Abstract

Hollywood will encounter some cultural policies when its films are imported to the Chinese film market on a revenue-sharing basis. These include a quota system, a censorship system and an uncertain release schedule. However, China has been the fastest growing film market since 2008 and the second largest film market in the world since 2012 (yet the current film industries worldwide are recovering from the impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic). Despite the restrictive cultural policies, Hollywood, attracted by the promising profitability, have incorporated more Chinese roles and more plots about China to please the Chinese film regulators and audiences in order to gain access to the lucrative Chinese film market. Furthermore, the depiction of China has become more positive and diverse in recent Hollywood blockbusters compared with the Orientalist stereotypical images in the past. The author intends to examine the reasons behind the phenomenon through analysing the positively changing images of China from early Hollywood films to the recent Hollywood blockbusters. In fact, the positively changing depiction of China illustrates China and the US negotiating the dynamic process of cross-cultural exchange in economic and political terms through compromise, competition and collaboration.

1. Introduction

China and American films have long been entangled together since the 1920s, and China has always been one important target market for Hollywood’s global expansion. After the foundation of the PRC, Hollywood films were removed from China for a period due to different ideologies. However, China implemented the Reform and Open-up policy in 1978 and the US and China established diplomatic relations with each other in 1979, thus, the US started to promote Hollywood films to China again, even though in the name of cultural exchanges or on a very small scale. Until the beginning of the 1990s, due to so many years of institutional problems in the Chinese film system, the Chinese film market was on the verge of collapsing. Hollywood waited for the opportunity. As one aspect of the reform in the Chinese film system and one method to revitalise the collapsing Chinese film market, Chinese authorities decided to introduce 10 foreign films on an internationally agreed revenue-sharing basis each year from 1994. Most of the foreign films were from Hollywood. Thus, the quota system for importing Hollywood films was established. The quota was doubled due to China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 and enlarged to 34 films per year based on the signing of the China–US Memo of Understanding regarding theatrical film releases in 2012.

Besides the quota system, in order to have access to the Chinese film market, Hollywood films need to encounter another two cultural policies, the censorship system and uncertain film release schedule. Because China does not have a film-rating system, all the films need to be censored to be suitable for all audiences of all ages before distribution and exhibition. And Hollywood producers need to coordinate the film release schedule with the Chinese film-regulating sector and their importers.

With the further reform of the Chinese film system and the growth of the Chinese film market, China has been the fastest growing film market since 2008 and the second largest film market in the world since 2012. Hence, despite the restrictive cultural policies, Hollywood, attracted by the promise of increasing revenue, has developed many strategies of incorporating various Chinese elements to please the Chinese film regulators and audiences to gain access to the Chinese film market in recent years. Furthermore, the images of China displayed in the recent Hollywood blockbusters are shifting to become more and more positive compared with the Orientalist or stereotypical images in the earlier Hollywood films.

This paper will first examine the changing process of the images of China in Hollywood films from the early 20th century, aiming to illustrate the reasons behind the positively changing representation of China in recent Hollywood blockbusters compared with the stereotypical and Orientalist images in the past. Joseph Nye’s analysis of soft power will offer a helpful theoretical framework to evaluate the complicated interplay between China and Hollywood in terms of cinematic or cultural representation, commercial profits and political concerns.

In the 1990s, Joseph Nye developed the concept of “soft power”. () claims that “soft power is the ability to affect others to obtain the outcomes one wants through attraction rather than coercion or payment” (p. 94). () contends that “hard power can rest on inducements (‘carrots’) and threats (‘sticks’). Soft power rests on the ability to shape the preferences of others” (p. 5). He goes on to note that “hard power and soft power are related because they are both aspects of the ability to achieve one’s purpose by affecting the behaviour of others… The types of behaviour between command and co-option range along a spectrum from coercion to economic inducement to agenda setting to pure attraction” (), as the following Table 1 illustrates.

Table 1.

Power ().

Coercion normally represents hard power, while pure attraction represents soft power, but they are not extreme opposites; the two concepts range along a spectrum, with a gradual transition from one pole to the other. In this sense, neither hard power nor soft power is absolute, and the distinction between the two is one of degree.

2. Images of China in Early Hollywood Films

In early Hollywood films, most Chinese characters were presented as uncivilised, backward, ignorant, deceitful or treacherous, or not even played by actors of Chinese descent. In general, Chinese roles were people of low classes, villains or prostitutes.

The negative portrayal of China and Chinese people is greatly associated with two historical events. Genghis Khan’s looting hordes conquering from central Asia to Eastern Europe in the 13th century provides the origin of the Yellow Peril stereotype for Westerners. () holds the view that the Yellow Peril is “rooted in medieval fears of Genghis Khan and Mongolian invasions of Europe, [and] the Yellow Peril combines racist terror of alien cultures, sexual anxieties, and the belief that the West will be overpowered and enveloped by the irresistible, dark occult forces of the East” (p. 2). The second source for the negative image of China as a backward country was the decline of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) in the late 19th century. After the Industrial Revolution, many Western countries, as well as Japan, stepped onto the road of modernisation, while the Qing government still stuck to the old feudal governing concepts, unwilling to reform the political system fundamentally. China was no longer the strong and prosperous country it had been in ancient history. In 1840, through the first Opium War, China’s gate was forced open by the powerful boats, guns and cannons of Western invaders. Since then, the Qing government was defeated by various Western countries, signed many unequal treaties, and was forced to open the trade ports and allow foreign traders, diplomats and missionaries into China. Thus, the image of China and the Chinese people as backward, hidebound, conservative, ignorant and vulnerable was spread in the West. In the meantime, out of dissatisfaction towards the Qing government’s rule and the foreign invasion of China, various uprisings emerged, such as the Taiping Rebellion (Taiping Tianguo Revolution) and the Boxer Rebellion (Yihetuan Movement). The series of uprisings in the late Qing Dynasty emphasised the image of the Yellow Peril, originating from the fear of the West towards the Mongolian invasion of Europe, and reinforced the stereotype of the Chinese people as evil and brutal. The negative characterisation of China and Chinese people has been reinforced under this historical backdrop.

