Abstract

The literature on inclusive research has established its relationship with self-advocacy for people with intellectual disabilities. Self-advocacy has been described as both a requirement and a result of inclusive research. Additionally, the process of becoming an inclusive researcher can be seen as self-advocacy for people with intellectual disabilities. As inclusive research continues to become more prominent, and more people with intellectual disabilities become inclusive researchers, we need to continue to consider this fundamental relationship and how self-advocacy and inclusive research can inform and support each other. In this paper, we first discuss the history of self-advocacy and inclusive research and what inclusive researchers have shared about the relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research. We then present the experiences of an inclusive researcher with intellectual disability with self-advocacy and how the process of becoming an inclusive researcher impacted those experiences. We conclude the paper with reflections on how future inclusive research should consider the role of self-advocacy.

Plain language summary:

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

1. Introduction

1.1. About This Article

This article is about the relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research. We discuss the history of self-advocacy by people with intellectual disabilities and inclusive research. Inclusive research aims to more effectively include people with intellectual disabilities in research, for example as research team members. We explore what inclusive researchers have written about the relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research and present the experiences of an inclusive researcher with intellectual disability with self-advocacy.

1.2. About Us

Three authors wrote this article together. The first author [Courtney] identifies as a person with intellectual disability. She has been a self-advocate for 20 years, and a co-researcher for 5 years. The second author [Lieke] is a university researcher with over 10 years of experience conducting research with people with intellectual disabilities. Courtney and Lieke have been doing inclusive research together for five years and have completed three research projects together. The third author [Claire] is a graduate student who has been working with the second author.

1.3. How We Wrote This Article

Lieke and Courtney discussed writing an article together for this special issue. Lieke proposed several topics to write about for this article. Courtney selected the topic of self-advocacy and inclusive research. We wanted to write about this topic as we believe it is important for people with intellectual disabilities to be strong self-advocates and that being a self-advocate is important for being an inclusive researcher. While others have touched on the link between self-advocacy and inclusive research (Atkinson 2002; Henderson and Bigby 2016; Hopkins et al. 2022; Walmsley and Johnson 2003; Walmsley 2014; Walmsley et al. 2018, 2022), these publications tend to do so only briefly and they do not provide much space for the perspective of a researcher with an intellectual disability. To contextualize the experiences of Courtney, we provide a discussion of the history of both self-advocacy and inclusive research. These histories are strongly connected, but they are rarely discussed together in detail. This is important, as critical reflection and analysis of the relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research can help to inform the future development of inclusive research.

Courtney wrote down the first ideas of what we could discuss in the article, and Lieke added to these ideas and drafted the abstract for the article. Lieke wrote down a list of questions about Courtney’s experiences with self-advocacy and inclusive research for Courtney to answer. Courtney wrote down answers to the questions. Lieke then helped to organize the answers into writing for the article and asked Courtney follow up questions about her experiences. Lieke and Courtney went back and forth several times until we had all the information we needed to include in the article. Lieke and Courtney decided to ask Claire to help to write the article. Claire helped to find literature about self-advocacy and inclusive research and helped to write the sections of the article in which we discuss this literature. Lieke and Courtney helped to finalize these sections. Together, we came up with ideas for the conclusion of the article and Lieke wrote that section. We decided to include plain language summaries with each section of the article. Lieke drafted them, and Courtney and Claire reviewed them. Lieke coordinated the timeline of finishing the article and submitting it.

The perspectives of researchers with intellectual disabilities are often absent from articles or only selectively presented (Strnadová and Walmsley 2018). We need to pay attention to power relationships in inclusive research teams and make sure that the voices of researchers with intellectual disabilities are heard in academia (Strnadová and Walmsley 2018; Tilley et al. 2020). In an earlier article we wrote together (van Heumen et al. 2024), Lieke and Courtney decided together that Lieke would lead the writing of the article and be the first author, as Lieke had more experience with writing, and this was the first writing project for Courtney and hence her first opportunity to learn about the writing stage of the research process. For the current article, we deemed it appropriate for Courtney to be listed as the first author as she took the lead on deciding the topic of the article and her writing about her experiences as a self-advocate and researcher added most significantly to the content of the article.

A large number of different terms are being used in the field to refer to individuals with and without disabilities who are involved in inclusive research, such as ‘academic researcher’, ‘university researcher’, ‘inclusive researcher, ‘co-researcher’, etc. Sometimes these terms are used interchangeably (Ghaderi et al. 2023). In this article, we use the term ‘inclusive researchers’ to refer to all individuals involved in inclusive research. When needed, we make a distinction between researchers who identify as having an intellectual disability and those who do not.

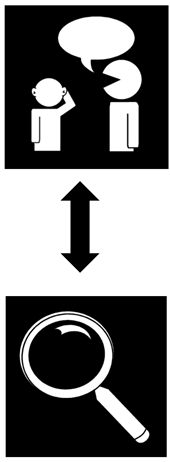

1.4. Plain Language Summary

|  |

|  Courtney  Lieke  Claire |

|  |

2. The History of Self-Advocacy

2.1. A Background on Self-Advocacy

Self-advocacy is often defined as an act of speaking up about and defending one’s needs and rights, while also being able to make choices based on those needs and rights. People First London’s definition of self-advocacy is frequently cited in the literature. Their definition consists of the following elements (cited in Atkinson 2002):

- Speaking up for yourself;

- Standing up for your rights;

- Making choices;

- Being independent;

- Taking responsibility for yourself.

The U.S.-based Self-Advocacy Resource and Technical Assistance Center adds an element of community to the definition of self-advocacy (SARTAC 2023). This definition is in line with Bersani’s argument that self-advocacy is a social movement that seeks out ideological change in the ways people with intellectual disabilities are thought of and treated (cited in Walmsley and Johnson 2003). Collective organizing happens through self-advocacy organizations such as ‘People First London’ in the UK, ‘Self Advocates Becoming Empowered’ (SABE) in the USA, and ‘Reinforce’ in Australia. According to SARTAC (2023), all people with intellectual disabilities can participate in self-advocacy, and doing so helps them to accomplish their goals. A key aspect of self-advocacy is that people with intellectual disabilities speak up for what they and those identifying with them need, and that allies support them but do not speak on their behalf (Nelis 2018). Self-advocacy is important to many people with intellectual disabilities (Henderson and Bigby 2016), and membership of self-advocacy groups has a positive impact on their lives. For example, Frawley and Bigby (2015) reported that members of a self-advocacy group in Australia gained a sense of belonging, social connections, and meaningful work opportunities through their involvement in self-advocacy. Others have reported that self-advocacy groups help to develop leadership skills and promote the claiming of a disability identity among people with intellectual disabilities (Atkinson 2002; Caldwell 2010; Tilley et al. 2020).

