1. Introduction: Marketing Culture

Culture can be marketed. This applies not only to the tourism sector, but also to design, art, and spirituality as in the case of the tattoo art Sak Yant. On the one hand, the phenomenon of marketable culture is viewed positively: “marketing of culture and heritage products links to sustainable identity, economy and destination viability” (

Brown and Cave 2010, p. 87). On the other hand, aspects of marketed culture can be altered by this very fact: as “airport art” shows, for example, cultural elements are adapted to the tastes and possibilities of tourists, varying traditional patterns, substituting traditional materials, or changing traditional techniques towards mass production. This way, some people—often the rich and powerful, and also often people belonging to different cultural contexts—particularly benefit from cultural elements. Further, the value structure around cultural elements can also fundamentally change through their transformation into a cross-cultural commodity (

Zhou 2021).

Thus, this article is addressing the question of cultural appropriation, accompanied by the question of how the art of Sak Yant fits into the bias of spirituality and embodiment and why this seems to exert a special fascination in “Westerners”.

When it comes to the research used, various clusters are identifiable. One basis evolves around “cultural appropriation” as a central term of the article (e.g.,

Jackson 2021;

Young 2010) and aims at identifying factors that set appropriation apart from appreciation. Then, reserach on tattooing as a central social practice will be considered, with a focus on the motivations of the tattooees (e.g.,

Kalanj-Mizzi et al. 2018;

Anderson and Sansone 2003;

Tiggemann and Golder 2006;

Anderson and Sansone 2003). Other research looks at social media with regard to communication, identity, and marketing (e.g.,

Dyer 2020;

Borup 2020), and then, there are of course texts that are concerned with Hindu–Buddhist traditions (e.g.,

Chansanam et al. 2021;

Cook 2007;

Vater 2011). When it comes to Sak Yants in particular, social media quotes will be used to illustrate the meanings assigned and the way they are communicated (also) to “Westerners”.

2. The “West” and the “Rest”

“In the contemporary world, individuals from rich and powerful majority cultures often appropriate from disadvantaged indigenous and minority cultures” (

Young 2010, p. ix). Usually, the bias mostly concerns “the West and the rest”. Therefore, it is important to find a working definition for the frequently used term the “West”, even though it seems like an impossible endeavour. The term “West” is derived from the geographical field; however, one can neither determine geographical areas that would be clearly included or excluded in the term, as the direction depends on one’s own location, nor refer to specific artefacts, traditions, spiritualities, or attitudes that would be clearly tied to it. Migration, diasporas, and global (sub)cultures add to the fuzziness.

Yet, obviously, the binary concept underlying the term is based on a way of thinking that distinguishes ontologically and epistemologically between the “West” and the rest, that is, e.g., what is described as the “Orient” (

Said 1978, p. 11) and is often represented as a “closed system” (

Said 1978, p. 70), “reduced to a timeless essence” (

Carrier 1995, p. 2) and constitutes an antithesis of the West. Edward Said has famously formulated “a theory of artistic imperialism and its relationship to power and the imagination” (

Sellers-Young 2013, p. 3). This is the context in which the mental recolonization of geographic areas and people that earlier had already suffered from colonialism takes place by imposing images onto them, for example, images of wildness and exoticism (

Viveiros de Castro 2002, p. 351) in contrast to the “West”. Therefore, the term “West” is not only hard to define, but also carries some baggage, as discussed by

Bruno Latour (

2007, p. 18; see also

Mathieu 2022, for a reflection on Descola’s position); however, there is no real alternative to the term, so it is still frequently used both in political and social contexts, as well as in scientific works.

3. Cultural Appropriation

Based on the idea of a difference between conditions in the “West” and the “rest”, cultural appropriation has become a buzzword in both popular, as well as academic discourse and is used in various disciplines, such as ethnology (

Jackson 2021), communication science (

Rogers 2006), politics (

Lalonde 2019), or philosophy (

Matthes 2019). Lalonde mentions three criteria for cultural appropriation: nonrecognition, misrecognition, and exploitation (

Lalonde 2019, p. 329). Any one of these would suffice, but they are often combined. Thus, what is important here is not only the fact that the “West” is taking ideas, artefacts, practices, etc., that belong to other cultures, but, maybe even more relevant, is who benefits from it and, connected to this, how the appropriation is communicated and whether cultural elements are attributed correctly. Kim Kardashian is a famous example for giving wrong credits again and again: she has been wearing a hairstyle known as cornrows or Fulani braids, originating from the Fula tribes in West Africa. However, Kardashian called it “Bo Derek braids”, attributing it to Bo Derek, a blonde sex symbol of the 1980s. The blogger Nardos sees in the renaming and misattribution an illegitimate recontextualization: “It is no problem if the self-declared trendsetter Mrs Kardashian West is getting braids […] The problem was in the way of mediation. Not only does she show off her hairstyle as if it was her own creation, but she renames it as well” (

Nardos 2018). Further, she has been wearing a typical South Asian bridal headpiece, the Maang Tikka, to a church, combining it with a white dress, a colour that in South Asia is usually worn for funerals. Earlier, she had stated that Indian food was “disgusting” (

Rae 2021), which was seen as a sign that she “clearly doesn’t appreciate the culture” (@malee._.hah cited in

Rae 2021).

