Abstract

A key feature of inclusive research is the accessibility of research procedures to meaningfully engage people with intellectual disabilities in research processes. Creating accessible research procedures requires innovations in methods traditionally used in research. This paper describes how the Lifeline Interview Method by Assink and Schroots was adapted and implemented in a study using life story research to better understand the experiences of older adults with intellectual disabilities. Twelve adults with intellectual disabilities over the age of 50 participated between two and seven times in interviews about their life histories. The interviewer assisted in the construction of timelines of key events in the participants’ individual life stories, and the participants decorated their lifelines throughout the course of the interviews. The lifeline process was an effective tool to engage the participants in the research process, support participation, and provide access for people with intellectual disabilities to retrieve their life experiences. Challenges in the lifeline process included barriers to gathering sufficient information to construct timelines and gatekeepers withholding access to information.

1. Introduction

1.1. Including People with Intellectual Disabilities in Research

The ability of people with intellectual disabilities to participate in research has traditionally been questioned, and much disability research has been conducted within an oppressive paradigm that conceptualizes disability as a problem and tragedy. Consequently, the voices of people with intellectual disabilities have long remained unheard, and other voices have been heard speaking for them (Atkinson and Walmsley 1999; Stone and Priestley 1996). Emancipatory approaches to disability research that engaged people with disabilities in research started to be articulated with the development of the social model of disability in the 1970s and 1980s (Stone and Priestley 1996). To bring the unknown about people with intellectual disabilities into the known and to provide information about their lives and experiences, research that included people with intellectual disabilities significantly increased in the 1990s (Beail and Williams 2014). This research used qualitative methods, as detailed below.

1.2. The Use of Qualitative Research Methods in Research with People with Intellectual Disabilities

Qualitative research methods are particularly well suited to collect data from people with intellectual disabilities, as their use is based on the assumption that all perspectives on an issue or event are inherently valuable and, potentially, credible and useful (Taylor and Bogdan 1998; Taylor et al. 1995). Qualitative methods have the potential to empower people with intellectual disabilities to insist that their experiences matter.

The first category of qualitative studies exploring the views and experiences of people with intellectual disabilities consisted of ethnographies and life histories that documented their lives (Grant and Ramcharan 2001). When conducting qualitative research with people with intellectual disabilities, the impact of an intellectual disability on participants’ ability to communicate does need to be considered, as does their ability to remember details about their lives (Beail and Williams 2014; Krisson et al. 2022; Vicari 2012). The challenge here is one of method (Booth and Booth 1996). Adaptations need to be made to qualitative research methods to enable people with intellectual disabilities to fully participate in research that addresses their lives and experiences (Booth and Booth 1996; Krisson et al. 2022). Creative and flexible research methods need to be developed that rely less on verbal communication or do not require verbal communication at all. Recent development of visual research methodologies has shown promise in empowering people with intellectual disabilities in research, for example, through using photographs, videos, and making drawings (Cluley 2017; Krisson et al. 2022; Rojas and Sanahuja 2012). Yet, more research is needed to explore and validate such inclusive research methods, an endeavor to which we aim to contribute with this paper (Krisson et al. 2022).

1.3. The Aim of This Paper

This paper reports on the development and implementation of a visual methodology to support life story research with older adults with intellectual disabilities through an adaptation of the Lifeline Interview Method by Assink and Schroots (2010). First, the paper provides a background on the application of life story research in bringing to light the experiences of people with intellectual disabilities and reviews considerations in using life story methodology with people with intellectual disabilities that helped inform this study. Then, the paper describes how the Lifeline Interview Method was adapted and how lifelines were used in a study with 12 older participants with intellectual disabilities. The paper concludes by analyzing the impact of using lifelines in research with people with intellectual disabilities and the implications of this work for future research.

2. Life Story Research

2.1. Life as a Story

Storytelling is a fundamental aspect of what it means to be human. People “story” their lives, who they are, and the world around them. Life stories are people’s accounts of their lives as a whole: past, present, and future; they allow people to feel as though their lives have a sense of unity and purpose and contain various scenes and scripts that together create a person’s identity (Basting 2009; Gubrium 2011; Kenyon and Randall 2001; McAdams 2001; Meininger 2001). Life stories do not develop in a vacuum. People’s lives are impacted by the structures and cultures of the societies they live in and the larger stories within those contexts. Structural dimensions such as social policies and distributions of power and wealth can constrain individuals as well as stunt their stories, silence their voices, and limit their sense of possibility (Gubrium 2011; Kenyon and Randall 2001; McAdams 2001). Sociocultural dimensions give meaning to what experiences are valued in societies, often creating disadvantages for both older and disabled people (Jönson and Taghizadeh Larsson 2021). Finally, people live their lives in networks of shared relationships, which means that stories exist to be shared with others and are shaped and entwined with other people’s stories and experiences (Gubrium 2011; Kenyon and Randall 2001; McAdams 2001).

Life stories are particularly important to older adults, as the longer their lives are, the more there is to tell (van Heumen 2021). The acknowledgement that how people feel about their lives is not only determined by what they experience today but also by what happened to them in the past and by their retrospective view on those life events has led to a body of research using the metaphor of life as story (McAdams 2001; Schroots and Birren 2001; Westerhof et al. 2001). Life story research has been adopted across disciplines as an umbrella term that includes different methodological approaches aimed at revealing the lives or segments of the lives of people. In addition to “life story research”, many different terms are used interchangeably, such as “life history work”, “biography”, “oral history”, “reminiscence”, “narrative analysis”, and “life review” (van Heumen 2021).

Gibson (2006) outlined the necessary approaches for researchers when undertaking life story research. They should listen actively and attend to the participants’ needs, be nonjudgmental, manage and be responsive to the participants’ expressions of emotion during the research, enjoy their stories, show interest in their past, and be disciplined about inserting themselves while being able to share their own thoughts if asked. Finally, researchers need to be able to reflect on and critically evaluate their own work and be able to accept feedback and offer feedback to others. These considerations are important for researchers who implement life story research with people with intellectual disabilities who have historically been marginalized in research and excluded from meaningful participation.

2.2. A Background on Life Story Research with People with Intellectual Disabilities

During the last 30 years, life story research has steadily become a prominent approach in research with people with intellectual disabilities, particularly in Europe (e.g., Atkinson et al. 2000; Atkinson et al. 1997; Atkinson and Walmsley 1999; Cadbury and Whitmore 2010; Goodley 1996; Hreinsdóttir et al. 2006; Hussain and Raczka 1997; Mee 2010; Roets et al. 2007; Roets et al. 2008; Roets and Van Hove 2003; Van Puyenbroeck and Maes 2004). Life story research with persons with intellectual disabilities has been mostly conducted through face-to-face interviews (Aspinall 2009). A life story of a person with an intellectual disability may chart an entire life or be a collection of small stories that express a person (Meininger 2006).

Three main perspectives undergird research conducted with the life stories of people with intellectual disabilities (Meininger 2003, 2005; Van Puyenbroeck and Maes 2008). In the critical approach, people with intellectual disabilities are supported to become aware of their past and take ownership of their life stories (Van Puyenbroeck and Maes 2008). The person-centered approach aims to inform individuals who provide everyday support about the needs of persons with an intellectual disability. This process consists of retelling and discussing life stories between people with intellectual disabilities, their family members, and staff and can include activities such as creating a life book (Aspinall 2009; Meininger 2003, 2005; van den Brandt-van Heek 2011; Van Puyenbroeck and Maes 2008). In the clinical approach, reminiscence is used as an alternative diagnostic instrument and counseling method for people with intellectual disabilities (Van Puyenbroeck and Maes 2008). The focus of this approach is not on empowerment but rather on dialectical understanding and relational intimacy.

