Abstract

In recent years, there has been an increasing visibility of intersex people’s issues and experiences of human rights violations amongst international human rights institutions and monitoring bodies. At the United Nations, to date, there are more than 500 treaty bodies’ concluding observations taking notice of human rights abuses against intersex persons and calling member states to fulfil their human rights obligations. This paper follows the inclusion and visibility of intersex issues in the text of the United Nations treaty bodies’ concluding observations. I looked for explicit mentions of the word “intersex” in treaty bodies’ report documents and reviewed how the concluding observations and recommendations of these bodies resonate with demands coming from intersex activist groups. I found that the main issues included in the treaty bodies’ reports concern intersex genital surgeries (IGS), autonomy claims, and demands for redress and support mechanisms, and while these issues have gained visibility, there are also a number of demands by intersex activists that remain less visible, if not invisible altogether. This paper aims at providing evidence of the increasing visibility and awareness of human rights monitoring bodies have over intersex people’s rights.

1. Introduction

‘Intersex’ is an umbrella term used in activist and human rights circles to describe “a wide range of innate bodily variations in sexual characteristics. ‘Intersex’ people are born with sex characteristics that do not fit typical definitions of male or female bodies, including sexual anatomy, reproductive organs, hormonal patterns, and/or chromosomal patterns” (United Nations 2019, p. 2).

Throughout Europe and around the world, intersex people face a wide range of human rights violations based on different variations of their sex characteristics, and are subject to stigma, misrecognition, pathologisation, violence (including medical violence), and degrading, humiliating, and inhuman treatments (CoE 2015; IACHR 2015; United Nations 2019). Likewise, intersex persons are exposed to different forms of discrimination that they experience through their life cycles, for example, in healthcare, education, or employment settings, among others (Carpenter 2016; Bauer et al. 2020; Travis 2015). One of the main concerns of intersex activists and civil society organisations (CSOs) continues to be surgical interventions performed during childhood (including to newborns) with the aim of ‘normalising’ intersex bodies to fit the socially and medically accepted male/female binaries (Bauer et al. 2020). These surgeries are often framed by activists as forms of mutilation and/or torture or ‘intersex genital mutilation’ (IGM)1. In this paper, the term ‘Intersex genital surgery’ (IGS) is used, as the term IGM does not seem to be widely adopted by UN treaty bodies that continue to call, however, member states to put a stop to ‘surgeries and treatments’ that go against human rights standards. Regarding the European region, according to the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), ‘normalisation’ surgeries are carried out on intersex children in at least 21 member states of the European Union (EU) (FRA 2015). Among the member states of the EU and the Council of Europe (Coe), only five countries (Malta, Portugal, Iceland, Germany, Greece) have legislation that provide some form of protection against these types of interventions during early childhood.2

In recent years, intersex activist movements have turned to the international fora and institutions to expose their needs and human rights demands, and arguably, these institutions have started to listen and increase visibility of the human rights demands of intersex people (Bauer et al. 2020; Ammaturo 2016; Rubin 2015). However, little attention has been given in the field of intersex studies and social movements to activist groups’ interactions with international human rights bodies and their efforts to raise awareness and visibility of their cause. A notable exception is the work of Saskia Ravesloot (2021), who has followed the inclusion of intersex issues in the recommendations of the Human Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review, looking specifically at the nature, content, and framing of such recommendations. More recently, Garland et al. (2022) also analysed the barriers and challenges in transposing international recommendations into domestic change. My research aims to expand the current literature on intersex activist groups’ engagements with international institutions and supplement existing gaps concerning UN treaty bodies.

My goal is providing empirical evidence of the growing visibility and acceptability intersex activists’ concerns are getting amongst international human rights mechanisms such as the UN treaty bodies, with the aim of showing that activists’ claims are supported by experts in the field of human rights with specific mandates to overview states’ compliance with international obligations. My findings indicate that there has been an increasing visibility or intersex concerns since 2009 and that main human rights’ visible demands focus on intersex genital surgery; autonomy and bodily integrity; and redress and reparations concerns, claims that align with those demands coming from activist groups.

For this research piece I followed the inclusion and visibility of intersex issues in the text of the United Nations distinct treaty bodies’ (UN TBs) concluding observations and recommendations. Three main questions guide this research: (1) To what extent are intersex issues made visible through UN TBs recommendations and concluding observations? (2) How are treaty bodies’ recommendations shaped by activist groups demands? (3) How is intersex genital surgery understood and framed as a human rights problem by treaty bodies? To analyse these questions, I conducted a content analysis of the UN treaty bodies’ concluding observations reports that include mentions of the word intersex. I reviewed the UN Human Rights Index for mentions of ‘intersex’ and ‘intersexuality’ because research suggests these terms are widely used by activists and human rights bodies (Lundberg et al. 2018; Monro et al. 2019; Reis 2007; Jones 2018; Dreger and Herndon 2009) up to June 2021 and disaggregated the data pertaining to the nine core treaty bodies’ concluding observations reports. This query resulted in 495 global mentions of the word intersex in the body of 230 concluding observation reports. Later, I did a second search and applied other terms used by activists, academics, and medical practitioners such as ‘disorders of sex development’, ‘differences of sex development’, and ‘sex characteristics’. The second search did not alter the results from the first search.

This paper is structured as follows I start with a general overview and introduction to intersex activism and present evidence for its increasing internationalisation, which supports my argument about increasing visibility in transnational settings. Second, I provide a background information on treaty bodies, their functioning, and the different ways in which social movements and activist groups carry out advocacy and lobbying efforts with these and other human rights monitoring bodies. Third, I describe the methodology I used for tracking explicit references or mentions of intersex issues in treaty bodies’ reports and present my findings via a content analysis. Fourth, I explore in depth the way intersex genital surgery is framed by the different UN treaty bodies as a human rights violation, considering legal and activist arguments in my analysis. Because of the large data set of information found globally, in this paper I limit most of my findings to the European region, as this is also the continent that has received the largest number of concluding observations and recommendations by treaty bodies.

2. The Internationalisation of Intersex Activism

Intersex activism has been around since the early 1990s (Dreger and Herndon 2009; Bauer et al. 2020) and compared to other social movements, such as feminist or LGBT collectives, intersex collectives and activist groups are relatively small. Over the last decade, however, there has been an internationalisation of intersex activism, with the creation of regional and international networks and organisations. These networks provide a forum for interaction, strategizing and advocacy for the rights and political goals of this movement at the regional and global levels (Rubin 2015; Carpenter 2016). Over the last 15 years, international networks of intersex activists have increasingly advocated the use of human rights discourses and legal frameworks to shape their demands and voice their concerns, most notably their opposition to intersex ‘normalising’ surgeries (Bauer et al. 2020; Ammaturo 2016; Winter Pereira 2022).

After I conducted a rapid review of activist websites, press releases, public statements, reports, and lawsuit documents, the prevalence of human rights discourses and framings was evident. This was also noted by scholarship that has observed the increased number of direct advocacy opportunities with different human rights monitoring bodies (HRMB), such as the special procedures of the United Nations, the Human Rights Council, and the UN treaty bodies, the Council of Europe (CoE) and certain agencies and bodies of the European Union (Bauer et al. 2020). The literature also shows that these HRMBs are beginning to pay attention and listen to the demands of intersex activists (Bauer et al. 2020; Crocetti et al. 2020; Ammaturo 2016; Suess Schwend 2018). Some HRMBs have responded to these demands with a series of observations and recommendations aimed at ensuring the rights of intersex people at the State level, reminding the States of their obligations under international human rights standards they have adopted (Ghattas 2019; Bauer et al. 2020; European Parliament 2019; PACE 2017; CoE 2015; FRA 2015; United Nations 2019).

There is plenty of scholarship on how social movements and activist groups engage with international human rights institutions, notably the United Nations, with the aim of influencing international and domestic policy and moving their political goals forward. Gaer (2003), for instance, has noted the historical increase of civil society participation within the UN institutions, and particularly the importance of civil society group engagements for the functioning of the UN treaty bodies. Johnstone (2006) has written about feminist groups’ engagements with international law and UN institutions with the aim of advancing gender mainstreaming goals. Joachim’s (2003) work on feminist movements’ investments with the United Nations’ agenda reflects on framing processes to recognise violence against women and sexual and reproductive health as human rights issues, whether these were previously not only obscured from the UN political agenda but also not associated with human rights framings.

