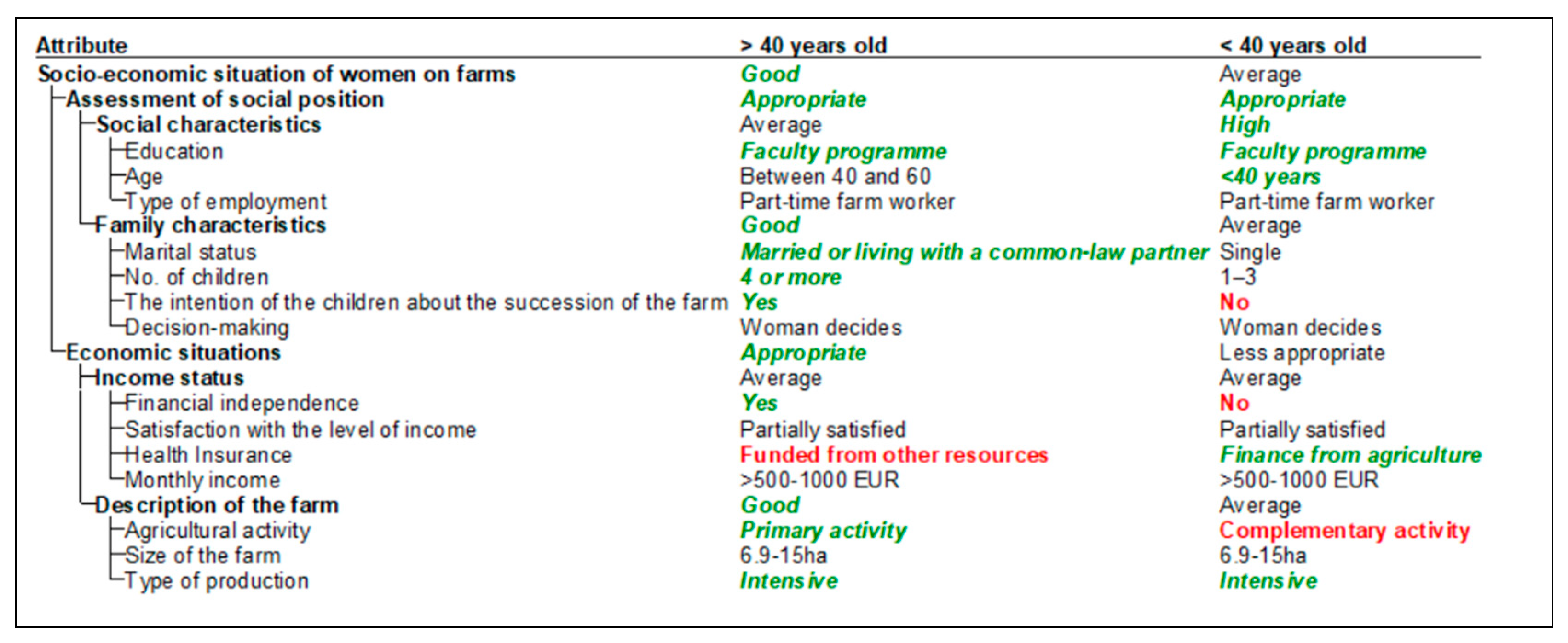

The questionnaire was created in parallel with the creation of the model (Figure 1). It was important to include as many questions as possible that clearly assessed the social and economic position of women on farms. The answers to the questions represented the attributes in the model, which were ranked according to their relevance to the social or economic assessment.

Figure 1.

Attribute tree of DEX-SOCIAL model—original model printout.

The resulting data served as a guide for assessing the importance of the criteria and for creating utility functions.

The first level was divided into basic criteria, as follows: Assessment of women’s social status and economic position. All criteria of the first level are subdivided into criteria of the second level, whereby the criterion assessment of women’s social position is subdivided into the following: social characteristics and family characteristics, while the criterion of economic position is subdivided into income situation and description of the farm. The second level criteria are subdivided into the third level, whereby the social characteristics’ criterion is subdivided into education and type of employment, while the family characteristics’ criterion is subdivided into marital status, number of children, children’s intention regarding farm succession, and decision-making. The criterion of income circumstances is subdivided into financial independence, satisfaction with the level of income, health insurance, and monthly income. The criteria describing the farm include farming activity, farm size, production method, and agricultural sector.

2.2. Model Development

2.2.1. Theory of the Development of DEX Models

The originality of this study is also evident in the use of multi-criteria analysis, which is normally used to support decision-making, but in this case (as in some earlier ones) was used as an evaluation tool. However, the modelling procedures are the same and are described below (according to Bohanec 2017).

Identification of the problem. In this phase, the problem is defined, the goals and requirements are processed. We also form a decision-making group (or assessment groups), the core of which are the owners of the problem and the working method (how we will approach the problem and what tools we will use).

Identification of alternatives. It is necessary to find out which alternatives we can choose, but we usually want to know and define as many alternatives as possible, as this increases the possibility of making the right decision.

Identifying the criteria. We identify the criteria and design the structure of the decision model. In doing so, we adhere to the principle of completeness. When designing the model, we must not neglect other requirements—structuredness, non-redundancy, orthogonality, and operational criteria. Therefore, we carry out this phase in the following steps: criteria list (listing of all criteria), structuring of criteria (hierarchical arrangement of criteria, the result is a criteria tree), and measurement scales (determination of the set of values).

Determination of preferences or utility functions. Functions are defined that define the influence of the lower-level criteria on the higher-level criteria, up to the root of the tree, which represents the final variant evaluation. In our case, we used the weighted sum function and various average value.

Description of variants. Each variant is described with the values of the basic criteria (which are on the leaves of the tree). Studying the variants and collecting data about them leads us to the description.

Evaluation and analysis of variants. Variant evaluation is the process of determining the final score of variants based on their description, using criteria. The evaluation is carried out from the bottom up, according to the structure of the criteria and utility functions. The variant with the highest score is generally the best.

Analysis and interpretation of the results. This is important because the evaluation of the alternative alone is often not sufficient to obtain a comprehensive picture of the individual alternative.

Conclusion and implementation of the decision. We identify the final outcome of the decision, select the best alternative, and describe its critical features to be considered in the implementation of the alternative. We indicate possible instructions for the implementation of the final decision. This phase is irreversible.