Retrieving and sharing the life experiences of people with intellectual disabilities brings their disregarded lives to the foreground (Bornat 2002). Their life stories, like those of women, black people, and mental health survivors (Atkinson 2010), can recount their resilience and struggle against discrimination and exclusion (Goodley 1996; Hamilton and Atkinson 2009; Stefánsdóttir and Traustadóttir 2015). It can be empowering for people with intellectual disabilities to represent their own life experiences (Meininger 2006), and it can also allow for community building when common experiences are shared (Hamilton and Atkinson 2009). The process of sharing life stories may not only assist individuals with intellectual disabilities in processing difficult past life events, but it can also promote epistemological connections by highlighting the structures and forces through which people with intellectual disabilities have come to be seen as inferior. This process can highlight the impact of the social construction of intellectual disabilities on the everyday lives of people labeled as such (Hamilton and Atkinson 2009).

Much of the literature on life story research with people with intellectual disabilities reports on experiences of institutionalization (e.g., Cadbury and Whitmore 2010; Hamilton and Atkinson 2009; Hreinsdóttir et al. 2006; Mee 2010; Roets and Van Hove 2003), though many other topics such as community living and experiences with disability, relationships, and self-advocacy have been explored as well (Caldwell 2010; Lifshitz and Shahar 2022; Ledger et al. 2022). A small number of studies retrieved the experiences of adults with intellectual disabilities with aging (e.g., Burke et al. 2014; Brown and Gill 2009; David et al. 2015; Kåhlin et al. 2015; Neuman 2020). Life story research can provide important information about how older adults with intellectual disabilities experienced living with disabilities over time, how their earlier life experiences impact them today, and how they experience getting older (van Heumen 2021). Despite these important benefits of using life story research, there are challenges to implementing it with people with intellectual disabilities.

2.3. Challenges in Life Story Research with People with Intellectual Disabilities

One of the most important methodological issues in life story research concerns how to best collect information from people (Van Puyenbroeck and Maes 2008). Challenges include participants’ inarticulateness, unresponsiveness, and difficulties with the concept of time. These challenges are not unique to life story research with people who are labeled intellectually disabled but are more pronounced compared to life story research with people without this label (Atkinson and Walmsley 1999; Booth and Booth 1996; Schroots and Birren 2001). While strategies exist to address some of these challenges, they put limits on the important referential function of narrative, which is essentially a story in time (Booth and Booth 1996).

People with intellectual disabilities have little access to the written word and sometimes struggle with the spoken word as well (Atkinson et al. 1997). The concrete frame of reference typical for many people with intellectual disabilities can at times restrict their capacity to look back on their own lives with reflexivity (Booth and Booth 1996). People with intellectual disabilities may have some impairment of their memory and experience difficulty in providing details about their past, often confusing sequences of events (Aspinall 2009; Goodley 1996; Vicari 2012). They may also have a strong orientation toward the present and experience difficulties with dates, numbers, and the concept of time (Booth and Booth 1996; Sharp et al. 2001).

It has been argued that the challenges experienced by people with intellectual disabilities to understand time are indicative of lives that often lack the opportunities, life tasks, challenges, and milestones that people use to order their past and to mark the passage of time (Booth and Booth 1996). The implications of the challenges with time perception are less evident. It is unclear what the concept of time means to people with intellectual disabilities, whether they construct and structure their lives in chronological order of past–present–future, how they experience the present versus the past and the future, and whether they think and frame their lives in terms of stories.

Environmental influences impact the understanding of time, and it has been suggested that increasing the availability and reliability of external time cues in the immediate environment of persons with intellectual disabilities may improve time perception abilities (Owen and Wilson 2006). Owen and Wilson (2006) argue that time perception abilities are important as they “may reduce feelings of powerlessness and anxiety and increase feelings of self-efficacy and the individual’s sense of self as having a past, and a future” (p. 9).

Sources of bias are well documented within life story research as well. These include participants’ tendencies to misremember, rehearse a story, and/or, in some cases, lie. Checks for consistency between accounts of the same experience or event in different interviews have been one method suggested to address this bias (Goodley 1996). Additionally, oral historians have used personal stories alongside other sources of evidence (Manning 2010).

Finally, Goodley suggested that the question of whether people with intellectual disabilities are telling the “truth” when talking about their lives may be irrelevant (1996). It is more important to understand why people present their stories like they do. Ultimately, subjective experiences do not necessarily (need to) accurately reflect objective situations. This orientation is particularly important when it comes to life story research with people with intellectual disabilities, as they have historically been deemed “unreliable” research participants, and their perspectives have been dismissed.

Researchers have questioned how life story research is implemented with participants with intellectual disabilities. For example, as Henderson and Bigby (2017) aptly pointed out, almost every life story of a person with an intellectual disability is the result of a collaboration with an (often nondisabled) interviewer, with whom they have a unique relationship. The process of producing the life story through an interview tends to consist of a dialogue, but the product of the life story often takes the form of a monologue, centering the voice of the person with an intellectual disability. Henderson and Bigby (2017) warrant that attention needs to be paid closely to the process of amplifying the voice of people with intellectual disabilities in life story research and that delineating the roles played in the collaboration can promote self-reflexivity in this process. The ways in which researchers position themselves and reflect on their own functioning in the process of collecting, writing up, and presenting life stories are of crucial importance if they in any way strive toward an empowering approach (Goodley 1996). Additionally, there are important considerations of how to make the process of life story research more accessible for people with intellectual disabilities, as detailed below.

2.4. Making Life Story Research with People with Intellectual Disabilities More Accessible

Life story research is inherently inclusive, as it allows people to share their own stories. However, people with intellectual disabilities have had limited opportunities to share their life stories and to share in the stories of others like them in a way that is accessible to them. The acknowledgement that life story research is about more than the gathering of life stories and also includes the process of representing and sharing stories is particularly useful, as it acknowledges the importance of accessible dissemination of research that is about the lives of people with intellectual disabilities (McCormack 2020). Life stories of people with intellectual disabilities have almost exclusively been shared through text, such as books, articles, and reports, accessible to an audience with advanced literacy skills only (Aspinall 2009; Manning 2010).

Researchers have tried to develop strategies to make the process of life history research more inclusive and accessible for people with intellectual disabilities. Aspinall (2009) suggested that life stories be captured in different media, such as a photo album, an audio account, a video report, or a “memory box”, which contains objects to represent important memories, and recommended that the storyteller pick the medium. Aspinall also explored the use of multimedia life stories produced through computer technology. After working with a facilitator to retrieve and create the life story, persons with limited or no verbal communication presented their stories by pressing keys on a computer keyboard or another device. Aspinall advised that music and sounds can be included in multimedia life stories to make them an animated and personal experience. Finally, Aspinall observed that the design, presentation, and content of a life story can demonstrate the personality of the storyteller and that the storyteller should have full control over those elements of the life story. Manning (2010) also used digital storytelling to produce DVDs with text, sounds, and images to make the outcomes of life story research accessible for people with intellectual disabilities and of interest to a general audience.

McCormack (2020) conducted life story research with people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities and explored opportunities for storytelling in the broadest sense, including embodied stories (e.g., through performance, gestures, and muscle memory), sensory and visual stories (e.g., through photos and objects), and stories of places (e.g., through geographical locations and mobile interviewing conducted through situated talking while being on the move) (Brown and Durrheim 2009). McCormack combined creative life history research approaches (such as examining personal archive materials and conducting conversational interviews with allies) with ethnographic approaches (such as developing relationships with participants and learning to understand their communication) and immersed themselves in the lives of three people with disabilities and their circles of support for 18 months. McCormack describes the intersection of the communication strengths of participants with intellectual disabilities, of how their communication is supported, and of the location of their stories as “participatory life story spaces”. In these spaces, McCormack sees opportunities to support inclusive life story research. When life story materials are constant, it is the characteristics of people, time, and the environment that promote people with profound and multiple disabilities to engage actively with their past.

