1. Introduction

Since 2007, over 650 public schools have closed in Puerto Rico, representing nearly 44% of all public schools on the archipelago (

Yedidia et al. 2020). In the aftermath of closures, hundreds of now-vacant school buildings signify a void where vibrant education centers once stood and present a politicized regional development dilemma for how these abandoned properties will be repurposed, if at all. Mass school closures have become increasingly commonplace. From 2004 to 2017, over 23,000 schools were closed throughout the US, displacing an average of over 250,000 students annually (

Delpier 2021).

Shuttered schools can have widespread and lingering consequences, often falling disproportionately on marginalized communities (

Delpier 2021). Schools not only serve as institutions for education and learning but also offer community resources to meet social, recreational, health, and personal needs (

Lytton 2011). Thus, schools function as community anchors and hubs for educating and employing residents, especially in rural areas, and provide a distinct community identity and sense of place (

Kearns et al. 2009;

Rosenbaum et al. 2019;

Witten et al. 2001).

Recent studies have investigated school closures and their consequences, focusing on decision-making criteria for closures, their economic ramifications, and racial inequity and opposition (

Brazil and Candipan 2022;

Tieken and Auldridge-Reveles 2019). Less attention has been given to how abandoned schools are managed and priorities for their post-closure use. Because school buildings hold emotional and material value, and their reuse can significantly buffer the loss of a community resource, decisions on how to repurpose them present complex challenges and are often politicized. Few school districts have formalized procedures to collect and consider resident input to decide on school repurposing plans or have the capacity to navigate market challenges along with state and local policies (

Dowdall and Warner 2013). In rare circumstances where school districts involve residents in the decision-making process, they tend to be consulted on proposed plans, which misses opportunities to explore and support community visions to repurpose schools in ways that minimize the damage of closures.

In the wake of Puerto Rico’s mass school closures, a novel approach for repurposing school buildings has emerged. Throughout Puerto Rico, organized community groups have reclaimed abandoned schools—sometimes with government permission, sometimes without—with the hope of transforming them into vibrant community centers and reviving a lost local asset (

Donnelly-Deroven 2019). Known locally as “escuelas rescatadas” (rescued schools), these projects comprise a variety of programs and services that address community development priorities while maintaining their role as a community anchor. Puerto Rico’s rescued schools are directly utilized by residents to serve as anchoring social institutions once again, which aligns with

Hamilton’s (

2013) ideal adaptive reuse project; that is, one which revitalizes the building’s tie to the community through a new appropriate capacity while maintaining its historic fabric, thus, replacing the anchoring void caused by the school’s loss.

This study explores school repurposing efforts throughout Puerto Rico, focusing on rescued school initiatives and their development. Through a multi-method approach, we categorized and mapped 161 repurposed schools throughout Puerto Rico—38 of which are rescued schools. We conducted interviews with 12 rescued schools coupled with 2 focus groups comprising 13 rescued school representatives to understand their motivations, programs, and challenges. Our results indicate that closed schools offer a galvanizing opportunity for motivated community members to restore and expand upon a lost local asset and meet emerging community challenges; however, gaining long-term ownership of school buildings and securing financial resources and volunteer commitment impede the potential value of these projects. We argue that government authorities can minimize the negative effects of school closures by forging new partnerships between community-based organizations, local governments, and other supportive actors to productively repurpose closed schools to maintain their role as an anchor institution and offer a model in “grassroots adaptive reuse” applicable to other cities.

1.1. School Closures and Their Consequences

School closures have been a disruptive phenomenon for hundreds of communities across the United States. School districts are experiencing aging school facilities, increasing budget constraints, and pressure to improve education spending efficiency, coupled with enrollment decline due to demographic shifts and competition with charter schools (

Barber 2018). Mass closures have been linked to political–economic shifts and institutional reforms grounded in neoliberal agendas (

Basu 2007). Public schools are prime targets for urban and regional renewal strategies that foster the rationalization of public assets and the divestment of public-sector support in favor of entrepreneurial and private market investment (

Lynch 2022). School closures have also been described as a means to attract higher-income residents and private investment into disadvantaged neighborhoods by closing underperforming schools and increasing school choice options (

Bierbaum 2021b;

Davis and Oakley 2013). Unsurprisingly, school closures engender controversy.

