Slow Work: The Mainstream Concept

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Emergence of the Slow Movement

2.2. Slow Submovements and Empirical Evidence

2.3. Emergence of the Slow Work Concept

2.4. Similar Concepts

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Method

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Organisational Culture (Values and Principles)

4.2. Organisational Practices

4.3. Individual Characteristics

4.4. Implications for People

4.5. Implications for Organisations

4.6. Antithesis

4.7. Balance/Respect Rhythms and Limits

4.8. Humanisation

4.9. Recovery

4.10. Thinking Time

4.11. Quality

4.12. Purpose

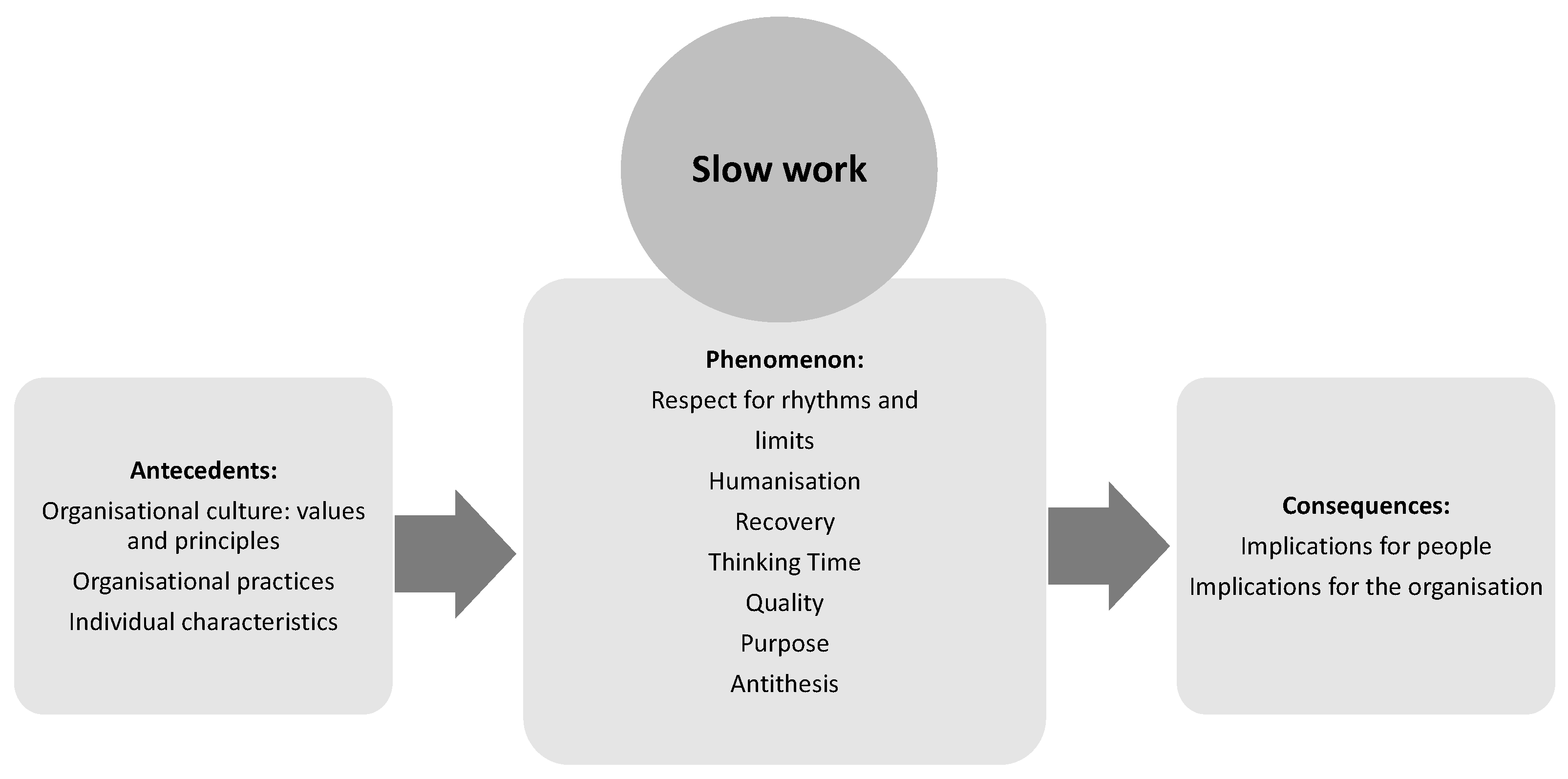

4.13. Development of Theory for Slow Work

5. Discussion

Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allan, Blake A., Cassondra Batz-Barbarich, Haley M. Sterling, and Louis Tay. 2019. Outcomes of Meaningful Work: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Management Studies 56: 500–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Tammy D., Ryan C. Johnson, Kaitlin M. Kiburz, and Kristen M. Shockley. 2013. Work–family conflict and flexible work arrangements: Deconstructing flexibility. Personnel Psychology 66: 345–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, Sunil, and David J. Aspelin. 1998. The overtime rebellion: Symptom of a bigger problem? Academy of Management Perspectives 12: 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, Susan. 2015. Slow cities. In Theme Cities: Solutions for Urban Problems. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 563–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bluedorn, Allen C., and Robert B. Denhardt. 1988. Time and organizations. Journal of Management 14: 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, Marta. 2016. Evolution of the slow living concept within the models of sustainable communities. Futures 80: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, Tarquin. 2007. Cultivating a leisurely life in a culture of crowded time: Rethinking the work/leisure dichotomy. World Leisure Journal 49: 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, Harry. 1974. Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York: Monthly Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Ronald J. 2009. Working to live or living to work: Should individuals or organizations care? Journal of Business Ethics 84: 167–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, Abraham, Jane E. Dutton, and Ashley E. Hardin. 2015. Respect as an engine for new ideas: Linking respectful engagement, relational information processing and creativity among employees and teams. Human Relations 68: 1021–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consiglio, Chiara, Nicoletta Massa, Valentina Sommovigo, and Luigi Fusco. 2023. Techno-Stress Creators, Burnout and Psychological Health among Remote Workers during the Pandemic: The Moderating Role of E-Work Self-Efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 7051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Tom. 1993. Stress Research and Stress Management: Putting Theory to Work. Bootle: Health and Safety Executive Books. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, Lyn. 2016. Contemporary Motherhood: The Impact of Children on Adult Time. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, Anne, and Ann Dupuis. 2004. Work-life balance?: Insights from non-standard work. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations 29: 21. Available online: http://www.oit.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---actrav/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_161353.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Arnold B. Bakker, Sabine Sonnentag, and Clive J. Fullagar. 2012 Work-related flow and energy at work and at home: A study on the role of daily recovery. Journal of No Organizational Behaviour 33: 276–95. [CrossRef]