People with intellectual disabilities have traditionally not been fully included in life story research as co-interviewers and investigators (Caldwell 2010). Additionally, their participation in data analysis and theory development has been limited (Nind 2008; Koenig 2012). Koenig (2012) reported on a project that involved people with intellectual disabilities in a reference group (accompanied by support staff and research staff) to co-construct theory through the shared analysis of life stories. Activities during the meetings included short inputs and presentations by the facilitator, small and plenary group discussions, open spaces, and group exercises. One life story was analyzed per meeting, and various scaffolded techniques were used to engage people with intellectual disabilities in the analysis. More research is needed to determine how to best engage people with intellectual disabilities in the collection, analysis, and dissemination of life story research.

2.5. The Use of Lifelines in Life Story Research

Another tool that can be used to make life story research more accessible for people with intellectual disabilities is lifelines, a tool we explored in this study. Lifelines have been used as a life story methodology as early as the 1980s. Lifelines visually depict the life events of individuals in chronological order and can include interpretations of life events. In some studies using lifelines, participants draw and label their lifelines; in other studies, the researchers produce the lifelines. The lifeline can be triangulated with other data collection methods to confirm and complete a life story. As a life story research technique, lifelines are developed over time and require repeated contact with research participants (Gramling and Carr 2004). Lifelines have been used in various ways in research with vulnerable groups, such as women who smoke crack (Boyd et al. 1998), incarcerated women (Hanks and Carr 2008), and people in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (Dienstag 2003).

The Lifeline Interview Method (LIM), developed by Assink, Schroots, and colleagues, is a comprehensive approach to using lifelines in life story research. The LIM aids in understanding how individuals organize and review their behavior across their lives and uses the metaphor of life as a footpath, representing the life journey from birth to death. The LIM consists of a semi-structured interview and combines a quantitative and qualitative approach.

The lifeline in the LIM consists of a visual, two-dimensional representation of the course of a person’s life, with time on the horizontal axis and impact on the vertical axis. In a LIM session, the interviewer asks the participant to demonstrate their perceptions of life visually by drawing a line representing the time from birth to the present age. After the participant draws the lifeline, the participant labels each peak and each dip by chronological age and explains what happened at these moments. After visualizing and describing the past, the future is explored in the same manner. The result of this procedure is a lifeline consisting of a series of life events organized in a chronological manner, representing the life story. The LIM’s strength is its self-pacing quality and nondirective nature (Assink and Schroots 2010; Schroots and Birren 2001). Despite the perceived benefits and visual nature of this method, it has not yet been applied in life story research with people with intellectual disabilities. The section below discusses how this method was adapted and implemented in a study with older people with intellectual disabilities.

3. An Adaptation of the Lifeline Interview Method

3.1. Study Overview

The goal of this study was to gain insight into the experiences of older people with intellectual disabilities with their social relations across their lives. As part of the study, an adaptation of the Lifeline Interview Method was developed and tested (Assink and Schroots 2010; Schroots and Birren 2001). The Institutional Review Board of the university of the principal investigator approved the study. Recruitment occurred through service agencies for people with intellectual disabilities in a metropolitan area of the United States. Twelve adults with intellectual disabilities who were at least 50 years old (six men and six women) and lived in various residential settings (such as a family home, a group home, or an apartment) participated in between two and seven in-depth semi-structured qualitative interviews, during which their social network maps were completed (Tracy and Whittaker 1990) and their life histories were recorded.

The study was designed to first complete a life history interview with each participant and a key support person who was selected by the participant, followed by individual interviews with each participant, during which a lifeline was created. Lifelines placed life histories within a historical context and mapped the sequences of key life events in the individual life histories of the participants (Caldwell 2010). The lifelines also served as a visual cue for participants and assisted non-intrusively during the interviews. Each interview lasted between 30 min and 2 h, and the interviews were conducted several days to two weeks apart, within a period of a month to six weeks. The multiple contacts with participants over prolonged periods of time strengthened rapport (Mactavish et al. 2000; Taylor and Bogdan 1998).

The interview recordings were transcribed verbatim. The different stages of data collection resulted in interrelated data pieces: interview transcripts, field notes, social network maps, lifelines, and a journal, which explored the researcher’s experiences during the research to draw upon later for analysis. Data analysis started with a case analysis, which used all these data pieces (Patton 2002). The case analysis resulted in 12 individual life stories that provided context to the subsequent thematic analysis of the interview transcripts (Braun and Clarke 2006). Discussions of the events presented on the lifelines were included in the interview transcripts, but the lifelines were not independently analyzed as a source of data, for example, by coding or categorizing events placed on the lifelines. Rather, lifelines were used as a visual tool to support the interviews. The findings of the study are reported in detail elsewhere. A few key highlights are that parents and siblings played an important role in facilitating positive experiences in the early lives of the study participants. Participants’ lives were disrupted as they reached young and middle adulthood by life course transitions, such as moving out of family homes and the deaths of parents. Additionally, participants’ well-being was negatively impacted by distressing social encounters they experienced throughout their lives. Finally, participants’ social well-being in later life was characterized by parallel sentiments of longing and belonging.

3.2. Key Support Persons

Researchers have to make decisions about how to best retrieve information from people with intellectual disabilities in research and facilitate appropriate support for participation. This study carefully navigated this issue. The use of joint interviews with family or staff is a prevalent research strategy to supplement data gained from participants with intellectual disabilities or to provide a secondary or confirmatory source of information (Caldwell 2014). This technique can be problematic, as it has the potential for proxy or facilitated responses to suppress the voices of persons with intellectual disabilities (Caldwell 2014; Goodley 1997; Goodley and Rapley 2002; Rodgers 1999).

This study used the method of dyadic interviewing, as it carefully considered the selection and purpose of the involvement of a support person. A key feature of dyadic interviewing is that the participant with an intellectual disability identifies the key support person of their choice. According to Caldwell (2014, p. 11), this approach “removes an element of paternalism on the part of the researcher and facilitates the role of those individuals with intellectual disabilities in the research as having choice and a voice in how they are represented”. The strength of this approach is that it acknowledges interdependence as a central feature of human relationships (McCormack 2020). This acknowledgement allows for accommodations that facilitate the participation of people with intellectual disabilities in research (Caldwell 2014).

The study participants picked staff, family members, or friends who knew them well to support them during the study. One participant selected two key support persons. The nature of support and the level of involvement of each key support person differed, as each participant had different support needs and preferences throughout the research process. Two of the twelve participants in the study had guardians who served as key support persons (both siblings), and they decided to meet with the researcher first before any interviews with their family members with intellectual disabilities were conducted. Three participants decided to have the key support person present for all the interviews. Eight participants were only supported by their key support person during the first interviews and completed their work with the researcher independently. Only one participant opted not to have a key support person present at all for any of the interviews. The key support persons assisted with rephrasing questions, complementing or clarifying answers provided by the participants, and facilitating the overall communication. At times, the key support persons would also ask questions as part of naturally flowing conversations during interviews.

In some instances, research participation is only possible for people with intellectual disabilities when an ally occupies a position alongside them (McCormack 2020). The involvement of the key support persons was a key feature of this study’s successful implementation. Researchers need to be flexible to allow for a variety of different approaches with regard to the level and nature of involvement of a key support person, as individual support needs vary across participants.