City officials have justified school closures as a benevolent policy that will improve cost efficiency and educational quality while aspiring to address the inequality of disadvantaged students and residents (

Davis and Oakley 2013;

Tieken and Auldridge-Reveles 2019). School closure decisions are typically grounded in two criteria: academic performance and school enrollment (

Tieken and Auldridge-Reveles 2019). These criteria are used to frame school closures as opportunities to provide better educational opportunities to marginalized communities, whether that involves transferring students to larger schools with more facilities and better educational experiences or consolidating schools to integrate and equalize Black and White student experiences. In contrast, parents, students, and community members tend to view school closures as discriminatory and harmful, especially Black and Latino populations who absorb the majority of closures (

Nuamah 2020), leading to staged protests, hunger strikes, lawsuits, and other forms of resistance to save their schools (

Brazil 2020;

Tieken and Auldridge-Reveles 2019). The prevailing decision-making criteria have led to school closures occurring disproportionately in socio-economically disadvantaged and minority neighborhoods, creating new modes of community disposability (

McWilliams and Kitzmiller 2019). Lower-resourced neighborhoods are more likely to have lower-resourced and lower-performing schools than more affluent areas (

Owens and Candipan 2019). In addition, declining student enrollment is often driven by the “White flight” out of public schools resulting from school district desegregation, the increase in private schools, and the general out-migration into suburban neighborhoods (

Zhang and Ruther 2020).

Schools are a unique and often undervalued publicly funded societal infrastructure. Beyond a place for education, many communities rely on schools to house health clinics, daycare centers, after-school social programs, and recreation spaces, among other activities. Public schools serve as a “third place”—that is, a place other than work or home where people meet to build relationships and supportive networks (

Rosenbaum et al. 2019). The loss of a school can deteriorate a sense of community identity (

Witten et al. 2001). Schools are referred to as storehouses of history and cultural pillars for their role in educating and employing residents and bringing people together. They hold a special intrinsic value since generations of residents spent their formative years in these institutions, creating notions of communal ownership (

Cranston 2017;

Ewing 2018;

Kearns et al. 2009). School closures cause neighborhoods to become less attractive to families and, in more rural areas, can even threaten the economic viability of the entire community (

Cranston 2017;

People for Education 2009). Left abandoned, schools present a potential hazard. Vacant buildings decrease property values, invite vandalism, discourage investments, impose financial costs on municipalities, and generally lower residents’ quality of life (

Cohen 2001). While investments in school facilities, under the right conditions, can catalyze community development in myriad ways, discussions to improve schools and communities have remained largely in the hands of scholars, practitioners, and policymakers (

Bierbaum et al. 2023;

Good 2022).

1.2. Adaptive Reuse of Abandoned School Buildings

An emerging literature has explored how various entities are adaptively reusing school buildings to breathe new life into communities. Adaptive reuse refers to the process of reusing an existing building for a different purpose than it was originally designed for and can help conserve social, cultural, and historical values held by community residents, providing a psychological and sociological sense of stability (

Bullen and Love 2011). For some, repurposing schools is a form of “restorative nostalgia” that reconstructs the past in new ways (

Boym 2008). Because community members often want school buildings repurposed for public use, proposed commercial use can be divisive (

Dowdall and Warner 2013). The adaptive reuse literature describes an ideal project as one that protects the values and character that the community attaches to the building, maintains its social and historic fabric, and replaces the anchoring element lost with the school’s closure (

Hamilton 2013;

Mısırlısoy and Günçe 2016).

As mass school closures have increased across the US (

Dowdall and Warner 2013), school districts must grapple with what to do with their vacant buildings. School properties have become key sites of contestation in the politics of place and community change (

Bierbaum 2021a). School closures, sales, and reuse can effectively erase communities’ multigenerational schooling experiences (

Khalifa et al. 2014) and reinforce social suffering in public schools and neighborhoods (

Dumas 2014). These experiences extend beyond the walls of the school building to the broader neighborhood and demonstrate how maintaining linkages to the past is critical to making sense of the future (

Bierbaum 2021b).

Repurposing schools tends to attract less attention and passion than closing them in the first place, but the process takes considerable effort from government authorities, and the outcomes can significantly impact the surrounding community. Finding new owners to repurpose closed schools entails navigating market challenges, adhering to state and local policies, and balancing sometimes conflicting priorities on how to best use the property. Government authorities expecting significant sums for school properties are often disappointed, as sale prices are typically between USD 200,000 and USD 1 million, well below initial projections (

Dowdall 2015). The low sale prices are attributed to poor building conditions, inflexible layouts for repurposing, and locations in residential areas with decreasing populations. Even when schools have been resold, there is no guarantee they will successfully be reused since many aspects of the re-development process, such as repairs, zoning approvals, financing, and community concerns, can all delay or derail a project (

Dowdall 2015). Few districts have formalized procedures to collect and consider resident input to decide how to repurpose schools (

Anderson 2015); only 1 out of the 12 school districts studied by The Pew Charitable Trusts had a formal guideline for repurposing closed schools (

Dowdall and Warner 2013). Over time, abandoned school buildings deteriorate, making them even harder to resell and increasing the likelihood that they become blighted properties.

