Abstract

As a highly urbanized country, Japan is facing the phenomenon of a continuous migration of young people from rural areas to cities, leading to an aging and decreasing population in rural communities. Influenced by the pandemic, people began to reconsider the issue of population concentration in large cities, causing urban residents to become interested in returning to rural areas. The focus of this study is on the perceptions and relocation intentions of Japanese youth towards rural areas, particularly in Hanyu-shi, Saitama Prefecture. Through semi-structured interviews with 26 urban university students who live in urban areas, this study explores the factors that attract or hinder them from having rural lives. The survey results show that childhood experiences and current lifestyle preferences have influenced their views on rural areas. The main hindering factors include backwards infrastructure, communication difficulties, and limited job prospects. This study reveals a significant cognitive gap in urban youth’s attitudes towards rural life in Japan. The study emphasizes the need to eliminate these hindrances and enhance the attractiveness of rural areas to promote reverse urban migration. This study provides important insights for policymakers and urban planners, highlighting the necessity of formulating development strategies that meet the needs of urban youth residents, which is crucial for the sustainable revitalization of rural Japan.

1. Introduction

The global phenomenon of counterurbanization, characterized by a migration trend from urban to rural areas, presents varied implications across different geographical contexts. This shift, often a response to urban challenges such as congestion and pollution, reflects changing lifestyle preferences and societal values (Berry 1980; Tammaru et al. 2023; Herrero-Jáuregui and Concepción 2023). In Western countries, factors driving counterurbanization include improved quality of life, access to nature, and cost-effective living (Halfacree 2009). Furthermore, technological advancements that facilitate remote work significantly endorse this trend (John 2020; Hart 2020).

In Asia, particularly Japan, counterurbanization is a relatively recent development. Japan’s approach is characterized by government-led initiatives aimed at rural revitalization and encouraging urban-to-rural migration amidst challenges such as population decline, aging demographics, and sustainability concerns in rural areas (André 2002; Cabinet Secretariat 2020). Dilley’s research on Japan’s counterurbanization found that national urban-to-rural migration is limited, highlighting the need for further research to enhance understanding of these trends (Dilley et al. 2022). These trends emphasize the necessity for adaptive national planning strategies to leverage counterurbanization for sustainable rural development, considering regional disparities and underlying motivations for migration (Ochiai 2023; OECD 2020). The Japanese countryside is increasingly depicted in nostalgic and positive terms, aiming to promote counterurbanization and mobility-led local development. It is observed that people are attracted to rural areas that exude positive emotions and a sense of community (The Economist 2018). This stands in contrast to Western experiences, where consumer choices often drive such movements, as discussed by Phillips (Phillips et al. 2021) and Philip and Shucksmith (Phillip and Shucksmith 2003).

Since the 1970s, Japan’s counterurbanization, characterized by a population shift to suburban areas in response to soaring urban land prices (Morikawa 1988), has set the stage for the country’s more recent demographic trends, including the most rapid population decline in Asia since 2010. Recent demographic trends show that Japan has experienced the most rapid population decline in Asia since 2010, and this has become a significant societal concern (Yamashige 2014; Karasawa and Yeung 2023). Rural regions are suffering from depopulation and a decreasing number of young residents, jeopardizing the maintenance of traditional cultural industries and agricultural livelihoods. The ongoing rural-to-urban migration trend amplifies these issues, threatening both the economic viability of these areas and the well-being of their communities (Richarz 2019; Horiuchi 2019). To counteract these trends, the Japanese government has implemented various initiatives to reinvigorate rural areas, including incentives designed to attract families from the Tokyo region to relocate to the countryside (Corday 2023). Despite these efforts, reports from the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism reveal a persistent migration from rural to urban locales (Klien 2020; MLIT 2002), which contributes to the depopulation of these areas and presents numerous socio-economic difficulties, especially in terms of youth succession (Sakuno 2019).

Addressing the challenges of rural depopulation necessitates a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing the migration decisions of young individuals (Schorn 2023; Izuta et al. 2016). Surveying the mobility and migration patterns of this demographic may also play a role in shaping effective counterurbanization strategies (Pileva and Markov 2021). Young individuals often exhibit reluctance towards rural residency due to perceived disadvantages, such as limited career prospects, educational opportunities, and public services when compared to urban environments (Yamashita 2019; Du 2017). To mitigate rural youth migration, it is imperative to enhance skill development, generate employment and entrepreneurial avenues, improve access to education, housing, digital infrastructure, public amenities, and markets, and foster a stronger sense of belonging and attachment to rural communities (MAFF 2023; Japanese Cabinet Meeting 2023).

Place attachment refers to the bond that develops between individuals and their meaningful environments (Scannell and Gifford 2010). It can be conceptualized within a three-dimensional framework that integrates person, process, and place. Research on young people’s place attachment has primarily focused on their attachment to the rural areas where they grew up or their attachment to urban and rural areas after moving to cities (Eacott and Sonn 2006; Rérat 2014; Wiborg 2004; Mao et al. 2023). Additionally, in line with national policies and global sustainable development goals, encouraging urban youths to focus on and strengthen their attachment to rural areas is crucial for enhancing the quality of life, economic opportunities, and environmental sustainability in these areas (Odagiri 2013; MAFF 2018). However, current research on the attachment and relocation intentions of urban students towards rural areas is limited. Understanding the attitudes and perceptions of young urban residents towards rural areas is vital for supporting and developing rural communities (U. Dana-Alina et al. 2021; Svendsen 2018). Preliminary studies on university students in urban areas of Japan have shown a high degree of affection and emotional connection to rural areas, but a low willingness to relocate. Therefore, the specific motivations of these young people to visit and relocate to rural areas need to be understood (Mao et al. 2023). Some studies suggest that participation in rural community and agricultural activities can significantly deepen these students’ emotional connection and future residency intentions in rural areas (Ida and Fujii 2004; Takuya Tarasaki 2012). However, research subjects have mostly been individuals born in rural areas, with few studies focusing on young urbanites moving to rural areas.

This study focuses on university students, who are typically more mobile and receptive to new environments (Kuh et al. 2006). Attracting these educated young adults to rural areas can catalyze local economic growth and support sustainable development (Liu and Li 2017). A deeper understanding of their attachment to rural settings can shape policies that promote their long-term residency in these areas. A deeper understanding of their attachment to rural settings can shape policies that promote their long-term residency in these areas. The study by Amare et al. (Amare et al. 2021) reveals that a combination of urban economic challenges, the allure of rural living, and the quest for a better work-life balance are complex factors driving Nigerian youth towards counter-urban migration. The engagement of rural youth within their communities and their emotional bonds profoundly affects their perceptions and migration choices. Active community involvement is shown to result in sustainable outcomes of projects, and a strong sense of attachment to rural areas motivates youth to stay or return to their hometowns. Comprehending these elements is essential for advancing community development and persuading young people to remain in rural areas (Majee et al. 2020).

The research selected Hanyu-shi in the Saitama Prefecture as our focus due to its status as a suburban agricultural area. A preliminary investigation into students from diverse origins indicated a predominant preference for suburban locales when considering future relocation, coupled with a willingness to engage in regional development initiatives (Mao et al. 2022). Consequently, Hanyu-shi, exemplifying a suburban enclave within the Greater Tokyo conurbation, was chosen as the subject of our research. Hanyu-shi is committed to the provision of safe and reliable agricultural outputs, fostered by its local climate, and complemented by accessible information and support (Hanyu-shi 2015). The municipal strategy encompasses fostering land infrastructure development while concurrently conserving the bucolic landscape and nurturing a symbiotic relationship with the environment, thus enhancing the pastoral charm (Hanyu-shi 2023). Compared to other remote rural areas, Hanyu-shi enables easier access for people from the Greater Tokyo Area, and the local government’s proactive agricultural promotion policies, as well as support for local agricultural NPOs and agricultural organizations, have led to many people from nearby large cities going to Hanyu-shi for agriculture on weekends (Hanyu-shi 2018). For example, the research subjects of this study are two local organizations (NPO) Udokuseiko (Cabinet Office 2023) and Bokura no Shukaijo (Bokushu 2018), which are such places.

