When Women Ask, Does Curiosity Help?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Social Roles, Negotiation, and Curiosity

2.1. Social Roles

2.2. Gender Differences in Negotiations

2.3. Negotiating with Curiosity

3. Current Studies

4. Study 1

4.1. Materials and Method

4.1.1. Participants and Design

4.1.2. Procedure

4.1.3. Measures

4.2. Results

4.3. Discussion

5. Study 2

5.1. Materials and Method

5.1.1. Participants and Design

5.1.2. Procedure

5.1.3. Measures

5.2. Results

5.3. Discussion

6. Study 3

6.1. Materials and Method

Research shows that approaching a negotiation like this with curiosity can be a rewarding and effective strategy. Sure, think about what you want, but then when you go into the meeting, just be curious. Ask some questions so you can better understand your employer’s perspective and interests. (e.g., Would you be open to talking with me about my compensation?) Then once you’re ready to ask for what you want, you will be more likely to get what you are asking for.

Research shows that being direct can be a rewarding and effective strategy. Sure, think about what you want, but when you go into the meeting, negotiate directly with your supervisor. Ask directly for what you consider good pay and tell your expectations to your employer (e.g., I would like to be paid a reasonable wage for internship hours). The more you convey your expectations of good pay, the more likely it is that you will get better pay for your internship.

6.2. Measures

6.3. Results

6.4. Discussion

7. General Discussion

7.1. Implications and Contributions

7.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Study 1

Imagine you are the Food & Beverage Director for the Elliot Hotel in Ithaca, NY. You stepped into this position six months ago under a mandate to increase the cost-effectiveness of the hotel’s purchasing practices.

The hotel has been in search of a new coffee supplier after the current vendor raised prices in the middle of the contract. You recently set up a meeting with the East Coast Vice President of Sales for Truman Coffee after conducting a blind taste test of multiple coffee brands. Truman Coffee far surpassed other brands, with tasters preferring Truman Coffee over your current vendor by a margin of 3 to 1.

Truman Coffee also follows a “fair trade” policy which is appealing to the stakeholders of the hotel. However, Truman Coffee’s bid asks a much higher price than your current vendor. You are aware Truman Coffee is a superior product, but cost-cutting is a priority for the Hotel and a responsibility of your position.

You set up a meeting with the VP of Sales to negotiate the price of the contract. You have never met the VP of Sales for Truman Coffee, but colleagues have told you that Truman salespeople earn a commission for every cent above their minimum acceptable price, resulting in a personal bonus payment directly impacting their salary. You have heard that $7.25 is their minimum acceptable price.

While your boss has authorized you to pay as much as $7.40 per pound, and you would like to get as close to $7.25 as possible knowing the salesperson will negotiate for a higher price in order to receive an additional commission payment.

Emma or Mike: Hi! I’m curious…what are you looking for in a coffee supplier?

You: I am looking for fair trade practices and good coffee

Emma or Mike: Great to hear. Can you tell me more about the fair trade practices you’re looking for?

You: We hope to buy from a company that pays their employees fairly, gets their product in ethical practices and follows the terms of the contract.

Emma or Mike: That sounds very reasonable. I understand that you value sustainable practices and we can definitely deliver that. We pay our coffee growers a fair living wage.

You: That is great to hear. We are very hopeful to work with you. I understand your bid price is $7.94. Are you willing to negotiate that price?

Emma or Mike: You said that price also matters to you. I can give you a fair price but that will also reflect the fair wages we pay our workers. We can come down a bit

You: Great. I have a friend who works with the Colonial Williamsburg and from my understanding, they pay $6.95 per pound. Now, I know they have been a buyer for a longer time, so are you willing to start selling to us for $7.00?

Emma or Mike: Love that you’re bringing up one of our favorite customers. They are local though, so we don’t have to pay them shipping prices. We can offer you 7.60.

You: I understand the local delivery difference, but I believe we can offer your company more publicity in the hotel. Our hotel is visited by a wider range of people than Williamsburg, so we can generate more potential clients for you. Because we would be generating you more publicity, can you do $7.30?

Emma or Mike: We do love publicity (and students!) We could offer you 7.50 I’m curious. Is there anything that is important to you that I should know?

You: That’s great to hear. Our hotel’s close proximity to the Cornell campus and serving their students and faculty is another important value for us. The most we would be willing to buy for is $7.40. How does that sound?

Emma or Mike: I can do that for you

Emma or Mike: Hey

You: Hello!

Emma or Mike: We offer great coffee

You: So I see that you have offered 7.94 as your original bid price…let’s discuss through this!

Emma or Mike: I can offer 7.60/lb

You: My current provider is $6.00 so that’s still a little too high for me

Emma or Mike: let me offer you a price of 7.40/lbwe have sustainable practices and we don’t change our prices during the contract

You: I know from a friend that you are providing Colonial Williamsburg at $6.95

Can we get a little bit closer to that?

Emma or Mike: they buy more. 100,0007.40 is my best price

You: How about $7.20 to meet in the middle

Emma or Mike: Lets make a deal at 7.40Our coffee is really premium

You: I understand but at $1.40 over my current provider seems a little steep.$7.30?

Emma or Mike: we have sustainable practices and guaranteed fixed rate7.40 is my best price

You: That is also important to me.Are you sure that is the lowest you can go?Not even $7.35?