In the field of LGBT and queer politics and activism, Vance and colleagues’ work (Vance et al. 2018) explore the ‘rise’ of LGBT issues amongst United Nations institutions as well as the framing of LGBT rights as human rights. Similarly, D’Amico (2015) observed the interactions between political opportunities structures, collective action framing processes, and resource mobilisation with the successful inclusion of LGBT issues within the UN agenda. Another valuable contribution is that of Mulé’s work (Mulé 2018), which extensively describes the personal experiences of LGBT identifying activists when engaging with the United Nations, as well as strategies for navigating the rise of counternarratives. These are just some examples of how different groups and social movements have taken a strategic turn to engage with institutions such as the United Nations to amplify their demands.

The different forms in which activists and NGOs engage with international bodies in hopes of creating or igniting change at the local level is the matter of study of what is known as the ´boomerang effect´ in social movements, international relations and international politics studies (Keck and Sikkink 2018; Waites 2019; Allendoerfer et al. 2020). As Dondoli (2015) notes, civil society engagements with human rights bodies take different shapes and forms. NGOs and activists lobby governments and politicians to ratify human rights treaties that make states subjects of international monitoring and accountability, activists then gather information regarding human rights violations and inform monitoring bodies. Some activists also support and talk to victims, submit reports to monitoring bodies and national human rights institutions, propose appropriate language and terminologies for law and policy making, participate as observers in public sessions, provide expert knowledge in private meetings, and propose new and innovative ways to understand and frame human rights. Furthermore, activist groups follow up on resolutions and recommendations of monitoring institutions and hold the state accountable for its actions and international commitments made, and then they do it again once a reporting cycle restarts (Dondoli 2015).

Like feminists, LGBT groups, and many others, international intersex activist organisations and networks of organisations also engage in these practices (Garland et al. 2022; Winter Pereira 2022). Groups such as OII Europe, Intersex Human Rights Australia (IHRA), Zwischengeschlecht (Stop IGM), and the NNID Foundation (NNID, Netherlands organisation for sex diversity) often participate in meetings, compile information on human rights violations, and submit information and reports to different human rights monitoring bodies, notably the UN treaty bodies, whenever there is a reporting period.3 Zwischengeschlecht, for example, collaborates with local organisations that may have less experience working in transnational global settings or may not be familiar with the UN or specific mechanisms to submit NGO (shadow) reports to treaty bodies and committee members (Winter Pereira 2022).

These different forms of engagement have often turned fruitful. At the United Nations, intersex issues have been mentioned at Human Rights Council’s universal periodic review (UPR) since 2011 and have since added up more than 600 UPR recommendations that broadly mention intersex people and call upon member states to protect the rights of this group of people (Ravesloot 2021). Likewise, to date, there are more than 500 treaty bodies’ concluding observations calling member states to fulfil their human rights obligations as they specifically pertain to intersex people. To date, OII Europe has monitored that no less than 74 shadow reports have been submitted to UN TBs by civil society organisations specifically talking about the situation of intersex people’s rights.4 These reports not only provide committee members with the most up to date information but also follow up on the best (or worst) practices of States and give proposals for recommendations, which, if accepted by committee members, will translate into official policy recommendations given by the treaty monitoring body to the state, not just the government in turn or the executive branch, but the state as a subject of international law.

3. Looking for Signs of Intersex Visibility Within the United Nations: Research Methodology, Analysis, and Findings

The main motivation behind my research is to bring attention to the fact that UN TBs are increasingly paying attention to intersex human rights issues and, in doing so, show that activists’ claims are supported by experts in the field of human rights with specific mandates to overview states’ compliance with international obligations.

Within the universal system of human rights, treaty bodies are committees with the legal mandate to monitor state governments’ implementation of their obligations under specific human rights treaties. International practice recognises the existence of nine human rights ‘core’ treaties (or conventions)5 and ten monitoring bodies.6 The treaty bodies are “committees of independent experts whose mandate emanates from the nine core international human rights treaties” (United Nations 2017, p. 2). These experts have the task to monitor the state parties’ human rights obligations under their respective treaty (Collister et al. 2015; Mechlem 2009; O’Flaherty 2006).

All treaty bodies, except for the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture (SPT), receive and consider reports submitted by state parties on the implementation of their specific mandate treaty and issue concluding observations, which include a series of recommendations to guide states in the better fulfilment of their international obligations. These general comments and recommendations are interpretations of specific substantive or procedural provisions of their respective treaties and/or address relevant issues pertaining to their mandate treaty (Collister et al. 2015; United Nations 2017). Some treaty bodies may have the mandate to consider individual communications and inter-state complaints, to initiate inquiries, or carry out investigations through country visits (Collister et al. 2015; United Nations 2017). The way these tasks are carried out is based and described in their mandate treaty. As stated by the International Service for Human Rights (ISHR), an NGO specialised in training human rights defenders for working with UN institutions, “The main purpose of the reporting process is for the treaty bodies to examine the level of the state’s implementation of its obligations under the treaties” (Collister et al. 2015, p. 14).

With the purpose of exploring how treaty bodies recalled intersex issues in the text of their reporting documents, I conducted a content analysis of the UN treaty bodies concluding observation reports that include mentions of the word intersex. I reviewed the UN Human Rights Index for mentions of ‘intersex’, ‘intersexuality’, ‘disorders of sex development’, ‘differences of sex development’, and ‘sex characteristics’ until the end of June 2021 and disaggregated the data pertaining to the nine core treaty bodies concluding observations reports. I excluded the SPT because of significant differences on how this particular body carries out its reporting and deleted duplicated results. This query resulted in 495 global mentions of the word intersex in the body of 230 concluding observation reports (see: Table 1).

Table 1.

Global mentions of intersex issues segregated into reports, concluding observations (cobs), and recommendations (recs).

Interestingly, the query showed zero mentions of the medical term ‘Disorders of sex development’ (DSD) coming from the UN treaty bodies, except for a recommendation made to Denmark, in which the CESCR committee asks the state to “Replace in its legislation the concept of ‘disorders (differences) of sex development’ with a definition of intersex person in which differences in sex characteristics include genitals, gonads and chromosome patterns”.7 The DSD term was originally adopted in 2006 by a group of specialised medical practitioners and has since become popular in the medical community to refer to people with uncommon sex traits and characteristics (Lee et al. 2016; Hughes et al. 2006). However, it has been rejected by human rights advocates and intersex activists as they consider it pathologizing, with one of the reasons being that it locates power/knowledge primarily in the medical community rather than in people with lived experience (Davis 2014; Garland et al. 2022). This is an interesting finding that could indicate the medicalised DSD terminology is a language that is rejected also in the ambit of the United Nations. The term ‘differences of sex development’ is also mostly absent from the treaty bodies’ reports, with the only mention being the case of the recommendation made to Denmark mentioned above. ‘sex characteristics’ is also a term that has not been yet widely adopted by the UN treaty bodies, having only found 9 mentions from 8 report documents.

To look at intersex visibility from a comparative perspective, the tables below show how ‘intersex’ mentions in the TBs’ report documents compared to other groups of people or issues. These numbers would suggest that while intersex is not as widely mentioned or visible as references to gay people or issues such as HIV, for example, it does have the same kind of visibility as groups such as transgender women8 or issues such as female genital mutilation (see: Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Mentions of ‘intersex’ compared to other selected groups in TBs’ reports.

Table 3.

Mentions of ‘intersex’ compared to other selected issues in TBs’ reports.

Because mentions in UN TBs’ documents do not necessarily translate into substantive recognition of rights, I examined the way in which these references were made. I analysed if these references were recommendations given to states for law and/or policy change or merely noted observations. I also examined which TBs are giving visibility to intersex groups’ concerns, which regions have received most recommendations, and which issues or concerns coming from activist groups are getting the attention of UN TBs. To limit the scope of my analysis, I focused it on the European region.