2.2.2. Practical Approach

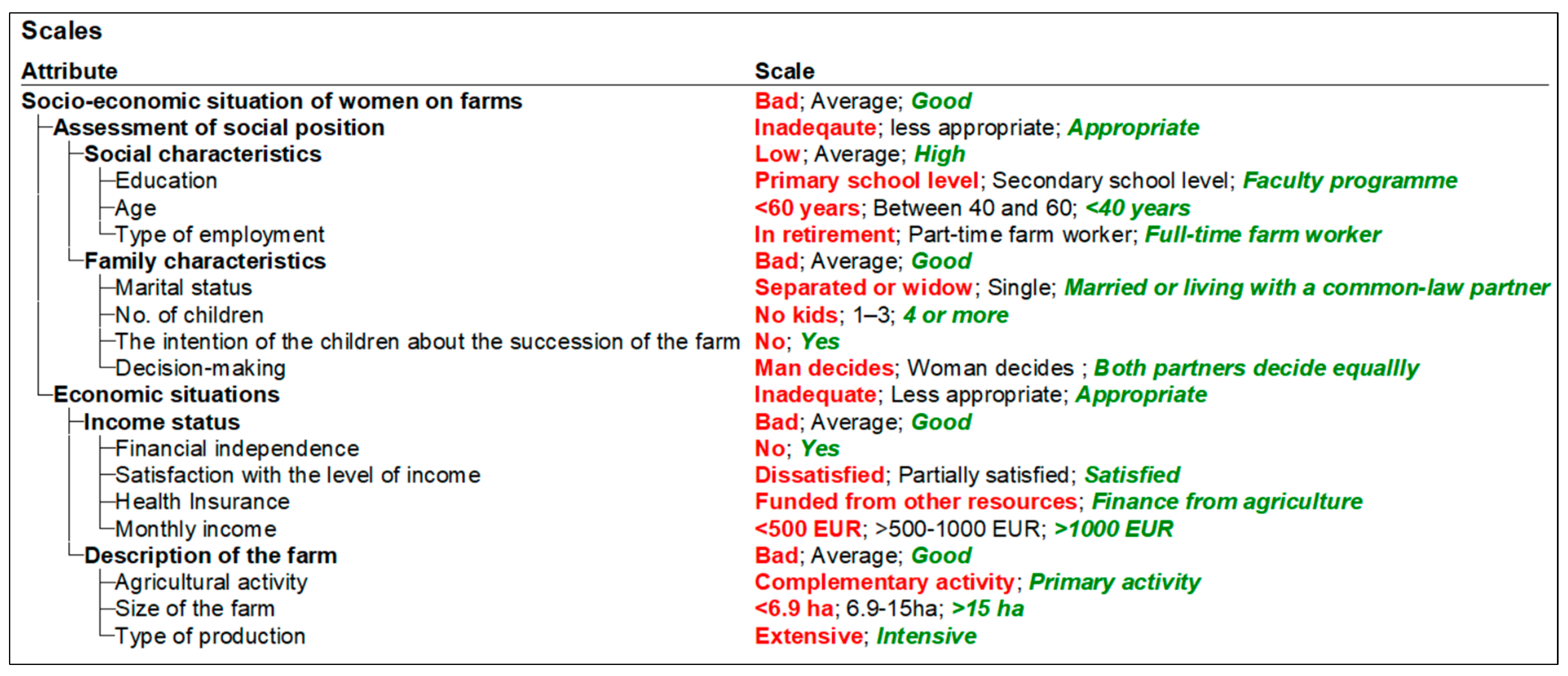

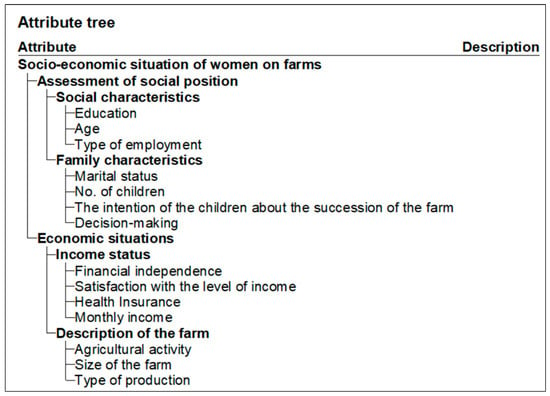

For each basic and derived criterion, we have established a scale of measurement with the help of a catalogue of values. It can be unordered or ordered, in the latter case ascending or descending. In our case, the scales are arranged in ascending order (from worst to best option) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Attribute scales—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

The determination of the numerical scales was mainly based on statistical characteristics from Slovenia (Table 1). In order to determine which farms are good or bad, in terms of size, we determined the numerical scale based on the average farm size, which, in Slovenia, is 6.9 hectares (ha). We divided the farms into the following classes: up to 6.9 ha, 6.9–15 ha, and over 15 ha. Taking into account the results of the questionnaire, the following measurement scale was created: small farms have up to 6.9 ha, medium farms have 6.9–15 ha, and large farms have over 15 ha. The best value was assigned to a large farm, a medium value to a medium farm, and the worst value to a small farm. The same applies to the criteria number of children and monthly income. Based on findings from statistical data and the literature, numerical and discrete intervals of possible values were formed for each criterion and then qualitative value inventories were created for them (as in Table 1). Following the same procedure, numerical scales were constructed for the other criteria (education, type of employment, marital status, number of children, children’s intention to inherit the farm, financial independence, satisfaction with the level of income, health insurance, monthly income, farming activity, production size, and type of production).

Table 1.

Examples of the determination of some numerical and qualitative values for individual attributes.

Table 2 shows the mean values of the attributes according to the individual evaluated variables that were included in the model. For attributes where the value set had two descriptive classes, the numerical scale ranged from 0 to 1 and 1 to 2. For attributes where three qualitative scales were defined, the mean values were distributed between 0–1, 1–2, and 2–3.

Table 2.

Mean values of the variables introduced into the model.