2.2. The History of Self-Advocacy

Though historical records tend to demonstrate that self-advocacy movements emerged in Western countries during the second half of the twentieth century, there is evidence that people with intellectual disabilities started advocating for their own needs and wellbeing much earlier in history. For example, people with intellectual disabilities frequently tried to escape (abscond) long-stay hospitals as an act of resistance in the UK during the first half of the twentieth century (O’Driscoll and Walmsley 2010). However, actions such as these have not always been interpreted and credited as self-advocacy (Buchanan and Walmsley 2006; Walmsley 2014). This credit is important, as it shows that people with disabilities have long persisted to change their circumstances (Nielsen 2012).

After World War II, the protection of universal human rights became a global concern. Civil rights movements gained worldwide traction in their struggle against the dehumanization of women, Black people, people of color, and indigenous people. Disability movements emerged alongside these civil rights movements and included groups that specifically promoted the rights of people with intellectual disabilities (Carey 2009; Nielsen 2012).

In the U.S. and countries such as the UK, Sweden, and Denmark, advocacy groups were originally spearheaded by parents and professionals. These groups, such as ‘The Arc’ in the U.S., called for educational opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities as well as deinstitutionalization (Nielsen 2012). Their advocacy was inspired by normalization theory which originated in Sweden in the 1970s. Normalization theory proposes that disabled people should live a life that resembles that of non-disabled people, live among non-disabled people, and be able to make their own choices (Wehmeyer et al. 2000).

Though advocacy of parents and professionals is important to support people with intellectual disabilities, they should not dominate conversations. In response, people with intellectual disabilities started to organize themselves into self-advocacy groups. The UK self-advocacy movements developed “in opposition to parents’ organizations” (Buchanan and Walmsley 2006, p. 134). In contrast, the largest self-advocacy group in Denmark emerged from a parent- and professional-led organization that acknowledged the need for self-advocacy (Bylov 2006). In Australia, self-advocacy group ‘Reinforce’ developed from a camp organized by Middle Park Social Club, a drop-in center for people with intellectual disabilities (Henderson and Bigby 2016). Shoultz reports in 1991 that during the preparation of their first convention by a group of self-advocates in Oregon, in the U.S., in 1975, one member criticized the use of the slur ‘retarded’ and stated: “We are people first” (cited in Hayden and Nelis 2002). The U.S. self-advocacy movement was named ‘People First’ after this statement. The conferences organized by self-advocacy groups in the early stages of the movement were crucial for the development of international connections and the emergence of self-advocacy groups around the world. For example, after attending the International Self-Advocacy Conference of 1984 in the U.S., UK self-advocates started ‘People First London’ (Walmsley et al. 2022).

Self-advocacy groups around the world fight to improve the participation of people with intellectual disabilities within all parts of society. Self-advocacy groups have provided information and resources to empower individuals with intellectual disabilities and to support the development of their self-advocacy skills. The Illinois Self-Advocacy Alliance, for instance, provides documents with guidelines for organizing online meetings and asking questions during committee meetings (Illinois Self-Advocacy Alliance 2011). Self-advocacy groups have also engaged in political activism. For example, SABE, a nation-wide initiative of U.S. self-advocacy groups, launched their first campaign by and for people with intellectual disabilities against their institutionalization in 1994 (Friedman and Beckwith 2014). Similarly, the Australian self-advocacy group ‘Reinforce’ occupied buildings and held protests for policy changes in the 1980s (Henderson and Bigby 2016). Self-advocacy can also show up in smaller ways that do not challenge the power differences between people with and without intellectual disabilities (Aspis 2002). Aspis (2002) argues that self-advocacy can focus on small issues like getting a coffee machine or changing labels on buses. Efforts by people with intellectual disabilities and other disabled people have led to substantial changes to their rights both in the U.S. and worldwide. For example, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) recognizes the importance of advocacy organizations in overseeing the implementation of the UNCRPD and promotes the right to accessible research results (art. 4, art. 29, art. 31, United Nations 2006).

Self-advocacy groups have had to grapple with a tension between building confidence among members and recruiting new members, and their collective action and representation. Additionally, issues of importance to self-advocacy groups have included the role of supporters without intellectual disabilities such as family members and staff, the inclusion of people with high support needs, their level of independence from organizations that provide services to people with intellectual disabilities, and having sufficient funding available (Walmsley et al. 2022).

Though some literature has explored the life histories of self-advocates (e.g., Caldwell 2010; Goodley 2000; Traustadottir 2006) and the history of individual self-advocacy groups (e.g., Walmsley 2014; Frawley and Bigby 2015), a gap remains in the knowledge on the history of self-advocacy moments (Walmsley 2014; Walmsley et al. 2022). Most research on the history of self-advocacy focuses on developments in specific countries (Bylov 2006; Callus et al. 2022; Ferguson 2019; Henderson and Bigby 2016; Hutton et al. 2017; Walmsley 2014; Waltz et al. 2015), which does not necessarily provide insight into international self-advocacy movements. Additionally, a lack of research on the development of self-advocacy in non-Western countries might skew attempts to understand the history of international self-advocacy movements. Finally, more research on self-advocacy should be conducted by people with intellectual disabilities to capture their experiences and perspectives. Walmsley et al. (2022) argue that the general lack of research on self-advocacy might be caused by concerns about whether non-disabled people are allowed to write this history. However, researchers without intellectual disabilities can serve as important allies in supporting self-advocates in recording and accessing their own histories. Applying the principles of inclusive research to this dilemma (which are explored in detail below) holds promise.

2.3. Plain Language Summary

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|   |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

3. The History of Inclusive Research

With the rise of civil rights and disability movements, debates about the dehumanizing effects of traditional approaches to research became more prominent (Walmsley and Johnson 2003). Walmsley and Johnson (2003) situated the emergence of inclusive research within and alongside developments in knowledge production aimed at highlighting the voices of oppressed people in research such as the increased presence of qualitative research, feminist research, and participatory action research. Research that included people with intellectual disabilities significantly increased in the 1990s (Beail and Williams 2014). The shift from research ‘on’ to ‘with’ people with intellectual disabilities has been found to be instrumental in combating their social exclusion and fostering social change (Björnsdóttir and Svensdottir 2008; Johnson 2009).

In 2001, Walmsley proposed ‘inclusive research’ as an umbrella term for any research that actively includes people with intellectual disabilities (Walmsley 2001). In 2003, Walmsley and Johnson established a definition of inclusive research that became the foundation for the further development of this field (Walmsley and Johnson 2003). The 2003 definition was updated in 2018, and includes five criteria. Inclusive research advances social change and fosters the belonging and life quality of people with intellectual disabilities; grounds itself in their concerns and shapes the research process based on their experiences; seeks to acknowledge, promote, and share their contributions; results in information that supports them in their (self-)advocacy; and consists of researchers that support their cause (Strnadová and Walmsley 2018). These criteria have provided an important framework as inclusive researchers have explored the importance, possibilities, challenges, and limits of inclusive research.