Yet, getting inspired by and thus eventually benefiting from other cultures has probably been a cultural universal for a very long time, and also a driving force in creativity. Dogon masks famously inspired Pablo Picasso to develop Cubism, the Jugendstil painters turned to Japanese art to find inspiration, and fashion designers, both haute couture and mainstream, use foreign patterns and cuts to develop new ideas. In principle, cultural exchange is a basic constant of human development. In many cases, the driving force may not be the wish to appropriate, but admiration followed by the wish to become part of something. However, this still becomes critical if there is a power imbalance, if disadvantaged groups do not receive any remuneration in the form of direct or indirect financial outcome and/or increased status through the right credits (

Kennedy and Makkar 2021, p. 155f.), and if central values of a culture are touched and the appropriated items get transformed into completely different value systems, i.e., if misrecognition takes place (e.g., as discussed for a song by Beyoncé with regard to African aesthetics,

Welang 2023, p. 153).

In the case of Sak Yant, cultural appropriation could be seen as particularly serious, because we deal with a context that incorporates spiritual aspects, which makes cultural appropriation even more explosive: values that form the core of a culture may not be understood in their depth by people from another cultural context, may be reinterpreted, or there may be no interest in understanding them at all, reducing them to their visual quality, marketable on Instagram.

4. Introduction: Sak Yant

Tattoos can be seen as “a complete emotion, incorporating myths and beliefs, which have played important and diverse roles in society since the dawn of humankind” (

Ghosh 2020, p. 295). This description seems to apply to Sak Yant tattoos in particular. The art of Sak Yant originates from Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia and is getting increasingly popular among non-Buddhist “Westerners” (

May 2014, p. 3), to the point that “tourist agencies even offer tours to authentic temples where you can get your Sak Yant” (

Cara n.d.). A trigger may have been that about 20 years ago, Angelina Jolie “showed off her first Thai tattoo” and “raised the country’s international status for spiritual tattoos” (

Nieset 2018). Further, and even global popularity was gained via movies such as the blockbuster Jom Kha Mung Wej “The Necromancer” (2005), in which the tattoos are related to magical powers like being impervious to bullets (

Cook 2007, p. 24).

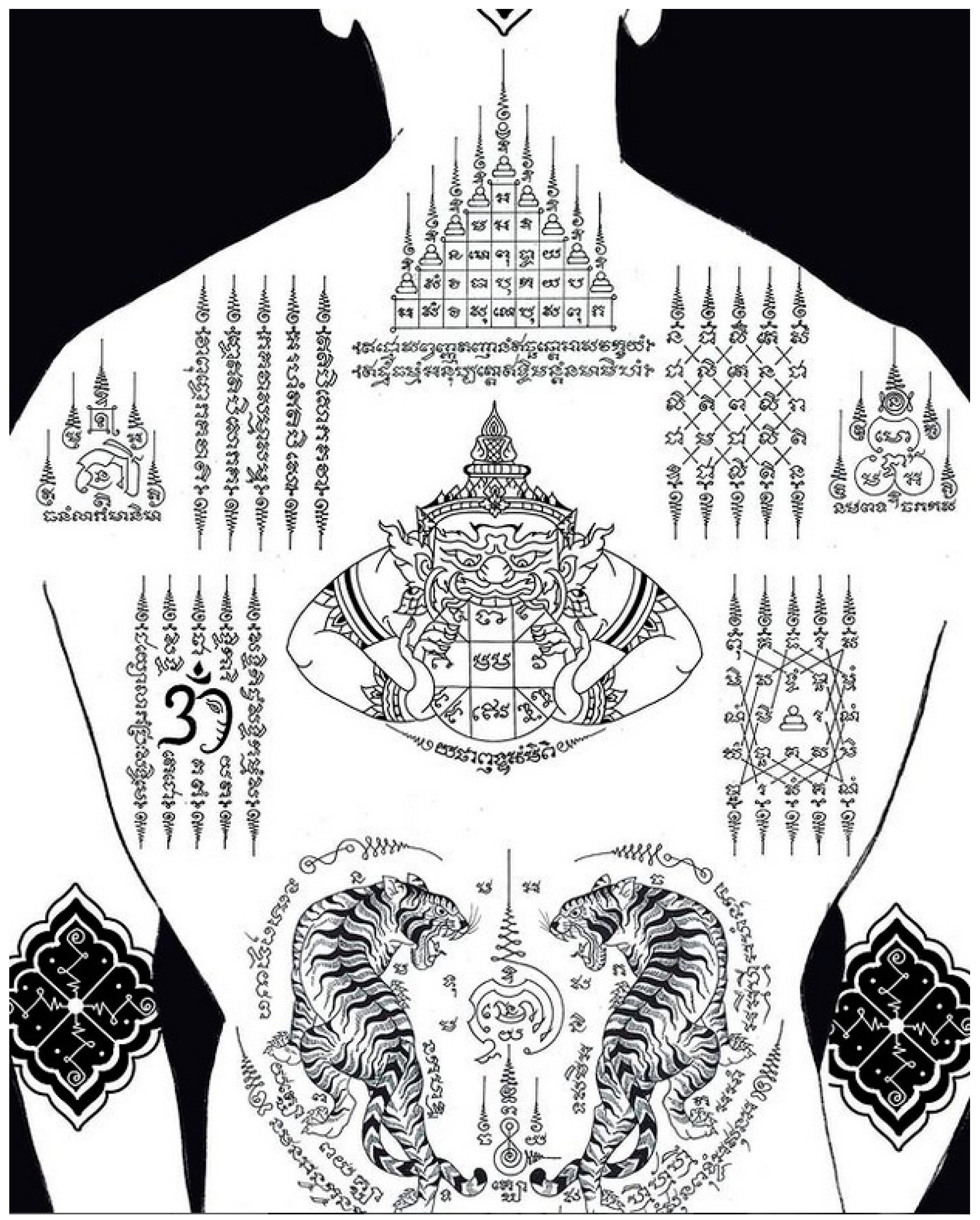

5. Sak Yant Design Elements

The term “Sak” refers to the piercing of the skin with a long needle, and “Yant” or “Yantra” to sacred geometry. Originally, the Sanskrit word “Yantra” means “a tool used for control” (