This study aims to fill this gap by exploring the attitudes, attachment and the factors influencing people’s motives regarding relocating to rural areas, particularly in Hanyu-shi, Saitama Prefecture. This study, concentrating on Hanyu-shi in Saitama Prefecture—an area where urban and rural elements uniquely intertwine—employs semi-structured interviews and surveys to explore how youths’ perceptions affect their intentions to relocate. The research aims to yield insights for policy formulation and rural revitalization while striving to offer a detailed understanding that informs strategies for sustainable rural development and youth engagement in Japan.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Background

This study selected the agricultural activity area in Hanyu-shi, Saitama Prefecture as the study site for our questionnaire and interviews. Hanyu-shi is located in the northeastern part of Saitama Prefecture, approximately 60 km from downtown Tokyo and 40 km from Saitama City. It is bordered by Kuki City to the east and south, Gyoda City to the west, and Gunma Prefecture to the north, separated by the Tone River. The region spans 10.25 km east to west and 6.71 km north to south, covering an area of 58.64 km2 (Hanyu-shi 2022).

Hanyu-shi is actively promoting citizen collaboration and participation. In this context, our research approach included direct inquiries and phone surveys conducted through the local city office, identifying organizations involved in local activities and obtaining permission to conduct our research (Hanyu-shi 2023). Ultimately, two local non-profit organizations (NPO)—Udokuseiko (Cabinet Office 2023) and a community activist group, Bokura no Shukaijo (Bokushu 2018)—granted us permission to participate in their activities and conduct academic research (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(Left) NPO Udokuseiko, (Right) community group Bokura no Shukaijo.

The organizations in question are united in their overarching mission: to foster the development of a low-carbon society, champion sustainable circular communities, stimulate regional revitalization, and enhance food self-sufficiency. Central to their ethos is the principle of coexisting harmoniously with nature, enriched by the tangible experiences of all four seasons (Cabinet Office 2023). The activities they offer, such as hands-on experiences in wheat and rice cultivation, along with goat rearing, epitomize their commitment to a “semi” self-sufficient lifestyle. They meticulously curate these experiences to ensure participants are engaged in tasks that are manageable and align with their inherent skills and abilities, thus avoiding undue exertion or strain.

Both sites are situated within the agricultural promotion sector of the urbanization control zone. For the purposes of this study, the research team opted to survey and interview university students who are studying in urban areas but were not born in Hanyu and have attended or participated in various events and lectures. Specifically, these students were involved in Udokuseiko’s rice farming lectures and Bokura no Shukaijo’s wheat lectures.

2.2. Research Approach and Data Interpretation

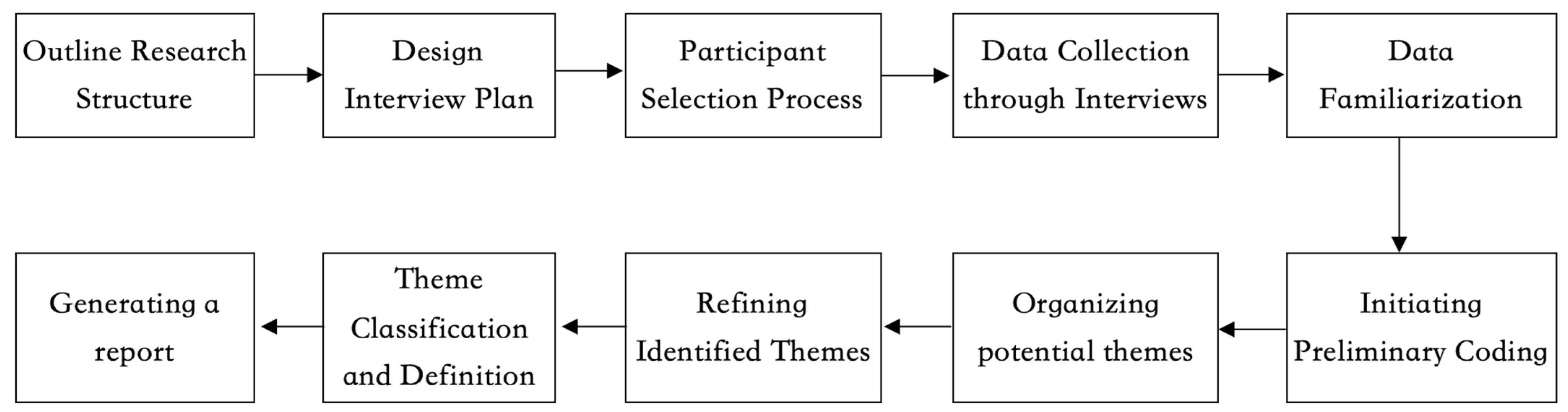

For the analysis of collected data, thematic analysis was employed, a robust technique for qualitative data examination (Braun and Clarke 2006). This approach involves several critical stages to systematically decode and interpret the data (see Figure 2). Initially, the research team familiarized themselves with the interview data through active involvement in the interview process, transcription, and meticulous review of the transcripts. The next phase involved generating initial codes by identifying key elements within the interview data, which served as foundational descriptors for the entire dataset. Subsequently, the organization of potential themes was engaged by examining commonalities and patterns across different codes identified in the interview data (Adevi and Mårtensson 2013). This step was crucial in developing coherent themes that accurately represented the data. Following this, the themes were refined to ensure they were meaningful and distinct from one another, ensuring the thematic structure accurately reflected the interview content. In the final stages of analysis, each identified theme was carefully named and defined, providing clarity and distinctiveness to each theme. This step was pivotal in differentiating between various themes and ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the data. The culmination of this process resulted in the formulation of an analytical report that succinctly presented the findings, offering clear insights and interpretations of the thematic analysis conducted.

Figure 2.

Research framework (Luo et al. 2021).

2.3. Participants

The study involved conducting interviews from September 2022 to July 2023 with 26 university students, comprising 10 males and 16 females, who engaged in activities centered on learning and exchanging agricultural skills in Hanyu-shi, Saitama Prefecture. Of these interviews, 20 were conducted face-to-face, while the remaining 6 were executed via Zoom. All interviews were undertaken with the prior consent of the event organizers, ensuring ethical considerations were maintained (Takahashi 2009). The inclusion criteria for participants were that they must be at least 18 years old, enrolled in a university, and currently living in an urban area. Drawing upon the methodologies outlined by Gill and Van Manen (Gill 2014; Van Manen 1989), this study employs interviews to delve into diverse individual experiences, thereby offering foundational insights for academic inquiry. Typically, research in this field includes a participant range of 7 to 28, aligning with common practices in qualitative studies (Lomas et al. 2021; Alirhayim 2023; Bailey et al. 2021; Vergara-Perucich and Arias-Loyola 2024; Moganedi and Mudau 2024; Hyassat et al. 2023; Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2023). Furthermore, according to Gill (2014), a sufficient sample size is considered attained when the data yields clear and discernible interpretations, and the inclusion of additional participants does not contribute novel insights, thus negating the necessity for data saturation in the study.

The age of the participants varied between 19 to 23 years, with an average age of 21 years (SD = 15.4), and all respondents had visited agricultural areas other than Hanyu-shi. The participants effectively captured a diverse range of individual experiences without yielding redundant information. Consequently, this number of participants is adequate to provide comprehensive insights for the study’s objectives.

The study employed semi structured interviews as the primary data collection tool. Its primary objective was to delve into university students’ perceptions of, and attachment to, rural areas in Japan. Specifically, the research explored their general feelings and inclinations toward rural Japan and contrasted these with their sentiments specifically about Hanyu-shi. The study further probed their intentions to relocate to rural areas in the future, delving into their reasons and motivations. Previous experiences, both positive and negative, of visiting rural settings were discussed to provide context. Lastly, the research examined their expectations for future engagements, whether as visits or potential residency, in these rural areas. To minimize psychological pressure on respondents, interviews were conducted anonymously, with participants only being asked about their age, gender, current city of residence, and birthplace.

2.4. Materials

The study crafted a semi-structured interview guide consisting of core questions that were consistently presented to all participants. This approach ensured both consistency and flexibility during the interviews. The primary questions were as follows:

- What are your overall impressions and emotions about your past visits to rural areas in Japan?

- Do you have any intentions to relocate to a rural area in the future, and share your reasons for this?

- How would you describe your overall impressions and feelings about Hanyu-shi?

- Are you considering relocating to Hanyu-shi in the future? If so or not, what are the reasons behind this decision?

- Based on your experiences and perceptions, what suggestions would you offer for the future development of rural areas in Japan?

- Simple questions about their personal experiences.

