Diverse Social Mobility Trajectories: Portrait of Children of New Immigrants in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

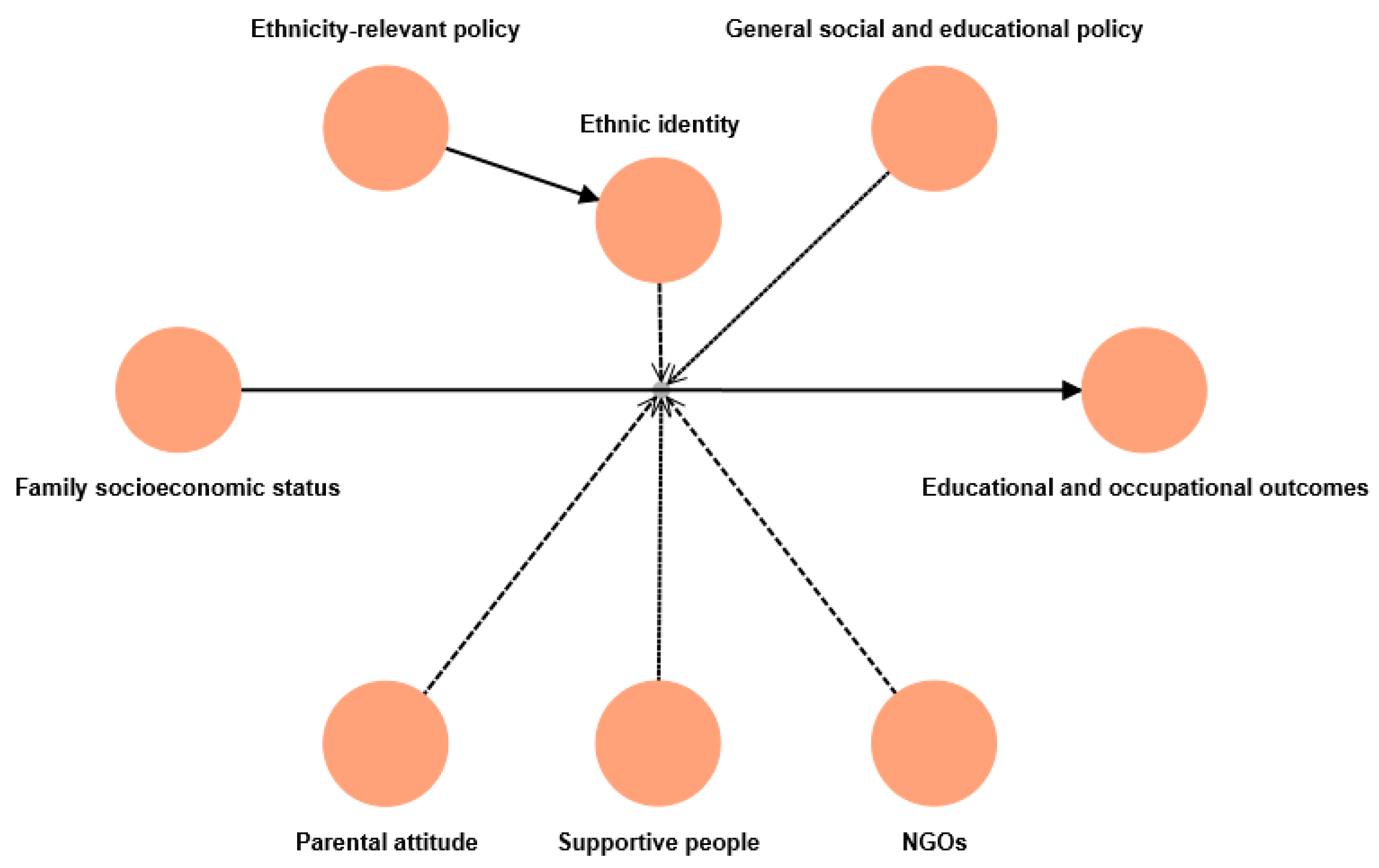

- How do children of new immigrants take advantage of opportunities created by micro and macro factors?

- How do children of new immigrants overcome barriers posed by micro and macro factors?

2. New Immigrants and Their Children

3. Social Mobility in Taiwan

4. Research Methodology

4.1. A Mixed-Methods Approach

4.2. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. Educational and Occupational Attainment in Early Adulthood

5.2. Family Socioeconomic Status

5.3. Parental Attitude toward Education

5.4. Supportive People

5.5. Christian Church and Non-Governmental Organizations

5.6. Ethnic Identity

5.7. Government Policy

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Family Socioeconomic Status Matters but Can Be Moderated by a Range of Factors

6.2. Ethnic Identity Is Irrelevant in General but Sometimes Plays a Role Due to Relevant Policy

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Questions

- A.