- Dich, Nadya, Rikke Lund, Åse Marie Hansen, and Naja Hulvej Rod. 2019. Mental and physical health effects of meaningful work and rewarding family responsibilities. PLoS ONE 14: e0214916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, Janet E., Les M. Lumsdon, and Derek Robbins. 2011. Slow travel: Issues for tourism and climate change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 19: 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhefnawy, Nader. 2022. Contextualizing the Great Resignation (A Follow-Up to ‘Are Attitudes to Work Changing’): A Note. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound, and European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). 2014. Psychosocial Risks in Europe: Prevalence and Strategies for Prevention. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound, Greet Vermeylen, Gijs van Houten, and Isabelle Niedhammer. 2012. 5th European Working Conditions Survey: Overview Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). 2014. Calculating the Cost of Work-Related Stress and Psychosocial Risks. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c8328fa1-519b-4f29-aa7b-fd80cffc18cb (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA). 2019. Third European Survey of Enterprises on New and Emerging (ESENER-3). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/third-european-survey-enterprises-new-and-emerging-risks-esener-3 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. 2002. Guidance on Work-Related Stress: Spice of Life or Kiss of Death. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Communities. Available online: https://www.stress.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Guidance2520on2520work-realted2520stress.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Farelnik, Eliza, and Agnieszka Stanowicka. 2016. Smart city, slow city and smart slow city as development models of modern cities. Olsztyn Economic Journal 11: 359–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, Gregory J. 1997. Quantity, quality, and depth of research as influences on scientific eminence: Is quantity most important? Creativity Research Journal 10: 325–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Kate. 2010. Slow fashion: An invitation for systems change. Fashion Practice 2: 259–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullagar, Simone, Kevin Markwell, and Erica Wilson. 2012. Slow Tourism: Experiences and Mobilities. Bristol: Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Graham. 2008. Analyzing Qualitative Data. New York: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. London: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2014. A Sociedade do Cansaço. Lisboa: Relógio D’Água. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken, Paul, Amory B. Lovins, and L. Hunter Lovins. 2013. Natural Capitalism: The Next Industrial Revolution. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, Sine, Peter Robinson, and Ghislaine Povey. 2011. Slow food, slow cities and slow tourism. In Research Themes for Tourism. pp. 114–27. Available online: https://books.google.pt/books?hl=en&lr=&id=I3M6MdvntzMC&oi=fnd&pg=PA114&dq=Slow+food,+slow+cities+and+slow+tourism.+Research+Themes+for+Tourism&ots=hUOa9aYB2Z&sig=AjvHyALbgwYycaj7qVcgOUQNPDU&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=Slow%20food%2C%20slow%20cities%20and%20slow%20tourism.%20Research%20Themes%20for%20Tourism&f=false (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Hoel, Helge, Kate Sparks, and Cary L. Cooper. 2001. The cost of violence/stress at work and the benefits of a violence/stress-free working environment. Geneva: International Labour Organization 81: 327–37. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-cost-of-violence%2Fstress-at-work-and-the-of-a-Hoel/cc8a1de0c987008e1422ca91b1f9cdaf6f733ccd?p2df (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Honoré, Carl. 2004. In Praise of Slow: How a Worldwide Movement Is Challenging the Cult of Speed. London: Orion Books. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2019. Rules of the Game: An Introduction to the Standards Related Activities of the International Labour Organisation. Geneva: International Labour Office. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---normes/documents/publication/wcms_672549.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Jaskiewicz, Wanda, and Kate Tulenko. 2012. Increasing community health worker productivity and effectiveness: A review of the influence of the work environment. Human Resources for Health 10: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kalliath, Thomas, and Paula Brough. 2008. Work–life balance: A review of the meaning of the balance construct. Journal of Management & Organization 14: 323–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Janice R., and Joseph E. McGrath. 1985. Effects of time limits and task types on task performance and interaction of four-person groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49: 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Minseo, and Terry A. Beehr. 2018. Organization-Based Self-Esteem and Meaningful Work Mediate Effects of Empowering Leadership on Employee Behaviors and Well-Being. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 25: 385–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, David. 2019. Taking it day-by-day: An exploratory study of adult perspectives on slow living in an urban setting. Annals of Leisure Research 22: 463–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M. Asher, Richard P. Larrick, and Jack B. Soll. 2020. Comparing fast thinking and slow thinking: The relative benefits of interventions, individual differences, and inferential rules. Judgment and Decision Making 15: 660–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lease, Suzanne H., Christina L. Ingram, and Emily L. Brown. 2019. Stress and Health Outcomes: Do Meaningful Work and Physical Activity Help? Journal of Career Development 46: 251–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legere, Alisha, and Jiyun Kang. 2020. The role of self-concept in shaping sustainable consumption: A model of slow fashion. Journal of Cleaner Production 258: 120699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Masurier, Megan. 