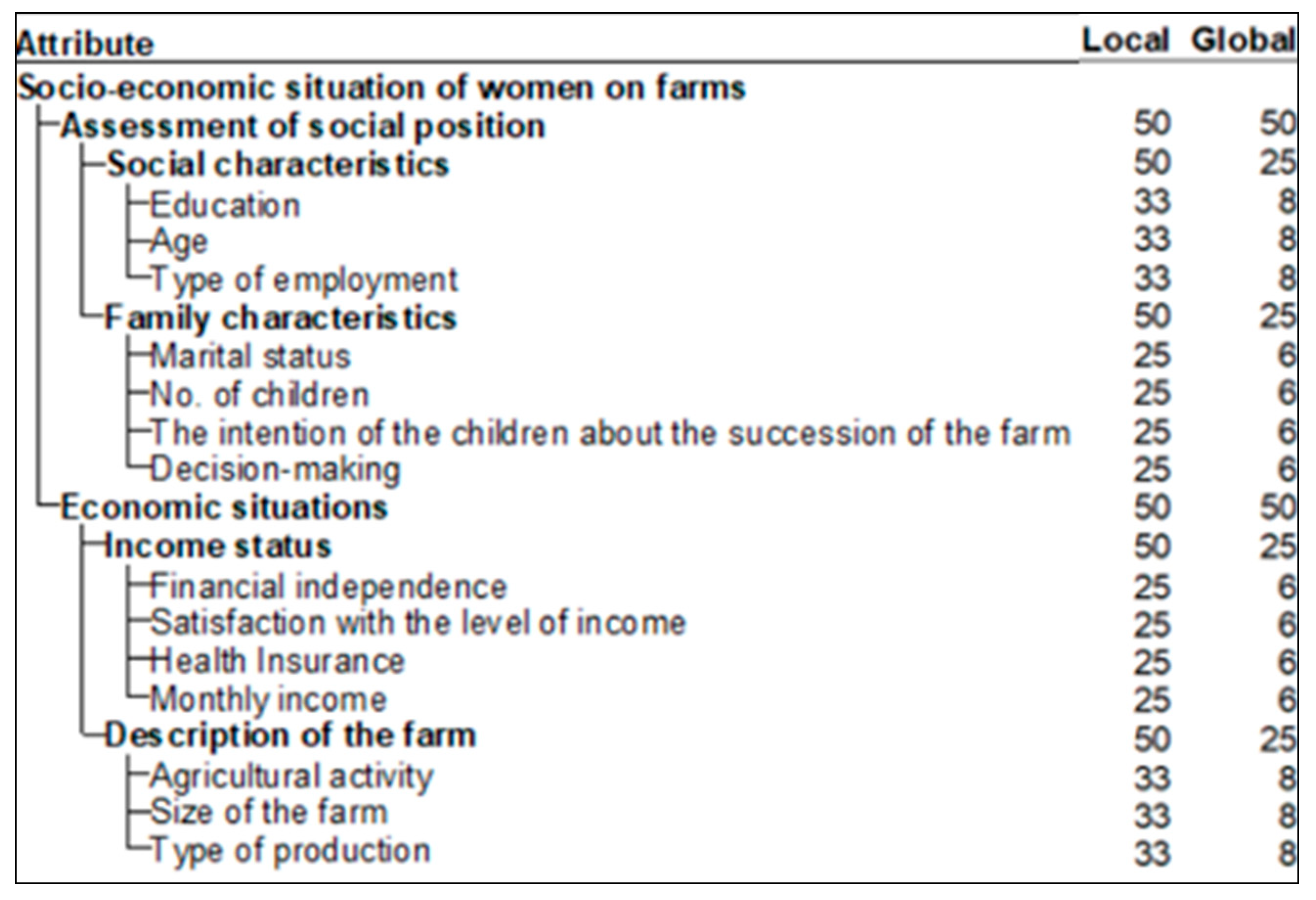

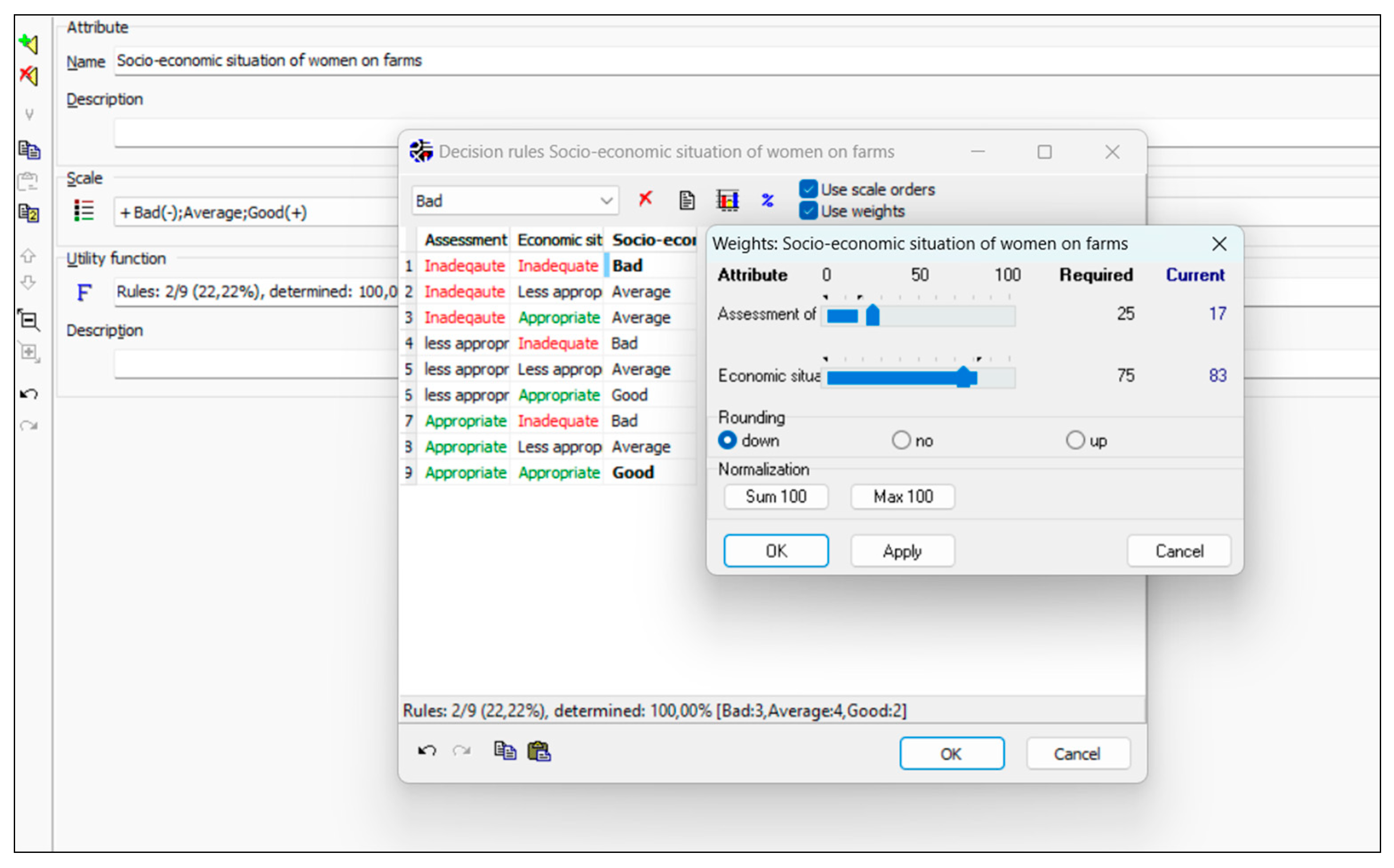

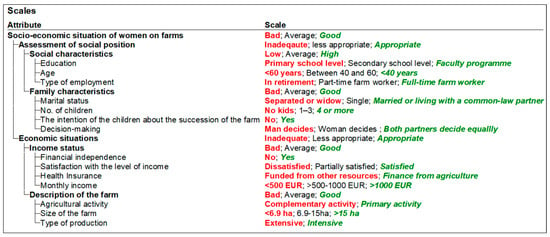

The next step was to define the utility functions. Utility functions are “what-if” decision rules that link lower-level criteria to higher-level criteria. In this way, the first level is defined to the second level and the second level to the third level. All three are combined into a final criteria-aggregated attribute and, ultimately, represent an evaluation of alternatives (aggregated decision rules). At the top of the hierarchy is a single attribute that represents the final evaluation of alternatives. Due to this stepwise integration of criteria, a utility function must be defined for all combinations of derived criteria, including the main criterion. The model presented contains a total of seven utility functions. We have assumed that the subordinate attributes have the same influence on each combined attribute (Figure 3). Otherwise, we would have to create an additional questionnaire defining the importance of each attribute for the respondents. This could be another challenge for the research question in the future. Figure 3 shows the average attribute weights at a local (in %) and global level (in a numerical scale). The weights were determinate as “equally” important attributes on the lower level to attribute on the aggregate level.

Figure 3.

Attribute weights on local and global level—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