- Background

- Could you describe your education and jobs?

- Could you tell me about your family background?

- Could you describe your spouse and children if you are married?

- What did the neighborhoods where you lived during childhood and adolescence look like?

- B.

- Success factors and barriersWhat made you reach your current educational and occupational levels?

- What was the role of your parents/siblings?

- What was the role of your ambition?

- Could you describe your choices regarding schools, majors, and careers and others’ influence on you?

- Who or what do you consider crucial for your trajectory?

- Would your trajectory be different if you wouldn’t have been a child of new immigrants; would have been a woman/man; would have lived in a different neighborhood?

- What opportunities and barriers have you encountered?

- C.

- Social context

- How was/is your relation with parents, siblings, and friends?

- Who were/are your friends? (Primary & secondary school, university, now)

- How would you describe your relation with your parents/siblings? (then/now)

- Did you feel at home at school/in the neighborhood? Why?

- With which people/at which places do you feel at home most? Why?

- With which people/at which places do you feel at home less? Why?

- D.

- Ethnic identification

- To what extent do you identify with the ethnic majority? What does that mean to you?

- To what extent do you identify with your immigrant heritage? What does that mean to you?

- Do you identify more with the ethnic majority or your immigrant heritage? Why?

- How do you define yourself?

References

- American Institute in Taiwan. 2021. 2020 International Religious Freedom Report: Taiwan Part. May 17. Available online: https://www.ait.org.tw/taiwan-2020-international-religious-freedom-report (accessed on 9 December 2022).

- Arce, Carlos H., Edward Murguia, and W. Parker Frisbie. 1987. Phenotype and Life Chances Among Chicanos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 9: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behtoui, Alireza. 2013. Incorporation of children of immigrants: The case of descendants of immigrants from Turkey in Sweden. Ethnic and Racial Studies 36: 2141–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, H. Russell, and Gery W. Ryan. 1998. Text analysis: Qualitative and quantitative methods. In Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology. Edited by H. Russell Bernard. Walnut Creek: Alta Mira, pp. 595–646. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John Richardson. Westport: Greenwood, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bygren, Magnus, and Ryszard Szulkin. 2010. Ethnic Environment During Childhood and the Educational Attainment of Immigrant Children in Sweden. Social Forces 88: 1305–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Soo-yong, and Hyunjoon Park. 2012. The academic success of East Asian American youth: The role of shadow education. Sociology of Education 85: 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Soo-Yong, Hee Jin Chung, and David P. Baker. 2018. Global Patterns of the Use of Shadow Education: Student, Family, and National Influences. Research in the Sociology of Education 20: 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Hou-Sheng, and Fen-Ling Chen. 2014. An Analysis of the Disadvantaged Situation of Foreign Spouses in Taiwan. Taipei: National Policy Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Pao-Hwa, and Weigh-Jen Chen. 2021. Gaozhongzhi ji dazhuan xiaoyuan xinzhumin zinu zhiya guihua yu duoyuan fazhan zhi yanjiu 高中職及大專校院新住民子女職涯規劃與多元發展之研究 [A Study of the Career Planning and Diverse Development of Children of New Immigrants in High School and College]; Taipei: Ministry of the Interior.

- Chang, Fang-Chung. 2021. The related factors of junior high school students’ examination results: Evidence from Penghu County data. School Administrators 133: 203–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Yu-Ju, Kai-Cheng Han, Yi-Jin Liu, and Xin-Yi Song. 2021. Xinzhumin zinu zhiya fazhan zhi yanjiu 新住民子女職涯發展之研究 [A Study of the Career Development of Children of New Immigrants]; Taipei: Ministry of the Interior.