Emma or Mike: yes. 7.40 is my best price. our coffee is premium and sustainable

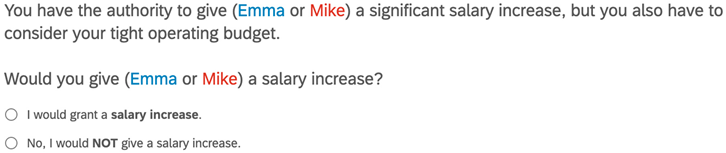

Appendix B. Study 2

Imagine that you are a supervisor and will engage in a performance review conversation with one of your employees, (Emma or Mike). (Emma or Mike) joined your team a few years ago. (She’s/He’s) been instrumental to delivering on the team’s key projects and quickly become an important part of the team. You are pleased with (her/his) performance and will deliver (her/his) annual performance feedback soon. While you can discuss (her/his) salary and give (her/him) a salary increase this year, you haven’t planned to offer it.

(Emma or Mike) comes into your office to discuss the performance feedback. During this session, you review (her/his) excellent progress on key tasks and (her/his) contributions to the team. You also set some goals for next year that involve taking on additional responsibilities on the company’s new initiatives.

After your review, [Mike/Emma] responds:

| No Ask | Curious Ask | Direct Ask |

| Mike/Emma: Thanks for taking the time to give me performance feedback. The feedback you provided is very clear to me. I am flexible, I could take on additional responsibilities next year to develop my skillset. | Mike/Emma: Thanks for taking the time to give me performance feedback. The feedback you provided is very clear to me. I am flexible, I could take on additional responsibilities next year to develop my skillset. | Mike/Emma: Thanks for taking the time to give me performance feedback. The feedback you provided is very clear to me. I am flexible, I could take on additional responsibilities next year to develop my skillset. |

| Then, you tell him/her that you could end the session if s/he has no questions, to which Mike/Emma responds: | Then, you tell him/her that you could end the session if s/he has no questions, to which Mike/Emma responds: | Then, you tell him/her that you could end the session if s/he has no questions, to which Mike/Emma responds: |

| Mike/Emma: I don’t have any additional questions. [the meeting ends] | Mike/Emma: I am also interested in discussing my salary… Would you be open to talking with me about a salary increase? I am interested in understanding how performance evaluations are linked to salary increases. | Mike/Emma: What was not clear, however, was whether I will be receiving a salary increase. Given my performance, I think I deserve a salary increase. |

| You don’t immediately respond to Mike/Emma’s request and Mike/Emma continues: | You don’t immediately respond to Mike/Emma’s request and Mike/Emma continues: | |

| Mike/Emma: I feel good about the work I have done and am glad to hear you have been pleased with my performance. I understand we may have different perspectives and I want to hear yours. I think I should be paid at the top of the salary range for my position given my high performance and the fact that I will be taking on additional responsibilities. I am curious to hear whether you agree or have a different perspective. | Mike/Emma: I feel good about the work I have done and am glad to hear you have been pleased with my performance. I think I should be paid at the top of the salary range for my position given my high performance and the fact that I will be taking additional responsibilities. This is really important to me; I think I deserve it. | |

| You explain your thinking and then ask Mike/Emma to continue discussing his/her expectations with you. S/He responds: | You explain your thinking and then ask Mike/Emma to continue discussing his/her expectations with you. S/He responds: | |

| Mike/Emma: I understand your constraints related to salary increases, as well as your expectations. I am thinking of something in the 25–30% of salary range. Salary increases may not be standard in my position, but given my excellent performance and additional responsibilities, I’d like to hear your thoughts on whether that would make me eligible to receive one. | Mike/Emma: I am thinking of something in the 25–30% of the salary range. Not doubling my salary or anything. Salary increases may not be standard in my position, but listen, I promise you I’ll earn it. |

| 1. |  |

| 2. |  |

Appendix C. Study 3

Imagine you have been offered a summer internship with a reputable company in your field. Given your interests, qualifications, and skills, this company is a great fit for you. You think that this experience will help you broaden and improve your skill set, likely making you more marketable when you graduate. You are also excited as you see yourself contributing to the company’s operations and helping the people you work with in their day-to-day operations.

You received a call from your prospective supervisor confirming your offer. The supervisor wants to meet with you to discuss the job, including your responsibilities and company expectations.

There has been no mention of pay and it’s not clear whether this company pays for internship hours. If they do, you have no idea what an appropriate range would be.

You will have a meeting with your supervisor soon and you are considering taking this opportunity to negotiate an hourly pay.

Research shows that approaching a negotiation like this with curiosity can be a rewarding and effective strategy. Sure, think about what you want, but then when you go into the meeting, just be curious. Ask some questions so you can better understand your employer’s perspective and interests. (e.g., Would you be open to talking with me about my compensation?) Then once you’re ready to ask for what you want, you will be more likely to get what you are asking for.

Research shows that being direct can be a rewarding and effective strategy. Sure, think about what you want, but when you go into the meeting, negotiate directly with your supervisor. Ask directly for what you consider good pay and tell your expectations to your employer (e.g., I would like to be paid a reasonable wage for internship hours). The more you convey your expectations of good pay, the more likely it is that you will get better pay for your internship.