Chansanam et al. 2021, p. 1): “a yantra is understood to be an instrument designed to curb the psychic forces by concentrating them on a pattern, and in such a way that this pattern becomes reproduced by the visualising power of a person. But it is also regarded as a visual expression of a mantra” (

Igunma 2019, pp. 128–29). Besides Yantras in the narrower sense, Hindu gods are integrated in the designs, as well as text, and both the figural elements and abstract letters can form part of a geometric layout. “The script used for yantra designs varies according to culture and geography” (

Bangpra 2020, p. 1): usually it is Pali or Khmer, depending on the tattooing tradition (

Tannenbaum 1987, p. 695). Mul or “round” script is an example found on an ancient Buddha statue: “syllables condense or encapsulate specific verses or concepts used in Buddhist scholasticism and can be manipulated in multiple ways for worldly or soteriological ends. These letters, when connected together in short strings, form gāthās (คาถา, khatha) or mantras (มนต์, mon), namely incantations or magic formulae” (

Revire and Schnake 2023, p. 62). Letters can of course also be understood as visual shapes that trigger certain feelings or imaginations (

Skolos and Wedell 2006, p. 146, see

Figure 1).

Looking at their meaning, various classes of tattoos can be distinguished, such as those acting on others to make them like the bearer, the ones who increase the bearer’s skills, and those who protect the bearer (

Tannenbaum 1987, p. 696). In addition, Sak Yant designs are often considered to be more general talismans in Thailand (

Chansanam et al. 2021, p. 3), but, in modern times, Sak Yants have sometimes also “morphed into markers of mafia and gangsters, who use the tattoos’ protective blessings to perform acts of crime” (

Nieset 2018).

Although only few Sak Yant designs such as the Hah Taew, which is also worn by Angelina Jolie, are typically well known, there are many ways to design individual Sak Yants. It is “a common misconception that arjans/monk/hermit just choose based on reading your aura or energy. The idea is likely is due to some foreigners not having the ability to communicate with the ajarn, and so they would choose a yantra which holds a general protection spell for them, as they could not communicate on any deeper level” (arjannengthaisakyant 7 June 2023, sic). If possible, the customer explains his or her wishes and ideas, and then the master suggests a design. The term “master” here sometimes denotes a Buddhist monk, but especially among tattoo artists represented on Instagram, it most often refers to a person who knows or has studied the technique and the spiritual meaning. This is also reflected by the term “Arjan”, “Arjarn”, or “Ajahn”, which not only translates to “monk”, but also means “teacher” or “professor” and is derived from the Pali word “Acariya” (

Sharma and Sharma 1996, p. 35).

6. Evolving into Hybrid Signs

Sak Yant may be rooted in indigenous tribal animism, but it became increasingly tied to Hindu–Buddhist traditions (

Bangpra 2020, p. 1), where mystical geometric patterns are used as a tool in meditation. It is agreed upon that yantras were brought by Indian merchants and missionaries to Southeast Asia (

May 2014, p. 4) and were starting to be tattooed in the Khmer empire around the eighth century.

The tattoos were apparently first meant for men to show their bravery, and, contrary to today, often inked on legs (

Chansanam et al. 2021: 3). In times of war, they were supposed to serve as protection. Specific formulae that are still used today “have been known locally for centuries—at least since the late Sukhothai or early Ayutthaya periods” (

Revire and Schnake 2023, p. 72).

Today, the belief in its spiritual powers varies and in Thailand it may not be very strong among many of their wearers (

Chansanam et al. 2021, p. 3), who, e.g., also chose them for aesthetic reasons or to represent their cultural identity. Typically, Sak Yant designs are not only inked, but also sold, eventually to be tattooed by people who are not masters. An example of a master selling such a design is Ten (Teerayoot Boontem), who together with others runs the Instagram account unalomestudigbg. Further, Sak Yant designs are also used in jewellery and home décor.

Its history demonstrates that the art of Sak Yant has crossed religious borders and can itself be regarded as a hybrid sign (

May 2014, p. iii). Master Svietliy, who has learnt at a Buddhist temple in Thailand but works mainly in the US, places Sak Yant in the realm of individual systems of belief and practice, even though not everyone may agree on this, which actually adds to its hybridity: “Sak Yant is a non-religious practice. Similar to a personal Yoga practice, Yantra in a form of Sak Yant tattooing or even artwork, can help you improve in any religious or spiritual practice that you choose” (

Master Svietliy/Ajarn Sod Sai 2023). Master Svietliy runs a website on Sak Yants that can be seen in an educational or informative light but that has also the task of supporting his business.

