A Scoping Review of Correctional-Based Interventions for Women Prisoners with Mental Health Problems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: women prisoners.

- Concept: correctional-based interventions using a randomized control trial (RCT). All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published between 2000 and 2023 were included.

- Context: addressing mental health problems.

- The studies selected included participants with mental health problems and took place at a women correctional facility or prison. Furthermore, articles that were in English, full-text, and accessible, as well as those describing any individual or group interventions conducted in prison settings for women prisoners with mental health problems were also included.

- The exclusion criteria were studies on male prisoner populations, interventions that did not address mental health problems, as well as pilot study, reviews, and documents.

2.3. Charting, Collecting, Summarizing, and Analyzing Data

3. Results

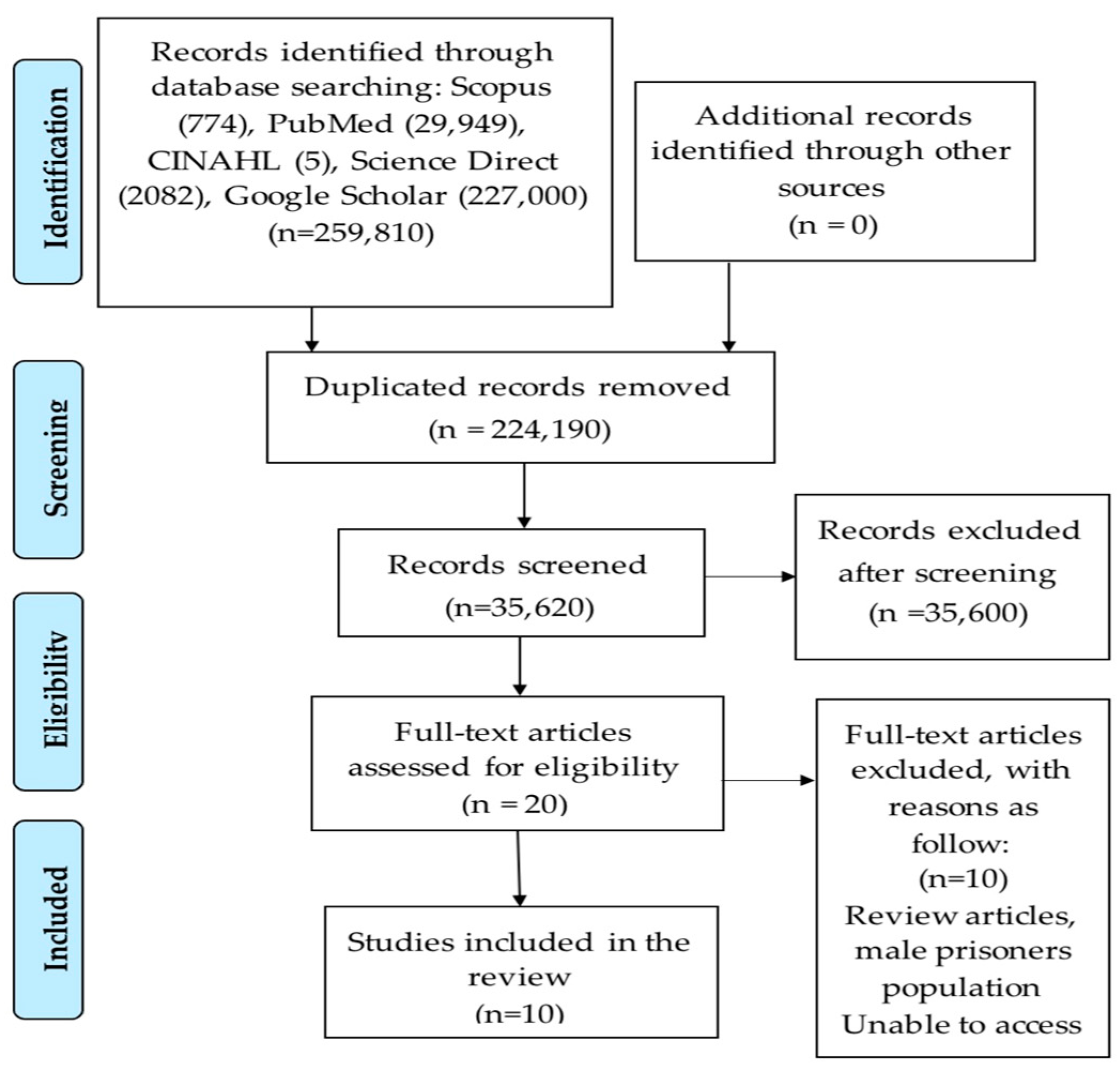

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Sample Characteristics

3.4. Types of Correctional-Based Interventions

3.4.1. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

3.4.2. Transcendental Meditation (TM)

3.4.3. Yoga

3.4.4. Seeking Safety (SS)

3.4.5. Transactional Analysis (TA) Training Program

3.4.6. Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy (TARGET) and Supportive Group Therapies

