2. Related Work

Representation is a recurrent theme in the discourse literature, with many works examining the presence and absence of diverse social actors in different discourses. In media discourse, for instance, the diversity and plurality of representations have often been popular points of examination (

Brown et al. 1987). This is primarily because the diversity of media representations can be viewed as a political aim (

Sjøvaag and Pedersen 2019) despite many recent works having argued that such diversity is rarely sufficiently translated into media representations, such as

Kleemans et al. (

2017) and

Ross et al. (

2013). Identity construction is a key issue in representation. Identity, in particular, has been repeatedly examined in discourse studies and is primarily based on the premise that ‘identity is performatively constituted by the very expressions that are said to be its results’ (

Butler 1999, p. 25). This take on identity should highlight the socially constituted and constituting nature of discourse (

Van Dijk 2015), as it simultaneously shapes context while being shaped by it. It also links the current study theoretically to elements of social constructionism since the texts under examination shape the representation of social constructs toward a particular socio–cultural or eco–political issue, which are then transported to the public as they are mediated through the media (

Popa and Gavriliu 2015).

Research on the social construction of gender in discourse studies not only highlights the dynamicity of gender construction but also serves to problematize such a construction. Femininity, in particular, is a rather vague construct with overlapping components, which increase the risk of negative connotations in certain cultural contexts. For example, in a Turkish study, femininity was shown to clash with patriarchal masculinities and blend with other alternative narratives, such as modernization, independence and career success, to achieve respectability and self-value (

Alemdaroglu 2015). This should be understood in light of the inherent connections created locally and regionally between femininity and feminism. Some examinations of feminism, both locally (

Al Maghlouth 2017) and globally (

Brooke 2020), reveal its negative construction, thus problematizing notions such as femininity and feminism to their audience. The problem has been worsened by the varying waves of feminism (

Romano 2021), each of which constructs diverse and loaded ideologies with opposing constructs that potentially contradict local cultural norms. Relevant to this, the recurrent issues of colonized feminism (

Karimullah 2020) and first-world feminism (

Alemdaroglu 2015)—in which stereotypical perceptions of Arab/Muslim women are forcibly cast by Western media discourses to serve colonial agendas—appear too often in the relevant literature so as not to create prejudice against feminism. As a result of such ideological grounding, this study can also be linked to works within critical discourse analysis (CDA). In CDA, the analyst is concerned with the power distribution in discourse (

Van Dijk 2015), and by highlighting areas of unbalance, more awareness is created toward them. While gender asymmetry persists in language, many studies report diachronic changes toward leveling it up. For instance,

Baker and Freebody (

1989) report a negative representation of women in UK textbooks, whereas

Wharton (

2005) reports that while women are still less visible in the reading books in UK schools, they are represented as more capable due to such awareness. All this serves to highlight the potential of CDA in promoting more gender equality.

A recurrent theme in CDA, feminism and feminist discourse research is women’s empowerment, which makes sense since all these enterprises center around power and its unbalanced distribution within any context. Journalism is also drawn to power (

Wolfsfeld and Sheafer 2006), thus making exploring different reconstructions of power and empowerment in media discourse quite tempting for research. A preliminary step is understanding what empowerment is in this particular context. A common thread in the relevant literature (

Elliott 2008;

Kabeer 2005) is that women’s empowerment is fundamentally based on a woman’s ability to exercise choice over her life, especially concerning significant decisions such as marriage, education and work. Choice, in such cases, represents the tangible translation of power possessed by women. However, to validate women’s empowerment, there should be some mechanisms to improve women’s decision-making processes, as well as allow them more access to income, self-confidence and solidarity with other women (

Kabeer 1999;

Mayoux 1998). Thus, on its own, choice is never enough, and it should be paired with awareness, in particular, awareness of possibilities, which is promoted in most pro-women empowerment discourses (

Khumalo et al. 2015). An examination of the research on women’s empowerment reveals strong connections between women’s empowerment on the one hand and access to employment on the other (i.e., feminized labor). Continuing the same line of thought, access to financial freedom and self-independence were prioritized in many works; for instance, in

Termine and Percic (

2015), as critical factors in women’s empowerment and, consequently, in constructing a country’s eco–political discourse (

Sarfo-Kantankah 2021). This explains why, in many corpus studies that examined women’s empowerment within eco–political discourses, terms such as ‘employment’ and ‘work’ were always prioritized as keywords; see, for instance,

Grunenfelder (

2013).