- Chen, Chih-jou Jay, and Ka U. Ng Wu. 2017. Public attitudes toward marriage migrants in Taiwan: The ten-year change, 2004–2014. Journal of Social Sciences and Philosophy 29: 415–52. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Chun-Wei, and Yih-Jyh Hwang. 2011. A re-exploration of stratification and efficacy in cram schooling: An extension of the Wisconsin model. Bulletin of Educational Research 57: 101–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Ko-Jen, Lyau Nyan-Myau, and Fei-Chuan Chen. 2017. A study of the influence of family education resources and academic performance on educational tracking for economically disadvantaged high school students. Educational Policy Forum 20: 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Wan-chi. 2005. Ethnicity, gender and class: Ethnic difference in Taiwan’s educational attainment revisited. Taiwanese Sociology 10: 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Wen-Hao, and Feng Hou. 2019. Social Mobility and Labor Market Outcomes Among the Second Generation of Racial Minority Immigrants in Canada. Social Science Quarterly 100: 885–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, Joseph Meng-Chun, and Sen-Chi Yu. 2008. School Adjustment among Children of Immigrant Mothers in Taiwan. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 36: 1141–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Ai-Ling, and Ching-Jung Ho. 2008. A survey of the status, characteristics and difficulties surrounding the implementation of education for new immigrants by new immigrant education institutes in Taiwan. NTTU Educational Research Journal 19: 61–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, Chuing. 2008. Taiwan jiaoyu zenmeban? 台灣教育怎麼辦? [What Should Taiwan Do with Its Education?]. New Taipei: Psychological Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, Yih-Chyi, and Yeng-Ling Chen. 2011. Education and social mobility in Taiwan. Journal of Social Sciences and Philosophy 23: 61–91. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, James. 1968. The Concept of Equality of Educational Opportunity. Harvard Educational Review 38: 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Indigenous Peoples. 2021. 110 nian diyiji yuanzhuminzu jiuye zhuangkuang diaocha baogao 110年第1季原住民族就業狀況調查報告書 [A Report on Indigenous Employment Status in the First Quarter of 2021]; New Taipei: Council of Indigenous Peoples.

- Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics. 2020. Report on the Survey of Family Income and Expenditure, 2019; Taipei: Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics.

- Edin, Per-Anders, Peter Fredriksson, and Olof Åslund. 2003. Ethnic Enclaves and the Economic Success of Immigrants--Evidence from a Natural Experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118: 329–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrich, Steve R. 2014. Effects of investments in out-of-school education in Germany and Japan. Contemporary Japan 26: 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Yuan. 2021. 110 nian 3 yue gongye ji fuwuye xinzi tongji jieguo 110年3月工業及服務業薪資統計結果 [Statistics of the Average Salary of Employees in the Manufacturing and Service Industries, March, 2021]; Taipei: Executive Yuan.

- Executive Yuan. 2022a. Jiaoyu xiankuang 教育現況 [Education]. Guoqing jianjie 國情簡介 [Taiwan at Glance]. March 18. Available online: https://www.ey.gov.tw/state/7F30E01184C37F0E/130f6b11-b1d8-445c-859f-470e79e4ac15 (accessed on 11 October 2022).