This structured approach facilitated a systematic collection of responses while allowing participants to provide in-depth insights and share their personal experiences. Interviews were recorded for transcription and then summarized and translated into English. The research team conducted a total of 26 individual interviews, each lasting approximately 25–40 min (Table 1). The respondents determined the interview duration, with most interviews occurring post-activity. Participants were informed of the interview’s purpose and process in advance. All expressed their willingness to participate in the research. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, no identifying information was recorded. The study adhered to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration (Goodyear et al. 2007) and is non-invasive. The researchers obtained verbal consent from all participants before conducting the survey and received permission from the university for the research, which did not necessitate any formal ethical approval documentation. As per the guidelines of the Japanese ethical committee, the research, which includes non-medical studies involving surveys and evaluations of education or work-related activities, is acceptable provided the data is protected and non-invasive (Takahashi 2009). Hence, the institution did not mandate the submission of a research proposal for ethical review.

Table 1.

Profile of anonymous respondents.

3. Results

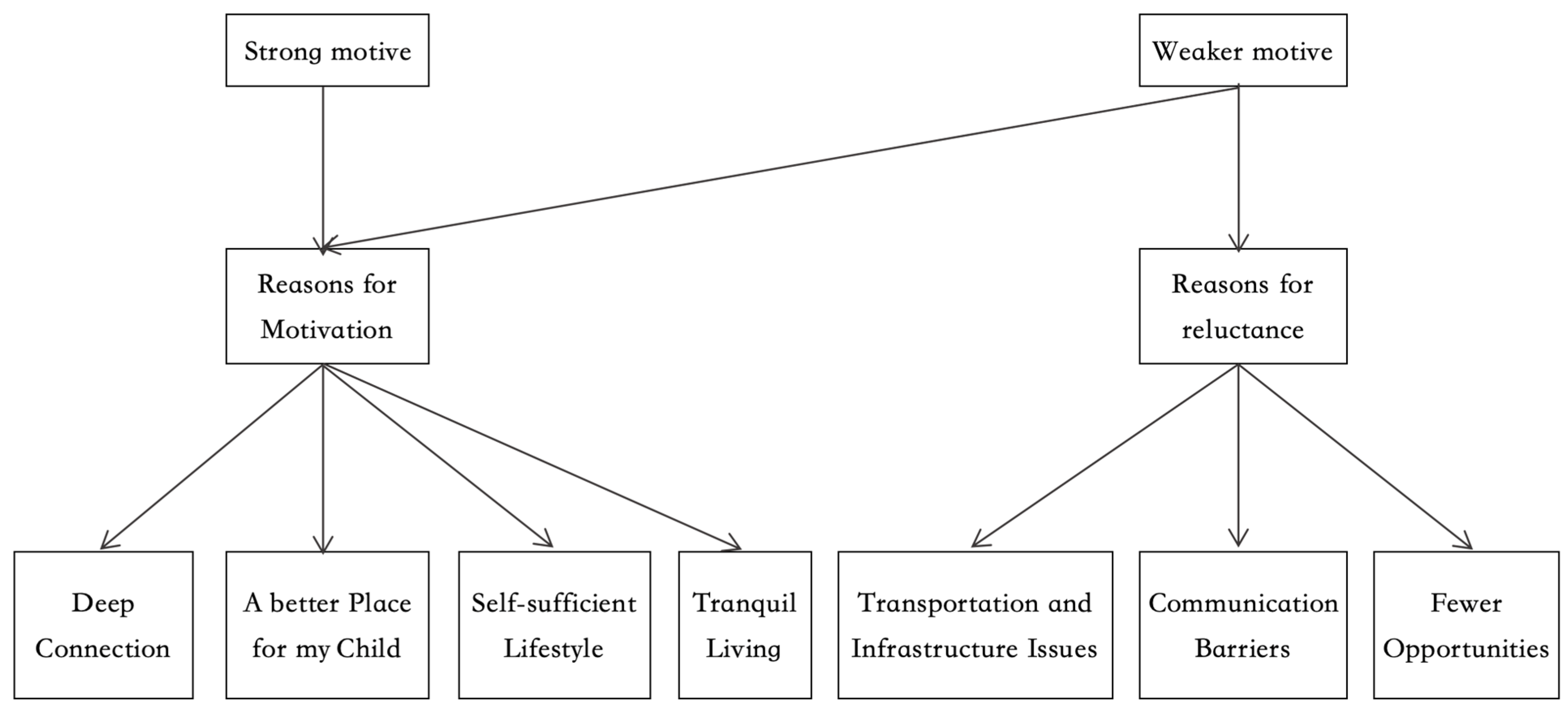

Students come to Hanyu-shi with different motives. According to the analysis results, most of the interviewees showed a weak willingness to live in rural areas in the future but a high willingness to visit rural areas and participate in activities. The first section explores students’ motives to relocate to rural in the future, and the reasons that weaken students’ motives for living in rural in the second section. Each of these themes is discussed in the following sections using the informants’ own words to explain their unique perspectives and experiences.

3.1. Strong Motive

In the context of research, the term “strong motive” refers to the participants’ expressed intense inclination to relocate to rural areas, as articulated during their interviews. This desire encompasses their positive perceptions of and reasons for considering such a transition to rural locales. From the testimonies provided, the research team identified five distinct themes that encapsulate the predominant reasons for the participants’ fervent inclination towards rural relocation. These themes are:

- “Deep Connection”—signifying a profound bond or affiliation with the rural environment.

- “A Place for my Children”—indicating a desire to provide a better environment for offspring.

- “Self-sufficient Lifestyle”—denoting the aspiration to lead a life where one largely provides for one’s own needs.

- “Tranquil Living”—reflecting the pursuit of a peaceful and serene lifestyle away from urban hustle.

These predominant themes are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The framework of motives to relocate to rural areas.

3.1.1. Deep Connection

Since 1999, the Japanese government has been promoting rural exchange initiatives and actively encouraging individuals to engage with rural areas (MAFF 2020). For instance, the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries launched an agritourism program, highlighted by popular songs aimed at encouraging people to visit and stay in scenic rural areas, especially during the pandemic (MAFF 2022). One objective of these strategies is to foster deeper connections and interactions between urban residents and rural areas.

When inquired about their motivations to reside in rural areas in the future, the most frequent response pointed towards a deeper connection with such areas. Interviewees expressed that in urban environments, beyond their immediate circle of friends, there’s limited interaction with strangers, a phenomenon exacerbated post the 2020 COVID-19 outbreak. Social contacts are essential daily behaviors of urban residents and are positively related to better health, well-being, and quality of life. Reducing social behavior will lead to an increase in social isolation and loneliness (de Jong-Gierveld et al. 2006). The urban residential setting often leaves neighbors unfamiliar with one another. One male student mentioned, “Yes, September is a vacation month, and I often find myself isolated at home. But during agricultural exchanges here, everyone is engaged in similar tasks, making it easier to connect. I’ve made several friends here, and I cherish this feeling. Though not immediately, I do see myself settling in a rural setting in the future, forging beautiful connections.” (Male, 21 years old).

Apart from interpersonal connections, many respondents emphasized the value of connecting with the natural environment and the land. A soon-to-be graduated female student shared her perspective, “Given the pressures of graduation and job-seeking, I make it a point to visit here, to immerse in the natural beauty. For me, it’s not just about people; I’m rather introverted, but I love talking to the goats here. I’ve grown fond of some of the lambs born here; they feel like friends to me. Every visit, I look forward to the pastures, feeding them, and caressing them. I genuinely feel a deep connection. I wish to reside in such an environment in the future.” (Female, 22 years old). With the progress of urbanization, many urban-born children lose touch with the significance of rural areas and natural encounters. Bonding with nature and animals offers profound emotional healing. This realization is increasingly dawning upon the younger generation, making them more inclined towards rural regions.

When asked about their impressions of the Hanyu region, respondents often expressed very positive sentiments. One 21-year-old male commented, “Here, I’ve made many good friends and acquired some agricultural knowledge. I believe this knowledge will be useful in the future. At the very least, I hope to set up a small agricultural plot on my balcony after graduation.” However, when probed about their specific intentions to move to the Hanyu region, the enthusiasm did not seem as high as the general rural migration intent. Another 20-year-old male reflected, “Hanyu is great and has wonderful connections, but it’s not the place that left the most profound impression on me. I prefer places with mountains, like Karuizawa, or being on islands, perhaps relocating to Amami Ōshima in the future, meeting new groups of people, and establishing a new community.”