Because shuttered schools invoke a stronger sense of community ownership and passionate opinions than other vacant buildings, repurposing schools in ways that do not align with residents’ vision for their community can confront significant opposition. Several studies have highlighted positive examples of how school districts have included community input within the reuse decision-making processes. For example, in Atlanta, the school district convened a “repurposing committee” comprised of school and city officials along with community representatives who vote on potential lessees’ or buyers’ plans to purchase and repurpose the school property. In Kansas City, the district promotes public engagement with prospective developers by organizing site tours, public meetings, and other efforts to ensure community interactions. Philadelphia’s reuse policy requires bids to be reviewed by an evaluation team composed of members of the school district, city planning commission, and affected civic groups (

Dowdall and Warner 2013). While these forms of community consultation productively incorporate community feedback, they can also be interpreted as a strategy to limit disruptions to developer’s school repurposing plans and may overlook opportunities to support community visions for how adaptive reuse of closed schools can best meet local needs.

1.3. Puerto Rico’s School Closures: Causes and Counteractions

Puerto Rico’s school closures have progressed incrementally and have been spurred by a combination of emigration, natural disasters, and austerity cuts in response to Puerto Rico’s debt crisis. Mass closures began in 2007 due to increased emigration from Puerto Rico (

Hinojosa et al. 2019). Puerto Rico’s under-18 population has dramatically decreased from approximately 1,018,000 in 2006 to 869,000 in 2011 to 696,000 in 2016 to 597,000 in 2021 (

U.S. Census Bureau n.d.). From 2007 to 2011, approximately 20 schools were closed annually because of decreased student population (

Yedidia et al. 2020). In 2014, the Puerto Rican government declared bankruptcy, contributing to a larger series of closures. Roughly 80 schools closed before the 2015 school year, and within the next three years, another 100 closures occurred. This was followed by 263 school closures before the 2018 school year due to mass population emigration and the irreparable destruction of many schools resulting from Hurricanes Irma and Maria. Collectively, these school closures amounted to 44% of Puerto Rico’s public schools, the majority in rural areas, rerouting thousands of students to neighboring public schools (

Hinojosa 2018;

Yedidia et al. 2020).

Austerity measures resulting from Puerto Rico’s debt crisis have been a contested rationale for school closures and opened a neoliberal educational reform (

Brusi 2022;

Virella 2023). In 2014, the Puerto Rican government announced an inability to repay its debt, which had accumulated to USD 72 billion—nearly 70% of the island’s Gross Domestic Product. As a result, President Obama signed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA), which aimed to help Puerto Rico restructure and reduce their debt by 80% while also largely safeguarding investors (

Stojanovic and Wessel 2022). PROMESA permitted Puerto Rico to declare bankruptcy and ushered in a series of austerity measures, one of which involved aspirations to save USD 150 million by closing schools (

Strauss 2018). At the same time, in March 2018, Puerto Rico Governor Ricardo Rosselló adopted the Educational Reform Act, which allowed for the creation of charter schools and created a voucher system for students to attend intra-district public schools or private schools, which were offered to 3% of students in the 2019–2020 school year. This reform policy was argued to affect lower-income families disproportionately since they could not afford private education (

Moore and Yedidia 2019). While school closures were part of an overarching plan to pull Puerto Rico out of debt, recent studies have shown that it resulted in minimal savings (

Centro de Periodismo Investigativo 2022;

Renta et al. 2021).

Like other US cities, school closures in Puerto Rico led to negative consequences. Families had longer commutes to new schools (

Rodriguez 2015), student enrollments declined (

Yedidia et al. 2020), and academic performance suffered (

Rivera Rivera 2022). Teachers faced difficulties as well, many having to switch subjects and grade levels while enduring salary freezes since 2008 (

Lake 2019;

Robles 2017). Schools that remained open often faced overcrowding, and some requested Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) trailers to accommodate the influx of students (

Martinez and Lee 2018). Thus, school closures not only fractured the quality of remaining public schools and long-standing community resources but also ushered in a neoliberal education system (

Brusi 2020).

In response, various organizations have applied to obtain and repurpose vacant school buildings. On 9 May 2017, Ricardo Rosselló, the Governor of Puerto Rico at the time, signed an executive order that outlined plans to address ownership of abandoned property by appointing a committee chaired by the Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority (AAFAF, in Spanish). The law established a sub-committee called the Evaluation and Disposal of Real Estate Assets Committee (CEBDI, in Spanish) to establish a priority system for the transfer of school properties, receive and evaluate proposals, and maintain an efficient and effective procedure. Rosselló stated their vision for the closed schools must “engage in activities for the common good, whether for the use of non-profit or commercial organizations, or that promote the activation of the real estate market and the economy in general” (Exec. Order No. 2017-032). Although the government committee claimed to be transparent about the application and approval process, community groups have shared personal experiences that tell a different story (

Ramos 2020). Moreover, the formal bureaucratic evaluation process prohibits grassroots community groups without sufficient status designations and financial resources to submit applications.