- Executive Yuan. 2022b. 110 nian gongye ji fuwuye shougu yuangong quannian zongxinzi zhongweishu ji fenbu tongji jieguo 110年工業及服務業受僱員工全年總薪資中位數及分布統計結果 [Statistics of the Annual Income Medians of Employees in the Manufacturing and Service Industries and Their Distributions]. December 21. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=2716&s=230415 (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- Executive Yuan. n.d.a. Shiwusui yishang renkou jiaoyu Chengdu 十五歲以上人口教育程度 [Population of 15 Years and over by Educational Attainment]. Available online: https://www.gender.ey.gov.tw/gecdb/Stat_Statistics_Query.aspx?sn=Mm4ACreYMwEr7cuT6no39g%40%40&statsn=MUwvQW33tN8mhRl94KFn2g%40%40 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Executive Yuan. n.d.b. Zhongdeng jiaoyu jieduan biyesheng shengxuelu 中等教育階段畢業生升學率 [Percentage of Graduates in Secondary Education Entering Schools at the Next Stage]. Available online: https://www.gender.ey.gov.tw/gecdb/Stat_Statistics_Query.aspx?sn=q01ZZsaeNXFcMezQRWFAKQ%40%40&statsn=zFBdChdKABRonydFjA%24hgg%40%40&d=&n=199560 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Fan, Yun, and Chin-fen Chang. 2010. The effects of social structural positions on ethnic differences of higher educational achievements in Taiwan. Taiwan: A Radical Quarterly in Social Studies 79: 259–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, Fenella, Karen Phalet, Karel Neels, and Patrick Deboosere. 2011. Contextualizing Ethnic Educational Inequality: The Role of Stability and Quality of Neighborhoods and Ethnic Density in Second-Generation Attainment. International Migration Review 45: 386–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Eric, and Jing Shen. 2011. Explaining ethnic enclave, ethnic entrepreneurial and employment niches: A case study of Chinese in Canadian immigrant gateway cities. Urban Studies 48: 1605–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Jon E., and Demelza Jones. 2013. Migration, everyday life and the ethnicity bias. Ethnicities 13: 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, Guy G. 1994. Integrating case study and survey research methods: An example in information systems. European Journal of Information Systems 3: 112–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganzeboom, Harry B. G., Paul M. De Graaf, and Donald J. Treiman. 1992. A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research 21: 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin-White, Jamie. 2009. Emerging Contexts of Second-Generation Labour Markets in the United States. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35: 1105–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog-Punzenberger, Barbara. 2003. Ethnic Segmentation in School and Labor Market—40 Year Legacy of Austrian Guestworker Policy. International Migration Review 37: 1120–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Ming-Chuan, and Jin-Chang Hsieh. 2013. Meta analysis: Difference of academic performance between native and new-immigrant children. Journal of Education & Psychology 36: 119–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Fu-Chen, and Hsin-Mu Chen. 2004. Fanshu + yutou = Taiwan tudou?—Taiwan dangqian zuqun rentong zhuangkuang bijiao fenxi 蕃薯 + 芋頭 = 臺灣土豆?—臺灣當前族群認同狀況比較分析 [An Analysis of Ethnic Identification in Today’s Taiwan] [Conference Session]. Population Association of Taiwan 2004 Annual Meeting. Taipei: National Taiwan University. [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh, Cherng-Tay. 1996. Analyzing the family background effect on the tracking of post-junior high education. Taiwanese Journal of Sociology 20: 49–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Chih-Pei, and Ya-Fang Hsiao. 2012. The study of the new immigrants’ children education policies implementation in Taipei City Municipal Elementary School of Wenshan District. The Journal of Chinese Public Administration 11: 123–53. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Jou-Li, and Yih-Fen Chen. 2016. A study on Vietnam female immigrants’ Chinese learning experience in Taiwan. NCUE Journal of Educational Research 28–29: 103–26. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Ming-Fu, and Yih-Jyh Hwang. 2014. Correlation among students’ family background, academic performance in junior high school, and senior high school tracking in Taiwan. Journal of Educational Practice and Research 27: 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Yih-Jyh, and Hui-Min Lin. 2016. Individual education, accessed and mobilized social capital, and status attainment. Bulletin of Educational Research 62: 97–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Richard. 2000. The limits of identity: Ethnicity, conflict, and politics. Sheffield Online Papers in Social Research 2: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Richard. 2008. Rethinking Ethnicity, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Jhang, Fang-Hua, and Yeau-Tarn Lee. 2018. The role of parental involvement in academic achievement trajectories of elementary school children with Southeast Asian and Taiwanese mothers. International Journal of Educational Research 89: 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jick, Todd D. 1979. Mixing Qualitative and Quantitative Methods: Triangulation in Action. Administrative Science Quarterly 24: 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. Burke, and Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie. 2004. Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educational Researcher 33: 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalbach, Madeline A., Kelly H. Hardwick, Renata D. Vintila, and Warren E. Kalbach. 2002. Ethnic-connectedness and economic inequality: A persisting relationship. Canadian Studies in Population 29: 245–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Rebecca Y. 2002. Ethnic differences in academic achievement between Vietnamese and Cambodian children: Cultural and structural explanations. The Sociological Quarterly 43: 213–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Kai-Ying. 2017. An Ethnic Identity Study of the New Immigrants’ Adult Offsprings in Taiwan. Unpublished. Master’s thesis, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

- Kroneberg, Clemens. 2008. Ethnic Communities and School Performance among the New Second Generation in the United States: Testing the Theory of Segmented Assimilation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 620: 138–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuan, Ping-Yin, and Duen-Yi Lee. 2010. Effects of cram schooling on math performance in junior high: A propensity score matching approach. Bulletin of Educational Research 56: 105–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, Annette. 2000. Home Advantage: Social Class and Parental Intervention in Elementary Education, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jennifer, and Min Zhou. 2014. From unassimilable to exceptional: The rise of Asian Americans and “Stereotype Promise”. New Diversities 16: 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Mei-Hsien, and Ho-Chia Chueh. 2018. The image of the “New Second Generation” in Taiwan’s mainstream newspapers. Communication, Culture & Politics 7: 133–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Pei-Huan, and Yih-Jyh Hwang. 2010. Aboriginals and Hans, family background and their relationship with the Basic Competence Test, and educational tracking: A study in Taitung. Journal of Research in Education Sciences 56: 193–226. [Google Scholar]

