1. Introduction

Randall Collins introduces the concept of interaction ritual chains in his exposition of interaction ritual theory, thereby illuminating the intricate manner in which interlinked rituals of everyday life exert influence over the social life.

Collins’ (

2004) formulation of the interaction ritual chains theory stands as a salient and contemporary sociological theory, commanding substantial acclaim within scholarly circles. Scholars from various fields have used the theory to investigate topics ranging from education (

Wilmes and Siry 2018) and tourism (

Sterchele 2020) to criminal justice (

Rossner 2011) and violence (

Jensen and Vitus 2020). Despite its widespread use, it is noteworthy that the theory has received limited elaboration in terms of theoretical development.

One of the most innovative aspects of Collins’ theory is the concept of emotional energy (EE), which can be described as the fuel for the development of group solidarity in human communication (

Collins 1981). However, there is still an opportunity for further theoretical and methodological advancements to enhance our understanding of the process by which common sentiments are cultivated among actors during an interaction ritual. In this article, I propose the concept of emotional ambience (EA) as an addition to Collins’ interaction theory, to focus on the collective emotional process in an interaction situation. The aim, therefore, is to elaborate on Collins’ interaction ritual theory by proposing the concept of emotional ambience as a complement to emotional energy.

To aid in the analysis of emotional ambience, I propose a three-dimensional model that outlines the valence of collective emotions (ranging from pleasant to unpleasant), their level of arousal (from low to high), and their strength (from low to high). Methodologically, the focus lies in the emotional coordination of gestures, facial expressions, intonation, volume, and speech rhythm within interactions.

Collins’ theory delineate how collective actions and shared cognitive and affective orientations within a group can transform into feelings of unity and reverence towards the group’s symbols (

Collins 2004). When interaction rituals succeed, they generate emotional energy (EE) characterized by heightened levels of self-assurance, enthusiasm, and initiative. Conversely, unsuccessful interaction rituals diminish EE. This leads individuals to be motivated to replicate interactions that generate heightened EE and avoid those that deplete it.

The concept of emotional energy is often misunderstood, with some equating it with Durkheim’s notion of collective effervescence, and thus using it to refer to the collective emotional state in a given situation (see below). In fact, emotional energy refers to the long-term impact of interaction rituals on individuals, persisting beyond the immediate interactional context. An appropriate term for emotions that are socially created and diffused would, as a suggestion, be emotional ambience, which is situational and arises between people. Emotional ambience provides the foundation for the emotional energy that individuals may experience. Notably, there is a reciprocal relationship between emotional energy and emotional ambience, as the emotional energy that individuals bring into an interactional situation can influence the emotional ambience.

The separation of EE and EA is crucial for understanding that even mutual sharing of unpleasant emotions, for example sorrow and sadness, can charge individuals with emotional energy and strengthen social bonds.

2. Interaction Ritual Theory

To commence, let us analyze the pertinent elements of Interaction Ritual Theory (IRT). IRT draws on Durkheim’s sociological investigations of religion, published in

The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (

Durkheim and Swain [1915] 2008). In his examination of the Australian Aborigines, Durkheim identified the fundamental underpinnings of the social significance and function of religion. Participation in religious rituals involves the affirmation of shared symbols and the endorsement of communal codes of conduct, thereby serving an integrative purpose for the community. For instance, a funeral can be viewed as a ritual, not for the deceased, but for the survivors who must reunite the group that the deceased has recently departed from, and consequently altered the group dynamics (ibid.).

Durkheim emphasizes the importance of the social assemblage in religious rituals (

Durkheim and Swain [1915] 2008). The physical congregation of human beings is a fundamental prerequisite for a collective experience, interpersonal attunement, and the formation and intensification of a common emotional state, which Durkheim refers to as collective effervescence (ibid.). This can be regarded as a heightened state of intersubjectivity (

Collins 2004). Two main factors contribute to this state. The first is the performance of actions that contribute to the collective ritual, and linked to this is a mutual consciousness. It is through the repetition of the same chorus in the same rhythm and tone, and the same gestures in relation to a shared object, that people experience a sense of unity. The second factor is the shared emotions; emotional expressions that harmonize with each other, forming the basis for intensification and mutual exaltation—i.e., collective effervescence (ibid.).

Besides Durkheim, Goffman played a vital role in the advancement of interaction ritual theory. Goffman’s contributions can be identified in two key areas. Firstly, he introduced the notion of ritual in a pronounced micro-sociological interactionist framework. Secondly, he shifted attention towards non-religious, commonplace scenarios of daily life.

Such ceremonial activity is perhaps seen most clearly in the little salutations, compliments, and apologies which punctuate social intercourse, and may be referred to as “status rituals” or “interpersonal rituals”. I use the term ‘ritual’ because this activity, however informal and secular, represents a way in which the individual must guard and design the symbolic implications of his acts while in the immediate presence of an object that has a special value for him

Goffman’s words bear the echoes of Durkheim, i.e., rituals are prescriptions for how individuals should behave in the presence of sacred objects, but in Goffman’s version, the rites around sacred objects are translated into guidelines for actions around socially valued phenomena in everyday life situations, more specifically the meaning of the established orders that surrounds the rituals of everyday life.

