Rethinking the Unthinkable: A Delphi Study on Remote Work during COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Positive Implications of Remote Work

2.2. Negative Implications of Remote Work

2.3. The Italian Context

2.4. Aim of the Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Analysis

4. Results

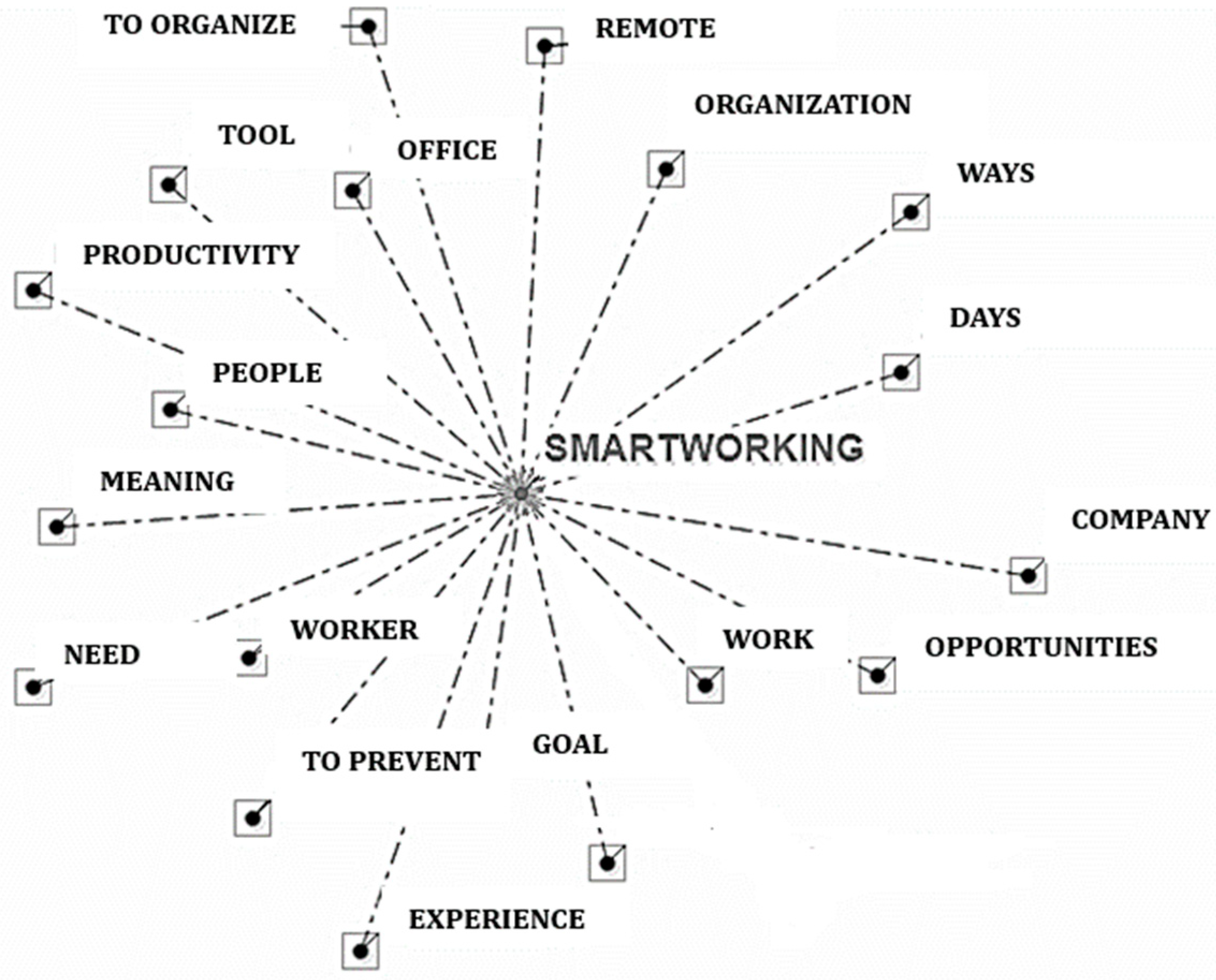

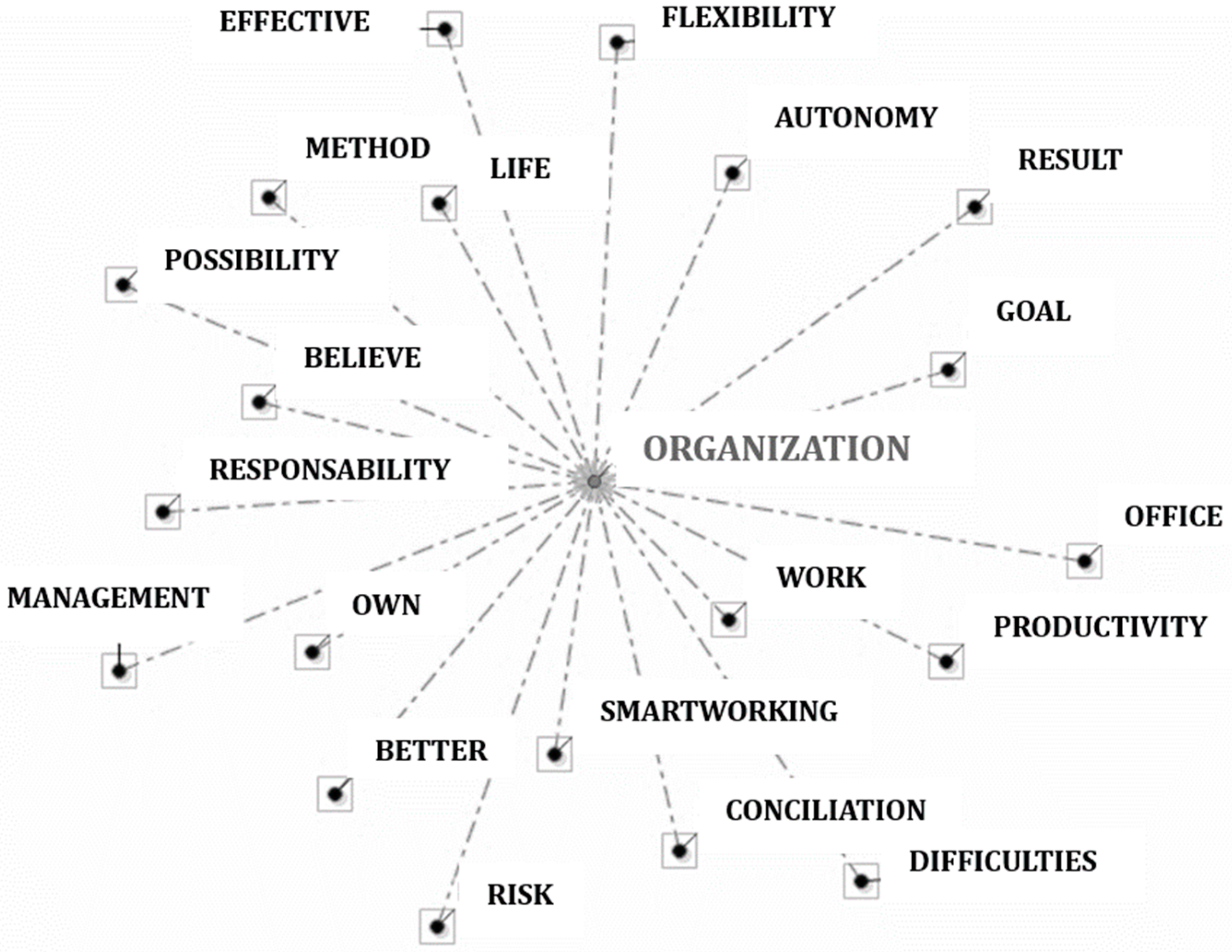

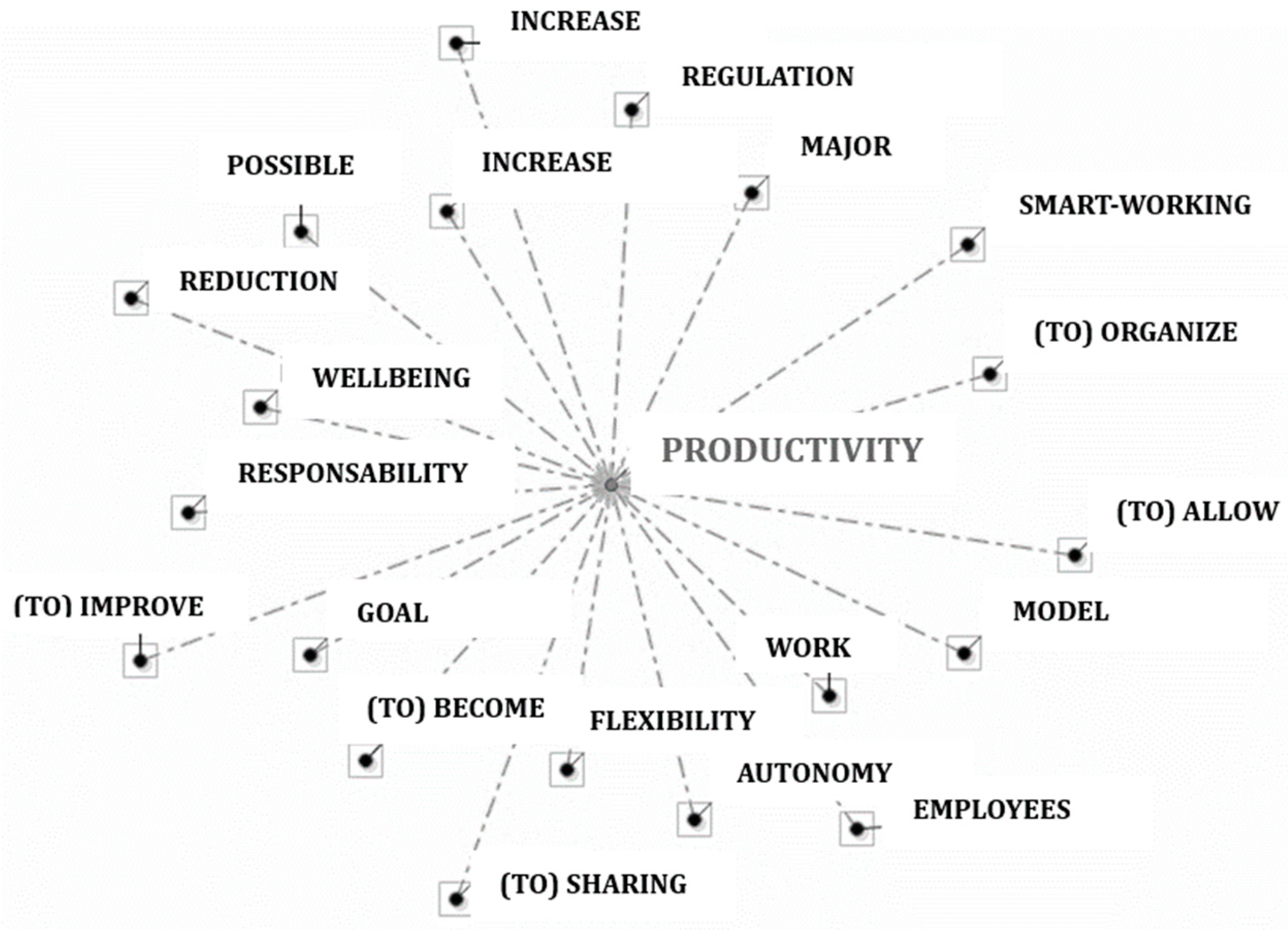

4.1. Qualitative Results

4.2. Quantitative Analysis

Analysis of Occurrence and Co-Occurrence

5. Discussion

6. Limits and Future Perspectives

7. Theoretical and Practical Implication

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adeosun, Oluyemi Theophilus, and Adeku Salihu Ohiani. 2020. Attracting and recruiting quality talent: Firm perspectives. Rajagiri Management Journal 14: 107–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Tammy D., Timothy D. Golden, and Kristen M. Shockley. 2015. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 16: 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avogaro, Matteo. 2018. Right to disconnect: French and Italian proposals for a global issue. Law Journal: Social and Labor Relations 4: 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabaschi, Barbara, Laura Barbieri, Franca Cantoni, Silvia Platoni, and Roberta Virtuani. 