Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic drew public attention to the essential work and vulnerability of low-income Latina immigrants. Less recognized were the ways immigrant community organizations mobilized under exceptional conditions to provide immediate support to their communities while continuing to work toward durable systematic change. This paper analyzes the approach of Mujeres Unidas y Activas (MUA) in the San Francisco Bay Area. Over three decades, MUA developed an organizing model that builds transformative relationships among peers and provides direct services and leadership development for civic engagement. MUA has a long history of research collaborations and self-study aligned with critical community-engaged research methods and values. In 2019, MUA formed a research team of its leaders and academics to analyze the impact of their model. Since data collection occurred between March 2020 and December 2022, the research also documented the organization’s response to COVID-19. This paper argues that specific organizational values and practices of liderazgo, apoyo, and confianza (leadership, support, and trust) proved to be particularly powerful resources for sustaining individuals and community work through the pandemic, enabling women who have experienced multiple forms of structural violence to perceive themselves as capable of healing themselves and their communities while working to address root causes of trauma and inequity.

Keywords:

community organization; COVID-19; health equity; immigrant rights; Latinas; violence; healing 1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic provided ample evidence on how pre-existing structural inequities manifest starkly in human terms in times of crisis. It also offered powerful examples of strengths and limitations of grassroot organizations working to address immediate needs and root causes of disparities in their communities (Cohen et al. 2022). The full extent of the COVID-19 pandemic’s repercussions on the over 62 million Latino/a/x/e people in the U.S.1 remain to be observed. Latinos were disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, with early national mortality rates among immigrants being 8.7 times higher than those in US born non-Hispanic whites aged 18 to 54 (Garcia et al. 2021). In the San Francisco Bay Area, Latino/a/x/e people contracted COVID-19 at more than three times the rate compared to non-Hispanic whites and were at far greater risk of dying from COVID-19 (Fimrite 2020). In addition to being disproportionately represented in essential services that required continued employment (Chamie et al. 2021), often with limited workplace protections from infection, immigrant and mixed-status Latino families faced legal exclusion from federal relief programs and fear of immigrant enforcement, resulting in extremely unmet basic needs (Bernstein et al. 2020).

Despite facing their own financial and workforce struggles due to the pandemic, community-based organizations serving and staffed by Latina/o/x/e people played critical roles in addressing community needs through their role as trusted sources of information, advocacy, and material support for community members, including being mediating partners for government relief and public health institutions (Bibbins-Domingo et al. 2021; Cohen et al. 2022). The remarkable impact of intersectional feminist and women’s rights organizations paired with direct services and mutual aid provision during the pandemic has been documented among small- and medium-sized local organizations around the world (Tabbush and Friedman 2020; UN Women 2021).

In this paper, we analyze the practices of an organization led by and for Latina immigrants, and their work to address both immediate community needs as well as the structural inequities undergirding the pandemic’s disparate impacts. We argue that relational organizational practices that provided both emotional and instrumental support as well as civic engagement and leadership development proved to be crucial to their effective work during the pandemic period. Political organizations that was trauma-informed and grassroot-led aided in individual healing, strengthened healthy community relationships, and sustained their work to transform institutions and dominant cultural practices that harm not only Latina immigrants but also other marginalized groups.

Mujeres Unidas y Activas (MUA)2 was founded and continues to be led by low-income, primarily Spanish-speaking3, immigrant women from Mexico and Central America who reside in the San Francisco Bay Area. At the start of the pandemic, in early 2020, MUA was just initiating a retrospective community-engaged research project focused on the development of its organizing model, its impact on members, local community life, and public policy over its thirty-year history. While the study began before the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, the context demanded attention and framed the collective, collaborative processes of inquiry and analysis that produced this paper. We found several key aspects of MUA’s organizational culture and practices were critical resources to the group, its members, and the broader community of Latina immigrants as they struggled to survive and move forward through the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this paper, we offer a brief history of MUA, including its collective response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the origins and methods of this collaborative project, and analyze specific values and activities that enabled the organization, staff, and members to not just survive but advance in their advocacy work during the first years of this pandemic. MUA’s attention to learning (aprendizaje), including internal training, assessment, and collaborative analysis, provided a foundation for the research team’s work that was specific to MUA’s organizational culture, while aligning with contemporary academic formulations of Critical Community Based Research as both epistemology and social justice practice (Fine and Torre 2019; Gordon da Cruz 2017). In addition to methodological lessons learned, we share key findings that MUA’s core historical practices are based on support (apoyo), trust (confianza), and leadership (liderazgo) and were critical resources that were also restored and adapted in important ways during the COVID-19 pandemic. These core practices enabled the organization to respond effectively to unprecedented challenges facing its members and their communities. Furthermore, MUA’s understanding of aprendizaje informed the way MUA members and academic allies learned to work together while carrying out the project, building research skills and capacity that centered community expertise and epistemologies in service to their work for social justice.

2. Background and Literature

The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn attention to the importance of addressing social determinants of health (e.g., housing, healthcare, education, occupation, and language access) among immigrant communities in the U.S. Immigration, including the historical and global geopolitical forces driving it, is itself a key social determinant of health that “poses challenges to conventional understandings and practices because it requires going beyond the hold of individualism and behaviorism in public health and instead requires tackling a wider sphere of upstream structural factors affecting health” (Castañeda et al. 2015, p. 386). Centering immigration as a social determinant of health provides attention to individual and collective experiences of health and health care and also the social, economic, and political structures framing them, including racism (Viruell-Fuentes et al. 2012) and immigrants’ own agency, activism, and advocacy (Chávez et al. 2007; Chun et al. 2013). Organizations led by low-income Latina immigrants have critical expertise in analyzing and addressing the conjuncture of legal, economic, gender, and racial structures framing the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their own people. In the case of MUA, leaders, staff, and members all faced major changes in daily practices to accommodate the shelter-in-place orders that took effect in the region on 17 March 2020.

Studies of immigrant community-based organizations have documented their roles facilitating “immigrant integration,” from economic and political participation to accessing key social services from education to health care (Chun et al. 2013; De Graauw 2016; Delgado-Gaitán 2001; Dixon et al. 2018; Ramakrishnan and Bloemraad 2008). Critical community-based research in psychology has documented an association between activism and improved health among social groups facing multiple lines of structural oppression (Frost et al. 2019). Studies of community-based immigrant rights groups suggest that organizing themselves can positively impact immigrant health and well-being (Bloemraad and Terriquez 2016) while building community power to make claims on state and local governments that mitigate the impact of race and class disparities on health (Chávez et al. 2007; Minkler and Wallerstein 2012).

While the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is still unknown, this case offers important insights into the potential of transformative political work led by low-socioeconomic position (SEP) immigrant women of color to address immediate community needs in a time of crisis that also accounts for root causes of social disparities along the lines of race/ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, and national origin. Our findings add further evidence that- small and medium-sized local–regional organizations like MUA that employ intersectional feminist models of grassroot leadership are critical resources for service providers, policy makers, and community-engaged scholar-educators. Such organizations are positioned to help advance “just recovery” efforts that can address immediate needs while transforming structures of inequality. They warrant not only increased attention but also sustained support for their core operations and organizing activities both in the U.S. and internationally (UN Women 2021).

