Abstract

This paper charts the journey from classroom-based training delivery to hybrid and virtual learning opportunities used to overcome the challenges imposed by public health restrictions introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The public health measures introduced in March 2020 had a significant effect on the ability of the Children First Information and Advice Service (CFIAS), in Tusla, Ireland’s Child and Family Agency, to deliver services. One of the key tools used by the CFIAS to support understanding of responsibilities, and best practice, in child safeguarding by professionals, and within organisations, has been the provision of direct training and information sessions. The introduction of public health restrictions necessitated a complete rethink by the CFIAS on how child safeguarding training and information are delivered. The paper presents an outline of the background and context of child safeguarding in Ireland, followed by a description of some of the challenges experienced by the CFIAS in response to the pandemic public health restrictions. It includes discussion on strategies and solutions considered to overcome these challenges. There is further discussion on the tools and methods eventually used, followed by a reflection on lessons learned by the CFIAS in areas including training delivery and methodology, eLearning, and information provision. The paper provides an analysis of limited qualitative and quantitative data, as well as a reflection on the lived experience of the CFIAS team members responding to the challenges posed during this time period, rather than a preplanned research study on pedagogical approaches in adult learning.

1. Introduction

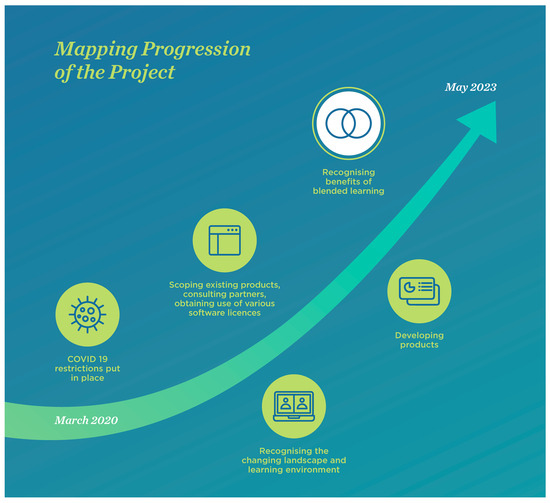

This paper describes the journey of the Tusla Children First Information and Advice Service (CFIAS) to understand and adopt technological solutions to overcome challenges posed by public health restrictions introduced in response to the COVID-19 global pandemic (see Figure 1, below).

Figure 1.

Map of the journey from start of pandemic to May 2023.

The Tusla CFIAS is a small team (n = 11) which supports best practice in child safeguarding in organisations across Ireland. The CFIAS supports individuals and organisations which work with children and their families, Government departments, and other umbrella bodies to understand their responsibilities under Irish legislation and policy to help keep children safe from harm. This is carried out through the publication of guidance and information documents, review of organisational policy documents, and facilitated training.

Tusla—Child and Family Agency (hereafter Tusla) is the “dedicated [Irish] State agency responsible for improving wellbeing and outcomes for children” (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2023a). Established in 2014, it supports and promotes the development, welfare and protection of children, and the effective functioning of families (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2021). It provides services in the following areas: child protection and welfare services; educational welfare services; psychological services; alternative care; family and locally based community supports; early years services; domestic, sexual and gender-based violence services.

Limitations of This Project Report

This paper provides an analysis of limited qualitative and quantitative data, as well as a reflection on the lived experience of the CFIAS team members responding to the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, rather than a preplanned research study on pedagogical approaches in adult learning. The findings and recommendations, presented in Section 7, are based on the limited data available and experiential learning from the CFIAS.

2. Background Context to Child Safeguarding Supports in Ireland

2.1. Child Safeguarding in Ireland

The child safeguarding landscape in Ireland has been changing and developing over the past 25 years. In September 1999, the Irish Government published Children First—National Guidelines for the Protection and Welfare of Children. These guidelines were based on a growing public awareness of child abuse as a societal issue and were formed largely by the recommendations of a number of inquiries into serious cases of child abuse1 (Department of Health and Children 1999).

With the publication of the first high-profile public inquiry into a case of serious child abuse in Ireland—the Report of the Kilkenny Incest Investigation (McGuinness 1993)—awareness of child abuse began to seep into the wider public consciousness. The recommendations, around transparency, accountability, inter-agency cooperation, training, and professional and corporate responsibility, from the Kilkenny case (McGuinness 1993) and the four high-profile public enquiries that followed helped to significantly shape the Children First National Guidelines (Department of Health and Children 1999). The Children First National Guidelines contained definitions of child abuse, reporting procedures, and protocols for all organisations that work with children.

There was a strong emphasis in these guidelines on the importance of inter-professional cooperation and communication in the detection and prevention of child abuse (Department of Health and Children 1999). This is clearly in line with lessons from not only Irish but also international child abuse enquiries (McGuinness 1993; Reder et al. 1993; Kelly 1997; Buckley 1998; Buckley 2000).