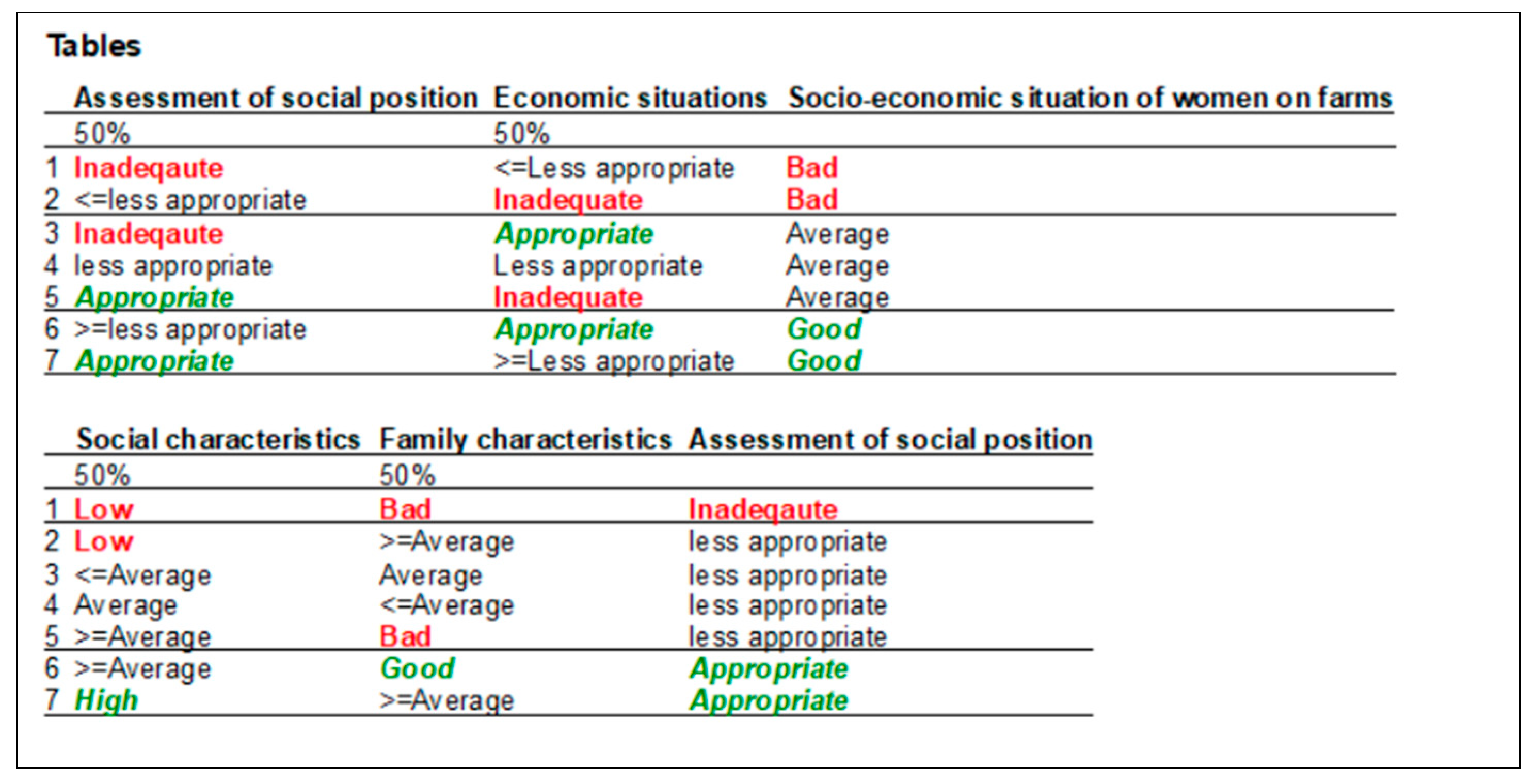

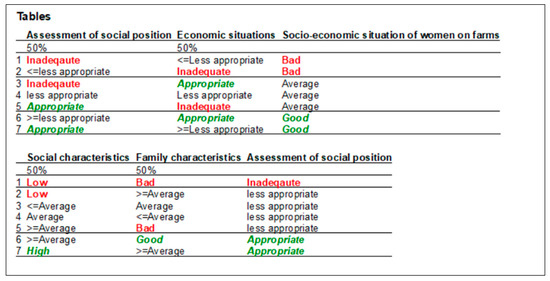

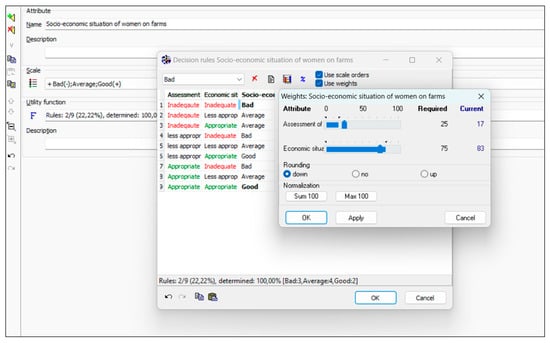

Rule 2 (the second table on Figure 4), for example, prescribes that the valuation of the social position of women farmers with “low” social characteristics and “average” family characteristics is classified as “less appropriate”. Decision rules can be presented in a combined form. The symbol <= means “equal or worse” and the symbol >= means “equal or better”. Rule 4, for example, states that a woman’s social status is classified as “less appropriate” if her social characteristics are classified as “high” and her family characteristics as “average or better” The upper part of the table in Figure 4 shows the weights based on the linear regression method with the rules of the DEXI programme (Bohanec 2008).

Figure 4.

Example of some part of model utility functions—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