3.4.7. Gender-responsive Treatment (GRT)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antonetti, Giovanni, Daniela D’Angelo, Paola Scampati, Ileana Croci, Narciso Mostarda, Saverio Potenza, and Rosaria Alvaro. 2018. The Health Needs of Women Prisoners: An Italian Field Survey. Ann Ist Super Sanita 54: 96–103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arksey, Hillary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augsburger, Aurélie, Céline Neri, Patrick Bodenmann, Bruno Gravier, Véronique Jaquier, and Carole Clair. 2022. Assessing Incarcerated Women’s Physical and Mental Health Status and Needs in a Swiss Prison: A Cross-Sectional Study. Health & Justice 10: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Baranyi, Gergo, Megan Cassidy, Seena Fazel, Stefan Priebe, and Adrian P. Mundt. 2018. Prevalence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Prisoners. Epidemiologic Reviews 40: 134–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binswanger, Ingrid A., Joseph O. Merrill, Patrick M. Krueger, Mary C. White, Robert E. Booth, and Joann G. Elmore. 2010. Gender Differences in Chronic Medical, Psychiatric, and Substance-Dependence Disorders among Jail Inmates. American Journal of Public Health 100: 476–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, Laura S. 2016. Counterintuitive Findings from a Qualitative Study of Mental Health in English Women’s Prisons. International Journal of Prison Health 12: 216–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014. A Treatment Improvement Protocol: Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services; Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Churchill, Richard, Mandip Khaira, Virginia Gretton, Clair Chilvers, Michael Dewey, Connor Duggan, and Alan Lee. 2000. Treating Depression in General Practice: Factors Affecting Patients’ Treatment Preferences. British Journal of General Practice 50: 905–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ciucur, Daniel. 2013. A Transactional Analysis Group Psychotherapy Programme for Improving the Qualities and Abilities of Future Psychologists. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 78: 576–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Lisa A., Junius J. Gonzales, Joseph J. Gallo, Kathryn M. Rost, Lisa S. Meredith, Lisa V. Rubenstein, Nae- Yuh Wang, and Daniel E. Ford. 2003. The Acceptability of Treatment for Depression among African-American, Hispanic, and White Primary Care Patients. Medical Care 41: 479–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P. 2019. Targets and Outcomes of Psychotherapies for Mental Disorders: An Overview. World Psychiatry 18: 276–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Moor, Chealsea Alexandra. 2018. A Meta-Analysis of Substance Misuse Intervention Programs Offered to Women Offenders. Ottawa: Carleton University. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. 2020. Sharing the Vision: A Mental Health Policy for Everyone. Available online: http://www.Gov.Ie/En/Publication/2e46f-Sharing-The-Vision-A-Mental-Health-Policy-For-Everyone/ (accessed on 27 March 2023).