2015. What is slow journalism? Journalism Practice 9: 138–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Suzan. 2003. Flexible working arrangements: Implementation, outcomes, and management. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 18: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips-Wiersma, Marjolein, Sarah Wright, and Bryan Dik. 2016. Meaningful work: Differences among blue-, pink-, and white-collar occupations. Career Development International 21: 534–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludden, Geke D. S., and Linda Meekhof. 2016. Slowing down: Introducing calm persuasive technology to increase wellbeing at work. Paper presented at 28th Australian Conference on Computer-Human Interaction, Tasmania, Australia, November 29–December 2; pp. 435–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, Mara. 2008. Cittáslow: Producing slowness against the fast life. Space and Polity 12: 135–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Margaret. 2014. The slow university: Work, time and well-being. In Forum: Qualitative Social Research. Heslington: The University of York. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osbaldiston, Nick. 2013. Culture of the Slow: Social Deceleration in an Accelerated World. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Owens, Brian. 2013. Long-term research: Slow science. Nature News 495: 300–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panigrahi, C. M. Ashok. 2016. Managing stress at workplace. Journal of Management Research and Analysis 3: 154–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkins, Wendy. 2004. Out of time: Fast subjects and slow living. Time & Society 13: 363–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkins, Wendy, and Geoffrey Craig. 2006. Slow Living. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, John, and Erna Perry. 2015. Contemporary Society: An Introduction to Social Science. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Lawrence H., Edward J. O’Connor, Abdullah Pooyan, and James C. Quick. 1984. The Relationship between Time Pressure and Performance: A Field Test of Parkinson’s Law. Journal of Occupational Behaviour 5: 293–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, Carlo. 2003. Slow Food: The Case for Taste. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrini, Carlo. 2007. Slow Food. In The Architect, the Cook and the Good Taste. Basel: Birkhäuser. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, Sarah. 2008. Sense and sustainability: The case of the Slow City movement. Local Environment 13: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portuguese Psychologists’ Order. 2020. Prosperity and Sustainability of Organisations. Report on the Cost of Stress and Psychological Health Problems at Work in Portugal. Available online: https://www.ordemdospsicologos.pt/ficheiros/documentos/relatorio_riscos_psicossociais.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Prem, Roman, Sandra Ohly, Bettina Kubicek, and Christian Korunka. 2017. Thriving on challenge stressors? Exploring time pressure and learning demands as antecedents of thriving at work. Journal of Organizational Behavior 38: 108–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, Barbara L., and Mary Anne M. Hyland. 2002. Role conflict and flexible work arrangements: The effects on applicant attraction. Personnel Psychology 55: 111–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, Renate, and Antje Triemer. 2004. Overtime in relation to blood pressure and mood during work, leisure, and night time. Social Indicators Research 67: 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, Helen, Philip J. O’Connell, and Frances McGinnity. 2009. The impact of flexible working arrangements on work–life conflict and work pressure in Ireland. Gender, Work & Organization 16: 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, Brigid. 2019. Preventing Busyness from Becoming Burnout. Harvard Business Review Digital, 2–7. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/04/preventing-busyness-from-becoming-burnout (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Sheather, Julian, and Dubhfeasa Slattery. 2021. The great resignation-how do we support and retain staff already stretched to their limit? BMJ 375: n2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloman, Steven A. 1996. The empirical case for two systems of reasoning. Psychological Bulletin 119: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, Sabine, and Eva Natter. 2004. Flight attendants daily recovery from work: Is there no place like home? International Journal of Stress Management 11: 366–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnentag, Sabine, and Ute-Vera Bayer. 2005. Switching off mentally: Predictors and consequences of psychological detachment from work during off-job time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 10: 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stearns, Peter N. 2020. The Industrial Revolution in World History. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, John Paul, Emily Heaphy, and Jane E. Dutton. 2012. High-quality Connections. In The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship. Edited by Kim S. Cameron and Gretchen M. Spreitzer. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. New York: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sull, Donald, Charles Sull, and Ben Zwei. 2022. Toxic Culture Is Driving the Great Resignation. MIT Sloan Management Review 63: 1–9. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/toxic-culture-is-driving-thegreat-resignation/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Tong, Ling. 2018. Relationship between meaningful work and job performance in nurses. International Journal of Nursing Practice 24: e12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakakis, Nick N. 2018. Slow philosophy. The Heythrop Journal 59: 221–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bommel, Koen, and André Spicer. 2011. Hail the snail: Hegemonic struggles in the slow food movement. Organization Studies 32: 1717–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Slow Submovements | Assumptions |

