The Concept and Application of Social Capital in Health, Education and Employment: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

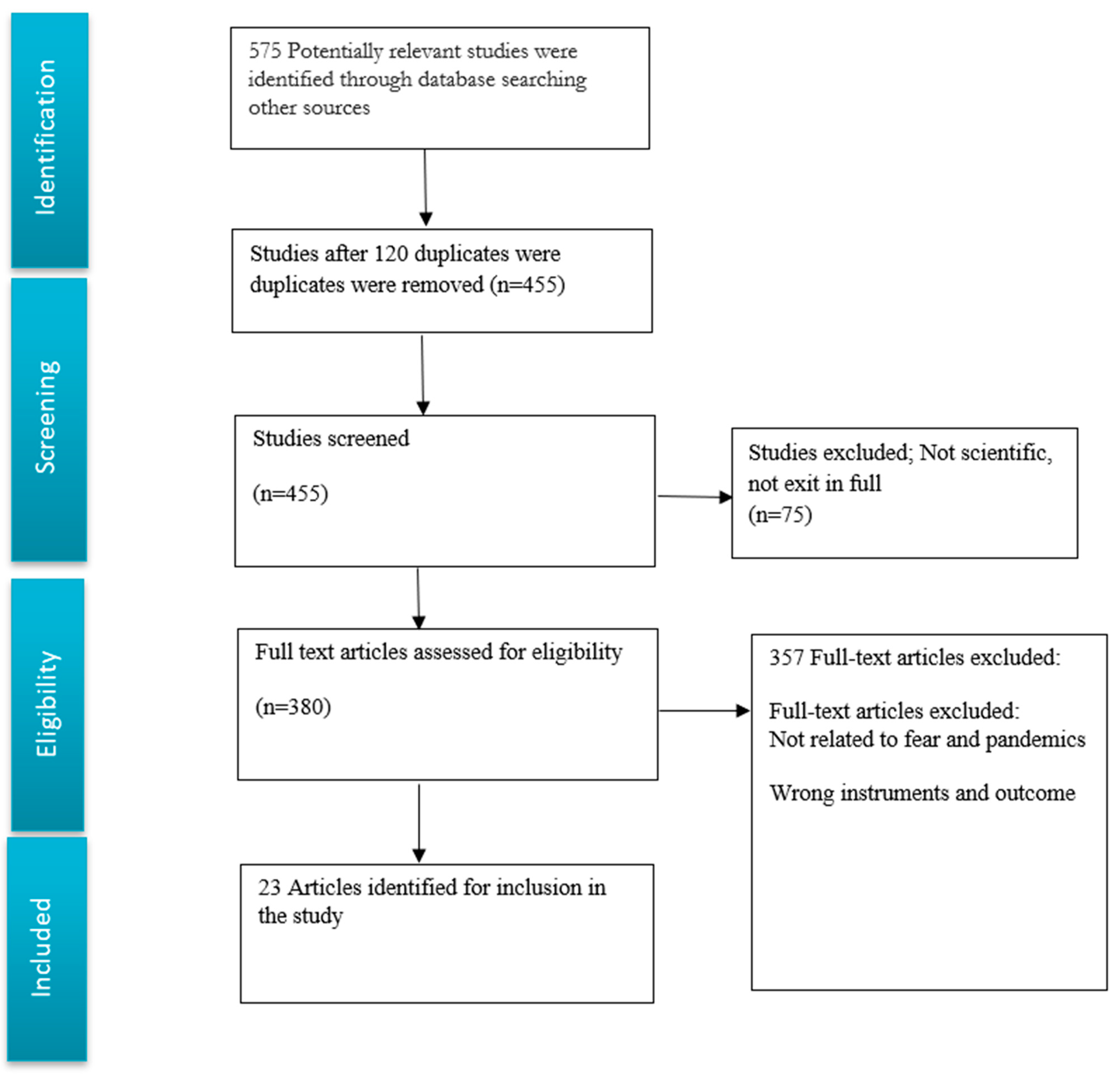

2. Method

2.1. Study Selection Strategy

2.2. Study Design Eligible; Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Quality of Assessment

2.4. Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.1.1. Location

3.1.2. Aims of the Studies and Areas

3.1.3. Nature of Study and Design

3.2. Findings

3.2.1. Social Capital and Health

3.2.2. Social Capital and Education

3.2.3. Social Capital and Employment

4. Discussion

4.1. Conceptualization of Social Capital in Health Education and Employment

4.2. Application of Social Capital in Health, Education, and Employment

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amaral, G., J. Bushee, Umberto Giuseppe Cordani, K. Kawashita, J. H. Reynolds, F. F. M. D. E. Almeida, F. F. M. de Almeida, Y. Hasui, B. B. de Brito Neves, R. A. Fuck, and et al. 2013. Defining Social capital. Journal of Petrology 369: 1689–99. [Google Scholar]