- How likely are you to negotiate your pay with your prospective supervisor in your meeting? (1 = very unlikely; 5 = very likely)

- Do you think negotiating for pay would negatively affect your relationship with your supervisor? (1 = very unlikely; 5 = very likely)

- Imagine you will be negotiating your pay during this meeting.

- You’ve decided to negotiate for a good hourly wage because negotiation is crucial to get what we want. Negotiating affects the pay we receive and the positions we get into, ultimately influencing how successful we will be in our lives. It is essential that you negotiate for your pay today.

- How anxious would you feel using the suggested negotiation strategy of [being curious or being direct]? (1 = not at all, 7 = very)

- How relaxed would you feel using the suggested negotiation strategy of [being curious or being direct]?

- How nervous would you feel using the suggested negotiation strategy of [being curious or being direct]?

- How comfortable would you feel using the suggested negotiation strategy of [being curious or being direct]?

- How embarrassed would you feel using the suggested negotiation strategy of [being curious or being direct]?

- 1.

- Be Direct

- 2.

- Be Curious

- 3.

- I do not recall

| 1 | The specific items for the measure of social curiosity in the workplace, Openness to People’s Ideas, are, (1) It is important to listen to ideas from people who think differently, (2) I value colleagues with different ideas, (3) I like to hear ideas from colleagues even if they are different from my current line of thinking, and (4) Even when I am confident in my approach to a problem, I like to hear other people’s opinions. |

