Paid Parental Leave in Correlation with Changing Gender Role Attitudes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Research Background and Research Question

3. Data and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Advantages for Parents with Infants, Challenges for Parents with School-Aged Children during the Pandemic

“Work assignments were sent to my mobile phone, even on Saturdays at 4 a.m., I remember, and the German teacher sent the assignments for the next week by e-mail, right? And, well, luckily, I also, because I am also a trained mediator, had a flipchart at home, and since the children had such big rooms, I put a big table there for the two children, like at school, the baby on my arm, and studied with them on the flipchart, did homework—I don’t know—explained grammar”.(Couple E2/2022, Miriam, 38, three children: twins aged 13 and one 2.5-year-old infant)

“Well, they [her parents] were also wondering. But yes, of course, that was already the case with me, I’m also in Lower Austria and there it’s just not usual at all. And there is kindergarten from the age of 2.5, and I […] had to listen to negative critique: yes, putting the child in daycare so early”.(Couple U/2022, Esther, 40, research employee in an NGO, one child; Max, 42, IT sector, one child)

Esther: “Ah, so the first wave (meaning the first hard lockdown in Austria, authors’ remark) was already chaos because we… It wasn’t closed for so long. In Vienna, there was also emergency care. We had him at home for about six weeks”.

Max: “About, yes, five to six weeks, yes”.

Esther: “Yes, so spatially we had no problem because the apartment is large, he has his own study there, and one in the kitchen. And (takes a deep breath) how should I say? At first, we said: ‘We’ll do it somehow, whoever has the time will take care of the son, so if someone has a meeting, then it’s the other person’s turn.’ But then I already had the feeling that that wouldn’t work, because as a manager he has many more meetings, and then I don’t get to work at all. Then we tried to make a plan that we really: So who has meeting when? Who can look after him for how many hours? That worked out halfway. I mean, I have a little bit more then”.

Max: “Yes, I would say it was 60:40 in any case, yes”.

4.2. Counterforces and Parental Strategies for Realizing an Equitable Distribution of Infant Care Responsibilities

“As a tax consultant, you have your clients, you know your clients and have to be there for them, and you don’t want to give away the good ones”.(Couple R/2021, Nadia, 35, tax consultant, two infants)

“Because my level is absolutely not reached. So, I…, I really wanted to go back in January, in order not to lose the one client I like very much. That’s why I decided to go to work two weeks earlier than planned. And I knew, […] if I don’t come back, I will be labeled immediately and I will have to build it all up again”.(Couple R/2021, Nadia, 35, tax consultant, two infants)

“’Then, I could stop working for you right away,’ so to speak [grins]. And that was that”.(Couple R/2022, Karl, 37, architect, two infants)

“It was already the case that the new person, who would become my supervisor in the future—which means next year when my direct supervisor retires—had already made some sexist statements. And he said, for example, whether I think that I will manage my job with my family, with the children. And then, five minutes after that conversation, I thought that I wouldn’t want to work for the company if they treated me like that. But I would also have liked to change jobs regardless of that. It all came together”.(Couple J2/2022, Theresa, 40, two children, board member at a major Austrian construction company; at the time of our interview, Theresa intended to change employers after being on parental leave with her second child)

4.3. Men’s Motives and Willingness to Claim Parental Leave and Childcare Benefits

“I am in the wood industry, which is one of the lowest paid industries, and Tina is in one of the best paid, in the software sector, […] in the IT sector, yes?”(Couple T/2022, Dieter, 44, quality control, wood sector, two children)

“We confirmed that I had already consumed all my yearly days of sick leave before my partner asked for two days off to take care of our twins”.(2021/couple X, Mara, 49, researcher, two children)

“Right now, it’s mostly four days a week when I take him over completely. And completely means we agreed that I take him over at 9 a.m. and then at 3 p.m., mostly, 3 or 4 p.m. Eva comes along”.(Couple B/2021, Bert, 32, video production/artists’ collective, one child)

