Abstract

Migration processes entail a change in the conditions of the existence of its protagonists as they integrate into a new life, where work is of paramount importance. For this reason, it is interesting to know the working conditions of immigrants when they settle in the new host country, as it is up to the latter to design policies that strengthen their integration, with decent work being relevant, as it has an impact on the well-being of these people, as set out in the great challenge of the Global Compact. Thus, a study was conducted on the working conditions of Venezuelan immigrants settled in the border cities of Cúcuta, Los Patios, and La Parada (Colombia) using a quantitative methodology through a multidimensional analysis of the factors related to their occupation, projecting a perceptual map with similarities and differences that show the characteristics of their current working conditions. These findings made it possible to determine that the current working conditions do not correspond to decent work, which requires the design of proposals by those who manage the governance of migration that favour labour insertion and the achievement of the sustainable development objective of decent work.

1. Introduction

The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development presents several important challenges in the quest for sustainable development. As per the sustainable development goals (SDGs), Goal 8—decent work and economic growth—seeks to promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment, and decent work for all who face the poverty, inequality, and unemployment that burden the world; hence, approximately 500 million jobs need to be created between 2016 and 2030, such that, as people enter the labour market, the regularity of the growth of the world’s working-age population is maintained (United Nations 2015b). Decent work implies that people engage in a productive activity that earns a reasonable income and provides security in the workplace, social protection for the family, facilities for personal development, gender equality in opportunities in the workplace, and social integration, such that there is a common benefit towards the progress and growth of the country (United Nations 2015a). Thus, a scenario of humanization in development is proposed and the dignity of the working human being becomes the key foundation for the achievement of objective 8; human dignity cannot be isolated from development, the dignity of the worker and their respect and realization as a human being, as a subject of rights (Martínez 2013).

Together with the challenge of sustainable development, the phenomenon of international migration has increased in recent years. Migrants move to new destinations seeking to improve their living conditions and well-being, so they require employment that provides them with income (Agudelo 2019). Therefore, Goal 8, decent work and economic growth, which seeks to protect labour rights and motivate safe and risk-free work scenarios for all workers, including immigrants, especially women and those in unstable employment, becomes important (United Nations 2015b).

Studies such as those by Peñafiel and Rea (2022), Bravo (2022), and Camas (2021), addressed migration with the labour status of migrants and the challenge of decent work in the 2030 Agenda. Peñafiel and Rea (2022) determined the compliance of Venezuelan migrants with their labour rights in the business sector in Riobamba based on what is expressed in international instruments and Ecuadorian legislation. In conclusion, it was found that the labour rights of immigrants are violated, the right to social security represents one of the most recurrent problems for immigrant workers, they do not have affiliation with the Ecuadorian Institute of Social Security, salaries are not adequate in most cases due to their irregular migratory situation, and they do not enjoy labour stability and therefore do not last long in their jobs; hence, they cannot protect themselves from contingencies that may arise.

In his work, Bravo (2022) sought to understand the effects in Ecuador of the informal work of undocumented Venezuelan immigrants; however, the analysis reveals the violation of principles and rights in the labour contractual relationship of immigrants when situations arise such as a lack of registration in the Single Labour System (SUT), no affiliation with the Ecuadorian Institute of Social Security, and no remuneration in accordance with the law and legal benefits. By working in the informal sector, Venezuelan immigrant workers do not enjoy the rights established by law and cannot access the justice system to fight for them because they do not have the necessary resources in addition to being in an irregular migrant situation.

The study by Camas (2021) raises, in legal and social terms, the situation of foreign domestic workers in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus pandemic and its health and economic emergencies. It presents proposals to make the principle of decent work effective, incorporated as a Sustainable Development Goal in the United Nations 2030 Agenda, in addition to studying measures that would improve the working conditions of migrant domestic service workers in Spain, a country where the substitution of native women in domestic work has been occurring progressively, caused by the low valuation of this type of work, whose characteristics include being heavy, dangerous, precarious, poorly paid, and socially penalized, which leads to poor working conditions conducive to informal employment. It raises discrimination against migrant women workers in domestic service, a factor that prevents the achievement of decent work, whose objectives include the adoption and extension of social protection measures, such as social security and the recognition of safe and healthy working conditions, including an adequate salary; in addition, promoting social dialogue as a rule to apply it to the other objectives respects, activates, and uses the fundamental principles and rights at work.