Nind (2016) made important contributions to conceptualizing inclusive research as well. According to Nind, the first generation of inclusive research established the need for people with intellectual disabilities to conduct research and showed how research can be conducted inclusively. Nind (2016) argued that the second generation of inclusive research should focus more on evaluating the quality of inclusive research and produce knowledge about more than the research process itself. However, Walmsley et al. (2018) argued that the field should not move to a second generation too quickly. They stated that such a move to focus on outcomes might ignore the necessity of further research into what inclusive research should look like. They argued that a focus on the process of inclusive research is still valuable, especially as it illustrates the possibilities for acknowledging and sharing contributions made by people with intellectual disabilities (Walmsley et al. 2018). Inclusive researchers continue to raise questions about the process of inclusive research and call for critical discussions on how inclusion is practiced throughout the various stages of inclusive research to establish a clear framework of best practices. These discussions are complicated by the fact that most articles do not include reasons for why people with intellectual disabilities are excluded in certain stages of the research and lack reflection on how inclusion actually took place within the research (Ghaderi et al. 2023). Inclusive research teams should prioritize documenting how they work together (as we have included in the introduction), and discuss what challenges they encounter, so the field can develop this suggested framework of best practices.

Not all inclusive research projects have included people with intellectual disabilities at each stage of the research process. Bigby et al. (2014b) observed three main approaches used in the field. In the first approach, people with intellectual disabilities are consulted on the design, topic, or process of research without being involved in conducting the research. In the second approach, people with intellectual disabilities take the lead and are in full control of the research process. The third approach is collaborative in nature, and this approach values the different contributions and skills of researchers with and without intellectual disabilities equally. In this approach, tasks and responsibilities are distributed as evenly as possible to move away from hierarchies, and the shared interests and concerns of researchers with and without intellectual disabilities are emphasized. This collaboration creates new knowledge that neither group could provide alone (Bigby et al. 2014b). Inclusive researchers may utilize more than one approach at the same time or switch their approach over time. For example, García Iriarte et al. (2023) discussed how the approach of their inclusive research team moved from non-disabled researchers making all decisions to researchers with intellectual disabilities making decisions on the team’s research topics, methods, and reports. As we discuss as well, the way our inclusive research team worked together also changed over time as both the researcher with and the researcher without intellectual disabilities gained more experience with inclusive research.

Inclusive researchers have observed a lack of research where people with intellectual disabilities are involved in all steps of the research process or where they are fully in control of the research (Ghaderi et al. 2023). However, some researchers have expressed that research collaborations can be rewarding and meaningful for inclusive researchers with and without intellectual disabilities even when research projects are not fully inclusive at all stages of the research process (Björnsdóttir and Svensdottir 2008).

The extent to which people with intellectual disabilities are included in research projects depends on the opportunities and constraints of the context in which the research is conducted, and the attitudes, experience levels, and resources of everyone involved in the project. It has been argued that any kind of research can be made inclusive to at least some extent (Björnsdóttir and Svensdottir 2008). An important complication discussed by Ghaderi et al. (2023) is that non-disabled researchers experience difficulties recruiting people with intellectual disabilities for their research teams. Non-disabled researchers usually already know their team members with intellectual disabilities or they recruit them through (self-)advocacy groups. In some instances, local authorities, disability rights groups, or service organizations play a role in recruitment. A lack of self-advocacy has been identified as an obstacle for recruiting researchers with intellectual disabilities, as is the case in Africa (Kahonde 2023).

Systemic barriers to the inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities in research have been explored by inclusive researchers as well. The issue of people with intellectual disabilities providing informed consent has caused debates among researchers and ethics review boards who can take on a protective role (McDonald and Kidney 2012). Fears that people with intellectual disabilities are unable to understand research or might become the subject of abuse has at times led to them being excluded from research (McDonald and Kidney 2012; Santinele Martino and Fudge Schormans 2018). The exclusion of people labeled with severe and profound intellectual disabilities is especially at risk (McDonald and Kidney 2012). There is clear agreement in the field that they are underrepresented in inclusive research (Ghaderi et al. 2023; Milner and Frawley 2019; de Haas et al. 2022). de Haas et al. (2022) argue that inclusive researchers should develop a deep understanding of people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities and embrace new possibilities for inclusive research rather than modifying currently accepted models of conducting inclusive research. Additionally, inclusive researchers should communicate effectively about the principles of inclusive research and advocate for the inclusion of people with intellectual disabilities in research to combat discriminatory attitudes and other barriers.

The field has acknowledged that inclusive research requires adequate training and support for researchers both with and without intellectual disabilities to develop skills and confidence (Bigby and Frawley 2010; Flood et al. 2013; Di Lorito et al. 2018; Mikulak et al. 2022). Inclusive research teams have developed various approaches to training to support the inclusive research process (Nind et al. 2016). O’Brien et al. (2022) argue that training in inclusive research practices should be more widely available and recommend training to be developed jointly by inclusive researchers with and without disabilities. Scholars in Africa have recently pointed out the need to take into account local contexts when developing training and to make sure that training is accessible and meets the needs of people with intellectual disabilities in specific regions (Kahonde 2023).

Finally, though inclusive research was started in the academy by non-disabled researchers, inclusive research is now conducted in non-academic settings as well with or without relationships with non-disabled researchers. This research has strong parallels with the work of advocacy groups (Crombie Angus and Angus 2022; Hopkins et al. 2022). The field of inclusive research should spend more time considering how to support such community-initiated and community-led inclusive research.

Plain Language Summary

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

4. The Relationship between Self-Advocacy and Inclusive Research

The histories of self-advocacy and inclusive research are intertwined. Both developed alongside each other during a time in history when the oppression of people in the margins of societies was criticized and the pursuit of social justice and equality became a central concern. Self-advocacy and inclusive research share the common goal of celebrating the voices and choices of people with intellectual disabilities (de Haas et al. 2022). The acknowledgement that research participation is a part of community participation provided an impetus for the development of new research methodologies and created opportunities for people with intellectual disabilities to hold valued social roles in research (Walmsley and Johnson 2003). Self-advocacy has enabled people with intellectual disabilities to speak up about their lives and experiences and has resulted in some self-advocates participating in research.