The Children First National Guidelines were updated in 2010, and again in 2017. In 2015, the Irish Government published the Children First Act (36/2015). The Act, inter alia, placed the guidance on a statutory footing (s. 6), created mandated reporting for certain categories of persons, and placed a statutory responsibility on organisations providing services for children to have certain policies and procedures in place.

2.2. Service Provision by CFIAS

One of the key tools used by the CFIAS to support understanding by professionals, and within organisations, has been the provision of training and briefing programmes. From 2001, a two-day training was offered at a local, regional, and national level which explored definitions of abuse, values and attitudes to child abuse, policies and procedures to create safer environments for children, and safe practice in working with children and young people. Over the years, the CFIAS reshaped and reworked the learning opportunities offered, based on review and evaluation with stakeholders, participants, and trainers.

2.2.1. Train-the-Trainer Programmes and Strategies

To build capacity, in 2005, the CFIAS introduced a train-the-trainer programme, in partnership with the Volunteer Development Agency of Northern Ireland and the Open College Network Northern Ireland (OCN NI). Between 2005 and 2013, Tusla (then the Health Service Executive) developed a cohort of over 50 trainers, in a wide range of community, voluntary, and statutory organisations. These trainers provided child safeguarding training both within their employing organisations and on behalf of Tusla.

2.2.2. Training Standards/Learning Outcomes

In 2016, Tusla set out to develop its own evidence-informed training standards and learning outcomes (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2016, unpublished). An excerpt, entitled Best Practice Principles for Organisations in Developing Children First Training Programmes (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2017), was published to accompany the 2017 edition of the Children First National Guidance. This document covered two basic levels of training, namely: Introduction to Children First and Implementing Children First (induction). Other standards and learning outcomes (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2018) developed by Tusla for advanced and additional learning opportunities were left unpublished but were circulated to organisations as needed.

2.2.3. Training and Learning Programme Development

Building on the learning outcomes and standards, the CFIAS identified and categorised three levels of training recipients (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2018, p. 5):

- All people who work in organisations that have access to or contact with children or provide services to children and families2;

- Those who work directly with children and families, or staff working with adults who for a range of reasons may have difficulties meeting their children’s need for adequate care and protection;

- Designated Liaison Persons (DLPs) and Deputy DLPs in organisations that work with children and families, or working in organisations that work with adults who for a range of reasons may have difficulties meeting their children’s basic needs for safety and security.

It was recognised that some individuals would need to complete training at multiple levels, leading to a cumulative acquisition of knowledge and skills. For example: staff working directly with children would need to complete training at level 1, before progressing to training opportunities at level 2.

The CFIAS developed training programmes and additional learning opportunities, which were provided as part of the statutory services of Tusla, to help organisations be safer places for children, help mandated, and non-mandated persons, better identify children at risk of harm or in need of support and protection, and facilitate better-quality reporting and cooperation between those working with children and Tusla. These included a one-day Foundation Training and one-day Designated Liaison Person Training (for people with leadership roles in child safeguarding), as well as a number of shorter briefing programmes and workshops.

3. COVID-19 Pandemic and Public Health Measures’ Impacts on CFIAS Service Provision

3.1. Start of COVID-19 Pandemic

On 12 March 2020, it was announced that schools, colleges, and other public facilities in Ireland would be closing that evening (Vradkar 2020). Additional measures followed, with the first “stay at home” order issued on 27 March 2020, initially for a two-week period (Carroll 2020). Restrictions were extended a number of times, with public gatherings generally banned between 27 March 2020 and January 2022 (Horgan-Jones et al. 2022). Even after restrictions had been lifted, many people remained reluctant to re-enter closed spaces with groups of people.

3.2. Impact on CFIAS Service Provision

The impact of the public health measures on the ability of the CFIAS to deliver its services was significant. There was a lack of ICT infrastructure to support remote working or meetings. All face-to-face training events were cancelled, and it was difficult to foresee when they would be re-instated.

A priority for the CFIAS was to establish whether there were quick fixes which could be applied to continue service delivery, particularly around training and information provision related to national child safeguarding legislation and policy.

A particular challenge posed by the fluidity and uncertainty of the public health restrictions was the ability of the CFIAS to plan and develop proposed solutions based on limited information, as well as unknown and constantly changing factors. This disequilibrium was a stressor for the team in terms of agreeing and developing concrete solutions to meet evolving needs.

3.3. Strategies Considered to Overcome Challenges Posed by COVID-19 Restrictions

There was significant internal discussion and exploration of strategies which could be used to overcome the challenges posed by the public health restrictions. As a service, the CFIAS had limited expertise in the IT field. A few team members had cooperated in an inter-agency project with a content design company to develop a universal eLearning module (HSE and Tusla 2017). Through this experience, they had developed a working knowledge of processes such as scripting and storyboarding (mapping out animated and interactive content on a scene-by-scene basis). However, the technicalities and best practice principles were far beyond the knowledge and scope of competence of the team members.