Despite the CEBDI plans for vacant schools, many grassroots organizations have been “rescuing” abandoned schools and repurposing them as a community resource. These opportunistic community groups have been empowered to restore a piece of their culture and history while maintaining the school building as a critical social infrastructure. Through persistent negotiations with government officials, community groups have occupied, gained permission to lease, or on rare occasions, gained ownership of vacant schools to provide a variety of programs and services that address localized community development priorities, maintain their role as a “third place”, and repair residents’ relationships to community identity and heritage. In contrast to typical school repurposing projects where developers are well-resourced with pre-established plans for their acquired school building, Puerto Rico’s rescued schools comprise grassroots projects with deep community engagement to shape and implement repurposing efforts, have minimal resources, and advance projects incrementally, often repurposing one room at a time. The rescued school phenomenon in Puerto Rico offers an alternative, grassroots, adaptive reuse approach for repurposing closed schools and pushes back against neoliberal agendas that seek to maximize profit while avoiding community disruptions through facile consultation processes.

2. Materials and Methods

This study derived from a multi-year shared action learning collaboration between Worcester Polytechnic Institute’s Puerto Rico Project Center and Taller Comunidad la Goyco to explore the rescued school phenomenon throughout Puerto Rico and ways to build a constructive support system between fledging rescued schools. This paper draws from research methods conducted between January 2022 and March 2023 to explore the scope of repurposed schools throughout Puerto Rico, along with the ambitions and challenges faced by rescued school initiatives.

Mapping repurposed schools in Puerto Rico presented several challenges since there is no publicly accessible database of repurposed schools, and many are new organizations that operate without a formal organizational structure or online presence. To address these challenges, we implemented a multi-method approach to identify repurposed schools, which included (1) obtaining a list of closed and sold school buildings from government agencies, (2) phone interviews with municipalities, (3) internet research via online search engines, and (4) a snowball sampling method.

Upon request, Puerto Rico’s Department of Education provided us with a list of closed schools whose ownership was transferred to a new entity. This list enabled us to identify several closed schools that were purchased by other entities, but the majority were owned by the Department of Transportation and Public Works. In addition, the Real Estate Evaluation and Disposition Committee shared a list of 303 closed schools as of 2022, with 131 being either purchased or rented by a new entity.

These government lists provided information on formal ownership transfers; however, some school repurposing projects operate informally, which led to the following supplemental methods. We contacted all 78 municipal government offices in Puerto Rico to inquire about repurposed school projects within their jurisdiction and spoke with representatives from 39 of the municipalities. We also conducted internet searches to identify additional schools and gather descriptive information on repurposed schools using keywords in English and Spanish such as “community centers” (el centro comunitario), “rescued schools” (escuelas rescatadas), and “closed schools” (escuelas cerradas). We also used the names of repurposed schools identified in the previous two methods to obtain additional information on these organizations. Finally, we employed a snowball sampling method to generate additional leads by asking each repurposed school project we interviewed if they knew of other projects. These methods resulted in the following information for each repurposed school: name of a closed school, name and brief description of the repurposed school project (e.g., whom they serve, programs provided, etc.), contact information, and the address and GPS location. We then visualized the data using ArcGIS.

Interviews and focus groups with rescued school leaders explored their organizational motivations and experiences. We contacted all identified rescued school projects (n: 38) to request interviews and conducted twelve interviews via phone, online conferencing platform, or in-person (see

Table 1). The interviews were semi-structured and organized thematically into three sections: (1) Initiative origins and background information; (2) Organizational goals and challenges; (3) Desired support. The interviews lasted 45–60 min. Transcriptions of the interviews were analyzed using an inductive coding approach.

In addition, we facilitated two focus groups with rescued schools to provide opportunities for solidarity and mutual learning and to explore interest in a rescued school support network. We invited rescued school representatives to collaboratively discuss their origins and motivations, programs, challenges, and desired support. Both focus groups lasted 90 min and were hosted at Taller Comunidad La Goyco in San Juan. The first focus group took place on 6 February 2023, and comprised nine members representing three rescued schools. The second focus group occurred on 27 February 2023 and comprised seven members from three rescued schools. Similar to the interviews, transcriptions of the focus groups were analyzed using an inductive coding approach.

There are several limitations regarding our methods worth noting. We were unable to speak with a representative from every municipality, which means we likely missed repurposed schools within those municipalities. Additionally, it is unrealistic for municipal employees to be immediately aware of the status of closed school buildings for each school within their jurisdiction. Our focus groups were conducted in person in San Juan to build relationships between similar organizations. Rescued schools located away from San Juan were unable to attend and share their experiences, which may offer significant differences since they are located further away from the capital city.

3. Results

The results of our study are divided into two sections. First, we provide an overview of how abandoned schools are being repurposed in Puerto Rico. Second, we offer descriptive information on the programs and services provided by rescued schools, along with the challenges faced by this form of grassroots adaptive reuse.