Self-advocacy and inclusive research are closely related (Hopkins et al. 2022). Both self-advocacy and inclusive research can empower people with intellectual disabilities (Atkinson 2002). The relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research can be characterized as one where both are influenced by each other (Atkinson 2002). Self-advocacy does not necessarily lead to involvement in research among people with intellectual disabilities, nor does involvement in research lead to engaging in self-advocacy (Atkinson 2002). However, self-advocacy has played a crucial role in making inclusive research possible (Atkinson 2002; Bigby et al. 2014b; Bigby and Frawley 2010; Walmsley and Johnson 2003). Involvement in research relies on and can strengthen the self-advocacy skills of people with intellectual disabilities and, in turn, inclusive research can lead to better self-advocacy (Ghaderi et al. 2023; Johnson 2009). The Irish Clare Inclusive Research Group, a group consisting of self-advocates, said they ‘dig deeper’ in inclusive research compared to advocacy, but that they use their advocacy skills to speak up about issues they want to raise, and use their advocacy skills to promote the findings of their research and to campaign for change (Hopkins et al. 2022).

The deep connections of inclusive research with the self-advocacy movement have been impactful in the representation of issues that matter to people with intellectual disabilities. At the same time, it has been argued that too strong of an emphasis on the capacity and abilities of self-advocates in inclusive research may exclude people with severe and profound disabilities on the grounds of cognitive incompetence (Davy 2019). Inclusive researchers should continue to critically examine who has been included in research and who has not and push the field to new levels and forms of inclusion.

Self-advocacy groups equip people with intellectual disabilities to develop as researchers (Nind 2016). Additionally, people with intellectual disabilities are often recruited for inclusive research through self-advocacy groups (Johnson 2009). Nind’s (2016) observation that the sustainability of self-advocacy groups is threatened due to a lack of funding therefore creates a concern for the future of inclusive research. Many inclusive researchers without disabilities already experience difficulty recruiting people with intellectual disabilities for their research teams (Ghaderi et al. 2023). We need to consider how systems and infrastructures hinder or foster self-advocacy and facilitate connections between researchers and self-advocates. Structures within universities, such as ethics review committees, have negated the autonomy of people with intellectual disabilities, making it hard for them to be included in research (McDonald and Kidney 2012; Santinele Martino and Fudge Schormans 2018). In the U.S., several government-funded programs aim to democratize research and policy by engaging with self-advocates. For example, the University Centers for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities Education, Research, and Service (UCEDDs) recruit self-advocates to serve on advisory committees (Association of University Centers on Disabilities n.d.b), 60% of the members of State Developmental Disability (DD) councils are people with intellectual disabilities and their family members (Administration for Community Living 2023), and Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disabilities (LEND) programs include self-advocates as trainees (Association of University Centers on Disabilities n.d.a).

Additionally, the link between self-advocacy and inclusive research needs to be made in the development of research training for people with intellectual disabilities. Most training models for people with intellectual disabilities focus on explaining what research is, discussing various research methods, and supporting people with intellectual disabilities to gain skills and confidence to engage in and conduct research; but they do not explicitly mention self-advocacy skills (Tuffrey-Wijne et al. 2020; van Heumen et al. 2024). However, it is important for inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities to use their self-advocacy skills to shape their experiences in research, manage power differentials on inclusive research teams, and make an impact through their research.

Despite the important connections between the goals of self-advocacy and inclusive research and the similarities between the skills of self-advocates and inclusive researchers, there is not much inclusive research that explicitly addresses the relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research, and at times the lines between the two are blurred. For example, inclusive research can lead into collective action where the line between research and self-advocacy is not always apparent (Johnson 2009). There is also no agreement on terminology. Where some inclusive researchers explicitly use the term ‘self-advocates’ to refer to people with intellectual disabilities engaging in research (e.g., García Iriarte et al. 2023; Garratt et al. 2022), other inclusive researchers discuss what people with intellectual disabilities can add to inclusive research without being explicit about self-advocacy. In both cases, it is not clear if there is a difference between ‘people with intellectual disabilities’ or ‘co-researchers’ and ‘self-advocates’ participating in inclusive research. Research does not always discuss the skills of co-researchers as self-advocacy skills either (Ghaderi et al. 2023). We argue that it is important to pay attention to the relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research as we turn our gaze towards the future development of inclusive research and consider how best to cultivate and support the next generation of researchers with intellectual disabilities. In doing so, we need to learn from the experiences of inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities such as Courtney’s below.

Plain Language Summary

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

5. The Experiences of a Self-Advocate with Inclusive Research

In this section of the article, Courtney discusses her experiences as a self-advocate and inclusive researcher in the U.S. and explores what it means to hold both of these roles. In this section, Courtney uses a first-person narrative.

5.1. The Road to Become a Self-Advocate

Being a self-advocate means being included in decision making, finding your own voice, and using your own voice to be able to stand up for your own rights and needs as a person with intellectual disability. It is very important and powerful that we learn about self-advocacy as people with intellectual disabilities. The reason I wanted to write a paper about self-advocacy for people with intellectual disabilities is because I strongly think it is important for us to know how to self-advocate. I feel when we do not know how to advocate for ourselves or speak up for ourselves, people without disabilities will have low expectations of us and can take advantage of us. We need to learn and teach self-advocacy skills so we can have a successful meaningful life in anything that we do.

I have been a self-advocate for 20 years, since I went to college. Either you are born into having self-advocacy skills because you may be the type of person who does not hold anything back and “tells it like it is”, or you learn along the way in life how to develop those skills. For some people with intellectual disabilities, it is not an easy task that will happen overnight or in just one day. It takes time and a lot of work and practice. When I was four years old, I had a clear understanding that I had an intellectual disability, and understood what that meant. I did not know what to do or how to handle myself. Life was hard for me when I was young and when I was in high school. Having a disability, I never understood what people would think and say when I would try to advocate for myself. My parents knew I had a disability and wanted to protect me; they did everything for me and advocated for me every step of the way. My dad said: “This is my last baby girl and I don’t want anything to stand in her way so I’m going to advocate for her every step of the way in her life.” When I had to talk to teachers, coaches, mentors, or parents, my parents did it all. I would always hide behind them because I felt scared and I was shy. I did not want to show my true identity. Once I went to college in 2003, my parents said: “You are going off to college, your parents are not going to be there to help you support your self-advocacy skills. You are going to have to learn to deal with this on your own. Come out of your comfort zone, come out of your shell and try to do it yourself.” I advocated for myself for the first time when I was in college and taught myself how to do it. I was alone and people were not going to be by my side doing the work for me so I had to figure it out on my own. I am so glad I did, and I am proud of myself. I became stronger than I had ever been before and now have the courage to do anything I put my mind to. After I learned how to advocate for myself, I started using my new skills at work, in Special Olympics sports, and with friends and family. I am very blessed knowing how to stand up for myself now and to have a strong voice in speaking up for my rights as a person with intellectual disability. I do not let people speak for me and do the work of advocacy for me. I like to be able to handle or at least try to handle every situation on my own. I find my voice by representing myself and ensuring my rights as a person with an intellectual disability are upheld. If it is something I cannot handle on my own then of course I am going to let people help me and speak with me. I am not ashamed of letting people help me and I am not ashamed to ask for help. We all need help in life, even people without an intellectual disability.