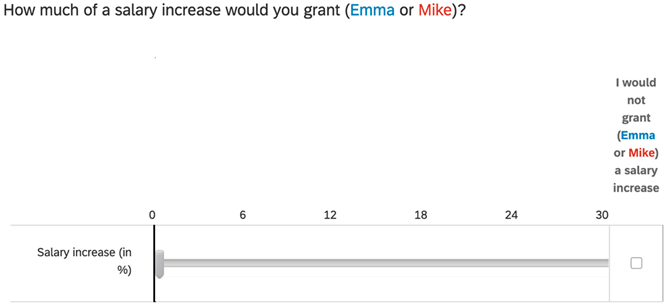

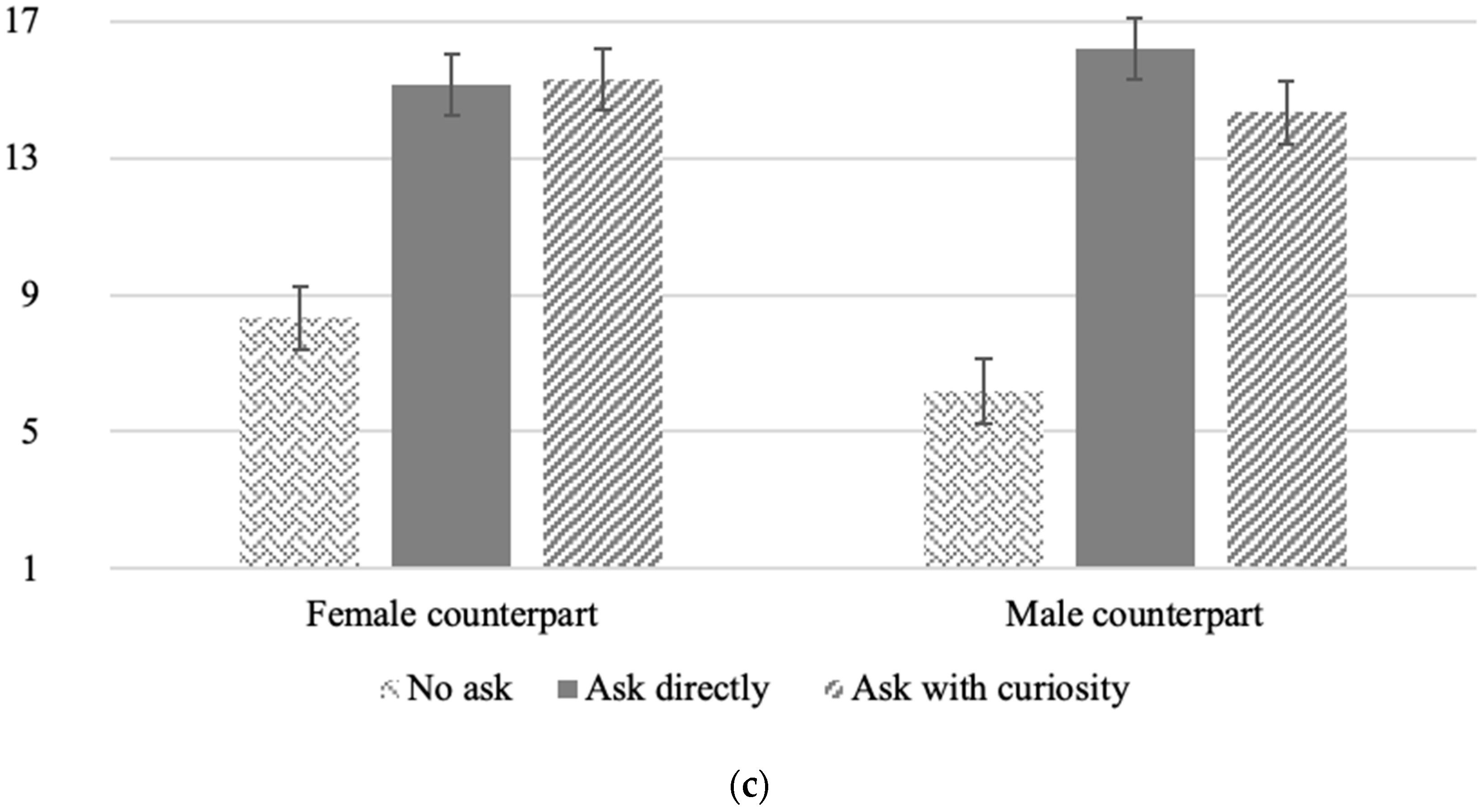

| 2 | Within the curiosity condition, we conducted t-tests comparing men and women’s social and negotiation outcomes. We find that asking with curiosity did not affect women differently than men in terms of willingness to work (p = 0.596), relationship perceptions (p = 0.907) or negotiation outcome (p = 0.543). Additionally, we conducted three separate two-way ANOVAs entering gender and negotiation approach as the independent variables, and willingness to work, relationship perceptions, and negotiation outcome as the dependent variables, respectively. The interactive effects of gender and negotiation approach on willingness to work (p = 0.401), relationship perceptions (p = 0.725), or negotiation outcome (p = 0.839) were not significant (see Figure 1a–c). |