Finally, researchers need to pay close attention to how the voices of people with intellectual disabilities are prioritized in life story research and what roles are occupied by those who are involved in life story research (Henderson and Bigby 2017). This study privileged the perspectives of the participants with intellectual disabilities in the results by sharing their stories from their perspectives and by including their direct quotes without correcting grammatical concerns in language, as often suggested researchers should do (Carlson 2010). The findings also included the distinctive views and experiences of the key support persons in the study to recognize their important roles in the lives of the participants and to acknowledge the interdependent relationships between participants and their key support persons.

3.3. Preparing for the Lifelines

To provide a starting point for the creation of lifelines, the researcher meticulously constructed vertical timelines of key events in the participants’ individual life stories by combining information that participants and key support persons provided during life story interviews and, if necessary and available, casefiles. The life story interview explored topics such as participants’ residential, educational, and employment histories, important life events, and experiences with social relations across their life course. Chronologies were ascertained in each life story by asking participants how old they were at the time of specific events, if certain life events happened before or after other events, or where they lived at the time of an event. The presence of key support persons during the life story interviews facilitated the retrieval of information about the participants’ pasts. However, most of the key support persons did not have intimate knowledge of the participants’ life histories. With the participants’ permission, information from case files provided additional information about their life histories. These files often contained minimal information or were incomplete. One agency did not allow viewing of any files, even though the participants, who were their own guardians, gave the project permission to do so. This raised the issue of ownership of information about the participants’ lives. In this instance, people with intellectual disabilities were not allowed to access information about their own lives and share it with people of their choosing. Such gatekeeping restrictions for people with intellectual disabilities by service providers are a common ethical challenge in research. The danger of overprotecting people with intellectual disabilities is that it may render them silent (Doody 2018; Witham et al. 2015). Researchers need to carefully navigate the involvement and concerns of gatekeepers as research is planned, conducted, and disseminated. This can include providing clear information on why the research is conducted, what it aims to accomplish, and what it involves.

3.4. Creating the Lifelines

The completed timelines of key events helped direct the remaining interviews with the participants, which explored their perspectives on their lives and enabled the creation of lifelines (with or without the presence of key support persons based on the participants’ preferences). Focusing on knowledge-based questions can confront people with cognitive impairments with challenges, as it requires reproducing facts from memory (van den Brandt-van Heek 2011). In order to make the process of creating the lifelines more accessible, it was important to retrieve the participants’ opinions and emotions surrounding life events and the people involved in them rather than exclusively focusing on facts related to those events. Each participant participated in the process of creating the lifeline differently and made different decisions in its creation regarding what life events they wanted to include and how they wanted to decorate it. As a result, each lifeline looked different. Only one participant did not have an interest in using the lifeline. The process did not seem to appeal to him. He was not sure what to write or draw. Even though the researcher rolled out the lifeline during two interviews, the participant did not use it. His direct support staff had not been able to find the photos he said he had in his room. Perhaps the use of pictures would have made the process appeal to him more. In this case, the timeline of key events was not decorated to support the interviews. Even without creating a lifeline, the participant was able to speak about his life experiences and complete the interviews.

This process of creating lifelines started with the drawing of a single horizontal line across the landscaped page on a piece of flipchart paper, with the birth year of the participant on the far left and the present year on the far right. With a pencil, the researcher marked the major life events discussed in previous interviews. In contrast to the original Lifeline Interview Method, no peaks or dips were drawn to visualize the negative and positive effects of life events, as this concept might have been too abstract for the participants.

As participants discussed various life events, they could choose whether they wanted to include them on their lifeline. This approach allowed participants to take ownership of the research process and decide how they wanted their story to be told. Participants decided both for and against the inclusion of certain life events on their lifelines based on what was most important to them, what they wanted to share, and how they wanted their experiences to be represented. Some participants decided not to include representations of particularly difficult events in their lives on their lifelines.

Participants also decided how they wanted their life events depicted on their lifelines. They had the additional option of writing or drawing something, and they were offered support with this when needed. Participants could decorate the empty paper using pens, markers, and pastels. Some participants chose to write or draw by themselves, while others asked for assistance. Life events were not necessarily discussed or placed on the lifelines in chronological order, and conversations flowed naturally while hopping back and forth in time. At times, the researcher or participants revisited life experiences across interviews to explore them in more detail.

Some participants and key support persons brought pictures and other personal artifacts, such as certificates, diplomas, and medals, to assist in communicating their life story in more detail. The artifacts served as visual cues and helped participants express their experiences, as prior research has also found (Caldwell 2010). Some participants included their pictures on their lifelines. The researcher explained to the participants that their lives would continue beyond the current year by gesturing toward the end of the lifeline and extending it by moving in an onward motion. This visualization helped participants express their desires for the future. To complete the construction of each lifeline, the researcher asked the participants if they wanted to give their lifeline a title. Some participants titled their lifeline, and others did not. After completing each lifeline, the researcher took a photograph for future analysis. One participant decided not to finish their lifeline.

Throughout the process of creating the lifelines, the meaning that various life events held for the participants could be explored effectively. The pace at which lifelines were created and completed varied across participants, as some needed more time than others to engage and share their experiences or share more details. Therefore, some participants engaged in more interview sessions than others to complete their lifelines. The repeated sessions built rapport and allowed for deep engagement with the participants’ experiences. The participants who created a lifeline all took ownership and kept it. Some participants showed their lifelines to their friends and staff and asked for them to be put on display. The next section provides an example of the process of creating a lifeline with its finished product, after which a reflection on the overall lifeline process follows.