4. Exploration and Establishment of Solutions to Overcome the Challenges to CFIAS Service Provision Posed by the COVID-19 Pandemic

4.1. Review of PowerPoint and Training Resources

We commenced work by reviewing existing training and briefing packages, looking at both PowerPoint decks and the trainer guidance materials. Team members accessed training on instructional design, eLearning theory and pedagogy, and online facilitation through Tusla’s Work Force Learning and Development (WLD) section, as well as sourcing online tutorials and reviewing other organisations’ offerings.

As we researched and accessed learning opportunities, it quickly became evident that many of our materials were dated (in terms of design principles) and in need of revision. As Schmaltz and Enström (2014, p. 1) note, “Strong PowerPoint presentations enhance student engagement and help students retain information (e.g., Susskind 2005), while weak PowerPoint slides can lead to distraction, boredom, and impeded learning (Savoy et al. 2009)”. As part of the preparation for remote delivery, then, the existing PowerPoint decks were revisited and revised to make them more visually engaging and animated (see Figure 2, below).

Figure 2.

Before and after PowerPoint revision: (a) old slides were 4:3 scale and text heavy; (b) revised slides were 16:9 scale and included graphics, animations, and key words for greater clarity.

Initially, as a quick fix, it was agreed to revise four of our existing, core briefing programmes for remote delivery over MS Teams (Tusla’s preferred online meeting platform).

4.2. Mapping Possible Options to Overcome the Challenges to CFIAS Service Provision and Team Consultation

One of the key challenges within the CFIAS at this time was differing understanding and knowledge of virtual learning, exacerbated by a lack of a shared vocabulary. Shared language and understanding are key to effective collaborative work (Thomas and McDonagh 2013). We set about generating a glossary and agreeing how we would use language based on common parlance in the field at the time. Those leading the change programme also recognised the variety of factors which can inhibit or affect change readiness and resistance to change (Furxhi 2021, p. 23), including “(a) mistrust and lack of confidence; (b) emotional response; (c) fear of failure; (d) poor communication; (e) time”. Consultation, defined language, support and peer mentoring, training, and workshops were all employed to mitigate resistance to change and build readiness.

Within the CFIAS, it was necessary to hear and acknowledge the anxieties expressed by colleagues. Reassurances were required from management on the role of technology in the workplace vis-à-vis the security of posts and work. Agreement was reached that any digital resources being developed during the pandemic had to support the existing work of the CFIAS rather than replace it. It was acknowledged, as well, that digital resources could have a much broader reach. As noted by Tugtekin and Dursun (2022, p. 3248), “Multimedia-rich learning environments not only create a unique learning experience for participants, but also have an impact on their engagement”. Team members were able to acknowledge the benefit that animations and videos could bring to distance learning, and also to support engagement, post pandemic, in in-person learning events.

4.3. Establishing Support Partnerships and Networks

To build knowledge and garner information, team members established a working partnership with Tusla’s WLD, which was also grappling with similar challenges. Through this intra-agency partnership, the CFIAS was able to access a WLD colleague with experience in digital instructional design who provided advice and information on software packages, temporary use of a software licence, and supported access to in-house training. This also facilitated the sharing of resources and supported consistent messaging and branding across the Agency’s internal and external learning environments.

4.4. Review of Possible Tools and Packages to Address the Identified Challenges to CFIAS Service Provision

Building on our engagement with Tusla WLD and the review of a variety of content styles, the CFIAS determined that, for information delivery purposes and micro-learnings, we would need a whiteboard animation software package and a video editing software package, as well as peripherals such as headphones and external microphones for authoring and recording. A review was carried out on good-quality peripherals and appropriate software packages. As this was new ground for not just the CFIAS but for many in Tusla, a business case was required outlining cost/benefit, intended usage, and strategic vision for these resources. Support and funding were subsequently secured from senior management.

5. Software Licence Acquisition and Training and Learning Product Development

Approval was granted, and four licences each were acquired for animation software (Vyond) and video editing software (Filmora version 12.2.9). As already noted, work had initially commenced to update Microsoft PowerPoint resources. As the Vyond and Filmora licences came on stream, the team identified a number of projects for development. However, neither budget nor time provided for extensive formal training in the use of these software packages, and the view of other instructional design professionals was that the best thing to do, initially, was to commence work and access public domain tutorials.

5.1. The Journey Begins—Animation Software and Explainer Videos

The CFIAS initially identified four topics for explainer videos; these are short (<5 min), engaging single-topic or concept videos. Given the on-going public health restrictions, it was agreed that products with the widest potential reach for remote access would be most beneficial and could best mitigate the impact of these restrictions on service delivery.