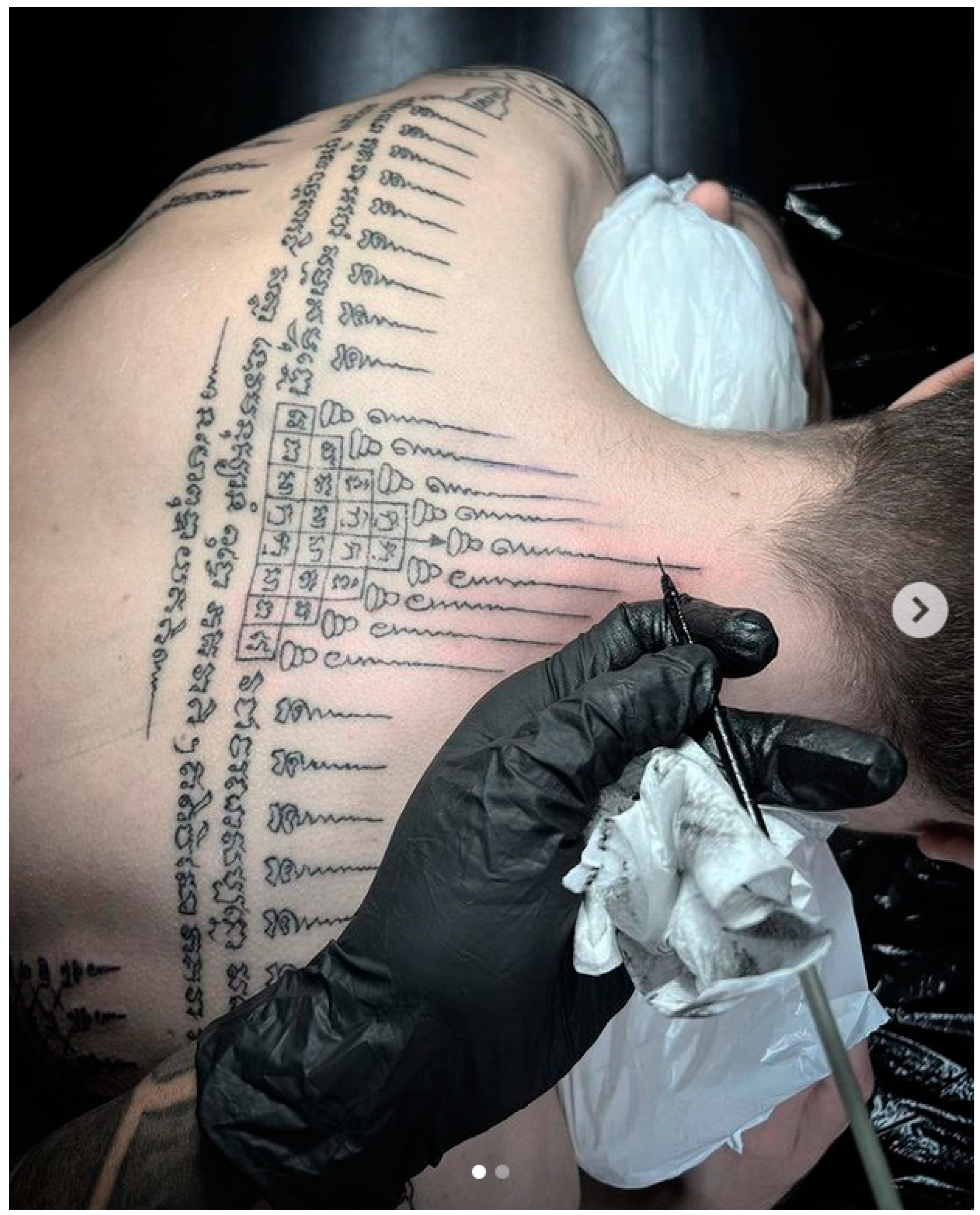

7. Rituals and Processes

The process of getting a Sak Yant can be described as a ritual that includes certain offerings, among them often fruits that represent nature’s blessings, cigarettes as a reference to hermits who had to ward off mosquitos, and alcohol that is used to sterilize the tattoo equipment. While tattooing with a the typical stick (see

Figure 2), the master “murmurs Buddhist chants to imbue the tattoo with special powers” (

Cook 2007, p. 26), and also, the person receiving the tattoo should say prayers, which will add to the powers of the tattoo. Immediately after the execution of the tattoo, a gold leaf will be placed on it, which „blesses the ceremonial process, the person, and the energy centers that are being worked with […] The gold leaf is temporary on the skin, but the blessings and prayers last lifetimes” (

Master Svietliy/Ajarn Sod Sai 2023).

Closing the ritual, a red string that should be worn for a certain number of days is often wrapped around the wrist of the tattooee. It should serve as a further reminder of the commitments entered into with the tattoo, rules that he or she should follow from now on. The time of wearing, sometimes set to 66 days, should allow the person to break old habits and become a new person, e.g., integrate meditation into one’s life and practise awareness and compassion. Here, Master Svietliy gives further explanation, which may actually be bad for his own business: “It is also recommended that you do not receive another tattoo during this 66 day period. These things can interfere with the healing process, weaken the powerful effects of your Yantra and make it far more challenging to establish and integrate the full expression and embodiment of your Sak Yant transformation and rebirth” (2023).

Once the tattoo is ready, its wearer must permanently follow a number of specific rules (

Vater 2011, p. 13), as frequently stressed in resources and on various websites, for example: “Do not swear on parents and teachers. Do not spit in the toilet. Man: Do not have sex with women while having their period. Women: Do not have sex while you are having your period. Do not suck, do not lick. Do not have sex with other’s husband/wife” (

Sak-Yant.net n.d.). These are the rules that were set up by Ajan Mueck and published online by a noncommercial platform that wants to educate about Sak Yants.

Whoever has received a Yant Grao Paetch (diamond armour) must not drink alcohol or use other addictive substances, otherwise it will lose its power, which cannot unfold again (

Sak Yant Foundation 2018). Thus, the tattoo forms an intricate relationship with the person and his or her beliefs and behaviour. Further, several tattoo artists and tattooees “believe that too many tattoos can interfere with a person’s personality and that some people simply don’t have the mental strength to handle certain tattoos” (

Bailey 2012, p. 29).

As mentioned, Sak Yants can use Hindu iconography but are most strongly connected to Buddhism and refer to its core techniques such as meditation: “While also used in countercultural and antimaterialist contexts, Buddhism in the West has truly entered the market as religion, spirituality, and provider of secular techniques in recent decades” (

Borup 2020, p. 227), and therefore, it can be seen as another area of conflict between appropriation and appreciation, understanding and misunderstanding or new interpreting, dissolving boundaries and exploiting otherness (

Borup 2020, p. 248).