- Anakpo, Godfred, Syden Mishi, Nomonde Tshabalala, and Farai Borden Mushonga. 2023. Sustainability of Credit Union: A Systematic Review of Measurement and Determinants. Journal of African Business, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behtoui, Alireza. 2016. Beyond social ties: The impact of social capital on labour market outcomes for young Swedish people. Journal of Sociology 52: 711–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, Humnath, and Kumi Yasunobu. 2009. What is social capital? A comprehensive review of the concept. Asian Journal of Social Science 37: 480–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoli, Giuliano, and Nicolas Turtschi. 2015. Inequality in social capital and labour market re-entry among unemployed people. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 42: 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, Gerard. 2015. Network social capital and labour market outcomes: Evidence for Ireland. Economic and Social Review 46: 163–95. [Google Scholar]

- Brook, Keith. 2005. Labour market participation: The influence of social capital. Labour Market Trends 3: 113–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, Jasperina, Ellen Jansen, Andreas Flache, and Adriaan Hofman. 2016. The impact of social capital on self-efficacy and study success among first-year university students. Learning and Individual Differences 52: 109–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Catherine, Rachel Wood, and Moira Kelly. 1999. Social Capital and Health. London: Health Education Authority. [Google Scholar]

- CASP. 2019. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Cheung, Sin Yi, and Jenny Phillimore. 2014. Refugees, Social Capital, and Labour Market Integration in the UK. Sociology 48: 518–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Don, and Laurence Prusak. 2001. In Good Company. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, James S. 1988. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology 94: 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, James S. 1990. How worksite schools and other schools reforms can generate social capital: An interview with James Coleman. American Federation of Teachers 14: 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dika, Sandra L., and Kusum Singh. 2002. Applications of social capital in educational literature: A critical synthesis. Review of Educational Research 72: 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, Annahita, Hannah Sophie Klaas, Alexander Bastianen, and Dario Spini. 2019. Social capital and health: A systematic review of systematic reviews. SSM-Population Health 8: 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, Malin. 2011. Social capital and health--implications for health promotion. Global Health Action 4: 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlander, Sara. 2007. The importance of different forms of social capital for health. Acta Sociologica 50: 115–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, John. 2008. Social Capital. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, Francis. 2001. Social capital, civil society and development. Third World Quarterly 22: 7–20. Available online: http://fbemoodle.emu.edu.tr/pluginfile.php/38056/mod_resource/content/3/Socila%20capital_Fukuyama.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2011). [CrossRef]