“And on Fridays, I had my day off, which means, on Fridays, mom would take him over, my turn, it wouldn’t start until the afternoon”.(Couple M/2021, Murat, 36, construction work, two children)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This aspect was not in the foreground of our research when applying for research funding and planning the empirical research in 2019–2020. |

| 2 | In a second empirical wave, a selected number of parents will be interviewed in individual interviews. These results will be shared at a later stage of the funding period, ending in 2025 (https://genfam.univie.ac.at/en/ (accessed on 30 August 2023). |

| 3 | Votum of the Ethical Committee of the University of Vienna, Approval Code: 00663; Approval Date: 11 May 2021. |

| 4 | Prior local research funding (Municipal of Vienna, Austria): Hochschuljubiläumsstiftung der Stadt Wien H-275602/2013 and H-284605/2015), and Magistrat der Stadt Wien: MA 7-184748/13, MA 7-184748/13, MA 7-180868/14, MA 7-944695/16 and MA 7-288196/20. |

| 5 | Minor or low-income employment is defined as regular employment (employment for one month or an indefinite period) with maximum earnings of 500.91 euros per calendar month (1 January 2023). In recent years, the income ceiling has been slightly lower. Special payments (such as holiday allowances and Christmas bonuses) to which employees are usually entitled are not taken into account in these remuneration limits. Depending on the individual’s labor market position, branch of employment, and prior income, minor employment typically involves working 5–8 h per week. |

References

- Abendroth, Anja-Kristin. 2022. Transitions to parenthood, flexible working and time-based work-to-family conflicts: A gendered life course and organisational change perspective. Journal of Family Research 34: 1033–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, Joan. 1990. Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies. A Theory of Gendered Organizations. Gender & Society 4: 139–58. [Google Scholar]

- Acker, Joan. 2009. From Glass Ceiling to Inequality Regimes. Du plafond de verre aux régimes d’inégalité. Sociologie du travail 2: 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, Joan. 2012. Gendered Organizations and Intersectionality: Problem and Possibilities. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion. An International Journal 31: 214–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemann, v. Annette, Beaufaӱs Sandra, and Oechsle Mechtild. 2017. Anspruchsbewusstsein und verborgene Regeln in Unternehmenskulturen [Involved fatherhood in work organizations—Sense of entitlement and hidden rules in organizational cultures]. Zeitschrift für Familienforschung 29: 72–89. [Google Scholar]

- Augusto, Amélia, Dulce Morgado Neves, and Vera Henriques. 2023. Breastfeeding experiences and women’s self-concept: Negotiations and dilemmas in the transition to motherhood. Frontiers in Sociology 8: 1130808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulenbacher, Brigitte, Riegraf Birgit, and Theobald Hildegard. 2014. Sorge: Arbeit, Verhältnisse, Regime. Baden: Nomos. [Google Scholar]