4. Content Analysis

4.1. Concluding Observations and Recommendations Concerning Intersex People

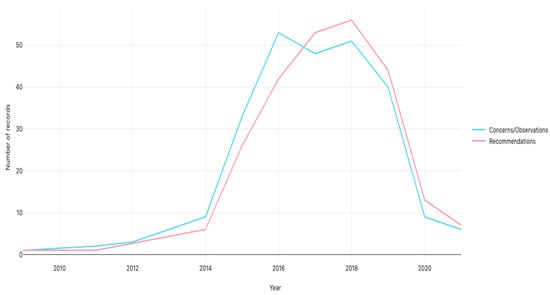

To start my analysis, I segregated mentions of the word ‘intersex’ into observations (n = 252) and recommendations (n = 244). This distinction is made on the basis that treaty bodies’ observations can note progress or specific situations the UN TB wants to highlight, and observations can also note concerns or pressing situations of worry. Recommendations, on the other hand, explicitly call for state governments’ action. After analysing the data concerning observations/recommendations and taking time as a factor, an interesting finding was that there seemed to be an increase in references to intersex issues and intersexuality by TBs until 2017, when there was a record number of 57 references that year alone supporting the claim that intersex visibility is increasing. Since 2018, however, there seems to be a decrease of intersex references in TBs’ reports. From 2019 onwards the impact of COVID may have had a role to play, however further research outside of the scope of this paper needs to be done as to investigate why the decrease has occurred (see: Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Global mentions of intersex issues segregated into recommendations and concerns/observations.

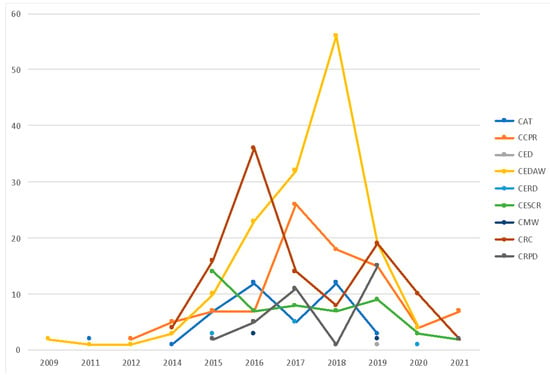

4.1.1. Which Treaty Bodies Are Giving Visibility to Intersex Issues?

I also segregated the data by the different treaty bodies to explore which venue seemed more ‘open’ to hearing intersex activists’ demands or shedding a light on intersex issues. In this case, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW committee) appeared to be the one body with the highest number of references to ‘intersex persons’ on a global scale, and it was also the TB that made the first ever intersex recommendation back in 2009 (see: Table 4 and Figure 2).

Table 4.

Mentions of intersex issues segregated by issuing treaty body.

Figure 2.

Global mentions of intersex issues by treaty bodies considering time as a factor.

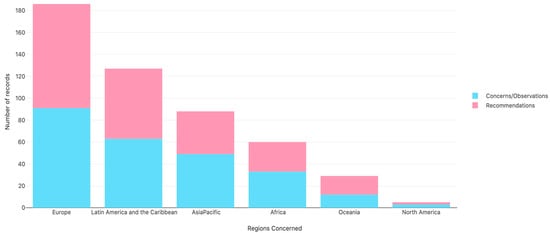

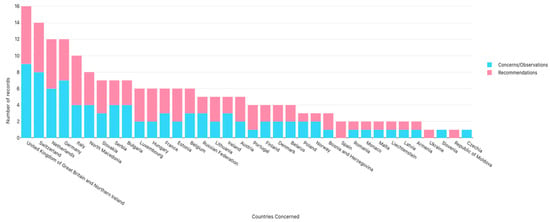

4.1.2. Visibility by Regions

Because of the large number of global references to intersex issues (n 495), I decided to reduce the data analysed by segregating it by region and limit the second part of my analysis to one specific region. Europe was selected as is the region with the largest number of recommendations and concluding observations, a total of 186 references to intersex issues within 87 unique treaty bodies’ reports.10 I also decided to focus on recommendations as they invite for state action, which, in the case of Europe, amounts to 95 recommendations present in 73 TBs’ reports. In this sense, subsequent data in this paper analyses European recommendations unless stated otherwise (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Number of treaty bodies’ observations and recommendations segregated by regions.

Figure 4.

Number of treaty bodies’ observations and recommendations for European countries.

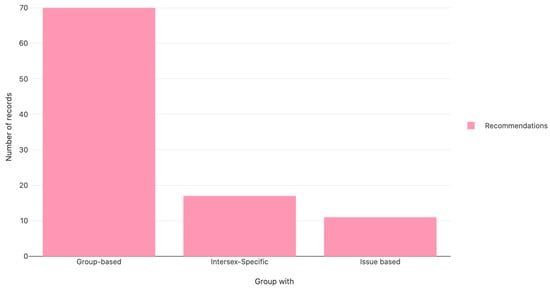

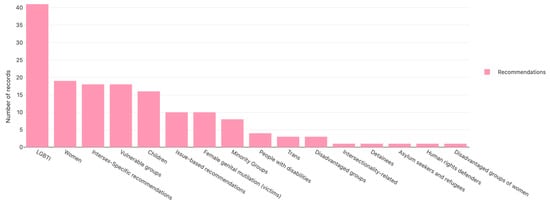

4.1.3. Visible as an Intersex Specific Issue or Grouped Together with Others?

Intersex activist groups and intersex related scholarship have expressed concerns over the risk of intersex-specific issues and demands being diluted, that is, made less visible or left behind when grouped together within the umbrella acronym ‘LGBTI’ (Jones 2018; Bauer et al. 2020), particularly those claims related to intersex genital surgery, sex characteristics, and bodily integrity. For instance, when analysing the results of the UK’s LGBT 2017 survey, Garland and Travis (2020b) note the limitation in responses specific to intersex people or intersex issues, as the survey was primarily targeted towards the LGBT community (and framed as such). Because of these concerns of conflation, another aspect that I examined was if intersex issues were considered by TBs as specific or standalone issues (e.g., ‘intersexuality’) or as issues pertaining to intersex people as a specific group (e.g., ‘intersex persons’, ‘intersex children’) or, on the contrary, if issues were considered in conjunction with other groups (e.g., ‘LGBTI’, ‘vulnerable groups’) (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Number of TBs’ recommendations only for European countries segregated in group-based, issue-specific, or intersex-specific recommendations.

When recommendations were found under the section ‘intersexuality’, ‘intersex persons’, or similar, these were coded as intersex-specific recommendations; on the contrary, if intersex people were considered or mentioned as part of a larger group of persons, the recommendations were coded group-based. This information was coded and verified by looking at both the text of the report document and the section in which the recommendations were situated in the report. A third type of recommendations emerged and were coded as ‘issue-based’ recommendations, which are documents that do not focus on groups but rather particular issues (e.g., non-discrimination as opposed to ‘LGBTI discrimination’ or the ‘right to health’, ‘harmful practices’, amongst others) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Number of TBs’ recommendations only for European countries segregated into groups or themes that intersex people were frequently associated with.

The analysis showed that most of the recommendations coming from treaty bodies are group-based and, in this same line, most mentions of intersex issues are associated with LGBTI people. Other groups that intersex people are often associated with are women (this is related to the large number of CEDAW references), vulnerable or minority groups, and children. Intersex issues are also raised as part of issue-based recommendations, particularly in the ‘health’ or ‘harmful practices’ thematic sections of TBs’ reports. Some treaty bodies, however, are starting to include a specific section in their reports dedicated to examining the situation of the rights of intersex people. This can be seen as a positive development, as once a section is included in the body of a report it is likely that it will be reproduced in subsequent reports. This is potentially true not only for the reviewed country but also for the reviews of other countries as well.

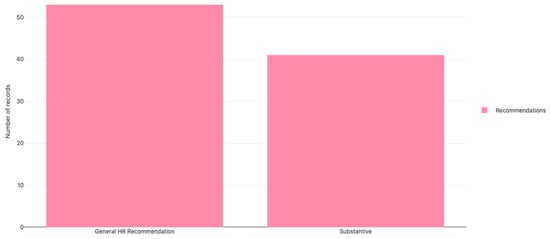

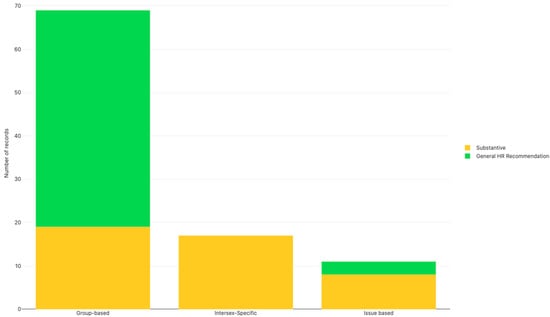

4.1.4. Substantive or General Recommendations? Are the Treaty Bodies Listening to Activists?

Another aspect that was considered in the analysis is whether TBs’ recommendations echoed intersex activist groups’ human rights demands present in activists’ public documents. For this analysis, the Malta declaration, a document emerging from the Third International Intersex Forum that took place in Valletta, Malta in 2013 (Suess Schwend 2018; Third International Intersex Forum 2013), was selected as the primary source of reference to activists’ claims, as it provides a comprehensive list of issues (problems) and demands (solutions). The Malta declaration also gathers the views of 34 activists representing 30 intersex organisations from different continents, making it more ‘universal’.