8. The Method

This article is based on a sample that was collected on Instagram and is analysed with the help of a content analysis. Instagram is a social medium used to connect people, to communicate about oneself and/or to follow others, as well as to market oneself or one’s products and services. The immense importance of social media for information, education, communication, identity building, etc., has often been remarked on in scientific research (e.g.,

Dyer 2020, p. 28;

Roese 2018, p. 313f.;

Gündüz 2017, p. 89f.), as has their tendency to form filter bubbles created by algorithms that record which content a user prefers. Consequently, more similar content is played back to him or her, resulting in self-amplification (

Pariser 2011) and immersion in a topic—for better or for worse.

The sample was analysed in terms of how the Sak Yants are portrayed and marked in the posts, and to what extent there is an alignment with what the tattoo artists envision their (sub)target audience, the “Westerners”, to like and possibly want on their bodies. One has to consider that even though potential customers are the main target group, there may also be other target groups such as fellow artists, friends, etc.

9. The Sample

To achieve a representative sample, the first 10 Instagram accounts that appeared in July 2023 under the hashtag “#sakyant” and belonged to tattoo artists or studios were considered, and from these accounts, in turn, the last 10 posts in each case, i.e., 100 posts, of which some would date back several months, but none longer than this, were considered. Thus, the season during which most of the posts were generated was including both a typical European and North American holiday period but also dating back to early summer, when most people are not on holidays. This could have been relevant when looking at the profiles from artists from the countries of origin of Sak Yants; however, there was no noticeable difference between posts from early summer and high season.

As is typical for Instagram, all of the posts in the sample consist of one or more pictures—mostly photographs, but also graphics and/or videos. These pictures mostly show Sak Yants, either as ready tattoos or as tattoo concepts; furthermore, pictures of the process of tattooing could be found, as well as some pictures of the ritual, e.g., incense sticks held close to a fresh tattoo or gold foil put next to it. There were some pictures showing other tattoo styles, which indicates that the respective artists offer a wider portfolio of styles.

In all cases, text is accompanying the pictures, often several sentences that give information and several hashtags to help users find posts that are relevant for them, among them #sakyant.

Looking at both the texts and pictures, it became obvious that these accounts were at least partly aimed at an international audience, as illustrated by the use of English. Most accounts used not only English, but also Thai, Khmer, Swedish, Italian, German, or French, depending on their geographic focus. Further, those accounts that belonged to tattoo artists living in the countries of origin of Sak Yants sometimes emphasized the souvenir character. Besides the use of English, this also indicates that tourists are one of the target groups. Photographs and videos frequently showed Caucasian people getting tattooed. In addition, information about the tattooee was occasionally given, where he or she was from and what he or she desired.

In addition to the Instagram content analysis, I have interviewed five of the artists who were part of the sample and available and willing to answer some questions. This has been carried out in a semi-structured and rather informal way via Instagram. This should not be understood as a core method, but as a supplement, because social desirability may be a factor to be considered here such as presenting oneself as free from economic constraints. In this context, it certainly also plays a role that I cannot guarantee complete anonymity due to the Instagram sample.

10. The Social Actors

Given the data, it is not easy to make assumptions about social actors. The profiles in the sample are first and foremost dedicated to Sak Yants and often stress that the respective tattoo artists master this art, but as mentioned earlier, there are sometimes also images of other styles, and it is possible that the artists maintain other profiles as well. In some cases, I could trace back that the artists were part of tattoo studios that do not exclusively specialize in Sak Yant (e.g., unalomestudiogbg). This finding is interesting insofar as it can be deduced that, at least in some cases, there is no complete economic dependence on the Sak Yant style.

Whether the artists themselves post or, for example, the accounts are curated by studio owners or helpers, cannot be judged by looking at the postings, even if the texts are written in the first person. Yet, it can be assumed that the artists basically agree with what eventual social media managers post, as otherwise, tensions could arise.

The fact that some of the artists occasionally travel to different cities and countries to work as guest tattoo artists at other studios suggests that their profession makes for a comfortable life, which was affirmed by the interviewees; however, further information would be needed to make clear statements.

Mutual comments and likes between Sak Yant artists from all over the world lead to the conclusion that the artist community is well connected. Due to its (still) small international size, the filter bubble is still manageable, and it is easier to know each other. Further, other artists may be experienced less as competitors than as fellow campaigners for the common cause (

Jerrentrup 2021, p. 1136), which was confirmed by the artists I wrote with. Websites that educate about Sak Yant such as svietliy.com or the Sak Yant Foundation can also be seen in this context, which stresses the assumption that the artists’ common goal is not only making Sak Yants more popular, but also educating about the art.

Looking at the potential customers to whom the posts are primarily addressed, it is also difficult to socially locate them. Tattoos may be expensive, but they are one-time investments. If people get inked in the context of a long-distance trip, it remains unclear whether the tattooees travel often or rarely, low-budget or exclusive. It can perhaps be assumed that those who are specifically interested in Sak Yants have an overall interest in (foreign) culture(s).

In the literature on tattooing, it has been stated that “ironically, while some individuals invoke tattooing as a critique of consumer society, tattoos have themselves become a popular commodity” (

Kang and Jones 2007, p. 45). However, the semiotic registers of tattoos, considered as locally specific models of communication (

Agha 2007), can vary greatly in terms of the motifs themselves and the dispositifs (

Foucault 1980, p. 194f.) in which they are created: a typical prison tattoo has both a different look and a different genesis than a Sak Yant. Further, it has been noted that tattooed bodies are distinctively communicative bodies (

Wohlrab et al. 2007). In recent times, tattoos have not just been linked to (cultural) identity, but also individuality (

Adelowo and Babalola 2021, p. 139), and a study has shown that tattooed individuals “scored higher than the comparison group on need for uniqueness” (

Tiggemann and Golder 2006, p. 309), but generally do not invest more in their appearance.