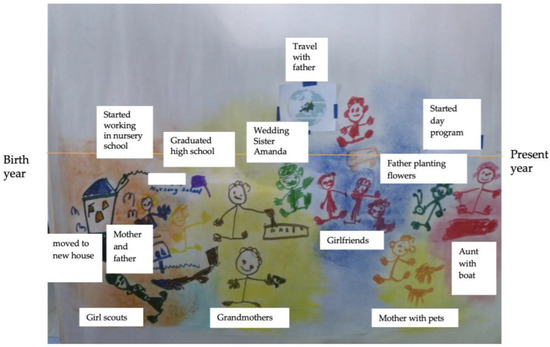

3.5. Example of a Lifeline

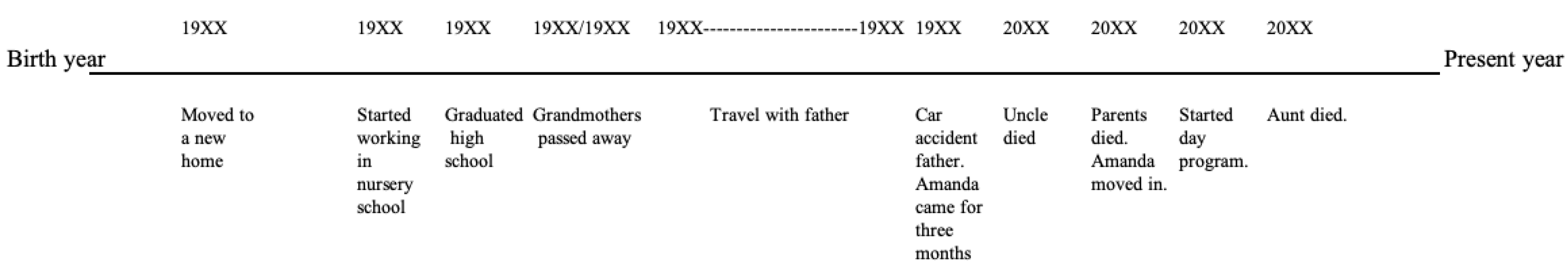

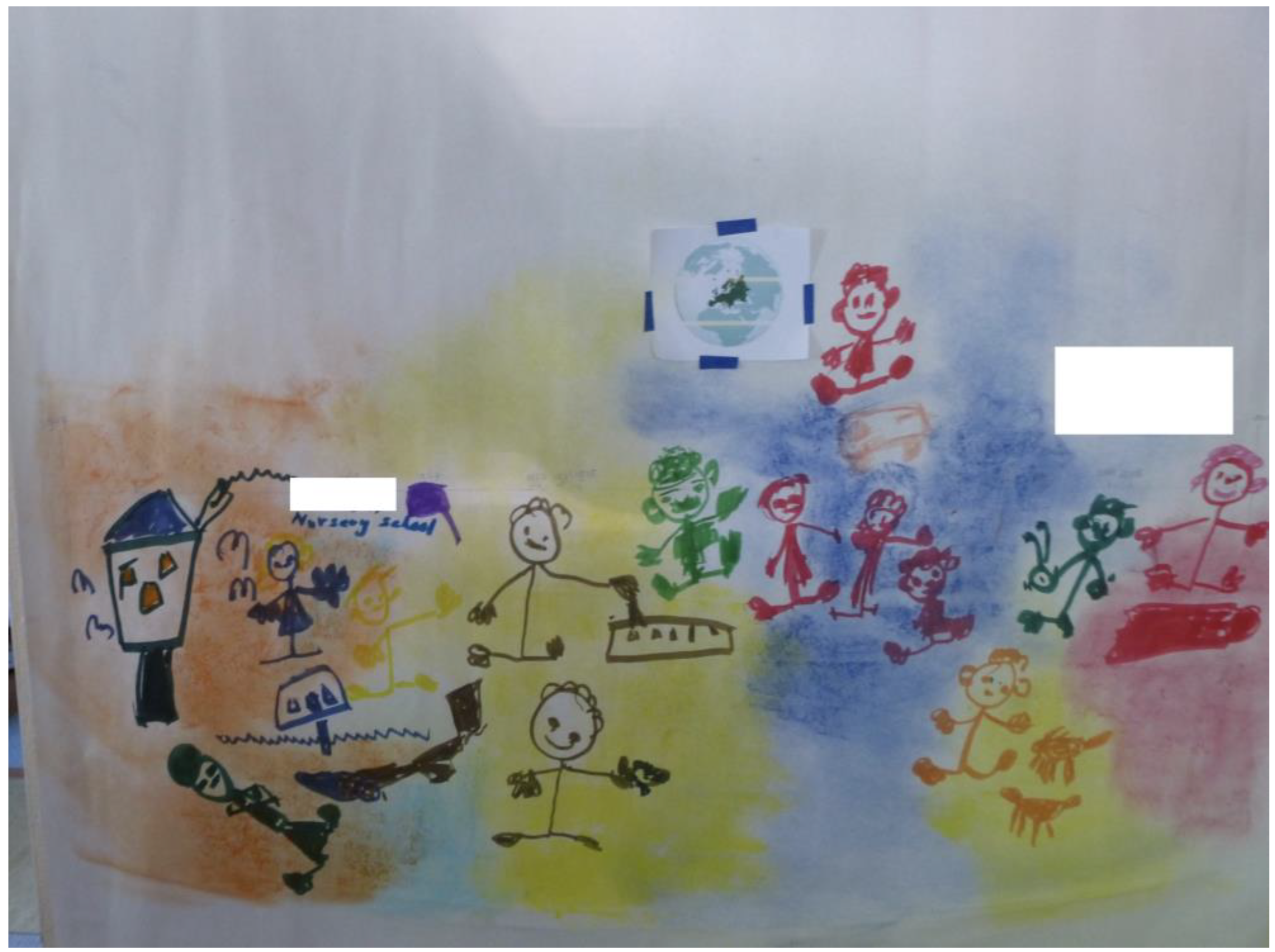

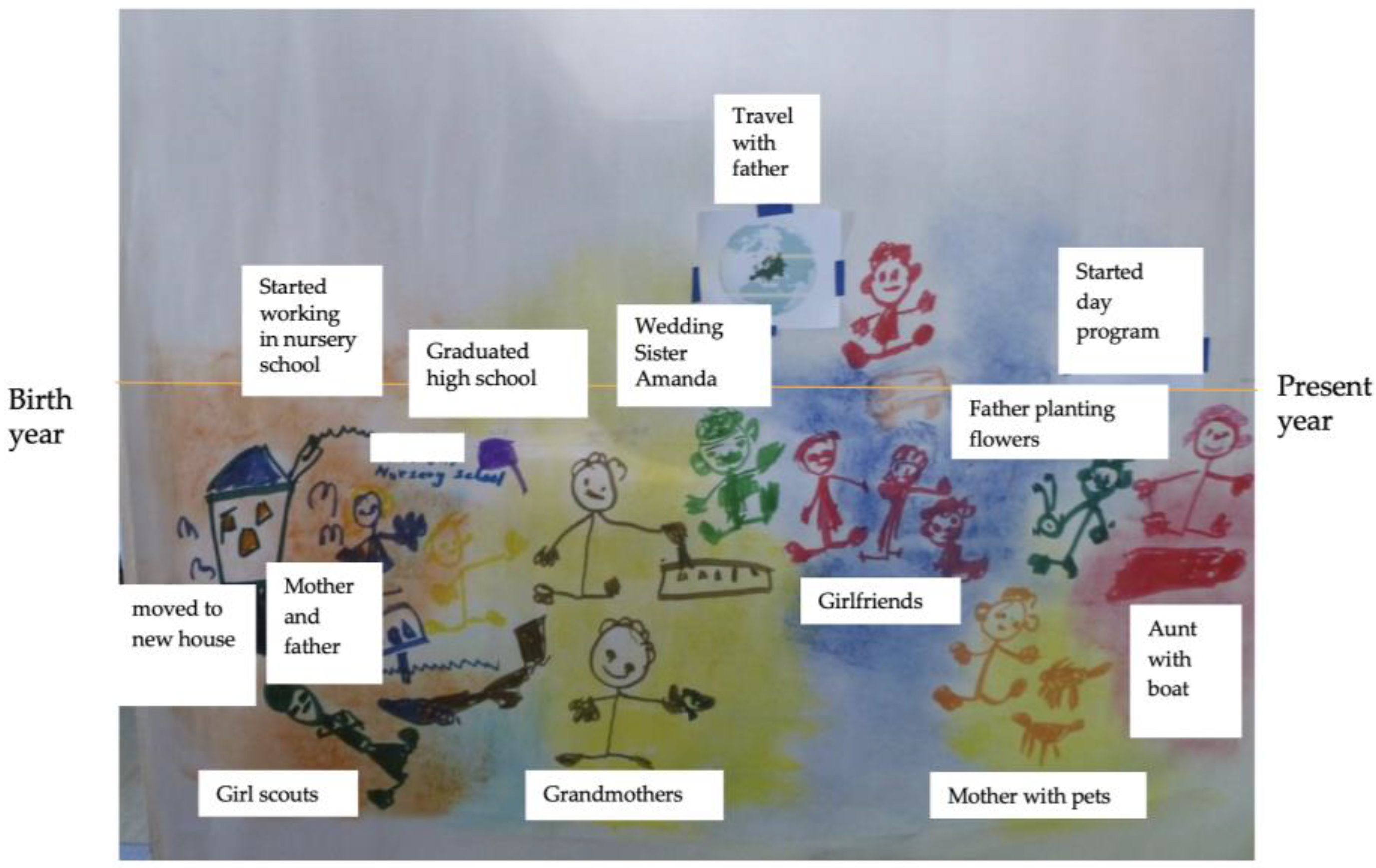

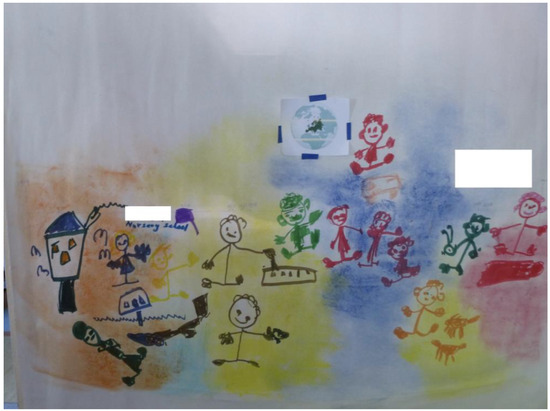

The story of Betty, a woman in her late sixties, provides an example of the process of creating a lifeline. Betty was one of the study participants and was supported to participate in the study by her sister and guardian, Amanda. Both names are randomly generated pseudonyms. Betty participated in four interviews, together with Amanda. The researcher had known Betty for several years and had interviewed her twice before. Throughout the interviews, Betty was extremely talkative and demonstrated that she had a very good memory. She recalled the names of all the children she played with in her neighborhood when she was a child. It was interesting to observe Betty remembering events that Amanda did not. In those instances, the conversations would turn into a family reminiscence session. Sometimes Betty would mention two events that happened decades apart in the same sentence. Amanda would clarify the chronologies. When Betty could not find the word she was looking for, she turned to Amanda for assistance. They finished each other’s sentences on several occasions. Amanda helped Betty answer questions, but when the researcher asked Betty a direct question regarding how she felt about something, Amanda gave Betty the space needed to provide her answer independently. Amanda supported and encouraged Betty to draw on her lifeline without taking over the process. After completing the life story interview together, the researcher created a vertical timeline of the key events in Betty’s life (Figure 1). After viewing some family photos, Betty decided to draw on her lifeline and not include these photos (see Figure 2 and Figure 3). She drew her house, the family’s lake cottage and boat, her mother and father, one grandmother playing the piano, one grandmother playing cards, her graduation cap, herself at her sister’s wedding, her three friends (who are her sister’s friends too), herself as a Girl Scout, the family car, and their two cats. She also wrote the name of the nursery school where she had worked on her lifeline. The inclusion of an image of the map of Europe provided a representation of the trips she took there with her father. She also included the logo of her workplace (removed from the lifeline pictures below for privacy reasons). Betty decided to complete her lifeline by shading the paper, so the result looked very colorful. Betty said she liked drawing on her lifeline. She was enthusiastic about adding drawings to her lifeline and would do so unprompted and then explain what she drew. Betty and Amanda gave permission for the use of photos of Betty’s lifeline below.

Figure 1.

Betty’s timeline of key events.

Figure 2.

Betty’s lifeline.

Figure 3.

Betty’s annotated lifeline.

3.6. Reflecting on the Lifeline Process

Even though the primary goal of using the lifelines was to provide a visual cue to support the interview process, the effort it took to create the timelines paid off in a number of less expected ways. Creating the lifelines was an interactive and empowering process that almost all participants actively engaged in. The work on the lifelines reduced tension during the interviews, built rapport, and helped the interaction between the researcher and the participants feel more natural and relaxed. Instead of questions being fired off while sitting on opposite ends of the table, the researcher and participants sat next to each other, both looking at the lifeline and collaborating in its creation. The participants seemed comfortable and excited during these meetings. Without being prompted, participants mentioned that they had a good time and had fun working on their lifelines and that they enjoyed seeing the researcher. Only one participant, though she did not offer negative feedback, decided not to complete her lifeline.

Participants decided for themselves what life experiences they wanted to include on their lifelines, which gave them ownership of the process and the representation of their lives. The lifeline process also provided participants with the freedom to express their experiences in a way of their choosing through drawing and writing, yet within a clear framework of the lifeline as a visual representation of their lives from birth to the present. Providing clear instructions to participants is important for visual research methodologies to be successful with participants with intellectual disabilities (Sigstad and Garrels 2021).