After the Qing Dynasty was overthrown in 1911, the Republic of China was established. However, the newly born regime was quite fragile, and China fell into turmoil again due to warlordism, and there were also other conflicts including the resistance war against Japanese invasion and the civil war between the Communist Party of China (hereinafter CPC) and the Kuomintang (hereinafter KMT) over the following three decades. During this period, a large number of missionaries came to China and sent back accounts about China to their own countries, which became an important channel for foreigners’ knowledge about China. Their stories containing a backward, feeble, impoverished image of the Chinese people in the late 19th century exerted a profound influence on the West. The information sent back by the missionaries, () contends, “did more to give form to the American image of China than all the other factors combined” (p. 3). () expresses a similar opinion that the missionaries who went to China “placed a permanent and decisive impress on the emotional underpinning of American thinking about China” (pp. 67–68).

Furthermore, beginning in the 1840s, a large number of Chinese labourers were attracted by the Gold Rush and flocked to California as well as other Western countries like New Zealand. Because the Chinese labourers worked harder and longer and asked for less payment than any other group, the local white populations there feared for the jobs taken by the Chinese labourers and feared for miscegenation with the Chinese people, which provoked the hostile attitudes of Americans toward the Chinese. As () remarks, “the yellow peril became a flood of cheap labour threatening to diminish the earning power of white European immigrants” (p. 2). In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act was implemented, prohibiting the immigration of Chinese labourers to the United States, which reinforced the negative impressions of Americans about Chinese people. As () contends, “the Orient is not only adjacent to Europe; it is also the place of Europe’s greatest and richest and oldest colonies, the source of its civilizations and languages, its cultural contestant, and one of its deepest and most recurring images of the Other” (p. 1). Therefore, China and the Chinese appeared on the screen only as a misread image of “the Other”, which contrasted with the positive images of the civilised and rational West.

Under this disadvantageous background of racial discrimination in the United States, Chinese roles in Hollywood films could only be played by non-Chinese actors and actresses; for instance, in films like Broken Blossom (directed by D. W. Griffith, 1919) and The Good Earth (directed by Sidney Franklin, 1937), Chinese characters were played by white actors or actresses who were made up heavily. Yet, the film Good Earth is a little bit different, owing to having depicted industrious and pristine Chinese peasants, which changed China’s uncivilised and backward stereotypes in the eyes of Western people at that time to some extent.

The most representative and notorious characters in this period were Fu Manchu and Charlie Chan. Fu Manchu originally appeared in a series of novels created by an English author named Sax Rohmer, and went on to feature in many films, television shows and comics in the early 20th century. In films, he wore a dark, long robe associated with the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912). He was bald, tall, thin and high-shouldered, with long thin eyes, arched eyebrows and two tufts of a drooping moustache. He was depicted as a mysterious, sinister, treacherous, cunning, vicious and brutal scientist who had mastered Western science and Eastern mysterious magic and conspired to destroy Western civilisation. Rohmer had created the most visible and recognisable Yellow Peril stereotype in the eyes of Westerners, and the image of Fu Manchu has exerted a profound influence on the subsequent characterisation of Chinese people in Western films. During the same period, American writer Earl Derr Biggers created a character, Charlie Chan, who was, in many ways, the opposite of Fu Manchu. Charlie Chan was a benevolent, intelligent and heroic detective from the Honolulu police. He featured in dozens of films that were popular with American audiences. Some critics thought Charlie Chan offered a positive image compared with the evil, stereotypical Fu Manchu. However, some Chinese American critics, like (), argue that “Charlie Chan embodies the stereotypes and stigmas of Chinese Americans, particularly of males: smart, subservient, effeminate” (p. 211). Although the character of Charlie Chan is much more positive than Fu Manchu is, it still reinforces another stereotype, that of subservient Chinese or Asians. In addition, within the context of racial discrimination and anti-miscegenation at that time in America, Fu Manchu and Charlie Chan were never played by Chinese actors: Fu Manchu was always played by white actors, while Charlie Chan was originally played by Japanese or Korean actors, but the characters in the films were minimised. According to (), the film series achieved success until a white actor started to play the role of Charlie Chan.

However, there was one sole exception, Anna May Wong, who became the first Chinese American actress in Hollywood. Although she was a breakthrough for Chinese performers, due to the severe racial discrimination and prejudice at that time in America, her roles in films could only be either the tragic Oriental charmer who fell in love with a Euro-American man but had to commit suicide due to the fear for miscegenation, like Lotus Flower in The Toll of The Sea (directed by Chester M. Franklin, 1922), or the seductive, conniving Chinese American girl who desired to be a white girl and win the love of a European or an American man, like Annabelle Wu in Forty Winks (directed by Paul Iribe & Frank Urson, 1925). Wong played the role of Fu Manchu’s daughter in Daughter of the Dragon (directed by Lloyd Corrigan, 1931), and became the prototype of the “Dragon Lady” for Chinese female roles in later Hollywood films. In addition, Anna May Wong played a Mongolian slave, Native American and Eskimo in Hollywood films; however, the destiny and character of these roles were quite similar, which did not provide much performance space for Wong. She had already been associated with stereotypical Chinese roles in Hollywood’s eyes, though she had earned some fame through these roles. She protested this phenomenon in an interview with British film journalist Doris Mackie: “You see I was so tired of the parts I had to play… Why is it that the screen Chinese is nearly always the villain of the piece?… Why should we always scheme-rob-kill? I got so weary of it all—of the scenarist’s conception of Chinese character…” ().