2022. Remote working in Italian SMEs during COVID-19. Learning challenges of a new work organization. Journal of Workplace Learning 34: 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beno, Michal. 2021. Analysis of Three Potential Savings in E-Working Expenditure. Frontiers in Sociology 6: 675530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, Zahid Hussain, Uqba Yousuf, and Nuzhat Saba. 2022. The Implications of Telecommuting on Work-Life Balance: Effects on Work Engagement and Work Exhaustion. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-1642674/v1 (accessed on 22 August 2023). [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Nicholas. 2020. How Working from Home Works Out. Stanford: Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, p. 8. Available online: https://siepr.stanford.edu/publications/policy-brief/how-working-home-works-out (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Bloom, Nicholas, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying. 2015. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Quarterly Journal of Economics 130: 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulkedid, Rym, Hendy Abdoul, Marine Loustau, Olivier Sibony, and Corinne Alberti. 2011. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 6: e20476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, Jennifer. 2018. Interviews, focus groups, and Delphi techniques. In Advanced Research Methods for Applied Psychology. Edited by Paula Brough and Robert A. Schweitzer. London: Routledge, pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cannito, Maddalena, and Alice Scavarda. 2020. Childcare and remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ideal worker model, parenthood and gender inequalities in Italy. Italian Sociological Review 10: 801–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cortini, Michela. 2014. Mix-method research in applied psychology. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 5: 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortini, Michela, and Stefania Tria. 2014. Triangulating qualitative and quantitative approaches for the analysis of textual materials: An introduction to T-lab. Social Science Computer Review 32: 561–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Jacqueline, and Milena Bobeva. 2005. A generic toolkit for the successful management of Delphi studies. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 3: 103–16. [Google Scholar]

- De Vincenzi, Clara, Martina Pansini, Bruna Ferrara, Ilaria Buonomo, and Paula Benevene. 2022. Consequences of COVID-19 on Employees in Remote Working: Challenges, Risks and Opportunities An Evidence-Based Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 11672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, Simone, Gianluca Viola, Ferdinando Toscano, and Salvatore Zappalà. 2021. Not all remote workers are similar: Technology acceptance, remote work beliefs, and wellbeing of remote workers during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunatchik, Allison, Kathleen Gerson, Jennifer Glass, Jerry A. Jacobs, and Haley Stritzel. 2021. Gender, parenting, and the rise of remote work during the pandemic: Implications for domestic inequality in the United States. Gender & Society 35: 194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Elvie, Maria. 2019. The influence of organizational culture, compensation and interpersonal communication in employee performance through work motivation as mediation. International Review of Management and Marketing 9: 133. [Google Scholar]

- Eurofound. 2021. Living, Working and COVID-19 (Update April 2021): Mental Health and Trust Decline across EU as Pandemic Enters Another Year. In Eurofound Factsheet. Vol. EF/21/064/. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/84c20388-ccbb-11eb-ac72-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 22 August 2023). [CrossRef]