At times I have to be persistent and assertive as a self-advocate to reach my goals. I wanted to prove to people at work that I was a person who was determined to do more in my career and move my way up to a higher position. When I eventually decided to talk to my supervisor about a position as an associate teacher, I had to sit myself down and plan out how I was going to approach them and self-advocate. I wanted people to know I was serious about this position and wanted to take full responsibility for it. My supervisor heard me but for a few years kept turning me down. It was not because I had an intellectual disability, it was because there were a few goals my supervisor wanted me to work towards first, such as being able to lead a toddler classroom. As the years went on and I achieved all my goals, I still never got the position. I was told there was someone else more qualified for the position than me. Eventually, my supervisor said that if the person who was hired would not stay the full school year, I could have the position on a trial basis. My supervisor said that we would see how it would work out and that we would evaluate how I did at the end of the year to see if I could handle the position for a full year going forward. I always kept pursuing the position with my supervisor, I never backed down, and I never gave up on my goals and dreams. I stood up for myself and what I believed was right. I believe my supervisor was absolutely right in their choice and decision because I have grown, reached many goals, and overcome many obstacles in my career as a teacher. It made me a stronger person, and I will do anything to achieve my goals in life. I am not going to back down on what I believe is right until I get the job done. I am a believer and a fighter. All people, no matter if they have an intellectual disability or not, should be treated equally and have the same rights, and everyone’s voice and ideas should be heard. If you say a person who is disabled will never be able to achieve goals such as becoming a store manager or running a marathon, you are not treating every individual equally. If a person with a disability is qualified to be a manager and has trained hard to run a marathon, why not let them try and experience those things. If we fail it is okay, at least we were allowed to try something out of our comfort zone.

I use three steps in self-advocacy, inspired by an article written by Nancy Suzanne James (2014):

- Knowing myself inside and out;

- Knowing my needs;

- Knowing how to get what I need in life.

For the first step, I feel that you need to know what type of person you truly are inside and out, before you can even think about advocating for yourself. You need to know yourself so you can be successful in your journey to become a self-advocate. You need to know if you are shy to assert yourself and need help to self-advocate, if you are outgoing and experienced and can self-advocate with no help at all, or if you need help with something like asking for time off but not with something else like getting help with a task at work. For the second step, it is important to believe in yourself as a unique and valuable person. It is also important to know your rights and to know that you are entitled to equality under the law. Then, you need to decide what you want and to clarify for yourself exactly what you need in your life. For the third step, you should reflect on your values and goals and work on your communication skills. You can start small with asking for what you need and work your way up to advocate for bigger issues that matter to you. Being a self-advocate makes you feel a sense of power and a sense of being in control of your own life and your own actions and words. I make choices based on my own values. I understand what matters most to me and why.

When I advocate for myself, I prepare. I have a plan and believe in myself, and prioritize my needs. First, I figure out what I am going to say. I make a list of things that may go well and things that may not go well. I think about how I can advocate for myself in a healthy way. I go in calm, cool, and collected. This helps to get my point across so that others listen and hear what I have to say. Nerves can get the best of us, so we need to recognize our worth. I feel that some people with disabilities who try to self-advocate will come out and say whatever is on their mind. Before we speak, we should know what we are going to talk about and advocate for. This way, what we say will mean something. It is a good idea to write down our ideas about how we will self-advocate rather than going up to a person without being prepared. If we do not have a strong message, others may not take the time to listen because they may not care about disabled adults or our issues may not be important to them. It can be sometimes very intimidating as a person with intellectual disability to go up to someone and talk to them about what we need or want in life. In my opinion, the world goes 50/50 on people with intellectual disabilities. Half of the world will listen to what we have to say and accommodate our needs and give us what we ask for. The other half of the world does not care to listen to us, or even if they do listen they will shut down our ideas and needs immediately. These people look past someone with intellectual disabilities, which I find cruel and wrong. People with intellectual disabilities are everyday people. Others may be very surprised at what we can say when we speak up for ourselves and what we bring to the table. I recommend to other self-advocates that before we speak up, we ask ourselves if the person we want to talk to is someone who cares about disabled people or if we may be wasting our time and energy with this person and this topic and we could be spending our time doing other things.

I have never advocated as part of a group of self-advocates. I think self-advocacy would be easier with a group, as each person gets to speak up to get the point across. The only time I advocate with another person is with my boyfriend Aaron. We are a couple and a team so we help each other with advocacy. Either we advocate together, I advocate for him, or he advocates for me. The Special Olympics programs I participated in did teach me how to support other people with disabilities to self-advocate. I am glad to support others, like people who do not speak.

5.2. Being a Self-Advocate and Inclusive Researcher

When I was asked by Lieke to be part of an inclusive research project, I did say yes right away to being a researcher, but I was a little skeptical about the project and the inclusive research process. When I first started as a researcher, I knew very little about inclusive research. I was not sure how it would eventually work out. Once I was able to test the waters and get a feel for what inclusive research is and what researchers actually do, I thought it was interesting and amazing. In the first project, we created accessible brochures and videos explaining the results of research using health screenings to Special Olympics athletes with intellectual disabilities. We asked a few athletes to read the brochures and to watch the videos. Then, we came back together as a group and asked them how they liked the brochures and videos and if they were easy for them to understand. The athletes gave us their feedback, and we went ahead to make those changes. For the second project, we recruited athletes to participate in an inclusive research training to learn all about what it means to be a co-researcher, like how to ask a research question, how to conduct research, and how to collect and analyze data.

Since the first day of working on our first project 5 years ago, I have been learning everything I need to know and my skills have grown and developed. I am proud of my work and the progress I have made. Lieke was able to help me, guide me, and give me the tools to be successful in my research career. I now know what research is, how to come up with a research question, how to answer that question by collecting and analyzing the data, and how to come up with a conclusion. I also now know how to conduct focus groups and interviews and how to give out surveys and review the survey results. I have learned how to talk to people with intellectual disabilities to get their input on the research and learn from all their ideas. Finally, I have learned how to write an article like this one about self-advocacy and how to be an author.