3. Results

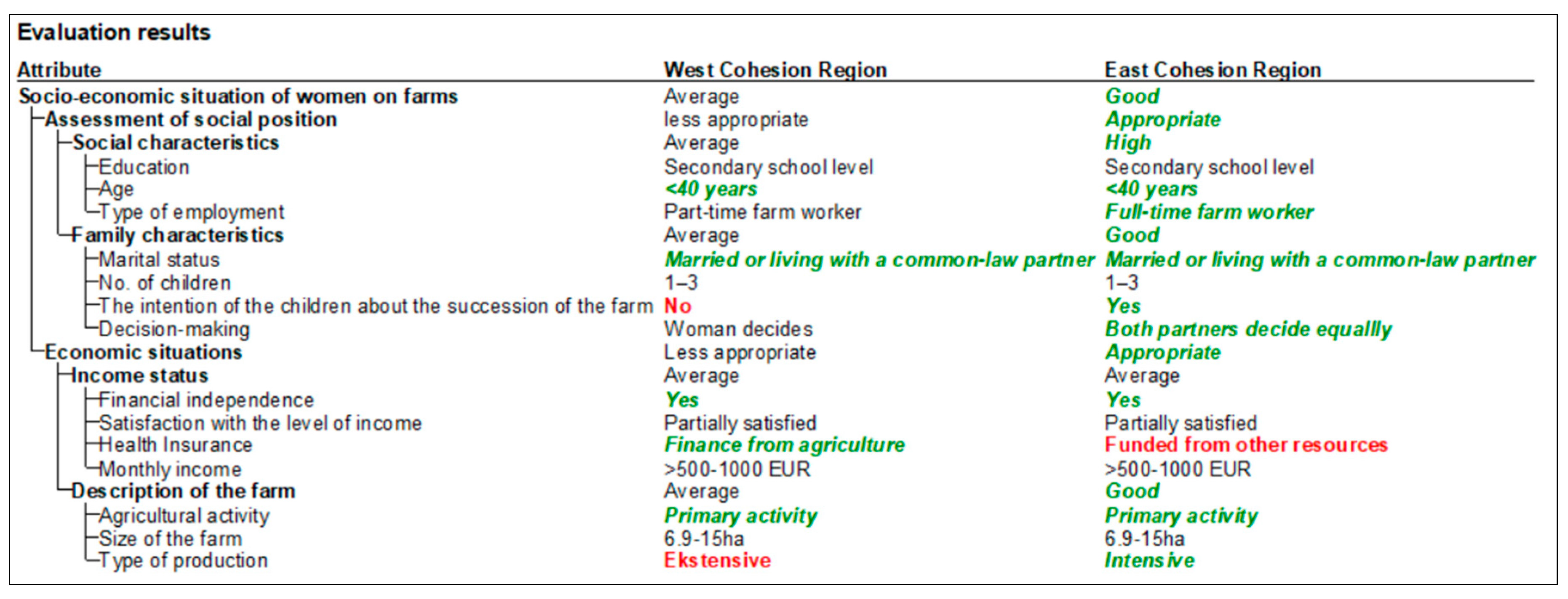

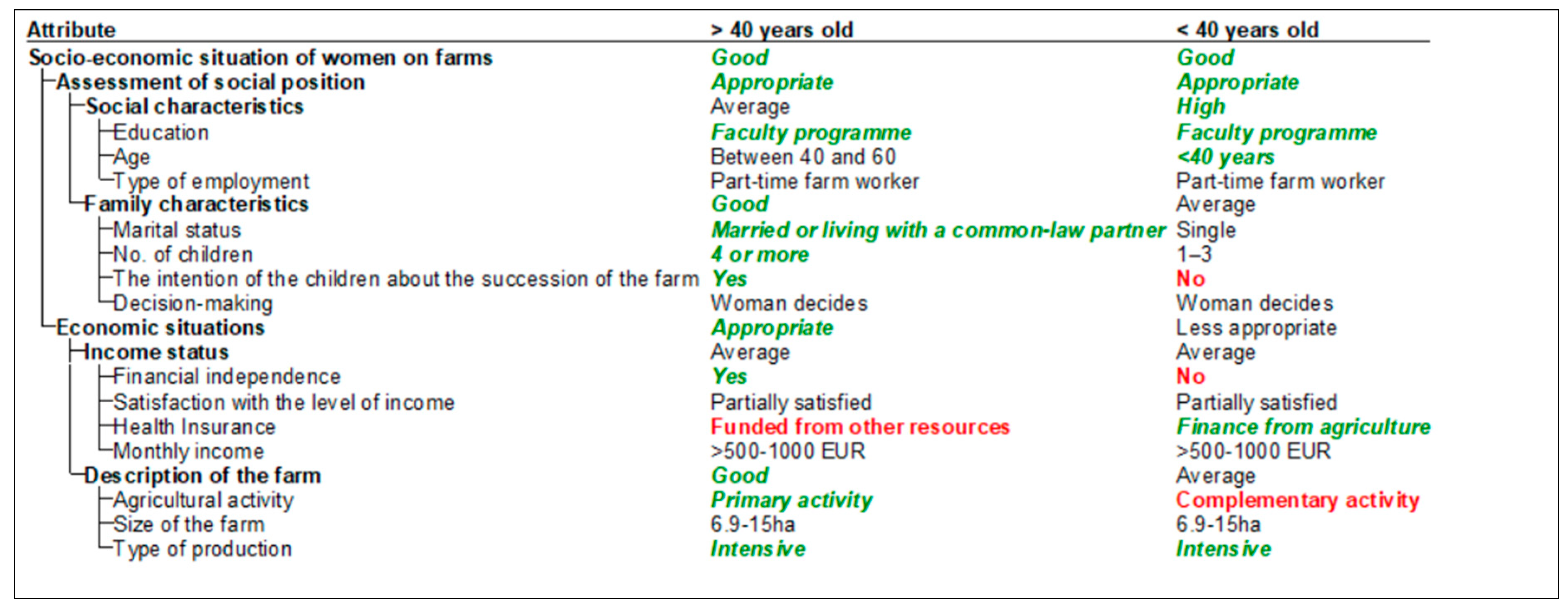

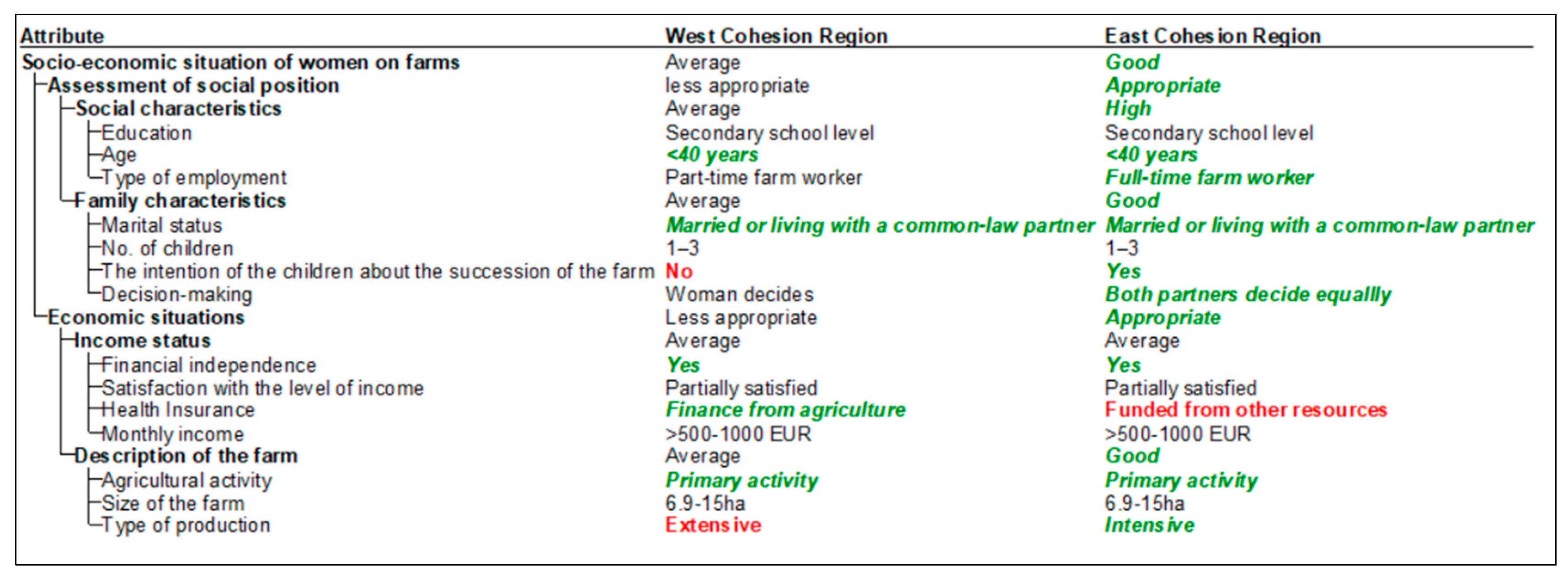

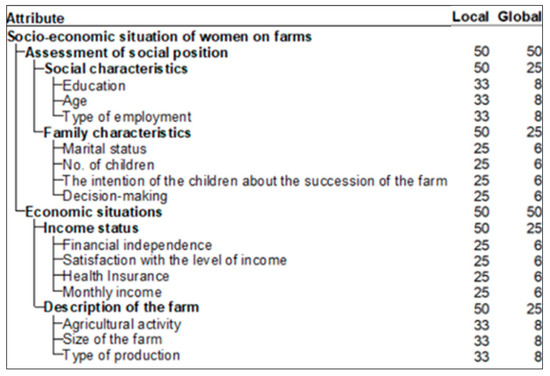

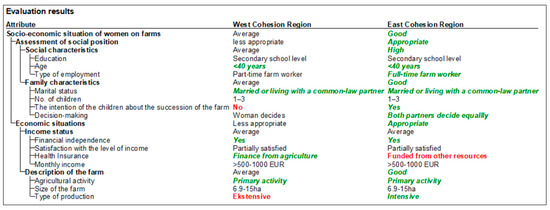

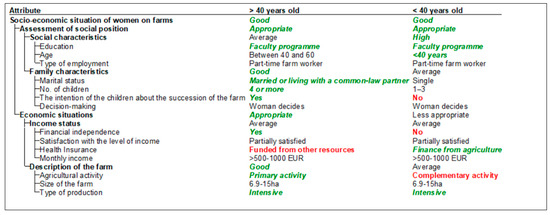

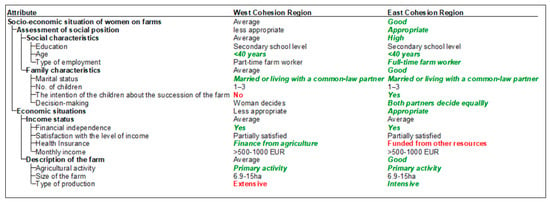

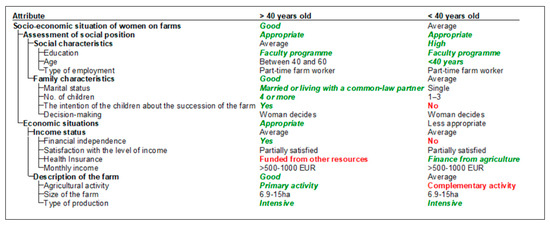

In the following section, we present the results of four variants of the DEX-SOCIAL model, which was developed to express the assessment of the social and economic situation of women on farms. The first two variants are divided according to the eastern and western cohesion regions of Slovenia. In addition, two variants are presented to assess the situation of women in the age groups below and above 40 years. All variants except one (the Western Cohesion Region) were rated “good”, while the aforementioned variant received the neutral rating “average” (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Evaluation results—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

Figure 6.