Thus, from the late 1920s to the 1930s, Wong shifted her performing career from America to Europe. European audiences were much more receptive to her performance and rewarded her with more applause than in America. Moreover, she went to China in 1936 for the first time and stayed there for almost a year to learn Mandarin and experience the real China. In the past, because of Wong’s Chinese heritage, she could not secure any female Asian protagonist roles from Hollywood, only the pathetic or treacherous Orientalist roles. She had been trapped in the contradiction between her own racial identity and her national identity. However, the stay in Europe and the experience in China made Wong reconcile with her Chinese and American backgrounds. () notes that “she would attempt to use the fame she had earned through portraying stereotypical Chinese role to publicise the ‘real China’” (p. 94). In fact, in the late 1930s, Wong appeared in two films, Daughter of Shanghai (directed by Robert Florey, 1937) and King of Chinatown (directed by Nick Grinde, 1939). The former was quite an unusual Asian-focused film, with Asian performers in the leading roles instead of Euro-American actors cast in Asian roles. In the latter film, Wong played a physician who raised funds for the Chinese people suffering from war, which also embodied a positive representation of Chinese people. During World War II, she only acted in two films, Bombs over Burma (directed by Joseph H. Lewis, 1942) and The Lady from Chungking (directed by William Nigh, 1942), both demonstrating the Chinese people’s heroic deeds against the Japanese invasion. Meanwhile, Wong devoted most of her time to raising goods and funds to support the Chinese people’s resistance against Japan by means of her fame and influence. However, that Wong could represent the positive picture of Chinese people in Hollywood films was in large part due to the relations between China and the United States. During World War II, Japan’s invasion of China and Chinese people’s resistance had won sympathy from the American public and brought about a positive depiction of China and Chinese people on the Hollywood screen. As () points out, “Hollywood’s interest in positive portrayals of China reflected international relations with China rather than audience demand” (p. 66). China and the United States became allied against fascism, especially after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941. Nevertheless, apart from the alliance period between China and the US during World War II when the depiction of China and Chinese people tended to be positive, most of the rest of the time the representation was prone to be stereotypical and Orientalist.

In any case, no matter whether stereotypical or relatively realistic, the roles that Wong played have exerted a great and profound influence on the characterisation of Chinese people on American screens.

Over the following forty to fifty years, there were few changes in the way Chinese characters were represented in Hollywood films, but this situation shifted in the 1970s, when Bruce Lee began to break previous stereotypes of Chinese people as being weak and subservient or barbarous, untrustworthy, callous and devious. By means of the rising popularity of Kung Fu films, Western audiences discovered that the Chinese could also be kind, powerful and righteous; however, the success of Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan and Jet Li, as positive a phenomenon as it may be, has reinforced another popular stereotype of the Chinese as Kung Fu masters. Especially, after the huge success of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (directed by Ang Lee, 2000), even the character design of Chinese actresses came to be associated with Kung Fu skills, as evident with Zhang Ziyi in Rush Hour 2 (directed by Brett Ratner, 2001) and Lucy Liu in the Charlie’s Angels (directed by McG, 2000 & 2003) series and Kill Bill (directed by Quentin Tarantino, 2003 & 2004). In the first decade of the 21st century, there were no revolutionary changes in the diversity of Chinese characters. After successfully playing a Kung Fu master in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Chow Yun-Fat played an antagonist captain in the Singaporean area in Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (directed by Gore Verbinski, 2007), and his image in the film was a copy of Fu Manchu with the representative two tufts of a drooping moustache. Meanwhile, Jet Li played the cruel Dragon Emperor in The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor (directed by Rob Cohen, 2008). These roles still conform to the stereotypical features of Chinese people in the eyes of the Western audience as being evil, treacherous and scheming or skilled at Kung Fu.

3. Positive Image of China in Recent Hollywood Blockbusters

Military and economic power might often make others change their position, as the example of the United States shows. The American government can offer comprehensive support for the promotion of Hollywood films internationally through laws and policies, reinforced by its hegemonic position as an economic, military and political power. The American film industry is not only a powerful money-making machine but also a vehicle that conveys American lifestyles, ideas and values. () holds that “Hollywood uses cinematic images to inspire the dreams of both the American public and foreigners alike while also contributing to the international enhancement of the country’s soft power capacities” (p. 31). Most of the Hollywood blockbusters represent the US as a paradise for ordinary people to realise their own dreams through their efforts. Life in America is depicted as happy, full of freedom, and audiences around the world are yearning for it even though some of them have never been to the United States. This is the powerful enchantment of Hollywood.

However, in recent years, Hollywood has demonstrated how it has gradually changed its attitude toward all things concerning China due to China’s increasing economic and political power. Hollywood’s pursuit of commercial profit, to some degree, has counteracted the ideological differences between China and the United States. Due to the lucrative economic interest, political concerns can be downplayed. Thus, the images of China in Hollywood blockbusters have been changing gradually to the laudatory way.