The plethora of research on discourse studies offers a multiplicity of analysis frameworks within gender discourse, most of which center around sexism and gender asymmetry. That being said, the current study adopted a corpus-based approach paired with diverse inspirations from discourse analysis or CDA. This combination is very common, as it allows for an empirical examination of discursive data (

Biber et al. 2012), which, in turn, reduces the chances of subjective interpretations, which are occasionally attached to content-based qualitative works (

Lee 2018). Approaching analysis from such a perspective allows an analyst to uncover hidden ideologies (

Baker 2006) and attempt to impact the values and behaviors of other people (

Partington et al. 2013) while exploring the analyst’s hypotheses in practice (

Baker 2014).

The vast majority of the relevant literature reveals a number of negative constructions of women and gendered discourse across the globe. Some of these corpus studies problematized such negative constructions from a macro lens using corpus methods, for instance,

Almujaiwel (

2017) and

Coimbra-Gomes and Motschenbacher (

2019), while others approached it in a more bottom-up fashion. By utilizing gender-based keywords, such as ‘man’, ‘men’, ‘woman’, ‘women’, ‘girl’ and ‘boy’, these studies examined diverse contexts. Earlier studies from nearly three decades ago (

Kjellmer 1986) documented such negative constructions. Despite some improvement, subsequent works documented relatively parallel portrayals (

Caldas-Coulthard and Moon 2010;

Pearce 2008;

Romaine 1999), be they in academic research discourse (

Brooke 2020;

Grunenfelder 2013), political discourse (

Bakar 2014;

Sarfo-Kantankah 2021), literature discourse (

Eberhardt 2017) or even within discourse attempting to defend and promote women’s empowerment, such as United Nations addresses (

Brun-Mercer 2021).

Saudi Arabia has implemented plenty of transformative measures in the last two decades, which have escalated enormously since the launch of the Saudi 2020 and 2030 visions in 2016. Among its actively progressive missions, it has materialized women’s empowerment plans tremendously in the hope that it can aid in reducing the gender gap from an eco–political perspective. This was translated into the noticeable increase in employment rates of women in male-dominated professions, which began subtly and gradually a little over a decade ago (

Al Maghlouth 2017), yet had perceptibly flourished by the end of the same decade with the rapid increase in female leaders in the country (

Alkhammash and Al-Nofaie 2020). For instance, the Human Resources Development Fund (

HRDF 2023) was founded to publicize and promote Saudi women’s employment in the private sector, along with its other primary motives. By the same token,

Al-Munajjed (

2010) reported in detail how this materialized in reality in recent times.

According to the official annual report issued by the national transformation program (SV2030), a noticeable increase has been detected in the number of working women from 21% in 2017 to 33.5% in 2021. Similarly, the report demonstrates an increase in the economic contributions made by Saudi women from 17% in 2017 to 34.1% in 2021. Along the same line, a parallel increase can also be detected when it comes to women in leading positions from 28.6% in 2017 to 39% in 2021 as a result of some initiatives specifically addressed to equip women with efficient leadership training. The transformation program also released among its plan two initiatives in support of women’s empowerment at work,

Qurrah and

Wusul. The

Qurrah initiative offered subsidized childcare to working mothers, reaching a total of more than 6645 female beneficiaries by the end of 2021.

Wusul, on the other hand, offered subsidized transportation to more than 112,160 female beneficiaries. Due to such reforms, the change in women’s representation within socio–cultural and eco–political domains was inevitable. Consequently, all of this attracted media attention globally (

Elyas and Aljabri 2020), thus further highlighting the need to explore Saudi women’s constructions on media platforms.