For this part of the analysis, if recommendations echoed with issues listed in the Malta declaration (or other activist documents) they were coded as substantive recommendations, as they are deemed to address issues specially related to the lived experiences of intersex persons, according to activist groups’ demands. If TBs’ recommendations were issued on broader terms, for instance, regarding issues such as the general prevention of discrimination, stigma or violence, the recommendations were coded as general human rights recommendations (even if they explicitly included intersex persons), as resonance with the specific demands of intersex activist groups was minimal. Results show a total of 41 substantive recommendations in an equal number of reports directed towards 18 European countries (see: Figure 7). Out of these numbers, 38 recommendations speak about IGS (same number of countries).

Figure 7.

Number of treaty bodies’ recommendations only for European countries segregated in substantive and general human rights recommendations.

When analysing the European data for substantive and general recommendations together with the group-based, issue-based, or intersex-specific data, I noted that while most recommendations continue to be group-based, they still contain a large number of substantive recommendations that align with intersex activist demands (see: Figure 8). Likewise, and perhaps unsurprisingly, all intersex-specific recommendations were also coded as substantive recommendations, which can be seen as a positive development, as group-specific recommendations are most likely to resonate with intersex activist groups’ demands and result in substantive recommendations calling for specific state actions. Finally, most issue-based recommendations were found to also be substantive, which can be explained by the large number of intersex substantive recommendations that can be found when TBs analyse FGM (female genital mutilation) and IGS under the lens of ‘harmful practices’. On this point, an interesting fact to highlight is that while there is a number of reports that consider intersex surgeries under the analysis of harmful practices or (female) genital mutilation, there was only one report from the CEDAW committee that framed normalising surgeries as ‘intersex genital mutilation’ (IGM). On this point, literature suggests that the ‘mutilation’ frame can be quite polarising, with most medical practitioners interviewed against it (Crocetti et al. 2020). In this sense, maybe it is a valid to question to ask if the rejection of the IGM terminology by the UN TBs, despite its use by activist and presence in activist documents and shadow reports, might be an indication of a ‘compromise’ position that recognises this harmful practice as a human rights violation but is not ready yet to grant ‘mutilation status’ such as the one given to FGM, considering the cultural politics and medical jurisdiction around it (Ammaturo 2016; Rubin 2015; Fraser 2016). Additionally, as Garland et al. (2022) have noticed, the United Nations does not have jurisdiction or the power to change medical practice, international human rights law operates at a different scale, and new protocols and standards of care for intersex people’s treatments and protections against IGS would need to be negotiated between the State and medical institutions and practitioners, a less ‘polarising’ frame might facilitate such ‘negotiations’.

Figure 8.

Number of TBs’ recommendations only for European countries segregated in group-based, issue-specific, or intersex-specific recommendations, together with substantive or general recommendations data.

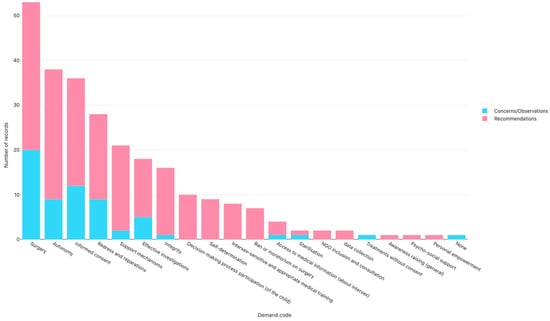

4.1.5. What Demands Are Most Visible?

I also examined the main aspects or activists’ demands the TBs have considered as priorities and decided to make visible within their reports. I found that the main issues explicitly stated in the treaty bodies’ reports referred to issues related to intersex genital surgery as well as autonomy, integrity, and informed consent claims. Other issues with high visibility were demands related to effective investigations and redress mechanisms, as well as support mechanisms for intersex people and their families. There were also other issues present in the Malta declaration in 2013 (Third International Intersex Forum 2013) that were less visible amongst the recommendations, for example, financial support for NGOs as well as their inclusion in consultation processes, claims regarding general societal awareness of intersex issues, and claims regarding sterilisation as a consequence of IGS (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Number of TBs’ recommendations only for European countries segregated by activists’ demands (Malta declaration).

5. Resonance Analysis

5.1. Finding Resonance? Intersex Activists’ Claims and UN Institutional Frames

Following the content analysis, I applied a framing resonance and legal analysis to the main claim highlighted by treaty bodies; this is IGS as a human rights violation. In the field of social movement studies, ‘resonance’ or ‘cultural resonance’ is used to describe how certain frames used by social movements to disseminate their demands can adapt to the already existing cultural values or ideas in order to achieve acceptability (Snow et al. 1986; Ferree 2003; Benford and Snow 2000). Here I use the term in a slightly different way and suggest that institutions, like cultures and societies, also possess values and ideas that are produced and reproduced through their daily functioning. Moreover, institutions like the United Nations and affiliated bodies have a strong link to legally binding frameworks; therefore, I suggest that the acceptability of certain aspects of activist claims as rights violations and subsequent visibility, expressed in the form of concluding observations and recommendations by treaty bodies, is linked to the acceptability (resonance) activists’ claims find in ideas (frameworks) that already exist and have been accepted by the UN treaty bodies.

In particular, the framing of IGS as a human rights violation is linked to aspects already recognised by TBs as human rights violations, for example, the prohibition of ill-treatment or torture, the right to the highest attainable standard of health, or the rights of the child to develop and to live a life free of violence. In this sense, intersex activists are not claiming anything new or the creation of ‘new rights’, but rather they demand the explicit recognition of a series of harmful practices and abuses that culminate in the form of intersex genital surgery as human rights violations and protections against them.

5.2. Intersex Genital Surgery as a Human Rights Violation

Intersex genital surgery is the main concern by human rights activists and has been framed as a practice that contradicts many human rights standards (Bauer et al. 2020; Ghattas 2019; Third International Intersex Forum 2013). This issue was raised in 42 treaty body reports out of the 87 pertaining to the European continent. Some elements found in the way TBs frame intersex genital surgery can serve to better analyse what these institutions perceive as problematic with this medical practice, and also if these understandings align with activists’ claims. The main aspects of surgery highlighted by TBs in the reports concerning European countries are that:

- (a)

- They are medically unnecessary

- (b)

- They are non-urgent

- (c)

- They are carried out too early or the main victims are infants or children

- (d)

- They are intended to decide or assign sex

- (e)

- They are irreversible or have long-lasting consequences

- (f)

- They entail pain or suffering

I grouped these ‘problematic’ aspects into three themes: the need or necessity of IGS, the timing or temporality of IGS, and the consequences of IGS. Below is a summary analysis of what literature and activist claims have stated on these specific aspects.

5.2.1. The Necessity of IGS

In the European countries examined, the TBs noted the issue of medical necessity in 31 out of 42 concluding observation reports that touched upon the topic of IGS. In medicine, if a procedure is not necessary for the preservation of life or bodily functions, it is said that it is elective (Gardner and Sandberg 2018). Regarding medical necessity, literature suggests that a large number of the surgeries performed on intersex children are medically unnecessary, meaning they are not strictly oriented towards preserving the life or bodily functions of the child, but rather that they are performed to ‘assign’ a sex or ‘orient’ their gender identity (Ammaturo 2016; Chase 2013; Rubin 2012; FRA 2015; CoE 2015). Likewise, activist documents have noted concerns that when law or policy makes references to surgical ‘medical necessity’ too much power is left in the hands of doctors, who are the ones that ultimately decide what medical necessity means (Ghattas 2019). Literature also questions that doctors’ opinions on the necessity of the surgeries are not free of biases, despite being often presented as such. Doctors’ opinions may be influenced by cultural biases regarding gender performativity and sex appearance within the binary and normative male/female paradigm, just as everyone else’s (Hegarty et al. 2021; Gardner and Sandberg 2018; Rubin 2012; Meoded Danon 2019). Intersex studies scholarship also shows that it is not ‘easy’ for doctors to define what is and what is not medically ‘necessary’ and different views and biases weigh in on the doctors’ decision-making process (Hegarty et al. 2021; Gardner and Sandberg 2018).