3. Methods

Social scientists influenced by feminist, queer, indigenous, Black, anti-racist, and decolonial theory and activism have advocated for critical community-engaged research and scholarship that both advances social justice projects defined by impacted communities and challenges traditional power relations in academic research (Fine and Torre 2019). Such projects aim to address root causes of social and structural inequities through research collaborations that also address the need for healing between universities and non-academic communities (Gordon da Cruz 2017). Less attention has been given to the methodological and epistemological contributions of community-based inquiry and reflection in which articulated contributions to the academic literature take a back seat to social and political priorities and goals.

MUA has a long history of successful research collaborations and of integrating research into their organizing work. The group was founded by eight immigrant women who met in the course of a community-based research project, a needs assessment conducted by two graduate students in social work and two immigrant women community members in the San Francisco Bay Area (Hogeland and Rosen 1990). In the three decades since its founding, the organization grew from eight founding members to over 800 active members4, over 30 staff members, and two offices in San Francisco and Oakland, as well as a burgeoning program site in Union City, MUA developed practices that prioritized skills and leadership development of its membership and staff in support of robust participation in and outside of the organization. While not framed internally as “research,” at least prior to this project, these practices include internal documentation, training, and assessment using both quantitative and qualitative measures, and collective processes of analysis of internal and external conditions to guide programs, campaigns, and organizational planning.

Past MUA collaborations have produced white papers and reports for practitioners as well as academic theses, articles, and books on overcoming domestic violence and barriers to services for survivors (Hogeland and Rosen 1990; Jang et al. 1990, 1997; Goldfarb and Wadhwani 1999), transforming political and personal subjectivity (Ochoa Camacho 2006; Coll 2010), popular education (Graves 2005), and organizing domestic workers (Ito et al. 2014; Mitchell and Coll 2017; Tudela Vásquez 2016). MUA has directed its own studies examining the internal processes by which it had evolved from a member-based organization to a member-led organization (Regan et al. 2018) and contributed to both the development and documentation of the transformational leadership program (Ito et al. 2014) and history curriculum on the domestic workers movement (Guglielmo and Joffroy 2020).

MUA’s tradition of knowledge production through documentation, reflection, and analysis reflects a core value and commitment to individual and collective learning referred to as aprendizaje. In a context in which most members have had limited and often negative experiences of formal education, aprendizaje challenges deficit formulations of their educational levels and “non-English speaking” status, even as MUA helps women develop the language and literacy skills they may seek. Aprendizaje learning is a collective, life-long process to which women contribute as holders and builders of knowledge. This research project offered the opportunity to develop individual and organizational research capacity, demystifying research through the practical work of designing and implementing the research, including training in academic research methods and terminology. The process of implementing the project was as much a learning opportunity as the results of the organization’s unique approach to building community power.

In early 2020, prior to the start of shelter-in-place, MUA formed a research team made of ten MUA staff members representing the different program areas and leadership5 and an academic team of three that later expanded with the addition of, over time, five graduate student research assistants6. While many collaborative research projects originate with academics or academic institutions, MUA initiated the development of proposals for support of this project and sought out academic partners willing to work collaboratively as co-investigators, rather than the other way around. The team’s work began remotely and online by articulating goals and guiding values for their work together. Bimonthly team meetings featuring introductory method training in qualitative and quantitative research and ethics so that all team members could participate in design, data collection, and research analysis. In 2020 and 2021, subcommittees of the team supported developing survey instruments and interview guides, identified sampling goals and priorities, conducted outreach and recruitment of participants, analyzed preliminary results and findings for discussion by the full research team, and identified further lines of inquiry. The team conducted over 200 surveys, 40 interviews, and seven focus groups (~60 participants), with members, staff, former staff, colleagues in immigrant rights and women’s organizations, and adult children of staff and members. Research team members also conducted participant-observations and observations of organizational activities.7 All team meetings and materials were in Spanish and reports were developed and discussed together in Spanish first, including this article. Community dissemination similarly takes the form of Spanish language training materials, workshops, and presentations by MUA researcher team members, including in academic settings using interpretation, and short educational videos shared online and in staff, member, and board retreats.

The original scope of research expanded to include MUA’s adaptation to the pandemic. As the organization shifted to fully remote recruitment and programming, training, development of research instruments, data collection, and analysis meetings occurred entirely online. As member-leaders and staff were integrating electronic platforms and social media into their organizational and peer support work, so did the research team. An unexpected benefit of the research project was that it provided participants an opportunity outside their primary areas of program and organizing work. Research team meetings offered MUA staff members an opportunity to share in real-time their reflections and observations about not only community conditions but also their own pandemic-related work and personal struggles. The research project itself became an additional site for peer support, aprendizaje, and collective analysis that proved to be healing as well as intellectually engaging for MUA members. As a result, research team attendance and participation was consistent and enthusiastic in spite of the additional burdens of labor and personal loss that staff members carried during the pandemic.

4. Findings: Core Organizational Values and Practices

MUA’s guiding principles and practices are grounded in its dual mission of promoting individual personal transformations of women and building collective community power for social and economic justice. MUA’s early accomplishments in the 1990s included defending access to prenatal care for all women, including those without legal immigration status, and protecting immigrant domestic violence survivors in federal Violence Against Women legislation (VAWA). Since 2005, MUA’s leadership in the domestic worker and immigrant rights movements has resulted in increased legal protections for domestic workers at local, state, federal, and international levels.

MUA is an identity-based organization open to anyone who identifies as a Latina immigrant woman. Since MUA provides trauma-informed services, it attracts women who are survivors of violence. Over 80% of MUA members are survivors of domestic violence, and at least 43% are survivors of sexual assault. Most have lived in the US for ten years or more. MUA focuses on helping women transform both violent relationships in their home lives and also structural relationships of economic and sexual violence at work. Approximately 85% of members reported working as domestic workers outside the home in surveys conducted before (2018) and during (2021) the pandemic. While most MUA members are from Mexico, approximately one-third are from Central America (with more from El Salvador and Guatemala, and fewer from Honduras and Nicaragua). Over 90% communicate primarily in Spanish but a growing number identify as Mam, the indigenous people of Guatemala, and speak primarily Mam or are bilingual in Mam and Spanish. Ninety percent of members have at least one child, and over half are single or divorced.

MUA confronted the pandemic supported by the human, cultural, and political resources that are the legacy of its history. Principal among these is the understanding embedded in MUA’s dual mission of the dynamic and interdependent relationship between immigrant women’s need for individual material and social support to survive and thrive in the US, and the larger structures of inequality and injustice that frame individual and collective experiences. Guided by its dual mission (peer support for personal transformation and civic–political participation) and core values (compassion, respect, mutual support, self-determination, learning, solidarity, and transparency), MUA cared for its staff, members, and broader community during the pandemic using every resource from the group’s history, relationships, and experience.

MUA members’ experience with policies of exclusion and neglect by the state, as well as mutual aid and community advocacy, were key resources as the pandemic revealed the weakness of the U.S. social safety net’s provisions, even for citizens. Mujeres Unidas y Activas and its membership had weathered periods of intensified stress and crisis in its first thirty years. These include intensification of xenophobic state and federal politics targeting low-income women and immigrants in the U.S. as well as economic, political, and environmental crises in their countries of origins that precipitated their migration and continue to impact them as members of transnational families and networks. The organization itself has experienced crises as well, including the sudden closure of its first fiscal sponsor, which prompted a skeletal group of staff to work without pay for months to keep the organization alive while they worked with allies to build sustainable, independent administrative and funding systems.