We started with animation software as this was the least complicated of the two products for which we had acquired licences. The authors, who were two of the licence holders, each took a project to develop. Our previous experience as content experts (advisors to an instructional design team) on a previous eLearning programme, and information and training we had accessed in the interim, gave us an understanding of the process to be followed. We commenced by drafting a script, followed by storyboarding the proposed animations. The scripts were checked with Tusla’s Communications Unit and approved by senior management to verify messaging. We also had to liaise with Tusla’s Head of Corporate Identity to ensure branding and so-called “look and feel” were consistent with Tusla guidelines. This meant using appropriately formatted logos, a specified colour scheme, and specific fonts to support consistent brand identity.

While we had no formal training, we found the interface for the animation software to be relatively intuitive to use. YouTube and company tutorials were invaluable in learning how to set certain types of animations, such as zooms, pan-and-scan, and tracked motion. We were fortunate to have more than one licence holder, as this allowed us to share learning and review each other’s work. Challenges included devising and agreeing consistent openers, sharing animation assets for continuity across products, and providing our own voiceovers. In one instance, to support the topic being covered (child and youth participation), one of the licence holders recruited her own children to record the voiceovers. This proved extremely effective, providing a product that literally supported ‘the voice of the child’, which is a central tenet of the Children First National Guidance (Department of Children and Youth Affairs 2017).

5.2. Heading in a New Direction—Creating Self-Directed eLearning

As animations were completed and additional projects identified, the CFIAS built on its partnership with Tusla WLD to develop a self-directed eLearning module using Articulate 365. A team member was ‘loaned’ a licence and was able to build training for mandated persons (under the Children First Act 2015). The Children First Act 2015, which commenced in December 2017, introduced what are called mandated persons (s. 14). Mandated persons have particular legal responsibilities to report certain concerns and assist Tusla in assessments in specific situations. The categories of persons mandated under Schedule 2 of the Children First Act include all medical professionals, teachers, and many other professionals. There is no estimate of the number of mandated persons in Ireland; however, given the numbers of schools, medical professionals, youth organisations, etc. (see Section 5.3, below), it is likely to be in the tens of thousands, at least. Mandated persons’ training was a priority area identified for which, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was impossible to deliver direct training.

Significant further discussion was required within the CFIAS to address concerns about the position of technology and perceived potential threats to existing roles and responsibilities. Burgess and Connell (2020) note the considerable research which has been conducted on the threats perceived by workers posed by automation and new technologies, as well additional complications posed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the move to so-called technology-based work locations (remote working). These were reflected in our own experience.

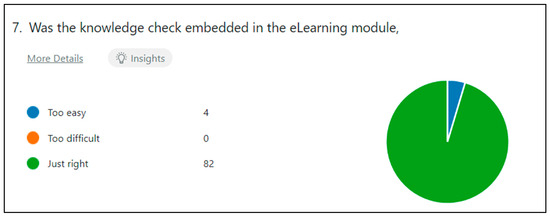

As a service, we have built on our existing knowledge and developed resources which are universally accessible, as they are hosted on the internet. As we grew in confidence with the animation software, we also were able to explore additional uses for the technologies we had access to. The eLearning programme for mandated persons was successful in terms of its reach. It was initially launched on a pilot basis, with an embedded evaluation for review of content and functionality. Feedback was overwhelmingly positive (n = 93 pilot participants). For example, overall rating from those participating in the pilot was 4.7/5, rating for design and layout was 4.71/5, and 95% of pilot participants found the embedded knowledge checks to be “just right” (see Figure 3, below). Constructive comments were used to hone the product for the final version.

Figure 3.

Review of knowledge check in mandated person eLearning module pilot by number of answers.

5.3. Walking the Path—Designated Liaison Person eLearning Development

Following the success of the mandated person eLearning programme, the CFIAS further identified how eLearning and explainer videos could be used for information delivery and to support the lower three domains of Bloom’s taxonomy of learning (McGrae 2019). This led to another business case, for two licences for Articulate 365, a suite of eLearning authoring tools. The benefits and flexibility of self-directed eLearning were recognised within the team, particularly its ability to support learner autonomy, on-going access to information, and learner-led prioritisation (Bonk and Zhu 2023).

An eLearning programme was developed for so-called “designated liaison persons”, or DLPs—those with an identified organisational responsibility for child safeguarding within their organisations under the Children First National Guidance for the Protection and Welfare of Children (Department of Children and Youth Affairs 2017). All organisations in Ireland which provide services to children are recommended to have a DLP in place (Department of Children and Youth Affairs 2017). While the number of organisations within the scope of this recommendation has never been quantified, to provide some context, in Ireland, there are over 3500 schools (primary and post primary) (Department of Education 2022), over 4500 early learning and care services (Pobal 2022), thousands of sporting clubs operated under the auspices of the more than 60 national governing bodies (Sport Ireland 2023), and 55 national youth organisations which run thousands of clubs across the country (NYCI 2022).