In X-Men: Days of Future Past (directed by Bryan Singer, 2014), one of the mutants, Blink, who can create portals to teleport subjects, was played by a popular Chinese actress, Fan Bingbing. Although she only made a cameo appearance—her screen time was only a few seconds against the backdrop of a Chinese temple in the beginning of the film, and she only had one line—this character can be considered a breakthrough from the stereotypical role of antagonist or Kung Fu master, as she is cast as a superhero, an unimaginable role in the past.

Transformers: Age of Extinction (directed by Michael Bay, 2014) includes a more diverse range of Chinese celebrities, though most of them make only cameo appearances in the film. The righteous and brave boxer in the elevator is played by Zou Shiming, a genuine world champion in boxing, the second-hand motor dealer is played by Hong Kong actor Ray Lui, and the musician in the car is played by popular singer Han Geng. The Minister of the Ministry of National Defence of the PRC also delivers a line in Chinese after he received the news that Hong Kong has been attacked by Galvatron and his drones: “我是国防部长,中央政府一定全力支援香港 (I am the Minister of the Ministry of National Defence of the PRC, and Chinese central government will definitely support and help Hong Kong with all-around methods)”. In addition, the female CEO of KSI’s Chinese facilities is played by renowned Chinese actress Li Bingbing (Figure 1). In the film, she is also multilingual, delivering her lines in English, Cantonese and Mandarin, and demonstrates her combat and high driving skills, as well as having graduated from the Police Academy before undertaking an MBA. Furthermore, the more modern side of China was represented in the film. As Beijing and Hong Kong are the main locations where the story takes place, landmarks like the National Stadium—the Bird’s Nest, National Swimming Centre—the Water Cube and Pangu Plaza in Beijing, as well as old buildings in Hong Kong, are displayed on screen. The headquarters of the Chinese facility in the film is located in Guangzhou, but the magnificent building is the Tianjin Grand Theatre in reality.

Figure 1.

Female CEO of KSI’s Chinese facilities.

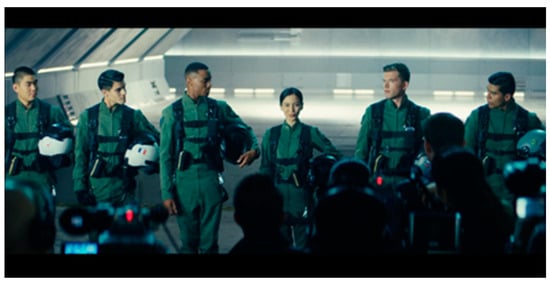

In Independence Day: Resurgence (directed by Roland Emmerich, 2016), which opened on 24 June 2016 in Chinese cinemas, Angelababy Yang, a very popular star in China, plays a Chinese female pilot and member of the International Legacy Squadron. At the beginning of the film, in the first appearance of the International Legacy Squadron, she stands in the middle of the squadron (Figure 2), an arrangement that indicates the significance of a Chinese pilot and, by implication, the Chinese film market. She also joins the counterattack against the aliens but is baited to enter the Alien Queen Ship together with the Earth Space Defence aerial fleet. She is one of the survivors after hijacking the aliens’ crafts and escaping from the Queen Ship, and one of the pilots who destroy the alien Queen in the end (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Chinese female pilot and member of the International Legacy Squadron.

Figure 3.

After winning the final counterattack against the aliens.

In Kong: Skull Island (directed by Jordan Vogt-Roberts, 2017), a biologist in the resource exploration team is played by a Chinese actress, Jing Tian (Figure 4). She explores the island for evidence of the monsters’ existence with the other leading members of the team, though she mainly takes a background role.

Figure 4.

Chinese female biologist in the resource exploration team.

Those films show that the representation of Chinese characters has changed significantly over the course of a century, shifting from lower class workers, peasants, villains, prostitutes and people with Kung Fu skills to the recent CEO of a high-tech company, a brave pilot participating in an international aerial fleet and a biologist in an exploration team on a wild island.

4. Positive Plots about China in Recent Hollywood Blockbusters

In addition to the specific Chinese roles appeared in recent Hollywood blockbusters, the plots about China in recent Hollywood blockbusters are also changing positively in the past decade.

The film 2012 (directed by Roland Emmerich, 2009) can be regarded as the pioneer high-concept blockbuster in Hollywood that incorporates a positive plotline about China. This film tells of an ordinary American family’s experience of seeking the Ark’s location to survive the catastrophic Mayan prophecy. The film topped the Chinese box office in 2009 (). Apart from the spectacular visual special effects and a thrilling plot, I believe the positive plot about China played an important part in drawing Chinese audiences into cinemas. Either displaying the Chinese Army’s rescue action after an earthquake, or setting China as the haven for human beings, the film offers a positive image of China, even as a saviour of the world, which is not a conventional view in Hollywood films. Thus, such a plot, despite being the selling point of the film, has stimulated the curiosity of Chinese audiences and motivated their national pride.