The insights from these discussions indicate that this profound sense of connection might play a central role in determining students’ potential inclination to migrate to rural areas in the future. The lesser inclination to relocate to Hanyu-shi compared to other regions could possibly be attributed to the frequency of their visits. Some students pointed out that Hanyu, in contrast to their envisioned idyllic life, lacked memorable landscapes due to its absence of forests, water bodies, and mountains. Numerous participants recognized that owing to academic and occupational pressures, coupled with the shift to online work paradigms following the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, they are increasingly attracted to safer, picturesque rural regions, cultivating deeper ties with peers, the natural environment, and wildlife.

3.1.2. A Place for My Children

For the participants, their impressions of Japan’s rural areas, including Hanyu-shi, were overwhelmingly positive and optimistic. This sentiment is often rooted in their childhood experiences, whether those were familial trips or school-organized excursions to the countryside. Japanese primary, middle, and high schools traditionally conduct annual group trips, known as “study tours”, allowing students to explore various locales. Many participants recounted their first encounters with rural landscapes and agricultural settings during such trips. A 20-year-old female recalled, “I remember family trips and school excursions to the countryside when I was young. Although I can’t pinpoint the exact locations, the joy I felt is still vivid.” Another 19-year-old male emphasized, “Childhood memories play a significant role; experiences were freer and more genuine then. I fondly remember rolling around in the fields, which offered a sense of freedom starkly contrasting the city’s ambiance.” A 21-year-old female described her first rural encounter, stating, “My initial exposure to the countryside was during a primary school study tour to a suburban agricultural region near Tokyo. The participants experienced the joy of harvesting wild vegetables, and one distinctly remembered pulling radishes. For them, it was the first time they truly understood where their daily food came from.”

Japan is undergoing a significant decrease in birth rates, as highlighted by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare’s “2020 Vital Statistics of Japan (final figures)”. Projections for 2023 and beyond indicate a persisting downward trajectory, with anticipated births dropping to around 370,000 by 2070, well below the 400,000 mark (MHLW 2020; Kokuro Ichimasa 2022). Several studies attribute this decline to the immense pressures, a growing diversity of life values, and an awakening sense of individualism faced by the younger generation in their daily lives. Struggling to manage such stressors often results in a reluctance to start families or have children. With urbanization on the rise, birth rates in urban areas are notably lower than in rural zones. This trend may correlate with an increasing sense of individualism among the youth, leading many to prioritize personal space. Thus, the government has been launching initiatives to promote childbirth and instill positive family and childcare values among the youth.

In the responses, it emerged that while most young individuals aim to kickstart their careers in metropolitan areas, post-graduation, a significant portion expressed a preference for relocating to rural regions if they decide to start families. A 22-year-old female articulated, “Upon graduation, I hope to gain professional experience in a big city. However, I wish my child could grow up freely in a rural setting.” A 23-year-old male voiced concerns about urban pressures on children, stating, “Urban expectations and pressures on kids are excessive. I’ve encountered children pushed by their parents to excel and be remarkable, yet they don’t seem happy. I wouldn’t want my child to grow up in such an environment; relocating to the countryside could be an excellent way to offer them more freedom and possibilities.” Another participant said, “The children I observed in Hanyu seemed genuinely content. I believe I would’ve been just as joyful growing up in such surroundings.”

Some young individuals consider Hanyu a viable option for raising their children, as it’s relatively close to Tokyo, potentially allowing for work-city balance while offering their children a more natural and liberating upbringing. A 21-year-old female expressed, “I might consider Hanyu because it’s at an acceptable distance from Tokyo. The beautiful nature and farmlands there could be a playground where my child could happily engage with local kids.” However, some expressed concerns about rural education standards, especially the lack of high schools in many areas, which might necessitate relocation. A 22-year-old female pondered, “Growing up in the countryside until the age of 10 might be great for a child. Yet, for better educational opportunities, I might have to move to a city or ensure they attend a city-based university.”

These interviews underscored that fond childhood memories of rural areas greatly influence the participants’ current positive disposition towards these regions. When discussing potential relocations to rural areas, many brought up the welfare of their future children. Notably, many young participants, especially females, expressed that they would prioritize a stress-free environment for their children, leaning towards the countryside for raising them. These young individuals seem to have a mature and forward-looking perspective on their future families, more so than one might initially assume.

3.1.3. Self-Sufficient lifestyle

The 2011 earthquake, commonly referred to as the 311 Earthquake, coupled with the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, substantially limited many residents’ daily activities in Japan that times. Particularly during the 311 Earthquake, the sellout situations in urban supermarkets and convenience stores raised considerable concerns among the populace. During the 2020 pandemic, residents of major cities like Tokyo faced significant restrictions on outdoor activities, except for essential work and purchases. These events, influenced by both natural and health crises, triggered a renewed reflection on living standards among many, leading to increased interest in self-sufficient lifestyles.

“In the aftermath of the Eastern Japan earthquake, I was spending my winter vacation at my grandmother’s place in the rural Shizuoka. While I heard that many of our relatives in Tokyo were experiencing food shortages, we faced no such problems in the countryside. We grew rice, wheat, various vegetables, and engaged in poultry farming and fishing. We were worried about our friends and relatives in Tokyo, but we weren’t afraid for our immediate well-being.”(Female, 23 years old)

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, out of concern for getting infected, my family moved to the countryside for a while. We had none of the urban concerns there. For the first time, I felt the freedom of rural life, free from the worries of the pandemic. Our neighbors would often gift us vegetables they grew, and I found such a self-sufficient way of life truly appealing.”(Male, 22 years old)

“A film I adore, ‘Little Forest,’ made me envy the protagonist’s choice to leave the big city and embrace rural life. Watching her grow and cook her food inspired me. Perhaps, someday, I might lead a similar life.”(Female, 21 years old)

The term “return to the countryside” is receiving increased attention in Japanese society, reflecting shifts in societal values. The three community organizations in Hanyu-shi promote a self-sufficient lifestyle that’s both eco-friendly and health conscious. Many students interviewed were just coming off agricultural activities, with many mentioning that harvesting crops was among their annual highlights. Even visiting just once a month felt rewarding. “I would take home the freshly harvested potatoes, lotus roots, carrots, and herbs allocated to me by the community. I would cook with these ingredients, acknowledging and thanking them for the nourishment. I learned this gratitude during agricultural exchange activities in Hanyu, and I wish more people could experience this.”

In conclusion, as young individuals’ understanding of society evolves, their openness to diverse lifestyles deepens. The self-sufficient lifestyle has become a reason many are drawn to rural life. Youngsters are inclined towards challenging activities, such as mastering new agricultural techniques from scratch. Moreover, in a country like Japan, known for frequent earthquakes and recently impacted by the 2020 pandemic, they have come to perceive urban vulnerabilities, making them more willing to explore the potentials that rural life offers.

3.1.4. Tranquil Living

When asked about their impressions and views of rural areas, most of the college students felt that such places are serene, peaceful, and comforting. These sentiments are often tied to elements such as “expansive landscapes”, “lower population density”, “fresh air”, and “rich natural environments”. The pressures brought about by urbanization, including job-seeking stress, interpersonal tensions, and academic pressures, are the realities these young individuals face. According to recommendations by the Japanese government, educational institutions should actively promote students’ interactions with nature, and various incentives have been introduced for student travel. Close encounters with nature and participation in agricultural activities are believed to bring calmness, soothe the mind and body, and alleviate stress. Hence, visiting these tranquil rural regions serves as a means for young people to unwind.

Several students expressed that being in these natural, rural settings allows them to let go of many mental burdens, providing relief from the constant strain of everyday life. “I’m quite an introverted individual. In crowded places, I often feel inhibited, overthinking many aspects and generating a lot of worries. I enjoy driving alone to serene rural areas or hot spring villages; for me, it’s a form of ‘recharging,’” shared a 22-year-old male.

“In large cities, there are numerous entertainment options, and it’s bustling. But occasionally, I feel that traveling to rural areas, immersing oneself where nobody knows you, is also refreshing. In such situations, I get a plethora of new ideas and opportunities for self-reflection.”.a 20-year-old female recounted

“After participating in agricultural experiences in Hanyu, I would often walk alone to the train station, strolling along the paddy ridges, relishing the pleasant aromas in the air. The natural scenery always instills a sense of peace in me. On those days, I always have a good night’s sleep when I return home.”.mentioned a 24-year-old female

While a bustling social life is an element of a vibrant lifestyle, tranquility and a quiet living environment seem equally pivotal for the younger generation. Being constantly in lively and hectic settings can induce feelings of tension. Prolonged exposure to such strain is considered potentially detrimental to mental well-being (Peen et al. 2010). Peaceful environments positively influence one’s physical and mental health, promoting better rest. Echoing this, the tranquility that students find in rural areas has a positive effect on their mental stress relief (Dahmann et al. 2010). As many have pointed out, these rural escapades serve as a “recharging” experience for them.