- Fazel, Seena, Adrian J. Hayes, Katrina Bartellas, Massimo Clerici, and Robert Trestman. 2016. Mental Health of Prisoners: Prevalence, Adverse Outcomes, and Interventions. Lancet Psychiatry 3: 871–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazel, Seena, and Katharina Seewald. 2012. Severe Mental Illness in 33,588 Prisoners Worldwide: Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry 200: 364–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feoh, Fepyani Thresna. 2020. Studi Fenomenologi: Stress Narapidana Perempuan Pelaku Human Trafficking. NURSING UPDATE: Jurnal Ilmiah Ilmu Keperawatan 11: 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ferszt, Ginette G., Robin J. Miller, Joyce E. Hickey, Fleet Maull, and Kate Crisp. 2015. The Impact of a Mindfulness Based Program on Perceived Stress, Anxiety, Depression and Sleep of Incarcerated Women. International Journal of Environmental and Research Public Health 12: 11594–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Julian D., Rocío Chang, Joan Levine, and Wanli Zhang. 2013. Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Affect Regulation and Supportive Group Therapies for Victimization-Related PTSD with Incarcerated Women. Behavior Therapy 44: 262–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannetion, Linthini, Janting Maria Magdalina Anak Dennis, Rosli Nur Deanna, R. Nurul Najwa Baharuddin, Saat Geshina Ayu Mat, Kamin Kamsiah, Othman Azizah, and Kamaluddin Mohammad Rahim. 2018. Psychotherapy for Prison Populations: A Review. ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry 19: 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gartlehner, Gerald, Patricia Thieda, Richard A. Hansen, Bradley N. Gaynes, Angela Deveaugh-Geiss, Erin E. Krebs, and Kathleen N. Lohr. 2008. Comparative Risk for Harms of Second Generation Antidepressants. Drug Safety 31: 851–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, Jane L., Thomas K. Houston, Benjamin W. van Voorhees, Daniel E. Ford, and Lisa A. Cooper. 2007. Ethnicity and Preferences for Depression Treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry 29: 182–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobeil, Renée, Kelley Blanchette, and Lynn Stewart. 2016. A Meta-Analytic Review of Correctional Interventions for Women Offenders: Gender-Neutral versus Gender-Informed Approaches. Criminal Justice and Behavior 43: 301–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Menéndez, Ana, Paula Fernández, Filomena Rodríguez, and Patricia Villagrá. 2014. Long-Term Outcomes of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Drug-Dependent Female Inmates: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 14: 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grella, Christine E., Katherine Lovinger, and Umme S. Warda. 2013. Relationships among trauma exposure, familial characteristics, and PTSD: A case-control study of women in prison and in the general population. Women & Criminal Justice 23: 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Leah A., and Sequoia N. J. Giordano. 2018. It’s Not Like Therapy: Patient-Inmate Perspectives on Jail Psychiatric Services. Adm Policy Ment Health 45: 265–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, Samantha, Gil Angela Dela Cruz, Natalie Kalb, Smita Vir Tyagi, Marc N. Potenza, Tony P. George, and David J. Castle. 2023. A Systematic Review of Gender-Responsive and Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Programs for Women with Co-Occurring Disorders. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 49: 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleher, Helen, and Rebecca Armstrong. 2005. Evidence-Based Mental Health Promotion Resource, Report for the Department of Human Services and Vichealth; Melbourne: Department of Human Services.

- Kessler, Ronald C., Amanda Sonnega, Evelyn Bromet, Michael Hughes, and Christopher B. Nelson. 1995. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives General Psychiatry 52: 1048–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodayarifard, Mohammad, Mohsen Shokoohi-Yekta, and Gregory E. Hamot. 2010. Effects of Individual and Group Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Male Prisoners in Iran. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 54: 743–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutz, Han, Jane Leserman, Claudia Dorrington, Catherine H. Morrison, Joan Z. Borysenko, and Herbert Benson. 1985. Meditation as an Adjunct to Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 43: 209–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, Patricia Villagrá, Paula Fernández Garcia, Filomena Rodríguez Lamelas, and Ana González-Menéndez. 2014. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy versus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorder with Incarcerated Women. Journal of Clinical Psychology 70: 644–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Catherine. 2006. Treating Incarcerated Women: Gender Matters. Psychiatric Clinics 29: 773–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebling, Alison, and Shadd Maruna. 2013. The Effects of Imprisonment. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Shannon M., April Fritch, and Nicole M. Heath. 2012. Looking Beneath the Surface: The Nature of Incarcerated Women’s Experiences of Interpersonal Violence, Treatment Needs, and Mental Health. Feminist Criminology 7: 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, Vivian W. M., and Calais K. Y. Chan. 2018. Effects of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and Positive Psychological Intervention (PPI) on Female Offenders with Psychological Distress in Hong Kong. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health 28: 158–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Yvonne, Andrew Day, and Sharon Casey. 2013. Understanding the Needs of Vulnerable Prisoners: The Role of Social and Emotional Wellbeing. International Journal of Prison Health 9: 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messina, Nena, Christine E. Grella, Jerry Cartier, and Stephanie Torres. 2010. A Randomized Experimental Study of Gender-Responsive Substance Abuse Treatment for Women in Prison. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 38: 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moloney, Katherine P., Brenda J. van den Bergh, and Lars F. Moller. 2009. Women in Prison: The Central Issues of Gender Characteristics and Trauma History. Public Health 123: 426–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muskett, Coral. 2014. Trauma-Informed Care in Inpatient Mental Health Settings: A Review of The Literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 23: 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najavits, Lisa. 2002. Seeking Safety: A Treatment Manual for PTSD and Substance Abuse. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Najavits, Lisa M. 2015. Trauma and Substance Abuse: A Clinician’s Guide to Treatment. In Evidence Based Treatments for Trauma-Related Psychological Disorders: A Practical Guide for Clinicians. Cham: Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature, pp. 317–30. [Google Scholar]