- Brandth, Berit, and Kvande Elin. 2019. Flexibility: Some consequences for fathers’ caregiving. In 17th International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2021. Edited by Alison Koslowski, Sonja Blum, Ivana Dobrotić, Gayle Kaufman and Peter Moss. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannen, Julia, Charlotte Faircloth, Claire Jones, Margaret O’Brien, and Katherine Twamley. 2023. Change and continuity in men’s fathering and employment practices: A slow gender revolution. In Social Research for Our Times: Thomas Coram Research Unit Past, Present and Future. Edited by Claire Cameron, Alison Koslowski, Alison Lamont and Peter Moss. London: UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brighouse, Harry, and Erik Olin Wright. 2008. Strong Gender Egalitarianism. Politics & Society 36: 360–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumley, Krista M. 2018. Involved’ Fathers, ‘Ideal’ Workers? Fathers’ Work–Family Experiences in the United States. In Fathers, Childcare and Work: Cultures, Practices and Policies (Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research). Edited by Rosy Musumei and Arianna Santero. Emerald Series; Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 12, pp. 209–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cervera-Gasch, Águeda, Mena-Tudela Desirée, Leon-Larios Fatima, Felip-Galvan Neus, Rochdi-Lahniche Soukaina, Andreu-Pejó Laura, González-Chordá, and Víctor Manuel. 2020. Female Employees’ Perception of Breastfeeding Support in the Workplace, Public Universities in Spain: A Multicentric Comparative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, Sara, Aldrich Matthew, O’Brien Margaret, Speight Svetlana, and Poole Eloise. 2016. Britain’s slow movement to a gender egalitarian equilibrium: Parents and employment in the UK 2001–13. Work, Employment and Society 30: 838–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, Isabella, and Elisabetta Ruspini. 2016. Balancing Work and Family in a Changing Society: The Fathers’ Perspective. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing, Helene. 2016. Gender Equality in the Division of Work: How to Assess European Leave Policies Regarding their Compliance with an Ideal Leave Model. Journal of European Social Policy 26: 234–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derndorfer, Judith, Disslbacher Franziska, Lechinger Vanessa, Mader Katharina, and Six Eva. 2021. Home, sweet home? The impact of working from home on the division of unpaid work during the COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS ONE 16: e0259580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, Francine, and Ruth A Gaunt. 2020. Creating Equality at Home: How 25 Couples around the World Share Housework and Childcare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Di Battista, Silvia. 2023. Gender Role Beliefs and Ontologization of Mothers: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Social Sciences 12: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucet, Andrea. 2016. “The choice was made for us”: Stay-At-Home Dads (SAHDs) and Relationalities of Work and Care in Canada and the United States. In Balancing Work and Family in a Changing Society: The Fathers’ Perspective. Edited by Isabella Crespi and Elisabetta Ruspini. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Duvander, Ann-Zofie. 2014. How Long Should Parental Leave Be? Attitudes to Gender Equality, Family, and Work as Determinants of Women’s and Men’s Parental Leave in Sweden. Journal of Family Issues 35: 909–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EIGE—European Institute for Gender Equality. 2021. Gender Inequalities in Care and Consequences for the Labour Market. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/gender-ine-qualities-care-and-consequences-labour-market (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Eliott, Karla. 2016. Caring masculinities: Theorizing an emerging concept. Men and Masculinities 19: 240–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evertsson, Marie, and Daniela Grunow. 2019. Swimming against the tide or going with the flow? Stories of work-care practices, parenting norms and the importance of policies in a changing Europe. In New Parents in Europe: Work-Care Practices, Gender Norms and Family Policies. Edited by Danile Grunow and Marie Evertsson Marie. Cheltenham and Northhampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 226–46. [Google Scholar]

- Eydal, Gudný Björk, and Tine Rostgaard. 2014. Fatherhood in the Nordic Welfare States. Comparing Care Policies and Practice. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth, Charlotte. 2021a. Couples’ Transitions to Parenthood: Gender, Intimacy and Equality. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faircloth, Charlotte. 2021b. When equal partners become unequal parents: Couple relationships and intensive parenting culture. Families, Relationships and Societies 10: 231–48. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G. 1978. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley: The Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, Barney G., and Anselm L. Strauss. 1998. Grounded Theory. Strategien Qualitativer Forschung. Bern: Huber. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider, Frances, Bernhardt Eva, and Lappegård Trude. 2014. Studies of men’s involvement in the family, Part 1: Introduction. Journal of Family Issues 35: 879–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldscheider, Frances, Bernhardt Eva, and Lappegård Trude. 2015. The gender revolution: A framework for understanding changing family and demografic behavior. Population and Development Review 41: 207–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Patricia. 2020. Black Mothers and Attachment Parenting. Bristol: Bristol University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausen, Karin. 1976. Die Polarisierung der “Geschlechtscharaktere”. Eine Spiegelung der Dissoziation von Erwerbs- und Familienleben. In Sozialgeschichte der Familie in der Neuzeit Europas. Neue Forschungen (Industrielle Welt, Bd. 21). Edited by Werner Conze. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, pp. 363–93. [Google Scholar]

- Koppetsch, Cornelia, and Sarah Speck. 2015. Wenn der Mann kein Ernährer mehr ist. Geschlechterkonflikte in Krisenzeiten. Berlin: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Koslowski, Alison, Blum Sonja, Dobrotić Ivana, Kaufman Gayle, and Moss Peter. 2022. 18th International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2022. Available online: https://www.leavenetwork.org/annual-review-reports/review-2022/ (accessed on 11 March 2023).