One of the digital resources developed to form part of the DLP eLearning was a short webinar, Understanding the Post-Referral Process (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2023b), narrated by the Tusla Chief Social Worker. The webinar integrates face-to-camera narration, voiceovers, animations, and video effects. This webinar also serves as a standalone resource, hosted independently on the Tusla website and YouTube channel.

5.4. Further on Down the Road—Development and Review of the DLP Blended Training Programme

The DLP eLearning was developed to be universally accessible to the thousands of DLPs across Ireland, and also to serve as part of a blended learning programme for DLPs in key stakeholder organisations for which Tusla holds a responsibility. This was in recognition of the limited capacity of self-direct eLearning to explore in-depth concepts, as noted by Atta and Alghamdi (2018, p. 623), who found “[self-directed learning] appears to be less valuable for promotion of self-readiness. Periodic discussions in small groups or by panel discussion are strongly recommended for students to enhance readiness with [self-directed learning]”.

The blended programme is comprised of the 1.5-h DLP eLearning, supported by an additional 3.5-h classroom-based DLP workshop, replacing a one-day classroom-based DLP training programme.

Pilots and Evaluation of the Blended DLP Training Programme

In developing the blended DLP training programme, the CFIAS reviewed agreed training objectives and learning outcomes (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2018). The DLP eLearning module was reviewed, and any gaps identified from the existing DLP learning outcomes were marked for inclusion in the blended learning programme. It was the view of the development team that eLearning was better suited to the communication of information, rather than the higher domains of Bloom’s taxonomy, as reflected by Atta and Alghamdi (2018). The CFIAS piloted a draft DLP workshop on two occasions, followed by a third pilot after final revisions. Each pilot included focus groups of participants, used to generate feedback on both the self-directed eLearning module and the facilitated workshop. The consensus reported by focus group participants was that the eLearning provided flexibility, was appropriately pitched, and delivered information which was both useful and assisted them to participate fully in the facilitated workshop. Focus group participants noted the benefit of a facilitated workshop to provide an opportunity to explore in more detail the nuances and complexities of the DLP role.

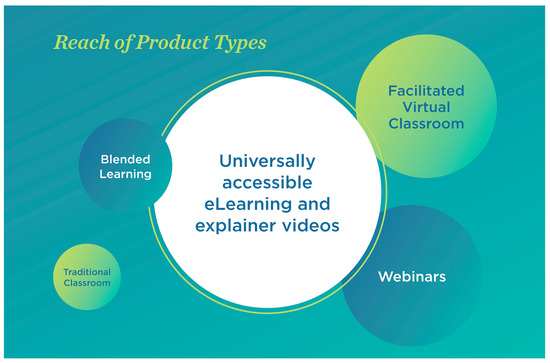

6. On-Going Use of CFIAS Training and Learning Products

The CFIAS has now developed a suite of resources (see Appendix A: Electronic Resources Developed by the CFIAS) which have multiple uses, are relevant to a wide target audience, and have significantly wider reach than previous face-to-face offerings (see Figure 4, below).

Figure 4.

Reach of product types.

These include:

- The aforementioned revised PowerPoint presentations for delivery in a virtual learning environment (which are also suitable for face-to-face delivery). These resources support remote delivery to teams located in disparate geographic locations or where training venues are not readily available;

- A number of explainer videos and micro-learnings. These are used as standalone products, hosted on the Tusla website and YouTube channel, which are universally accessible. Some are also embedded in self-directed eLearning and/or facilitated training programmes supporting multimedia presentation, variety of content, and a guarantee of consistent information delivery;

- Self-directed eLearning modules which allow particular cohorts of professionals who have specific child safeguarding responsibilities to access information at a time and place of their own choosing. The self-directed eLearning modules have knowledge checks embedded and generate certificates of completion (Mandated Person eLearning), which support the continuing professional development needs of many Irish professionals affected by child safeguarding legislation and policy;

- Blended learning which utilises both self-directed eLearning and facilitated workshops. The self-directed learning component is used primarily for information delivery and to introduce concepts and terminology. This supports better use of the facilitated time to explore values, understanding, and implementation of learning concepts (i.e., the higher domains of Bloom’s taxonomy (McGrae 2019)).

At the time of writing, there are a number of additional resources in development. It is the authors’ view that the catalyst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and associated public health restrictions, precipitated a drive towards new and varied training and learning products and methodologies.

