Click Surveillance of Your Partner! Digital Violence among University Students in England

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

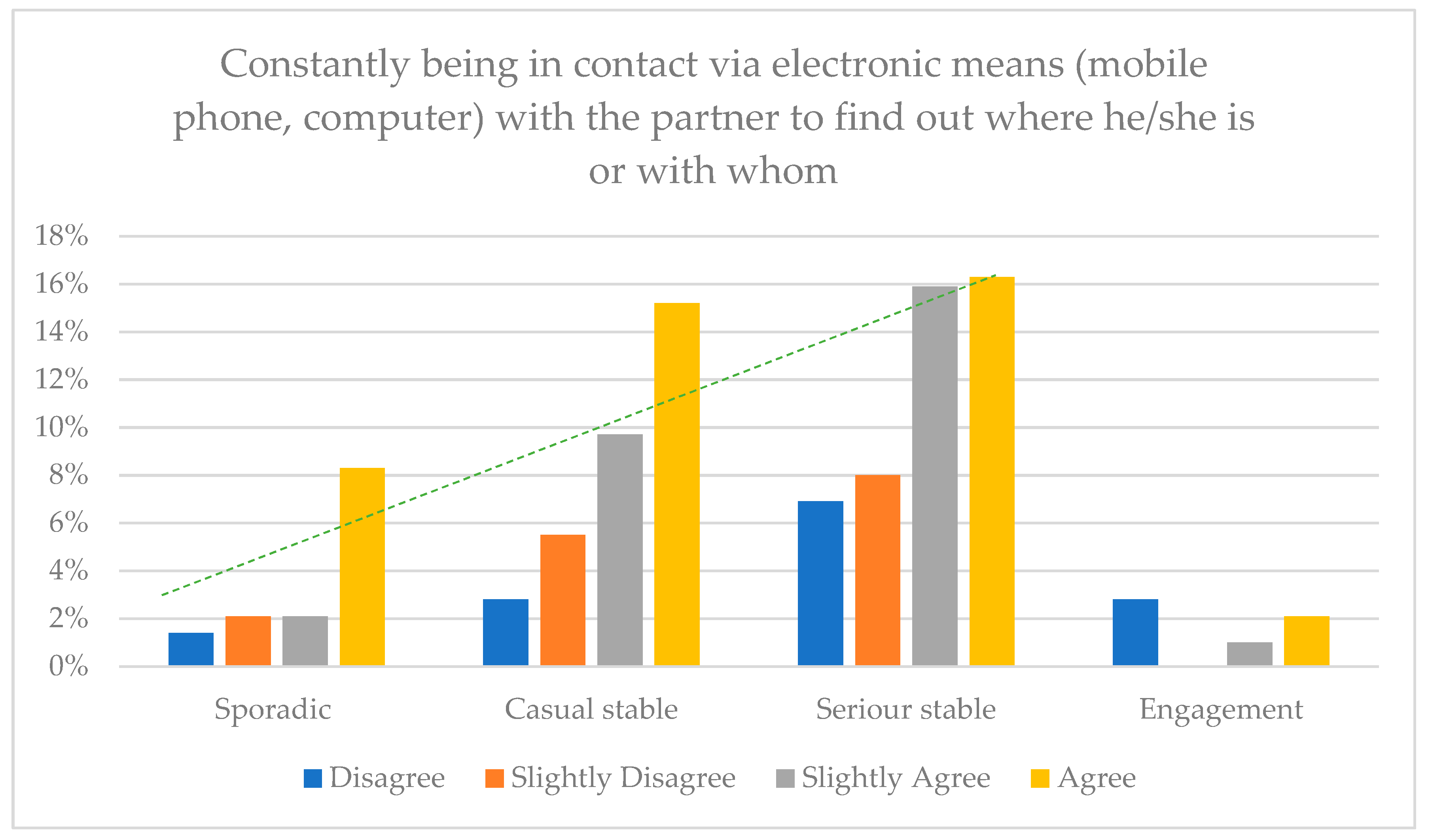

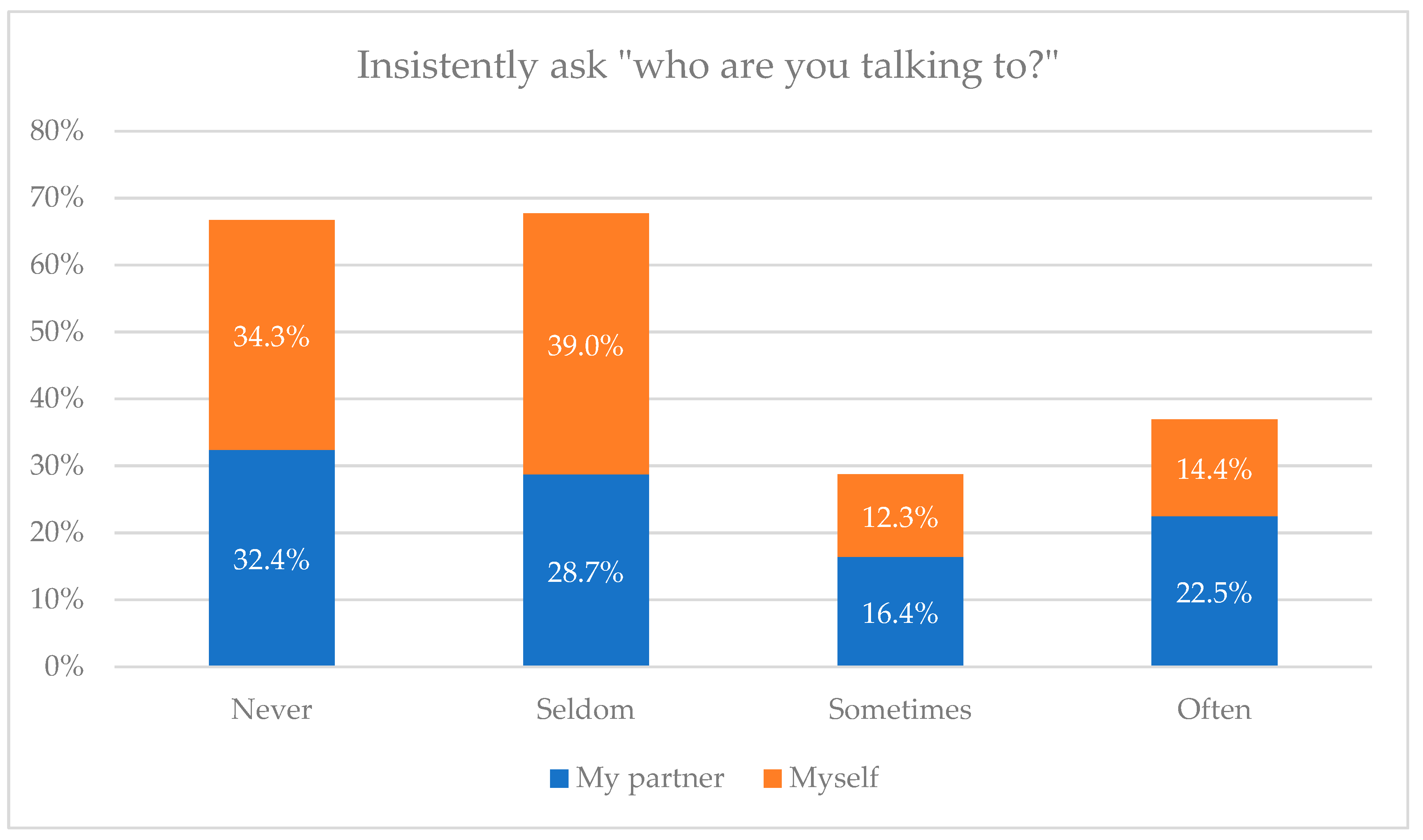

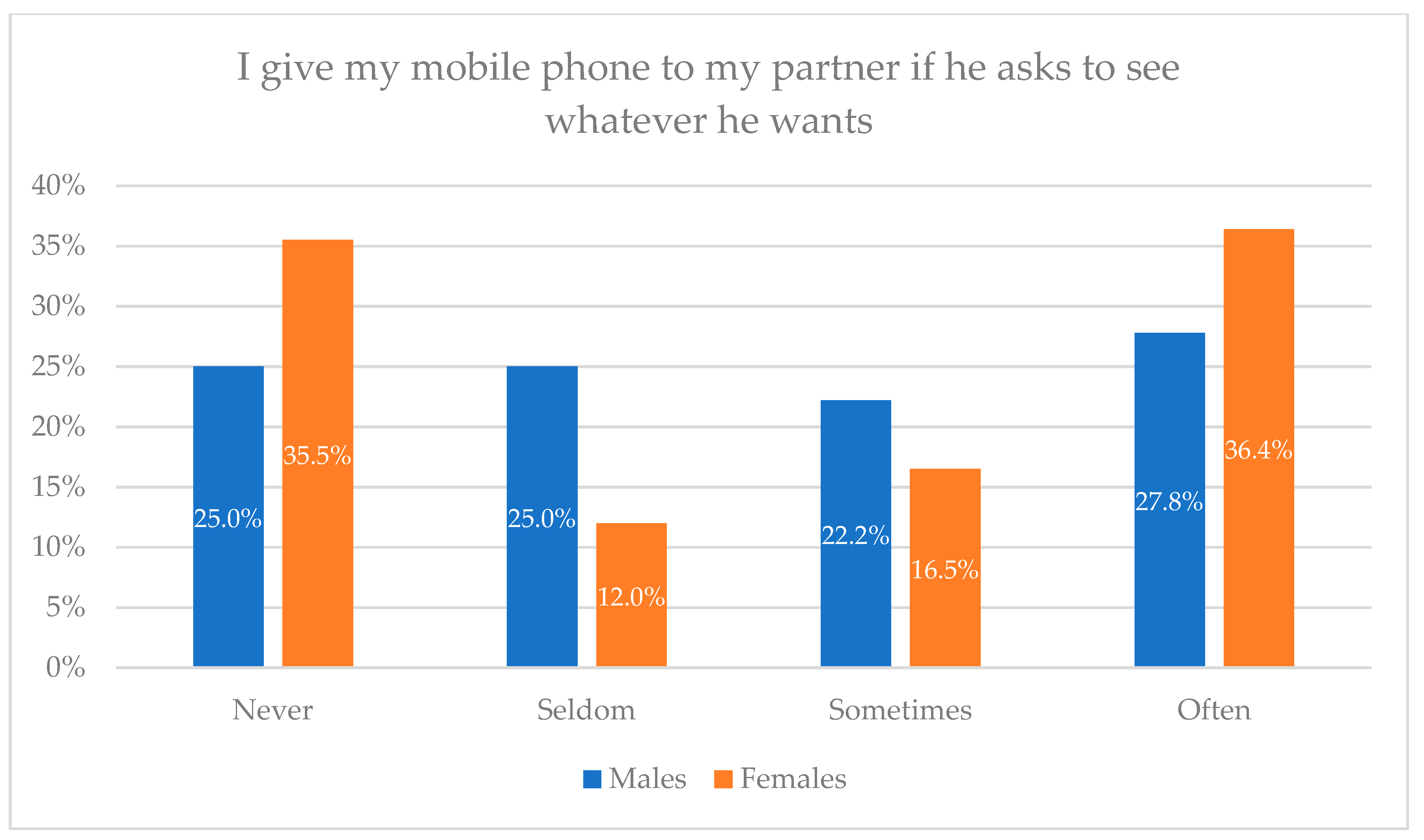

3.1. Instrument 1: Questionnaire

3.2. Instrument 2: Focus Group Discussion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acquadro Maran, Daniela, and Tatiana Begotti. 2019. Prevalence of Cyberstalking and Previous Offline Victimization in a Sample of Italian University Students. Social Sciences 8: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albero, Cristóbal Torres, José Manuel Robles, and Stefano de Marco. 2013. El ciberacoso como forma de ejercer la violencia de género en la juventud: Un riesgo en la sociedad de la información y del conocimiento. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Available online: https://violenciagenero.igualdad.gob.es/violenciaEnCifras/estudios/colecciones/pdf/Libro_18_Ciberacoso.