4.1. Core Historical Practice of Apoyo

Mujeres Unidas y Activas’s key goals and priorities include outreach and education to address the needs of low-income immigrant Latina women, end isolation and domestic violence, develop women’s leadership, and advocate for justice for immigrant women, families, and domestic workers. MUA’s organizational model centers the experiences and needs of low-income, Spanish-speaking immigrant women, recognizing the complex ways in which mutually reinforcing structures of violence are at work in their lives. MUA’s understanding and practices of support, or apoyo, are as complex as the needs of its members. Some individual women’s needs may be immediate, including for emotional support, shelter, or legal assistance during crises. MUA built its membership over its first three decades of history primarily through one-on-one outreach, follow-up, and accompaniment as well as referrals from hospitals, schools, and other agencies. MUA trained peer counselors to staff Spanish-language hotlines for women experiencing domestic violence or sexual assault, meet with women who arrive at meetings or the office seeking instrumental support, and refer women who require additional professional mental health support to a therapist who works with MUA members.

MUA’s two offices are centrally located close to public transit and in immigrant neighborhoods of San Francisco and Oakland. During normal, pre-pandemic conditions, activities in MUA offices include general informational meetings, peer support groups, popular education workshops, and extended training courses on topics from childcare to leadership. In-person meetings feature coffee, food, and childcare and are facilitated by members who have extensive leadership training and experience as active members of MUA’s working committees. Facilitators ensured the meetings convey warmth and are welcoming and comforting, knowing that for many women these hours were the only times in the week when women might center their own needs or feel cared for by others.

“(M)e encanta que cuando llegan las mujeres, las facilitadoras ya tienen su cafecito puesto, ya tienen el pan, porque ellas van ahora, lo que yo hacía, ellas van, compran el pan, el queso, la fruta, ponen el café, preparan las sillas, o sea, ellas cuando llegan las miembras ya está todo listo. Entonces, te hacen sentir en casa, ¿verdad?, te hacen sentir que eres bienvenida, te ofrecen una tacita de café, te ofrecen, cómo estás, todo bien, cómo está tu familia, pues bien, pásale.”8“I love that when the women arrive, the facilitators already have their coffee ready, they already have the bread, because they are already doing what I would do, they go, they buy the bread, the cheese, the fruit, they put the coffee to brew, they set up the chairs, and when the members arrive everything is ready. Then they make you feel at home. Right? They make you feel welcome, and they offer you a little cup of coffee, they offer you things, [they ask] how are you, everything is good, how’s your family? Well good, come on in.”

MUA resists political frameworks that distinguish between “providing services” and “organizing to build community power.” The two aspects of the group’s mission are dynamic and co-constructed, which has allowed the organization to change and adjust in response to external pressures and the changing needs of members. Providing care and support in MUA includes developing individual and collective, emotional, and physical resilience. Building deep affective bonds among women is both a means to advance social movement building and a positive social good in and of itself. Through apoyo, MUA helps women heal while also building new skills, capacities, and areas of confidence. Addressing women’s immediate needs is necessary in order to engage them in the forms of political participation, grassroot organizations, and leadership development that they also find healing.

4.2. Core Historical Practice of Liderazgo

MUA built its model of how to develop, promote, and reinforce the leadership of members de la base (“from the base”) of the organization over three decades. MUA staff reflect the base of the organization: over 60% originally joined as rank-and-file members of the base before becoming member-leaders and later hired by the organization. Leadership from the base reflects back the power and potential of members to themselves, starting with the directors of the organization, and also includes the staff and member-leaders.

“Entonces … hay algunas compañeras que vivieron la misma vida que yo, y ya lo superaron. Yo también lo voy a superar y aquí estoy ahorita. Ya lo superé.”9“So, there are some compañeras that have lived the same life as me, and they overcame it. I too will overcome it and am here now. I have overcome it.”

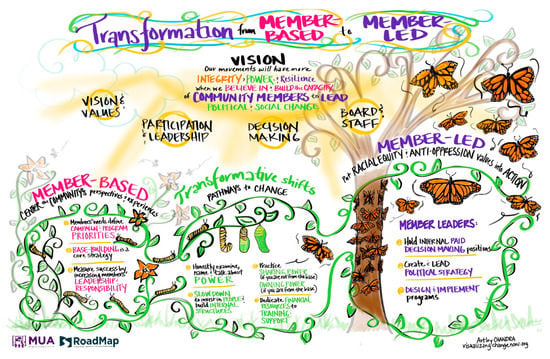

Prior to the pandemic, MUA’s staff organizers and member-leaders conducted regular (one to three times/week) street outreach in parks, on busy street corners, and in shopping centers in San Francisco, Oakland, and Union City, in the San Francisco Bay Area. Staff and member-leaders also offered informational workshops in Spanish at schools and consulates on a variety of topics of interest to immigrants, including parenting skills and resources, immigrant rights, workers’ rights, sexual assault, and domestic violence. MUA also cultivates relationships with service providers who refer Latina immigrants for peer-led services and support. Any woman who regularly attends MUA activities is considered an MUA member. A member-leader is anyone who has graduated from one or more of the intensive leadership training series MUA offers, and who has taken on an active role as a member of the committee. Two-thirds of the staff and one-half of the staff Leadership Team is made up of member-leaders who went on to become paid staff, including the Executive Director and the Programs Director. These commitments and practices have enabled MUA to develop over time from a member-based to a member-led organization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Visual depiction of MUA’s transformation from being a member-based organization to being a member-led organization.10

Leadership in MUA manifests in community building based on welcoming women, accepting and recognizing them without judgment. Family and home life may not provide support or consolation, but women are subject to powerful intersecting structural forms of violence, from economic to legal to intimate partner violence. Speaking of a co-founder of MUA, one of the first members cited key qualities in the orientation of MUA organizers that member from later periods of organizational history emphasized as well.

“Nunca me juzgó porque pasaba violencia doméstica, nunca me dijo ‘déjelo’, nunca me dijo cosas negativas del papá de mis niñas. Y ella nos enseñó eso, esa habilidad de no juzgar a las señoras, de tener pasión, amor, dedicación, sencillez y humildad. Y mucho compromiso.”11“She never judged me because I was going through domestic violence, she never told me to ‘leave him,’ and she never told me negative things about my daughters’ father. And she taught us the ability to not judge women, to have the qualities of passion, love, dedication, simplicity, and humility. And a lot of commitment.”

Respect for women’s self-determination, humility, and vulnerability are powerful values that MUA cultivates through peer role models of leadership that help build confidence in oneself as well as in others. While providing instrumental and emotional support, MUA meetings and activities expose women to peers who share their own stories of transformation through civic engagement, and invite women to participate in popular education activities, informational meetings, and more intensive trainings on diverse topics of interest, such as workplace health and safety, immigration and labor history, challenging patriarchal gender norms in family life and childrearing, and understanding the roots of anti-Blackness and anti-Indigenous racism in Latin America and the U.S. In interviews, women spoke of MUA as their “university” and of the power of learning together with, and led by peers, for the development of their critical consciousness and sense of capacity.