- Kreimer, Margareta. 2018. Free to choose, free to lose: Macht, Diskriminierung und die Arbeitsteilung zwischen den Geschlechtern. In Kapitalismus und Freiheit. Jahrbuch Normative und institutionelle Grundfragen der Ökonomik, Band 17. Edited by Richard Sturn, Katharina Hirschbrunn and Ulrich Klüh. Marburg: Metropolis, pp. 117–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ladge, Jamie J., Beth K. Humberd, Baskerville Watkins Marla, and Harrington Brad. 2015. Updating the organization man: An examination of involved fathering in the workplace. Academy of Management Perspectives 2: 152–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

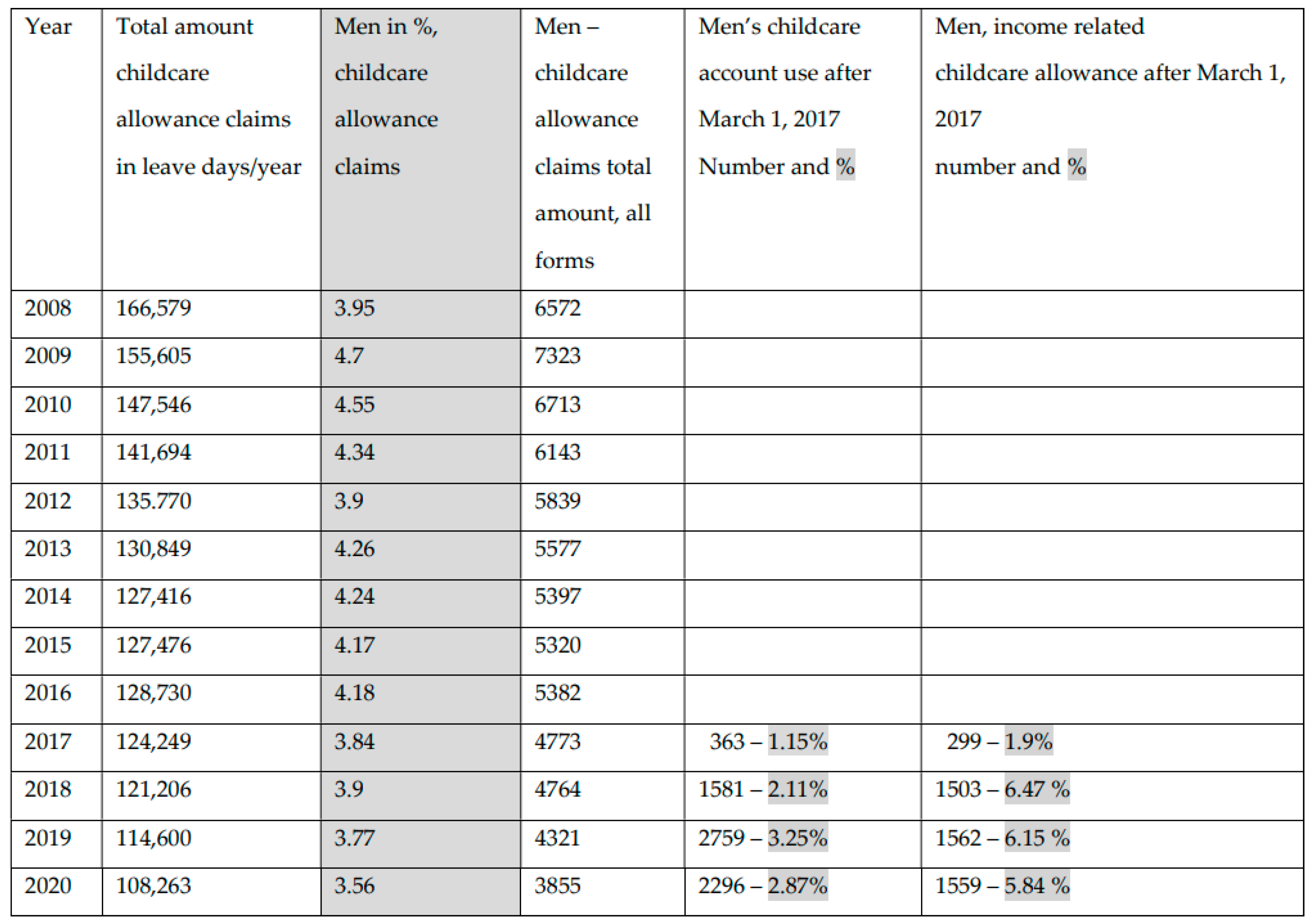

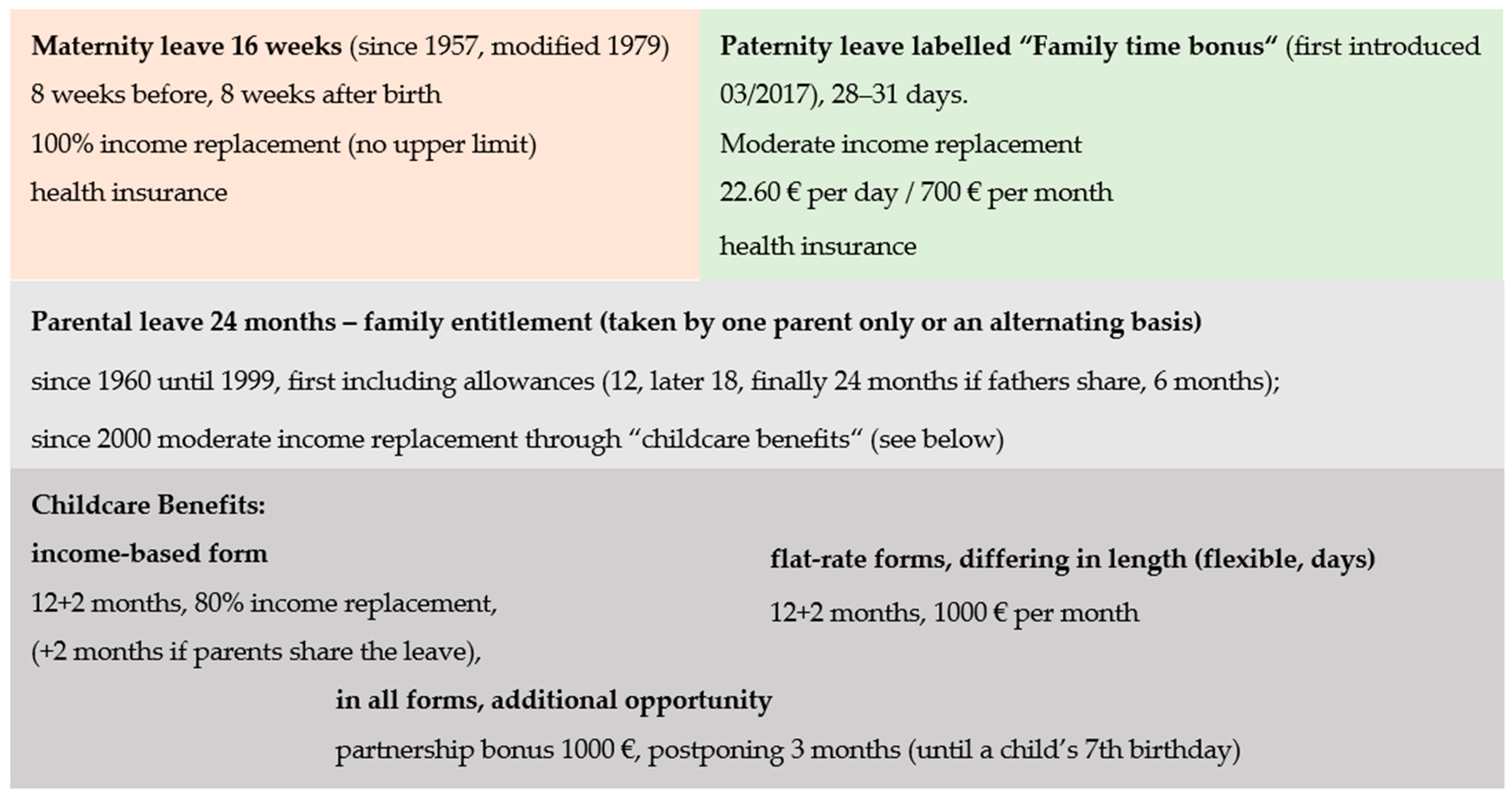

- Lorenz, Tina, and Georg Wernhart. 2022. Evaluierung des neuen Kinderbetreuungsgeldkontos und der Familienzeit: Quantitativer Teilbericht. Wien: ÖIF Forschungsbericht, Nr. 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lott, Yvonne, and Christina Klenner. 2018. Are the ideal worker and ideal parent norms about to change? The acceptance of part-time and parental leave at German workplaces. Community, Work & Family 21: 564–80. [Google Scholar]