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Alonso, Gemma Teso, and José Luis Piñuel Raigada. 2014. Multitarea, Multipantalla Y Práctica Social Del Consumo De Medios Entre Los Jóvenes De 16 a 29 Años En España. María José Arrojo Baliña 93. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, Mike J., and Stephen L. Bainbridge. 2017. Manchester’s Cyberstalked 18–30s: Factors Affecting Cyberstalking. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billedo, Cherrie Joy, Peter Kerkhof, and Catrin Finkenauer. 2015. The Use of Social Networking Sites for Relationship Maintenance in Long-Distance and Geographically Close Romantic Relationships. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 18: 152–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrajo, Erika, Manuel Gámez-Guadix, Noemí Pereda, and Esther Calvete. 2015. The Development and Validation of the Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire among Young Couples. Computers in Human Behavior 48: 358–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrajo Mena, Erika, and Manuel Gámez Guadix. 2015. Comportamientos, Motivos Y Reacciones Asociadas a La Victimización Del Abuso Online En El Noviazgo: Un Análisis Cualitativo. Journal of Victimology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Fiol, Esperanza, and Victoria Aurora Ferrer-Perez. 2019. The Pyramid Model: A Feminist Alternative for Analysing Violence against Women. Revista Estudos Feministas 27: e54189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossler, Adam M., Thomas J. Holt, and David C. May. 2012. Predicting Online Harassment Victimization among a Juvenile Population. Youth & Society 44: 500–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, Anna, Marian Duggan, and Louise Livesey. 2022. Researching Students’ Experiences of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence and Harassment: Reflections and Recommendations from Surveys of Three Uk Heis. Social Sciences 11: 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello Cádiz, Patricio. 2013. A Qualitative Approach to the Use of Icts and Its Risks among Socially Disadvantaged Early Adolescents and Adolescents in Madrid, Spain. Communications-The European Journal of Communication Research 38: 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, Jennifer, Debra Pepler, Wendy Craig, and Ali Taradash. 2000. Dating experiences of bullies in early adolescence. Child Maltreatment 5: 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, John W., Vicky L. Plano Clark, Michelle L. Gutmann, and William E. Hanson. 2003. Advanced mixed methods research designs. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, 1st ed. Edited by Abbas M. Tashakkori and Charles B. Teddlie. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 209–40. [Google Scholar]