- Neacşu, Valentina. 2013. The Efficiency of a Cognitive-Behavioral Program in Diminishing the Intensity of Reactions to Stressful Events and Increasing Self-Esteem and Self-Efficiency in the Adult Population. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 78: 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidich, Sanford, Angela Seng, Blaze Compton, Tom O’Connor, John W. Salerno, and Randi Nidich. 2017. Transcendental Meditation and Reduced Trauma Symptoms in Female Inmates: A Randomized Controlled Study. Permanente Journal 21: 16-008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuytiens, An, and Jenneke Christiaens. 2016. Female Pathways to Crime and Prison: Challenging the (US) Gendered Pathways Perspective. European Journal of Criminology 13: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. 2018. Gender Specific Standards to Improve Health and Well-Being for Women in Prison in England. Available online: https://Assets.Publishing.Service.Gov.Uk/Government/Uploads/System/Uploads/Attachment_Data/File/687146/Gender_Specific_Standards_For_Women_In_Prison_To_Improve_Health_And_Wellbeing.Pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Ramanathan, Meena, Ananda Balayogi Bhavanani, and Madanmohan Trakroo. 2017. Effect of a 12-Week Yoga Therapy Program on Mental Health Status in Elderly Women Inmates of a Hospice. International Journal of Yoga 10: 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Rathod, Shanaya, Narsimha Pinninti, Muhammed Irfan, Paul Gorczynski, Pranay Rathod, Lina Gega, and Farooq Naeem. 2017. Mental Health Service Provision in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Health Service Insights 10: 1178632917694350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, Ingo, Annett Lotzin, Philipp Hiller, Susanne Sehner, Martin Driessen, Thomas Hillemacher, Martin Schäfer, Norbert Scherbaum, Barbara Schneider, and Johanna Grundmann. 2019. A Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial of Seeking Safety vs. Relapse Prevention Training for Women with Co-Occurring Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Substance Use Disorders. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 10: 1577092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segarahayu, Rizky Dianita. 2013. Pengaruh Manajemen Stres Terhadap Penurunan Tingkat Stres Pada Narapidana Wanita di Lapas Wanita Kelas IIA Malang. Malang: Universitas Negeri Malang. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Sanjay. 2012. Psychological Distress among Australians and Immigrants: Findings from the 2007 National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Advances in Mental Health 10: 106–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonin, Edo, William van Gordon, Karen Slade, and Mark D Griffiths. 2013. Mindfulness and Other Buddhist-Derived Interventions in Correctional Settings: A Systematic Review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 18: 365–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Murray B., John R. Walker, Andrea L. Hazen, and David R. Forde. 1997. Full and Partial Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Findings from a Community Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 154: 1114–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thekkumkara, Sreekanth Nair, Aarti Jagannathan, Krishna Prasad Muliyala, and Pratima Murthy. 2022. Psychosocial Interventions for Prisoners with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: A Systematic Review. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 44: 211–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkaman, Mahya, Jamileh Farokhzadian, Sakineh Miri, and Batool Pouraboli. 2020. The Effect of Transactional Analysis on the Self-Esteem of Imprisoned Women: A Clinical Trial. BMC Psychology 8: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, Stephen J., Annelise M. Mennicke, Susan A. Mccarter, and Katie Ropes. 2019. Evaluating Seeking Safety for Women in Prison: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Research On Social Work Practice 29: 281–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, Stephen J., Sarah E. Bledsoe, Johnny S. Kim, and Kimberly Bender. 2011. Effects of Correctional-Based Programs for Female Inmates: A Systematic Review. Research On Social Work Practice 21: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, Nichola, Helen L. Miles, Bessey Karadag, and Gemma Rogers. 2019. An Updated Picture of the Mental Health Needs of Male and Female Prisoners in the UK: Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Gender Differences. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 54: 1143–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2009. Women’s Health in Prison: Correcting Gender Inequity in Prison Health. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2012. United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-Custodial Measures for Women Offenders with Their Commentary: The Bangkok Rules. Geneva: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bergh J, Brenda, Emma Plugge, and Isabel Yordi Aguirre. 2014. Women’s Health and the Prison Setting. In Prisons and Health. Edited by Stefan Enggist, Lars Moller, Gauden Galea and Caroline Udesen. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- van den Bergh, Brenda J., Alex Gatherer, Andrew Fraser, and Lars Moller. 2011. Imprisonment and Women’s Health: Concerns about Gender Sensitivity, Human Rights and Public Health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 89: 689–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schaik, Digna J. F., Alexandra F. J. Klijn, Hein P. J. van Hout, Harm W. J. van Marwijk, Aartjan T. F. Beekman, Marten De Haan, and Richard van Dyck. 2004. Patients’ Preferences in the Treatment of Depressive Disorder in Primary Care. General Hospital Psychiatry 26: 184–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, Roy. 2017. World Female Imprisonment List: Women and Girls in Penal Institutions, Including Pre-Trial Detainees/Remand Prisoners. World Prison Brief. Available online: https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_female_prison_4th_edn_v4_web.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- White, Paul, and Harvey Whiteford. 2006. Prisons: Mental Health Institutions of the 21st Century? Medical Journal of Australia 185: 302–03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Brie, Cyrus Ahalt, and Robert Greifinger. 2014. The Older Prisoner and Complex Chronic Medical Care. In Prisons and Health. Edited by Stefan Enggist, Lars Moller, Gauden Galea and Caroline Udesen. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, Nancy, B Christopher Frueh, Jing Shi, and Brooke E. Schumann. 2012. Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Trauma Treatment for Incarcerated Women with Mental Illnesses and Substance Abuse Disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorder 26: 703–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, Emily M., Patricia van Voorhis, Emily J. Salisbury, and Ashley Bauman. 2012. Gender-Responsive Lessons Learned and Policy Implications for Women in Prison: A Review. Criminal Justice and Behavior 39: 1612–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnick, Caron, Jennifer Johnson, and Lisa M. Najavits. 2009. Randomized Controlled Pilot Study of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy in a Sample of Incarcerated Women with Substance Use Disorder and PTSD. Behavior Therapy 40: 325–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurhold, Heike, and Christian Haasen. 2005. Women in Prison: Responses of European Prison Systems to Problematic Drug Users. International Journal of Prisoner Health 1: 127–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Literature Search with Keywords | Database | Results |