- Harpham, Trudy, Emma Grant, and Elizabeth Thomas. 2002. Measuring social capital within health surveys: Key issues. Health Policy and Planning 17: 106–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawe, Penelope, and Alan Shiell. 2000. Social capital and health promotion: A review. Social Science and Medicine 51: 871–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, John F. 2007. Well-being and social capital: Does Suicide Pose a Puzzle? Social Indicators Research 81: 455–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helliwell, John F., and Robert D. Putnam. 2007. Education and social capital. Eastern Economic Journal 33: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imandoust, Sadegh Bafandeh. 2011. Relationship between Education and Social Capital. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 1: 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Kenneth, and Lars L. Andersen. 2018. Can high social capital at the workplace buffer against stress and musculoskeletal pain?: Cross-sectional study. Medicine 97: e0124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, Ichiro. 2006. Commentary: Social capital and health: Making the connections one step at a time. International Journal of Epidemiology 35: 989–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Tomoko, Ichiro Kawachi, Toshihide Iwase, Etsuji Suzuki, and Soshi Takao. 2013. Individual-level social capital and self-rated health in Japan: An application of the Resource Generator. Social Science & Medicine 1982: 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, Yan Kwan. 2014. Investigating the Relationship between Social Capital and Self-Rated Health in South Africa. Master’s thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, SA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lochner, Kimberly, Ichiro Kawachi, and Bruce P. Kennedy. 1999. Social capital: A guide to its measurement. Health Place 5: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, Jonathan. 1998. Social capital and health: Implications for public health and epidemiology. Social Science and Medicine 47: 1181–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomas, Jonathan. 2000. Essay: Using ‘Linkage And Exchange’To Move Research Into Policy At A Canadian Foundation: Encouraging partnerships between researchers and policymakers is the goal of a promising new Canadian initiative. Health Affairs 19: 236–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magson, Natasha R., Rhonda G. Craven, and Gawaian H. Bodkin-Andrews. 2014. Measuring Social Capital: The Development of the Social Capital and Cohesion Scale and the Associations between Social Capital and Mental Health. Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology 14: 202–16. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, Spencer, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2017. Twenty years of social capital and health research: A glossary. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 71: 513–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, Hiroshi, Yoshinori Fujiwara, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2012. Social capital and health: A review of prospective multilevel studies. Journal of Epidemiology 22: 179–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwogu, G. A., and I. E. Mmeka. 2015. Social Capital and Academic Achievement of Nigerian Youths in Urban Communities: A Narrative Perspective. Journal Of Educational Policy and Entrepreneurial Research 2: 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, Jessica, Ken Morrison, and Karen Hardee. 2014. Social capital to strengthen health policy and health systems. Health Policy and Planning 29: 1075–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguttu, James W., and Jabulani R. Ncayiyana. 2020. Social capital and self-rated health of residents of Gauteng province: Does area-level deprivation influence the relationship? SSM-Population Health 11: 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, Robert T., and Dina C. Maramba. 2015. The impact of social capital on the access, adjustment, and success of Southeast Asian American college students. Journal of College Student Development 56: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, Jennie, Helen Roberts, Amanda Sowden, Mark Petticrew, Lisa Arai, Mark Rodgers, Nicky Britten, Katrina Roen, and Steven Duffy. 2006. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version 1: b92. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Ramlagan, Shandir, Karl Peltzer, and Nancy Phaswana-Mafuya. 2013. Social capital and health among older adults in South Africa. BMC Geriatrics 13: 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, Justin, Anna V. Valuev, Yulin Hswen, and S. V. Subramanian. 2019. Social capital and physical health: An updated review of the literature for 2007–2018. Social Science & Medicine 236: 112360. [Google Scholar]

- Rydström, Ingela, Lotta Dalheim Englund, Lotta Dellve, and Linda Ahlstrom. 2017. Importance of social capital at the workplace for return to work among women with a history of long-term sick leave: A cohort study. BMC Nursing 16: 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, José P. 2013. The impact of social capital on the education of migrant children. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 42: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szreter, Simon, and Michael Woolcock. 2004. Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology 33: 650–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, Ester, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2015. The measurement of bridging social capital in population health research. Health Place 36: 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendy, Stone, Matthew Gray, and Jody Hughes. 2004. Social Capital at Work. The Economic and Labour Relations Review 14: 235–55. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, Rob, and Kwame McKenzie. 2005. Social capital and psychiatry: Review of the literature. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 13: 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, Winnie, Sankaran Venkata Subramanian, Andrew D. Mitchell, Dominic T. S. Lee, Jian Wang, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2007. Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China. Social Science and Medicine 64: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors | Study | Countries Covered | Estimation Method(s) | Conceptualization/Operationalization of Social Capital | Summary of Findings on Social Capital Applications/Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Campbell et al. 1999) | Social capital and health | UK | Systematic analysis | Social capital was conceptualized or operationalized in terms of a number of characteristics such as community networks, networking, civic engagement, civic identity, reciprocity, trust. | This paper conceptualized social capital as interactions between people through systems that enhance and support that interaction. The study identified that a bulk of studies investigate the macro socioeconomic factors and a gap in analysis of the community level relationships and networks. This has involved a move away from persuading individuals to change their behaviour through the provision of information about health risks, towards an interest in creating community contexts that are most likely to enable health-promoting behaviours to occur. |

| (Ehsan et al. 2019) | Social capital and health | General coverage | Systematic analysis | Indicators were used along with approaches such as the Cohesion approach (indicators for family cohesion: collective efficacy, informal control, social interaction, sense of belonging). Cognitive indicators such as trust, social cohesion, perceived social support, sense of community. Network approach (indicators for family support: emotional support, instrumental support, family conflict; family network: network structure, quality of family ties). | The study found that there is a good amount of evidence to indicate that social capital is associated with better health, though one review found a negative relationship (behavioural contagion). They added that the interactions between the multi-dimensionality of social capital, dynamics between actors, time, contexts, and underlying psychological mechanisms are useful to consider in the relationship between social capital and health |

| (Eriksson 2011) | Social Capital and health implications for health promotion | Sweden | Systematic analysis | Social capital was conceptualized as social networks, norms, solidarity, and reciprocity. | Social capital as an individual characteristic adds to new knowledge on how social capital intervention programs can be designed to meet target groups. The classification of social capital into bonding, bridging, and linking can be useful for mapping social capital in terms of which ones are available and which ones are health enhancing and damaging. In health promotion programs, it is important for social capital to be characterized as a community phenomenon. |