However, studies indicate that migrants encounter obstacles to decent work and thus to labour and social integration in the host country, so migration and labour integration policies in the receiving country, from the perspective of migrant composition (Guzi et al. 2023), are important to ensure the fulfilment of Goal 8 of the 2030 Agenda, decent work and economic growth.

One of the migration scenarios of recent years is the flow of migrants who have left Venezuela for ideological, political, economic, and social reasons due to the crisis that the South American country is experiencing (Cerruti 2020; Mazuera-Arias et al. 2020). This pushes them to migrate to countries where they can cover their basic needs, send money to their families, and improve the living conditions of themselves and their families (Camarero 2010; Castilla-Vázquez 2017; Laajimi and Le Gallo 2022). Among this wave of migrations are young professionals of working age who are motivated to migrate because of poor future prospects for personal growth, precarious wages, poor working conditions, low growth opportunities within organizations, company closures, and underemployment, unemployment, or informal employment with no social or labour guarantees (David and Joachim 2016; Dibeh et al. 2018; Milasi 2020; Zisi et al. 2022).

In Latin America and the Caribbean, by August 2023, there were approximately 6.52 million Venezuelan immigrants and refugees—2.9 million in Colombia, 1.5 million in Peru, 477.5 in Brazil, 474.4 in Ecuador, and 444.4 in Chile (Interagency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela 2023). How do decent work and respect for decent working conditions manifest themselves among Venezuelan immigrants? In search of an answer, a study was conducted in the border areas between Venezuela and Colombia, specifically in the Department of Norte de Santander, which has an approximate Venezuelan population of 260,369 people (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs 2023) considering Cúcuta, Los Patios, and La Parada, cities where immigrants, following the definition of this term according to the International Organization for Migration (2019), have settled and worked for six months or more. These cities are part of the so-called Metropolitan Area of Cúcuta, a space that ensures a political, administrative, and fiscal regime used to manage the fulfilment of its functions, within the autonomy recognized by the Political Constitution and the law (Congress of the Republic of Colombia 2013).

The population of the metropolitan area of Cúcuta is 1,046,347 inhabitants (Together We Can Foundation 2023); the last updated figure on the distribution of Venezuelans in Colombia in February 2022 from Migration Colombia (2022) showed the presence of 167,678 Venezuelans in this area, although the website The Venezuelan (2023), for April, states the presence of approximately 218,000 between Venezuelan immigrants and returnees.

Therefore, this study found the characteristics of the current labour conditions of Venezuelan immigrants in these cities based on a quantitative methodology. Utilizing a multidimensional analysis of the factors related to the occupation of Venezuelan immigrants, the study obtained a structure of associations between the group of categorical variables, as well as the similarities and differences in working conditions, which were projected onto a two-dimensional plane or perceptual map. This provides evidence about the state of the conditions required for decent work, which could aid proposals that facilitate the lives of immigrants in a way that strengthens their human dignity (Cely 2009). The findings can be used as a starting point by entities responsible for overseeing compliance with the rights of working immigrants in accordance with the standards of the International Labour Organization and United Nations (International Labour Office 2004) and those who oversee the implementation and enforcement of migration policies to design or redesign actions that take advantage of the opportunity that migration represents, minimize events that complicate the lives and quality of life of those involved in the study, or strengthen social cohesion and the identity of the immigrant as a human being and citizen.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Work Conceptualization

Work, as a human activity, involves the use of intellectual and motor skills and the individuality of workers (Fernández and Paravic 2003), who feel satisfaction when contributing to the achievement of the goals of the organization to which they belong and, therefore, to the development of the society; hence, work influences most aspects of human behaviour (Robbins and Judge 2009). These activities may or may not be remunerated in terms of employment when there is payment through a salary, wage, commission, tip, or in kind, without considering the relationship that may exist between the payer and the worker. The latter may be dependent on the former, as an employee with or without a contract of employment, or they may be independent; that is, their own employer (Levaggi 2004).