7. Effect of Training and Learning Tools and Products and Next Steps: Into the Great Wide Open

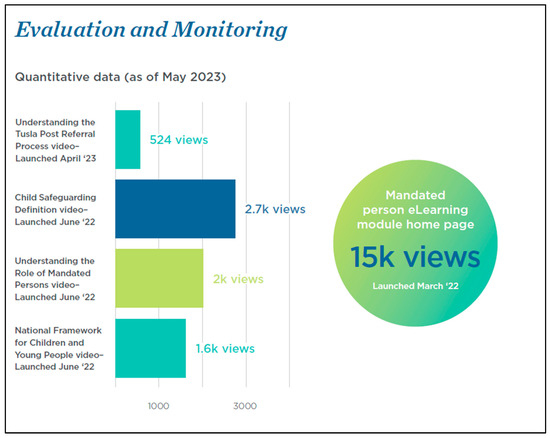

7.1. Quantitative Data—Reach of the Explainer Videos and eLearning Programmes

As of May 2023 (see Figure 5, below), the explainer videos have been accessed approximately 7000 times (three of these have been available for less than 11 months, the fourth for one month). The eLearning programmes have been visited over 40,000 times, to August 2023 (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2023c) (one went live in March 2022, the other in June 2023). Previously, information would have been delivered through face-to-face briefings and training programmes with a maximum reach of approximately 2000 people per annum.

Figure 5.

Quantitative data by programme, to May 2023.

7.2. Qualitative Data—The Views of Product Users

Following the introduction of the revised PowerPoint, explainer videos, self-directed eLearning, and blended learning, there is overwhelming consensus from members of the CFIAS on the benefits brought by the new product offerings, as reported through informal feedback and professional conversations.

Similarly, service user feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. Three pilot programmes were run for the DLP blended training with 51 people attending. Following each pilot, three focus groups were held with participants (nine focus groups in total). Across all focus groups, recorded views were mainly positive. However, there were one to two people from each participant group who provided slightly critical views on duration, content, and usefulness of the facilitated and self-directed eLearning components. Comments included:

“It was good to recap some points from the eLearning in face-to-face training”;

“There are so many changes, like mandated reporting, that face-to-face training gave clearer guidance”.

Focus group participants also commented on the DLP eLearning. Individuals liked the diversity of presentation methods used, reported that the language in the programme was accessible and that knowledge checks tested their knowledge appropriately, and liked that there were links to additional resources. There was a useful suggestion to include subtitling, which has been incorporated, among other things. Overwhelming agreement was reported by participants in the focus groups that completion of the self-directed eLearning module greatly enhanced their preparation for the in-person workshop.

The CFIAS has also received anecdotal feedback from staff and managers in partner organisations which listed accessibility, clarity, and flexibility as benefits found in the self-directed resources produced, such as explainer videos, webinars, and eLearning modules.

7.3. Learning and Reccomendations

Based on our experience over the past three years, we have gleaned a number of insights. The authors recognise that there are limitations to the support for these learnings given that this project report is based on a review of lived experience within a service rather than structured research. The findings, listed below, are based on analysis of limited qualitative and quantitative data, as well as the experiential learning of the CFIAS in responding to the challenges arising during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The availability of freely available tutorials and information supports novice designers to build skills and techniques. Formal training in instructional design should be offset with self-directed learning and self-guided practice and design development;

- Use it or lose it—our licence holders have all reported that if they are not using the software regularly, there is often a delay when they re-engage, caused by having to re-orient and re-learn techniques;

- Resistance to change is normal, as is the sense of threat that new work processes can bring. Dialogue, consideration, and testing solutions before wholesale adoption mitigate resistance and alleviate the sense of threat;

- Capacity building within a service builds autonomy and long-term benefits. In accessing software licences and support to build capacity, the CFIAS has developed skills which allow us to more quickly and efficiently build products which reach a far wider audience than previously possible. This brings a net savings to Tusla as in-house design and build replaces the need for expensive contracted instructional design consultants. This also allows in-house licence holders freedom to make changes and updates to materials;

- The value of widely accessible information and training provision, which can be individually matched to learners’ needs, was reflected in participants’ feedback. This includes self-directed and facilitated learnings, as appropriate to different individuals’ and organisations’ specific needs;

- Developing products which can be utilised in multiple settings increases cost effectiveness and supports consistent messaging. In developing revised PowerPoint decks and new explainer videos, we built greater efficiencies by ensuring products were suitable for stand-alone use, as well as capable of being integrated into other learning or information programmes.

In addition to the learning listed above, it is the recommendation of the authors that research should be conducted to explore whether there has been a sustained change to modalities of child safeguarding information and training delivery as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Learning could be garnered from a cross-jurisdictional study.

We are also of the view that further study on the efficacy of various models of information and training delivery on values-related topics (such as child safeguarding) would be beneficial.

7.4. Conclusions

The CFIAS is comprised of a team of 11 Children First Information and Advice Officers, based in locations across Ireland (population ~5 million (CSO 2023)). The adoption of technological solutions to support the CFIAS work through information provision, distance learning, online facilitated learning, self-directed learning, and blended learning has exponentially increased the capacity of a small staff team to reach a larger audience.