- Lessard-Phillips, Laurence, Rosita Fibbi, and Philippe Wanner. 2012. Assessing the labour market position and its determinants for the second generation. In The European Second Generation Compared: Does the Integration Context Matter. Edited by Maurice Crul, Jens Schneider and Frans Lelie. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 165–224. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Cheng-Chieh, and Yuk-Ying Tung. 2018. The influential mechanism of students’ educational aspiration among Hans, aborigines, and new immigrants in Taiwan. Education Journal 46: 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Caryn. 2017. Being ‘mixed’ in Malaysia: Negotiating ethnic identity in a racialized context. In Mixed Race in Asia: Past, Present and Future. Edited by Zarine L. Rocha and Farida Fozdar. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 117–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Siu-Theh, Chi-Ping Huang, and Tai-Yuan Li. 2016. Woguo zuqun fazhan zhengce zhi yanjiu 我國族群發展政策之研究 [A Study of the Development of Ethnic Policy in Taiwan]; Taipei: National Development Council.

- Lin, Da-Sen, and Yi-Fen Chen. 2006. Cram school attendance and college entrance exam scores of senior high school students in Taiwan. Bulletin of Educational Research 52: 35–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Eric S., and Yu-Lung Lu. 2016. The educational achievement of pupils with immigrant and native mothers: Evidence from Taiwan. Asia Pacific Journal of Education 36: 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Hui-Min, and Yih-Jyh Hwang. 2009. The study on relationship among the Aborigines and Hans, cram schooling and the academic achievement: The example of the eighth graders in Taitung. Contemporary Educational Research Quarterly 17: 41–81. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Ta-Sen. 1999. The effects of family background on tracking of secondary education in Taiwan: A study of the distinction between “academic/vocational” and “public/private” tracking. Soochow Journal of Sociology 8: 35–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Yi-Shyuan, and Thuy-Linh Pham. 2015. Dongnanya xinzhumin yuwen lieru shiernian guomin jiben jiaoyu kecheng gangyao dui xinzhumin zinu jiaoyu zhi yingxiang 東南亞新住民語文列入「十二年國民基本教育課程綱要」對新住民子女教育之影響 [The impact of the incorporation of Southeast Asian immigrants’ languages into the compulsory education curriculum on the education of new immigrants’ children]. Taiwan Educational Review Monthly 4: 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jeng. 2006. The transition, efficacy, and stratification of cram schooling in Taiwan. Bulletin of Educational Research 52: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Luoh, Ming-Ching. 2001. Differences in educational attainment across ethnic and gender groups in Taiwan. Taiwan Economic Review 29: 117–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Tsai-Chuan, Huo-Shen Chan, Der-Hsing Li, Liang-Xun Jiang, and Thi Huyen Duong. 2018. Xinzhumin ji qi zinu chuangye moshi yu fuzhu celue zhi yanjiu 新住民及其子女創業模式與輔助策略之研究 [A Study of the Entrepreneurship Models of New Immigrants and Their Children and Relevant Guidance Strategies]; Taipei: Ministry of the Interior.

- Maes, Julie, Jonas Wood, and Karel Neels. 2019. Early labour market trajectories of intermediate and second generation Turkish and Maghreb women in Belgium. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 61: 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. 2016a. Jiaoyubu xinzhumin jiaoyu yangcai jihua 教育部新住民教育揚才計畫 [New Immigrant Talent Cultivation Plan]; Taipei: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education. 2016b. Jiaoyubu buzhu gaoji zhongdeng xuexiao xuesheng xuefei you 7 cheng yue 54 wan ming xuesheng shouyi shuoming 教育部補助高級中等學校學生學費有7成約54萬名學生受益說明 [70% of High School Students, or about 540,000 Students Benefitted from Tuition Subsidies Offered by the Ministry of Education]. Ministry of Education. October 17. Available online: https://www.edu.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=9E7AC85F1954DDA8&s=42EE5BA1C2DE5D17 (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Ministry of Education. 2022. 110 xueniandu geji xuexiao xinzhumin zinu jiuxue gaikuang 110學年度各級學校新住民子女就學概況 [The Distribution of Children of New Immigrants in the Taiwanese Educational System, School Year 2021–2022]; Taipei: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education. n.d. K-12 Education Administration, Ministry of Education. Available online: https://www.k12ea.gov.tw/Tw/Unique/FAQDetail?cate1_id=C0C06A62-A856-48BB-A410-9E9C361BE503&Keywords=&filter=C49CFCC1-11D8-49BD-AFB8-95856E82E58D&page=0 (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Ministry of the Interior. 2020. Available online: https://ws.moi.gov.tw/001/Upload/OldFile/site_stuff/321/2/year/year_en.html#7%20Immigration (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Modood, Tariq. 2004. Capitals, ethnic identity and educational qualifications. Cultural Trends 13: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, Joane. 1994. Constructing ethnicity: Creating and recreating ethnic identity and culture. Social Problems 41: 152–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Immigration Agency. 2020. 107 nian xinzhumin shenghuo xuqiu diaocha baogao 107年新住民生活需求調查報告 [2018 Survey Report of New Immigrants’ Living Needs]; Taipei: National Immigration Agency.