Deconstructing the portrayals of Saudi women should acknowledge the multiplicity of their identity to maximize the potential of the analysis. Ethnically, ideationally and regionally, Saudi women can be simultaneously constructed within broader definitions as Arab and Muslim women in addition to their national identity. Unfortunately, most of the relevant literature portrays negative constructions when it comes to the construction of Arab and Muslim women. To name but a few,

Al-Hejin (

2015),

Karimullah (

2020),

Ruby (

2013) and

Saleh (

2016) all reported negative constructions in which these women were constructed as submissive, passive, oppressed, subordinate and in need of help, often from Western agents. Such portrayals were consistent with a neo-orientalist construction of women (

Saleh 2016), victimizing Arab/Muslim women and casting them as third-world women who should be urgently saved (

Kahf 1999) to serve post-colonial interventionist agendas (

Saleh 2016).

Comparably, constructions of Saudi women as a nationality reveal similar patterns, especially with analyses of English language media sources published in the internationally available literature. For instance, in his corpus-based analysis of Saudi women in BBC coverage,

Al-Hejin (

2015) documented a negative construction of the hijab (head veil in Islam) as an obstacle to the progress of Saudi women, citing examples in which refusing to wear the hijab was associated with successful businesswomen and female leaders. Similarly, in other media discourse analyses,

Bashatah (

2017) and

Elyas and Aljabri (

2020) revealed framing patterns within Western newspapers through which Saudi women were negatively constructed. In addition to this,

Karimullah (

2020) reported contrasting findings within a self-built corpus between Saudi women on the one hand and Kurdish or Tunisian women on the other. In this corpus, Saudi women were cast as oppressed and non-agents, along with women in conflict regions, such as Yemen and Afghanistan, while Kurdish and Tunisian women were rather portrayed as active and idealized with empowered constructions of feminine agency. Interestingly,

Mishra (

2007) conducted a comparative study of American and Saudi newspapers, which revealed that Saudi women were portrayed along the same negative lines of passivation and oppression identified earlier in American newspapers, while American women were, in return, portrayed as superficial and immoral in the Saudi press. However, these same Saudi platforms reported rather positive and active constructions of Saudi women who were in charge of rejecting Westernization and maintaining their moral purity. The same positive and active thread of construction of Saudi women was also reported in another discourse analysis of Saudi newspapers (

Elyas et al. 2021).

As is evident in this concise review, the vast majority of gender studies in media discourses were based on English data and/or data from the Western media, especially those with a corpus-based design (

Sarfo-Kantankah 2021). This demonstrates the gap in the discourse literature in terms of targeting gender constructions in other languages, such as Arabic, in its investigations. Keeping in mind the scarcity of relevant research from Arabic corpora, the current study attempted to shed light on this gap in the hope that it adds to the growing research and helps to even out gender asymmetry in media discourse. It also attempts to promote awareness of this issue and explore whether the recent social and eco–political transformations in Saudi Arabia were mirrored in this discourse.

Such an urgent need stems from an understanding of the theoretical underpinning of the intricate relationship between discourse on the one hand and context on the other. This emerges as a fundamental theme in discourse studies under the premise that a mutually constituting relationship between these two exists (

Fairclough and Wodak 1997) too often not to be missed. In particular, this could be linked to the theory of social constructionism and its emphasis on the role of communication in reality construction. To illustrate, such theorization highlights the discursive potential of linguistic construction in shaping social and cognitive constructs as well as their reciprocal status as a dynamic product of the same constructs (

Van Dijk 2015). This, for instance, has been pointed out in the aforementioned comparison of women’s representation in UK textbooks (in

Baker and Freebody 1989 versus

Wharton 2005). If it was not for the potential of such discourse analyses, these improvements could not have been made and consequently exposed and distributed among students.