Evaluation results—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

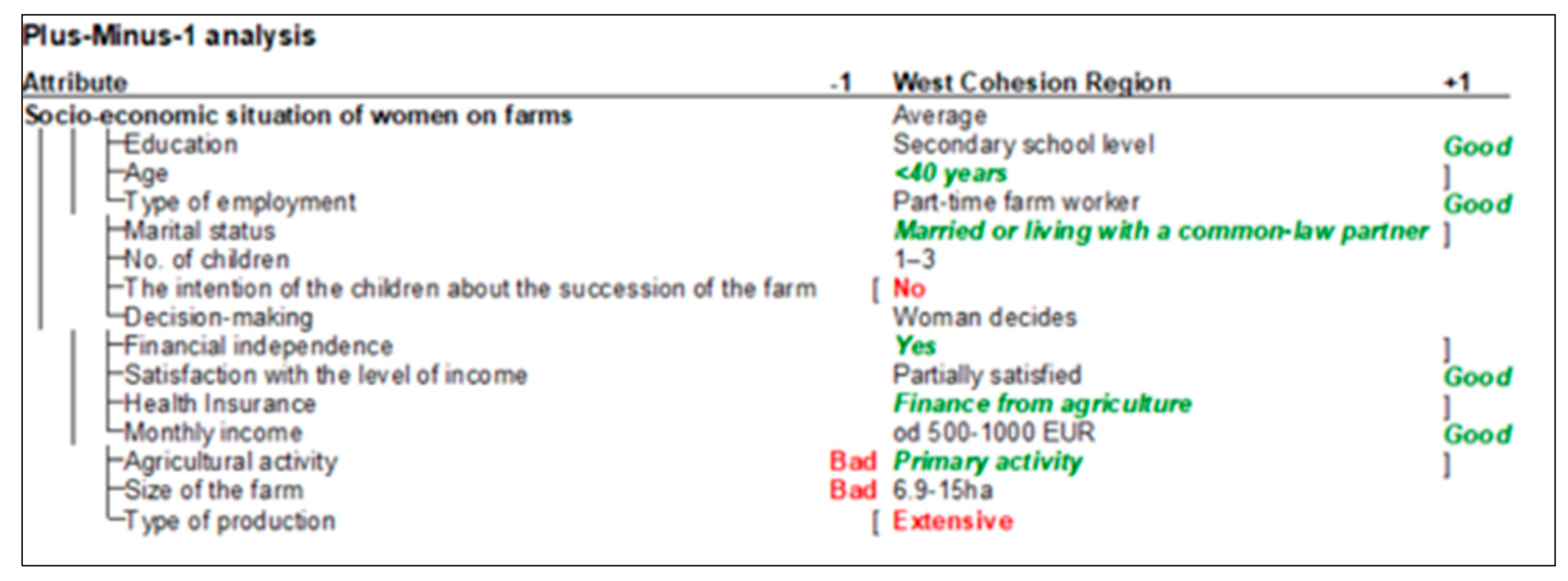

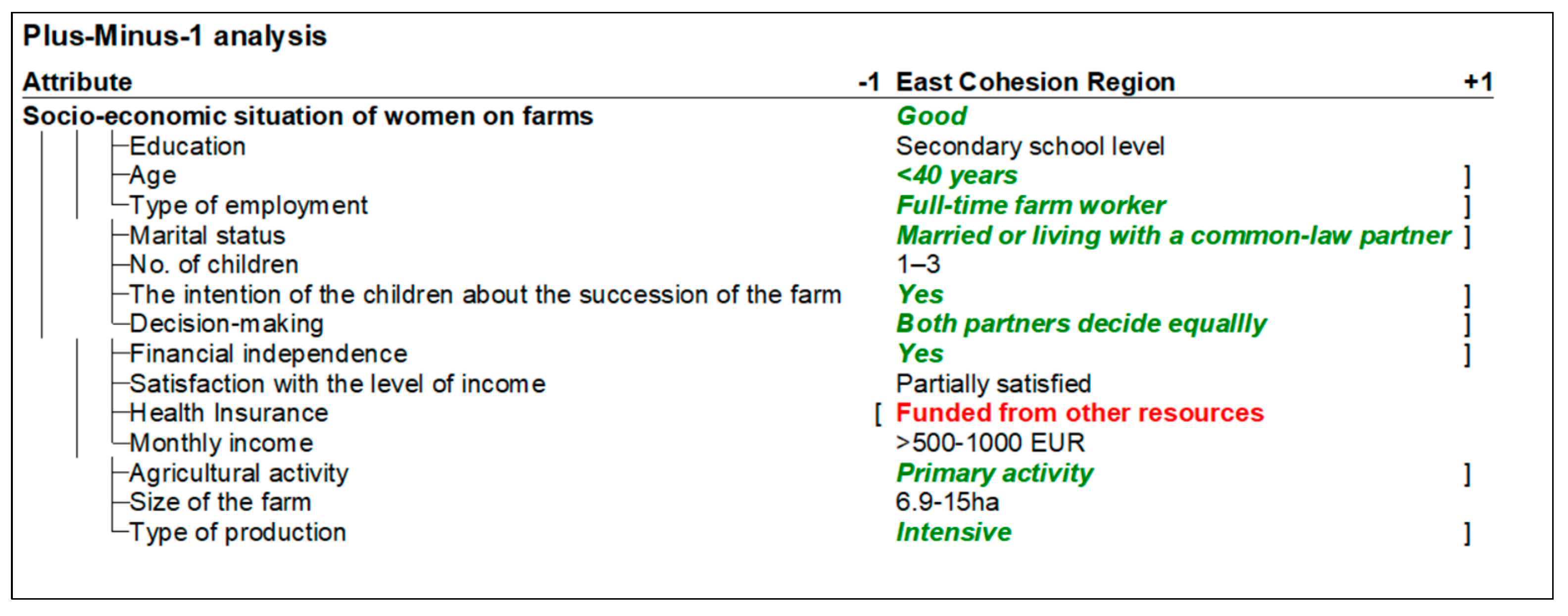

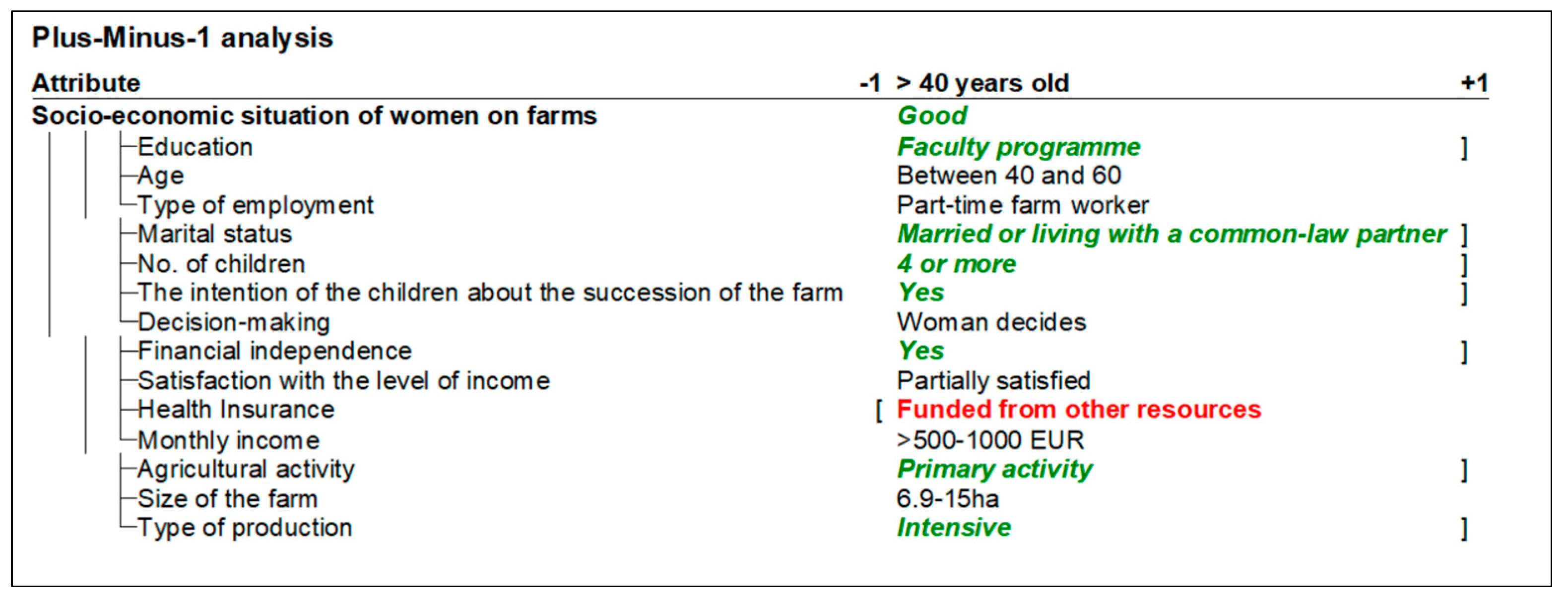

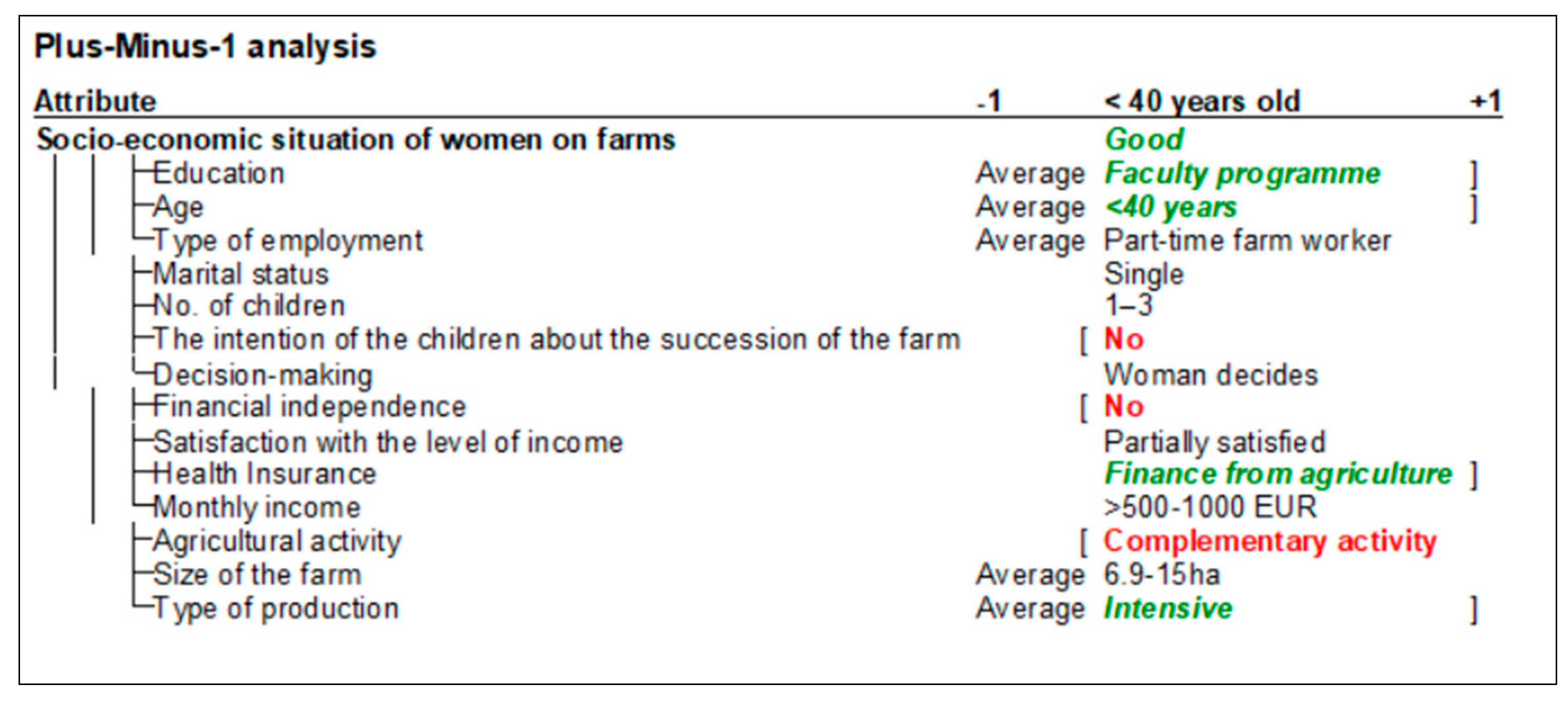

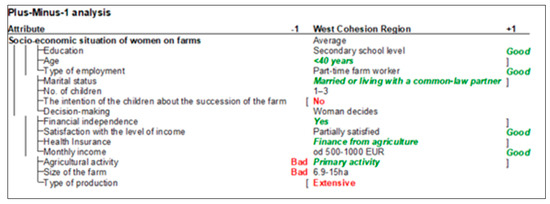

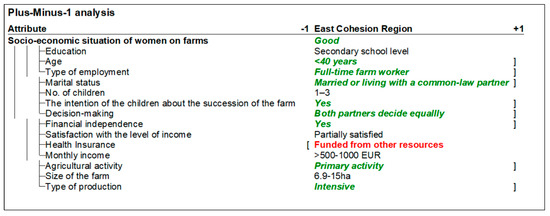

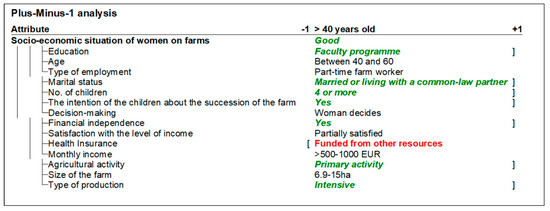

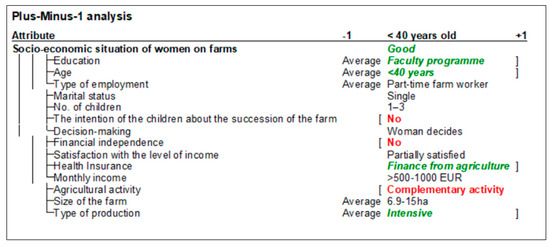

In the analysis of such models, it is not the final score that would explain the maximum statement of the model, but the analysis of the model is a way to improve the final score and identify negative or positive reasons for the assigned score. In the DEX-I methodology, this can be conducted with the “plus-minus-1 analysis”. This analysis asks how the final grade of the variant would change if the grade of one of the criteria changed, independently of the others. This type of analysis has often been used to reveal weaknesses in the structure of entire models. The plus-minus-1 analyses for all variants assessed are shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 7.

Results of plus-minus-1 analysis of variant “West Cohesion Region”—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

Figure 8.

Results of plus-minus-1 analysis of variant “East Cohesion Region”—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

Figure 9.

Results of plus-minus-1 analysis of variant “over 40”—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

Figure 10.

Results of plus-minus-1 analysis of variant “under 40”—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

The results of Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 show interesting results regarding the potential for improvement and also the impact of the current socio-economic status of women on family farms. Of concern is the fact that two criteria have been set for the “West Cohesion Region” variant that could lower the final score to the worst level. It is, therefore, important that these two criteria are particularly emphasised and explained. The size of family farms in the West Cohesion Region must not be reduced, as this could worsen their socio-economic situation, which would mean that agricultural activity would no longer play the main role for them.

4. Discussion

A discussion of the model results is particularly useful for all the variants, as hazards are identified here that can improve or worsen the final evaluation of the variants. The identification of the criterion “decision-making”, which occurs in two variants (Figure 8 and Figure 9), and can influence the final evaluation of the variants, is interesting (as was described in Chayal et al. 2013). For this criterion, it was taken into account that the best evaluation is the one in which both genders decide equally on the affairs of the farm (gender equality).

The number of children on the farm is the next accepted criterion that can influence the final score of the variants. In some previous studies (Dudek 2016; Casel and Pettersson 2015; Cavicchioli et al. 2015), the authors directly and indirectly address the issue of farm succession by making it dependent on the number of children, education, and interest in taking over the farm. The logic in such cases is simple—as the number of children on the farm increases, the higher the likelihood of a successful farm takeover and, thus, the higher the satisfaction of the current farm owners and an increased improvement in the economic situation on the farm.