I use my self-advocacy skills in my work as a researcher. When I first started with inclusive research, I had to find my own voice and build my confidence and self-esteem to self-advocate in research. I needed to communicate clearly, so that others could help me and understand how to support me to be a researcher. Because of my disability, I need to read information to comprehend it. Telling me information in person is not enough. I explained this to Lieke, and now after each meeting I receive the notes about what we talked about. Also, Lieke will email me my tasks. Another example of me using my self-advocacy skills in research is me sharing my ideas for new research projects by email to Lieke. Whenever I have an idea, I always stand up for myself and explain my research questions. Lieke looks at my ideas and never turns them down. She always says what creative ideas I bring to the table, and at our meetings we talk about my ideas and we expand and elaborate on them and talk about how we can go about implementing them.

As an inclusive researcher, I tell my own story and share my personal stories and experiences with the world. Becoming an inclusive researcher has helped me to develop leadership skills. The role as a researcher made me step out of my comfort zone, as I started working as a researcher on a project that I knew nothing about at first. Ever since I started with inclusive research, I have grown and changed a lot. I have learned about so many research topics. Being an inclusive researcher has also boosted my confidence level in ways I never thought possible. I feel empowered as a person with intellectual disability, I have developed independence, and I have learned self-determination skills I did not have before. I also feel I have created a sense of ownership over learning that has increased my self-confidence. I am now more self-aware of my interests and desires and more motivated to share my ideas.

Becoming an inclusive researcher has changed my role as a self-advocate. I am not afraid to self-advocate, speak up, and tell people what is on my mind. I fight for whatever point I am trying to get across in a way that is healthy and respectful so that people will listen to me and take someone with an intellectual disability seriously. I realize that if I fail, I get right back up and never give up. I am always willing to keep on trying until I succeed and get the job done right. We have rights like anyone else, no matter what we look like or if we have a disability or not.

I have realized that inclusive research allows for people like me to be involved and included to share our personal experiences. I feel I am getting so many other people with intellectual disabilities interested and involved in something they do not know much about, just like I did not know much about research when I first started. I am letting other people with intellectual disabilities know exactly what inclusive research is, and I am supporting them to be more included in the research process. This way, they can tell others about inclusive research and tell their own personal stories and experiences. This is important because they are the people who truly have lived those life experiences.

5.3. Plain Language Summary

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

6. Reflecting on the Experiences of a Self-Advocate with Inclusive Research

Courtney’s experiences illustrate the important relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research. Courtney discussed how she developed self-advocacy skills as a person with intellectual disability. For most of her life, Courtney engaged in self-advocacy as an individual and not as part of a self-advocacy group. The literature often emphasizes self-advocacy groups as a place to train and recruit self-advocates for inclusive research (Johnson 2009; Ghaderi et al. 2023). However, Courtney’s experiences show how important it is to support people with intellectual disabilities in their individual self-advocacy as well, even when they are not a member of a self-advocacy group.

Courtney talked about how her self-advocacy skills helped her as she learned about inclusive research and started to participate in an inclusive research team. Courtney also shared her ideas about what the research should address. Finally, she used her self-advocacy skills to discuss her access needs which helped her to participate in the research. Highlighting what inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities perceive as facilitators and barriers to getting their access needs met is an important issue in the inclusive research literature (Embregts et al. 2018; Schwartz et al. 2019).

Courtney’s engagement in inclusive research has allowed her to connect with other people with intellectual disabilities on issues that matter to them, to tell them about inclusive research, and to share her experiences through the dissemination of the research. Though Courtney has been an individual self-advocate for most of her life, these are all activities that foster collective self-advocacy. Making a distinction between individual and collective self-advocacy in inclusive research helps us to consider how inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities could assist others with intellectual disabilities in using self-advocacy skills while conducting inclusive research and the importance of building relationships with other inclusive research teams, especially when an inclusive researcher with intellectual disability is the only disabled researcher on the team. Courtney was in this position and did not know other inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities, so she had to figure out how to use her self-advocacy skills in the research independently. When inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities work with other researchers with intellectual disabilities or as part of a self-advocacy group (e.g., O’Brien et al. 2022; Flood et al. 2013; García Iriarte et al. 2023; Hopkins et al. 2022), their experiences may be different.

Courtney discussed how participating in inclusive research empowered her, developed her leadership skills, and increased her confidence to speak up and share her experiences and ideas, which in turn spurred on her growth as a self-advocate. Courtney’s experiences are very much in line with what the literature on inclusive research has suggested: self-advocacy skills are important for people with intellectual disabilities when they engage in inclusive research, and the process of inclusive research can empower them (O’Brien et al. 2022). Courtney’s experiences show that it is worthwhile to explicitly label and nurture self-advocacy skills in inclusive research, as they help to facilitate the process of inclusive research in addition to and beyond the development of research skills. Acknowledging Courtney’s self-advocacy skills also demonstrates how self-advocates bring their own skills to inclusive research, skills that they have acquired before receiving research training. Labeling self-advocacy skills also allows the field of inclusive research to recognize its interdependent relationship with self-advocacy and the way the histories and goals of inclusive research and self-advocacy are intertwined.

Lieke also wants to add to Courtney’s reflections that when Courtney shared her thoughts and needs, it also helped to improve the inclusive research. Not only did Courtney learn from Lieke, Lieke learned a lot from collaborating with Courtney as well. Our experiences are in line with the collaborative approach of inclusive research (Bigby et al. 2014a), and as described by García Iriarte et al. (2023) as well; as we got to know each other and both learned about inclusive research, Courtney became involved in more aspects of the research.

Plain Language Summary

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

7. Conclusions

Supporting people with intellectual disabilities in their (self-)advocacy is an important part of the definition of what inclusive research is (Walmsley et al. 2018). Inclusive research should be conducted and disseminated with awareness and intentions that promote the goals of self-advocates and self-advocacy movements. This includes an appreciation of its possibilities for collective action (Johnson 2009). Inclusive researchers should have more knowledge about the history of self-advocacy to be able to support it. The gap in the knowledge about the history of self-advocacy movements can be filled by inclusive research projects that center the experiences of self-advocates with intellectual disabilities as they share their own histories. Disseminating inclusive research to promote self-advocacy includes making the outcomes of inclusive research projects accessible (McCormack 2020). Inclusive researchers can explore the most effective formats and procedures for the accessible dissemination of research in collaboration with the disability community (Hopkins et al. 2022).

Inclusive researchers should also continue to consider the important role of self-advocacy as a requirement, a tool, and a product of inclusive research. This includes highlighting why self-advocacy skills are important for inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities, explicitly labeling the skills of inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities as self-advocacy skills, and supporting the development of individual and collective self-advocacy among researchers with intellectual disabilities throughout the inclusive research process. Additionally, it includes ensuring that the outcomes of inclusive research promote self-advocacy.