Examining linguistic manifestations within discourse in search of evidence of social change utilizing a variety of semiotic parameters is a common practice in support of what is often classified as positive discourse analysis (

Al Maghlouth 2017). According to

Martin (

2004), positive discourse analysis does not diverge from works within CDA but rather complements them. In particular, it seeks to embody evidence of resistance to the biased status quo through diverse linguistic tools (more on this in

Section 3). In light of this, the main research question in the current study was as follows: to what extent do co-occurrences (collocate + central word) and their broad contexts indicate the discursive and social practices of the women-related themes that were introduced, promoted, or modified over the two years and the multiple sections? The answer to this question is provided in the results section. We arrived at the answer using prominent computational techniques that tested the study data retrieved from the Saudi newspaper archive for the years 2021 and 2022 and provided the distributions and dispersions of the central word and their collocations in a 2n-gram span from the 2021 and 2022 Saudi newspapers and across the seven sections of the newspapers’ structure (front page, economy, international, sports, society, culture and religion). Further computational techniques were also adopted to show the amount of variance between the sample data from the two years using dispersion measures.

3. Data and Computational Techniques for Corpus Analysis

The data we collected represented two months from each of the years 2021 and 2022. The data used in this paper were crawled from the Saudi archived newspapers website

www.sauress.com (accessed on 1 December 2022), and we assigned two months from each year, due largely to these being the two months in which the intended central word as the nodes المرأة (woman) and النساء (women) appeared more frequently. This was detected using an advanced search we conducted on the website itself. Thus, our sample was from February and March for the year 2021, and from January and February for the year 2022. The Saudi archived newspapers included 43 local newspapers. This archived platform publishes daily news and articles, which helped with the task of simultaneous crawling and structuring.

The relevant literature proposes many linguistic manifestations to underpin the intricate interplay between discourse on the one hand and gender representations on the other; to name a few: semantic macro structures (

Al-Hejin 2015), metaphor analysis (

Al Maghlouth 2021), titles, (

Alkhammash and Al-Nofaie 2020) social actor representation (

Almaghlouth 2022), multimodality (

Alkhammash 2022) and process type analysis (

Koller 2012). The current study was designed based on minute examination of collocations. Collocations are pairs or groups of words that often come together within the same near-linguistic context (

Baker 2006). Due to such linguistic proximity, collocations are often examined as evidence of

Moscovici’s (

2000) mental representations since their co-occurrence often suggests that they tend to correlate in cognition as well. Against this backdrop, it is hypothesized in the current study that the aforementioned measures taken by the Saudi government in support of women’s empowerment can be traced back to the newspapers’ corpus at hand in the form of more empowered/positive women’s representations. In that sense, utilizing collocations as an inbuilt tool in corpus processing has been quite informative within many gender studies (see, for instance,

Almujaiwel (

2017), within a gender-based Saudi context). The reviewed literature, especially from non-Saudi newspapers, has confirmed the negative representations attached to Saudi women within such discourse. By investigating the collocational behaviors of the intended central words, this study might be able to detect a corresponding linguistic change of such representations, especially keeping in mind the reformative changes made in support of more women’s empowerment.

As the focus of our analysis was on the collocational behaviors of the intended central word:

woman (and its plural form:

women), in the sections of the newspaper structures, information regarding the number of texts in each local newspaper was unnecessary. According to our linguistic raw data,

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the number of texts (files), each of which contained a specific article, and the number of types (unique word forms) and tokens (all running words) across the respective years. The tables show the numbers of texts, types and tokens in the seven sections.

The computational techniques adopted for the corpus/data analysis were as follows: first, the raw and normalized frequency analysis of the central word between the two years; second, the raw and normalized frequency analysis of the intended lexical bundles (5n-grams collocation window) between the two years; third, the raw and normalized frequency analysis of the intended lexical bundles between the two years and the newspaper section data; and fourth, the raw and normalized frequency analysis of the central word between the multiple newspaper sections data. The terms and their concepts needed to be well-defined for the sake of clarity. Such clarity paved the way for explaining the computational techniques used for our data analysis. These statistical corpus linguistics terms were analyzed in terms of the normalized frequency—corpus size

n, relative frequency

rf and normalization base

nf (

McEnery and Hardie 2012, pp. 50–51)—and dispersion—the standard deviation SD, coefficient of variance

CV and Juilland’s

D (

Brezina 2018, pp. 46–53).