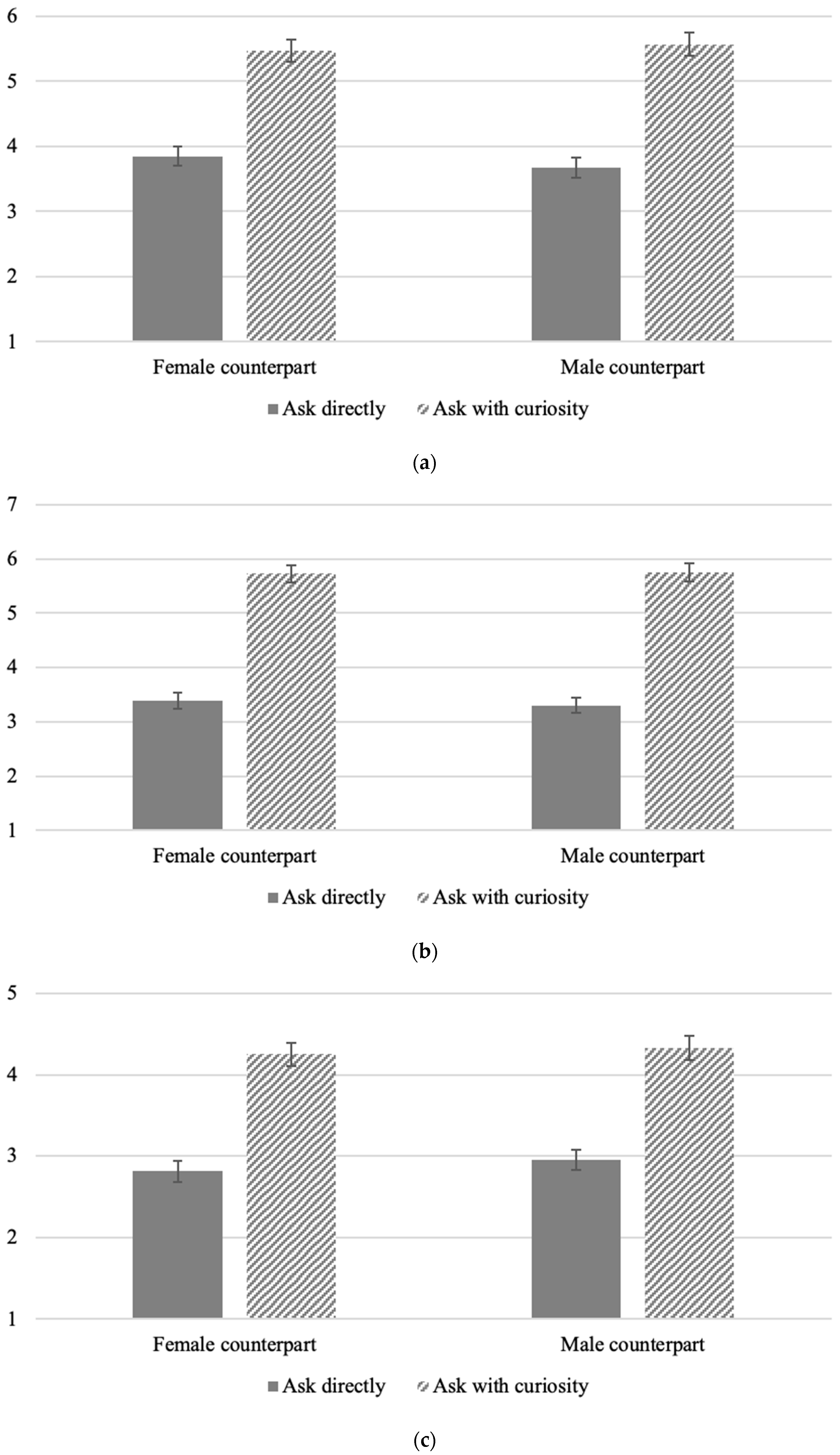

| 3 | Within the curiosity condition, we conducted t-tests comparing men and women’s social and negotiation outcomes. We find that asking with curiosity did not affect women differently than men in terms of willingness to work (p = 0.738), relationship perceptions (p = 0.515) or negotiation outcome in terms of percentage salary increase (p = 0.900). Additionally, we conducted three separate two-way ANOVAs entering gender and negotiation approach as the independent variables, and willingness to work, relationship perceptions, and negotiation outcome as the dependent variables, respectively. The interactive effects of gender and negotiation approach on willingness to work (p = 0.543), relationship perceptions (p = 0.366), or negotiation outcome in terms of percentage salary increase (p = 0.472) were not significant (see Figure 2a–c). |