In an early scene in the film, a Chinese army official in charge of the rescue after an earthquake in Cho Ming Valley, Tibet, addresses the people waiting for evacuation in Chinese: “党和国家一定会帮助大家重建家园。” The English subtitle (“Party and country will assist in your re-location”) differs in translation from the Chinese line (“Party and country will help everyone rebuild your homeland”). The emotional resonance of the English subtitle is weaker than that of the Chinese line. The differences mainly lie in two translation choices. The first one is “大家 (dajia)”. The English subtitle just uses “your”, whereas in Chinese “大家” means everyone. “Everyone” emphasises all the people who have suffered in the earthquake, whereas “your” does not necessarily mean “everyone”. “重建家园 (chongjian jiayuan)”, should be translated as “rebuild or reconstruct homeland”, rather than “re-location”. The former translation sounds warmer and more sincere by offering the hope of new life to those who have lost their homes in the earthquake, while the latter translation is more impersonal and merely provides a sense of a secure future. In general, the Chinese line conveys more comfort to the people who have just experienced disaster. Furthermore, in China, whenever natural disasters or accidents that threaten the life and possessions of the public happen, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) will always rush to the front line to implement disaster rescue and relief. Therefore, a foreign audience with no background knowledge about this specific Chinese situation will not understand the full meaning of this line; it is particularly designed for a Chinese audience. Later in the scene, three Chinese army officers appear (Figure 5) who are in charge of recruiting volunteers to help in the rescue effort. They speak Mandarin with a little bit of a foreign accent (presumably something to do with the dubbing), and the extras playing the officers do not look quite righteous, but, compared with the vicious and cruel villains or the submissive maidens and prostitutes in early Hollywood films, the incorporation of high-ranking officers of the Chinese army could be regarded as a kind of positive representation.

Figure 5.

Three Chinese army officers.

In addition, when the protagonist opens the map of the Ark’s location, a map of China appears (Figure 6). Generally, in Hollywood disaster and superhero films, an American hero always saves humanity from danger or destruction in the end. Here, China’s Tibet is set as the construction base for the Arks, which are designed to save the survivors of the apocalypse. The Chinese are credited for making the reliable Ark for the human elite and other living species to survive the catastrophe, whereas, in the past, this kind of setting could not be imagined.

Figure 6.

The map of the Ark’s location.

Meanwhile, Tibet serves as the construction base for the Ark, a fact that deserves reflection and analysis. Tibet, the roof of the world, has always been a mysterious land for the Western world. () contends that “cinema has played a crucial role in spreading the exotic image of Tibet in the west. Not only has the explosive development of the mass media industry in the 1980s constructed Tibet into a part of the Western popular culture, but it has also strengthened the Orientalist discourse of Tibet on a global scale” (p. 15). () states that “on the one hand, it (Tibet) retained all its associations of being a paradisiacal Shangri-La; on the other hand, after China’s occupation in the 1950s, it also came to be viewed as a victimized land and culture laid waste by an invading colonializing power” (p. 8). For political and cultural reasons, European and American filmmakers have been interested in Tibet, especially in the last two decades of the 20th century, with films such as The Golden Child (directed by Michael Ritchie, 1986), Little Buddha (directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, 1993), Seven Years in Tibet (directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, 1997) and Kundun (directed by Martin Scorsese, 1997). The latter two films are ideologically loaded and convey strong anti-Communist messages. In those films, the Tibetan people and the Tibetan leader, the Dalai Lama, were depicted as the oppressed subjects of the Chinese government and the Chinese army. Although these films were not released in Chinese theatres, Brad Pitt, who played the leading role in Seven Years in Tibet, together with the director, Martin Scorsese, were still banned from entering China. Disney, whose subsidiaries, Touchstone Pictures and Buena Vista Inc., had been the production and distribution companies of Kundun, was also banned from conducting business in China. The Chinese government had such a strong reaction to the two films because the theme and purpose of the films were to criticise the Chinese government’s way of coping with the Tibetan issue and to support Tibet’s religious leader, the Dalai Lama, to separate Tibet from the PRC territory. The films commented negatively on the image of the Chinese government and meddled in the internal affairs of China at the level of film. Having made a negative interpretation concerning Tibetan issues, the films could not be accepted by the Chinese government. In the end, neither of the films performed as well in the North American film market as the producers had expected. () considers that the reason for the failure “lies in its clichéd Cold War narrative, which has long been at odds with the culture of globalization. The post-Cold War global market has been expecting new, apolitical discourses with universal values such as love, family, and friendship” (p. 22). The ideological conflicts have been magnified in those films, and run counter to the mainstream desire for peace and development in the international community and do not conform to the universal values in modern society.

In this context, it is noticeable that the film 2012 starts to shift tentatively the focus from ideological differences concerning Tibet to a depiction of current Chinese society that, while still being loaded with a conventional mind-set about China’s relationship with the developed countries of the West, generally portrays the Chinese government and the Chinese army in a relatively positive light. In an interview by (), Emmerich admitted that the initial ending was different from the one that appears in the film. After the catastrophic earthquake that struck Wenchuan, China, in 2008, he was moved by the stories of rescue and survival reported by the media and wished to express his respect for the Chinese people, so he decided to change the script so that China became the chosen land where all of humankind came together to confront a crisis and save the world. In fact, the comments from the director could be possibly considered as a publicity stunt, another form of promotion for the film, which verifies that Hollywood’s scales tend to tilt towards the profitability of the Chinese film market.

Hollywood can no longer ignore China’s cinematic influence and is thus faced with a difficult problem: how to achieve a balance between ideological and political differences and economic profits. But, it seems that, in recent years, the situation is shifting from ideological conflicts to economic interests. Especially since the 2010s, the positive images of China have been incorporated more and more often in Hollywood productions. In light of the rapid growth of the Chinese film market, the national box office revenue of China surpassed Japan, and China became the second largest film market in the world in 2012 and has remained the second largest film market since then. Hollywood has found greater market potential in China, and thus Hollywood blockbusters have started to incorporate plots and images of China that are more positive.

On 19 November 2013, Gravity (directed by Alfonso Cuarón, 2013) was released in China. The film demonstrates how a female American astronaut, Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock), returns to Earth after their space shuttle was hit by debris from a Russian missile. Due to the accident, only two astronauts, Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock) and Matt Kowalski (George Clooney), survive. The two make various attempts to reach the international space station, but Matt ultimately sacrifices himself to help Ryan reach Tiangong station, a Chinese space station, where she takes the Chinese spacecraft, Shenzhou, and finally returns to Earth.