While depopulation has led to substantial outflows from rural regions, the interview findings suggest a predominantly positive inclination toward resettling in these areas. A growing number of young individuals are becoming cognizant of these challenges. Despite facing uncertainties, deep within, they seem willing to actively seek balanced solutions for the future. “I hope that in future Japan, urban dwellers won’t be viewed as more stylish and affluent, while rural areas are seen as backward and impoverished. During my study abroad stint in the U.S., I observed that individuals residing in rural parts appeared to experience heightened happiness and prosperity,” articulated a 23-year-old male.

3.2. Weaker Motive

The “Weaker Motive” category reflects respondents who acknowledged such motives but displayed hesitation when asked about their recent visits to rural areas. Upon analyzing the causes of these hesitations, the researchers categorized the reasons for diminishing motives into three themes: “Transportation and Infrastructure Issues”, “Communication Barriers”, and “Fewer Opportunities” (Figure 3).

3.2.1. Transportation and Infrastructure Issue

One of the paramount challenges impeding the development of rural societies is related to public transportation and the modernization of outdated infrastructure. While governmental initiatives have been advanced to address these concerns, a substantive resolution is often hindered by financial constraints. A recurrent sentiment among many respondents was their willingness to visit the countryside, but the inconvenience of transportation stood as a substantial barrier.

For instance, a 20-year-old male commented, “Every time I visit Hanyu for activities, I have to meticulously plan around the bus schedule. With only two bus services daily, missing the morning one means I’d either must traverse a significant distance on foot or resort to taxis. I find it challenging to envision a life in such settings, foreseeing immense inconveniences.”

Another 21-year-old male stated, “I’m in the process of obtaining my driving license, without which mobility seems daunting. Yet, the costs associated with learning to drive, and subsequent expenses of purchasing or leasing a vehicle, exert financial pressures. An enhanced public transportation system would be a boon.”

The cost and inconvenience associated with commuting to rural areas appeared to be a common grievance among students. Given the relatively higher transportation costs in Japan, missing a scheduled public transport could lead to exorbitant taxi fares—or worse, situations where taxis are unavailable—requiring several hours of walking. Such scenarios elicited underlying apprehensions among the respondents.

Moreover, when it came to rural amenities, there was a consistent expression of dissatisfaction. A 21-year-old female remarked, “I struggle with the sanitation standards in rural restrooms. The scarcity and the occasional subpar conditions leave me hoping for improvements in sanitary facilities.”

A 22-year-old male recounted his experience in Hanyu, “During my stays, I’ve been in houses without air conditioning. Winters involved burning coal, which was stifling, while summers were swelteringly hot. I’d prefer visits during milder seasons.”

Describing her experience, a 21-year-old female expressed, “The difficulty in locating convenience stores or eateries was frustrating. Once, I spent an extensive period searching for a store to buy insect repellent. To my dismay, I eventually found a sign indicating the nearest ‘Family Mart’ was 10 km away—it felt overwhelming.”

Lastly, a 23-year-old female highlighted a more profound concern: “The sparse street lighting in rural areas evokes a sense of fear in me. I’d prefer departing during daylight hours. The idea of living alone in the countryside becomes less appealing due to such anxieties.” These testimonies underline a set of genuine infrastructural and amenity-based challenges that might act as deterrents for young individuals contemplating life in rural Japan.

3.2.2. Communication Barriers

While discussing their apprehensions related to rural regions, several interviewees indicated feelings of unease arising from rural social communication, primarily due to their preference for maintaining certain social boundaries. Interestingly, this sentiment was echoed by both intrinsically motivated and less motivated respondents. A distinction between the two groups was observed: while the intrinsically motivated were more receptive to deep engagements, the latter group felt somewhat overwhelmed by profound interactions, expressing a penchant for solitary peace.

The effusiveness of rural residents, while generally well-received, seemed to occasionally instill a sense of pressure among the respondents. A few interviewees mentioned that their inclination towards the countryside for its tranquil ambiance sometimes inadvertently ensnared them into social events, leaving them somewhat out of their depth. For instance, a 22-year-old female remarked, “I cherish immersive rural experiences and agricultural engagements, but sometimes the unexpected ‘agricultural interaction parties’ unsettle me. I find it challenging to navigate ways to decline such invitations.”

A 21-year-old male reflected on the perceived lack of privacy in rural communities, stating, “The intricate web of gossip and close-knit interactions among neighbors and relatives in the countryside can seem invasive. News about personal relationships, like who one might be dating, becomes common knowledge swiftly. I understand the inherent warmth and kindness, yet I yearn for a semblance of privacy and personal space.”

Speaking about Hanyu, another 22-year-old female noted the distinctiveness of its residents compared to those in urban centers like Tokyo: “The warmth in Hanyu is palpable. People, even those you’ve met just once, would enthusiastically greet you on the next encounter. As an introvert, I sometimes find myself at a loss, unsure how to reciprocate such overt affection.”

Additionally, regional dialects emerged as another significant impediment to smooth communication. Many students relayed difficulties in comprehending locals, especially during interactions seeking directions or assistance. The complexity of rural living became evident to the respondents, prompting them to reconsider the practicality of such a lifestyle. For instance, a 22-year-old male recounted a situation where he and his companions got lost en route to a rural camping site. When they asked an elderly local for directions, they struggled to understand his dialect, leading to prolonged confusion and discomfort. This experience highlighted for them the potential challenges of adapting to rural communication styles, akin to learning a new language, which seemed daunting. These accounts underscore the importance of navigating and understanding rural social dynamics for individuals contemplating long-term residency in these areas.

3.2.3. Fewer Opportunities

For the younger generation, the ambition to seize opportunities, demonstrate their talents, and create societal value during their prime years is a universal aspiration. However, the limited employment prospects in rural areas seemingly tilt the scales unequivocally towards urban living. Japan’s government, recognizing this discrepancy, initiated the “Local Revitalization” policy in 2011. This policy aimed at promoting local tourism and creating more employment opportunities in the countryside. Although the policy has yielded some positive outcomes, the majority of rural regions still grapple with diminishing job prospects and a dwindling presence.

Several respondents opined that even for similar roles, such as civil service positions, urban areas offer considerably higher salaries. Hence, despite being aware of the reduced cost of living in rural settings, they still lean towards urban life. A 22-year-old male stated, “Financial stability remains pivotal. I wish to amass wealth to create more possibilities for my future. Currently, I find it challenging to envision such prospects in rural areas. I hope the government can someday offer more incentives for relocating to the countryside and better employment opportunities.”

The recent pandemic has reshaped some perceptions. A 22-year-old female remarked, “The onset of the COVID-19 crisis led many companies to adopt remote working systems, momentarily making relocation to the countryside seem feasible. However, post the crisis, as life regains its normalcy and companies resume in-person operations, the idea loses its allure. Living remotely, say in Hanyu, would entail a two-hour commute, which I’m not inclined towards.”

Another 23-year-old male, contemplating entrepreneurship post-graduation, shared, “It appears cities still house the lion’s share of opportunities. Perhaps, after accruing sufficient capital in the city, I might consider establishing a venture in the countryside. But not now. Post-graduation, the urban landscape, teeming with challenges and possibilities, beckons. An immediate shift to the countryside might dampen my zeal.”

Echoing a similar sentiment, a 22-year-old male commented, “Opportunities or the lack thereof, dictate my reservations about rural living. I hope for a day when the countryside can match the city’s prospects. Until then, the challenge seems insurmountable.” These narratives shed light on the economic determinants influencing the younger generation’s preference for urban settings over rural ones. The battle between the allure of potential urban wealth and the tranquility of rural life remains a decisive factor in their future habitation choices.

4. Discussion

Young Japanese individuals’ perceptions of rural areas are multifaceted. Their motives for considering relocation to these areas and the factors that weaken such motives are crucial for policymakers and local governments in Japan (Majee et al. 2020). By understanding these aspects, there’s potential for crafting policies and strategies that can attract more youth to rural regions, addressing demographic challenges and revitalizing these communities.