There were inherent challenges in moving from solely classroom-based learning and face-to-face meetings to deliver information and support understanding of child safeguarding responsibilities. These included lack of technical expertise, resistance to change, concerns about the impact of technology on existing roles and functions, and uncertainty about the efficacy of technological solutions to deliver desired outcomes. Dialogue within the team, research, and lived examples were used to overcome these challenges and support buy-in and cooperation in the move to a broader range of resources, which included technological solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W.; methodology, C.W. and J.P.; validation, C.W. and J.P.; formal analysis, C.W.; investigation, C.W.; resources, C.W. and J.P.; data curation, C.W. and J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.W.; writing—review and editing, C.W. and J.P.; visualization, C.W.; project administration, C.W. and J.P.; funding acquisition, C.W. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by Tusla—Child and Family Agency.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was secured from focus group participants. The focus group was a review of a pilot training programme, and formed part of the training programme development process, rather than a piece of research.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not publicly available. The data is drawn from organisational use of web cookies, analysis of anonymous electronic learner evaluation forms from the pilot phase of an eLearning programme, and notes from focus groups conducted as part of pilot training evaluation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Boyd Dodds, Tusla Area Manager Children First and Garda Liaison; Colette McLoughlin, Tusla Service Director, National Office Services & Integration; and Ger Brophy, Tusla Chief Social Worker, for their support in putting this project forward.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Electronic Resources Developed by the CFIAS

eLearning programmes:

- Tusla ‘Children First Mandated Person Roles and Responsibilities eLearning’: https://www.tusla.ie/children-first/mandated-persons/ (accessed on 11 September 2023);

- Tusla ‘Designated Liaison Person eLearning’: https://www.tusla.ie/children-first/organisations/appointing-a-designated-liaison-person/ (accessed on 11 September 2023).

Explainer videos:

- Child Safeguarding Definition: https://www.tusla.ie/children-first/organisations/ (accessed on 11 September 2023);

- National Framework for Children and Young People’s Participation: https://www.tusla.ie/services/family-community-support/tusla-child-and-youth-participation/national-framework-for-children-and-young-peoples-participation/ (accessed on 11 September 2023);

- Understanding the Post-Referral Process: https://www.tusla.ie/children-first/parents-and-guardians/what-happens-after-i-make-a-report-to-tusla/ (accessed on 11 September 2023);

- Understanding the Role of Mandated Persons: https://www.tusla.ie/children-first/mandated-persons/#:~:text=Mandated%20persons%20are%20people%20who,help%20protect%20children%20from%20harm (accessed on 11 September 2023).

Notes

| 1 | Report of the Kilkenny Incest Investigation (McGuinness 1993), Report on the Inquiry into the Operation of Madonna House (Department of Health 1996); Kelly—A Child is Dead, Interim Report of the Joint Committee on the Family (Western Health Board 1996); Report of the Independent Inquiry into Matters Relating to Child Sexual Abuse in Swimming (Murphy 1998); West of Ireland Farmer Case: Report of the Review Panel (North Western Health Board 1998). |

| 2 | The learning outcomes for level 1 are outlined in the Tusla Best Practice Principles for Organisations in Developing Children First Training (Tusla—Child and Family Agency 2017). The Tusla ‘An Introduction to Children First’ eLearning programme meets the requirements for Level 1. |

References

- Atta, Ihab Shafek, and Ali Hendi Alghamdi. 2018. The efficacy of self-directed learning versus problem-based learning for teaching and learning ophthalmology: A comparative study. Advances in Medical Education and Practice 9: 623–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonk, Curtis J., and Meina Zhu. 2023. On the Trail of Self-Directed Online Learners. ECNU Review of Education, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, Helen. 1998. Conflicting Paradigms: General Practitioners and the Child Protection System. Irish Journal of Social Work Research 1: 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, Helen. 2000. Inter-agency Co-operation in Irish Child Protection Work. Journal of Child Centred Practice 6: 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, John, and Julia Connell. 2020. New technology and work: Exploring the challenges. Economic and Labour Relations Review 31: 310–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Rory. 2020. ‘Stay home’: Varadkar Announces Sweeping Two-Week Lockdown. The Irish Times. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/27/stay-home-varadkar-urges-irish-in-drastic-lockdown (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Children First Act 2015 (no. 36). Dublin: Government Publications.

- CSO. 2023. Population and Migration Estimates, April 2023. Available online: https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-pme/populationandmigrationestimatesapril2023/keyfindings/ (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Department of Children and Youth Affairs. 2017. National Guidance for the Protection and Welfare of Children; Dublin: Stationary Office.

- Department of Education. 2022. Statistical Bulletin—July 2022: Overview of Education 2001–2021. Available online: https://assets.gov.ie/212277/407f0406-1704-421b-ab9e-469562df5753.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Department of Health. 1996. Report on the Inquiry into the Operation of Madonna House; Dublin: Government Publications.