This study’s adaptation of the Lifeline Interview Method also allowed for engagement with participants’ experiences without asking for information that they were unable to provide. This is important because when participants experience a lack of mastery due to a gap between their ability and the demands of the research, they may not want to continue research participation (Sigstad and Garrels 2021). It is not effective to use research methodologies that emphasize participants’ limitations and make them feel inadequate (Booth and Booth 1996; van den Brandt-van Heek 2011). The role of key support persons was important in getting to know the participants and supporting them effectively in creating their lifelines. Involving the people around the participant is another important strategy for facilitating the research participation of people with intellectual disabilities (Cluley 2017).

The completed lifelines provided the participants with access to their memories and a sense of history about their own lives. The lifelines became a source of pride for them. The chronological review of their live events and the presentation of their lives seemed to be new experiences for a number of participants. The lifelines provided staff with new information about the participants’ lives as well. An important impact of life story research can be to offer those who provide everyday support more knowledge about the experiences and needs of people with intellectual disabilities (Aspinall 2009; Meininger 2003, 2005; van den Brandt-van Heek 2011; Van Puyenbroeck and Maes 2008).

4. Conclusions

The lifeline process was an effective tool to meaningfully involve and engage the participants in the research process and to retrieve their experiences. A few important adaptations were made to the original Lifeline Interview Method by Assink, Schroots, and colleagues (2010). Timelines were prepared with the assistance of key support persons before the lifelines were created. These timelines facilitated the creation of the lifelines in a way that did not rely on participants’ memories of what life events happened when and in which order. Additionally, only the horizontal axis of time was used on the lifelines, and the negative or positive impact of life experiences was explored verbally during the interviews. The process of creating the lifelines also consisted of non-verbal creative expressions of experiences through drawings and the inclusion of pictures.

In life story research, interviewers need to be critical of their own role in the research and their representation of the participants’ experiences (Henderson and Bigby 2017). Using the lifelines helped participants tell their own version of their lives by making their own decisions about which events and circumstances mattered to them in their lives and how they wanted them represented. This was particularly important with difficult life events, as participants were not forced to engage in memories they did not want to explore and discuss. The importance of this flexibility has been reported by other researchers as well, who indicated instances of participants with intellectual disabilities deciding not to include painful life events in the representation of their life histories (Atkinson 2010).

The lifelines provided participants with a clear, structured framework within which to represent their life experiences and assisted them in organizing their life story in chronological order (Atkinson 2010). Though life experiences during the interviews were not discussed in chronological order, the lifelines did rely on a chronological representation of time. This begs the question of to what extent instructions enabled participation and to what extent they restricted participation by prescribing participants to represent their lives as a chronological story, when that may not have been every participant’s preferred approach (Aspinall 2009). Researchers should ask the question of whether the structure provided by the lifeline process might limit some participants’ preferred storytelling methods. Future research on facilitating accessible and inclusive life story research with people with intellectual disabilities should explore this dilemma and consider diverse approaches to life story research.

Some participants with intellectual disabilities were not allowed access to information about their own lives to support their engagement in this study. Inclusion means information about the lives of people with intellectual disabilities should be theirs to access and share in ways of their choosing. The development of inclusive research enables more people with intellectual disabilities to participate in research, as well as it might facilitate research engagement becoming the expected norm and reduce instances of gatekeeping. Additionally, researchers should reflect in their reports on examples of gatekeeping so the field can explore effective solutions to reduce this barrier and better include people with intellectual disabilities in research. Researchers also need to grapple with limited access to and availability of information about participants’ lives and discuss the implications of this reality when conducting life story research with people with intellectual disabilities.