|---|---|---|

| TITLE-ABS-KEY “inmates” OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “offenders” OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “prisoners” OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “convicts” AND TITLE-ABS-KEY “women” OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “female” AND TITLE-ABS-KEY “mental disorder” OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “mental health problems “ OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “Depression “ OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “schizophrenia “ OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “psychotic “ AND TITLE-ABS-KEY “correctional program” AND TITLE-ABS-KEY “interventions” AND TITLE-ABS-KEY “mental Health care” OR TITLE-ABS-KEY “mental Health services” | SCOPUS | 774 |

| ((mental Health care)) OR (mental Health services)) AND (correctional program)) AND (interventions)) AND (mental disorder)) OR (mental health problems)) OR (Depression)) OR (schizophrenia)) OR (psychotic)) AND (women)) OR (female) AND (inmates)) OR (offenders)) OR (prisoners) OR (convicts)) | PubMed | 29,949 |

| (inmates OR offenders OR prisoners OR convicts) AND (mental Health care OR mental Health services) AND (correctional program) AND (interventions) AND (mental disorder OR mental health problems) AND (women OR female) AND (inmates OR offenders OR prisoners OR convicts) | CINAHL | 5 |

| (mental Health care OR mental Health services) AND (correctional program) AND (interventions) AND (mental disorder OR mental health problems OR Depression OR schizophrenia OR psychotic) AND (women OR female) AND (inmates OR offenders OR prisoners OR convicts) | Science Direct | 2082 |

| (mental Health care OR mental Health services) AND (correctional program) AND (interventions) AND (mental disorder OR mental health problems OR Depression OR schizophrenia OR psychotic) AND (women OR female) AND (inmates OR offenders OR prisoners OR convicts) | Google Scholar | 227,000 |

| Authors, Country | Sample | Design | Intervention | Instruments | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ramanathan et al. 2017), India | 40 | RCT | Yoga | Hamilton anxiety scale, Hamilton rating scale for depression, Rosenberg self-esteem scale | Intragroup and intergroup comparisons of pre- and post-data revealed statistically significant (p < 0.001) changes in the scores, showing lower levels of depression and anxiety as well as an increase in self-esteem. |