11. The Representation of Sak Yant on Instagram

In the following, some peculiarities of the representation of Sak Yant within the Instagram sample will be discussed, both with regard to the pictures or videos shown and the accompanying text elements.

12. Sak Yant Explanations

Let us first look at the explanations that are usually given through texts: probably since the masters who are present on Instagram cannot be sure how much is known about Sak Yants among their potential clientele, under their photo or graphic posts, there are in more than 80% texts that explain the art of Sak Yant in general or specific Yants in more detail. In this context, it is often emphasized that both the way of tattooing and the motifs are traditional: “Traditional Sakyantthai tattoo blessing” (Sakyantthai_arjarnboo, 28 May 2023) appears under every post by Sakyantthai_arjarnboo.

The spiritual power of the Yant is also regularly stressed: “Yant Dok Bua (Lotus) – Super Charming, Wealth, Good for business and luck. The lotus flower represents one symbol of fortune in Buddhism, speak of spiritual awakening and mysticism. It grows in muddy water and this environment that gives forth the flower’s first and most literal meaning: rising and blooming above the murk to achieve enlightenment […]” (spiritualsakyant 5 June 2023) or “This yant is known as yant Spirit, which means protection from evil spirits as well as strength, power, energy and successful. From studio to be blessed with our master of this Sakyant art” (Bamboo_sakyant 1 May 2023). The last quote shows that the spiritual power of the design that is created and/or implemented by the master is uniquely intertwined with the master’s spiritual power.

Individualization is also occasionally addressed, ie., that Sak Yants can be adapted to personal needs and consequently are not 1:1 copies, which meets the special need for uniqueness (

Tiggemann and Golder 2006, p. 309) among tattooees.

The in this context very important aspect of the ritual is also emphasized in about one quarter of the posts: Preservation_khmer_sakyant, for example, mentions in every post the offerings that must be brought if one wants to receive a tattoo. In many accounts, one can also occasionally see photos of the ritual, for example people with incense sticks, the tattoo with gold foil, etc. When videos are posted, they also frequently show the ritual, which also offers a unique selling proposition of traditional Sak Yant compared with other tattoo styles.

Further, cultural openness is sometimes mentioned in connection with Sak Yant: “I hope you love my work. Welcome everyone” (Sakyantthai_arjarnboo, 28 May 2023). This does not necessarily mean that the Sak Yant itself stands for openness, but the master associated with the art does, as does the “Western” wearer, who decided to immortalize something from another cultural context on his or her body. Another example is bamboo_sakyant, who posts “[…] If you’re passing through Siem Reap, stop in and check out our artists. Come to feel the culture, the spirituality, and the professional work of Bamboo […]” (4 June 2023).

In the interviews, these aspects were confirmed, and it was stressed that the artists see themselves as educators as well, both in the field of knowledge and of spirituality.

13. Foki in Marketing

The above explanations about Sak Yant are of course related to the marketing of the art, which sets several foci:

As stressed by all the Instagram accounts—not under every post, but still often—and also by the interviewees, there is a belief in the powers of the tattoo, in the protection, healing, and luck that the Sak Yant could offer. Thus, the body is presented “as a spiritual canvas” (

Sudbury 2015, p. 165), offering support for the wearer that goes beyond the visual. The connection to healing also exists with other tattoo styles, for example, as already found with Ötzi (

Piombino-Mascali and Krutak 2020).

In addition, Sak Yants are marketed by artists from Thailand as a souvenir of a trip: “Travel is made up of little moments that change you forever. From the food you eat to the people you meet, travel changes us all in one way or another. Sak Yant is one of those experiences that touches the soul and never let go” (Arjannengthaisakyant, 11 May 2023). This journey can therefore be understood as a kind of educational journey, as a combination of an inner and outer journey or as a rite of passage that includes a transformation: the person receives a new status through the ritual and the resulting tattoo. This status includes a permanent indexical relationship with the master, which is also related to protection. However, it could also be argued that something invasive, such as a tattoo, is needed to make a trip memorable in the face of countless experiences that people, especially privileged “Westerners”, can easily obtain nowadays. Consequently, a Sak Yant may be detached from its actual meaning and be just a very drastic way to make something memorable. Yet, there are many other choices for extraordinary experiences and other tattoo styles to choose from, so this argument falls a bit short.

As mentioned, the aspect of cultural openness is also stressed. Openness is communicated by the body with the foreign tattoo, and at the same time, the wearer establishes a community with people from other cultural contexts, illustrated by posts such as the question “Want to be part of it?” (nessa.leyrer 24 February 2023) or the personal relationship articulated in “Thank you so much brother from France […] He just came to Siem Reap for the tattoo, very respect that brother!” (preservation_khmer_sakyant, 30 May 2023). Here, not only a relationship to the culture of origin is established, but also to people from all over the world wearing Sak Yants. Further, as can be seen in many pictures on Instagram, “Western” customers who get a Sak Yant often already have tattoos from different contexts, so that their bodies turn into multicultural, multisignifying canvases.

The specific motivations from both the tattoo artists and the tattooees, however, should not be imagined as homogeneous, as their various “economic, cultural and social life[s] are deeply imbricated” (

Redden 2016, p. 231).