|---|---|

| Slow Food (Petrini 2003; Van Bommel and Spicer 2011) |

|

| Slow Living (Botta 2016; Lamb 2019; Parkins 2004; Parkins and Craig 2006) |

|

| Slow Cities (Ball 2015; Farelnik and Stanowicka 2016; Miele 2008; Pink 2008) |

|

| Slow Tourism (Heitmann et al. 2011; Fullagar et al. 2012) |

|

| Slow Travel (Dickinson et al. 2011) |

|

| Slow Journalism (Le Masurier 2015) |

|

| Slow Fashion (Fletcher 2010; Legere and Kang 2020) |

|

| Slow University (O’Neill 2014) |

|

| Slow Science (Owens 2013) |

|

| Slow Philosophy (Trakakis 2018) |

|

| Slow Thinking (Lawson et al. 2020; Sloman 1996) |

|

| Participant | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 48 | 46 | 44 | 50 | 44 | 44 | 55 | 39 | 38 | 43 | 49 | 44 |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female | Female | Female | Female |

| Role | Operations Director | Technical Director + Human Resources Director | Senior Project Manager HR Processes | Group People Director | CEO | Chief Human Resources Office | Manager/Co-founder/Chief Culture Officer (CCO) | Head of Patents | Quality & Agility Department Manager | Manager | Talent Lead | Learning & Development Director |

| Years of experience in leadership positions | +10 years | +20 years | +10 years | +15 years | 6 years | +10 years | +30 years | 5 years | 8 years | 7 years | 7 years | +5 years |

| Industry in which it operates | Banking and Finance | Social sector | Food Retail and Farming | Business & facilities services | Building and Construction | Customer care & Technical support | IT | Intellectual Property | IT | IT | Telecommunications | Mobility and Parking |

| No. of employees in the organisation | 6244 (PT) 378 (Operations Dep.) | 155 (PT) | 35,000 (PT) 120,000 (Global) | 20,000 (PT) | 77 (PT) | 12,400 (PT) | 230 (PT) | 70 (PT) | 1000 (PT) | 550 (PT) 720 (Global) | 1400 (PT) | 800 (PT) |