- Deans, Heather, and Manpal Singh Bhogal. 2019. Perpetrating Cyber Dating Abuse: A Brief Report on the Role of Aggression, Romantic Jealousy and Gender. Current Psychology 38: 1077–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeKeseredy, Walter S., Martin D. Schwartz, Bridget Harris, Delanie Woodlock, James Nolan, and Amanda Hall-Sanchez. 2019. Technology-Facilitated Stalking and Unwanted Sexual Messages/Images in a College Campus Community: The Role of Negative Peer Support. Sage Open 9: 2158244019828231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreßing, Harald, Josef Bailer, Anne Anders, Henriette Wagner, and Christine Gallas. 2014. Cyberstalking in a Large Sample of Social Network Users: Prevalence, Characteristics, and Impact Upon Victims. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 17: 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elphinston, Rachel A., and Patricia Noller. 2011. Time to Face It! Facebook Intrusion and the Implications for Romantic Jealousy and Relationship Satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking 14: 631–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gijón, Gracia, and Andrés Soriano-Díaz. 2021. Análisis Psicométrico De Una Escala Para La Detección De La Violencia En Las Relaciones De Pareja En Jóvenes. RELIEVE. Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, Monique M. 2007. International Focus Group Research: A Handbook for the Health and Social Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja, Sameer, and Justin W. Patchin. 2011. Electronic Dating Violence. Thousand Oaks: Cyberbullying Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaitzaki, Argyroula. 2020. Cyberstalking Victimization and Perpetration among Young Adults: Prevalence and Correlates. In Recent Advances in Digital Media Impacts on Identity, Sexuality, and Relationships. Pennsylvania: IGI Global, pp. 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, Puneet, Amandeep Dhir, Anushree Tandon, Ebtesam A. Alzeiby, and Abeer Ahmed Abohassan. 2021. A Systematic Literature Review on Cyberstalking. An Analysis of Past Achievements and Future Promises. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 163: 120426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labonté, Thalie, Caroline Dugal, Marie-France Lafontaine, Audrey Brassard, and Katherin Péloquin. 2021. How do partner support, psychological aggression, and attachment anxiety contribute to distressed couples’ relationship outcomes? Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 48: 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leukfeldt, Eric Rutger, and Majid Yar. 2016. Applying routine activity theory to cybercrime: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Deviant Behavior 37: 263–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, Harold A., and Murray Turoff. 1975. The Delphi Method. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Lyndon, Amy, Jennifer Bonds-Raacke, and Alyssa D. Cratty. 2011. College Students’ Facebook Stalking of Ex-Partners. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14: 711–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcum, Catherine D., and George E. Higgins. 2021. A Systematic Review of Cyberstalking Victimization and Offending Behaviors. American Journal of Criminal Justice 46: 882–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, Jorge Arturo, Yolima Bolívar Suárez, Libia Yanelli Yanez Peñuñuri, and Ana Milena Gaviria Gómez. 2021. Validación del Cuestionario de Violencia entre Novios (DVQ-R) para víctimas en jóvenes adultos colombianos y mexicanos. RELIEVE. Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, Ignacio, and Orfelio G. León. 2007. A Guide for Naming Research Studies in Psychology. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 7: 847–62. [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Fernández, Delia, Antonio Daniel García-Rojas, Ángel Hernando Gómez, and Francisco Javier Del Río. 2022. Validación Del Cuestionario De Violencia Digital (Digital Violence Questionnaire, Dvq) En La Pareja Sentimental. RELIEVE. Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Gareth. 1983. Beyond Method: Strategies for Social Research. Beverly Hills: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, Jose, and Eduardo Fonseca-Pedrero. 2017. Construcción De Instrumentos De Medida En Psicología. Madrid: FOCAD. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Rivas, Marina J., Jose Luis Grana, and Ma Pilar Gonzalez. 2011. Abuso Psicológico En Parejas Jóvenes. Psicología Conductual 19: 117. [Google Scholar]