The inquiry into distinctions between a religious and a non-religious conception of ritual constitutes a comprehensive and multifaceted discourse. The exploration of rituals, alongside the explication of the ritual concept (e.g., its definitions), has persisted since the 19th century, captivating the attention of sociologists, anthropologists, historians of religion, sociobiologists, philosophers, and historians of ideas (

Bell 1992). Notably, Durkheim engaged primarily with religious rituals from a sociological (functionalist) perspective, emphasizing the social purposes inherent in these rituals—fostering communal bonds and preserving group cohesion. Consequently, within this framework, he diminishes the significance of distinguishing between religious and secular rituals. When the focus is on the social implications of the ritual, the symbolic content—whether religious or secular—takes on secondary importance. Goffman expanded upon this sociological facet, assimilating it into an interactionist framework, thereby diverging from the functionalist paradigm.

Goffman is interested in greeting practices, courtesies, facial expressions, and gesture procedures in the presentation of the self as interaction rituals with symbolic and micro-functional significances. It is stereotypical interactions, such as these conventions, that form the fabric of social life in society. But the meanings of the interaction rituals are most clearly visible when the focus is directed towards what happens when the social rules surrounding these are violated. According to

Collins (

2004),

Goffman (

[1961] 1990) argues in

Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates that patients in mental hospitals are considered mentally deficient merely because they repeatedly violate the social regulations on which interaction rituals are based. It can be comprehended that Goffman posits the notion that interaction rituals serve as the foundation for the moral order in society. Furthermore, one may observe the influence of Durkheimian functionalism in Goffman’s perspective, as Durkheim contended that the moral sentiments of a tribe stemmed from their religious rites (

Durkheim and Swain [1915] 2008, p. 207f). The individuals who participate in and generate collective effervescence are strengthened by a shared sense of acting in accordance with moral principles.

One of the leading theorists in the framework of IRT is Collins. To gain an understanding of Collins’ theoretical perspective, it is useful to know that he takes his starting point from the fundamental question of sociology as identified by Durkheim, which is what holds society together (

Durkheim 1997;

Collins 2004)? Durkheim’s answer to this question is the mechanism that produces moral solidarity, and Collins emphasizes that moral solidarity, the binding force that holds society together, is created through interaction rituals (

Collins 2004).

Collins makes a bold assertion that his theory, interaction ritual chains (IRC) can account for social phenomena at any level. Social structures, even at the meso and macro levels, are ultimately based on repetitive actions in micro social situations, according to Collins (

Collins 1981). As a result, rituals emerge as the fundamental framework for comprehending social actions, as they form the building blocks of social life. Thus, Collins employs IRC to explain a wide range of social phenomena, including smoking as a historical phenomenon, social stratification, sexual intercourse, and even philosophies and cognitive processes (

Collins 1998,

2004). In Collins’ framework, interaction rituals play a crucial role, as individuals draw emotional energy from these rituals and use it as fuel for subsequent interactions, resulting in the formation of interaction ritual chains.

As per the IRT framework, the exchange of cultural capital is what constitutes the content of an interaction (

Collins 2004). The efficiency of cultural capital exchange between the participants in an interactional context determines the extent of group solidarity that is formed (ibid.).

A group of individuals (at least two) in physical presence—bodily copresence—so that they can perceive each other’s micro-signals; body language, facial expressions and tone of voice.

A common focus—intellectually, emotionally, visually, auditorily, etc. Through individuals directing their attention to the same object and being mutually aware of this, intersubjectivity is established.

An intersubjective feeling or a manifested collective mood that participants both create and adapt to. The collective focus and emotional manifestations are reciprocally regulated so that a stronger common focus creates a greater coherence of moods among the group participants and vice versa.

A boundary against outsiders to define who is included and who is not included in the group.

In recurring, lasting, and successful interaction rituals involving the same participants, symbols tend to be established that represent community within the group, i.e., sacred objects in Durkheim’s sense. Well-functioning interaction rituals also give rise to emotional energy and trust between the individuals who participate in the group’s rituals and respect its symbols. Vice versa, indignation and anger towards those who do not respect the rites and symbols of the group may arise (

Brante 2004, p. 107).

Emotional energy (EE) is the dynamic force that results from social situations when the group dynamics with regard to the aspects above work well, and enthusiasm and feelings of solidarity are generated and mutually incorporated by the participants. When interaction rituals are successful, they strengthen group cohesion and generate EE among participants. Conversely, failed interaction rituals result in drained emotional energy. The presence of EE is associated with increased action power, confidence, enthusiasm, and elation, while a lack of EE is linked to feelings of boredom, powerlessness, and depression. Collins posits that individuals act as EE maximizers, implying that people are driven to actively seek social environments anticipated to generate EE, while concurrently evading contexts that might diminish it.

3. Emotional Energy as an Inner and Individual Phenomenon

Emotional energy and the emotions expressed during an interaction ritual are not interchangeable terms. Collins provides a succinct explanation for distinguishing between these two concepts.

The outcome of a successful buildup of emotional coordination within an interaction ritual is to produce feelings of solidarity. The emotions that are ingredients of the IR are transient; the outcome, however, is a long-term emotion, the feelings of attachment to the group that was assembled at that time. […] I refer to these long-term outcomes as “emotional energy” (EE).

Emotional energy is not merely the individually or collectively manifested emotions in an interaction ritual. Instead, it is the retention of the interaction ritual that constitutes emotional energy. Emotional energy refers to the strength or lack of strength that individuals carry with them as a result of the interaction. It extends beyond the immediate situation in which it arises. In other words, emotional energy is not the emotional atmosphere or mood of a given situation, but the lasting effect of the interaction ritual on the individual.