4.3. Core Historical Practice of Confianza

The third key theme that emerged from interviews and focus groups as particularly salient to MUA’s model of community care during the pandemic pertained to trust (confianza) in the organization, in the collective, and in oneself. Building trust is central to the group’s understanding of trauma-informed work with survivors of violence. Until the shift to shelter-in-place and online organizing, MUA meetings always emphasized group agreements and commitments to confidentiality. These meetings were held at the three program sites in San Francisco, Oakland, and Union City, where confidentiality could be ensured, with childcare and refreshments for comfort, where women could speak freely and seek support outside of earshot of their children, extended family or housemates, and where there were private spaces for more intensive support if women needed to speak with a peer or professional counselor one-on-one. These group meetings featured structured activities that helped women explore joyful and traumatic life experiences, and the messages they received about their gender identity growing up and in their families, in service to supporting a positive sense of self and a critical analysis of the forces undermining women’s autoestima (similar, but not identical, to the literal translation of the English language formulation of “self-esteem”) (Coll 2010; Tudela Vásquez 2016).

“De verdad, MUA me transformó. Yo llegué una persona cerrada, no hablaba, pero ahí me hicieron hablar. Escuchando tantas historias de tantas señoras, ahí ya pude hablar… Ahí ya pude hablar.”12“Honestly, MUA transformed me. I came in as a closed person, didn’t talk, but there they got me talking. Listening to all the stories of so many women, then I could talk. Then, I could talk.”

In interviews with new and long-standing members, both groups spoke of the importance of transformational relations to their positive experience in MUA. Not only did women feel transformed themselves, gaining in confidence and ability to speak up for themselves, but they framed their personal processes in relationship to peers. This did not entail a flattening of very real differences in backgrounds or individual histories, but rather reflected a growing consciousness of commonalities and the importance of relationships of solidarity that are so different from the transactional relationships of so much public and political life. Member leaders showed how immigrant women had struggled together for the common good in the past, that the collective had proven itself trustworthy, and that speaking up, working for the common good in the present, could be healing. Members trusted the leadership of the group but also the process that enabled others like them to become leaders, care for one another, and fight for collective concerns.

5. Discussion: Key Adaptations of Historical Practices in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the first years of the pandemic, thirty years of history, core mission and values of the organization became critical resources for individual Mujeres Unidas y Activas staff, membership and the broader community. MUA prioritized community-based mutual aid, peer support, and care for both members and staff while also doing advocacy work to increase access to limited public resources. This involved continuing to focus on engaging new immigrant women members in processes of transforming the structures of power and inequality that subject them to unsustainable levels of structural violence and poor health. Immigrants, especially women who are low-socioeconomic position and who may have a precarious legal status,13 have always experienced exclusion from services, from assistance, and from public health interventions. MUA members’ collective work during the ongoing pandemic challenged notions of any return to “normality” or “recovery” premised upon the ongoing denial of their equality and rights.

5.1. Adapting Apoyo

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on the financial stability, health, and well-being of the women of Mujeres Unidas y Activas. Locally and nationwide, Latina women had the highest rates of income loss and unemployment (Kochhar 2020), far higher than people of any other race/ethnicity and gender. Many organizations and institutions recognized the gaps in aid and the particular fears immigrant families faced and were trying to identify and advocate for community needs during the pandemic. In the San Francisco Bay Area, local governments partnered with community-based organizations (CBOs) and philanthropy to fund cash, food, and rental assistance that the federal government denied mixed-status families. Yet, most public and philanthropic programs utilized screening questions including sensitive topics such as immigration status. While they generally did so in order to help direct applicants to additional sources of support, this created additional stress for those needing aid, and hesitancy on the part of many community members to participate.

In contrast, MUA knew from experience to never ask about immigration status because of the anxiety it generates, and because it can be divisive among members who have different statuses. Instead, MUA staff instead sought emergency aid resources from private sources, such as the National Domestic Workers Alliance’s emergency relief fund, that did not prompt for immigration status. While public health agencies created information campaigns, MUA members and leaders identified specific needs for information, including dispelling dangerous myths about COVID-19 treatment and vaccines, and addressed these through special meetings held entirely in Mam, as well as larger webinars with a native Spanish-speaking physician from UCSF skilled in health education and able to answer questions respectfully and effectively.

While some members’ employers continued paying house cleaners or childcare providers for at least some period of time while they observed shelter-in-place rules, many did not do so, including some who demanded that women work or forego pay altogether. The vast majority of members lost income, and many also experienced hunger and housing insecurity. MUA’s trained peer counselors immediately documented high levels of family conflict and violence and tremendous anxiety over meeting basic needs. Many members live with other families, sometimes strangers, in overcrowded conditions, creating intense levels of stress. Many members are essential workers themselves or live in households with workers unable to shelter-in-place or work from home. Calls to MUA’s crisis line reported economic losses when people were forced to stay home, including loss of work and auto-repossession, and lack of access to key sources of government relief including unemployment due to immigration status or local sources of food due to lack of transportation. As in other communities, use of alcohol and drugs rose overall in response to pandemic stressors, exacerbating household conflict and violence. Crisis line users reported increases in domestic violence as well as sexual harassment and abuse as women became more isolated during shelter-in-place, and many children were left with less adult supervision and fewer structural supports normally provided in schools.

Recognizing the need to treat its own staff members with the care it advocates for its members as workers, MUA closed its offices immediately in mid-March 2020, ceased all in-person activities, and gave staff paid time off to manage the demands of the shift to shelter-in-place on families with children, and modeling compliance with regional public health directives. In this way, MUA’s staff had access to support from their employer in ways that the majority of their peers did not.

When the organization resumed operations remotely, two weeks after the regional shelter-in-place orders began, it did so without salary cuts, layoffs, or furloughs, centering care for staff’s emotional and physical well-being, allocating up to twenty hours of the paid work week for independent self-care activities during the early months of the pandemic, while providing additional leave time to staff experiencing higher levels of family stress. The total number of paid hours allocated for personal needs or self-care was reduced gradually over 2020 and 2021. Beginning in August 2022, staff are now allocated 40 h per year of “personal time” that can be used for self-care or for personal needs, such as parent-teacher meetings or urgent errands.

For an organization traditionally reliant on face-to-face meetings, with low levels of education and technology literacy beyond email, Facebook, and WhatsApp, tech tools had previously seemed to be obstacles or exclusionary barriers, devoid of the warmth and intimacy, the calor humano y cariño, that characterized MUA culture. The pandemic changed that for staff and members alike and that shift required concomitant changes in workload, addressing women’s immediate material needs for health, safety, economic support, and stability. As one member of the Apoyo staff team recalled,

“Nos llamaban a la línea de crisis. Escuchamos mucho las pérdidas económicas por estar encerradas en casa. Muchas perdieron sus coches, por ejemplo, por no poder pagar. La violencia doméstica y acoso sexual aumentó, incluyendo entre los niños, que se ponían a jugar a escondas.”14“They were calling the crisis line. We heard so much about the economic losses due to being forced to stay home. Many lost their cars, for example, because they were not able to pay their payments. Domestic violence and sexual abuse increased, including among children, who were playing, hidden (at home, unsupervised)”.

During the pandemic, MUA carefully adapted apoyo practices for the online mode, using combinations of platforms for different activities such as Zoom, Facebook Live, Facetime, WhatsApp group chats, and even TikTok for creative content production, but also relying on hotlines, warmlines, and individual phone follow-up to approximate the experience of recognition, warmth, and welcome that members valued so much in pre-pandemic times. MUA immediately increased the hours and staffing for its existing regional Spanish language phone helplines, including a sexual assault hotline, receiving over 115 calls in the first two weeks of the pandemic alone. Trained counselors provided peer support and referrals to resources, and when necessary, individual therapy by phone with bilingual licensed clinician. They also referred families to food banks at record levels. MUA developed a widely-viewed Spanish-language COVID-19 resource guide that took into account many members’ precarious immigration statuses and included information on how to apply for relief funds and other relevant health and welfare information for survivors. Indigenous women from Guatemala approached MUA to support them in developing outreach and information about the COVID-19 and available services in Mam, since there was nothing available in that language. MUA trained and hired one of the Mam women organizers and the indigenous women’s group grew quickly in size and impact within the organization and community.