- National Immigration Agency. 2023. Waiji peiou renshu yu dalu (han gangao) peiou renshu an zhengjian fen 11201 外籍配偶人數與大陸(含港澳)配偶人數按證件分 11201 [Foreign Spouses by Legal Status, January 2023]. Available online: https://www.immigration.gov.tw/5385/7344/7350/8887/?alias=settledown (accessed on 11 March 2023).

- Panico, Lidia, and James Y. Nazroo. 2011. The social and economic circumstances of mixed ethnicity children in the UK: Findings from the Millennium Cohort Study. Ethnic and Racial Studies 34: 1421–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Hyunjoon, Soo-yong Byun, and Kyung-keun Kim. 2011. Parental involvement and students’ cognitive outcomes in Korea: Focusing on private tutoring. Sociology of Education 84: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Li-Hui, R. Hsung, and Chin-Shan Chi. 2011. How cohort, gender, and gendered majors affect the acquirement of first job’s SES in the context of Taiwan’s higher education expansion. Taiwan Journal of Sociology of Education 11: 47–85. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, Alejandro, and Dag MacLeod. 1996. Educational Progress of Children of Immigrants: The Roles of Class, Ethnicity, and School Context. Sociology of Education 69: 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro, and Min Zhou. 1993. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530: 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro, and Robert D. Manning. 2006. The immigrant enclave: Theory and empirical examples. In Inequality: Classic Readings in Race, Class, and Gender. Edited by Grusky David and Szonja Szelenyi. New York: Routledge, pp. 161–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut, Rubén G. 2008. The Coming of the Second Generation: Immigration and Ethnic Mobility in Southern California. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 620: 196–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Jens, and Christine Lang. 2014. Social mobility, habitus and identity formation in the Turkish-German second generation. New Diversities 16: 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Silberman, Roxane, Richard Alba, and Irène Fournier. 2007. Segmented assimilation in France? Discrimination in the labour market against the second generation. Ethnic and Racial Studies 30: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slootman, Marieke. 2018. Ethnic Identity, Social Mobility and the Role of Soulmates. Cham: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, David Lee, and David P. Baker. 1992. Shadow Education and Allocation in Formal Schooling: Transition to University in Japan. American Journal of Sociology 97: 1639–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Kuo-hsien, and Wei-hsin Yu. 2007. When social reproduction fails: Explaining the decreasing ethnic gap in Taiwan. Taiwanese Journal of Sociology 39: 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Ching-Shan, and Yih-Jyh Hwang. 1994. Social resources, cultural capital and occupational attainment. Tunghai Journal 35: 127–50. [Google Scholar]

- Taiwan Academy of Banking and Finance. 2020. Available online: https://www.fsc.gov.tw/en/home.jsp?id=5&parentpath=0 (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Tao, Hung-Lin, Ching-Chen Yin, and Chia-Yu Hung. 2015. Educational performance differences between groups of children with native or denizened parents in subsequent grades. Journal of Social Sciences and Philosophy 27: 289–322. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Van C., Jennifer Lee, and Tiffany J. Huang. 2019. Revisiting the Asian second-generation advantage. Ethnic and Racial Studies 42: 2248–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Shu-Ling. 1998. The transition from school to work in Taiwan. In From School to Work: A Comparative Study of Educational Qualifications and Occupational Destinations. Edited by Yossi Shavit and Walter Muller. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 443–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tsay, Ruey-Ming. 1999. A structural analysis of social mobility in Taiwan, the United States, and Japan. Taiwanese Journal of Sociology 22: 83–125. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, Steven. 2010. Towards post-multiculturalism? Changing communities, conditions and contexts of diversity. International Social Science Journal 61: 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chen-Yun, Hsin-Hui Huang, and Shu-Jing He. 2012. Xinyimin jiating fumu jiaoyang zinu de wenti yu yinying celue zhi tantao 新移民家庭父母教養子女的問題與因應策略之探討 [Exploring parenting issues in new-immigrant families and corresponding solutions]. Journal of Family Education Bimonthly 37: 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Chien-Lung, Chin-Yi Cho, and Ju-Hui Chang. 2021. Indigenous status identification, educational secured admission, and ethnic identity development: The case study of the offspring from Han-Chinese/indigene intermarriage family. Kaohsiung Normal University Journal 51: 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yi-Han. 2011. “My marital life is hard, but I am not pitiful!” Analyzing Southeast Asian immigrant wives’ lives in Taiwan through strengths perspective. NTU Social Work Review 23: 93–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wessendorf, Susanne. 2014. ‘Being open, but sometimes closed’. Conviviality in a super-diverse London neighbourhood. European Journal of Cultural Studies 17: 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, Amanda, and Selvaraj Velayutham. 2014. Conviviality in everyday multiculturalism: Some brief comparisons between Singapore and Sydney. European Journal of Cultural Studies 17: 406–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Chi-Hsin, Tsai-Chuan Ma, Ke-Jeng Lan, Yu-Shu Fan, and Yi-Ting Huang. 2015. Xinzhumin dierdai kuaguo jiuye kexingxing yanjiu 新住民第二代跨國就業可行性研究 [A Study of the Feasibility of Transnational Employment for the New Second Generation]; Taipei: Ministry of the Interior.