In research using Collins’ IRT, the concept of EE is, however, recurrently misunderstood. For example, Milne and Otieno, who inquire into high school students’ engagement in group work during chemistry lessons, write in their description of their theoretical approach

We prefer the term positive emotional energy because it captures the sense that this energy is available to all participants. It does not reside in individuals but in the successful interactions that occur in classrooms

Milne and Otieno argue that EE is a collective rather than an individual phenomenon. Their assertion that “It does not reside in individuals […] (ibid.)” contradicts Collins’ claim that, “IRs generate a variable level of emotional energy (EE) in each individual over time […]” (

Collins 1993). Although Milne and Otieno’s investigation of the positive energy that they aim to capture is intriguing, it is not in the same sense as Collins’ long-term outcome of an interaction ritual, referred to as EE. Other researchers have also misused the EE concept to describe the collective mood of a situation (for example

Bellocchi 2017;

Davis et al. 2020;

Ritchie et al. 2013;

Wilmes and Siry 2018;

Feyzi Behnagh 2020;

Appanna 2022). It is essential to emphasize that the aforementioned studies hold great importance and contribute positively to the field. Investigating collective emotional states and processes is indeed valuable. However, the term EE is not suitable for describing such phenomena.

To distinguish EE from collective emotional states and processes, Collins employs terms such as “buildup of emotional coordination”, “social atmosphere”, “shared emotion”, and “emotional entrainment”. However, Collins lacks a theoretical or methodological model to effectively capture these collective situational emotions. Apart from these aforementioned formulations, Collins also draws on Durkheim’s concept of collective effervescence, which is rather limited. Durkheim uses collective effervescence as a label for a specific state, namely the excited state that participants in a religious ritual may experience. For instance, the term effervescence is not an apt description of the ambiance during a yin yoga group session.

This suggests the necessity for a more elaborated concept for inquiring about collective emotions in social situations.

4. Emotional Ambience

In this regard, I suggest emotional ambience (EA) as a concept for designating collective emotions characterizing an interaction ritual situation. While the concepts of “emotional atmosphere” and “emotional climate” may initially seem appropriate, these terms are somewhat metaphorical, as they refer to the gases surrounding the earth and meteorological conditions, respectively. Additionally, these terms have been used by other researchers to describe different phenomena (

De Rivera 1992;

Conejero and Etxebarria 2007). For reasons discussed below, neither is the term group emotion suitable to depict the emotional ambience.