4.1. Motivations for Future Residency in Rural Areas

A study reports that urban dwellers are increasingly motivated to move to rural areas due to feelings of loneliness, stress, and economic pressures experienced in urban settings (Yun et al. 2016). The tranquility and freedom offered by rural environments promise a more serene and relaxed state of mind and body (García-Romero et al. 2023). Activities such as gardening and the influence of a green environment can divert attention from stress stimuli, thereby reducing anxiety prevalent in everyday urban life (Koay and Dillon 2020; Coventry et al. 2021). Natural settings are shown to decrease sympathetic nervous system activity, alleviating mental stress (Yu and Hsieh 2020). Recent research indicates that post-COVID-19, some nations have been advancing policies for rural residency, advocating for economic enhancement and agricultural development to foster balance and harmony between urban and rural areas (OECD 2020; MAFF 2020).

In the study of the relationship between young people and rural areas, this research identifies the potential for rural environments to offer “deep connections” to the youth. These green environments facilitate more natural communication with others, allowing individuals to relax, be themselves, and open up, in contrast to urban settings where shyness and self-concealment are more common (Bonnie et al. 2020; Cabinet Secretariat 2020). Research by Herranz-Pascual (Herranz-Pascual et al. 2019) suggests that regardless of nationality, people prefer open environments and engaging in communication within natural settings (Xu et al. 2021). Studies by Umberson (Umberson and Montez 2010) highlight that spending time with others can improve mental health. As young people grow, societal, educational, and familial demands often lead them to be less proactive in forming interpersonal relationships, particularly in Japan, Young people’s dependence on cell phones also seems to exacerbate this tendency (Zhao et al. 2023; Ito 2005). Another study found that stress impairs psychological and physiological health, but leisure experiences in green environments can ameliorate these negative emotional states (Orsega-Smith et al. 2004). Therefore, the experiences of interviewees suggest that environmental stress, job-hunting pressures, and the prolonged confinement during the pandemic have fostered a strong motivation to seek open natural environments for establishing human connections. The study reveals that many university juniors and seniors actively job-hunting exhibit a stronger willingness and motivation to move to rural areas in the future than students of other ages. This inclination may stem from the experiences during job-hunting activities, seemingly corroborated in past research (Afful-Broni 2012; Xu 2011).

Research indicates that urban children lacking natural activities and social interactions beyond family may face developmental challenges, such as depression and ADHD (Di Carmine and Berto 2020; Child Mind Institute 2023). Growing up in natural environments positively impacts health, with open, expansive settings aiding emotional expression and happiness, reducing depressive symptoms (Cameron-Faulkner et al. 2018). Many university students recall positive, joyful experiences from rural living or visits during childhood. Studies in Western countries reveal a tendency to move to rural areas after starting families. Although such statistics are rare in Japan, interviews suggest many young Japanese prefer raising children in rural settings, possibly influencing Japan’s low birth rate in aging society.

Many studies have found an increasing allure towards self-sufficient lifestyles, with Western countries embracing it earlier and Asian countries recently developing interest (Yoshida 2021). Research highlights that events like Japan’s 2011 earthquake and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic have reshaped young Japanese individuals’ perceptions of urban versus rural living, especially the trend of “escaping Tokyo” during the pandemic (He and Traphagan 2021). Interviews reveal a positive outlook towards rural communities, valuing self-sufficiency and independence from urban supply chains. The portrayal of rural life in media, exemplified by films, such as “Little Forest” and “The easy life in KAMUSARI”, romanticize rural living, influencing students’ willingness to engage in rural activities and volunteer in agriculture.

In Hanyu-shi, a region primarily zoned for agricultural revitalization, local government policies encourage land use for agriculture, offering learning support and subsidies for aspiring farmers (Hanyu-shi 2018). The preference for semi-urban areas like Hanyu-shi suggests a nuanced understanding of urban-rural dynamics. Unlike Western counter-urbanization studies, Japan’s research and case studies are limited (Dilley et al. 2022). However, this study finds an evolving mindset among young Japanese, shifting from economic necessity to seeking inner peace, deep human connections, self-sufficiency, and a natural upbringing for their children. These findings are notable for policymakers and urban planners in Japan, indicating a trust in the younger generation’s changing perspectives and values.

4.2. Reasons for Motive Weakening

Numerous studies suggest that frequent visits to rural areas deepen young people’s attachment and willingness to reside there (Buta et al. 2012; Riethmuller et al. 2021; Davis 2022). However, complex transportation and outdated infrastructure often hinder these opportunities, as reflected in this study (Milbourne and Kitchen 2014; Mao et al. 2023). Past research highlights the transportation difficulties faced by young people in China and Japan when traveling to rural areas and advocates for facilitating driver’s license examinations for university students to improve their access to rural areas (Mao et al. 2022). However, the enhancement of transportation and ongoing infrastructure development in rural areas demands significant financial and manpower investment. This presents a critical need for governmental intervention to allocate and develop essential resources (MOE 2015). The central theme of this study is how young people and young adults experience obstacles and opportunities in relation to their past, present and potential future in a rural area.

However, deeper social interaction, a motive for rural relocation, also has its drawbacks. Language barriers (Gordon 2019), particularly dialect differences between urban youth and rural locals, impede communication. In Japan, where maintaining appropriate social distance is crucial, overly close, and intrusive relations in rural settings can deter young people seeking tranquility (Ball 2009). Past research found Engaging youth in local activities can foster more active participation (Majee et al. 2020), but balancing interpersonal relationships and promoting standard Japanese and dialect education are also important aspects of Japanese social discourse from this research.

A major factor deterring rural relocation is the lack of job opportunities, as past research found that young Japanese opt for urban education and careers due to better prospects in cities (Naoko Hiromori 2018). Physical and skill requirements in rural jobs, coupled with higher urban salaries, further dissuade them (Masuda 2012). This study observes that the remote work model, which gained prominence during the pandemic, has influenced perceptions about post-pandemic work location flexibility. This shift may potentially facilitate the inclination of young individuals towards remote working in rural areas in the future.

Encouraging young people’s relocation to rural areas necessitates balancing opportunities between urban and rural settings. Previous studies suggest rural governments could foster collaborations with urban counterparts, providing incentives such as entrepreneurship subsidies, co-working spaces in rural areas, and travel allowances (Wang et al. 2022; Kupriianchik et al. 2019). These strategies, as revealed in interviews conducted for this study, aligns with sustainable development guidelines, and promotes active youth engagement in rural life. In addition to the local government policies in Hanyu-shi that promote agricultural land use and provide learning support, there is a pressing need to address the skill gap among potential young farmers. The provision of comprehensive agricultural training programs, akin to the Richmond Farm School in Metro Vancouver, could significantly enhance the appeal of rural migration (Kwantlen Polytechnic University 2024). Such programs are instrumental in building the necessary skills and confidence required for agricultural endeavors, which is an essential factor in the decision-making process for youth considering a move to rural areas. By funding skill-training programs, the Japanese government could better motivate city youths to move to the countryside, supporting community sustainability and growth.

The pandemic has increased young people’s willingness to experience rural life and consider future rural residency (González-Leonardo et al. 2022). Over a century after the Garden City movement (Edwards 1913), the balance between urban and rural living remains a pivotal consideration. This study could provide valuable insights for future research on sustainable rural development. The temporary tilt towards rural settings during the pandemic, owing to remote work possibilities, was short-lived, and as normalcy returned, urban settings reclaimed their allure (Martin 2021). In summary, these weakening motives offer insights for policymakers. Addressing them requires a holistic approach not limited to infrastructural upgrades or economic incentives. This goal is about reshaping perceptions, cultivating inclusivity, and assuring the younger generation that rural areas can harmoniously blend tranquility with opportunity. Finally, this study focuses on youths with prior rural experiences, which may limit the applicability of its findings to the broader youth population, especially those without any rural background. Future research should include youths with no rural exposure to gain a more holistic view of young people’s attitudes towards rural living. Additionally, exploring other rural revitalization strategies like international immigration, place branding, and municipal mergers is crucial. These elements could significantly impact rural development policies, especially in attracting young people to rural areas. Future research could investigate these aspects to provide a more nuanced understanding of rural revitalization in Japan.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reveals key motivations and deterrents influencing young individuals’ intentions to relocate to rural areas, particularly Hanyu-shi. The primary drivers include the desire for a tranquil lifestyle, emotional attachment stemming from childhood experiences, and aspirations for a nature-centric upbringing for future generations. Conversely, barriers such as inadequate transportation, limited job opportunities, and concerns over social integration and educational standards weaken these motives. The findings highlight a nuanced understanding of the factors shaping rural migration intentions among Japan’s youth.