China does not play the role of “World Factory” in this film, but is displayed, rather, as an advanced nation with cutting-edge astronautical technology. The Americans need support from China to get back to Earth by means of a Chinese space shuttle. The plot supports Joseph Nye’s point that “the distinction between them (hard power and soft power) is one of degree, both in the nature of behaviour and in the tangibility of the resources” (). He also believes that “a strong economy not only provides resources for sanctions and payments, but can also be a source of attractiveness” (). China has indeed made great achievements in the field of the astronautic and space technologies in recent years. In 2003, China’s first manned spacecraft, the Shenzhou-5, was launched, followed by another eleven manned spacecrafts in the following 20 years. Two space labs, Tiangong-1 and Tiangong-2, were launched in 2011 and 2016, respectively, along with six unmanned cargo spacecrafts from 2017. In addition, four Chang’e lunar probes have been launched since 2007; the Chang’e-4 probe became the first to land on the far side of the moon on 3 January 2019.

When promoting the film in Beijing, the director, Alfonso Cuarón, told Beijing Review, “When we were mapping out the story, we had to base it upon current elements in space”. Cuarón added, “We had the Hubble Space Telescope, the International Space Station, Tiangong station and a Shenzhou escape pod. That’s what was in space” (). Cuarón has denied deliberately pandering to the Chinese market, saying his storyline had nothing to do with winning over China’s film regulators and fans. Regardless of Cuarón’s denial, the reality is that he could not avoid the influence of the current international political and economic situation. At present, the United States, Russia and China are the only nations in the world that possess the technology for manned space flight, and the situation in the film justifies the arrangement between the Americans and the Chinese space station. Yet the producers cannot ignore the booming Chinese film market; the role that China’s space station and spacecraft play in the rescue mission accords with the preference of China’s film-regulating sector and increases the possibility that the film will be selected into the fixed screening slots for foreign films.

Besides the positive plot with regards to China, other Chinese elements appear in the film. These include the interior of the Chinese Tiangong Space Station, a floating ping-pong bat and ping-pong ball (Figure 7), and the Chinese spring onions being cultivated in the craft (Figure 8). When Dr. Stone prays for a safe return to Earth, a sitting Buddha figure is prominent on the top of a platform (Figure 9), a visual reminder that Asians normally will pray to Buddha for good fortune. Although Hollywood has tried to depict China with positive images, the ping-pong bat, Chinese spring onions and Buddha statue are still stereotypical conceptions about China (albeit in an updated form).

Figure 7.

A floating ping-pong bat and ping-pong ball.

Figure 8.

Chinese spring onions being cultivated in the craft.

Figure 9.

A sitting Buddha figure.

In The Martian (directed by Ridley Scott, 2015), too, which was released on 25 November 2015 in China, China was cast in a more positive light. Again, a Chinese space project helps an American astronaut, Mark Watney (Matt Damon), return to Earth safely. In a mission on Mars, the protagonist, Mark Watney, is presumed dead after a storm hits the space shuttle. However, he survives by means of ingenuity and courage and manages to send a signal to Earth that he is alive. Soon afterwards, NASA decides to launch a rescue action and works jointly with scientists around the world to rescue Mark. However, due to the destruction of NASA’s Iris supply probe, they have to figure out another solution. In the meantime, the China National Space Administration learns the news and offers its own classified booster rocket to NASA. Only China has the appropriate booster ready to complete the rescue mission successfully. At last, Mark returns to Earth with the help of the Chinese space programme, Taiyangshen.

However, despite the general similarities in terms of plot, there are some significant differences from Gravity. Here, the image of China is more concrete, positive and lofty. Firstly, the officials of the China National Space Administration, including the chief scientist and the deputy chief scientist, are granted considerable screen time. And they are played by a Hong Kong actor, Eddy Ko, and an actress from China’s Mainland, Chen Shu (Figure 10), respectively. They discuss whether to help the United States, as the Taiyangshen programme was prepared secretly and nobody knew of its existence. The deputy chief scientist thinks if China offers the booster to the United States, China’s Mars exploration programme will have to be terminated. However, for the sake of respecting human life, the chief scientist decides to offer help anyway. Secondly, as the rescue mission is broadcast live worldwide, people from all over the world know that Mark is returned home with the help of a Chinese space programme.

Figure 10.

The Chinese deputy chief scientist.

The film was adapted from a novel in which, in return for the help from the China National Space Administration, NASA included a Chinese astronaut on the next Ares mission. However, in the film, China learns about the stranded astronaut on Mars from the TV news; a decision is made to help the US on the Chinese authorities’ own initiative—“我们从航天的角度解决问题,寻求合作 (we will solve the problem from the perspective of aerospace, seeking cooperation)”—and an offer to save Mark’s life with the resupply rocket is made. It is clear at the end of the film that a Chinese astronaut was in fact included in Mission Ares V (Figure 11). Furthermore, together, the two Chinese scientists witness the successful launch of Ares V together with the American scientists in the film.

Figure 11.

A Chinese astronaut included in Mission Ares V.

Although the negotiation process is not presented explicitly in the film, a compromise has clearly been made. This detail can be analysed from different perspectives. On the one hand, the ideological conflict between China and Western countries is not the main theme in current global society. On the other hand, it was the Hollywood producers who decided to rearrange the plot concerning the deal between China and the US in the novel into cooperation between the two countries in the film, which embodies Hollywood’s intention to minimise the possibility of offending Chinese film regulators and Chinese audiences. Cooperation always looks loftier than deal making, which also accords with the general trend of win–win cooperation between the two countries.