3.1. Puerto Rico’s Repurposed Schools

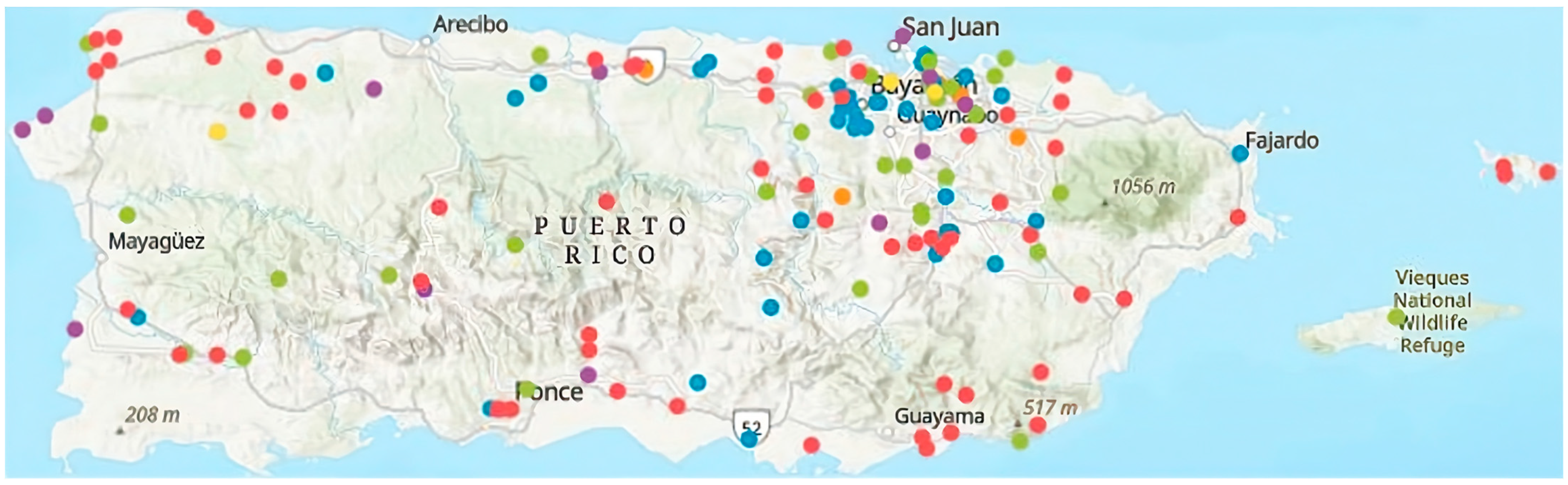

We identified 161 closed schools whose ownership has been transferred to a new entity (see

Figure 1). The most common ownership entities were municipalities, private education institutes, and rescued schools. A total of 64 schools were transferred to municipal governments, representing the most common ownership entity. While it is unknown what most municipalities have planned for their schools, some initial ideas have been shared in the media. For example,

Ramos (

2020) reported that seven municipalities received funding through the federal Head Start and Early Head Start programs to purchase schools and expand these services, while other schools are being demolished to either remove a deteriorating building from the community or build other community resources, such as an early education center. The second most prevalent entity was private education institutes, which have taken ownership of 39 closed schools, most commonly as charter schools for children. Repurposing vacant public schools as charter schools makes the most sense from a practical perspective, as converting one school into another presents relatively few obstacles. Other private education initiatives included professional career training for adults, after-school and summer programs, educational programs for at-risk youth, or theological training. We identified 38 rescued schools, that is, initiatives pioneered and organized by community-based organizations (CBOs) that are either a registered non-profit organization or in the process of becoming a registered non-profit organization and offer specific services to address local challenges within their community or for a target population within the community. Services offered at rescued schools vary widely, including arts and cultural programming, community kitchens and food banks, disaster relief and resilience hubs, job creation opportunities, medical clinics, community libraries, environmental programs, and psycho-social and educational services for children. Some of these organizations have been established for decades and moved into an abandoned school, whereas others utilized an abandoned school as an opportunity to create a new resource for their community. Rescued schools were identified throughout Puerto Rico, with a noticeable cluster in the Caguas municipality. Caguas has a relatively small population of 125,000, yet has 6 of the 38 identified rescued schools, which may be due to a larger number of abandoned schools and/or informal support networks among neighboring communities.

Less common, though more controversial, are private businesses that purchased abandoned schools. We identified twelve corporations that plan to either transform existing school buildings or demolish and rebuild new businesses on school property. While each school-to-business initiative remains a work in progress, plans for hotels, cinemas, nursing homes, shopping centers, and supermarkets have been identified in the media (

Ramos 2020). Finally, we identified five abandoned schools that were repurposed into churches, and three were categorized as “other” since we had insufficient information to categorize them.