| Main Topics | General Purpose | Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Slow Work Phenomenon | Identify and understand slow work |

|

| Slow Work Antecedents | Identify and understand the organisational and individual resources and vulnerabilities that influence slow work |

|

| Consequences of Slow Work | Identify and understand the implications of slow work for the organisation and employees |

|

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Antecedents | Organisational culture (values and principles) Organisational practices Individual characteristics |

| Consequences | Implications for people Implications for the organisations |

| Phenomenon | Respect for rhythms and limits Humanisation Recovery Thinking time Quality Purpose Antithesis |

| Subcategory | Systematisation (Open Coding) | Participant Reports—Examples | Analysis: Systematisation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational culture (values and principles) | Aspects of the values and principles that are valued in an organisational culture that follows slow work were noted | “It has to be a culture focused on people, on people well-being” (P7) “Respecting individuality and the rhythms that each person will have to develop their work” (P9) “The humanisation of work. Individualisation in the sense of realising that each person is unique … humanisation without doubt, and that alone is already immense” (P10) “It has to be an innovative company, it has to have the character of innovation and be disruptive in the face of what happens, have the courage to say that you work differently here” (P12) |

|

| Organisational practices | Aspects of organisational practices that are aligned with slow work were noted | “In slow work it is much more important to focus on work goals than on the number of hours worked” (P7) “An important practice is downtime to have reflection times on work. Reflection times can make all the difference in teams” (P2) |

|

| Individual characteristics | Aspects of the individual characteristics best suited for slow work were noted | “It takes a process of self-awareness for people to know when they work best, or when they are in need of rest. They need to have that self-awareness” (P9) |

|

| Subcategory | Systematisation (Open Coding) | Participant Reports—Examples | Analysis: Systematisation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implications for people | Aspects of the consequences of slow work for workers were noted | “This way of working will always enhance well-being” (P9) “The slow way of working surely has positive implications on performance, and quality.” (P1) |

|

| Implications for the organisation | Aspects of the consequences of slow work for organisations were noted | “Productivity will be affected in a positive way.” (P1) “It results in a higher quality of work.” (P4) “If the workers are happier and more aware of what they do, the organisation is also more lean, more productive, and is also more sustainable” (P3) |

|

| Subcategory | Systematisation (Open Coding) | Participant Reports—Examples | Analysis: Systematisation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respect for rhythms and limits | Aspects of respecting the workers’ individual rhythms and the healthy balance between a worker and his/her work tasks were noted | “A balance between what the organisation needs and what the person can give” (P3) |

|

| Humanisation | Aspects of respecting the human side of the worker were noted | “workers want respect, they want flexibility, and they want fair value for their work.” (P10) |

|

| Recovery | Aspects of workers’ needs to stop, rest, and recover were noted | “Recovery times are important for the slow work, but the type of recovery time needed will vary from individual to individual.” (P6) |

|

| Thinking time | Aspects of the importance of reflecting and taking time to focus on the work goals were noted | “The quality of work, the results of our work would have much to gain from this calm and reflection, from doing things with thinking”(P2) |

|

| Quality | Aspects of what is important to achieve in organisational goals and results were noted (quality vs. quantity) | “Always prioritize quality over quantity, because I believe that qualitative goals are more sustainable and lasting than quantitative ones.” (P3) |

|

| Purpose | Aspects of motivations and what gives meaning to the work were noted | “It’s respecting the interests and motivations of the workers, promoting this interaction and connection between people, which is so salutary. The focus is no longer on productivity and what has to be done, so we have space for creativity, which can then result in productivity.” (P11) |

|

| Antithesis | Aspects of what slow work is not were noted | “I compare being too busy a lot to consumerism, we seem to want to have more, and do more, and being too busy time is almost like a flag to show that we have value.” (P9) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silvestre, M.J.; Gonçalves, S.P.; Velez, M.J. Slow Work: The Mainstream Concept. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13030178

Silvestre MJ, Gonçalves SP, Velez MJ. Slow Work: The Mainstream Concept. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(3):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13030178

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilvestre, Maria João, Sónia P. Gonçalves, and Maria João Velez. 2024. "Slow Work: The Mainstream Concept" Social Sciences 13, no. 3: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13030178

APA StyleSilvestre, M. J., Gonçalves, S. P., & Velez, M. J. (2024). Slow Work: The Mainstream Concept. Social Sciences, 13(3), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13030178