MUA staff and member-leaders mobilized to offer support for old and new members on how participants should download and use Zoom on their phones. They created and moderated multiple Facebook Messenger and WhatsApp private conversation groups for members to provide mutual support. English language, group life coaching, and Zumba fitness classes over Zoom were offered multiple days per week to help provide women with supportive and healthy ways to stay connected with each other while sheltering in place.

The MUA Facebook page subscribers grew to over 6200, with women from as far as Honduras and Guatemala commenting on the benefits they experienced from participating in outreach, education, and self-care meetings and archived video resources. Facebook Live sessions in Spanish twice per week sustained much of the continuity of format and community-building content that characterized pre-pandemic regular MUA meetings. One session focused on tools for self-care and emotional health. These have been conducted in collaboration with facilitating practitioners from NAKA Dance Theater, who provide guidance in trauma-informed healing, dance, and meditation. The other weekly informational meeting provided critical information and updates on shelter-in-place orders, available resources, and civic engagement issues, such as the U.S. Census or COVID-19 testing and vaccine information, that are time sensitive and relevant to MUA’s community. Unable to conduct face-to-face street outreach as usual, MUA launched two new professionally-produced outreach videos using targeted promotions on Facebook, with funding from its sexual assault program. As of April 2023, over 25,000 people had viewed those posts, and over 7000 have watched the videos.

5.2. Adapting Confianza

With the COVID-19 pandemic, trust was an essential resource that MUA systematically sought to build and sustain. Prior to the pandemic, MUA understood the central importance of reducing women’s isolation through building respectful, confidential, and transformative rather than transactional relationships among peers. Positive relational experiences are empowering; they build trust and confidence in oneself and in others. While confidentiality could not be guaranteed in the same way in the online setting, the practice of sharing stories and modeling experiences of transformation continued, albeit with significant attention to the lack of privacy on electronic platforms. The online format not only preserved but expanded many somatic and resilience-building practices that MUA utilized in person, including yoga, meditation, and collaborations with creative and performing artists. Organizers understood that new conditions meant women were attending meetings from home where children and other family members might be present. They took this into account when determining what topics to talk about (or not) and were cognizant of assessing community health and safety needs. Caring and supportive organizers shifted the practices of check-in activities and somatic exercises focused on wellness to the online platforms, even during political and informational meetings. Meditation and exercise classes also moved online, including innovative partnerships with artists that included both expressive arts and political education. While these practices pre-dated the pandemic, they proved important opportunities to assess collective support needs and identify members needing more individual follow-up who were not reaching out for themselves via MUA’s hotline or being referred by health services providers. Online facilitators encouraged women to share in the chat or in discussions, but also encouraged them to reach out individually with more sensitive concerns, or to ask for follow-up one-on-one from a trained peer counselor. Follow-up showed support and caring, but could also lead to substantive assistance, such as helpful information or referrals to trustworthy resources. Members explained that knowing that others care enough to check on them and that they are valued and valuable to individuals and the group, in turn motivated them to participate and engage more deeply with collective projects.

5.3. Adapting Liderazgo

The atmosphere of support, safety, and welcome MUA organizers cultivate in their activities is foundational for the types of critical conversations and dialogues that facilitators initiate and curate in face-to-face meetings. In the online organizing context of Shelter-in-place, these were necessarily slightly more structured, as facilitators worked together to monitor chats and small breakout groups along with field questions in larger group sessions. Remembering their own sentiments as new members, member-leaders worked hard to replicate the experience as best they could online, if not with coffee and sandwiches, with music, movement, informational discussions on topics of pressing interest, and somatic exercises. During the pandemic, MUA relied on leadership of members who reflected, modeled, and encouraged the participation of peers. Building on skills and relationships that they had developed in prior years, MUA leaders managed to transfer the sense of belonging and personal bonds of affection and solidarity to the virtual space. Member leaders and MUA staff projected their familiar faces and key practices in person meetings into Zoom and Facebook Live, encouraging comments, questions, and testimonials from participants, but also adapting in-person check-in, ice-breaker activities, and somatic practices that members recognized as well. They not only maintained contact with members but also strengthened and deepened relationships among existing members while integrating significant numbers of new ones, encouraging them not only to stay but to become new leaders as well. In one indication of the high level of engagement of new members, 50% of the 166 members who responded to the November 2020 membership survey reported having joined during the pandemic.

“La otra parte que siento es, muchas de nosotras, las mujeres, venimos de experiencias donde no hemos sido valoradas, donde no hemos sido respetadas, y cuando llegas allí, puedes sentir eso, que incluso te lo dicen, verdad, como “tú opinión cuenta, tu opinión vale, tu opinión es valiosa.” Entonces, estás sintiendo de que en ese espacio lo que tu dices, lo que tu haces, o lo que tu eres, es aceptado. Y es cuando tú sientes de verdad que estás formando parte de algo.”15“The other thing that I feel is, a lot of us feel, the women, is that we have experiences where we have not been valued, where we were not respected, and when we arrive here, we feel that, that they even tell you personally, right, like, “your opinion matters, your opinion is worthy, your opinion is valuable.” Then, you feel that in this space, what you say, what you do, and who you are is accepted. And that is when you really feel that you are becoming a part of something.”

MUA’s long-term commitment to worker rights and experience in policy advocacy, such as crafting legislation and lobbying, also helped in the transition to a fully online model during the pandemic. The committee structure within MUA and parallel structures of member consultation and decision-making were already in place, existing members had experienced these activities face-to-face and in the state capital in the past, while new members were introduced to them via meetings conducted on Zoom and Facebook live. Both new and continuing members learned about the issues and gained skills and experience with policy-making and lobbying, while observing the impact of their own participation through the committee structure.

5.4. Advances Made during the Pandemic

Mujeres Unidas y Activas entered the pandemic with thirty years of experience, expertise, and skill in balancing advocacy with care. The practices of welcome, acceptance, and support that members felt in person and online are critical aspects of both MUA’s dual mission and their political projects. During the pandemic, MUA relied heavily on its existing practices of showing, giving and receiving care, both listening and responding to the needs of both its staff and members.

“Yo creo que sentir ese calor humano, esa parte de familia. Nosotras que como inmigrantes, muchas de nosotras no tenemos, yo creo que es muy importante esa forma en la que somos recibidas y tratadas en MUA.”16“I think that to feel human warmth, like you are part of the family. We immigrants, a lot of us do not have [family], and I think it is very important the way they receive and treat us at MUA.”

Historically, in order to avoid being limited, in reputation or functioning, to a direct-services oriented institution, and to avoid dynamics of dependency and clientelism, MUA avoided disbursing cash benefits or in-kind relief aid as a routine part of its core work. The impact of the pandemic on MUA’s base and the immigrant community prompted internal discussion and the conclusion that MUA needed to help address the immediate material needs of its membership, and indeed of staff as well. MUA created and disbursed its first ever emergency relief fund to active MUA participants who lost income due to the current crisis, providing cash relief to over 650 families in addition to partner organizations in the California Domestic Worker Coalition in both Northern and Southern California, and creating a food distribution program for members lacking transportation to food banks and school meal distribution sites.