A 2019 guide created by activists and directed towards law and policy makers recommends stakeholders to avoid referring to medical necessity in intersex-related legislation:

There are few and relatively rare cases in which the intersex infant’s life is at risk and immediate treatment is actually indicated/necessary. All other interventions, despite being deferrable, are presented as equally “medically necessary” based on a misconception of what constitutes a societal problem and what is medically indicated. Evidence shows that instead of increasing an intersex individual’s health, interventions “too often lead to the opposite result”. Despite this contrary evidence, as well as a lack of positive evidence, many medical guidelines still recommend invasive surgeries and other invasive medical treatments on intersex individuals as a medical necessity, thus reinforcing the medical indication as determined by doctors (Ghattas 2019, p. 19).

Legally, the issue of medical necessity comes into play for considering ‘justifications’ for cases when there is an infringement on human rights in order to determine if such intrusion is permissible or not. The Council of Europe’s (CoE 1997) Oviedo convention, for example, considers exceptions regarding medical liability for harms and damages caused when consent cannot be obtained but the life of the patient is in danger. A framing by TBs that considers IGS as a right violation only in cases where it is medically unnecessary is already weighting in the value of a life vis a vis the value of bodily integrity. Such framing is also consistent with intersex activist groups’ demands, who do not oppose life-saving surgeries but rather question the ambiguity of what is considered medically necessary (Ghattas 2019).

5.2.2. The Temporality of IGM

The topic of temporality is visible in two distinct ways in the recommendations and concluding observations of treaty bodies. On the one hand, there are mentions that IGS is a ‘non-urgent’ procedure and therefore doctors can wait to perform it. The issue of urgency was present in 6 out of 42 records that mention IGS in the European region. Temporality is also present when references are made to the age of the persons undergoing these procedures and their inability to effectively consent. Treaty bodies referred to the early age, infancy, or childhood of the person undergoing IGS in 42 out of 42 records.

The first point on the urgency of treatments, including surgical but also hormonal and other medical treatments, is closely related to the medical necessity of interventions. Research suggests that when surgeries cannot be described as ‘medically necessary’ for the purposes of preserving the life of the child, they are often framed as ‘social emergencies’ and this way the need for ‘urgent’ treatment is justified (Ammaturo 2016; Meoded Danon 2018). Scholars such as Battaglino (2019) suggest that this feeling of urgency comes not from the fear of irreversible loss of the child’s life or bodily functions but out of fear for the social consequences that waiting to ‘define a sex’ can have in the child’s gender socialisation process. The importance that doctors and society at large give to the gender socialisation process has been noted by the United Nations treaty bodies, as in several recommendations and concluding observations examined, where the TBs recognise that IGSs are carried out for other than medical purposes, e.g., for the purpose of ‘assigning sex’.11 On the issue of temporality, Garland and Travis (2020a, p. 123) consider that “it seems, is not only being used to justify non-therapeutic medical interventions on intersex infants, but it is also used to abrogate the responsibility of the medical profession in the face of mounting external scrutiny.” They argue that the medical profession and institutional power/knowledge has successfully framed intersex bodies as temporal and in need of a fix. This notion has facilitated the claim that an intersex birth is a situation of emergency in childhood, but only a temporary one that can be ‘solved’. Likewise, the authors consider that while this narrative helps maintain intersex bodies and ‘diagnosis’ under medical authority, it also deters it from legal responsibility and criticisms from activists, families, and others over human rights abuses as ‘emergency situations’, especially those in medicine, are often a subject of less scrutiny.

Another issue highlighted by the TBs, related to temporality, is that IGS is carried out “too early”, “during infancy”, or carried out in “babies or children”.12 All of these references signal a child rights-centric view of looking at the issue (Zillén et al. 2017; Schneider 2013). This view by TBs is helpful in terms of centring specific circumstances faced by children as rights-bearers. In the particular case of intersex children, issues regarding their right to be free from violence, the right to the highest attainable standard of health, protection from harmful practices affecting their health, the right to their own development, the right to receive age-appropriate (medical) information, the right to participate in decision making processes over their medical treatment, and the right to be heard and that their views are taken into consideration in matters that affect them, all recognised by the UN (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child, are highlighted in treaty body reports.

While a child-centric view is certainly a welcome approach made by TBs, careful consideration needs to be made not to frame IGS as an issue that exclusively pertains to children and limited to the violation of the child’s agency or an event that has no repercussions into adulthood. For example, Garland and Travis (2020a) have noted the lack of importance aspects related to sexual health and pleasure are given during infancy and childhood when doing an assessment of the necessity of IGS. Berry and Monro (2022) have noted the lack of a perspective that considers the repercussions that unnecessary medical procedures and treatments have on older intersex persons and their healthcare needs. A single emphasis on children might risk making intersex adults’ struggles with the consequences of IGS invisible and leaving them out of the conversation. Indeed, in this research it was found that even when TBs’ recommendations are substantive and specific, these tend to focus on intersex children, perhaps leaving intersex activists’ claims for sustained, appropriate and informed healthcare for intersex adults who have undergone IGS and care for older intersex persons less visible (Latham and Barrett 2015; Berry and Monro 2022). A positive approach in the way TBs frame IGS should include both mentions to intersex children and adults’ rights.13

5.2.3. Consequences of IGS

The last two issues highlighted by treaty bodies have to do with the effects of IGS,14 these being that they are ’irreversible’, have ’long standing consequences’, and that these interventions often entail some degree of pain or ’suffering’. References to long-lasting consequences of IGS were present in 11 out 42 TBs’ reports that mention IGS, and references to the negative effects of IGS were found in 13 out of 42 records.15

A recognition by TBs that considers the consequences of IGS is a welcomed development, as IGS is often not a single occurrence event but rather the start of a series of episodes, surgeries and other forms of medical treatments (such as hormonal treatment) oriented towards the ‘normalisation’ of genital appearance at childhood, puberty, and adulthood (Hegarty et al. 2021; Grabham 2007; Creighton et al. 2001). Unlike most commonly-known and socially-accepted types of elective and cosmetic surgeries (e.g., plastic surgery), most types of IGS will entail significant levels of pain and discomfort that go beyond a single surgical episode for the growing child and adolescent (Hegarty et al. 2021; Grabham 2007; Creighton et al. 2001; Garland and Travis 2020b). For example, vaginal construction interventions often include dilation regimes carried out as the person grows older; these regimes can be painful, prolonged, and invasive (Hegarty et al. 2021; Creighton et al. 2001). Relevant literature also explains the results of these treatments and surgeries are not always guaranteed, as information on the level of satisfaction coming from adults who have experience these surgeries is varied and inconclusive (Köhler et al. 2012; Kreukels et al. 2019; Schweizer et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2012). Both activist documents and scholarship addressing the consequences of intersex genital surgery often recount the negative experiences of people who have undergone such procedures (Fraser 2016; Monro et al. 2019; Ghattas 2019; Grabham 2007; Ghattas et al. 2019). Often these interventions are performed on the basis that surgery is necessary in order to facilitate heterosexual sexual intercourse in adulthood, assuming the person’s sexual orientation even before puberty (Fausto-Sterling 2000; Svoboda 2013; Chase 2013; Griffiths 2018).

Legally, the importance TBs give to the consequences of IGS could be related to the way international law understands ‘permissible’ infringements of human rights as opposed to those that are not tolerated or are unjustifiable, as well as the distinction that comes from drawing the line between abuse and a violation to the prohibition of cruel, inhumane, degrading treatment or torture (Nowak 2012; De Vos 2007; ECHR 2022; Bauer et al. 2020). Understanding the prolonged and harmful effects of IGS helps sustain the claim that this medical practice should not be permitted under international law standards without the full informed consent of the person undergoing these procedures.