This research offers valuable insights for policymakers and academia. For governmental authorities, understanding these motivations and challenges can inform the development of targeted strategies to encourage rural resettlement, particularly among the youth. Academically, the study contributes to the broader discourse on rural–urban dynamics, offering a contemporary perspective on counter-urbanization trends in Japan. The findings underscore the importance of considering both motivational drivers and practical barriers in formulating policies aimed at sustainable rural development and rejuvenation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M. and L.H.; methodology, Y.M.; software, Y.M.; validation, Y.M., L.H. and K.F.; formal analysis, Y.M.; investigation, Y.M.; resources, Y.M.; data curation, L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.; writing—review and editing, Y.M.; visualization, Y.M.; supervision, D.D.; project administration, Y.M. and D.D.; funding acquisition, K.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Compliance with the Helsinki Declaration: 1. My research is non-invasive and adheres to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. I obtained verbal consent from all participants before conducting the survey. 2. University Approval: The research was conducted with the permission of the university, which did not require any formal ethical approval documentation due to the nature of the study. 3. Ethical Committee Guidelines: According to the official ethical guidelines from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, my study is exempt from ethical approval as it does not involve medical research targeting individuals and ensures data protection and non-invasiveness. You can find more information here: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/shingi/2r985200000359ny-att/2r985200000359uq_1.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adevi, Anna A., and Fredrika Mårtensson. 2013. Stress Rehabilitation through Garden Therapy: The Garden as a Place in the Recovery from Stress. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 12: 230–37. [Google Scholar]

- Afful-Broni, Anthony. 2012. Relationship between Motivation and Job Performance at the University of Mines and Technology, Tarkwa, Ghana: Leadership Lessons. Creative Education 3: 309–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirhayim, Rashad. 2023. Place Attachment in the Context of Loss and Displacement: The Case of Syrian Immigrants in Esenyurt, Istanbul. Journal of Urban Affairs, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amare, Mulubrhan, Kibrom A. Abay, Channing Arndt, and Bekele Shiferaw. 2021. Youth Migration Decisions in Sub-Saharan Africa: Satellite-Based Empirical Evidence from Nigeria. Population and Development Review 47: 151–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, Sorensen. 2002. The Making of Urban Japan|Cities and Planning from Edo to the Twenty. London: Routledge. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203993927/making-urban-japan-andr%C3%A9-sorensen (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Bailey, Etienne, Patrick Devine-Wright, and Susana Batel. 2021. Emplacing Linked Lives: A Qualitative Approach to Understanding the Co-Evolution of Residential Mobility and Place Attachment Formation over Time. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 31: 515–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Richard. 2009. Social Distance in Japan: An Exploratory Study. Michigan Sociological Review 23: 105–12. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40958769 (accessed on 4 January 2024).

- Berry, Brian J. L. 1980. Urbanization and Counterurbanization in the United States. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 451: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokushu. 2018. Bokushu Homepage. Available online: https://www.bokushu.net/ (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Bonnie, Robert, Emily Pechar Diamond, and Elizabeth Rowe. 2020. Understanding Rural Attitudes toward the Environment and Conservation in America. Durham: Duke University. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buta, Natalia, Mark Brennan, and Stephen Holland. 2012. A Mixed-Methods Investigation of Community Attachment in Rural Romania. Journal of Rural Social Sciences 27: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office. 2023. NPO Portal Site:Non-Profit Organization Udokuseiko. Available online: https://www.npo-homepage.go.jp/npoportal/detail/011090400 (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Cabinet Secretariat. 2020. Available online: https://www.chisou.go.jp/sousei/pdf/ijuu_chousa_houkokusho_0515.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Cameron-Faulkner, Thea, Joanna Melville, and Merideth Gattis. 2018. Responding to Nature: Natural Environments Improve Parent-Child Communication. Journal of Environmental Psychology 59: 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Mind Institute. 2023. Why Kids Need to Spend Time in Nature. Available online: https://childmind.org/article/why-kids-need-to-spend-time-in-nature/ (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Corday, Chris. 2023. Japan Offers Families Tens of Thousands of Dollars to Say Goodbye to Tokyo. CBC. January 28. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/japan-tokyo-relocation-funding-1.6717312 (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Coventry, Peter A., JenniferV. E. Brown, Jodi Pervin, Sally Brabyn, Rachel Pateman, Josefien Breedvelt, Simon Gilbody, Rachel Stancliffe, Rosemary McEachan, and PiranC L. White. 2021. Nature-Based Outdoor Activities for Mental and Physical Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SSM-Population Health 16: 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmann, Nicholas, Jennifer Wolch, Pascale Joassart-Marcelli, Kim Reynolds, and Michael Jerrett. 2010. The active city? Disparities in provision of urban public recreation resources. Health Place 16: 431–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dana-Alina, U., Ngureanu, and U. Dănuț. 2021. Relevant Differences between Urban and Rural from the Perspective of Young People’s Lifestyle. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Relevant-Differences-between-Urban-and-Rural-from-Dana-Alina-Ngureanu/af88a63b5463680c696d0095296726a7145b2e34 (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Davis, Zach T. 2022. Not All Trails Are Straight: The Effects of Attachment on Rural Youth Residential Aspirations. Master’s thesis, University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong-Gierveld, Jenny, Theo G. van Tilburg, and Pearl A. Dykstra. 2006. Loneliness and Social Isolation. In The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 485–500. [Google Scholar]

- Di Carmine, Francesca, and Rita Berto. 2020. Contact with Nature Can Help ADHD Children to Cope with Their Symptoms. The State of the Evidence and Future Directions for Research. Visions for Sustainability 15: 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilley, Luke, Menelaos Gkartzios, and Tokumi Odagiri. 2022. Developing Counterurbanisation: Making Sense of Rural Mobility and Governance in Japan. Habitat International 125: 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Huimin. 2017. Place Attachment and Belonging among Educated Young Migrants and Returnees: The Case of Chaohu, China. Population, Space and Place 23: e1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eacott, Chelsea, and Christopher C. Sonn. 2006. Beyond Education and Employment: Exploring Youth Experiences of Their Communities, Place Attachment and Reasons for Migration. Rural Society 16: 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. Trystan. 1913. A Criticism of the Garden City Movement. The Town Planning Review 4: 150–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Romero, David, Cristina Varela Portela, and Ana Peixoto. 2023. Talking about Rural Environments, Education and Sustainability: Motives Positions and Practice of Grassroots Organizations. International Journal of Rural Development, Environment and Health Research 7: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Michael J. 2014. The Possibilities of Phenomenology for Organizational Research. Organizational Research Methods 17: 118–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Leonardo, Miguel, Francisco Rowe, and Alberto Fresolone-Caparrós. 2022. Rural Revival? The Rise in Internal Migration to Rural Areas during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Who Moved and Where? Journal of Rural Studies 96: 332–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, Michael D. E, Karmela Krleza-Jeric, and Trudo Lemmens. 2007. The Declaration of Helsinki. BMJ: British Medical Journal 335: 624–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Matthew J. 2019. Language Variation and Change in Rural Communities. Annual Review of Linguistics 5: 435–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. H. 2009. Rurality and Post-Rurality. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography. Edited by Rob Kitchin and Nigel Thrift. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 449–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanyu Shi. 2018. Available online: https://www.city.hanyu.lg.jp/docs/2018032600011/ (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Hanyu Shi. 2022. Hanyu Shi Outline: Location, Area, and Climate. Available online: https://www.city.hanyu.lg.jp/docs/2010070200024/ (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Hanyu Shi Municipal Intelligence. 2015. Available online: https://www.city.hanyu.lg.jp/docs/2014033100079/file_contents/2014033100079_www_city_hanyu_lg_jp_kurashi_madoguchi_kikaku_03_city_05_toukeihanyu_h25_doc_1.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Hanyu Shi, The 6th Hanyu Shi Comprehensive Development Plan. 2023. Cooperation and Culture_~Create a City Where People Can Live Together with the Community. Available online: https://www.city.hanyu.lg.jp/docs/2018032600011/file_contents/seisaku1.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2023).