Therefore, there may be a legal bond between employers and workers that determines their relationship, which occurs if a person provides work, under certain conditions, in exchange for compensation (International Labour Organization n.d.). Although the current social reality of a changing and fluid globalized world that is in constant flux has generated specific diversifications for work, to the extent that the concept of the employment contract is not reflected in reality, today we reflect on protection for all types of work, not only those that are subordinate or dependent. Thus, the legal qualification of specific situations of work and employment may be proposed through the definitions of occupational categories where the presence or the lack of an employment contract, employee, employer, and personal provisions of a service are defined (Maldonado n.d.; Canales 2012).

In this way, currently, the concept of decent work means good or dignified work (Levaggi 2004) because, according to the International Labour Organization (2007), a decent job provides opportunities for productivity, fair income, security in the workplace, and social protection for the worker and their family, creating opportunities for personal development and promoting social integration, which offers employees the freedom to express themselves, mobilize with each other, and participate in decision making on issues that affect their lives, in addition to providing guarantees of equality for all in terms of opportunities and treatment.

2.2. Worker in a Dependent Employment Relationship

Dependent work is that which exists when a person provides their services to another person who facilitates work opportunities in exchange for payment; this relationship is characterized by being unequal and subordinate, as the worker is subordinated by agreeing to carry out the work under the methodology established by the employer, with a salary that is their main source of income for their subsistence and that of their family; furthermore, the employer has the power to give them orders to lead them to achieve the company’s own objectives. On the other hand, it is unequal, since the worker, due to his technical, economic, and legal subordination, is in an inferior position with respect to the employer. Thus, if there is no subordination, the person providing a service would be acting independently (Echegaray 2019). In the case of immigrants, dependent work can lead to abusive conditions on the part of the employer, such as lower wages and precarious conditions in jobs that are less desirable for national residents in the context of market segmentation, even more so if the immigrant is in a situation of illegality in the host country (Castles and Miller 2004); for example, when the employer offers the irregular immigrant a job to work informally without social security affiliation.

2.3. Entrepreneurs

An entrepreneur is a person who takes risks, innovates, identifies, and creates business opportunities individually or collectively; they seek some benefit, have interests and dreams to obtain a different way of life, or are unable to obtain a traditional job. The entrepreneur decides whether or not to create a formal company, becoming its owner motivated by a sense of achievement (Albornoz-Arias and Santafé-Rojas 2022; Bergner et al. 2021; Bruneau and Machado 2006; cited in Kantis et al. 2004; McClelland 1989; Rogoff 2007). Thus, the entrepreneur is a person who works independently and can provide a service or a product, which is linked to their business model; they work autonomously, offering knowledge and a labour force in exchange for remuneration (Canales 2012).

Specifically, from the immigrant’s point of view, entrepreneurship represents a way to improve their situation and quality of life and becomes a path for the individual to achieve independence in their work through a process of perseverance. Thus, self-employment can be considered the simplest form of entrepreneurship (Vallmitjana 2014). However, the labour situation of the immigrant, from this business perspective, may fall into the informal economy, either due to illegal or irregular migration or due to the high supply of workers (Castles and Miller 2004). When informality occurs in Colombia, according to Rubio (2014), the worker lacks a specific legal basis that establishes his rights and provides a sanction for anyone who affects an informal worker; thus, in the case of immigrants, access to the goods and services necessary to have a dignified life is difficult, and they may not be covered by public social security systems, as is the case with street vendors or home-based workers (Samaniego-Erazo et al. 2020).