- Fonner, Kathrin L. 2015. Communication and Telework. In The International Encyclopedia of Interpersonal Communication. Edited by James C. McCroskey and Virginia P. Richmond. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gajendran, Ravi S., and David A. Harrison. 2007. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology 92: 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanti, Teresa Mpsyc, Gloria Guidetti, Eleonora Mpsyc Mazzei, Salvatore Zappalà, and Ferdinando Mpsyc Toscano. 2021. Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: The impact on employees’ remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 63: e426–e432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, Teresa, and Michela Cortini. 2019. Work as a recovery factor after earthquake: A mixed-method study on female workers. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 28: 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, Teresa, Clara De Vincenzi, Ilaria Buonomo, and Paula Benevene. 2023. Digital Transformation: Inevitable Change or Sizable Opportunity? The Strategic Role of HR Management in Industry 4.0. Administrative Sciences 13: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Thomas J., Leanne E. Atwater, Dustin Maneethai, and Juan M. Madera. 2022. Supporting the productivity and wellbeing of remote workers: Lessons from COVID-19. Organizational Dynamics 51: 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, Sara, Carmel Shachar, Peter R. Chai, and I. Glenn Cohen. 2020. Regulatory, safety, and privacy concerns of home monitoring technologies during COVID-19. Nature Medicine 26: 1176–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanis, Eleftherios. 2018. The Relationship between Flexible Employment Arrangements and Workplace Performance in Great Britain. International Journal of Manpower 39: 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, Timothy D., John F. Veiga, and Zeki Simsek. 2006. Telecommuting’s differential impact on work-family conflict: Is there no place like home? Journal of Applied Psychology 91: 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Barbara, Melanie Jones, David Hughes, and Anne Williams. 1999. Applying the Delphi technique in a study of GPs information requirements. Health and Social Care in the Community 7: 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Chia-Chien, and Brian A. Sandford. 2007. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 12: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Jankelová, Nadežda. 2022. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Trust, Job Autonomy and Team Connectivity: Implications for Organizational Innovativeness. Engineering Economics 33: 264–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, Gerald C., Rich Nanda, Anh Phillips, and Jonathan Copulsky. 2021. Redesigning the post-pandemic workplace. MIT Sloan Management Review 62: 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney, Lisa B., Bethany L. Ames, Mary S. Huang, Torunn Yock, Daniel C. Bowers, Larissa Nekhlyudov, David Williams, Melissa M. Hudson, and Nicole J. Ullrich. 2022. Consensus recommendations for managing childhood cancer survivors at risk for stroke after cranial irradiation: A Delphi study. Neurology 99: e1755–e1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knardahl, Stein, and Jan Olav Christensen. 2022. Working at home and expectations of being available: Effects on perceived work environment, turnover intentions, and health. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 48: 99. [Google Scholar]

- Kodish, Slavica. 2014. Communicating Organizational Trust: An Exploration of the Link Between Discourse and Action. International Journal of Business Communication 54: 347–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, Glen E., Elaine C. Hollensbe, and Mathew L. Sheep. 2009. Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work-home interface via boundary work tactics. Academy of Management Journal 52: 704–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, Banita, Yogesh K. Dwivedi, and Markus Haag. 2021. Working from home during covid-19: Doing and managing technology-enabled social interaction with colleagues at a distance. Information Systems Frontiers 25: 1333–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancia, F. 2004. Strumenti per l’analisi dei testi. Introduzione all’uso di T-LAB. Milano: Franco Angeli, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lazauskaite-Zabielske, Jurgita, Arunas Ziedelis, and Ieva Urbanaviciute. 2022. When working from home might come at a cost: The relationship between family boundary permeability, overwork climate and exhaustion. Baltic Journal of Management 17: 705–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker Martin, Brittany, and Rhiannon MacDonnell. 2012. Is telework effective for organizations? Management Research Review 35: 602–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, Monica, Emanuela Ingusci, Fulvio Signore, Amelia Manuti, Maria Luisa Giancaspro, Vincenzo Russo, Margherita Zito, and Claudio G. Cortese. 2020. Wellbeing costs of technology use during COVID-19 remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale. Sustainability 12: 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreuil, Sylvie, and Katherine Lippel. 2003. Telework and occupational health: A Quebec empirical study and regulatory implications. Safety Science 41: 339–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzio, Daniel, and Jonathan Doh. 2021. COVID-19 and the future of management studies. Insights from leading scholars. Journal of Management Studies 57: 1725–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Teresa, and Cornelia Niessen. 2019. Self-leadership in the context of part-time teleworking. Journal of Organizational Behavior 40: 883–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Bridget C., Ilene B. Harris, Thomas J. Beckman, Darcy A. Reed, and David A. Cook. 2014. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine 89: 1245–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paais, Maartje, and Jozef R. Pattiruhu. 2020. Effect of motivation, leadership, and organizational culture on satisfaction and employee performance. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business 7: 577–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansini, Martina, Ilaria Buonomo, Clara De Vincenzi, Bruna Ferrara, and Paula Benevene. 2023. Positioning Technostress in the JD-R model perspective: A systematic literature review. Healthcare 11: 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Sunyoung, Shinhee Jeong, and Dae Seok Chai. 2021. Remote e-workers’ psychological well-being and career development in the era of COVID-19: Challenges, success factors, and the roles of HRD professionals. Advances in Developing Human Resources 23: 222–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentland, Brian T., Martha S. Feldman, Markus C. Becker, and Peng Liu. 2012. Dynamics of organizational routines: A generative model. Journal of Management Studies 49: 1484–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Manuela Pérez, Angel Martínez Sánchez, Pilar de Luis Carnicer, and María José Vela Jiménez. 2005. The Differences of Firm Resources and the Adoption of Teleworking. Technovation 25: 1476–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radakovich, Patricia S. 2016. The Relationship between Organizational Culture, Intrinsic Motivation, and Employee Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Detroit: Wayne State University. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Brie Weiler. 2022. The Environmental Impacts of Remote Work: Stats and BenefitsFlexJobs. Flexjobs. Available online: https://www.flexjobs.com/blog/post/telecommuting-sustainability-how-telecommuting-is-a-green-job/ (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Ruhle, Sascha Alexander, and René Schmoll. 2021. COVID-19, telecommuting, and (virtual) sickness presenteeism: Working from home while ill during a pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholl, Wolfgang, Christine König, Bertolt Meyer, and Peter Heisig. 2004. The future of knowledge management: An international delphi study. Journal of Knowledge Management 8: 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secunda, Paul M. 2019. The employee right to disconnect. Notre Dame Journal of International & Comparative Law 9: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sheveleva, Anna, and Evgeny Rogov. 2021. Organization of remote work in the context of digitalization. In E3S Web of Conferences. Ulis: EDP Sciences, vol. 273, p. 12042. [Google Scholar]