- Department of Health and Children. 1999. Children First—National Guidelines for the Protection and Welfare of Children; Dublin: Stationary Office.

- Furxhi, Gentisa. 2021. Employee’s Resistance and Organizational Change Factors. European Journal of Business and Management Research 6: 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan-Jones, Jack, Cormac McQuinn, and Vivienne Clarke. 2022. ‘Time to Be Ourselves Again’: Taoiseach Confirms end to Almost all COVID-19 Restrictions—The Irish Times. Irish Times. January 21. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/time-to-be-ourselves-again-taoiseach-confirms-end-to-almost-all-covid-19-restrictions-1.4782227 (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- HSE and Tusla. 2017. An Introduction to Children First (eLearning Programme). Available online: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/2/primarycare/childrenfirst/training/ (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- Kelly, John. 1997. What Do Teachers Do With Child Protection and Child Welfare Concerns Which They Encounter in Their Classrooms? Irish Journal of Social Work Research 1: 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- McGrae, Ben. 2019. A spotlight on... Learning Outcomes with Bloom’s Verb Guide Centre for Innovation in Education. Available online: https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/centre-for-innovation-in-education/staff-guides/learning-outcomes-with-blooms-verb-guide/learning-outcomes-with-blooms-verb-guide.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- McGuinness, Catherine. 1993. Report of the Kilkenny Incest Investigation; Dublin: Government Publications.

- Murphy, Roderick. 1998. Report of the Independent Inquiry into Matters Relating to Child Sexual Abuse in Swimming; Dublin: Government Publications.

- North Western Health Board. 1998. West of Ireland Farmer Case: Report of the Review Panel. Dublin: North Western Health Board. [Google Scholar]

- NYCI. 2022. Annual Review 2021. Available online: https://www.youth.ie/documents/nyci-annual-review-2021/ (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Pobal. 2022. Early Years Sector Profile Annual Report 2020/2021. Available online: https://www.pobal.ie/app/uploads/2022/05/Pobal_22_EY_20-21-Report_final_2.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Reder, Peter, Sylvia Duncan, and Moira Gray. 1993. Beyond Blame: Child Abuse Tragedies Revisited. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Savoy, April, Robert W. Proctor, and Gavriel Salvendy. 2009. Information retention from PowerPoint™ and traditional lectures. Computers & Education 52: 858–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schmaltz, Rodney M., and Rickard Enström. 2014. Death to weak PowerPoint: Strategies to create effective visual presentations. Frontiers in Psychology 5: 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sport Ireland. 2023. NGB Overview. Available online: https://www.sportireland.ie/national-governing-bodies/ngb-overview (accessed on 6 October 2023).

- Susskind, Joshua E. 2005. PowerPoint’s power in the classroom: Enhancing students’ self-efficacy and attitudes. Computers & Education 45: 203–15. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Joyce, and Deana McDonagh. 2013. Shared language: Towards more effective communication. The Australasian Medical Journal 6: 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugtekin, Esra Barut, and Ozcan Ozgur Dursun. 2022. Effect of animated and interactive video variations on learners’ motivation in distance Education. Education and Information Technologies 27: 3247–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tusla—Child and Family Agency. 2016. Child Safeguarding Training Standards and Learning Outcomes, Unpublished.

- Tusla—Child and Family Agency. 2017. Best Practice Principles for Organisations in Developing Children First Training Programmes; Dublin: Government Publications.

- Tusla—Child and Family Agency. 2018. Child Safeguarding Training Standards and Learning Outcomes—Updated, Unpublished.

- Tusla—Child and Family Agency. 2021. Tusla Corporate Plan 2021–2023. Available online: https://www.tusla.ie/corporateplan21-23/ (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Tusla—Child and Family Agency. 2023a. Tusla–Child and Family Agency About Us Page. Available online: https://www.tusla.ie/about/ (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Tusla—Child and Family Agency. 2023b. Understanding the Post-Referral Process. Available online: https://www.tusla.ie/children-first/individuals-working-with-children-and-young-people/how-do-i-report-a-concern-about-a-child/#:~:text=It%20is%20Tusla’s%20role%20to,where%20sufficient%20risk%20is%20identified (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Tusla—Child and Family Agency. 2023c. Web Use Metrics, Unpublished.

- Vradkar, Leo. 2020. Statement by An Taoiseach Leo Varadkar On measures to tackle COVID-19 Washington, 12 March 2020. Merrion Street. Available online: https://merrionstreet.ie/en/news-room/news/statement_by_an_taoiseach_leo_varadkar_on_measures_to_tackle_covid-19_washington_12_march_2020.html (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Western Health Board. 1996. Kelly—A Child is Dead, Interim Report of the Joint Committee on the Family; Dublin: Government Publications.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).