3.2. Rescued Schools as Community Anchor Institutions

Interviews with rescued schools revealed how these initiatives can replicate and elevate the community anchor that the original school once provided. Here, vacant schools offer an energizing space to organize alternative social infrastructure that envisions and enacts community futures and addresses localized issues. Rescued schools initiate from the ideation and passion of community leaders, often parents and alumni of the closed school, and the kinds of programs and services offered in rescued schools are often a by-product of deep community engagement. For example, in the abandoned Carlos Conde Marin school in Carolina, Parceleras Afrocaribeñas, a non-profit organization, created the “la Conde” project to repurpose the school. The surrounding San Antón community suffers from an increasingly elderly population and creeping industrialization as their once-residential community on the outskirts of San Juan is being rezoned into an industrial area. The once-abandoned school was even designated as a landfill after Hurricane Maria. Through an extensive participatory design process with community members, Parceleras Afrocaribeñas facilitated a “community plan” that articulates a vision for how rooms in the school can be repurposed to create a space that promotes neighborhood creativity to trigger socio-economic opportunities. Thus far, this process has resulted in the creation of a community kitchen, a multi-use space for various programming, a fruit forest, and a resilience center. In a similar fashion, the abandoned Dr. Pedro Goyco school, located in the Santurce region, which is rapidly gentrifying as a result of a burgeoning visitor economy, enabled community leaders to organize and envision the school building as a hub that preserves and supports local arts and culture as the fabric of their community changes. This spurred the creation of a 501(c)(3) Taller Comunidad la Goyco, which repurposed the Dr. Pedro Goyco school to retain local culture and history while offering health and environmental services for the community. Currently, Taller Comunidad la Goyco offers free access to a community library, playground, kitchen space, and psycho-social therapy, among various education, culture, and health programs. They also serve as a central hub to meet and discuss pressing community issues, leading to broader activism and advocacy efforts. In rare cases, there have been contrasting community desires for how to repurpose abandoned schools. For example, the abandoned school of Emiliano Figueroa Torres in the Piñones neighborhood has been rescued by a collection of eight entities, each operating out of dedicated classrooms in the school. While this shared-space model has demanded higher levels of organization and coordination, it has offered a means for small community groups to productively utilize the school space while sharing the costs and labor involved in rehabilitating the school.

In rural areas of Puerto Rico, rescued schools serve as community anchor institutions by responding to challenges associated with increasingly elderly populations and the out-migration of young people, coupled with emergency preparedness and access to critical resources. For example, the MAMEY community center in Guaynabo and ID Shaliah in Canóvanas are both a 30–40 min drive from the nearest hospital. This prompted both projects to provide basic medical services such as a pharmacy and access to physician care. Fundación Bucarabón in Maricao and Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer in Adjuntas shared how one of their main priorities is to create job opportunities for community members. Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer created a marketplace enabling women to sell homemade products, whereas Fundación Bucarabón supports women empowerment opportunities through rural tourism, agricultural initiatives, and other economic opportunities. Responding to the increasing threat of hurricanes and other disasters has been a recurring theme in rescued schools. In the same way that schools serve as a place for shelter and resources during and after disasters, most rescued schools incorporate community resilience resources as a key function of their project, whether that includes access to solar power, potable water, food, or other emergency preparedness resources. For example, the Long-Term Recovery Group (LTRG) in Juncos has an infirmary and radio system to contact people across the island in case of emergency, coupled with a community kitchen to provide food and shelter during and after disasters. In addition to serving its own community, LTRG has begun working with neighboring communities to increase community preparation.

Beyond community-identified programs and services, rescued schools also increase social cohesion and community building. Many rescued school leaders attended the school they rescued and have strong ties to the physical space. These projects bring community members together through volunteer brigades to clean school property and support various initiatives. Moreover, rescued schools commonly serve as venues for workshops and other community events, spaces to discuss and address community development goals, or simply places for residents to spend time and socialize. Several projects, such as Taller Comunidad la Goyco and Coordinadora Paz para la Mujer, operate podcasts to build community by discussing local culture and pressing community challenges.

3.3. Challenges in Grassroots Adaptive Reuse

Despite the restorative value rescued schools offer, repurposing an abandoned school is a significant undertaking, particularly when left vacant for years. Interviews with members of rescued schools revealed three common challenges: legally acquiring school properties, obtaining sufficient and sustainable funding, and attracting continual volunteer support.

Securing ownership of school buildings is challenging when competing with more lucrative bids, as Puerto Rican government offices are interested in producing cost savings from school closures. The Department of Transportation and Public Works (DTOP) often asks for around USD 500,000 to purchase abandoned schools, which is an unrealistic sum for small grassroots organizations. Communication with DTOP and knowledge of competing interests in vacant schools is often an opaque process, and lease applications can take several years before receiving formal approval. A common experience shared among rescued schools is of community groups balking at the proposed price for the school when they already feel a sense of ownership of the school. Their ownership is expressed through existing school maintenance efforts and productively using the abandoned space coupled with framing the school as a public resource that should be returned to the community. Rescued school applications are typically made by community members whose families have attended the school for generations and propose utilizing the space to provide resources for the community that are often expected to be provided by the government. Through lengthy rounds of communication and advocacy, most rescued schools are granted a lease for 1–3 years for USD 1 per year to utilize the vacant school property productively. In some cases, community members claim ownership by occupying and repurposing the school property to produce facts on the ground before obtaining an official lease. These groups find it more effective “to ask forgiveness than permission” when dealing with overly slow and bureaucratic government entities. While quasi-legal occupancy and short-term leases offer a partial win for rescued school projects, without long-term leases or ownership, rescued schools remain in a tenuous position, having to continually prove they are productively using the school while there is a looming threat that a new entity will offer a lucrative bid at the end of their lease period, after they have invested labor, funds, hopes, and dreams into renovating the space.