MUA has no immediate plans to change its traditional approach or continue disbursing material and economic aid on a mass scale as it did during the first months of the pandemic. During that period, addressing women’s material survival needs was the first care the community needed. Doing so without any promise or expectation of ongoing economic aid, while continuing to support developing members’ sense of political power and leadership, mitigated against developing new dynamics of clientelism or dependence during this exceptional period. Processes of community consultation and grassroot participation generated practices of community care that inspired the trust of existing members, reactivated older members, and engaged new members who have, to date, only participated online. This built the sense of belonging and accountability to the collective from women who in turn “showed up” for virtual organizing and advocacy, including remote phone banking in Spanish on state and federal campaigns, while also helping craft new legislation and lobbying elected officials for domestic worker and immigrant rights. The experience and solidarity built in these campaigns further reinforced women’s confidence in their own leadership and capacity to not only survive but learn and develop even as they sustained and persisted through personal grief and loss due to COVID-19 as well as political setbacks in policy campaigns.

Basing their response on the pandemic in participatory practices such as the committee structure produced effective, inclusive, and sensitive representation of the base that also reinforced trust in leadership and the collective. MUA’s leadership structures build a sense of belonging, rights, and responsibilities, not just to the organization, but to the broader society through campaigns and public political participation. Civic political work prior to the pandemic brought women together outside the office to attend marches, rallies, hearings at City Hall. and lobbying at the state capital in Sacramento. The committee structure engaged members in making decisions, setting priorities, and sharing activities. MUA found they were able to continue this committee structure online, meeting on Zoom internally and also as part of larger coalitions. This mode of organizing, which predated the pandemic, helped continue to build trust and confidence in the collective, in decision-making processes that guided political and resource priorities.

“Creo que son una manera de que las compañeras se sientan parte, pertenencia de Mujeres Unidas y Activas, porque su opinión cuenta. Por ejemplo, en las trabajadoras del hogar si tenemos algunos cambios en las leyes, también formamos los grupos para que ellas puedan dar su opinión sobre si están de acuerdo como trabajadoras o no. Y hacer esos cambios… Es involucrarlas en todo, tanto en las celebraciones como en los talleres, los comités, como decía, los comités de liderazgo en donde ellas están liderando también para dar su opinión sobre que campaña estamos llevando y cuáles creen que sería mejor apoyar. Les da el sentido de pertenencia ser parte de lo que MUA hace.”17“I think they [the committees] are a way for the members to feel that they are part of it, I mean that they belong to Mujeres Unidas y Activas, because their opinion counts. For example, in domestic workers if we have some changes in the laws, we also form groups so that we can give our opinion on whether we agree as workers or not. And [then we] make those changes … [The point] is to involve them in everything, both in the celebrations and in the workshops, the committees, as I said, the leadership committees where they are leading also to give their opinion on what campaign we are carrying out and which ones they think would be better to support. This gives them a sense of belonging, to be part of what MUA does.”

Having a trusted source for good information and a safe place to ask questions and learn is in itself an invaluable resource for immigrant community members at any time, but especially during a crisis. MUA’s ability to continue modeling caring relationships alongside transparent and trustworthy processes, such as in the committee structure, enabled effective campaign work and civic engagement. Through nurturing grassroot leadership, demonstrating care for members, and building trust in one another, MUA was able to continue and grow its work during the pandemic, building transformational organizing relationships than strictly transactional ones (Christens 2010; Pastor et al. 2011). The care that staff as well as members received in the group, the incorporation of new members and reactivation of old ones, undergirded MUA’s organizing power by adapting remote/online formats in ways that were consistent with face-to-face organizing culture of the group. Because MUA showed up for members, as it did for its own staff during shelter-in-place, women also showed up for each other. During critical moments when MUA needed to demonstrate the power of its base, old and new members showed up both for internal committee work meetings but also the public work of electoral, statewide, and local legislative campaigns.

6. Conclusions

While the full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is still unknown, the first years of the pandemic offered important insights into the potential of transformative political work led by low-socioeconomic position immigrant women of color to address immediate community needs while highlighting root causes of social disparities along lines of race, class, gender, sexuality, and national origin. Our findings add further evidence that small and medium-sized local–regional organizations like MUA that employ intersectional feminist models of grassroot leadership are critical resources for service providers, policy makers, and community-engaged scholar-educators. Such organizations are positioned to help advance “just recovery” efforts able to both address immediate needs and transform structures of inequality. They warrant not only increased attention, but also sustained support for their core operations and organizing activities both in the U.S. and internationally (UN Women 2021).

Over its 30-year history of organizing, MUA developed practices and politics of care for members. Grounded in values of mutuality, interdependence, and the integration of direct services to women in crisis, MUA developed its own institutional strength alongside members’ leadership as advocates for their rights as women, workers, and migrants. One lesson of the pandemic is that these decades of careful, principled work provided the foundation for the organization to face the challenges of COVID-19. Practices of liderazgo, apoyo and confianza proved themselves to be particularly potent, effective tools in sustaining individual women and the collective.

“(S)i pasa algo como esta crisis, si pasa algún incendio, ellas son muy innovadoras en hacer proyectos y esto es lo que ha hecho que MUA no va a llegar solamente a los 30 años, va a llegar a los 50, a los 60 años. Por ese carácter que tienen de fortaleza y habilidad para saber qué hacer en tiempos de tempestades y en tiempos difíciles. Y yo lo he visto así en la trayectoria de Mujeres Unidas…¡Listas! a ver qué vamos a hacer.”18“If something like this crisis happens, or if there is a massive fire, these women are very innovative [in launching new] projects, and this is why MUA will not go on for just 30 years, it will last 50, 60 years, because of that character they have of strength and ability to know what to do in times of storms and in difficult times. And I have seen it that way in the trajectory of Mujeres Unidas y Activas … Ready! Let us see what we are going to do.”

MUA’s experience balancing and integrating service provision with community organization enabled them to pivot quickly and effectively to prioritize addressing basic needs, not instead of, but in order to advance their efforts for structural change. Caring for members and staff during the pandemic entailed not only providing immediate support, but also building and sustaining the emotional and physical resilience that individuals and the collective need to enact longer term transformations. While the nature of the pandemic is different from other challenges, MUA had previously encountered both through members’ own and the collective’s experience of surviving precarity and exclusion were key resources MUA relied on to survive and look forward to a better future.

“Con pandemia o sin pandemia los inmigrantes, las mujeres de la base, somos excluidos. Los servicios, la ayuda, hasta la vacuna no era para nosotras. Queremos una normalidad con derechos, servicios, igualdad para todos. Regresar a la normalidad es seguir luchando por nuestros derechos e igualdad.”19“With the pandemic or without the pandemic, the immigrants, the women from the base, are excluded. The services, the aid, even the vaccine was not [designed] for us [to be included]. We want the normalization of rights and services and equality for all. To return to normal, is to keep fighting for our rights and equality.”