- Wu, Huo-Ying. 2007. Family background and educational achievement in Taiwan: Changing trends in five cohorts. Journal of Population Studies 34: 109–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Nai-teh. 2013. Ethnic differences in higher education attainment: Generation, tuition subsidies and public sector employment. Taiwanese Journal of Sociology 52: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, You-I, and Yih-Jyh Hwang. 2009. Are the achievements of mountain indigenous students lower than those of plain indigenous ones? The possible mechanisms of academic achievement gap among the indigenous tribes and the Han elementary school students in Taitung. Taiwan Journal of Sociology of Education 9: 41–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Yuh-Yin, and Chen-Chou Tsai. 2014. Are they really lagging behind?: A three-year longitudinal comparison of academic performance between the Southeast Asian female immigrants’ children and the local children. Bulletin of Educational Research 60: 77–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Chin-Chun, and Ying-Hwa Chang. 2006. Attitudes toward having a foreign daughter-in-law: The importance of social contact. Taiwanese Sociology 12: 191–232. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Ching-Chen, Hung-Lin Tao, and Chia-Yu Hung. 2012. The effects of cram school on the performance in the college entrance examination in Taiwan. Taiwan Economic Review 40: 73–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Min. 1992. Chinatown: The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 30 | 42.25 |

| Female | 41 | 57.75 |

| Age | ||

| Under 20 | 18 | 25.35 |

| 20–29 | 47 | 66.20 |

| 30–39 | 6 | 8.45 |

| Education | ||

| High school | 7 | 9.86 |

| Associate | 3 | 4.23 |

| College | 55 | 77.46 |

| Master’s | 6 | 8.45 |

| Father’s ethnic background | ||

| Taiwanese | 61 | 85.92 |

| Mainland Chinese | 3 | 4.23 |

| Southeast Asian | 7 | 9.86 |

| Mother’s ethnic background | ||

| Taiwanese | 5 | 7.04 |

| Mainland Chinese | 14 | 19.72 |

| Southeast Asian | 52 | 73.24 |

| Participant | Gender | Age | Education | Job | Father’s Ethnic Background | Mother’s Ethnic Background | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jie | M | 32 | master’s | college lecturer | Hoklo | Chinese Vietnamese |

| 2 | Zi | F | 23 | bachelor’s | cosmetic clinic front desk administrator | Hoklo | mainland Chinese |

| 3 | Ling | F | 21 | associate’s | professional soldier | Hakka | Vietnamese |

| 4 | Liang | M | 24 | bachelor’s | high school PE teacher | Matsunese | mainland Chinese |

| 5 | Yi | F | 22 | associate’s | hair stylist assistant | Hoklo | Indonesian |

| 6 | Ming | M | 38 | bachelor’s | NGO project coordinator | mainlander | Hakka Indonesian |

| 7 | Tian | F | 19 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Chinese Laotian | Filipina |

| 8 | Hui | F | 23 | high school | factory worker | Hoklo | Filipina |

| 9 | Jin | F | 35 | master’s | professional writer | mainlander | Hakka Indonesian |

| 10 | Ting | F | 28 | master’s | international company logistics coordinator | Hoklo | Chinese Malaysian |

| 11 | Yuan | M | 27 | bachelor’s | media company camera assistant | Hoklo | Chinese Malaysian |