The aim of this study was to develop and implement an adaptation of the Lifeline Interview Method by Assink and Schroots (2010). At this stage, participants were not explicitly asked about their experiences with creating their lifelines, and consequently, the interpretations of the process reported here are those of the nondisabled researcher. Future research should expand by evaluating how participants experienced the lifeline process and detailing their perspectives on the method’s usefulness.

Additionally, further research should explore how to make all stages of life story research more inclusive and involve people with intellectual disabilities as facilitators and interviewers. This study’s adaptation of the Lifeline Interview Method holds potential as an accessible tool not only for research participants but also for people with intellectual disabilities as co-researchers. Implementing this tool with research participants consists of a number of concrete steps, such as providing them with creative materials and engaging them in a process of including events and experiences and making additions to their lifelines. An accessible facilitator guide could support co-researchers with intellectual disabilities in leading this process.

This study’s use of lifelines still relied on participants’ verbal communication skills to some extent. We need to continue to explore visual methodologies that respond to a wide variety of skill levels, abilities, and interests of participants with intellectual disabilities. Finally, future research should also explore the use of lifelines as a visual tool to disseminate results and make the outcomes of life history research more accessible (Aspinall 2009; Manning 2010; McCormack 2020).

In exploring accessible life story methodology for research, we should not overlook the potential impact that exploring life stories can have in the everyday lives of people with intellectual disabilities. These stories are sometimes lost, especially when support is needed to retain and access memories (Gillman et al. 1997). Retrieving life stories can have a positive impact by facilitating reminiscence among people with intellectual disabilities as they grow older and by increasing understanding of their life experiences among those who support them. With more knowledge about the perspectives of people with intellectual disabilities, their needs can be better supported (Ledger et al. 2022).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.v.H.; methodology, L.v.H.; formal analysis, L.v.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.v.H.; writing—review and editing, L.v.H. and T.H.; project administration, L.v.H.; funding acquisition, L.v.H. and T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The contents of this article were developed under a grant from the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Community Living (ACL), National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) Grant # 90AR5007-02-00. However, this research does not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), and readers should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. Additional funding from the University of Illinois Chicago supported this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois Chicago (protocol #2013-1225, 11 April 2014).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aspinall, Ann. 2009. Creativity, choice and control: The use of multimedia life story work as a tool to facilitate access. In Understanding and Promoting Access for People with Learning Difficulties. London: Routledge, pp. 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Assink, Marian H. J., and Johannes J. F. Schroots. 2010. The Dynamics of Autobiographical Memory: Using the LIM, Lifeline Interview Method. Cambridge: Hogrefe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Dorothy. 2010. Narratives and people with learning disabilities. In Learning Disability: A Life Cycle Approach (Second Edition). Edited by Gordon Grant, Paul Ramcharan, Margaret Flynn and Malcolm Richardson. Maidenhead: Open University Press/McGraw Hill Education, pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Dorothy, and Jan Walmsley. 1999. Using autobiographical approaches with people with learning difficulties. Disability & Society 14: 203–16. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Dorothy, Mark Jackson, and Jan Walmsley. 1997. Forgotten Lives: Exploring the History of Learning Disability. Birmingham: BILD Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, Dorothy, Micelle McCarthy, Jan Walmsley, Mabel Cooper, Sheena Rolph, Simone Aspis, Pam Barette, Mary Coventry, and Gloria Ferris. 2000. Good Times, Bad Times: Women with Learning Difficulties Telling Their Stories. Birmingham: BILD publications. [Google Scholar]

- Basting, Anne Davis. 2009. Forget Memory: Creating Better Lives for People with Dementia. Baltimore: JHU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beail, Nigel, and Katie Williams. 2014. Using qualitative methods in research with people who have intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 27: 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Tim, and Wendy Booth. 1996. Sounds of silence: Narrative research with inarticulate subjects. Disability & Society 11: 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bornat, Joanna. 2002. Doing life history research. In Researching Ageing and Later Life: The Practice of Social Gerontology. Edited by Annie Jamieson and Christina R. Victor. Buckingham: Open University Press, pp. 117–34. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Carol J., Elizabeth Hill, Carolyn Holmes, and Rogaire Purnell. 1998. Putting drug use in context: Life-lines of African American women who smoke crack. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 15: 235–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Allison A., and Carol J. Gill. 2009. New voices in women’s health: Perceptions of women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 47: 337–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Lyndsay, and Kevin Durrheim. 2009. Different kinds of knowing: Generating qualitative data through mobile interviewing. Qualitative Inquiry 15: 911–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Eilish, Mary McCarron, Rachael Carroll, Eimear McGlinchey, and Philip McCallion. 2014. What it’s like to grow older: The aging perceptions of people with an intellectual disability in Ireland. Mental Retardation 52: 205–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadbury, Heather, and Michelle Whitmore. 2010. Spending time in Normansfield: Changes in the day to day life of Patricia Collen. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 38: 120–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, Joe. 2010. Leadership development of individuals with developmental disabilities in the self-advocacy movement. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 54: 1004–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, Kate. 2014. Dyadic interviewing: A technique valuing interdependence in interviews with individuals with intellectual disabilities. Qualitative Research 14: 488–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, Julie A. 2010. Avoiding traps in member checking. Qualitative Report 15: 1102–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluley, Victoria. 2017. Using photovoice to include people with profound and multiple learning disabilities in inclusive research. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 45: 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, Niry, Ilana Duvdevani, and Israel Doron. 2015. Older women with intellectual disability and the meaning of aging. Journal of Women & Aging 27: 216–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienstag, Alan. 2003. Lessons from the Lifelines Writing Group for People in the Early Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease: Forgetting that We Don’t Remember. In Mental Wellness in Aging: Strengths-Based Approaches. Edited by Judah L. Ronch and Joseph A. Goldfield. Baltimore: Health Professions Press, pp. 343–52. [Google Scholar]

- Doody, Owen. 2018. Ethical challenges in intellectual disability research. Mathews Journal of Nursing and Health Care 1: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Faith. 2006. Reminiscence and Recall-A Practical Guide to Reminiscence Work. London: Age Concern. [Google Scholar]

- Gillman, Maureen, John Swain, and Bob Heyman. 1997. Life history or ‘case’history: The objectification of people with learning difficulties through the tyranny of professional discourses. Disability & Society 12: 675–94. [Google Scholar]

- Goodley, Dan. 1997. Locating self-advocacy in models of disability: Understanding disability in the support of self-advocates with learning difficulties. Disability & Society 12: 367–79. [Google Scholar]

- Goodley, Dan, and Mark Rapley. 2002. Changing the Subject: Postmodernity and People with Learning Difficulties. In Disability/postmodernity: Embodying Disability Theory. Edited by Mairian Corker and Tom Shakespeare. London: Continuum, pp. 127–42. [Google Scholar]