Insecure ownership also inhibits structural renovations to improve building safety. A representative from Fe Que Transforma, which has repurposed an abandoned school into a resilience center, shared how DTOP made it clear that “they will take the school back if they are not actively doing something productive with the space”. Decision-making criteria for what “productive use” means and to whom are left open to interpretation. Several organizations have endured ongoing complications even after they obtained ownership, as obtaining permission to hook up water and electricity has encountered challenges with under-resourced municipal governments. The Taller Comunidad la Goyco project offers an exception, as they were able to successfully negotiate ownership of their school building using tactful political pressure, which eventually led to significant structural renovations through federal funding.

Like any start-up grassroots initiative, obtaining and sustaining sufficient funding to renovate schools and operate programs and services is a major challenge. Volunteer labor and in-kind contributions from within the community are the main resources that support rescued schools. Beyond internal support, rescued schools have achieved varying success in securing donations from community-based organizations, Puerto Rican foundations and NGOs, private businesses, and contributions from the broader Puerto Rican diaspora. In several cases, municipal governments have provided nominal support upon request, such as covering electricity and water costs, construction materials for renovations, and resources for community resilience centers such as solar panels, generators, water tanks, food, etc. These tend to be ad hoc, short-term arrangements. Thus, rescued schools tend to move as fast as available funding permits, often renovating and repurposing one room at a time. While most rescued schools are in the early phases of school repurposing, those that are further along have explored means to generate sustainable funding. For example, several rescued schools rent classrooms to artists and private businesses to generate baseline, predictable revenue to cover operating costs while also productively using classroom space within a large school complex. Overall, most community projects share ambitious visions for their project, but limited funding has slowed progress.

Since rescued schools operate and rely on the generosity of volunteers and community support, sustaining initial efforts and community buy-in has been a commonly cited challenge. Initial efforts to clean up debris and rubbish from an abandoned school attract exuberance and support from the community. However, repurposing schools is a major undertaking involving hard physical labor coupled with engineering, legal, and management insight and flexibility. Mobilizing and coordinating volunteers has become a significant undertaking. Several leadership members of rescued schools, such as the MAMEY community center, report initial excitement and desire expressed by the community to repurpose abandoned schools; however, recruiting volunteers to realize this vision has been underwhelming. Thus, rescued schools operating solely with ad hoc volunteers are in a precarious position. Several organizations have offered to hire community members on a part-time basis but still encounter challenges finding employees. In some cases, rescued schools have supported each other by coordinating volunteer brigades as a demonstration of solidarity toward similar community values.

4. Discussion

Puerto Rico’s mass school closures offer lessons and insight into the adaptive reuse literature along with societal shifts and competing visions for Puerto Rico’s future. In what follows, we describe how rescued schools offer an alternative, grassroots adaptive reuse model and make a case for why government authorities should explore and facilitate collaborative multi-actor partnerships that support community-based participatory initiatives to repurpose schools. We conclude by raising questions about how the outcome of Puerto Rico’s abandoned schools will be emblematic of competing political visions.

4.1. Rescued Schools as “Grassroots Adaptive Reuse”

Given the challenges involved in reselling and repurposing schools coupled with the magnitude of abandoned schools in Puerto Rico and the US more generally, it raises the question of what is the “right” thing to do with vacant schools. The adaptive reuse literature offers dozens of creative means to repurpose schools, which are often transformed into charter schools, multi-unit residential facilities, or businesses. However, the decision-making process to decide how and who will repurpose these community assets is typically conducted behind closed doors, as government-led committees that receive and assess competitive bids prioritize the highest bidder with a feasible proposal and rarely consult the community. The rescued school movement in Puerto Rico offers an alternative grassroots adaptive reuse model whereby local communities envision and enact productive ways to repurpose schools that improve the social, cultural, and/or economic well-being of their community.

Since schools serve as anchor institutions, holding the fabric of society together by providing a “third place” for residents to build relationships and critical support networks, we argue that government authorities should prioritize community visions to repurpose abandoned schools to restore a local asset. Community visions must be supported by collaborative partnerships between municipalities, community-based organizations, and other supportive actors. These partnerships will be uniquely shaped by each situation, with a commonality of drawing complementary abilities from each entity to transform and build a strong foundation for a new, long-lasting community anchor. In this sense, school repurposing efforts can enact new socio–government compacts between state and local governments and diverse community groups.