6. Conclusions

In this work, I have tried to demonstrate that there has been an increasing visibility of intersex issues and awareness of the human rights violations that intersex people face within international human rights monitoring bodies. Using the case of the United Nations treaty bodies I have shown that increasingly UN TBs are echoing activists’ demands and bringing visibility to these demands as human rights violations in the international fora.

To sum up my findings, results show a total of 41 intersex substantive recommendations and an equal number of reports directed towards 18 European countries; out of these, 38 recommendations speak about IGS, with the earliest record made in 2015. Notwithstanding these numbers, as stated above, only five European countries have legal regulations in place protecting intersex people from medically unnecessary genital surgeries, showing a worrying tendency to non-implementation of the UN TBs’ recommendations.

My findings also indicate that from 2009 until 2017 there was an increase in the number of observations, concerns, and recommendations regarding intersex human rights made public by treaty bodies. Some treaty bodies like the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women have notably raised the visibility of intersex issues amongst TBs, raising concerns about IGS under the ‘harmful practices’ section of their reports.

While most recommendations that mention ‘intersex’ concerned general human rights and topics such as the prevention of violence or discrimination concerns, other substantive issues raised by intersex activists such as IGS, autonomy and agency claims, demands for redress and reparations, and claims for support mechanisms are also gaining visibility. Indeed, some treaty bodies are starting to gather segregated data about the situation of intersex rights and have included an ‘intersex-specific’ section in the body of their reports. This can be seen as a positive development, as TBs would likely follow up on the progress or challenges of the reviewed country. Likewise, my findings indicate that while most recommendations that consider intersex issues are still grouped together with other groups of people, notably LGBT persons or considered as part issue-based recommendations, for example, those concerning the ‘right to health’ or ‘harmful practices’, this grouping does not mean that intersex specific concerns such as IGS are not given visibility.

While my findings show there is a limited explicit use of the ‘mutilation’ frame by UN TBs, the analysis of IGS, particularly by the CEDAW committee, under the lens of ‘harmful practices’ and often grouping IGS with female genital cutting or female genital mutilation concerns indicates to me that there is an understanding of activists’ concerns while perhaps only a partial recognition of them. As stated above, this might also be a strategy by the UN TBs not to ‘polarise’ the issue.

When looking specifically at how treaty bodies understand intersex genital surgery as a human rights violation, I discovered that issues regarding the necessity, temporality, and consequences of IGS are highlighted by TBs noticeably echoing activists’ claims of how different aspects of IGS as a practice are harmful for intersex people. To protect intersex persons from violations to their bodily integrity, activist groups such as OII Europe and ILGA Europe have recommended “the creation of a law that protects a person from any non-emergency interventions on the person’s sex characteristics until the person is mature enough to express, if they want, their wish for surgical or other medical intervention and provide informed consent. Such legislation is the only way to stop the violation of the bodily integrity of intersex people and ensure their right to self-determination” (Ghattas 2019, p. 15). This recommendation is also echoed by many treaty bodies when dealing with the topic of IGS.

Regarding the future, my research shows that while some of intersex activists’ demands seem to have found an echo with treaty bodies at the institutional level, such as IGS as a rights violation, there are still some demands that remain less visible if not invisible altogether. Issues concerning general societal awareness of intersex issues and access to comprehensive information about being intersex—perhaps better achieved via educational approaches and policies—remain to be appropriately considered by the UN TBs. Other harmful practices such as forced sterilisations, prenatal screenings, and selective abortions have so far been ignored in official human rights documents, as well as the recognition of damages caused by pathologizing approaches towards intersex people’s bodies.

Likewise, there seems to be a failure between treaty bodies’ recommendations to guarantee intersex people’s rights, particularly those pertaining to the prohibition of medically unnecessary genital surgery, and implementation at the state level. In my analysis of the European data, for instance, I discovered that 18 European countries have received recommendations concerning IGS, with the earliest record made in 2015. According to the FRA (2015), however, only four (now five) European countries have legal regulations in place protecting intersex people from unnecessary surgical ‘normalising’ treatments16. While complying with UN TBs recommendations is voluntary for treaty member states, this shows a worrying tendency to non-implementation of the UN TBs recommendations. Like Garland and Travis (2020a), I also must note that the lack of successful follow-up and implementation of the UN TBs’ recommendations does not mean this strategy should be abandoned. Activists from all causes, including intersex rights activists, use these bodies recommendations to strengthen their arguments at the domestic level, in what is known as the boomerang effect and in order to push for change. However, activists also need to be aware at the limitations of the UN system and its non-binding nature, as well as the general limitations of international human rights (soft) law (O’Flaherty 2006; Mechlem 2009). Actions that focus on multiple arenas or “interscalar” (Garland et al. 2022, p. 22) strategies (that are indeed happening) are needed in other to go from visibility to substantive change and rights recognition at the domestic level.

Overall, I believe a comprehensive understanding of how activists’ claims resonate and are echoed by human rights institutions is helpful for social movements when designing tactics and creating strategies aimed at increasing visibility, especially if resources are scarce and some issues need to be prioritised. For institutions and relevant stakeholders, having this kind of information might lead to internal reflections on the work that still needs to be done, especially regarding claims that remain unheard or unaddressed. This research piece has tried to do just that and provide a view of the trajectory of the visibility of intersex issues within the documents of the UN treaty bodies with the aim of supporting intersex people’s rights realisation through empirical evidence.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 859869. This paper reflects only the views of the author and the Agency is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful for the feedback on earlier versions of this article provided by Amets Suess Schwend, Tanya Ní Mhuirthile, Surya Monro and two anonymous reviewers. Any mistakes remain my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See for example: Stop IGM. Website. “What is IGM?”. Available at: https://stopigm.org/what-is-igm/ (accessed on 8 January 2023); OII Europe, Website. “Intersex Genital Mutilation”. Available at: https://www.oiieurope.org/igm/ (accessed on 8 January 2023). |

| 2 | See: The law of Malta (2015) “on gender identity, gender expression, and sex characteristics” [The Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act]; Portugal (2018) Lei n.º 38/2018. “Right to self-determination of gender identity and gender expression and the protection of each person’s sexual characteristics” [Direito à autodeterminação da identidade de género e expressão de género e à proteção das características sexuais de cada pessoa]; Icelandic (2019) “Gender Autonomy Act” [Kynrænt sjálfræði] Germany (2021) law “for the protection of children with variants of sex development.” [Gesetz zum Schutz von Kindern mit Varianten der Geschlechtsentwicklung]; Greece (2022) Law No. 4958/2022 “Reforms in medically assisted reproduction and other urgent regulations” [Νόμος 4958/2022: Μεταρρυθμίσεις στην ιατρικώς υποβοηθούμενη αναπαραγωγή και άλλες επείγουσες ρυθμίσεις.] Government Gazette 142/A/21-7-2022. |

| 3 | See for example: OII Europe. Web file. List of intersex specific shadow reports to UN committees from CoE Region and from countries monitoring the CoE Region. Available online: https://www.oiieurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/List-of-intersex-specific-shadow-reports-to-UN-committees-OII-Europe-June_2020.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022); OII Europe. Press Release. “30th session of the UN Human Rights Council intersex side event”. Available online: https://www.oiieurope.org/30th-session-of-the-un-human-rights-council-intersex-side-event/ (accessed on 22 November 2022); Intersex Human Rights Australia. Press release (24 July 2019) “Shadow report submission to the UN CRPD”. Available online: https://ihra.org.au/35529/shadow-report-crpd-2019/ (accessed on 22 November 2022); Intersex Human Rights Australia. Press release (11 June 2019) “Shadow report submission to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women” (2018). Available online: https://ihra.org.au/32166/shadow-report-submission-cedaw/ (accessed on 22 November 2022); Stop IGM. Website. “About the NGO”. Available at: https://stopigm.org/about-us/about-the-ngo/ (last accessed: 22 November 2022); see also: Intersex.shadowreport.org Website: https://intersex.shadowreport.org/ (accessed on 22 November 2022). |

| 4 | For more information see: OII Europe. Web file. List of intersex specific shadow reports to UN committees from CoE Region and from countries monitoring the CoE Region. Available online: https://www.oiieurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/List-of-intersex-specific-shadow-reports-to-UN-committees-OII-Europe-June_2020.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2022). |