- Mabaso, Bongekile P., Jaga Ameeta, and Doherty Tanya. 2022. Family supportive supervision in context: Supporting breastfeeding at work among teachers in South Africa. Community, Work & Family 26: 118–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaraggia, Sveva. 2013. Tensions between fatherhood and the social construction of masculinity in Italy. Current Sociology 61: 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaraggia, Sveva, Mauerer Gerlinde, and Schmidbaur Marianne. 2019. Feminist Perspectives on Teaching Masculinities: Learning Beyond Stereotypes. Teaching with Gender Series 15; London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marynissen, Leen, Wood Jonas, and Neels Karel. 2021. Mothers and Parental Leave in Belgium: Social Inequalities in Eligibility and Uptake. Social Inclusion 9: 325–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauerer, Gerlinde. 2018a. Both Parents Working: Challenges and Strains in Managing the Reconciliation of Career and Family Life in Dual-Career Families. Empirical Evidence from Austria. Social Sciences 7: 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauerer, Gerlinde. 2018b. Paternal Leave and Part-time work in Austria: Rearranging Family Life. In Fathers, Childcare and Work: Cultures, Practices and Policies. (Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research). Edited by Rosy Musumeci and Arianna Santero. Emerald Series; Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 12, pp. 183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Mauerer, Gerlinde. 2019. Decision-Making in a Poster Competition on Caring Fathers in Austria: Gender Theoretical Reflections on Prize-winning Posters and Media Images. In Feminist Perspectives on Teaching Masculinities: Learning Beyond Stereotypes, Teaching with Gender Series. Edited by Sveva Magaraggia, Gerlinde Mauerer and Marianne Schmidbaur. London and New York: Routledge, vol. 15, pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mauerer, Gerlinde. 2021. Work-Life-Balance und geschlechterspezifische Vorannahmen am Arbeitsplatz. Ergebnisse aus der empirischen Forschung zu Elternkarenzen in Österreich. SWS—Sozialwissenschaftlichen Rundschau 1: 43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mauerer, Gerlinde. 2022. Der Dual Career Mythos—Schlussfolgerungen aus empirischen Forschungen zu Väterkarenz und Elternteilzeitarbeit. In Gleichstellungspolitiken Revisted. Edited by Angela Wroblewski and Angelika Schmidt. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauerer, Gerlinde, and Eva-Maria Schmidt. 2019. Parents’ Strategies in Dealing with Constructions of Gendered Responsibilities at their Workplaces. Social Sciences 8: 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, Lindsey, Mathieu Sophie, and Doucet Andrea. 2016. Parental-leave rich and parental-leave poor: Inequality in Canadian labour market based leave policies. Journal of Industrial Relations 58: 543–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, Peter, Duvander Ann-Zofie, and Koslowski Alison, eds. 2019. Parental Leave and Beyond: Recent International Developments, Current Issues and Future Directions. Bristol: Bristol University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, Rosy, and Adrianna Santero. 2018. Fathers, Childcare and Work: Cultures, Practices and Policies. In Contemporary Perspectives in Family Research. Emerald Series; Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, vol. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Nakazato, Hideki. 2017. Fathers on Leave Alone in Japan: The Lived Experiences of Pioneers. In Fathers on Leave Alone: Work-Life Balance and Gender Equality in Comparative Perspectives. Edited by O’Brien Margaret and Karin Wall. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 231–56. [Google Scholar]

- Närvi, Johanna. 2012. Negotiating Care and Career within Institutional Constraints—Work Insecurity and Gendered Ideals of Parenthood in Finland. Community, Work & Family 4: 451–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nentwich, Julia C., and Elisabeth Kelan. 2014. Towards a Topology of ‘Doing Gender’: An Analysis of Empirical Research and its Challenges. Gender, Work & Organization 21: 121–34. [Google Scholar]