- Goodley, Danny. 1996. Tales of hidden lives: A critical examination of life history research with people who have learning difficulties. Disability & Society 11: 333–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gramling, Lou F., and Rebecca L. Carr. 2004. Lifelines: A life history methodology. Nursing Research 53: 207–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Gordon, and Paul Ramcharan. 2001. Views and experiences of people with intellectual disabilities and their families. (2) The family perspective. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 14: 364–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubrium, Jaber F. 2011. Narrative events and biographical construction in old age. In Storying Later Life: Issues, Investigations, and Interventions in Narrative Gerontology. Edited by Gary Kenyon, Ernst Bohlmeijer and William L. Randall. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, Carol, and Dorothy Atkinson. 2009. ‘A Story to Tell’: Learning from the life-stories of older people with intellectual disabilities in Ireland. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 37: 316–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, Roma Stovall, and Nicole T. Carr. 2008. Lifelines of women in jail as self-constructed visual probes for life history research. Marriage & Family Review 42: 105–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, David, and Christine Bigby. 2017. Whose life story is it? Self-reflexive life story research with people with intellectual disabilities. The Oral History Review 44: 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hreinsdóttir, Eygló Ebba, Guðrún Stefánsdóttir, Anne Lewthwaite, Sue Ledger, and Lindy Shufflebotham. 2006. Is my story so different from yours? Comparing life stories, experiences of institutionalization and self-advocacy in England and Iceland. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 34: 157–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Feryad, and Roman Raczka. 1997. Life story work for people with learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 25: 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönson, Håkan, and Annika Taghizadeh Larsson. 2021. Ableism and Ageism. In Encyclopedia of Gerontology and Population Aging. Edited by Danan Gu and Matthew E. Dupre. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kåhlin, Ida, Anette Kjellberg, Catharina Nord, and Jan-Erik Hagberg. 2015. Lived experiences of ageing and later life in older people with intellectual disabilities. Ageing & Society 35: 602–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, Gary M., and William L. Randall. 2001. Narrative Gerontology: An Overview. In Narrative Gerontology: Theory, Research and Practice. Edited by Gary M. Kenyon, Phillip Clark and Brian de Vries. New York: Springer Publishing Company, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Oliver. 2012. Any added value? Co-constructing life stories of and with people with intellectual disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 40: 213–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisson, Emma, Maria Qureshi, and Annabel Head. 2022. Adapting photovoice to explore identity expression amongst people with intellectual disabilities who have limited or no verbal communication. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 50: 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, Sue, Noelle McCormack, Jan Walmsley, Elizabeth Tilley, and Ian Davies. 2022. “Everyone has a story to tell”: A review of life stories in learning disability research and practice. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 50: 484–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifshitz, Hefziba, and Ayelet Shahar. 2022. Life Story Narratives of Adults with Intellectual Disability and Mental Health Problems: Personal Identity, Quality of Life and Future Orientation. The Qualitative Report 27: 2839–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mactavish, Jennifer B., Michael J. Mahon, and Zana Marie Lutfiyya. 2000. ‘I can speak for myself’: Involving individuals with intellectual disabilities as research participants. Mental Retardation 38: 216–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manning, Corinne. 2010. ‘My memory’s back!’ Inclusive learning disability research using ethics, oral history and digital storytelling. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 38: 160–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, Dan P. 2001. The psychology of life stories. Review of General Psychology 5: 100–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, Noelle. 2020. A trip to the caves: Making life story work inclusive and accessible. In Belonging for People with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities. London: Routledge, pp. 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mee, Steve. 2010. You’re not to dance with the girls: Oral history, changing perception and practice. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 14: 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meininger, Herman P. 2001. Autonomy and professional responsibility in care for persons with intellectual disabilities. Nursing Philosophy 2: 240–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meininger, Herman P. 2003. Werken met levensverhalen: Een narratief-ethische verkenning. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Zorg aan Mensen met Verstandelijke Beperkingen 2: 102–19. [Google Scholar]

- Meininger, Herman P. 2005. Narrative ethics in nursing for persons with intellectual disabilities 1. Nursing Philosophy 6: 106–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meininger, Herman P. 2006. Narrating, writing, reading: Life story work as an aid to (self) advocacy. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 34: 181–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, Ran. 2020. The life journeys of adults with intellectual and developmental Disabilities: Implications for a new model of holistic supports. Journal of Social Service Research 47: 327–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nind, Melanie. 2008. Conducting qualitative research with people with learning, communication and other disabilities: Methodological challenges. National Centre for Research Methods. Available online: https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/491/1/MethodsReviewPaperNCRM-012.pdf (accessed on 4 February 2024).

- Owen, Ann L., and Rebecca R. Wilson. 2006. Unlocking the riddle of time in learning disability. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 10: 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, Jackie. 1999. Trying to get it right: Undertaking research involving people with learning difficulties. Disability & Society 14: 421–33. [Google Scholar]

- Roets, Griet, and Geert Van Hove. 2003. The story of Belle, Minnie, Louise and the Sovjets: Throwing light on the dark side of an institution. Disability & Society 18: 599–624. [Google Scholar]

- Roets, Griet, Dan Goodley, and Geert van Hove. 2007. Narrative in a nutshell: Sharing hopes, fears, and dreams with self-advocates. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities 45: 323–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roets, Griet, Rosa Reinaart, and Geert van Hove. 2008. Living between borderlands: Discovering a sense of nomadic subjectivity throughout Rosa’s life story. Journal of Gender Studies 17: 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, Susana, and Josep Mª Sanahuja. 2012. The image as a relate: Video as a resource for listening to and giving voice to persons with learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities 40: 31–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroots, J. J., and James E. Birren. 2001. The Study of Lives in Progress: Approaches to Research on Life Stories. In Qualitative Gerontology: Perspectives for a New Century. Edited by Graham D. Rowles and Nancy E. Schoenberg. New York: Springer Publishing Company, pp. 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, Kirsten, George C. Murray, Karen McKenzie, April Quigley, and Shona Patrick. 2001. A Matter of Time. Learning Disability Practice 3: 10–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigstad, Hanne Marie Høybråten, and Veerle Garrels. 2021. A semi-structured approach to photo elicitation methodology for research participants with intellectual disability. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 16094069211027057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefánsdóttir, Guðrún V., and Rannveig Traustadóttir. 2015. Life histories as counter-narratives against dominant and negative stereotypes about people with intellectual disabilities. Disability & Society 30: 368–80. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, Emma, and Mark Priestley. 1996. Parasites, pawns and partners: Disability research and the role of non-disabled researchers. The British Journal of Sociology 47: 699–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Steven J., and Robert Bogdan. 1998. Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: A Guidebook and Resource. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Steven J., Robert Bogdan, and Zana Marie Lutfiyya. 1995. The Variety of Community Experience: Qualitative Studies of Family and Community Life. Baltimore: P.H. Brooks Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, Elizabeth M., and James K. Whittaker. 1990. The social network map: Assessing social support in clinical practice. Families in Society 71: 461–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brandt-van Heek, Marie-Elise. 2011. Asking the right questions: Enabling persons with dementia to speak for themselves. In Storying Later Life. Issues, Investigations and Interventions in Narrative Gerontology. Edited by Gary Kenyon, Ernst Bohlmeijer and William L. Randall. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 338–53. [Google Scholar]

- van Heumen, Lieke. 2021. Ageing with Lifelong Disability: Individual Meanings and Experiences Over Time. In Handbook on Ageing with Disability. Edited by Michelle Putnam and Christine Bigby. New York: Routledge, pp. 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Van Puyenbroeck, Joris, and Beatrijs Maes. 2004. De betekenis van reminiscentie in de begeleiding van ouder wordende mensen met verstandelijke beperkingen: Een kwalitatieve verkenning. Nederlands Tijdschrift voor de Zorg aan Mensen met Verstandelijke Beperkingen 30: 146–65. [Google Scholar]

- Van Puyenbroeck, Joris, and Beatrijs Maes. 2008. A review of critical, person-centred and clinical approaches to reminiscence work for people with intellectual disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 55: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicari, Stefano. 2012. Memory and learning intellectual disabilities. In The Oxford Handbook of Intellectual Disability and Development. Edited by Jacob A. Burack, Robert M. Hodapp, Grace Iarocci and Eward Zigler. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof, Gerben J., Freya Dittmann-Kohli, and Toine Thissen. 2001. Beyond life satisfaction: Lay conceptions of well-being among middle-aged and elderly adults. Social Indicators Research 56: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witham, Gary, Anna Beddow, and Carol Haigh. 2015. Reflections on access: Too vulnerable to research? Journal of Research in Nursing 20: 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).