| (Harpham et al. 2002) | Measuring social capital and health | Systematic analysis | Structural (connectedness), cognitive (reciprocity, sharing, and trust. | The studies found that the use of surveys that are not originally designed to measure social capital provide conflicting results. The study also concluded that social capital and social support influenced health, and reported stress and health behaviour differently depending on how they are measured. The study identified the need for tailor-made surveys that include reliability and validity in their measures. | |

| (Hawe and Shiell 2000) | Social capital and health promotion | Canada | Systematic analysis | Microlevel conceptualization (community ties) and macro level (state–society connection). | The study concluded that income inequality leads to poor health outcomes and a disfranchised social capital. The study identified that communities with high levels of inequality have poor health outcomes. They suggest that, although the relational properties of social capital are important (e.g., trust, networks), the political aspects of social capital are perhaps under-recognized. |

| (Lau 2014) | Investigating the relationship between social capital and self-rated health in South Africa | South Africa | Mixed methods | Personalized trust, generalized trust, reciprocity, and associational activity. Group participation. | The study identified that individualized trust, individualized community service membership and neighbourhood personalized trust as beneficial to self-rated health |

| (Lomas 1998) | Social capital and health: implications for public health and epidemiology | Canada | Systematic analysis | Social system comprising interlink of physical structure, social structure, and social cohesion. | The study emphasized the need for the retooling of social capital measurement to ensure relevance to the health sector. |

| (Murayama et al. 2012) | Social Capital and Health: A Review of Prospective Multilevel Studies | Japan | Systematic analysis—13 articles | Social trust and civic participation at individual level and area level (family cohesion). Social cohesiveness and trust at state level. Cognitive and structural components of workplace social capital (sense of cohesion, mutual acceptance, trust for the supervisor). | The study identified that social capital has a positive impact on health regardless of study design, setting follow-up periods for type of health outcome. Prospective studies were conducted in Western countries whilst cross-country studies were undertaken in Asian countries. |

| (Ferlander 2007) | Importance of different forms of social capital for health | Sweden | Systematic analysis | Social capital indicators were of two categories: (1) Horizontal ties (social networks), voluntary associations, family, relatives, friends, and colleagues; (2) Vertical ties (work hierarchies and criminal networks, clan relations, network ties between citizens and street gangs, civil servants. | More research needs to be conducted into the different forms of social capital and their effects on health. A special focus should be placed on the health impacts of cross-cutting—or bridging and linking—forms of social capital. |

| (Ramlagan et al. 2013) | Social capital and health among older Adults in South Africa | South Africa | Cross sectional study Multilevel logistic | Social capital was assessed with six components: being married or cohabiting, social action, sociability, trust and solidarity, safety, and civic engagement. | The study reported that, in South Africa, cognitive physical activity and self-rated health dropped as age progresses. Those with higher educational level have high cognitive functioning and good health. However, for the physically inactive, this remained low despite educational level. Older people reported low social capital in terms of sociability and social action whilst they have social capital in trust and solidarity. |

| (Yip et al. 2007) | Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China | Rural China | Multi-level logistic linear model | Social capital was measured using the ‘‘structural/cognitive form (structural dimension encompasses behavioural manifestations of social capital, namely participation in formal associations). The ‘‘cognitive’’ dimension subsumes attitudinal manifestations, such as trust in others and reciprocity between individuals. | The study found that there is a positive relationship between social capital and all the three measures of health. The study further found that trust affects health and wellbeing through pathways of social network and support. |

| Author | Study | Countries Covered | Estimation Method(s) | Conceptualization/Operationalization of Social Capital | Summary of Findings on Social Capital Applications/Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Brouwer et al. 2016) | Impact of social capital on self-efficacy and study amongst first year students | Netherlands | Bivariate correlation analysis | Indicators of social capital were categorized as follows: family capital (family connection), faculty capital (academic and mentorship support), peer capital (support from friends and colleagues). | The study found that the returns from casual capital are less than those from peer capital, whilst faculty capital provides the highest returns of social capital towards educational success and advice. The study also found a positive relationship between variables of social capital and students’ self-efficacy. |

| (Dika and Singh 2002) | Application of social capital and education | Systematic analysis | Family (family cohesion, support), community (society, religious involvement) and social support system. | The study traced the conceptualization of the idea of positivity between education and social capital. Nearly all these studies focus on the conceptualization of social capital as norms rather than access to institutional resources. This is because of the poor theoretical outline in Coleman’s concepts. | |