The corpus size n is the total number of all running tokens/words in a given corpus. The raw frequency f of a word is the absolute number of f in a given corpus. The relative frequency rf is the number of times a word occurs divided by n. The normalized frequency nf is simply the result of . The normalization base nf is a number to be set on average, and they always follow a numerical pattern that starts with 1 followed by zeros. For example, if n equals any number in a format of tens of thousands (27,000, 76,938, 89,002 and so on), the nf will be set to the base 10,000 or less (1000 or 100) according to the preference of the human analyst. The corpus-to-corpus ratio (nf1/nf2) is computed to provide the number of times the word occurs in a corpus compared with another corpus. It gives the difference ratio between the nf over the multiple corpora or sub-corpora. The benefit of using the nf measure is to avoid the unevenly distributed number of f for a given word while its nf is low. For example, in our data, the f values for the central words woman and women between the culture and religion sections for the sample of the year 2021 were 220,740 and 79,510, respectively, but the nf (×10,000) values were 6.025 and 8.427, which means that the nf in the religion section was more than that in the culture section.

Dispersion is different and more accurate than distribution when it comes to the whole corpus. The parts of a given corpus are simply the nf (normalization base). Distribution is usually lacking in denseness, while dispersion tells us how the relative frequencies of a word’s per normalization base (×100, ×1000, ×10,000 and so on) are agglomerated between the parts of the intended corpus and on the whole. The merit of dispersion is that it is a set of measures that output the variation within different parts of the corpus. The measures utilized are the coefficient of variance CV and Juilland’s D. The coefficient of variation CV is simply calculated as follows: . The result of CV is then divided by the square root of the number of parts minus 1: . The final result comes out between 0 and 1. When the CV is closer to 0, the given word is more evenly distributed throughout the parts of the corpus. As for Juilland’s D, it is a measure that depends on CV and is based on the following formula: . The result of Juilland’s D is also between 0 and 1. When it is close to 1, the distribution of the given word is perfect over the parts of the corpus. This means that CV and Juilland’s D are opposite in terms of reporting a perfectly or imperfectly even distribution.