| 12 | Hong | F | 19 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | mainland Chinese | mainland Chinese |

| 13 | Zhao | F | 20 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Chinese Indonesian |

| 14 | Xuan | F | 20 | associate’s | hospital nurse | Hoklo | Vietnamese |

| 15 | Cai | F | 27 | master’s | consulting firm strategic planning coordinator | Chinese Vietnamese | Chinese Vietnamese |

| 16 | Rui | M | 22 | bachelor’s (in progress) | automotive service technician | mainlander | mainland Chinese |

| 17 | Shan | F | 25 | master’s (in progress) | graduate student | Hoklo | Thai |

| 18 | Jing | M | 20 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Chinese Malaysian |

| 19 | Peng | M | 20 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Thai | Atayal (indigenous) |

| 20 | Shi | M | 19 | high school | family business gofer | Hoklo | Vietnamese |

| 21 | Xian | M | 24 | bachelor’s | freelance graphic designer | Hoklo | Chinese Filipina |

| 22 | Xin | F | 20 | high school | restaurant server | Hoklo | Thai |

| 23 | Ying | F | 20 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Chinese Indonesian |

| 24 | Lin | F | 22 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Chinese Burmese | Vietnamese |

| 25 | Guo | M | 21 | high school | convenient store cashier | Hoklo | mainland Chinese |

| 26 | Wen | F | 22 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Chinese Vietnamese |

| 27 | Yu | F | 21 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Chinese Vietnamese |

| 28 | Qing | F | 24 | bachelor’s | cram school English teacher | Mainland Chinese | mainland Chinese |

| 29 | Qi | F | 21 | bachelor’s (in progress) | digital media editing assistant | Hoklo | Chinese Vietnamese |

| 30 | Jun | F | 23 | bachelor’s | international company sales assistant | Hoklo | Burmese |

| 31 | Yan | M | 25 | bachelor’s | government agency contract worker | Chinese Burmese | Burmese |

| 32 | Zhi | M | 24 | bachelor’s | hotel accountant | Hoklo | Hakka Indonesian |

| 33 | Lai | M | 21 | Bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hakka | mainland Chinese |

| 34 | Wan | F | 23 | bachelor’s | beautician | Hoklo | Vietnamese |

| 35 | Cheng | M | 30 | bachelor’s | factory production supervisor | Hoklo | Chinese Vietnamese |

| 36 | Sheng | M | 22 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Chinese Vietnamese |

| 37 | Wei | F | 21 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Kinmenese | Chinese Indonesian |

| 38 | Liao | F | 18 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | mainland Chinese |

| 39 | Rong | F | 19 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Vietnamese |

| 40 | Chang | M | 22 | bachelor’s | job hunting | Hoklo | Hakka Indonesian |

| 41 | Hua | F | 21 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Vietnamese |

| 42 | Han | F | 22 | bachelor’s (in progress) | college student | Hoklo | Vietnamese |

| Respondent | Father | Mother | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of education | 15.28 (1.70) | 11.43 (3.21) | 10.26 (3.94) |

| (p < 0.001) | (p < 0.001) | ||

| Occupational status | 43.78 (12.54) | 39.95 (13.46) | 33.85 (11.74) |

| (p = 0.131) | (p < 0.001) | ||

| Monthly income | 36,481.48 (14,941.07) | NA | NA |

| Age < 25 | Age 25–29 | Age 30–39 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National median | 359,000 | 479,000 | 541,000 |

| Respondent | 396,000 | 460,000 | 590,000 |

| (n = 52, p = 0.225) | (n = 9, p = 0.666) | (n = 6, p = 0.565) |

| Years of Education | Occupational Status | Monthly Income | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southeast Asian (n = 55) | 15.30 | 42.46 | 36,219.51 |

| Mainland Chinese (n = 16) | 15.18 | 48.90 | 37,307.69 |

| (p = 0.819) | (p = 0.216) | (p = 0.839) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsou, T.-R. Diverse Social Mobility Trajectories: Portrait of Children of New Immigrants in Taiwan. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040226

Tsou T-R. Diverse Social Mobility Trajectories: Portrait of Children of New Immigrants in Taiwan. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(4):226. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040226

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsou, Tzung-Ruei. 2023. "Diverse Social Mobility Trajectories: Portrait of Children of New Immigrants in Taiwan" Social Sciences 12, no. 4: 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040226

APA StyleTsou, T.-R. (2023). Diverse Social Mobility Trajectories: Portrait of Children of New Immigrants in Taiwan. Social Sciences, 12(4), 226. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040226