| (Helliwell and Putnam 2007) | Education and social capital | USA | Quantitative research | Trust and social engagement. | They found that relative education has an impact on trust and social enjoyment. The study suggests that education increases social trust. The study argues that engagement widens the level of education; however, the US empirical study does not conform to this proposition. |

| (Imandoust 2011) | Relationship between education and social capital | Iran | Systematic analysis | Connections within and between social networks. | The study identified social capital as a lubricating factor between education and economic development and recognizes that distance learning has an impact on the development of social capital and there is a need for the development of mechanisms that enhance social capital in distance learning. |

| (Palmer and Maramba 2015) | Impact of social capital on the access, adjustment and successor Southeast Asian American College students | USA | Qualitative approach Epistemological approach anchored on constructivist | Social capital includes caring agents, support services, organizations facilitated. | The study identified that, for academic success, the students were more heavily dependent on the network support services of the organizations than on their caring agents. The study explained the cause of the phenomenon to be the lack of experience in higher education of the caring agents, thus causing them to be a poor source of returns. |

| (Salinas 2013) | Impact of social capital on the education of immigrant students | USA | Qualitative research approach | Family ties and family culture. | The findings illustrate how social capital was beneficial for student performance in and out of the classroom through intersecting themes and patterns, which included feminism and compadrazgo. Culturally based recommendations for school leaders and community organizations are presented. |

| Authors | Study | Countries Covered | Years Covered | Estimation Method(s) | Conceptualization/Operationalization of Social Capital | Summary of Findings on Social Capital Applications/Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Behtoui 2016) | Beyond social ties: the impact of social capital on labour market outcome for young Swedish people | Swiss | 2015 | Weighted least squares | Social capital as individuals’ resources which are accessible through social networks (social capital). | The results indicate that the use of social networks is a source of finding work in Sweden; however, it does not offer an advantage in competition for better jobs. |

| (Bonoli and Turtschi 2015) | Inequality in social capital and labour market re-entry among unemployed people | Swiss | 2015 | OLS | Value of someone’s network, which in turn depends on the number of relations someone has and on their position in the social structure. | The study found that immigrants have more work-related social capital when measured in number of workmates, which translates to earlier exit from unemployment than Swiss people; however, in the Swiss it has failed to translate into a better quality job. |

| (Brady 2015) | Network social capital and labour market | Ireland | 2015 | Probit models | Social networks (how frequently contacts are made with friends, relatives, and a range of organisations). | The study found that a person’s weak ties contribute more to their employment whereas their strong ties, for example to family, have a weak impact on employment. |

| (Brook 2005) | Labour Market participation: the influence of social capital | UK | 2015 | Systematic analysis | Networks of contacts or information. | Social capital can provide positive networks of contacts or information, assisting in successful job searches for people seeking employment, and also helps those in employment in terms of progression within the workplace. The study also reports that social capital can be a negative characteristic and may disadvantage some groups within society in general or individuals within an organization. |

| (Cheung and Phillimore 2014) | Refugees, social capital and labour market integration | UK | 2014 | Multinomial logit models | Social capital was measured as social networks identified as (1) friends, (2) relatives, and (3) national or ethnic community, religious groups, and other groups and organizations. | The results indicated that the breadth of networks of refugees is highly dependent on the language barriers and the time period in the UK. The results also show that the existence of a network does not make a significant contribution towards integration into employment. The study recognizes that mere social capital has no significant benefit in the UK, but rather pre-immigration qualifications, time in the UK, and pre-employment quality have a significant impact. |

| (Wendy et al. 2004) | Social capital at work | Australia | 2002 | Qualitative | Social capital was conceptualized as relationships and networks with individuals, groups, and organizations (bonding, bridging and linking). | There is a positive relationship between social capital and labour in Australia. The informally emphasized social capital individuals are more likely to be employees and to achieve full-time employment than other groups. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mishi, S.; Sibanda, K.; Anakpo, G. The Concept and Application of Social Capital in Health, Education and Employment: A Scoping Review. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080450

Mishi S, Sibanda K, Anakpo G. The Concept and Application of Social Capital in Health, Education and Employment: A Scoping Review. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(8):450. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080450

Chicago/Turabian StyleMishi, Syden, Kin Sibanda, and Godfred Anakpo. 2023. "The Concept and Application of Social Capital in Health, Education and Employment: A Scoping Review" Social Sciences 12, no. 8: 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080450

APA StyleMishi, S., Sibanda, K., & Anakpo, G. (2023). The Concept and Application of Social Capital in Health, Education and Employment: A Scoping Review. Social Sciences, 12(8), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12080450