- Smite, Darja, Nils Brede Moe, Jarle Hildrum, Javier Gonzalez-Huerta, and Daniel Mendez. 2023. Work-from-home is here to stay: Call for flexibility in post-pandemic work policies. Journal of Systems and Software 195: 111552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, Paola, Amelia Manuti, Carmela Buono, and Chiara Ghislieri. 2021. The good, the bad and the blend: The strategic role of the “middle leadership” in work-family/life dynamics during remote working. Behavioral Sciences 11: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, Janka I., Harry Garretsen, and Joris Lammers. 2021. Leading and working from home in times of COVID-19: On the perceived changes in leadership behaviors. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 29: 208–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangaratinam, Shakila, and Charles W. E. Redman. 2005. The delphi technique. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 7: 120–25. [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, Ferdinando, and Salvatore Zappalà. 2020. Social Isolation and Stress as Predictors of Productivity Perception and Remote Work Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Concern about the Virus in a Moderated Double Mediation. Sustainability 12: 9804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, Ferdinando, Salvatore Zappalà, and Teresa Galanti. 2022. Is a good boss always a plus? LMX, family–work conflict, and remote working satisfaction during the Covid-19 pandemic. Social Sciences 11: 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, Tinne, Ronny Verhoogen, Maarten Sercu, Anja Van den Broeck, Elfi Baillien, and Lode Godderis. 2017. Not Extent of Telecommuting, But Job Characteristics as Proximal Predictors of Work-Related Well-Being. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 59: e180–e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virgiawan, Ade Riandi, Setyo Riyanto, and Endri Endri. 2021. Organizational culture as a mediator motivation and transformational leadership on employee performance. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 10: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Bergen, Clarence W., and Martin S. Bressler. 2019. Work, non-work boundaries and the right to disconnect. The Journal of Applied Business and Economics 21: 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Bin, Yukun Liu, Jing Qian, and Sharon K. Parker. 2021. Achieving effective remote working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology 70: 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Wendy, Leslie Albert, and Qin Sun. 2020. Employee isolation and telecommuter organizational commitment. Employee Relations: The International Journal 42: 609–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Ada Hiu Kan, Joyce Oiwun Cheung, and Ziguang Chen. 2020. Promoting effectiveness of ‘working from home’: Findings from Hong Kong working population under COVID-19. Asian Education and Development Studies 10: 210–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Best Practices | Worst Practices |

|---|---|

| Involvement of the workers in the clear definition of the company mission and goals | Poor organizational communication and inefficient communication strategy |

| Transparency in defining the criteria for employees opt for remote work, clearly stated in the employment contract | Lack of clarity and transparency in the remote work policy, which can create confusion and uncertainty among employees and erode trust and loyalty to the organization |

| Constantly updating technology equipment and IT support | Outdated technology equipment and inadequate IT support |