| (Torkaman et al. 2020), Iran | 76 | RCT | TA training program | Demographic questionnaire, RSES | TA significantly increases the level of self-esteem (p = 0.001, t = 17.15). |

| (Wolff et al. 2012), USA | 209 | RCT | Seeking Safety | PCL, Global Severity Index, CAPS, SCID-NP, LSC-R, THQ, BSI, The End-of-Treatment Questionnaire | Seeking Safety was helpful in each of the following areas: overall, for traumatic stress symptoms, for substance use, to focus on safety, and to learn safe coping skills. |

| (Nidich et al. 2017), USA | 25 | RCT | Transcendental Meditation | PCL-C | Significant reductions were found in total trauma (p < 0.036), intrusive thoughts (p < 0.026), and hyperarousal (p < 0.043) on the PCL-C. Effect sizes ranged from 0.65 to 0.99 for all variables. |

| (Messina et al. 2010), USA | 115 | RCT | GRT | ASI, PDS | GRT participants had greater reductions in drug use. GRT participants reduced their drug use more, were more likely to stay in residential aftercare longer (2.6 months vs. 1.8 months, p < 0.05), and were less likely to be reincarcerated within 12 months of parole (31% vs. 45%, respectively; a 67% reduction in odds for the experimental group, p < 0.05). |

| (Zlotnick et al. 2009), USA | 49 | RCT | Seeking Safety | CAPS, TSC-40, THQ, SCID, ASI, TLFB, The Self-report Brief Symptom Inventory, Treatment Services Review, The Client Satisfaction Questionnaire, The End-of-Treatment Questionnaire, The Evaluation Treatment Interview, SS Adherence Scale |

Satisfaction with SS was high, and a greater number of SS sessions was associated with greater improvement on PTSD (F (1,22) = 5.51, p = 0.03), and drug use (F (1,22) = 6.58, p = 0.02). |

| (Tripodi et al. 2019), USA | 70 | RCT | Seeking Safety | CES-D, PCL-C | SS lowered depression scores and PTSD. |

| (Ford et al. 2013), USA | 80 | RCT | TARGET + Supportive Group Therapies | TESI, CAPS, ASSIST, CORE-OM, TSI, Generalized Expectancies for NMR, Hope Scale, Heartland Forgiveness Scale, ETO, WAI-B | Both interventions resulted in significant reductions in PTSD, and associated symptom severity, as well as an increase in self-efficacy. |

| (Lanza et al. 2014), Spain | 50 | RCT | ACT + CBT | ASI-6, MINI, Anxiety Sensitivity Index, AAQ-II, Multidrug Urinalysis, Self-recording | After 6 months, ACT showed a considerable improvement in lowering drug usage (43.8% in ACT vs. 26.7% in CBT). |

| (González-Menéndez et al. 2014), Spain | 37 | RCT | ACT + CBT | Ad hoc interview, ASI-6, Anxiety Sensitivity Index, AAQ-II, Multidrug Urinalysis, MINI | The mixed linear model studies revealed decreases in drug misuse, ASI levels, and avoidance repertoire in both situations, with no differences between groups. However, only ACT participants had lower rates of mental illness. At the 18-month follow-up, ACT outperformed CBT in terms of abstinence rates. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hidayati, N.O.; Suryani, S.; Rahayuwati, L.; Fitrasanti, B.I.; Ahmad, C.a. A Scoping Review of Correctional-Based Interventions for Women Prisoners with Mental Health Problems. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080452

Hidayati NO, Suryani S, Rahayuwati L, Fitrasanti BI, Ahmad Ca. A Scoping Review of Correctional-Based Interventions for Women Prisoners with Mental Health Problems. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(8):452. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080452

Chicago/Turabian StyleHidayati, Nur Oktavia, Suryani Suryani, Laili Rahayuwati, Berlian Isnia Fitrasanti, and Che an Ahmad. 2023. "A Scoping Review of Correctional-Based Interventions for Women Prisoners with Mental Health Problems" Social Sciences 12, no. 8: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080452

APA StyleHidayati, N. O., Suryani, S., Rahayuwati, L., Fitrasanti, B. I., & Ahmad, C. a. (2023). A Scoping Review of Correctional-Based Interventions for Women Prisoners with Mental Health Problems. Social Sciences, 12(8), 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080452