- Paullet, Karen, and Adnan Chawdhry. 2020. Cyberstalking: An Analysis of Students’ Online Activity. International Journal of Cyber Research and Education (IJCRE) 2: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquer Barrachina, Belén, Jesús Castro-Calvo, and Cristina Giménez-García. 2017. Violencia De Parejas Jóvenes a Través De Internet. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.6035/AgoraSalut.2017.4.31 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Rey-Anacona, César Armando, Jorge Arturo Martínez-Gómez, Lizeth Maritza Villate-Hernández, Cindy Patricia González-Blanco, and Diana Carolina Cárdenas-Vallejo. 2014. Evaluación Preliminar De Un Programa Para Parejas No Casadas Que Han Presentado Malos Tratos. Psychologia. Avances de la disciplina 8: 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyns, Bradford W., Billy Henson, and Bonnie S. Fisher. 2011. Being Pursued Online: Applying Cyberlifestyle–Routine Activities Theory to Cyberstalking Victimization. Criminal Justice and Behavior 38: 1149–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyns, Bradford W., Billy Henson, and Bonnie S. Fisher. 2012. Stalking in the Twilight Zone: Extent of Cyberstalking Victimization and Offending among College Students. Deviant Behavior 33: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Salazar, Tania, and Zeyda Rodríguez Morales. 2016. El Amor Y Las Nuevas Tecnologías: Experiencias De Comunicación Y Conflicto. Comunicación y Sociedad 25: 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castro, Yolanda, Rosana Martínez-Román, Patricia Alonso-Ruido, Alba Adá-Lameiras, and María Victoria Carrera-Fernández. 2021. Intimate partner cyberstalking, sexism, pornography, and sexting in adolescents: New challenges for sex education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoker, Melissa, and Evita March. 2017. Predicting Perpetration of Intimate Partner Cyberstalking: Gender and the Dark Tetrad. Computers in Human Behavior 72: 390–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, İbrahim, and Gaye Solmazer. 2022. Perceived partner responsiveness and intimate partner cyberstalking: The mediating role of basic psychological need satisfaction and frustration. Nesne 10: 540–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzberg, Brian H. 2002. In the Shadow of the Stalker. In Law Enforcement, Communication and Community. Edited by Howard Giles. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 112, pp. 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawhun, Jenna, Natasha Adams, and Matthew T. Huss. 2013. The Assessment of Cyberstalking: An Expanded Examination Including Social Networking, Attachment, Jealousy, and Anger in Relation to Violence and Abuse. Violence and Victims 28: 715–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Robert S., and Abel Gustafson. 2014. Seeking Interpersonal Information over the Internet: An Application of the Theory of Motivated Information Management to Internet Use. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 31: 1019–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Baak, Carlijn, and Brittany E. Hayes. 2018. Correlates of Cyberstalking Victimization and Perpetration among College Students. Violence and Victims 33: 1036–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, Andrew, and J. A. Lavoie. 2012. Risky Ebusiness: An Examination of Risk-Taking, Online Disclosiveness, and Cyberstalking Victimization. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 6: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Chanelle, Lorraine Sheridan, and David Garratt-Reed. 2022. What Is Cyberstalking? A Review of Measurements. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP9763–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodlock, Delanie. 2017. The Abuse of Technology in Domestic Violence and Stalking. Violence against Women 23: 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, Joanne D., Jacqueline M. Wheatcroft, Emma Short, and Rhiannon Corcoran. 2017. Victims’ Voices: Understanding the Emotional Impact of Cyberstalking and Individuals’ Coping Responses. Sage Open 7: 2158244017710292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazgan, Çağdaş Ümit. 2022. Investigation of the relationship between online privacy concerns and internet addiction among university students. Medya ve Din Araştırmaları Dergisi 5: 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montero-Fernández, D.; Hernando-Gómez, A.; García-Rojas, A.D.; Del Río Olvera, F.J. Click Surveillance of Your Partner! Digital Violence among University Students in England. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040203

Montero-Fernández D, Hernando-Gómez A, García-Rojas AD, Del Río Olvera FJ. Click Surveillance of Your Partner! Digital Violence among University Students in England. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(4):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040203

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontero-Fernández, Delia, Angel Hernando-Gómez, Antonio Daniel García-Rojas, and Francisco Javier Del Río Olvera. 2023. "Click Surveillance of Your Partner! Digital Violence among University Students in England" Social Sciences 12, no. 4: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040203

APA StyleMontero-Fernández, D., Hernando-Gómez, A., García-Rojas, A. D., & Del Río Olvera, F. J. (2023). Click Surveillance of Your Partner! Digital Violence among University Students in England. Social Sciences, 12(4), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12040203