Inclusive researchers should discuss their experiences with self-advocacy in inclusive research in more detail and explicitly address the important relationship between self-advocacy and inclusive research. Moreover, inclusive researchers should look for ways to build connections between self-advocates and researchers to foster more engagement between these communities to increase the relevance and impact of inclusive research. For example, this may increase the reach of inclusive research to more people (O’Brien et al. 2022). Finally, the field should continue to critically examine the possibilities and challenges within research infrastructures, such as barriers to including and hiring researchers with intellectual disabilities (O’Brien et al. 2022).

Supporting self-advocacy among people with intellectual disabilities may hold potential for inclusive research in several ways. It can promote more community driven ‘bottom up’ inclusive research that is initiated by people with intellectual disabilities themselves. Additionally, it can serve to strengthen the pipeline of future inclusive researchers with intellectual disabilities. Finally, it can strengthen the relevance of inclusive research, as self-advocacy cannot only support people with intellectual disabilities to participate in research but also influence how the research is conducted and what it addresses.

Plain Language Summary

|  |

|  |

|  |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K., L.v.H. and C.v.d.H.; methodology, C.K., L.v.H., and C.v.d.H.; formal analysis, L.v.H., C.v.d.H., and C.K.; investigation, C.K., L.v.H., and C.v.d.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.v.H., C.v.d.H. and C.K.; writing—review and editing, L.v.H., C.v.d.H. and C.K.; supervision, L.v.H.; project administration, L.v.H.; funding acquisition, L.v.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Award Number NU27DD000021, funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Golisano Foundation. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Aaron Burdeen for sharing his experiences with self-advocacy which assisted us in the drafting of this article. We also want to acknowledge www.sclera.be (accessed on 26 November 2023) as the source for the pictograms used in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Administration for Community Living. 2023. State Councils on Developmental Disabilities. Administration for Community Living. Available online: http://acl.gov/programs/aging-and-disability-networks/state-councils-developmental-disabilities (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Aspis, Simone. 2002. Self-Advocacy: Vested Interests and Misunderstandings. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 30: 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of University Centers on Disabilities. n.d.a. ITAC: Self Advocates in LEND. Association of University Centers on Disabilities. Available online: https://www.aucd.org/itac/workgroups/self-advocates-in-lend (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Association of University Centers on Disabilities. n.d.b. UCEDD Resource Center—Consumer Advisory Committee. Association of University Centers on Disabilities. Available online: https://www.aucd.org/urc/Resources/Consumer-Advisory-Committee (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Atkinson, Dorothy. 2002. Self-advocacy and Research. In Advocacy and Learning Disability. Edited by Barry Gray and Robin Jackson. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 120–36. [Google Scholar]

- Beail, Nigel, and Katie Williams. 2014. Using Qualitative Methods in Research with People Who Have Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 27: 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigby, Christine, and Patsie Frawley. 2010. Reflections on Doing Inclusive Research in the ‘Making Life Good in the Community’ Study. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 35: 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigby, Christine, Patsie Frawley, and Paul Ramcharan. 2014a. A Collaborative Group Method of Inclusive Research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 27: 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigby, Christine, Patsie Frawley, and Paul Ramcharan. 2014b. Conceptualizing Inclusive Research with People with Intellectual Disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 27: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsdóttir, Kristin, and Aileen Soffia Svensdottir. 2008. Gambling for Capital: Learning Disability, Inclusive Research and Collaborative Life Histories. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 36: 263–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, Ian, and Jan Walmsley. 2006. Self-Advocacy in Historical Perspective. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 34: 133–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylov, Frank. 2006. Patterns of Culture Power after The Great Release: The History of Movements of Subculture Empowerment among Danish People with Learning Difficulties. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 34: 139–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, Joe. 2010. Leadership Development of Individuals with Developmental Disabilities in the Self-Advocacy Movement. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54: 1004–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callus, Anne-Marie, Isabel Bonello, and Brian Micallef. 2022. Advocacy and Self-advocacy in Malta: Reflections on the Lives of Maltese People with Intellectual Disability from the 1950s to the Present Day. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 50: 156–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, Allison C. 2009. On the Margins of Citizenship: Intellectual Disability and Civil Rights in Twentieth-Century America. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb34614.0001.001 (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Crombie Angus, Fionn, and Jonathan Angus. 2022. Exploring My Life Path by Asking 600 People What They Love about Theirs. Social Sciences 11: 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, Laura. 2019. BETWEEN AN ETHIC OF CARE AND AN ETHIC OF AUTONOMY: Negotiating Relational Autonomy, Disability, and Dependency. Angelaki: Journal of Theoretical Humanities 24: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haas, Catherine, Joanna Grace, Joanna Hope, and Melanie Nind. 2022. Doing Research Inclusively: Understanding What It Means to Do Research with and Alongside People with Profound Intellectual Disabilities. Social Sciences 11: 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorito, Claudio, Alessandro Bosco, Linda Birt, and Angela Hassiotis. 2018. Co-Research with Adults with Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31: 669–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embregts, Petri J. C. M., Elsbeth F. Taminiau, Luciënne Heerkens, Alice P. Schippers, and Geert van Hove. 2018. Collaboration in Inclusive Research: Competencies Considered Important for People with and without Intellectual Disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 15: 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Philip M. 2019. From Social Menace to Unfulfilled Promise: The Evolution of Policy and Practice towards People with Intellectual Disabilities in the United States. In Intellectual Disability in the Twentieth Century: Transnational Perspectives on People, Policy, and Practice. Edited by Jan Walmsley and Simon Jarrett. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, Samantha, Davey Bennett, Melissa Melsome, and Ruth Northway. 2013. Becoming a Researcher. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 41: 288–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frawley, Patsie, and Christine Bigby. 2015. Reflections on Being a First Generation Self-Advocate: Belonging, Social Connections, and Doing Things That Matter. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability 40: 254–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Mark, and Ruthie-Marie Beckwith. 2014. Self-Advocacy: The Emancipation Movement Led by People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. In Disability Incarcerated: Imprisonment and Disability in the United States and Canada. Edited by Liat Ben-Moshe, Chris Chapman and Allison C. Carey. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 237–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Iriarte, Edurne, Gemma Díaz Garolera, Nancy Salmon, Brian Donohoe, Greg Singleton, Laura Murray, Marie Dillon, Christina Burke, Nancy Leddin, Michael Sullivan, and et al. 2023. How We Work: Reflecting on Ten Years of Inclusive Research. Disability & Society 38: 205–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratt, Danielle, Kelley Johnson, Amanda Millear, Shaun Picken, Janice Slattery, and Jan Walmsley. 2022. Celebrating Thirty Years of Inclusive Research. Social Sciences 11: 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Golnaz, Peter Milley, Rosemary Lysaght, and Virginie Cobigo. 2023. Including People with Intellectual and Other Cognitive Disabilities in Research and Evaluation Teams: A Scoping Review of the Empirical Knowledge Base. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 17446295231189912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodley, Dan. 2000. Self-Advocacy in the Lives of People with Learning Difficulties: The Politics of Resilience. Buckingham: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, Mary F., and Tia Nelis. 2002. Self-Advocacy. In Embarking on a New Century: Mental Retardation at the End of the 20th Century. Edited by Robert L. Schalock, Pamela C. Baker and M. Doreen Croser. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation, pp. 221–34. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, David, and Christine Bigby. 2016. ‘We Were More Radical Back Then’: Victoria’s First Self-Advocacy Organisation for People with Intellectual Disability. Health and History 18: 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, Robert, Gerard Minogue, Joseph McGrath, Lisa J. Acheson, Pauline C. Skehan, Orla M. McMahon, and Brian Hogan. 2022. ‘Digging Deeper’ Advocate Researchers’ Views on Advocacy and Inclusive Research. Social Sciences 11: 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutton, Sue, Peter Park, Martin Levine, Shay Johnson, and Kosha Bramesfeld. 2017. Self-Advocacy from the Ashes of the Institution. Canadian Journal of Disability Studies 6: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Illinois Self-Advocacy Alliance. 2011. Resources. Illinois Self-Advocacy Alliance. April 20. Available online: https://selfadvocacyalliance.org/resources (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- James, Nancy S. 2014. Self-advocacy: Know Yourself, Know What You Need, Know How to Get It. Wrightslaw. January 17. Available online: https://www.wrightslaw.com/info/sec504.selfadvo.nancy.james.htm (accessed on 26 November 2023).