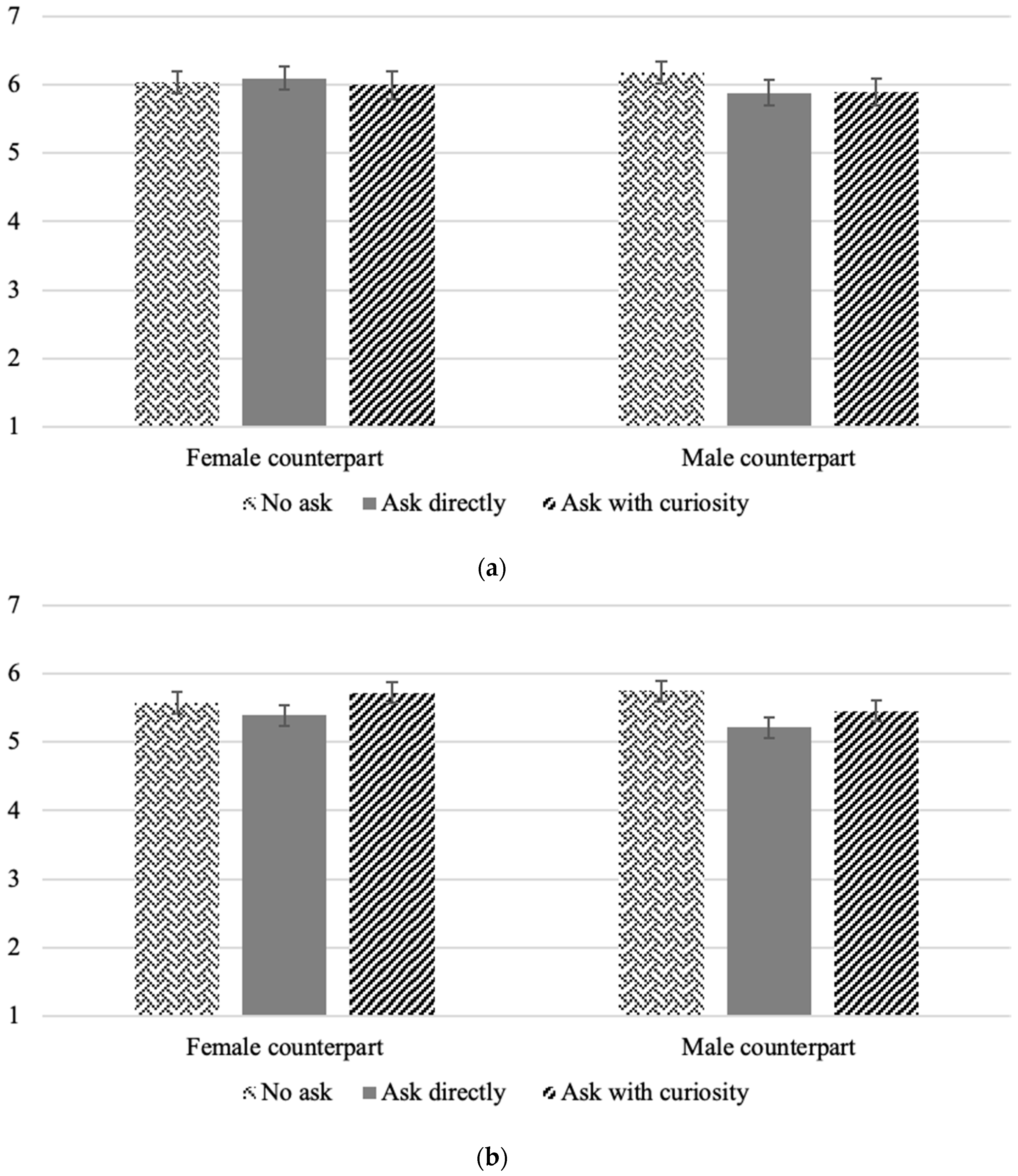

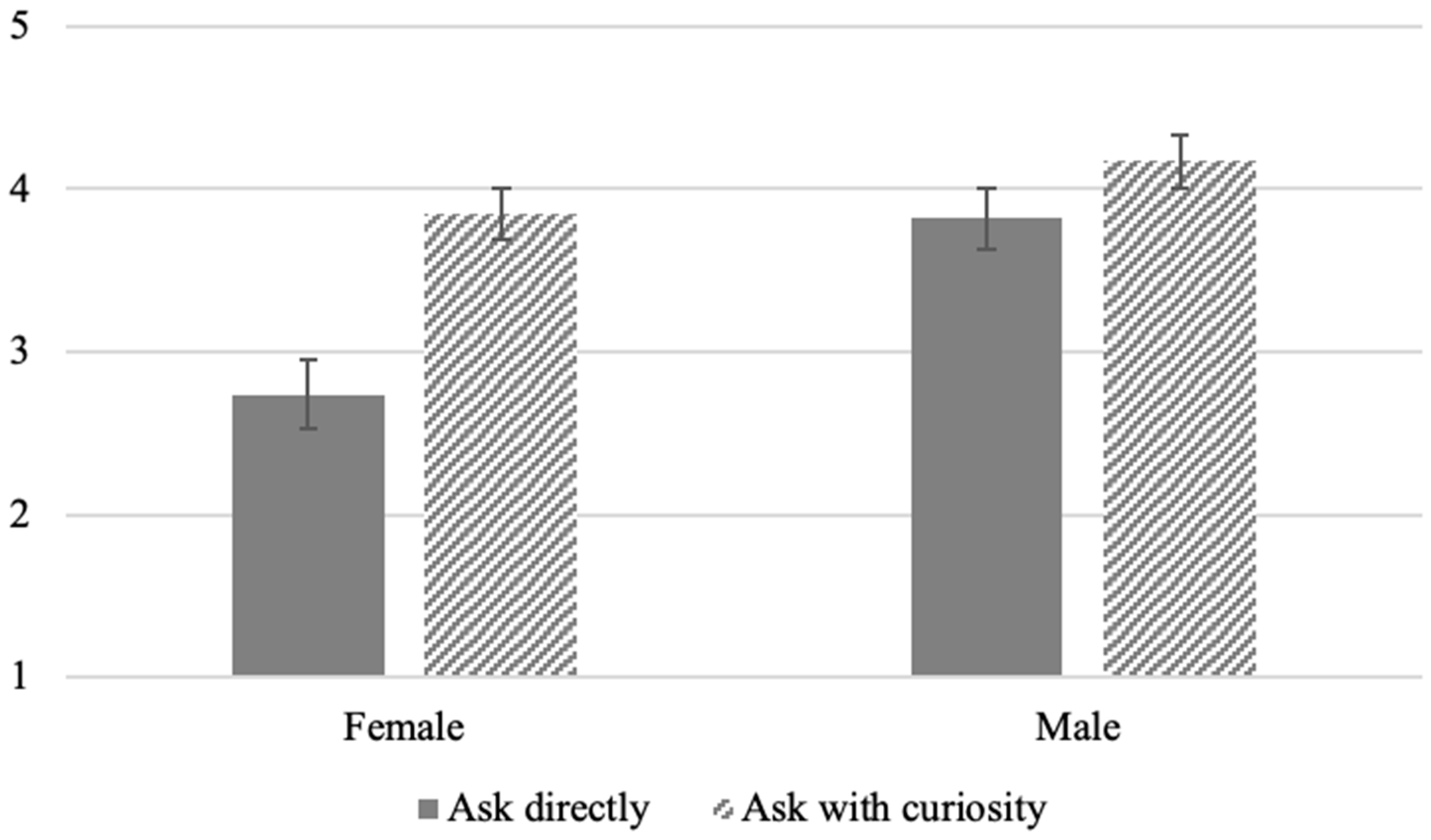

| 4 | We also measured participants’ concern that negotiating would negatively impact the relationship based on Bowles and Babcock (2013). Neither negotiation approach (p = 0.973) nor gender (p = 0.818) predicted participants’ concern that negotiating would have a negative impact on the relationship. Finally, we measured how likely participants were to negotiate their pay with their prospective supervisor (1 = very unlikely; 5 = very likely). There was no significant effect of negotiation approach on negotiation initiation (p = 0.872). Gender had a marginally significant effect such that woman were less likely to initiate a negotiation compared to men, F(1, 156) = 3.69, p = 0.056, ηp2 = 0.02. There was no significant interaction effect of gender and negotiation approach on negotiation initiation. |

| 5 | In our sample, 77 participants identified as woman (49%), 78 as man (49%), 1 as transgender woman, 1 as transgender man, and 1 as non-binary. We created a gender variable, coding participants who identified as woman and transgender woman as 1, and those who identified as man and transgender man as 0. We excluded from analysis the participant who identified as non-binary. |

References

- Ainley, Mary D. 1998. Interest in learning and the disposition of curiosity in secondary students: Investigating process and context. In Interest and Learning: Proceedings of the Seeon Conference on Interest and Gender. Kiel: IPN, pp. 257–66. [Google Scholar]