14. Evaluation

In the following, I will be concerned with examining, on the basis of the previous aspects, whether the worldwide marketing of Sak Yant Tattoos should be understood as cultural appropriation, taking into account the aspects of nonrecognition, misrecognition, and exploitation (

Lalonde 2019, p. 329), and where the special appeal that this art apparently possesses may come from. These questions cannot be clearly separated but go hand in hand.

I have to mention that my insights into the topic are so far limited, as I cannot take into account Sak Yant artists who do not use Instagram, be it that they do not have the time to do so, that they do not see any benefit, consider the medium to be harmful for the art, or for other reasons. There may also be accounts that actually tattoo in the style of Sak Yant, but do not use the respective hashtags. In the interviews, I have also heard of some tattoo artists who only copy the style, but do not use the term. However, this seems to be a rare phenomenon, perhaps out of respect for the traditional art, or perhaps because the (informed) customers want the original anyway.

15. Benefitting from the Art

Looking at the sample, it is clear that at least among the (future) clientele, the art of Sak Yant is recognized to the point that people want to have this immortalized on their own bodies by Sak Yant masters. The profiles analysed and the participants in the interviews all belong to traditionally trained masters, most of them apparently with roots from the respective countries of origin. Obviously, the relationship with the master can play a more important role than in other styles, where tattoo artists are sometimes celebrated, but can also be regarded primarily as a service provider. Here, on the other hand, the masters benefit from the fact that the spiritual dimension can only be guaranteed by someone not only trained in tattooing, but someone who also stands for spiritual abilities. Thus, one can at least state that, in general, people from the countries concerned—whether residents or emigrants—profit from the global popularity, as does the respective tourism industry. An adaptation and change of style, possibly also a stronger adaptation to so-called Western aesthetic ideas, is currently (still) relatively rare, although some accounts like neobuddhism.bohemian (not part of the sample, as they do not use #sakyant) tend in this direction. For a short while now, “#mindfultattooing”, a hashtag that is quickly gaining popularity, is part of a trend that also points in this direction.

Nevertheless, some adaptation to the (perceived) wishes of “Westerners” could also take place in Sak Yant. This does not affect the traditional motifs, which, as is increasingly emphasized by the accounts and confirmed by the interviewees, can also be adapted to the respective customer and their eventual wish for individuality: “Please be aware some of the design might look the same but we are customized the meaning based of people’s personality and requests” (arjannengthaisakyant I July 2023). The placements, almost all in the area of the arms and back, also correspond to the traditional placement. However, it is noticeable that the rules to which one must adhere in order to maintain the power of the tattoo are almost never communicated on Instagram. Whether these are then set out at the tattoo appointment itself, and if so, how strongly specified, is of course not clear by looking at an Instagram sample. In the interviews, they mostly mentioned “living righteously”; one interviewee emphasized that his rules, which were not communicated to me further, were easy to follow and important in life anyway. Another person emphasized that drugs must be avoided.

Apparently, some shift in meaning may also play a role: this could be seen in the fact that the descriptive texts often do not address the exact translation or the meaning of very specific Sak Yants but remain rather general. This shift in meaning corresponds to some newer interpretations in the countries of origin (

Chansanam et al. 2021, p. 3). The artists interviewed also stressed that Sak Yants have a general talismanic character. One explained that Sak Yants generally reflect human needs and that these can be condensed into different designs.

Overall, one could say that the benefits are well distributed among real practitioners and not freeloaders who only copy the style, and that the meanings and practices are not distorted.

16. Aesthetics versus Spirituality

As illustrated, the appropriation of Sak Yants could be particularly explosive, since not only visual features, but also spiritual beliefs that belong to a nonprivileged, “Eastern” culture, play a role. Thus, misrecognition may be an issue.

However, this already resonates with an evaluation that could well be questioned: even in the case that a Sak Yant is seen primarily as an aesthetic asset in the “West”, the question arises as to why aesthetics should represent a category that is subordinate to spirituality. Even in classical “Western” philosophy, for example, aesthetics represents an important field. Deriving from the ancient Greek “aisthesis = perception/sensation”, aesthetics means the doctrine of the sensually appearing or of perception in general or, as a philosophical discipline, the doctrine of the beautiful and its experience. Here, too, it is already apparent that aesthetics is not a completely separate, subordinate field—all the more so, however, if one leaves behind a Eurocentric view of aesthetics. Looking at other cultural contexts, it becomes apparent that aesthetics can be embedded differently: in classical South Asian philosophy, for example, the aesthetic experience is regarded as the experience of certain emotions and, beyond them, as an opportunity for a feeling of transcendental unity with the work, artist, and recipient. Accordingly, the categorization “(valuable) spiritual here, (superficial) aesthetic there” seems untenable. Wanting a Sak Yant for aesthetic reasons, consequently, may not necessarily be inferior to getting it for spiritual reasons.

Further, the analysis of the Instagram accounts does not reveal the extent to which potential customers desire the Sak Yant for its aesthetic qualities or as an interesting experience, or for other reasons. However, this does not only concern people from a foreign cultural context: “These days, Sak Yan for beauty or charm has also begun to play a role” (2021: 3) writes Chansanam with regard to Thai people. Ethnicity and the degree of belief are obviously not tightly connected. The marketing has further shown that the spiritual aspect does play a role also for “Western” customers, as does the aesthetical. The interviewees have affirmed that both aesthetics and spirituality are important to their clients.