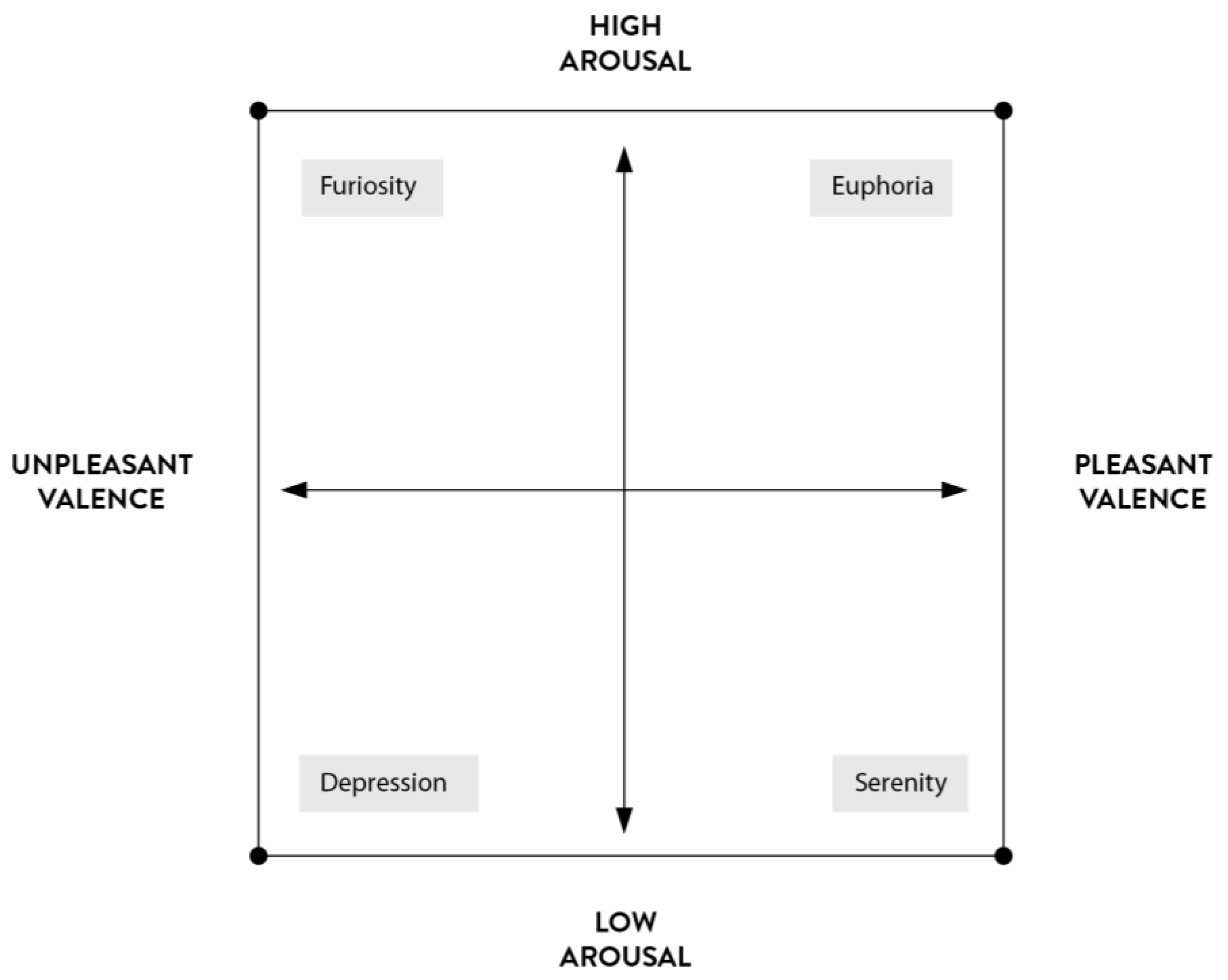

The language used to describe emotions indicate variations in levels of arousal and valence. Linguistic representations of emotions imply aspects of what people normally value as pleasant and unpleasant. For instance, words like euphoria and serenity denote emotions of pleasant valence, while furiosity and depression refer to emotions on the unpleasant side of the valence spectrum. However, these words also convey different degrees of arousal, with serenity and depression indicating low levels of arousal and euphoria and furiosity indicating high levels. The two-dimensional space between the axes of pleasant—unpleasant valence and high—low arousal, thus appears to provide a suitable means to explicate emotions (

Figure 1) (

Yik 1999).

In the field of psychology, several models have been established to conceptualize emotions, which relate them to two or three dimensions with some variations (

Russell 1980;

Watson and Tellegen 1985;

Larsen and Diener 1992;

Thayer 1996;

Yik 1999). The dimensional models portray emotions as being variable on a continuum of specific aspects, such as arousal and pleasantness. Consequently, they reject the notion that emotions are distinctly separate from one another and the idea that emotions have different neurophysiological foundations. In contrast, discrete emotion theory posits that a limited number of core emotions are biologically distinct from one another, and the expression and recognition of these emotions are fundamentally the same for all individuals, regardless of ethnic or cultural differences.

One of the most well-known dimensional models is Russell’s circumplex model, which suggests that emotions are distributed in a two-dimensional space containing arousal and valence dimensions (

Figure 2) (

Russell 1980;

Yik 1999).

In terms of their structure, the EA model and the circumplex model of affect appear to be similar, but they differ in two fundamental respects. Whereas psychological models pertain to individual and “inner” emotions, the emotional ambience model pertains to collective situational emotions. These emotions are formed and coordinated among individuals within an interactional context.

In accordance with the perspective of sociologist

Asplund (

1987), I place emphasis on emotions as social phenomena. Asplund posits that emotions are not merely derived from internal processes, but rather are formed and employed through social practices. Therefore, emotions are a product of external influences rather than solely internal ones.

Perhaps more widely recognized is

Hochschild’s (

1979) interactionist model of emotions, which pays regard to the

function of emotions in social interactions. However, it is worth noting that a functionalist model may have its limitations. It is also important to consider the potential dysfunction of emotions in interaction situations. Dysfunction refers to emotional practices that do not contribute to the enhancement of social bonds but are dysfunctional for group solidarity.

The emotional ambience does not simply emanate from individual emotions but rather stems from the situation at hand. The phenomenon can be likened to that of an ensemble of musicians who, through synchronized and attuned playing, collectively elicit a particular mood in a song. Furthermore, the song tends to elicit an affective response through a self-reinforcing feedback loop, whereby the musicians become affected by the mood of the song, which in turn is expressed through their instruments. Durkheim and Collins support this argument. Durkheim employs the notion of “social contagion” to describe the diffusion of affective states among a gathering of individuals via communal rituals, thereby giving rise to a particular emotional tenor during religious ceremonies (

Durkheim and Swain [1915] 2008). Collins utilizes the terms “emotional build-up,” “emotional entrainment,” and “emotional coordination” to describe collective emotional processes during non-religious interaction rituals (

Collins 2004). Therefore, the question at hand is whether the actors’ actions and emotional expressions become more coherent during interaction rituals (for further details, see the methodology section).

One might expect the concept of group emotion, which is well-established within social psychology, to be appropriate in this context. However, I have opted for the term emotional ambiance because group emotion pertains to the issue of emotions as individual phenomena. According to Barsade and Gibson, group emotion is a collective affective state of a group or team that can be measured as the mean, variance, minimum or maximum, and homogeneity or heterogeneity of individual members’ acute emotions, longer term moods, or dispositional affect (

Barsade and Gibson 1998). In essence, group emotion refers to the summation of individual internal feelings within a group, which also encompasses long-term moods. In contrast, the emotional ambiance exists solely in the situation and is more interactional, considering emotions as social phenomena.

The second key difference between the psychological models and the model of EA is that while the former purport to accurately represent reality as it pertains to human emotions, they do so within the confines of a positivist tradition founded on scientific realism. In contrast, the EA model is not intended to be a mere representation of a particular facet of the world; rather, it functions as a tool for studying and analyzing the world, drawing upon a critical realist foundation. Critical realism, as an epistemological approach, maintains that theories are not perfect reflections of reality, capable of fully explaining or describing phenomena. However, theories are not entirely divorced from the reality they seek to elucidate; there is a measure of correspondence between a theory and certain properties of the phenomenon it aims to describe. The depiction of emotions is inevitably a simplification of the complexity that empirical reality entails. Consequently, the EA model is not intended to be a definitive script for reality, which asserts that a specific emotion has a definite degree of arousal and pleasant-unpleasant valence. It is worth noting that joy can encompass, to some extent, varying degrees of arousal and pleasantness, and there exist no clear-cut boundaries between joy, satisfaction, and elation. From a critical realist perspective, theories, concepts, and models are imperfect, but fruitful means for understanding the world. Accordingly, the EA model serves as a tool to trace the dynamic changes in the emotional ambiance, including the fluctuations in arousal and valence, during an interaction ritual.