| Implementation of a monitoring and evaluation system that is not based on surveillance (management by objectives) | Absence of a system for performance assessment and regular feedback |

| Creation of a workplace culture that enables employees to effectively balance work responsibilities with personal and family commitments | Workplace culture based on work-life imbalance (excessive demands and little flexibility in work schedules) |

| Enhancing internal communication and mutual trust | Lack of coordination and communication among workers |

| LEMMA | COEFF | C.E.(A) | C.E.(AB) | CHI2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work | 0.589 | 163 | 82 | 0.464 |

| To organize | 0.349 | 54 | 28 | 0.264 |

| People | 0.34 | 29 | 20 | 5.372 |

| Office | 0.328 | 20 | 16 | 8.504 |

| Opportunities | 0.3 | 21 | 15 | 4.721 |

| Goal | 0.295 | 28 | 17 | 1.806 |

| Need | 0.232 | 10 | 8 | 4.07 |

| Productivity | 0.229 | 27 | 13 | 0.005 |

| Time management | 0.190 | 29 | 11 | 1.548 |

| Culture | 0.183 | 9 | 6 | 1.198 |

| LEMMA | COEFF | C.E.(A) | C.E.(AB) | CHI2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work | 0.522 | 163 | 49 | 17.918 |

| Smart working | 0.522 | 163 | 49 | 17.918 |

| Work-life conciliation | 0.34 | 29 | 20 | 5.372 |

| Productivity | 0.262 | 27 | 10 | 3.914 |

| Responsibility | 0.246 | 15 | 7 | 5.583 |

| Flexibility | 0.219 | 19 | 7 | 2.588 |

| Results | 0.218 | 14 | 6 | 3.702 |

| Risk_management | 0.206 | 18 | 4 | 5.126 |

| Sharing | 0.180 | 6 | 3 | 2.772 |

| Monitoring | 0.180 | 6 | 3 | 2.772 |

| Regulation | 0.180 | 6 | 3 | 2.772 |

| LEMMA | COEFF | C.E.(A) | C.E.(AB) | CHI2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 0.302 | 4 | 2 | 19.55 |

| Productivity | 0.29 | 27 | 5 | 13.843 |

| Sharing | 0.27 | 5 | 2 | 14.937 |

| Innovation | 0.261 | 12 | 3 | 12.311 |

| Awareness | 0.246 | 6 | 2 | 11.872 |

| Trust | 0.246 | 6 | 2 | 11.872 |

| Improvement | 0.228 | 7 | 2 | 9.694 |

| Goal | 0.228 | 28 | 4 | 7.024 |

| Quality of life | 0.213 | 36 | 2 | 8.068 |

| Smart working | 0.193 | 119 | 7 | 1.019 |

| Work-life conciliation | 0.180 | 28 | 3 | 2.83 |

| LEMMA | COEFF | C.E.(A) | C.E.(AB) | CHI2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work | 0.317 | 163 | 21 | 1.649 |

| Flexibility | 0.309 | 19 | 7 | 13.911 |

| Goal | 0.291 | 28 | 8 | 9.85 |

| Wellbeing | 0.29 | 11 | 5 | 13.843 |

| Model | 0.258 | 5 | 3 | 12.421 |

| (To) Improve | 0.204 | 8 | 3 | 5.873 |

| Sharing | 0.172 | 5 | 2 | 4.343 |

| Autonomy | 0.154 | 20 | 3 | 1.621 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galanti, T.; Ferrara, B.; Benevene, P.; Buonomo, I. Rethinking the Unthinkable: A Delphi Study on Remote Work during COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090497

Galanti T, Ferrara B, Benevene P, Buonomo I. Rethinking the Unthinkable: A Delphi Study on Remote Work during COVID-19 Pandemic. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(9):497. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090497

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalanti, Teresa, Bruna Ferrara, Paula Benevene, and Ilaria Buonomo. 2023. "Rethinking the Unthinkable: A Delphi Study on Remote Work during COVID-19 Pandemic" Social Sciences 12, no. 9: 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090497

APA StyleGalanti, T., Ferrara, B., Benevene, P., & Buonomo, I. (2023). Rethinking the Unthinkable: A Delphi Study on Remote Work during COVID-19 Pandemic. Social Sciences, 12(9), 497. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090497