To support these efforts, school closures can be packaged with a succession plan that proactively explores community-based alternative uses as a point of departure and, if endorsed and energized by community members, build partnerships to provide an array of financial, managerial, and legal resources to support these initiatives. Our interviews with rescued schools revealed three main challenges they face in repurposing schools: legally acquiring school buildings, obtaining sufficient funding, and sustaining volunteer support. Collaborative partnerships can help address each of these. For example, rather than offering short-term leases, community groups selected to repurpose schools should be offered secure long-term leases or ownership of the property by the state to empower them to invest in long-term reconstruction efforts. Municipalities can play a role in offering financial contributions for service provisions that overlap with municipal responsibilities and, in some cases, take on managerial and ownership responsibilities if community-based organizations are still developing those capacities. Local civil society organizations can offer community connections, legitimacy, volunteer support, and other resources when rescued schools share overlapping missions. Foundations and philanthropic organizations external to the community can be solicited for various forms of grant support and expertise.

Government authorities anticipating cost savings from school closures should provide a reasonable start-up funding package for grassroots adaptive reuse projects. School closures are regularly justified by government officials to improve cost efficiency, yet the cost calculations are rather narrow, typically measured in standardized academic performance metrics and school enrollment. Moreover, the projected revenue from the sale of school buildings is often unrealistically high (

Dowdall 2015). The broader tangible and intangible value schools provide communities remain absent from decision-making criteria, leading to unconsidered consequences that abandoned schools can have for communities. The potential value rescued schools can provide their community is often unconsidered or undervalued when there is competition from other bidders. For example, Taller Comunidad la Goyco estimates that they have provided over USD 500,000 annually in free services to their community, offering many health, environmental, and cultural programs and resources that often should be provided by the government. If school closures are projected to save money, then a significant portion of those savings should be allocated to productively reusing the building to support the community. Beyond repairing a lost community asset, financially supporting rescued schools will increase the probability that the school building will not devolve into a blighted property, which can cause neighborhood dereliction and, potentially, future maintenance costs.

Certainly, not all closed schools will be suitable for grassroots adaptive reuse. In some cases, selling a vacant school to a developer to be repurposed into a cinema or supermarket, for example, might be the most viable use and provide something valued by community members. Passionate community champions, a broadly endorsed, feasible vision, and collaborative government–civil society partnerships are critical to repurpose schools for the common good. If a suitable grassroots adaptive reuse initiative can not be identified, then government officials can confidently move on to solicit proposals from other entities, maintaining a “repurposing committee” of community members to vote on potential buyer plans to purchase and repurpose the school, as demonstrated in Kansas City and Philadelphia (

Dowdall and Warner 2013).

4.2. Abandoned Schools and Puerto Rico’s Future

Abandoned schools and their reuse are emblematic of broader societal shifts and clashing political priorities in Puerto Rico. In

Naomi Klein’s (

2018) The Battle for Paradise, she frames a broader battle for Puerto Rico as the clash of two dreams, each with fundamentally opposing objectives—one dream is the desire for citizens to exercise collective sovereignty over national resources, the other is the desire for a small elite to evade government reach and accumulate mass profit. Within the context of hurricanes and austerity cuts, Puerto Rico’s abandoned schools have become contested sites. The proliferation of abandoned schools demonstrates failures in education reform and opens new spaces for resistance and alternative social infrastructures to emerge. Public schools are perceived by many residents as community-owned critical resources that must remain within and for communities to support local development efforts, whereas external pressures from private businesses and government offices envision closed schools as opportunities for privatized education reform through charter schools and voucher systems while facilitating opportunities to advance visions for a visitor economy as a part of its economic development strategy. This vision has included creating new tourist attractions, improving infrastructure, and building new resorts. In different ways, school closures have played a key role in this urban renewal vision. For example, the Dr. Pedro Goyco School was located along Calle Loiza, near beach-front property that is rapidly gentrifying with the increase in restaurants and bars coupled with short-term housing rentals. While the Dr. Pedro Goyco school was open, a municipal ordinance prohibited bars and nightclubs from being located within a short distance of the school. Shortly after the school closed, several bars set up businesses close to the school, leading residents to question the government’s motives for closing the school in the first place.

The magnitude of abandoned schools throughout Puerto Rico and ensuing decisions on how to repurpose these properties, if at all, presents an active space of contestation for how Puerto Rican society will be restructured in a post-austerity context. Currently, hundreds of schools are left vacant throughout Puerto Rico, leading many to wonder about the future development plans for these sites. Decisions on the adaptive reuse of abandoned schools become emblematic of the broader crossroads Puerto Rico faces as it shifts toward a visitor economy. The repurposing of schools is another entangled layer. The future use of Puerto Rico’s abandoned schools will reveal the ways in which the Puerto Rican government envisions its future, which dreams it will pursue, and how residents will respond and resist.