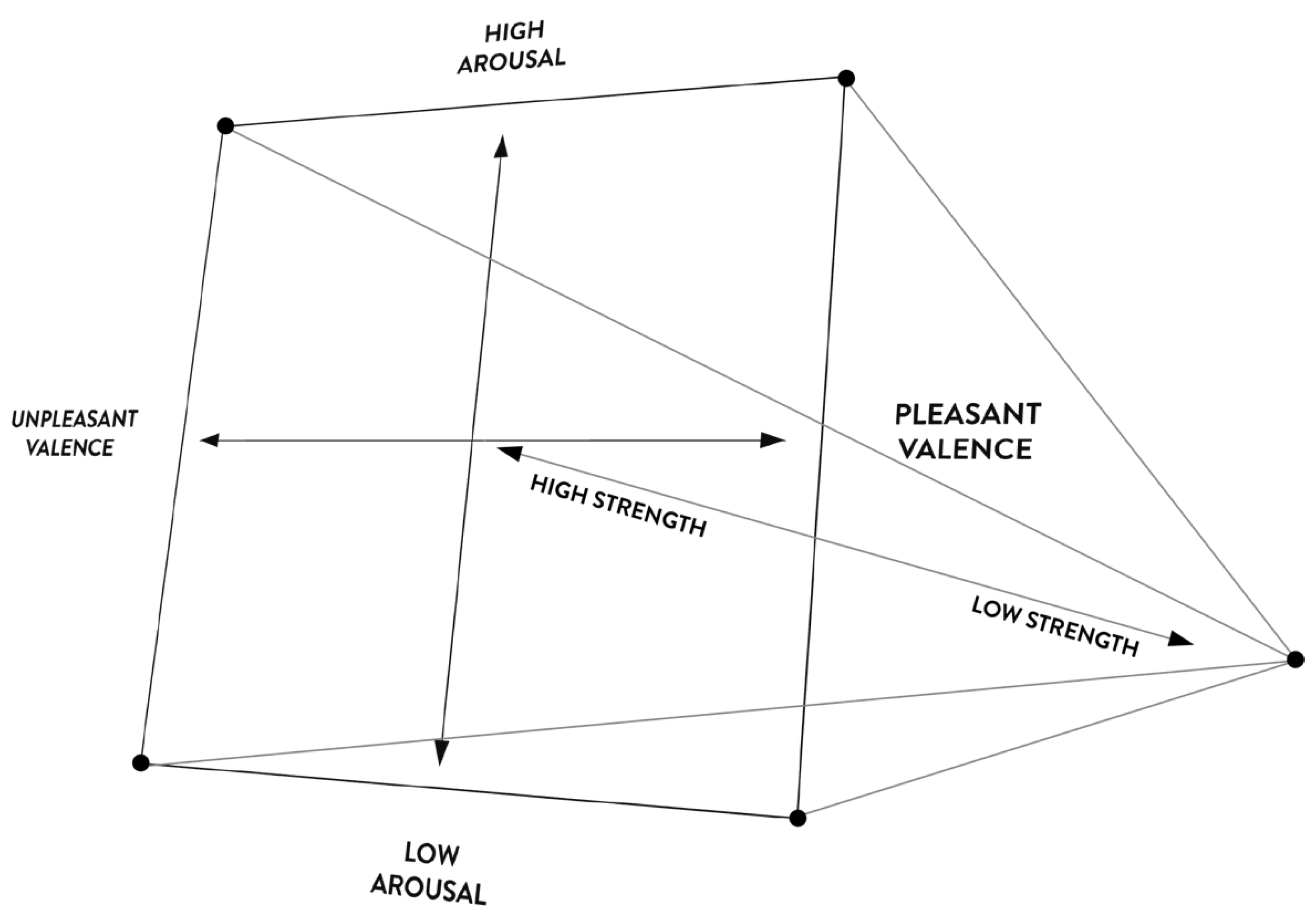

Considering this, it would be appropriate to propose a third dimension to the model; the strength of the emotional ambiance (

Figure 3). The emotional ambiance is stronger when participants in an interaction ritual manifest emotions unanimously, while a lack of coordination in emotional expressions results in a weaker EA. It is also important to consider Collins’ characteristics of an interaction ritual in this context, such as whether the participants share a common focus, if there is a clear boundary against outsiders, and if the participants are within each other’s interactional zones to perceive micro-signals. Therefore, a weak emotional ambiance, along with shortcomings in the aforementioned characteristics, suggests a failed or nonexistent interaction ritual.

If we were to observe emotional coordination in expressions typically associated with happiness, such as synchronous laughter among a group of individuals, this would be an indication of high strength. Conversely, if emotional coordination were only partial, with only a few individuals laughing at the same time while most of the group did not, this would be an indication of lower strength. Furthermore, a group meditation session where all participants are focused and engaged would be characterized as low in arousal but high in strength, since there is a high degree of emotional coordination. Hence, EA represents the strength and character of the emotional coordination in an interaction ritual.

5. The Dynamics of Emotional Ambience and Emotional Energy

Introducing the notion of emotional ambience allows for exploration of an intricate dynamic between emotional ambience and emotional energy. These considerations also illustrate the significance of separating the collective emotions experienced during an interaction ritual and the lasting emotional impact on individuals that persists beyond the ritual.

To clarify, emotional ambience refers to the shared emotions within an interaction ritual, while emotional energy encompasses the individual emotional effects that endure beyond the ritual. It is therefore crucial to separate these two phenomena when analyzing the emotional dynamics of social interactions.