- Amanatullah, Emily T., and Catherine H. Tinsley. 2013. Ask and ye shall receive? How gender and status moderate negotiation success. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 6: 253–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanatullah, Emily T., and Michael W. Morris. 2010. Negotiating gender roles: Gender differences in assertive negotiating are mediated by women’s fear of backlash and attenuated when negotiating on behalf of others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98: 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, Carolina. 2023. Gender Pay Gap in US Hasn’t Changed Much in Two Decades. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, March 1, Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2023/03/01/gender-pay-gap-facts/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Artz, Benjamin, Amanda H. Goodall, and Andrew J. Oswald. 2018. Do women ask? Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 57: 611–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babcock, Linda, Michele Gelfand, Deborah Small, and Heidi Stayn. 2006. Gender Differences in the Propensity to Initiate Negotiations. In Social Psychology and Economics. Edited by David De Cremer, Marcel Zeelenberg and J. Keith Murnighan. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 239–59. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117: 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, Julia. 2011. “Passing the buck”: Incongruence between gender role and topic leads to avoidance of negotiation. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 4: 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, Julia B., and Linda Babcock. 2012. Negotiation topic as a moderator of gender differences in negotiation. Psychological Science 23: 743–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasi, Barbara, and Heather Sarsons. 2022. Flexible wages, bargaining, and the gender gap. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 137: 215–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothby, Erica J., Gus Cooney, and Maurice E. Schweitzer. 2023. Embracing Complexity: A Review of Negotiation Research. Annual Review of Psychology 74: 299–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Hannah Riley, and Linda Babcock. 2013. How can women escape the compensation negotiation dilemma? Relational accounts are one answer. Psychology of Women Quarterly 37: 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Hannah Riley, Bobbi Thomason, and Julia B. Bear. 2019. Reconceptualizing what and how women negotiate for career advancement. Academy of Management Journal 62: 1645–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Hannah Riley, Linda Babcock, and Kathleen L. McGinn. 2005. Constraints and triggers: Situational mechanics of gender in negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89: 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Hannah Riley, Linda Babcock, and Lei Lai. 2007. Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: Sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 103: 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, David, Ana Rute Cardoso, and Patrick Kline. 2016. Bargaining, sorting, and the gender wage gap: Quantifying the impact of firms on the relative pay of women. Quarterly Journal of Economics 131: 633–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 2013. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Cambridge: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, John W., and William D. Crano. 1988. Inferred evaluation and the relation between attitude similarity and interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Dannals, Jennifer E., Julian J. Zlatev, Nir Halevy, and Margaret A. Neale. 2021. The dynamics of gender and alternatives in negotiation. Journal of Applied Psychology 106: 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickler, Jessica. 2019. Free Salary Negotiation Classes for Women Aim to Narrow the Pay Gap. CNBC. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/07/free-salary-negotiation-classes-for-women-aim-to-narrow-the-pay-gap.html (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Eagly, Alice H. 1987. Reporting sex differences. American Psychologist 42: 756–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Wendy Wood. 2012. Social role theory. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology 2: 458–76. [Google Scholar]