According to the results of the plus-minus-1 analysis for the “under 40” variant, some statistical criteria were identified that jeopardise the highest rating of the variant. From the results, it can be concluded that the social and economic situation of women in the under 40 age group is quite good throughout Slovenia (regardless of the region to which the farm belongs). Undoubtedly, the financial incentives of the Rural Development Programme (RDP) aimed at young people also contribute to this and facilitate the start and continuation of agricultural activity. The Slovenian RDPs of 2004–2006 and 2007–2013 included two measures that facilitate the succession of farms to the next generation. These measures were meant to support agricultural development and farm modernisation, but also included specific support for female successors (Shortall and Bock 2015). Although the model developed is not intended to assess farm succession, it can, nevertheless, be summarised from the results of the model that it is important for the successful continuation of a career on the farm, and, thus, for the favourable social and economic position of women on farms, that they are in a partnership relationship in one of the bonding forms, that they have larger families, and that they consider farming activity as primary.

Considering that the ratings of the economic situation criteria were average in all versions, the final ratings in three positive cases can rightly be questioned as to the appropriate assignment of meanings to the individual criteria in the model. In terms of content, it becomes clear that the provision of an adequately paid job on farms is a prerequisite for economic independence. Therefore, it makes sense that the importance of the criterion economic situation is rated somewhat higher than the social situation of women on farms (Figure 11). The newly assigned weights were, thus, in the ratio of “social situation” ¼ and “economic situation” ¾.

Figure 11.

“New” weighting values of the criterion of social and economic situation—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

Such interventions in models are called “sensitivity tests” or response tests. This approach allows us to analyse the final assessments, which may vary according to the decision-maker’s opinion, depending on practical experience. In the following, the results of the model after changing the weight percentage of the criteria “social situation” and “economic situation” are presented (Figure 12 and Figure 13). Figure 13 shows that the final score was changed to the mean score “average” in case “<40 years old”.

Figure 12.

The results of the “sensitivity test” of the DEX-SOCIAL model—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

Figure 13.

The results of the “sensitivity test” of the DEX-SOCIAL model—original model printout. (The colored text helps the reader to distinguish between negative, neutral and positive values).