Our research confirmed that core values and practices of care in transformational, relational organizing were not only effective in “normal” times, but also critical for sustaining the organization and members through extreme crises. Practices that promote the integration of care for mind, body, and spirit, including learning about the root causes of structural violence and inequity with direct engagement in policy advocacy, can be both healing and politically empowering. At the same time, the stress of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to pose significant challenges to members and staff in their own health, homes, families, and work. Members and staff long to see one another again and miss the in-person culture of the organization and its activities. Some new members who have never participated in in-person meetings or exercises focused on transformative personal development, self-esteem, and desahogo, or sharing through “getting things off one’s chest” may find these new experiences challenging after being accustomed to more bounded online activities. While MUA responded to the increase in calls to their domestic violence and sexual assault helplines by providing more hours of service and trained counselors, it is possible that other survivors in need were missed due to the lack of opportunities for face-to-face exchanges that often occurred in meetings in MUA offices. In addition, due to the lack of confidentiality possible in the full online context, the partner organizations that provided MUA members training and credentialling in domestic violence and sexual assault counseling have stopped providing new counselor training since the beginning of shelter-in-place. While training partners did offer refresher courses in telephone and online counseling with COVID-19 in mind, no new counselor training occurred for over 18 months. There is likely to be a significant backlog in need for domestic violence and sexual assault volunteer counselors both inside and outside of MUA.

This research also led to an expansion of MUA’s definition of aprendizaje as an asset-based ethical frame that views everyday people not as objects of inquiry, but as political and social analysts (Rosaldo 1989), actors, learners, and producers of knowledge. Learning together in service to transforming social, legal, and economic structures that limit their flourishing are key components of individual and collective well-being. True critical community-based participatory research requires integration with these broader processes in any organization or movement aiming to build the power of the subjects of research. In practice, even in an organization with the experience of MUA, with a research team drawn from across the organization, such integration and communication between the researchers and other staff and members was difficult to obtain. The exigencies and pressures of the pandemic clearly played a role in stretching research team capacity. At the same time, this experience leaves MUA better prepared to evaluate potential research partnerships and proposals, anticipate and ensure adequate resources to promote research as a leadership and skill-building opportunity, and better integrate research activities, analysis, and dissemination into ongoing organizing and service provision programs.

The longer-term institutional impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are very much yet to be determined and are already the subject of further investigation and reflection within MUA. For example, despite efforts to structure paid time for self-care into staff calendars, the workload has continued to increase during the pandemic in the process of building the online organizing models. While personal outreach and one-on-one follow-up were long-standing practices, they became even more important and time-consuming for member leaders and peer counselors during shelter-in-place. Pre-existing differences in and disparate access to resources and support needs among members, also evident among staff who came from the membership, were exacerbated in the pandemic context. Despite efforts to account for increased work and family pressures that staff experienced, the same devotion of staff to their work, the innovations, and new projects developed since March 2020 meant that self-care often fell to the wayside. As in other workplaces, women and parents continue to carry a disproportionate burden for the economic and human impacts of the pandemic, shelter-in-place, and work/schooling from home. Along with the rest of the nonprofit sector of organizations led by people of color, serving people of color, MUA is faced with the implications of continued suffering at the community level due to enduring social and economic crises after the pandemic (Building Movement Project 2021).

MUA’s experience indicates implications for other community-based organizations, health professionals, academics, policy makers, and funders. Trust is the foundation upon which transformative relationships can be built, and undergirds organization that builds collective power while deeply supporting individuals. This approach to politics and community organizing transforms people’s sense of themselves and their power through respectful and accountable relationships among peers, with a shared set of values and vision for both intimate and structural change. These practices are particularly important for working with survivors of trauma, a category of persons that was already growing prior to the collective grief and trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic. Funders and policy makers should commit to ongoing support to sustain this kind of work. The need for such human infrastructure is independent of the pandemic, but MUA’s thirty years of experience, skills, and trust-based relationships were critical resources for immigrant women both in the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond. Health professionals and academics should recognize the expertise of community-based organizations like MUA, that have many years of experience and community trust, as they seek to understand and address community needs. Community organizers and community members are more than objects of study or recipients of services, they are peers and social analysts in their own right (Rosaldo 1989). Health equity has become a potent frame for organizations working to advance social justice by addressing the root-causes of social inequality that constitute key structural determinants of health inequity (Pastor et al. 2018). In an era in which public faith in both public institutions and science itself are in question, researchers, public health providers, and policy makers have much to learn from immigrant women and organizations like MUA about how we might build and maintain the public trust required to advance scientific knowledge, transformational social movements, and more just and effective public policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Formal Analysis: K.M.C., A.K.C., J.F., M.J. and A.L.L.; Methodology, Investigation: K.M.C., A.K.C., M.C., L.C., A.D., E.D., J.F., M.J., A.L.L., N.L., H.M., S.L., V.N. and M.R.; Validation: L.C., M.C., E.D., A.D., J.F., M.J., A.L.L., N.L., S.L., H.M., V.N. and M.R.; Writing—original draft, K.M.C., A.K.C., A.L.L. and N.L.; Writing—review and editing, K.M.C., A.K.C., J.F., M.J., A.L.L. and T.B.Q.; Project administration, Supervision, K.M.C., A.K.C., J.F., M.J. and A.L.L.; Funding acquisition, K.M.C., A.K.C., J.F. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [Grant Number 77300].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects (IRBPHS) at the University of San Francisco (USF), IRB Protocol #1418 (Base-Building, Leadership Development & Overcoming Violence Among Latina Immigrants: Mujeres Unidas y Activas), 10 July 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all interview participants.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the members, current and former staff, and allies of Mujeres Unidas y Activas who kindly contributed to this project. In particular, Yael Falicov’s contributions at every phase of the manuscript’s development, from conceptualization to analysis to fact-checking, strengthened the paper significantly. Malena Mayorga, Emily Goldfarb and Jill Shenker each offered important feedback at key phases of this project. We are also grateful to Gabriela L. Ruelas’ contributions, including her editorial assistance preparing final drafts for submission. Rachel Brahinsky, Candice Harrison and Stephanie Sears provided careful comments on multiple drafts that significantly strengthened the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This paper employs multiple suffixes to convey gender inclusivity following the current practice in the community of study. Organizational leaders use different terms to signal respect and recognition in different contexts, both orally (e.g., compañeres, hijes) and in writing (latinas, latinx). |

| 2 | This paper refers to MUA in the third person to distinguish the organization as a whole from the coauthors, which includes the research team of organizational leaders, staff, and academic collaborators. We use the first person to refer to ourselves as researchers. |

| 3 | While most members speak Spanish, in November 2021, among the members, 9% of respondents identified an indigenous language as their preferred language (mostly Mam, a Guatemalan Mayan language, but also Yucatecan Maya). |

| 4 | “Active members” participate in regular support group meetings and/or training programs. In addition to active members, MUA reaches over 1500 women per year through their outreach and education activities. |

| 5 | Authors 2–3, 7–14. |

| 6 | Authors 1, 5, and 16, with Authors 4 and 15 and other graduate student research assistants who participated for shorter periods. |

| 7 | The University of San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study. |

| 8 | MUA member interview 13, 13 July 2020. |

| 9 | MUA member interview 34, 15 October 2020. |

| 10 | Figure 1 used with permission of Mujeres Unidas y Activas, 2018. |

| 11 | MUA member interview 23, 4 September 2020. |

| 12 | MUA member interview 15, 24 July 2020. |

| 13 | We use terms such as “precarious status” and “without immigration status” rather than the term “undocumented” throughout this article. Most MUA members have documents, though they may not be recognized by the US for immigration purposes. There are many legal immigration statuses, such as DACA, TPS, and Visa U/V, that are precarious; even legal permanent residency is revocable. For Mexicans in the US, birthright citizenship has also historically failed to protect against removal, most famously with the depression-era mass deportations. “Il/legality” and “un/documented” categories are dynamic, complex, and contested. |

| 14 | MUA Program Director María Jiménez, also a co-author, comment in research team meeting, 18 August 2021. |

| 15 | MUA member interview 14, 23 July 2020. |

| 16 | MUA member interview 18, 31 July 2020. |

| 17 | See note 16 above. |

| 18 | See note 11 above. |

| 19 | MUA Executive Director Juana Flores, also a coauthor, comment in research team meeting, 18 August 2021. |