The increased emphasis in The Martian on China’s strength in terms of aeronautics and astronautics, alongside the economic growth of the Chinese film market, shows how the influence and effects of hard power and soft power are mutually dependent and not necessarily separated by a distinct boundary. This factor could alter the attitude of the United States towards China. Nye’s thesis asserts that “the types of behaviour between command and co-option range along a spectrum from coercion to economic inducement to agenda setting to pure attraction” ().

The rising strength in the economy and scientific technology of China could reinforce its influence in terms of soft power on the US. Hard power can shift to the co-optive end of the spectrum of behaviour and transform into soft power. China has amassed hard power by means of the progress achieved in terms of manned astronautics. Evidence of this hard power can be seen in the plots associated with China in such recent Hollywood blockbusters as Gravity and The Martian. Furthermore, this hard power has been transformed into an expression of soft power in terms of the commercial profit of the US in the Chinese film market.

Even though the portrayal of a positive image of China in the plots of such films seems more like a commercial tactic employed by Hollywood filmmakers to pander to the newly booming Chinese film market, the fact is that Hollywood’s attitude towards China has indeed started to change. The images of Chinese people are quite different from those in early Hollywood films, which mostly were lower-class labourers and prostitutes, and cunning and sinister villains. A global audience has felt the enhancement of China’s international status by virtue of Hollywood’s prevalent influence on the world. From this perspective, China has benefited from the international dissemination of a more positive public image. () assert that “soft power is not a zero sum game in which one country’s gain is necessarily another country’s loss” (p. 22). In this case, it is a reciprocal strategy for both China and the US in which the two countries both achieve the outcomes that they want. China’s hard power is enhanced by means of the soft power of Hollywood films, for, as () claims: “Power always depends on the context in which the relationship exists” (p. 2). In the context of globalisation, the generation of cultural phenomena is always the result of a synergy of different forces that are inseparable from the changes of political and economic relationships between countries in the international community.

5. Conclusions

Almost half a century ago, Scratches on Our Minds: American Images of China and India was published in 1958, which was written by American political scientist Harold Isaacs. He conducted empirical research about images of China and India as perceived by Americans. In his study, Isaacs classified the American attitudes toward China along historic lines, depending upon the cultural and diplomatic relations between the two countries: “the Age of Respect (Eighteenth Century), the Age of Contempt (1840–1905), the Age of Benevolence (1905–1937), the Age of Admiration (1937–1944), the Age of Disenchantment (1944–1949) and the Age of Hostility (1949–)” (). In general, the turning points of America’s attitude toward China in different stages have aligned with the detailed historical information discussed at the beginning of the paper, such as the First Opium War in 1840, the breakout of China’s Resistance War against Japan in 1937, the end of World War II in 1945 and the founding of the PRC in 1949. This indicates that Sino–US relations will exert different impacts on the attitudes of the United States towards China, and further influence the images of China in the eyes of America. Just as () observes, “Americans have two sets of images, of which the modulation, with one advancing and the other receding alternatively, is tuned into the social and political atmosphere of the time. China is seen as both static and restlessly chaotic; the Chinese are both wise and benighted, strong and weak, honest and devious, and so on so forth” (p. 124). The United States will adjust the images of China in its own eyes based on its national requirements.

After the founding of the PRC, almost in the following two decades, due to the differences in ideologies between China and the United States, the two countries did not have any diplomatic contact until 1971, when Kissinger made his ice-breaking visit to China, and the Sino–American relationship started to change considerably. Afterwards, in 1972, President Nixon made his first official visit to China and signed the Joint Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America. Since then, the Sino–American relationship has entered a phase of normalisation. The Joint Communiqué of the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America came into effect in January 1979, and thus diplomatic relations were established between the two countries.

Just one year before the establishment of Sino–US diplomatic relations, China implemented the Reform and Open-up policy in 1978. Gradually, the status of China in the international community has been enhanced. China gained accessed to the WTO in 2001, and successfully hosted the Beijing Summer Olympic Games in 2008. In 2010, the World Expo was held successfully in Shanghai. In the same year, China overtook Japan in terms of GDP and became the second largest economy in the world. Thanks to rapid economic growth in China, the box office in the Chinese film market has increased 30% on average every year since 2008. The Chinese film market became the second largest film market in the world in 2012, despite the rate slowing in 2016 and 2017. Hence, as the preceding case studies show, the changes in the depiction of China and the Chinese in Hollywood films indicate that China’s development as an international power has exerted an influence on how its image is presented on screen.

Therefore, the changes in the representation of Chinese characters from a largely negative to a more positive image is closely related to the enhancement of China’s status in the international community, its rapid economic growth and the huge boom in its film market. These changes have also demonstrated Hollywood’s pragmatic strategies towards localising its cultural products to appeal to its target audiences and guarantee its long-term market share in the Chinese film market out of commercial considerations.