- Hart, Kim. 2020. Why Coronavirus May Prompt Migration out of American Cities. Axios. April 30. Available online: https://www.axios.com/2020/04/30/coronavirus-migration-american-cities-survey (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- He, Lauren, and John W. Traphagan. 2021. A Preliminary Exploration of Attitudes about COVID-19 among a Group of Older People in Iwate Prefecture, Japan. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 36: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herranz-Pascual, Karmele, Itziar Aspuru, Ioseba Iraurgi, Álvaro Santander, Jose Luis Eguiguren, and Igone García. 2019. Going beyond Quietness: Determining the Emotionally Restorative Effect of Acoustic Environments in Urban Open Public Spaces. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero-Jáuregui, Cristina, and E. D. Concepción. 2023. Effects of Counter-Urbanization on Mediterranean Rural Landscapes. Landscape Ecology 38: 3695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, Shiro. 2019. Remain or Leave?: Attitudes of Residential Young Workers in Iide, Japan. Sociological Theory and Methods 34: 145–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hyassat, Mizyed, Nawaf Al-Zyoud, and Mu’tasem Al-Masa’deh. 2023. Mothering a Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Social Sciences 12: 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, Masae, and Wakako Fujii. 2004. Reseach on the Consciousness That Young People Possess Regarding Agriculture and Its products—The Importance of Their Experience and Study Involved in the Practice of Farming. Bulletin of Mimasaka University 37: 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Mizuko. 2005. Mobile Phones, Japanese Youth, and the Re-Placement of Social Contact. In Computer Supported Cooperative Work. London: Springer, pp. 131–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izuta, Giido, Megumi Nakagawa, Tomoko Nishikawa, and Yuka Sato. 2016. Modeling the Relationships between Depopulation Phenomenon in Rural Areas Due to Human Translation to Big Cities and Young People’s Values. Yamagata Prefectural Public University Corporation Academic Repository 52: 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Cabinet Meeting. 2023. Comprehensive Strategy for the Digital Rural City National Concept. Available online: https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/digital_denen/pdf/20231226honbun.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- John, Gerzema. 2020. Harris Poll COVID-19 Tracker Wave 8. Harris Poll COVID-19 Tracker Wave 8. April 22. Available online: https://theharrispoll.com/briefs/covid-19-tracker-wave-8/ (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Karasawa, Moeri, and Jessie Yeung. 2023. Japan’s Population Drops by Half a Million in 2022. CNN. April 13. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2023/04/13/asia/japan-population-decline-record-drop-intl-hnk/index.html (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Klien, Susanne. 2020. Urban Migrants in Rural Japan: Between Agency and Anomie in a Post-Growth Society. Albany: Suny Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koay, Way Inn, and Denise Dillon. 2020. Community Gardening: Stress, Well-Being, and Resilience Potentials. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokuro Ichimasa. 2022. The Canon Institute for Global Studies: The Number of Births May Fall below 500,000, 20 Years ahead of the Government’s Projection—Professor Kazumasa Oguro’s Half a Step Ahead in the Economy Classroom. Available online: https://cigs.canon/article/20220617_6835.html (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Kuh, George D., Jillian L. Kinzie, Jennifer A. Buckley, Brian K. Bridges, and John C. Hayek. 2006. What Matters to Student Success: A Review of the Literature. 8 vols. Washington, DC: National Postsecondary Education Cooperative. [Google Scholar]

- Kupriianchik, Iryna, Andriy Dorosh, and Viktoriia Saliuta. 2019. Factors of Impact on Rural Green Tourism Development as a Small Entrepreneurship in Ukraine. Environmental Economics and Sustainable Development 6: 100–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwantlen Polytechnic University. 2024. Richmond Farm School 2024. Available online: https://www.kpu.ca/rfs/program-details (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Liu, Yansui, and Yuheng Li. 2017. Revitalize the World’s Countryside. Nature 548: 275–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomas, Michael J., Eunice Ayodeji, and Philip Brown. 2021. Experiences of Place Attachment and Mental Wellbeing in the Context of Urban Regeneration. Health & Place 70: 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Shixian, Jing Xie, and Katsunori Furuya. 2021. ‘We Need Such a Space’: Residents’ Motives for Visiting Urban Green Spaces during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 13: 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAFF. 2018. Rural Development Bureau, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries: Building the Next Generation of Agriculture and Rural Communities in Light of Changing Social Conditions. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/council/seisaku/nousin/bukai/H30-01/attach/pdf/index-18.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- MAFF. 2020. Previous Basic Plan for Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas—Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/wpaper/w_maff/r1/r1_h/trend/part1/chap0/c0_1_01.html (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- MAFF. 2022. Farm Stay Fanbassador Piko Taro Supports ‘Farm Stay’ with His Song! MAFF Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/press/nousin/kouryu/220113.html (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- MAFF. 2023. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/nousin/hotline/attach/pdf/index-97.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Majee, Wilson, Adaobi Anakwe, and Karien Jooste. 2020. Youth and Young Adults These Days: Perceptions of Community Resources and Factors Associated with Rural Community Engagement. Journal of Rural Social Sciences 35: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Yingming, Lei He, and Katsunori Furuya. 2022. ‘How We Understand Our Place’: A Study of Japanese University Student’s Place Attachment and Desire to Live to Rural Areas. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 1092: 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Yingming, Lei He, Dibyanti Danniswari, and Katsunori Furuya. 2023. College Students’ Perceptions of and Place Attachment to Rural Areas: Case Study of Japan and China. Youth 3: 737–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Alex K. T. 2021. COVID-19 Was Expected to Spur a Remote-Work Revolution in Japan. What Happened? The Japan Times. September 19. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/09/19/business/pandemic-japan-remote-work-failure/ (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Masuda, Jin. 2012. Permanent Part-Time Youth and Hope. Japanese Sociological Review 63: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbourne, Paul, and Lawrence Kitchen. 2014. Rural Mobilities: Connecting Movement and Fixity in Rural Places. Journal of Rural Studies 34: 326–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2020. An Overview of Population Vital Statistics (Confirmed) for the Year 2020. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/kakutei20/index.html (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Ministry of the Environment, White Paper on the Environment. 2015. Chapter 3: Sustainable Regional Development to Help Solve Local Economic and Social Issues. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/policy/hakusyo/h27/html/hj15010301.html (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- MLIT. 2002. White Paper on Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Available online: https://data.e-gov.go.jp/data/dataset/mlit_20201105_0065/resource/26052af8-9b43-433d-a4b3-970a34f3c0d8 (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Moganedi, Shonisane Emily, and Tshimangadzo Selina Mudau. 2024. Stigma and Mental Well-Being among Teenage Mothers in the Rural Areas of Makhado, Limpopo Province. Social Sciences 13: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, Hiroshi. 1988. On the Phenomenon of Population Turnaround or ‘Counterurbanization’. Geographical Review of Japa,. Ser. A, Chirigaku Hyoron 61: 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Naoko Hiromori. 2018. An Exploratory Study on Regional Mobility, Retention, and Career Choice of Young People in Rural Areas: Workplace Choice Based on Interviews with University Students of Social Work. Aomori University of Health and Welfare 18: 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, Mototsugu. 2023. Rural Development in Japan. In Sustainable Development Disciplines for Society: Breaking Down the 5Ps—People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnerships. Edited by Shujiro Urata, Ken-Ichi Akao and Ayu Washizu. Sustainable Development Goals Series; Singapore: Springer Nature, pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odagiri, Tokumi. 2013. Rural Innovation Theory and Supporters for Rural Regeneration. Journal of Rural Planning 32: 384–87. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD, Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2020. Policy Implications of Coronavirus Crisis for Rural Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/policy-implications-of-coronavirus-crisis-for-rural-development-6b9d189a/ (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Orsega-Smith, Elizabeth, Andrew J. Mowen, Laura L. Payne, and Geoffrey Godbey. 2004. The Interaction of Stress and Park Use on Psycho-Physiological Health in Older Adults. Journal of Leisure Research 36: 232–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peen, Jaap, Robert A. Schoevers, Aartjan T. Beekman, and Jack Dekker. 2010. The Current Status of Urban-rural Differences in Psychiatric Disorders. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 121: 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, Lorna J., and Mark Shucksmith. 2003. Conceptualizing Social Exclusion in Rural Britain. European Planning Studies 11: 461–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Martin, Darren Smith, Hannah Brooking, and Mara Duer. 2021. Re-Placing Displacement in Gentrification Studies: Temporality and Multi-Dimensionality in Rural Gentrification Displacement. Geoforum 118: 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]