- Nentwich, Julia C., and Franziska Vogt. 2021. (Un)doing gender empirisch: Konzeptionelle, methodische und praktische Schlussfolgerungen. In (Un)doing Gender Empirisch. Edited by Julia C. Nentwich and Franziska Vogt. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyer, Gerda. 1997. Die Entwicklung des Mutterschutzes in der Schweiz, Deutschland und Österreich von 1877 bis 1945. In Frauen in der Geschichte des Rechts. Von der frühen Neuzeit bis zur Gegenwart. München: Beck, pp. 744–58. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Margaret, and Katherine Twamley. 2017. Fathers Taking Leave Alone in the UK—A Gift Exchange Between Mother and Father? In Comparative Perspectives on Work-Life Balance and Gender Equality. Life Course Research and Social Policies. Edited by Margaret O’Brien and Karin Wall. Cham: Springer, vol. 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Margaret, and Karin Wall. 2017. Fathers on Leave Alone: Work-life Balance and Gender Equality in Comparative Perspective. In Life Course Research and Social Policies 6. Cham: Springer Open. Available online: https://www.tinyurl.com/2fdykz25 (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- O’Brien, Margaret, Brandth Berit, and Kvande Elin. 2007. Fathers, Work and Family Life. Community, Work and Family 10: 375–86. [Google Scholar]

- Oláh, Livia Sz, Kotowska Irena, and Richter Rudolf. 2018. The New Roles of Men and Women and Implications for Families and Societies. Available online: https://familiesandsocieties.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/p_FamiliesAndSocieties/Olah_Kotowska_Richter_pdf (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Petts, Richard. 2022. Father Involvement and Gender Equality in the United States. Contemporary Norms and Barriers. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Petts, Richard J., Trenton D. Mize, and Kaufman Gayle. 2022. Organizational policies, workplace culture, and perceived job commitment of mothers and fathers who take parental leave. Social Science Research 103: 102651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riederer, Bernhard, and Caroline Berghammer. 2019. The Part-Time Revolution: Changes in the Parenthood Effect on Women’s Employment in Austria across the Birth Cohorts from 1940 to 1979. European Sociological Review 36: 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rille-Pfeiffer, Christiane, and Olaf Kapella. 2022. Evaluierung des neuen Kinderbetreuungsgeldkontos und der Familienzeit: Meta-Analyse. Wien: Universität Wien (ÖIF Forschungsbericht; Nr. 37). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Judy, Brady Michelle, Mara A. Yerkes, and Coles Laetitia. 2015. ‘Sometimes they just want to cry for their mum’: Couples’ negotiations and rationalisations of gendered divisions in infant care. Journal of Family Studies 21: 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardadvar, Karin. 2021a. Frauen fördern im Niedriglohnbereich—Befunde und Überlegungen aus der Reinigungsbranche. In Gleichstellungspolitiken Revisted. Edited by Angela Wroblewski and Angelika Schmidt. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 279–93. [Google Scholar]

- Sardadvar, Karin. 2021b. Regulierung von Fragmentierung—Die Gestaltung der Arbeitszeitform “geteilte Dienste” am Beispiel von Pflege, Reinigung und Gastgewerbe. In Arbeitszeit. Rahmenbedingungen—Ambivalenzen—Perspektiven. Edited by Martin Mülle and Charlotte Reiff. Wien: Verlag des ÖGB, pp. 239–59. [Google Scholar]