References

- Bernstein, Hamutal, Dulce Gonzalez, Michael Karpman, and Stephen Zuckerman. 2020. Amid Confusion over the Public Charge Rule, Immigrant Families Continued Avoiding Public Benefits in 2019. Urban Institute. Available online: http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102221/amid-confusion-over-the-public-charge-rule-immigrant-families-continued-avoiding-public-benefits-in-2019_1.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Bibbins-Domingo, Kirsten, Maya Petersen, and Diane Havlir. 2021. Taking vaccine to where the virus is—Equity and effectiveness in Coronavirus vaccinations. JAMA Health Forum 2: 210–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloemraad, Irene, and Veronica Terriquez. 2016. Cultures of engagement: The organizational foundations of advancing health in immigrant and low-income communities of color. Social Science and Medicine 165: 214–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Building Movement Project. 2021. On the Frontlines: Nonprofits Led by People of Color Confront COVID-19 and Structural Racism. Available online: https://buildingmovement.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/On-the-Frontlines-COVID-Leaders-of-Color-Final-10.2.20.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Castañeda, Heidi, Seth M. Holmes, Daniel S. Madrigal, Maria Elena de Trinidad Young, Naomi Beyeler, and James Quesada. 2015. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health 36: 375–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamie, Gabriel, Carina Marquez, Emily Crawford, James Peng, Maya Petersen, Daniel Schwab, Joshua Schwab, Jackie Martinez, Diane Jones, Douglas Black, and et al. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 community transmission during shelter-in-place in San Francisco. Clinical Infectious Disease 73 S2: S127–S135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez, Vivian, Meredith Minkler, Nina Wallerstein, and Michael S. Spencer. 2007. Community organizing for health and social justice. In Prevention Is Primary: Strategies for Community Well Being. Edited by Larry Cohen, Vivian Chávez and Sana Chehimi. Washington, DC: Jossey-Bass & the American Public Health Association, pp. 87–112. [Google Scholar]

- Christens, Brian D. 2010. Public relationship building in grassroots community organizing: Relational intervention for individual and systems change. Journal of Community Psychology 38: 886–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Jennifer Jihye, George Lipsitz, and Young Shin. 2013. Intersectionality as a social movement strategy: Asian immigrant women advocates. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38: 917–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Alison K., Rachel Brahinsky, Kathleen M. Coll, and Miranda P. Dotson. 2022. “We Keep Each Other Safe”: San Francisco Bay Area Community-Based Organizations Respond to Enduring Crises in the COVID-19 Era. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 8: 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, Kathleen M. 2010. Remaking Citizenship: Latina Immigrants and New American Politics. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Graauw, Els. 2016. Making Immigrant Rights Real: Nonprofits and the Politics of Integration in San Francisco. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Gaitán, Concha. 2001. The Power of Community: Mobilizing for Family and Schooling. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Zita, Melissa L. Bessaha, and Margaret Post. 2018. Beyond the ballot: Immigrant integration through civic engagement and advocacy. Race and Social Problems 10: 366–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fimrite, Peter. 2020. Coronavirus cases Across the Bay Area top 50,000. San Francisco Chronicle. June 29. Available online: https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Bay-Area-coronavirus-cases-poised-to-top-50-000-15440780.php (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Fine, Michelle, and Maria Elena Torre. 2019. Critical Participatory Action Research: A Feminist Project for Validity and Solidarity. Psychology of Women Quarterly 43: 433–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, David M., Michelle Fine, Maria Elena Torre, and Allison Cabana. 2019. Minority stress, activism and health in the context of economic precarity: A National participatory study of LGBTQ youth. American Journal of Community Psychology 63: 511–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, Marc A., Patricia A. Homan, Catherine García, and Tyson H. Brown. 2021. The color of COVID-19: Structural racism and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on older black and Latinx adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 76: 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, Emily, and Anita Wadhwani, eds. 1999. Caught at the Public Policy Crossroads: The Impact of Welfare Reform on Battered Immigrant Women. San Francisco: Family Violence Prevention Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon da Cruz, Cynthia. 2017. Community-Engaged Scholarship: Communities and Universities Striving for Racial Justice. Peabody Journal of Education 41: 147–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, Mary. 2005. Popular Education and the Methodology of Learning to Adapt to Life in the US. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Department of Education, Rutgers University, Rutgers, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmo, Jennifer, and Michelle Joffroy. 2020. A History of Domestic Work and Worker Organizing. Available online: https://www.dwherstories.com/film (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Hogeland, Christine, and Karen Rosen. 1990. Dreams Lost, Dreams Found: Undocumented Women in the Land of Opportunity. San Francisco: Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights and Services. Available online: https://niwaplibrary.wcl.american.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/IMM-Rsch-DreamsLostDreamsFound.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Ito, Jennifer, Rachel Rosner, Vanessa Carter, and Manuel Pastor. 2014. Transforming Lives, Transforming Movement Building: Lessons from the National Domestic Workers Alliance Strategy-Organizing-Leadership Initiative. Los Angeles: USC Dornsife Program for Environmental and Regional Equity (PERE). Available online: https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/242/docs/sol-transforming-lives-executive-summary-4.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2021).

- Jang, Deena, Debbie Lee, and Rachel Morello-Frosch. 1990. Domestic Violence in Immigrant and Refugee Communities: Responding to the Needs of Immigrant Women. Response to the Victimization of Women and Children 13: 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Deena, Lena Marin, and Gayle Pendleton, eds. 1997. Domestic Violence in Immigrant and Refugee Communities, rev. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Family Violence Prevention Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Kochhar, Rakesh. 2020. Hispanic Women, Immigrants, Young Adults, Those with Less Education Hit Hardest by COVID-19 Job Losses. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/09/hispanic-women-immigrants-young-adults-those-with-less-education-hit-hardest-by-covid-19-job-losses/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Minkler, Meredith, and Nina Wallerstein. 2012. Improving Health Through Community Organization and Community Building: Perspectives from Health Education and Social Work. In Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare. Edited by Meredith Minkler. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Tania D., and Kathleen M. Coll. 2017. Ethnic Studies as a Site for Political Education: Critical Service Learning and the California Domestic Worker Bill of Rights. PS: Political Science and Politics 50: 187–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa Camacho, Ariana. 2006. Chisme Fresco! A Critical Ethnography of Microresistance and Microtransformation by Latina Immigrants. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Department of Communication, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor, Manuel, Jennifer Ito, and Rachel Rosner. 2011. Transactions, Transformations, Translations: Metrics that Matter for Building, Scaling, and Funding Social Movements. Los Angeles: USC Program for Environmental and Regional Equity. Available online: https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/242/docs/transactions_transformations_translations_web.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Pastor, Manuel, Veronica Terriquez, and May Lin. 2018. How community organizing promotes health equity, and how health equity affects organizing. Health Affairs 37: 358–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, S. Karthick, and Irene Bloemraad, eds. 2008. Civic Hopes, and Political Realities: Immigrants, Community Organizations, and Political Engagement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]