5. Discussion

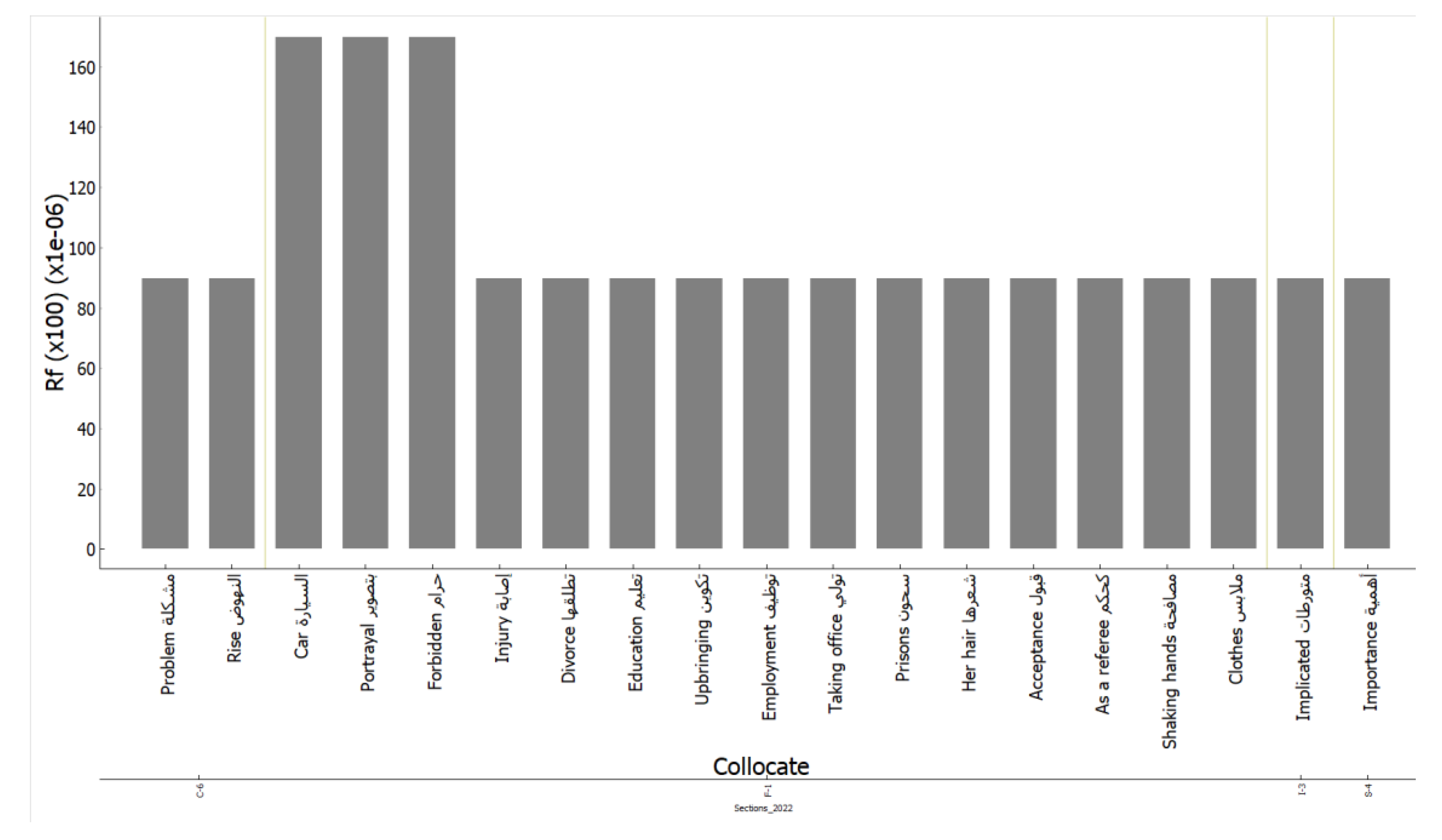

All the observable facts about the normalized frequencies

nf (relative frequencies

rf × 100) of the co-occurrences of the central word from the data parts of the 2021 and 2022 samples and about the dispersion measures gave us grounds to look through the citations/examples of the co-occurrences. The next step was to capture the broad contexts of the collocations in their given citations to categorize the discursive practices. In

Table 12,

Table 13 and

Table 14, we numbered the collocates associated with the central word and provided the broad context constructs and the contextualized co-occurrences. The quantitative method relating to the measuring of the normalized frequency base of the co-occurrences was used to express the frequencies of the co-occurrences relative to all the study data. This method is powerful as it is based on the average. In addition, such computational techniques utilized for text data are of high importance in discourse analyses, especially critical discourse analysis (CDA), since the media and newspapers have become digitized. The technique of scraping textual data and organizing it in terms of metadata is feasible using different techniques and the library

request in Python. Moreover, the

nf and dispersion measures that tackle the unbalanced linguistic data parts provided us with the confidence to analyze and report the progress of women’s empowerment in Saudi newspapers after Saudi Vision 2020.

Recall that the study question was the following: to what extent do co-occurrences (collocate + central word) and their broad contexts indicate the discursive and social practices of the women-related themes that were introduced, promoted or modified over the two years and the multiple sections? The findings given in

Table 12,

Table 13 and

Table 14 included all the examples and their broad contexts with reference to their sections. The number of cases in which the progress of women’s empowerment was supported was 74. On the other hand, progress was impeded in only 17 cases. Therefore, opponents were far fewer in number than supporters. Opponents were found in the

international,

culture,

society and

religion (

Table 12),

front page and

religion (

Table 13) and

economy sections in the year 2021, and the

international,

society,

religion and

front page sections in both years (

Table 14).