- Scambor, Elli, Jauk Dani, Gärtner Marc, and Bernacchi Erika. 2019. Caring Masculinities in Action: Teaching Beyond and Against the Gender-Segregated Labour Market. In Feminist Perspectives on Teaching Masculinities. Learning beyond Stereotypes. Edited by Sveva Magaraggia, Gerlinde Mauerer and Marianne Schmidbaur. London: Routledge, pp. 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Schieman, Scott, Philip J. Badawy, Melissa A. Milkie, and Bierman Alex. 2021. Work-Life Conflict during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Socius 7: 2378023120982856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Eva-Maria. 2018. Breadwinning as Care? The Meaning of Paid Work in Mothers’ and Fathers’ Constructions of Parenting. Community, Work & Family 4: 445–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, Eva-Maria. 2021. Flexible working for all? How collective constructions by Austrian employers and employees perpetuate gendered inequalities. Journal of Family Research 34: 615–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Eva-Maria, and Andrea E. Schmidt. 2022. Austria country note. In International Review of Leave Policies and Research 2020. Edited by Alison Koslowski, Sonja Blum, Ivana Dobrotić, Gayle Kaufman and Peter Moss. Hagen: Deposit_hagen–Fakultät für Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaften. Available online: https://www.leavenetwork.org/fileadmin/user_upload/k_leavenetwork/country_notes/2022/Austria2022.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Schmidt, Eva-Maria, Décieux Fabienne, Zartler Ulrike, and Schnor Christine. 2022. What makes a good mother? Two decades of research reflecting social norms of motherhood. Journal of Family Theory & Research 15: 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Eva-Maria, Zartler Ulrike, and Vogl Susanne. 2019. Swimming Against the Tide? Austrian Couples’ Non-normative Work-care Arrangements in a Traditional Environment. In New Parents in Europe: Couples in between Norms and Work-Care Practices. Edited by Daniela Grunow and Marie Evertsson. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd., pp. 108–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Austria. 2017. Registerbasierte Statistiken Haushalte und Familien Kalenderjahr 2017 Volkszählungen 1971–2001, Registerzählung 2011. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/fileadmin/publications/Registerbasierte_Statistiken_2017_-_Partnerschaften_-_Von_der_Homogamie_zur_Heterogamie_SB_10.33.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Statistics Austria. 2021a. Erwerbsbeteiligung (ILO) und wöchentliche Normalarbeitszeit der 15- bis 64-Jährigen nach Geschlecht, Familientyp und Alter des jüngsten Kindes, 2021. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/arbeitsmarkt/familie_und_arbeitsmarkt/080126.html (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Statistics Austria. 2021b. Kinderbetreuungsgeldbezieherinnen und -bezieher nach Geschlecht 2008 bis 2020. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/wirtschaft/oeffentliche_finanzen_und_steuern/steuerstatistiken/integrierte_lohn-und_einkommensteuerstatistik/index.html (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Strauss, Anselm. 1994. Grundlagen Qualitativer Sozialforschung. München: Fink. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research. Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tanquerel, Sabrina, and Marc Grau-Grau. 2020. Unmasking work-family balance barriers and strategies among working fathers in the workplace. Organization 27: 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, Robert. 2012. Informed grounded theory. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 56: 243–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronto, Joan B. 1993. Moral Boundaries. A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, Joan B. 2013. Caring Democracy. Markets, Equality, and Justice. New York and London: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Twamley, Katherine. 2019. Cold intimacies in parents’ negotiations of work-family practices and parental leave? The Sociological Review 67: 1137–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twamley, Katherine. 2021. ‘She has mellowed me into the idea of SPL’: Unpacking relational resources in UK couples’ discussions of Shared Parental Leave take-up. Families, Relationships and Societies 10: 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twamley, Katherine, Doucet Andrea, and Schmidt Eva-Maria. 2021. Introduction to special issue: Relationality in family and intimate practices. Families, Relationships and Societies 10: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verniers, Catherine, Virginie Bonnot, and Yvette Assilaméhou-Kunz. 2022. Intensive mothering and the perpetuation of gender inequality: Evidence from a mixed methods research. Acta Psychologica 227: 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walby, Sylvia. 2021. Developing the concept of society: Institutional domains, regimes of inequalities and complex systems in a global era. Current Sociology 69: 315–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Danielle, Anneka Janson, Michelle Nolan, Li Ming Wen, and Chris Rissel. 2011. Female employees’ perceptions of organisational support for breastfeeding at work: Findings from an Australian health service workplace. International Breastfeeding Journal 6: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesmann, Stephanie, Boeije Hennie, Anneke van Doorne-Huiskes, and Laura den Dulk. 2008. ‘Not worth mentioning’: The implicit and explicit nature of decision-making about the division of paid and domestic work. Community, Work & Family 11: 341–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzel, Andreas. 2000. Das problemzentrierte Interview. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung. No. 1. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1132/2519 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Wroblewski, Angela, and Angelika Schmidt. 2021. Gleichstellungspolitiken Revisted. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mauerer, G. Paid Parental Leave in Correlation with Changing Gender Role Attitudes. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090490

Mauerer G. Paid Parental Leave in Correlation with Changing Gender Role Attitudes. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(9):490. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090490

Chicago/Turabian StyleMauerer, Gerlinde. 2023. "Paid Parental Leave in Correlation with Changing Gender Role Attitudes" Social Sciences 12, no. 9: 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090490

APA StyleMauerer, G. (2023). Paid Parental Leave in Correlation with Changing Gender Role Attitudes. Social Sciences, 12(9), 490. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090490