An interaction ritual that is marked by unpleasant emotions may still provide emotional energy to its participants. Consider the example of a funeral, an instance that both Collins and Durkheim reflect over in their inquiries of interaction rituals (

Durkheim and Swain [1915] 2008, p. 385f;

Collins 2004, p. 15f). The funeral brings people together and signifies the interconnectedness of the individuals who gather for the rite. The coordination of actions, such as singing and praying together, along with the exchange of sympathetic words and expressions of compassion and the shared experience of grieving, intensify the common sentiments and strengthen the bond between the mourners.

Cultivating group solidarity is a function of the ritual. As Durkheim argues, the funeral does not serve the deceased, but serves to maintaining the unity of the group that the departed person leaves behind (ibid.). Collins suggests that collective mourning rituals generate emotional energy and strengthens interpersonal connections (

Collins 2004). It is crucial to distinguish between the collective emotions in the situation and its long-term emotional effects, i.e., to avoid equating emotional energy with emotional ambience.

The relationship between emotional energy and emotional ambience is more complex than EE being the result of EA. This arises from the circumstance of the actors engaging in interaction rituals with emotional energy that is carried over from their previous interactions. In his work on interaction ritual theory, Collins introduces the idea of interaction ritual chains, which sheds light on how these interconnected rituals shape social life. The self-confidence, enthusiasm, etc., that arise from the emotional energy that actors have acquired in an interaction ritual form the basis for how the actor approaches the next social situation. The lack of EE can, in turn, cause the actor to withdraw, be listless, etc. In this way, the emotional energy of the actors can affect how an interaction plays out, and thus also how the emotional ambiance develops.

The emotional energy has an impact on the emotional ambiance, and vice versa. However, it is not a straightforward process where the sum of emotional energy determines the resulting emotional ambiance. Instead, emotional energy influences the emotional ambiance, but it does not solely determine it. Interestingly, individuals with initially low emotional energy can still create an intense emotional ambiance, which can ultimately contribute to increasing their emotional energy. Thus, when exploring this topic empirically, it is essential to focus on how emotional coordination occurs during the interaction ritual. This raises methodological questions that require further discussion.

6. Methodology

Emotions are expressed through various forms of action, including gestures, facial expressions, and modulation of voice tone. Conducting empirical investigations into emotional ambience aims to establish a cohesive link between actions and emotions, thereby identifying the specific emotions that manifest within a given situation. Subsequently, this analysis forms the foundation for comprehending the gradual development of emotional coordination among participants engaged in the interactional ritual. The character of these coordinated emotions, including their degree of arousal and valence, constitutes the emotional ambience.

Humans have distinctive abilities for identifying emotional expressions, responding to them, and empathetically mirroring the emotions of others, thus facilitating emotional coordination. Researchers find emotional coordination already in early infants’ communication with their mothers and fathers (

Colonnesi et al. 2012;

Kokkinaki and Markodimitraki 2019). Infants and their caregivers communicate with gaze, facial expressions, vocilazation (ibid.), and gesture (

Retzinger 1991). And eventually, spoken language becomes a primary means of emotional communication, not only semantically but also paralingually, that is, not only what we say but how we speak (ibid., p. 37).

There are various possibilities of observing emotional expressions and communication, with Ekman’s work being the most well-known.

Ekman and Friesen (

1978) worked together for fifty years to develop methods for “unmasking the face” and created The Facial Action Coding System (FACS). This comprehensive system breaks down facial expressions into individual components of muscle movement called Action Units. FACS has been widely used in various fields of research, including psychological and social psychological studies (see the vast citations of

Ekman and Friesen 1978 on, e.g., Google Scholar).

The discerning reader may consider the fact that Ekman and Friesen are associated with discrete emotion theory, which I previously criticized. Nevertheless, even from a critical realist standpoint, Ekman’s and Friesen’s portrayals of facial expressions of emotions can hold significance as one of several indicators for assessing the emotional ambience. Thus, I do not contest the utility of Ekman’s and Friesen’s images in identifying emotional expressions; my critique focuses solely on the assertion that these images identify discrete emotions, implying a limited number of core emotions that are distinct from each other on a neurophysiological basis.

However, it appears reasonable to infer that video-recorded facial expressions ought to be better than isolated still images for identifying emotional expressions within interactions, as film, by definition, constitutes a stream of images in a sequential continuum, allowing the researcher to perceive the gradual formation of facial expressions but also to discern subtle fluctuations occurring at the microscopic level.

Regarding the emotional ambience as conveyed through facial expressions, it is a matter of considering the valence and degree of arousal of the emotions coordinated in the interaction ritual. For instance, if someone smiles, and their smile is met with a smile in return, or if expressions of sadness are met with similar or supportive emotional expressions. In general, the degree of emotional coordination directly correlates with the tangibility of the emotional ambience.

Another method used to analyze emotional coordination is by focusing on prosody, which includes intonation, dynamics, and rhythm of speech (see, e.g.,

Juslin and Scherer 2008). When inferring tone of voice, an interpretivist approach can be used, while speech rhythm can be measured quantitatively by assessing syllables per time unit. Volume dynamics can be evaluated using both qualitative and quantitative data, such as numeric graphs of volume levels in recorded sound. Emotional coordination with regard to prosody refers to actors tuning into each other’s intonation and volume and adapting to each other’s speech rhythms during an interaction ritual.