- England, Paula, Andrew Levine, and Emma Mishel. 2020. Progress toward gender equality in the United States has slowed or stalled. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117: 6990–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feintzeig, Rachel, and Rachel Emma Silverman. 2015. Haggle over salary? It’s not allowed. The Wall Street Journal. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/some-companies-bar-job-applicants-from-haggling-over-pay-1432683568 (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Fisher, Roger, William L. Ury, and Bruce Patton. 2011. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement without Giving In. New York: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, Susan T., Amy J. C. Cuddy, and Peter Glick. 2007. Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11: 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, Susan T., Amy J. C. Cuddy, Peter Glick, and Jun Xu. 2002. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L. 1998. What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology 2: 300–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Spencer H., and Karyn Dossinger. 2017. Pliable guidance: A multilevel model of curiosity, feedback seeking, and feedback giving in creative work. Academy of Management Journal 60: 2051–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. In Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press, vol. 1, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Arenaz, Iñigo, and Nagore Iriberri. 2019. A review of gender differences in negotiation. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, Chelsea D. 2019. Exploring the Role of Gender and Race in Salary Negotiations. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Karen, Michael Yeomans, Alison Wood Brooks, Julia Minson, and Francesca Gino. 2017. It doesn’t hurt to ask: Question-asking increases liking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113: 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izard, Carroll E. 1977. Differential emotions theory. In Human Emotions. Boston: Springer, pp. 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, Todd B. 2002. Social anxiety dimensions, neuroticism, and the contours of positive psychological functioning. Cognitive Therapy and Research 26: 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, Todd B. 2004. Curiosity. In Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification. Edited by Christopher Peterson and Martin E. P. Seligman. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association and Oxford University Press, pp. 125–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, Todd B., and John E. Roberts. 2004. Trait and state curiosity in the genesis of intimacy: Differentiation from related constructs. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 23: 792–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, Todd B., David J. Disabato, Fallon R. Goodman, and Patrick E. McKnight. 2020a. The Five-Dimensional Curiosity Scale Revised (5DCR): Briefer subscales while separating overt and covert social curiosity. Personality and Individual Differences 157: 109836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, Todd B., David J. Disabato, Fallon R. Goodman, Carl Naughton, and Patrick E. McKnight. 2018. The five-dimensional curiosity scale: Capturing the bandwidth of curiosity and identifying four unique subgroups of curious people. Journal of Research in Personality 73: 130–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, Todd B., Fallon R. Goodman, David J. Disabato, Patrick E. McKnight, Kerry Kelso, and Carl Naughton. 2020b. Curiosity has comprehensive benefits in the workplace: Developing and validating a multidimensional workplace curiosity scale in United States and German employees. Personality and Individual Differences 155: 109717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kray, Laura, Jessica Kennedy, and Margaret Lee. 2023. Now, Women Do Ask: A Call to Update Beliefs about the Gender Pay Gap. Academy of Management Discoveries, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, Katharina G., Julia AM Reif, Tamara Kaschner, and Felix C. Brodbeck. 2018. Gender differences in the initiation of negotiations: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 144: 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, Angelica, and Sreedhari D. Desai. 2023. What’s Race Got to Do with It? The Interactive Effect of Race and Gender on Negotiation Offers and Outcomes. Organization Science 34: 935–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, Robert W., Ashleigh Shelby Rosette, and Ella F. Washington. 2012. Can an agentic Black woman get ahead? The impact of race and interpersonal dominance on perceptions of female leaders. Psychological Science 23: 354–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazei, Jens, J. Hüffmeier, Philipp Alexander Freund, Alice F. Stuhlmacher, Lena Bilke, and Guido Hertel. 2015. A meta-analysis on gender differences in negotiation outcomes and their moderators. Psychological Bulletin 141: 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, Sonya, and Laura J. Kray. 2022. The mitigating effect of desiring status on social backlash against ambitious women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 102: 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mislin, Alexandra A., Ece Tuncel, and Robin L. Pinkley. 2023. I’m Curious…Do Negotiators Have to Give Up Value When the Relationship Matters? Academy of Management Proceedings 2023: 13070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Women’s Law Center. 2022. Salary Range Transparency Reduces Gender Wage Gaps. October 28. Available online: https://nwlc.org/resource/salary-range-transparency-reduces-gender-wage-gaps/# (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Paquette, Danielle. 2015. Boston Is Offering Free Negotiation Classes to Every Woman Who Works in the City. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/11/13/boston-wants-to-teach-every-woman-in-the-city-to-negotiate-better-pay/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Peters, Ruth A. 1978. Effects of anxiety, curiosity, and perceived instructor threat on student verbal behavior in the college classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology 70: 388–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkley, Robin L., Terri L. Griffith, and Gregory B. Northcraft. 1995. “Fixed pie” a la mode: Information availability, information processing, and the negotiation of suboptimal agreements. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 62: 101–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, Theodore A., and David C. Zuroff. 1988. Interpersonal consequences of overt self-criticism: A comparison of neutral and self-enhancing presentations of self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 1054–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, Julia A. M., Fiona A. Kunz, Katharina G. Kugler, and Felix C. Brodbeck. 2019. Negotiation contexts: How and why they shape women’s and men’s decision to negotiate. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research 12: 322–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, Thomas G., and Jamie L. Callahan. 2004. Affect, curiosity, and socialization-related learning: A path analysis of antecedents to job performance. Journal of Business and Psychology 19: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, Britta. 2006. Curiosity about people: The development of a social curiosity measure in adults. Journal of Personality Assessment 87: 305–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, Laurie A. 1998. Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74: 629–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, Laurie A., and Peter Glick. 1999. Feminized management and backlash toward agentic women: The hidden costs to women of a kinder, gentler image of middle managers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, Laurie A., and Peter Glick. 2001. Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues 57: 743–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säve-Söderbergh, Jenny. 2019. Gender gaps in salary negotiations: Salary requests and starting salaries in the field. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 161: 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, Tony L., and Thomas M. Tripp. 1998. Coffee Contract. Evanston: Dispute Resolution Research Center, Northwestern University. [Google Scholar]

- Small, Deborah A., Michele Gelfand, Linda Babcock, and Hilary Gettman. 2007. Who goes to the bargaining table? The influence of gender and framing on the initiation of negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 93: 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toosi, Negin R., Shira Mor, Zhaleh Semnani-Azad, Katherine W. Phillips, and Emily T. Amanatullah. 2019. Who can lean in? The intersecting role of race and gender in negotiations. Psychology of Women Quarterly 43: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stumm, Sophie, and Phillip L. Ackerman. 2013. Investment and intellect: A review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 139: 841–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Stumm, Sophie, Benedikt Hell, and Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic. 2011. The hungry mind intellectual curiosity is the third pillar of academic performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science 6: 574–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciszke, Bogdan. 1994. Multiple meanings of behavior: Construing actions in terms of competence or morality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeomans, Michael, Alison Wood Brooks, Karen Huang, Julia Minson, and Francesca Gino. 2019. It helps to ask: The cumulative benefits of asking follow-up questions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 117: 1139–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeomans, Michael, Julia Minson, Hanne Collins, Frances Chen, and Francesca Gino. 2020. Conversational receptiveness: Improving engagement with opposing views. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 160: 131–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mislin, A.; Tuncel, E.; Prewitt, L. When Women Ask, Does Curiosity Help? Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13030152

Mislin A, Tuncel E, Prewitt L. When Women Ask, Does Curiosity Help? Social Sciences. 2024; 13(3):152. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13030152

Chicago/Turabian StyleMislin, Alexandra, Ece Tuncel, and Lucie Prewitt. 2024. "When Women Ask, Does Curiosity Help?" Social Sciences 13, no. 3: 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13030152

APA StyleMislin, A., Tuncel, E., & Prewitt, L. (2024). When Women Ask, Does Curiosity Help? Social Sciences, 13(3), 152. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13030152