- Johnson, Kelley. 2009. No Longer Researching About Us Without Us: A Researcher’s Reflection on Rights and Inclusive Research in Ireland. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 37: 250–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahonde, Callista K. 2023. A Call to Give a Voice to People with Intellectual Disabilities in Africa through Inclusive Research. African Journal of Disability 12: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, Noelle. 2020. A Trip to the Caves: Making Life Story Work Inclusive and Accessible. In Belonging for People with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities. Edited by Melanie Nind and Iva Strnadová. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Katherine E., and Colleen A. Kidney. 2012. What Is Right? Ethics in Intellectual Disabilities Research. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities 9: 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulak, Magdalena, Sara Ryan, Pam Bebbington, Samantha Bennett, Jenny Carter, Lisa Davidson, Kathy Liddell, Angeli Vaid, and Charlotte Albury. 2022. “Ethno…graphy?!? I Can’t Even Say It”: Co-Designing Training for Ethnographic Research for People with Learning Disabilities and Carers. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 50: 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, Paul, and Patsie Frawley. 2019. From ‘on’ to ‘with’ to ‘by:’ People with a Learning Disability Creating a Space for the Third Wave of Inclusive Research. Qualitative Research 19: 382–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelis, Tia. 2018. Self-Advocacy Movement. In Disability in American Life: An Encyclopedia of Concepts, Policies, and Controversies. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, pp. 580–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Kim E. 2012. A Disability History of the United States. Revisioning American History. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nind, Melanie. 2016. Towards a Second Generation of Inclusive Research. In Inklusive Forschung. Edited by Tobias Buchner, Oliver Koenig and Saskia Schuppener. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt. [Google Scholar]

- Nind, Melanie, Rohhss Chapman, Jane Seale, and Liz Tilley. 2016. The Conundrum of Training and Capacity Building for People with Learning Disabilities Doing Research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 29: 542–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, Patricia, Edurne Garcia Iriarte, Roy Mc Conkey, Sarah Butler, and Bruce O’Brien. 2022. Inclusive Research and Intellectual Disabilities: Moving Forward on a Road Less Well-Travelled. Social Sciences 11: 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Driscoll, David, and Jan Walmsley. 2010. Absconding from Hospitals: A Means of Resistance? British Journal of Learning Disabilities 38: 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinele Martino, Alan, and Ann Fudge Schormans. 2018. When Good Intentions Backfire: University Research Ethics Review and the Intimate Lives of People Labeled with Intellectual Disabilities. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 19: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARTAC. 2023. Self-Advocacy. SARTAC. Available online: https://selfadvocacyinfo.org/self-advocacy/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Schwartz, Ariel E., Jessica M. Kramer, Ellen S. Cohn, and Katherine E. McDonald. 2019. ‘That Felt like Real Engagement’: Fostering and Maintaining Inclusive Research Collaborations with Individuals with Intellectual Disability. Qualitative Health Research 30: 236–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strnadová, Iva, and Jan Walmsley. 2018. Peer-Reviewed Articles on Inclusive Research: Do Co-Researchers with Intellectual Disabilities Have a Voice? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31: 132–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilley, Elizabeth, Iva Strnadová, Joanne Danker, Jan Walmsley, and Julie Loblinzk. 2020. The Impact of Self-Advocacy Organizations on the Subjective Well-Being of People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 33: 1151–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traustadottir, Rannveig. 2006. Learning about Self-Advocacy from Life History: A Case Study from the United States. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 34: 175–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuffrey-Wijne, Irene, Claire Kar Kei Lam, Daniel Marsden, Bernie Conway, Claire Harris, David Jeffrey, Leon Jordan, Richard Keagan-Bull, Michelle McDermott, Dan Newton, and et al. 2020. “Developing a Training Course to Teach Research Skills to People with Learning Disabilities: ‘It Gives Us a Voice. We CAN Be Researchers!’” British Journal of Learning Disabilities 48: 301–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- van Heumen, Lieke, Courtney Krueger, and Iulia Mihaila. 2024. The Development of a Co-Researcher: Training with and for People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 37: e13200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, Jan. 2001. Normalisation, Emancipatory Research and Inclusive Research in Learning Disability. Disability & Society 16: 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, Jan. 2014. Telling the History of Self-Advocacy: A Challenge for Inclusive Research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 27: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, Jan, and Kelley Johnson. 2003. Inclusive Research with People with Learning Disabilities Past, Present, and Futures. Philadelphia: J. Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Walmsley, Jan, Ian Davies, and Danielle Garratt. 2022. 50 Years of Speaking up in England—Towards an Important History. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 50: 208–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, Jan, Iva Strnadová, and Kelley Johnson. 2018. The Added Value of Inclusive Research. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31: 751–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltz, Mitzi, Karin van den Bosch, Hannah Ebben, Lineke van Hal, and Alice Schippers. 2015. Autism Self-Advocacy in the Netherlands: Past, Present and Future. Disability & Society 30: 1174–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehmeyer, Michael, Hank Bersani, and Ray Gagne. 2000. Riding the Third Wave: Self-Determination and Self-Advocacy in the 21st Century. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities 15: 106–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).