Scheff and Retzinger have identified additional paralinguistic features that serve as indicators of emotions. In consistency with their postulation of pride and shame as the emotional building blocks of interpersonal relations, they identify several examples of cues for shame, such as lax articulation, hesitation, self-interruption, pauses and silences, laughed words, fragmented speech, and mumbling (

Retzinger 1991;

Scheff and Retzinger 2000). It is worth noting, however, that pride and shame are broad categories that encompass a range of related emotions, including embarrassment, shyness, feelings of insecurity, and foolishness, which are all part of the “shame-family” (

Retzinger 1991, p. 43;

Scheff and Retzinger 2000). While Scheff and Retzinger do not delve into the specifics of pride, as they believe that there is insufficient empirical evidence on the topic, the sociologist and professor of education Jonas Aspelin has developed a corresponding model for pride (

Aspelin 1999).

Scheff and Retzinger have also proposed a connection between emotions and gestures. According to their research, gestures such as lowered or averted eyes, a wrinkled forehead (either vertically or transversely), and hiding behaviors such as covering parts or all of the face with the hand, can indicate shame (

Retzinger 1991;

Scheff and Retzinger 2000). However, the authors caution that the analysis of emotions cannot rely solely on individual gestures or paralinguistic cues; it must take into account a range of related acts.

Similarly, in examining emotional ambience, it is important to consider the combination of gestures, facial expressions, paralinguistic cues, and other relevant factors. The social context and the interplay of various expressions need to be considered in order to determine, for instance, whether a laugh is intended to mock and provoke, or if it represents an expression of joyous attunement. By adopting this principle of analysis, a more comprehensive understanding of emotional communication can be achieved.

Similar to the case with other indicators of emotion, the emotional ambiance concerning gestures and paralinguistic markers is discerned through the utilization of the EA model’s three dimensions. These dimensions encompass the extent of arousal and degree of pleasant/unpleasant valence, alongside the strength of emotional coordination.

When a person takes a step back during a conversation, increases the distance between themselves and the other person, angles their face downwards, and avoids eye contact, it can be a clear signal that unpleasant emotions are present. In the terminology of Scheff and Retzinger, these emotions fall within the spectrum of shame. Additionally, if the other person (Person B) is also expressing emotions that support the emotions being signaled by Person A, this further indicates that the situation is characterized by shame or related emotions. Person A may also speak more hesitantly and quietly and may partly cover their mouth with their hand.

In this example, increasing the distance between the actors in an interaction can mark a range of emotions such as discomfort, insecurity, shame, or other emotions on the unpleasant side of the valence axis. This interaction situation tends to wear on the social bonds between the actors. Conversely, if actors move closer to each other during a conversation, it can suggest pleasant emotions and a successful interaction. The use of space, called proxemics, is a useful tool for analyzing social bonding in interactions (see, e.g.,

Harrigan 2008). It can be used as a methodological parameter to take into account in the analysis of the emotional ambience of an interaction ritual.

As stated, emotional coordination is a key factor in determining the emotional ambiance within a given situation. The phenomenon of emotional contagion is intriguing in this context. Emotional contagion refers to the inclination to automatically imitate the ex-pressions, vocalizations, postures, and movements of another person during interactions, leading to emotional convergence. The mutual contagion of emotions underpins the development of emotional coordination, where both the degree of synchronization (represented by the strength parameter of the EA model) and the quality (valence and degree of arousal) of the coordinated emotions constitute the emotional ambiance.

In summary, there exist several methods for observing emotional communication in interaction rituals. In addition to the content of the dialogue, facial expressions, gesture, gaze, proxemics, prosody, and other paralinguistic phenomena can be focused for identifying emotions, and it is the dynamics of the process in the interaction ritual, the build-up or absence of emotional coordination, that is of interest to discern the emotional ambience.

Additionally, various kinds of self-report are frequently used in empirical research on emotions. Furthermore, physiological variables such as pulse frequency (

Tobin and Ritchie 2012) and thermography (

Clay-Warner and Robinson 2014) could be potential parameters to consider in the analysis of emotional coordination.

Lastly, when examining EA through the theoretical framework of interaction ritual theory, it is important to consider other criteria besides common emotions, such as physical co-presence, a boundary against outsiders, and a common focus of attention, as they are also crucial elements of an interaction ritual.

7. Operationalizing the Concept of Emotional Ambience—An Example

For the purpose of enhancing clarity, the following example demonstrates how methodological tools and the EA model can be utilized to analyze an interaction ritual. The episode is drawn from empirical material; however, it should be noted that the description and analysis provided here are simplified, aiming to serve as a succinct illustration. To reliably capture emotional ambiance, a significantly more detailed transcript of the video-recorded empirical material would be indispensable. Notably, this analysis is specifically oriented towards and confined within the realm of paralinguistic features.

Within the educational context, numerous interaction rituals take place among teachers and students. Each lesson can be regarded as an interaction ritual, and these lessons can, in turn, encompass several smaller interaction rituals. The subsequent episode portrays a variation of an established interaction ritual where the teacher circulates among students engaged in independent work, and the students raise their hands when in need of assistance. In the given example, the task assigned to students is to write a speech about a chosen individual. In this case, the student Ella (14 years old) has opted to write about her sisters and has previously received praise from the teacher, Linda, for her introduction. However, Ella has encountered an impasse and turns to the teacher for guidance:

- 20.52

Ella: But seriously Linda, I’m stuck. I mean, it’s not working. That was like the only good thing I wrote. And then, like, I also wrote… But, I mean, it’s… what… what should I write, like, should I just write, “Oh, I love my sisters because they’re so kind and fun?”

- 21.06

Teacher: No, but you have to have some facts about them, you have to make us feel the same way you do.