It is also interesting and important to note that there were differences between the regions (east and west). This can also be attributed to the type of cultivation, which, in the majority of the samples studied, is described as “intensive” in the east, but “extensive” in the west of the country. This is favoured by the natural conditions and the geographically more favourable location of the eastern cultivation area (in the plains). This makes it easier and faster to achieve a better economic situation for women on farms. This was also shown by the evaluation of the developed model. Summarising the discussion as a whole, it can be seen that it is a mature evaluation model that takes into account various transitions of criteria that finally come together to form a whole (final evaluation of the position of women on the farm).

The results also show a disparity between the development opportunities for agriculture in the western and eastern parts of the country. It is, therefore, important that this issue is also brought to the attention of policy makers, who can use the results of such a study to better understand the importance of balanced development of the areas and the preservation of family farms. Considering that the western part of the country is largely mountainous, it is important that the various development programmes under the agricultural policy are targeted accordingly. Our findings can also be related to those of the author Vidickienė (2017), who states that the role of women in introducing new efficiencies in agricultural activities could be essential, which is why it is important to include measures to support young qualified women in agricultural activity initiatives in rural development programmes based on a short food chain and enabling them to transfer knowledge to other farmers and the local population.

5. Conclusions

This article deals with a current issue in the field of rural development, which is analysed using multi-criteria decision analysis. As a result of the analysis, a model called DEX-SOCIAL was developed. The results presented in this article offer interesting starting points for further discussion in the context of research. The limitations we encountered in the research relates, on the one hand, to the consideration of all criteria that influence the assessment of the social and economic situation of women on farms and, on the other hand, to the limitation of the number that the programme still allows for a meaningful branching of the decision tree (limitation of the number of defined utility functions). We assume that we have covered all important criteria for assessing the social and economic situation of women on farms.

The results show that a stable economic security and position has a decisive influence on the final assessment of the position of women on the farm. The results of the variants in relation to the cohesion region in Slovenia were to be expected, due to the farming system, which is predominantly extensive in the Western Cohesion Region. The comparison of the variants, according to age, did not bring any big surprises. The younger generation of women has a higher level of education and is not as burdened by the hazards that can worsen their situation, while this can be seen in the plus-minus-1 analysis for the generation over 40 years old. From this, we can conclude that for women to have a stable social and economic position on farms, it is important that they became a successor at a younger age. This is, of course, a free decision of the individual and cannot be included as a criterion in the model. According to the results of the model, which assessed the economic situation for all the variants studied with a medium value, it should be emphasised that the results express the importance of achieving the goal of creating economically stable and well-paid jobs on farms, so that we can expect interest in agriculture from generation to generation.

The study leaves some research questions unanswered that would be useful to address in the future. It would be useful to conduct a similar study using the male population as an example, with the aim of identifying the criteria that are most important to them, in order to get a sense of the stability of the social and economic situation on farms. In any case, we assume that such a study will contribute to a broader understanding of the context of rural sociology and consideration by decision-makers at other levels, not only in the field of scientific research. We believe that, within the research we have presented, the chosen methodology is useful for similar social research analyses in the future, as well as being useful for a wider range of professions. Additionally, we can also add the small size and the non-representative nature of the sample as research limitations, because probabilistic methods are not described and some women working in agriculture do not fall within the category of those who can be included in an online study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., U.V. and K.P.; methodology, J.P., U.V. and K.P.; software, J.P., U.V., K.P. and Č.R.; validation, J.P., U.V., K.P., Č.R. and J.T.; formal analysis, J.P., U.V. and K.P.; investigation, J.P., U.V. and K.P.; resources, J.P. and U.V.; data curation, U.V. and J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, J.P., U.V., K.P., Č.R. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, J.P.; supervision, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as this type of study conducted does not necessitate an ethics board review per Slovenian guidance.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions (e.g., privacy, legal or ethical reasons).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bohanec, Marko. 2008. DEXi: Program for Multi-Attribute Decision Making User’s Manual. Ljubljana: Institute Josef Stefan, p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- Bohanec, Marko. 2017. Multi-criteria dex models: An overview and analysis. Paper presented at SOR 17 Proceedings, The 14th International Syposium on Operational Reserach in Slovenia, Bled, Slovenia, September 27–29; pp. 155–60. [Google Scholar]

- Borec, Andreja, Zarja Bohak, Jernej Turk, and Jernej Prišenk. 2013. The Succession Status of Family Farms in the Mediterranean Region of Slovenia. Sociologia 45: 316–37. [Google Scholar]

- Casel, Susanna Heldt, and Katarina Pettersson. 2015. Performing gender and rurality in Swedish farm tourism. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism 15: 138–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, D., D. Bertoni, F. Tesser, and D. G. Frisio. 2015. What factors encourage intrafamily farm succession in mountain areas? Evidence from an alpine valley in Italy. Mountain Research and Development 35: 152–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayal, K., B. L. Dhaka, M. K. Poonia, S. V. S. Tyagi, and S. R. Verma. 2013. Involvement of Farm Women in Decision-making In Agriculture. Studies on Home and Community Science 7: 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, Michal. 2016. A matter of family? An analysis of determinants of farm succession in Polish agriculture. Studies in Agricultural Economics 118: 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franić, R., and T. Kovačićek. 2019. The Professional Status of Rural Women in the EU. Brussels: Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/608868/IPOL_STU(2019)608868_EN.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2023).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Food. 2022. Strategic Plan of Common Agricultural Policies 2023–2027 for Slovenia. Lombergars Days 2022—Vineyard Consultation. Available online: https://www.kmetijski-zavod.si/Portals/0/lombergarjevi/predavanja/vinogradni%C5%A1ka/PREDSTAVITEV%20SKP%20-%20vinogradni%C5%A1tvo.pdf?ver=2022-12-05-125929-907 (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Muršec, Katica. 2018. Analysis of the Socio-Economic Position of Women on Farms in Podravje Region. Master’s thesis, University of Maribor, Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Maribor, Slovenia; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Pajnik, Mojca. 2000. Rural Women in the Process of Accession to the European Union: A Collection of Essays. Ljubljana: Open Society Institute—Slovenia. [Google Scholar]

- Puška, Adis, Andelka Štilić, Miroslav Nedeljković, and Aleksdandar Maksimović. 2022. Dex-Based Evaluation of Sustainable Rural Tourism in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Tourism and Hospitality 3: 919–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robnik, S. 2018. Kmečke ženske v Sloveniji. (Women on Farms in Slovenia); Ljubljana: MDDSZ. Available online: http://mddsz.arhiv-spletisc.gov.si/fileadmin/mddsz.gov.si/pageuploads/dokumenti__pdf/enake_moznosti/RaziskavaKmeckeZenske2018.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- Rosario, Miguel S. M., Fernando A. F. Ferreira, Amali Cipi, Guillermo O. Perez-Bustamante Ilander, and Nerija Banaitienė. 2021. “Should I Stay or Should I Go?”: A multiple-criteria group decision-making approach to sme internationalization. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 27: 876–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, Rachele. 2022. Small Farms’ Role in the EU Food System. European Parliamentary Research Service. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/733630/EPRS_BRI(2022)733630_EN.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Shortall, Sally, and Bettina Bock. 2015. Introduction: Rural women in Europe: The impact of place and culture on gender mainstreaming the European Rural Development Programme. Gender, Place & Culture. A Journal of Feminist Geography 22: 662–69. [Google Scholar]

- SI-STAT. 2016. Družinska delovna sila po spolu in povprečni starosti, po kohezijskih regijah, Slovenija, večletno (Family Labor Force by Gender and Average Age, by Cohesion Regions, Slovenia, Multi-Year). Available online: https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/sl/Data/-/1516110S.px/ (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- Trdin, Nejc, and Marko Bohanec. 2018. Extending the multi-criteria decision making method DEX with numeric attributes, value distributions and relational models. Central European Journal of Operations Reserach 26: 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidickienė, D. 2017. Attractiveness of Rural Areas for Young, Educated Women in Post-Industrial Society. Eastern European Countryside 23: 171–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindiš, Peter, Denis Stajnko, Peter Berk, and Miran Lakota. 2012. Evaluation of energy crops for biogas production with a combination of simulation modeling and DEX-i multicriteria method. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 21: 763–70. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).