| 5 | These are: the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD, 21 December 1965), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, 16 December 1966), the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR, 16 December 1966), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, 18 December 1979), the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT, 10 December 1984), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC, 20 November 1989) the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICMW, 18 December 1990), the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (CPED, 20 December 2006), the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, 13 December 2006). |

| 6 | There are also optional protocols that are adjacent to the nine core treaty bodies already mentioned. But for the purposes of this research, I only consider the main treaty bodies. |

| 7 | United Nations. Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: Concluding observations on sixth periodic report of Denmark. 12 November 2019 E/C.12/DNK/CO/6 Parr.65. |

| 8 | The table looks at trans and transgender women combined results. |

| 9 | The actual term used is “differences (disorders) or sex developments”, the TB recommends Denmark to stop using ‘disorders’ as it considers it a pathologizing term, but it still showed up in the query. |

| 10 | These data consider Western Europe and Eastern Europe data together, while the UN official UHRI data seem to divide it. |

| 11 | See foe example: Committee against Torture Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Austria. 27 January 2016. CAT/C/AUT/CO/6, Human Rights Committee. Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Belgium. 6 December 2019. CCPR/C/BEL/CO/6, Human Rights Committee. Concluding observations on the seventh periodic report of Finland. 3 May 2021. CCPR/C/FIN/CO/7, Committee against Torture. Concluding observations on the seventh periodic report of France. 10 June 2016. CAT/C/FRA/CO/7, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Germany. 27 November 2018. E/C.12/DEU/CO/6, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Concluding observations on the combined sixth and seventh periodic reports of Ireland. 9 March 2017. CEDAW/C/IRL/CO/6-7. |

| 12 | See for instance: Human Rights Committee. Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Belgium. 6 December 2019. CCPR/C/BEL/CO/6 Parr.22; Committee on the Rights of the Child, Concluding observations on the combined third to sixth periodic reports of Malta. 26 June 2019. CRC/C/MLT/CO/3-6 Parr.29; Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Concluding observations on the combined fourth and fifth periodic reports of Switzerland. 25 November 2016 CEDAW/C/CHE/CO/4-5 Parr.24. |

| 13 | See also: Carpenter, Morgan. Web post. (2015) “intersex and ageing”. Available online: https://morgancarpenter.com/intersex-and-ageing/ (accessed on 22 November 2022). |

| 14 | Committee against Torture Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Austria. 27 January 2016. CAT/C/AUT/CO/6, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of Belgium. 26 March 2020. E/C.12/BEL/CO/5, Committee against Torture. Concluding observations on the combined sixth and seventh periodic reports of Denmark. 4 February 2016. CAT/C/DNK/CO/6-7, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Concluding observations on the combined seventh and eighth periodic reports of Germany. 9 March 2017 CEDAW/C/DEU/CO/7-8, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of Germany. 27 November 2018. E/C.12/DEU/CO/6, Committee on the Rights of the Child. Concluding observations on the combined third and fourth periodic reports of Ireland. 1 March 2016. CRC/C/IRL/CO/3-4, Committee on the Rights of the Child, Concluding observations on the combined third to sixth periodic reports of Malta. 26 June 2019. CRC/C/MLT/CO/3-6, Committee on the Rights of the Child. Concluding observations on the combined second to fourth periodic reports of Switzerland. 26 February 2015. CRC/C/CHE/CO/2-4, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women Concluding observations on the combined fourth and fifth periodic reports of Switzerland. 25 November 2016. CEDAW/C/CHE/CO/4-5, Committee on the Rights of the Child Concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. 12 July 2016, CRC/C/GBR/CO/5, Committee against Torture Concluding observations on the sixth periodic report of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. 7 June 2019. CAT/C/GBR/CO/6. |

| 15 | See for example: Committee against Torture. Concluding observations on the combined sixth and seventh periodic reports of Denmark. 4 February 2016. CAT/C/DNK/CO/6-7, Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Concluding observations on the fifth periodic report of Belgium. 26 March 2020. E/C.12/BEL/CO/5, Committee against Torture. Concluding observations on the seventh periodic report of France. 10 June 2016. CAT/C/FRA/CO/7, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Concluding observations on the combined seventh and eighth periodic reports of Germany. 9 March 2017. CEDAW/C/DEU/CO/7-8, Committee on the Rights of the Child. Concluding observations on the combined third and fourth periodic reports of Ireland. 1 March 2016. CRC/C/IRL/CO/3-4, Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Concluding observations on the combined sixth and seventh periodic reports of Luxembourg. |

| 16 | Now 5 countries considering the most recent developments in Greece. |

References

- Allendoerfer, Michelle Giacobbe, Amanda Murdie, and Ryan M. Welch. 2020. The Path of the Boomerang: Human Rights Campaigns, Third-Party Pressure, and Human Rights. International Studies Quarterly 64: 111–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammaturo, Francesca Romana. 2016. Intersexuality and the “Right to Bodily Integrity”. Social & Legal Studies 25: 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglino, Vanesa Lorena. 2019. Intersexualidad: Un Análisis Crítico de Las Representaciones Socioculturales Hegemónicas de Los Cuerpos y Las Identidades. In Monográfico Sobre Género y Diversidad Sexual. Edited by Almudena García Manso. Special Issue, Methaodos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 7: 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Markus, Daniela Truffer, and Daniela Crocetti. 2020. Intersex Human Rights. International Journal of Human Rights 24: 724–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benford, Robert D., and David A. Snow. 2000. Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, Adeline W., and Surya Monro. 2022. Ageing in Obscurity: A Critical Literature Review Regarding Older Intersex People. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 30: 2136027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, Morgan. 2016. The Human Rights of Intersex People: Addressing Harmful Practices and Rhetoric of Change. Reproductive Health Matters 24: 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, Cheryl. 2013. Hermaphrodites with Attitude: Mapping the Emergence of Intersex Political Activism. In The Transgender Studies Reader. Edited by Susan Stryker and Stephen Whittle. New York: Routledge, pp. 300–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoE (Council of Europe). 1997. Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. (Oviedo Convention). Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/bioethics/oviedo-convention (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- CoE (Council of Europe Commisioner for Human Rights). 2015. Human Rights and Intersex People. Issue Paper. Strasbourg. Available online: https://book.coe.int/en/commissioner-for-human-rights/6683-pdf-human-rights-and-intersex-people.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Collister, Heather, Thomas Helm, Pooja Patel, and Olivia Starrenburg, eds. 2015. A Simple Guide to the UN Treaty Bodies. Geneva: International Service for Human Rights. Available online: https://ishr.ch/latest-updates/updated-simple-guide-un-treaty-bodies-guide-simple-sur-les-organes-de-traites-des-nations-unies/ (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Creighton, Sarah M., Catherine L. Minto, and Stuart J. Steele. 2001. Objective Cosmetic and Anatomical Outcomes at Adolescence of Feminising Surgery for Ambiguous Genitalia Done in Childhood. The Lancet 358: 124–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, Daniela, Elisa A. G. Arfini, Surya Monro, and Tray Yeadon-Lee. 2020. “You’re Basically Calling Doctors Torturers”: Stakeholder Framing Issues around Naming Intersex Rights Claims as Human Rights Abuses. Sociology of Health & Illness 42: 943–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, Francine. 2015. LGBT and (Dis)United Nations: Sexual and Gender Minorities, International Law, and UN Politics. In Sexualities in World Politics. Edited by Manuela Lavinas Picq and Markus Thiel. London: Routledge, pp. 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Georgiann. 2014. The Power in a Name: Diagnostic Terminology and Diverse Experiences. Psychology and Sexuality 5: 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, Christian M. 2007. Mind the Gap: Purpose, Pain, and the Difference between Torture and Inhuman Treatment. Human Rights Brief 14: 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dondoli, Giulia. 2015. LGBTI Activism Influencing Foreign Legislation. Melb. Journal of International Law 16: 124. [Google Scholar]