In light of this, the quantitative findings could be taken as empirical evidence of the reciprocal and constructionist link between discourse and context that was established earlier in this paper and is often highlighted in the relevant literature. In particular, what can be inferred from the above discussion is that the reformative measures taken by the Saudi government in accordance with its 2020 and, prospectively, 2030 visions are starting to materialize within discursive practices at various levels. This has not only taken place as these changes have been gradually implemented but has also manifested at a linguistic level through the national media. Women’s empowerment emerges within this context as a dominant theme that extends across various fields, and opposition to this theme, which used to be quite strong in previous decades, is starting to fade.

In that sense, it is possible to see the link between our results and what

Fairclough (

1992, p. 201) refers to as the ‘democratization’ and ‘technologisation’ of discourse. Democratization of discourse can be defined as ‘the removal of inequalities and asymmetries in the discursive and linguistic rights, obligations and prestige of groups of people’, while technologization refers to the opposite in which there is a deliberate or subconscious intervention in discourse to maintain status quo by ensuring that a given discursive hegemony is discursively introduced and distributed. As many of the examined collocations established a shift toward more positive and women-empowering representations—be it through the positive polarity of the noun collocates or the grammatically active verb collocates—some of the linguistic asymmetries disfavoring women are also starting to decline.

Taking into consideration the aforementioned discussion of positive discourse analysis and the socially constituting inherent feature of discourse, one might be able to highlight the potential of such linguistic transformation in pushing forward more gender equality. Since it has been established in the analysis that such reformative measures were correspondingly translated in linguistic circles, it is only fair to predict further social change to be initiated by discourse on its linguistic end. In particular, this should be seen as operating in a circular fashion rather than a linear one. As change is repeatedly introduced and distributed discursively vis-à-vis the status quo within a particular context, it begins to transform gradually into the status quo per se (

Al Maghlouth 2017). This usually takes place through several means, one of which is the normalization of such change linguistically and, in consequence, cognitively and socially.

This could be also linked to the role of governing and policymaking as primarily societal factors within a given discourse, as proposed by

Bracher (

1993, p. 53). By the same token and drawing on Gramsci’s structure of power,

Fairclough (

2013) highlighted the significant role of political power in the domination of certain ideologies, which would gradually inform and be informed by discourse

Fairclough (

2013) highlighted the significant role of political power in the domination of certain ideologies, which would gradually inform and be informed by discourse. This is consistent with what was highlighted in another local study (

Al Maghlouth 2017), in which social change was advocated for and pushed forward by decision makers and the associated policy in the country. Interestingly, in her study, policies in support of women’s empowerment faced opposition more than a decade ago; nevertheless, they persisted and paved the way for far more reformative measures to materialize. However, this documented far less opposition, which is a finding that highlights the role of awareness in promoting, accepting and maintaining the desired change alongside governing and policymaking.

Moreover, our study data add to the rich research on the

us–them representation spectrum, which is a recurrent theme in social psychology. In particular, a detailed examination of the relevant literature clearly documented a distinction between how Saudi women are constructed by the Saudi media locally and how they are portrayed on a more international level by the foreign media. For instance, othering and negative representations in the Western media often seem to be reinforced (

Al-Hejin 2015;

Elyas and Aljabri 2020;

Karimullah 2020;

Ruby 2013;

Saleh 2016) and sincere changes or reforms in support of women are often overlooked. However, media sources produced, distributed and examined locally appear to be more consistent at reporting such changes and even portraying a more progressive construction of Saudi women. This should be approached from a perspective that validates such findings while acknowledging that this might not always be the case. To elaborate on this,

Ndambuki and Janks (

2010), for instance, reported a linguistic clash between how Kenyan women are portrayed discursively as lacking in agency by Kenyan political leaders, while in reality, these women were quite agentive despite being surrounded by dominating discourses of patriarchy and rurality in Kenya. What this signifies is that the constructionist link between discourse and context in this Kenyan study was not analyzed based on broad discursive patterns of varying representative data, and thus, such a link should not be taken for granted across different discourses and contexts.