Nye contends that “the resources that produce soft power arise in large part from the values an organization or country expresses in its culture, in the examples it sets by its internal practices and policies, and in the way it handles its relations with others.” (). However, the resources also depend upon the economic strength, social cohesion and military might that guarantee incentives for cooperation and mutual exchange between nations. In this sense, neither hard power nor soft power is absolute, and the distinction between the two is one of degree. Sometimes, hard power is conducive for the exercise of soft power. Nye indicates that “a strong economy not only provides resources for sanctions and payments, but can also be a source of attractiveness.” (Ibid., pp. 7–8). Here, the parallels between the constant growth of the lucrative Chinese film market and the incorporation of positive Chinese elements into Hollywood blockbusters offer a clear example of soft power in operation. In this process, though China does not actively export its cultural soft power through its own domestic films, the tremendous profitability of the Chinese film market has inspired and attracted Hollywood productions to incorporate Chinese elements spontaneously to win the opportunity to gain access to the profitable Chinese film market. The whole process can be interpreted as a kind of indirect conversion of China’s hard power (economic development) into soft power. It is an effective method for Hollywood to win the opportunity to gain more box office revenue; meanwhile, China can make use of the opportunity to modify its previous Orientalist image and to demonstrate its cultural soft power to the rest of the world through Hollywood’s global influence.

Though the characters or the positive plots about China analysed before have little screen time, we still can observe changes and improvement in terms of breaking previous stereotypes of the Chinese. In light of the growth of the Chinese film market, these changes indicate that Hollywood has made a compromise in its desire for bigger commercial profits by means of demonstrating an image of an advanced and modernised China in order to please Chinese film regulators and gain access to the Chinese film market.

() holds that “in the case of American perceptions of China, screen images bear on a relationship between two countries—that is, China and America—that is as deeply problematic as it is critically important” (p. 1). As shown through the analysis in the previous sections, whether the portrayal of China and Chinese people is negative or commendatory relies much on the relationship between China and the United States. Owing to the thriving film market in China and the increasingly outstanding performance of China’s domestic blockbusters, Hollywood has been attaching more importance to the Chinese film market and film collaborations with China. As Hollywood would like to increase its share in the Chinese film market, it cannot afford to make films that the Chinese authorities or the Chinese audiences would not receive favourably. Thus, China has begun to have more initiative and discursive power about how China and Chinese culture are represented during the process of China–US film communications. This means it is necessary for Hollywood to see China objectively, equally and comprehensively, to explore Chinese culture in depth and to incorporate it into its films appropriately and compatibly, and that China has more opportunities to communicate realistic images of China, Chinese people and Chinese culture to overseas audiences and to change the Orientalist stereotypes commonly held by Western people.

However, in 2018, unexpected trade tensions between China and the United States broke out. In fact, according to the China–US MOU, China and America were supposed to start a new round of negotiations about importing foreign films after 2017. However, with the escalation of China–US tariff trade tensions from March 2018, negotiations over the quota and other policies concerning importing Hollywood films were stalled. In fact, since February 2017, American trade representatives had been in talks with the Chinese side to hammer out a deal about enlarging the quota of foreign films. Nevertheless, the escalating trade conflicts have damaged the potential for this happening. Besides, from the end of 2019, film industries worldwide have been suffering from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although film industries are recovering from the impact of COVID-19, the tensions of China–US relations in terms of technology and trade have not been improved much, thus, the two sides do not have much film cooperation recently.

Although the ups and downs of this relationship in terms of the economy and politics will exert an impact on their collaborations in the culture industry, the two biggest film markets in the world definitely will have more collaborations and the two sides will grow further interdependent with each other in the future. Until then, the complicated interplay between the two countries will go through various cycles regarding their economic and cultural co-operations. However, it is not a pessimistic trend, and, in the process, both sides can obtain what they need respectively through compromises, communications, competitions and collaborations.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Balio, Tino. 1995. Grand Design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Box Office Mojo. n.d. Chinese Box Office for 2019. Available online: http://www.boxofficemojo.com/intl/china/yearly/?yr=2009&p=.htm (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Greene, Naomi. 2014. From Fu Manchu to Kung Fu Panda: Images of China in American Film. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Guiyou. 2006. The Columbia Guide to Asian American Literature Since 1945. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs, Harold. 1958. Scratches on Our Minds: American Images of China and India. New York: The John Day Company. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, Karen J. 2005. The China Mystique: Pearl S. Buck, Anna May Wong, Mayling Soong, and the Transformation of American Orientalism. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yan. 2009. Haolaiwu Zainanpian Xinjieju: Zheci Lundao Zhongguo Zhengjiu Shijie (New End of Hollywood Disaster Films: It is China’s Turn to Save the World). ifeng.com. Available online: http://news.ifeng.com/society/2/200911/1113_344_1433414.shtml (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Lovric, Bruno. 2016. Soft Power. Journal of Chinese Cinemas 10: 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, Gina. 1993. Romance and the “Yellow Peril”: Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nye, Joseph. 2004. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics; New York: Public Affairs.

- Nye, Joseph. 2008. Public Diplomacy and Soft Power. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616: 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, Joseph, and Jisi Wang. 2009. Hard Decisions on Soft Power: Opportunities and Difficulties for Chinese Soft Power. Harvard International Review 31: 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 2003. Orientalism, 25th Anniversary ed. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Schell, Orville. 2000. Virtual Tibet: Searching for Shangri-La from the Himalayas to Hollywood. New York: Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Bai. 2013. China to the Rescue: Hollywood Blockbuster Gravity Reveals the Rise of China’s Soft Power. Beijingreview. Available online: http://www.bjreview.com.cn/print/txt/2013-12/09/content_583043.htm (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Varg, Paul A. 1973. The Closing of the Door: Sino–American Relations, 1936–1946. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Hongmei. 2014. From Kundun to Mulan: A Political Economic Case Study of Disney and China. Asian Network Exchange 22: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Longxi. 1988. The Myth of the Other: China in the Eyes of the West. The University of Chicago Press Journals 15: 108–31. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).