- Dreger, Alice D., and April M. Herndon. 2009. Progress and Politics in the Intersex Rights Movement Feminist Theory in Action. GLQ 15: 199–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECHR (European Court of Human Rights). 2022. M v. France. Application no. 42821/18. Decision of the Fifth Section of 26 of April 2022. Strasbourg. Available online: https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-217430%22]} (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- European Parliament. 2019. Resolution of 14 February 2019 on the Rights of Intersex People. 2018/2878(RSP). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019IP0128 (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Fausto-Sterling, Anne. 2000. Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality, 1st ed. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0465077137. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, Myra Marx. 2003. Resonance and Radicalism: Feminist Framing in the Abortion Debates of the United States and Germany. American Journal of Sociology 109: 304–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FRA (EU Agency for Fundamental Rights). 2015. The Fundamental Rights Situation of Intersex People. Vienna: FRA. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2015/fundamental-rights-situation-intersex-people (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Fraser, Sylvan. 2016. Constructing the Female Body: Using Female Genital Mutilation Law to Address Genital-Normalizing Surgery on Intersex Children in the United States. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare 9: 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaer, Felice D. 2003. Implementing International Human Rights Norms: UN Human Rights Treaty Bodies and NGOs. Journal of Human Rights 2: 339–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Melissa, and David E. Sandberg. 2018. Navigating Surgical Decision Making in Disorders of Sex Development (DSD). Frontiers in Pediatrics 6: 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, Fae, Kay Lalor, and Mitchell Travis. 2022. Intersex Activism, Medical Power/Knowledge and the Scalar Limitations of the United Nations. Human Rights Law Review 22: ngac020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, Fae, and Mitchell Travis. 2020a. Temporal Bodies: Emergencies, Emergence, and Intersex Embodiment. In A Jurisprudence of the Body. Edited by C. Dietz, M. Travis and M. Thomson. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 119–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, Fae, and Mitchell Travis. 2020b. Making the State Responsible: Intersex Embodiment, Medical Jurisdiction, and State Responsibility. Journal of Law and Society 47: 298–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, Dan Christian. 2019. Protecting Intersex People in Europe: A Toolkit for Law and Policymakers. Brussels: ILGA Europe. Berlin: OII Europe. Available online: https://www.oiieurope.org/protecting-intersex-people-in-europe-a-toolkit-for-law-and-policy-makers/ (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Ghattas, Dan Christian, Ins A Kromminga, Irene Kuzemko, Kitty Anderson, and Audrey Aegerter, eds. 2019. #MyIntersexStory. Personal Accounts by Intersex People Living in Europe, 1st ed. Berlin: OII Europe. Available online: https://www.oiieurope.org/myintersexstory-personal-accounts-by-intersex-people-living-in-europe/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Grabham, Emily. 2007. Citizen Bodies, Intersex Citizenship. Sexualities 10: 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, David Andrew. 2018. Diagnosing Sex: Intersex Surgery and “sex change” in Britain 1930–1955. Sexualities 21: 476–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegarty, Peter, Marta Prandelli, Tove Lundberg, Lih-Mei Liao, Sarah Creighton, and Katrina Roen. 2021. Drawing the Line Between Essential and Nonessential Interventions on Intersex Characteristics with European Health Care Professionals. Review of General Psychology 25: 101–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Ieuan A., Chris Houk, S. Faisal Ahmed, Peter A. Lee, and Wilkins Lawson. 2006. Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2: 148–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IACHR (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights). 2015. Violence against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Persons in the Americas. Official Records. Washington, DC: OAS. Available online: https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/reports/pdfs/ViolenceLGBTIPersons.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Joachim, Jutta. 2003. Framing Issues and Seizing Opportunities: The UN, NGOs, and Women’s Rights. International Studies Quarterly 47: 247–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, Rachael Lorna. 2006. Feminist Influences on the United Nations Human Rights Treaty Bodies. Human Rights Quarterly 28: 148–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Tiffany. 2018. Intersex Studies: A Systematic Review of International Health Literature. SAGE Open 8: 215824401774557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keck, Margaret E., and Kathryn Sikkink. 2018. Transnational Advocacy Networks in International and Regional Politics. International Social Science Journal 68: 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, Birgit, Eva Kleinemeier, Anke Lux, Olaf Hiort, Annette Grüters, Ute Thyen, and DSD Network Working Group. 2012. Satisfaction with Genital Surgery and Sexual Life of Adults with XY Disorders of Sex Development: Results from the German Clinical Evaluation Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 97: 577–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreukels, Baudewijntje P. C., Peggy T. Cohen-Kettenis, Robert Roehle, Tim C. van de Grift, Jolanta Slowikowska-Hilczer, Hedi Claahsen-van der Grinten, Angelica Lindén Hirschberg, Annelou L C de Vries, Nicole Reisch, Claire Bouvattier, and et al. 2019. Sexuality in Adults with Differences/Disorders of Sex Development (DSD): Findings from the Dsd-LIFE Study. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 45: 688–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, J. R., and Catherine Barrett. 2015. Appropriate Bodies and Other Damn Lies: Intersex Ageing and Aged Care. Australasian Journal on Ageing 34: 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Peter A., Anna Nordenström, Christopher P. Houk, S. Faisal Ahmed, Richard Auchus, Arlene Baratz, Katharine Baratz Dalke, Liao Lih-Mei, Karen Lin-Su, Leendert H J Looijenga, 3rd, and et al. 2016. Global Disorders of Sex Development Update since 2006: Perceptions, Approach and Care. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 85: 158–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Peter A., Justine Schober, Anna Nordenström, Piet Hoebeke, Christopher Houk, Leendert Looijenga, Gianantonio Manzoni, William Reiner, and Christopher Woodhouse. 2012. Review of Recent Outcome Data of Disorders of Sex Development (DSD): Emphasis on Surgical and Sexual Outcomes. Journal of Pediatric Urology 8: 611–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundberg, Tove, Peter Hegarty, and Katrina Roen. 2018. Making Sense of “Intersex” and “DSD”: How Laypeople Understand and Use Terminology. Psychology and Sexuality 9: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechlem, Kerstin. 2009. Treaty Bodies and the Interpretation of Human Rights. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law 42: 905. [Google Scholar]

- Meoded Danon, Limor. 2018. Time Matters for Intersex Bodies: Between Socio-Medical Time and Somatic Time. Social Science and Medicine 208: 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danon, Limor Meoded. 2019. Comparing Contemporary Medical Treatment Practices Aimed at Intersex/DSD Bodies in Israel and Germany. Sociology of Health & Illness 41: 143–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monro, Surya, Daniela Crocetti, and Tray Yeadon-Lee. 2019. Intersex/Variations of Sex Characteristics and DSD Citizenship in the UK, Italy and Switzerland. Citizenship Studies 23: 780–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulé, Nick J. 2018. LGBTQI-Identified Human Rights Defenders: Courage in the Face of Adversity at the United Nations. Gender and Development 26: 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, Manfred. 2012. What’s in a Name? The Prohibitions on Torture and Ill Treatment Today. In The Cambridge Companion to Human Rights Law. Edited by Conor Gearty and Costas Douzinas. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 307–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, Michael. 2006. The Concluding Observations of United Nations Human Rights Treaty Bodies. Human Rights Law Review 6: 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). 2017. Resolution 2191 (2017). Promoting the Human Rights of and eliminating Discrimination against Intersex People. 2017. Available online: https://assembly.coe.int/nw/xml/XRef/Xref-XML2HTML-en.asp?fileid=24232 (accessed on 27 December 2022).

- Ravesloot, Saskia. 2021. The Universal Periodic Review beyond the Binary Advancing the Rights of Persons with Variations in Sex Characteristics. Paper presented at 8th International Conference on Gender & Women Studies, Singapore, July 29; Available online: https://asianstudies.info/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/ProceedingsGWS2021.pdf#page=7 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Reis, Elizabeth. 2007. Divergence or Disorder?: The Politics of Naming Intersex. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 50: 535–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, David A. 2012. “An Unnamed Blank That Craved a Name”: A Genealogy of Intersex as Gender. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 37: 883–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, David A. 2015. Provincializing Intersex: US Intersex Activism, Human Rights, and Transnational Body. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 36: 51–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, Erik. 2013. An Insight into Respect for the Rights of Trans and Intersex Children in Europe. Strasbourg: Intersex & Transgender Luxembourg a.s.b.l. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/168047f2a7 (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Schweizer, Katinka, Franziska Brunner, Christina Handford, and Hertha Richter-Appelt. 2014. Gender Experience and Satisfaction with Gender Allocation in Adults with Diverse Intersex Conditions (Divergences of Sex Development, DSD). Psychology and Sexuality 5: 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, David A., E. Burke Rochford, Steven K. Worden, and Robert D. Benford. 1986. Frame Alignment Processes, Micromobilization, and Movement Participation. American Sociological Review 51: 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]