17. Body and Mind

The stress in the marketing of the Sak Yant on the physical, as well as the spiritual dimension, on body and mind, can be seen in context with Buddhist practices, which revolve around the self and the body (

Cook 2007, p. 22). As outlined by

Sprenger et al. (

2022, p. 2), in “Western” philosophy, a central concept is the distinction between nature and culture, whereby man is on the side of culture due to his likeness to God and his ability to reason, even if his body points to the side of nature. This sets the spiritual mind apart from the natural body. However, both do not have to be seen as separate entities (and in many cultural contexts are not understood as such, see

Descola 2013, p. 4ff.), and it can be argued that even in “Western history”, this has not been so clear-cut, as demonstrated by movements such as Romanticism (

Mathieu 2022, p. 549), which turned against the dualism and saw and an “embodiment of mind” (

Richardson 2005, p. 1). In Buddhism, the relation of nature and culture, body and mind, is neither viewed as “dualistic in a Cartesian sense, nor monistic. Rather, it represents a genuine alternative to these positions by presenting mind/body interaction as a dynamic process that is situated within the context of the individual’s relationships with others and the environment” (

Ozawa-de Silva and Ozawa-de Silva 2011, p. 95).

This relation of body and mind already plays a role in the ritual of getting a tattoo: the pain one experiences can reflect the Buddhist perspective on suffering, which is a core of Buddhist teaching. Confronted with suffering, the king’s son Siddhartha Gautama left his privileged life and practiced physical and spiritual discipline to find out the reason for this very condition (

Chen 2006, p. 74). “Dukkha” is often comprehensively translated as suffering and is considered the first “noble truth” and a characteristic of human life. Dukkha “is eventually stressful because there is a difference between the unified reality and humans’ conception of reality” (

Tyson and Pongruengphant 2007, p. 353). Suffering physical experiences can be alleviated through the acceptance and recognition that they are part of life. Thus, the pain of being tattooed can be seen as a reflection on this general human experience, and the purpose of the tattoo as “a tool intended to help focus the mind” (

Vater 2011, p. 11) begins with the acceptance and overcoming of this very pain.

Further, tattooing includes “the transformation of pain into beauty” (

Buss and Hodges 2017, p. 4), conceivable as a metaphorical process. The notion of a “purposeful and productive pain”, which has been used when referring to labour (

Whitburn et al. 2019), may apply here as well: suffering leads to a result that in the eyes of the client is desirable, loaded with meaning, and in most cases, indelible (even though the notion of permanence has been contested, see

Kloß 2020) and forever embedded in a ritual that may have caused a significant change to the person. Therefore, one interviewee said that it was also important to endure the pain, and that he did not think much of numbing creams. The pain itself is contextualized in the ritual in a special way: it forms a part of the ritual, and accordingly, the endurance also belongs to it. In this contextualization, mindfulness-based pain therapy comes to mind: this technique can play a role in changing and thus controlling the experience of pain (

Tamme and Tamme 2010, p. 9). Psychotherapy has also considered the relief, release, and calming of pain, as physical pain can help block out stresses (

Scarry 1992). However, this specifically refers to self-injury (

Fliege 2002, p. 195), which clients try to overcome with the help of therapy. There are also case reports of individuals who use tattooing and its associated physical pain to regulate affective states (

Anderson and Sansone 2003, p. 316). However, an “addiction” to tattooing may be prevented in the case of Sak Yant by rules such as one should not get another tattoo soon after a Sak Yant.

As a result of this ritual, there is not only the memory of the ritual (

McCauley 2001, p. 115), but also the permanent indexical and thus embodied relationship to the master (for rituals and indexicality, see

Rappaport 1974, p. 13; for transmission and reinforcement of social norms,

Rossano 2012, p. 529). In principle, indexicality exists in any tattoo, but in this case, it is all the more important, because the master is more than just a service-providing artist, as illustrated above.

18. Conclusions

As this analysis has shown, Sak Yant involves a special way of bringing aesthetics and spirituality, body and mind, together. This may be common to other tattoo styles, for example, when a tattoo is intended as a reminder. However, the explicit ritual in which the Sak Yant is embedded makes it all the more apparent in the Sak Yant. Through the ritual, both spirituality and aesthetics and body and mind are, in a sense, united. Perhaps this is what makes Sak Yants so popular among so-called “Westerners” and satisfies their very needs: the integration of aspects that are often seen as the opposites. This hypothesis should, however, be tested by further studies.

It is difficult to locate Sak Yant tattoos between the poles of cultural appropriation and appreciation. However, at least the accounts in the sample seem to revolve around people who have had special training that includes the value system around the Sak Yant, and usually either come from relevant areas or have been trained there, which may prevent exploitation (

Lalonde 2019, p. 330). For the tattoo artists, it may be an income-generating activity, but as quite a few also offer different styles, it is (partly) their choice to offer Sak Yant. Free-riding—a tattooist without any connection to the style copying it—is certainly curbed by education, but still cannot be ruled out. Further, the analysis cannot give information about power dynamics in tattoo studios or in the areas in which the Sak Yant originates. Both would require participant observation, for example.

Through their Instagram posts, but also with related websites, Sak Yant masters offer background information on the topic to prevent nonrecognition or misrecognition. If one assumes that marketing is also oriented towards the (anticipated) customer wishes, cultural knowledge and understanding are apparently important on the side of these very customers, and thus, recognition matters. Certain changes, for example to make it easier for clients to follow the rules, may play a role, but ultimately, it is about higher goals: about the (aesthetic) integration of spirituality into life, about hope for various life goals, perhaps also about the reminder to behave righteously, and the integration of both the otherworldly and one’s own, physical manifestation. Again, however, one could test whether the change or different interpretation of the rules to be followed is merely in keeping with the spirit of the times or represents an actual violation. Participant observation and in-depth interviews would be useful methods for this.

Thus, we can conclude that Sak Yant tattoos offer a distinctive feature that sets it apart from other tattoo styles. Instead of cultural appropriation or appreciation, it is perhaps more appropriate to speak of cultural participation or integration.