- 21.09

E: So should I say then how they are?

- 21.12

T: Mm

- 21.13

E: Then people will think it’s really skewed, because they’re really weird.

- 21.16

T: Mm, but maybe that’s what makes you like them… (short pause)… that you have strong bonds. You have to make us get to know your sisters…

- 21.23

E: Mm.

- 21.23

T: …so that we can feel what you feel.

- 21.24

E: Because after that, I’ll write.

The student, Ella, intercepts the teacher, Linda, as she passes by and exclaims in a perturbed and frustrated tone, “But seriously, Linda, I’m stuck. I mean, it’s not working…etc.”

Interrupting Ella’s rapid and somewhat disjointed flow of words, Linda interjects with a somewhat brusque tone, “No, but you have to have some facts about them, you have to make us feel the same way you do.” Linda stands beside the table, resting on her knuckles, and gazes down at Ella as she speaks.

The dynamics of the subsequent exchange are particularly intriguing as they transition from agitated and curt tones to gentle and ultimately enthusiastic expressions. Ella’s following comment suggests that she is receptive to the teacher’s advice and is beginning to contemplate constructively on her text, “So should I say then how they are?”

Linda’s response, “Mm” (equivalent to “Yes”), remains brief and resolute, which could be interpreted as somewhat stern. Ella’s speech remains rapid, yet the previous degree of agitation seems to have diminished. Her phrasing is more coherent in this and the subsequent paragraph, “Then people will think it’s really skewed, because they’re really weird.” The content of Ella’s statement indicates her contemplation on how to portray her sisters in light of Linda’s guidance, carrying a touch of humor.

It is particularly during the following sequence that a shift in tone occurs. “Mm, but maybe that’s what makes you like them… (short pause)… that you have strong bonds. You have to make us get to know your sisters…”. Linda’s utterance retains a certain firmness initially, but gradually softens, and the tempo mellows during her speech sequence. As Linda speaks, Ella pauses in her movements (21.16–21.23) and gazes thoughtfully into the room. She interjects with a soft and relatively subdued agreement, “Mm”. After also hearing Linda’s subsequent words, spoken with a friendly and calm tone, “…so that we can feel what you feel.”, Ella seems to come alive again. Her voice becomes infused with enthusiasm as she proceeds to discuss her text and continues the dialogue.

The softening intonation during Linda’s speech sequence (21.16–21.23) can be attributed to Ella’s momentary stillness and her transformation of emotional expression while she gazes thoughtfully into the room. This is a low-arousal expression, devoid of the noticeable frustration that was present just seconds earlier. In this context, Linda’s softening tone can be perceived as responsiveness and a reflection of Ella’s microsignals of emotion, which, in turn, were influenced by Linda’s words. Each gesture is both a response and a forward-propelling action—an instantaneous reaction intertwined with purposeful action. It represents a dynamic interplay and a flow of microsignals between them, an emotional ambiance that continually evolves through their interaction; the high level of arousal that decreases during the episode, coupled with the transition from an unpleasant to a pleasant valence as the brusque ambiance transforms into a gentle and agreeable one.

Throughout the episode, Linda and Ella exhibit an attunement to each other’s intonation, volume, and speech rhythm, showcasing their dynamic adaptation to one another. This entrainment highlights a high level of emotional coordination, as depicted by the strength parameter in the EA model.

As previously stated, this excerpt provides an initial insight into the potential of directing attention towards paralinguistic features, with a particular emphasis on intonation in this specific instance. This focus allows for the analysis of emotional ambiance dynamics, specifically the strength of emotional coordination and the variations in arousal and valence. Naturally, the incorporation of facial expressions, gestures, and other paralinguistic elements into the analysis would undoubtedly enhance the comprehensiveness and robustness of the analytical framework.

In relation to Collin’s theoretical framework, this analysis sheds light on the situational and interactional foundations that contribute to the development of emotional energy and the strengthening of social bonds between the teacher and the student. It is noteworthy that an extended analysis should also encompass considerations of (1) bodily copresence, (2) a common focus (see above), and other pertinent aspects of Collin’s theoretical framework.

8. Conclusions

As a complement to Collins’s theory of interaction ritual chains, I have proposed a three-dimensional model to be employed as an analytical tool for exploring the emotional ambience within a social situation. Furthermore, I have discussed several methodological approaches to observe and analyze the strength and character of emotional coordination among actors during an interaction ritual. This paper advocates for the significance of differentiating between emotional energy and emotional ambience. Emotional ambience refers to the strength and quality of emotional coordination during an interaction ritual, whereas emotional energy pertains to the enduring emotional outcome resulting from the said ritual. The concept of emotional ambience, in conjunction with its associated theoretical and methodological frameworks, enables us to recognize that situations characterized by unpleasant emotions can indeed give rise to emotional energy. The crucial factor determining the development of group solidarity and emotional energy is the emotional attunement among actors, their mutual support and reflection of each other’s emotional expressions, regardless of whether they involve sadness or joy.

The emotional ambience model serves as a means to comprehend the constituents (microsignals such as gestures, tone of voice, etc.) that contribute to changes in the arousal, valence, and strength of emotional coordination. It thus offers a comprehensive framework for understanding the foundational elements within an interaction ritual that evoke emotional energy and cultivate experiences of group solidarity. Conversely, it can shed light on the elements contributing to an unsuccessful establishment of emotional coordination, leading to diminished emotional energy and group solidarity.

In an upcoming article, I will utilize the concept of emotional ambience in conjunction with Collins’s theory to analyze empirical data which comprises interactions between a teacher and students in an elementary school context.