2.4. Work Conditions in Decent Work

The Inter-American Development Bank (2017) states that, qualitatively, labour conditions refer to the primary characteristics of people’s jobs related to formal employment and work in exchange for sufficient pay. Formal employment involves access to social security benefits, which is not the case with informal employment, impacting social welfare. Work with a sufficient salary is equivalent to USD 2.15 per hour, based on the analysis of the standard of living (Ferreira et al. 2015) and the adjustment of the World Bank’s poverty line (World Bank 2022).

Therefore, in order to study the working conditions of immigrants from the perspective of decent work, it is necessary to know certain socio-demographic and migratory conditions, together with others specific to the labour sphere in which they work, such as how the job was obtained, the sector to which it corresponds, the productive sector, the job or position held, whether or not a contract is signed, the benefits received, the existence of situations of discrimination or not in accordance with labour laws, and the salary or wage received. Thus, this study considers employees to be those who work in the public or private sector, and entrepreneurs to be those who work as employers, self-employed, or in informal jobs and aims to understand their working conditions considering the composition of immigrant workers.

3. Colombia Context

The Colombian population is approximately 52 million (National Administrative Department of Statistics 2023), which includes almost three million Venezuelans according to the Interagency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (2023). One of the problems that Colombia faces in the labour sphere is informality, with a rate of over 60% of total employment, which is why the social and solidarity economy is promoted, accounting for 4% of Colombia’s Gross Domestic Product, with 13% of its population affiliated with organizations that are linked to this type of economy (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2022). In the case of the city of Cúcuta, according to the Cúcuta Chamber of Commerce (2023), the informality rate is 57.7%.

In the face of Venezuelan migration, Colombia has managed actions so that immigrants and refugees can integrate, seeking to turn migration into an opportunity for the development and growth of the region (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia 2022). Thus, the National Apprenticeship Service is responsible for recognizing work experience, offering training with complementary training programmes to the regular and irregular population if the latter present a valid document for registration, legitimizing the learning and skills achieved by regular and returned Venezuelan migrants and setting up awareness-raising, counselling, and training sessions aimed at entrepreneurship for this population (Bitar 2022).

For its part, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia (2021) introduced the Temporary Statute of Protection for Venezuelan migrants for 10 years and the Single Registry of Venezuelan Migrants (RMUV), which provides access to work legally, to the Beneficiary Selection System for social programmes and to social assistance programmes. In addition, Law 2136 (Congress of the Republic of Colombia 2021) created a strategy for the integration of the Venezuelan migrant population as a factor of development for the country, CONPES 4100 (National Council for Economic and Social Policy 2022), which contains actions to integrate the migrant population and strengthen the institutional framework commissioned for the governance of care and the integration of migrants.

Other programmes implemented are the School Feeding Programme of the Ministry of Education, Families in Action, Social Protection for the Elderly and Youth in Action, the Solidarity Income of the Colombian Government, and the Single Registry of Foreign Workers in Colombia (RUTEC) (Ministry of Labour 2018), which emerged from CONPES 3950 (National Council for Economic and Social Policy 2018). Also, the Ministry of Labour outlined measures to raise awareness among employers and Venezuelan migrants regarding labour rights and their formal hiring for work. Dissemination campaigns were organized on the services and care routes for migrants, and the Public Employment Service is responsible for providing guidance on access to the employability route (Bitar 2022).

4. Labour Indicators for Cúcuta, La Parada and Los Patios versus Colombia

As labour indicators, between December 2022 and February 2023, the Metropolitan Area of Cúcuta had a 62.9% overall participation rate, 53.9% employment rate, 14.4% unemployment rate and 7.0% underemployment rate; for April–June 2023, the overall participation rate was 60.7%, the employment rate was 54.4%, the unemployment rate was 12.4%, and the underemployment rate was 6.7% (Ministry of Labour 2023), while nationally for December 2022 to February 2023, the overall participation rate was 63.7%, employment 56.2%, unemployment 11.8%, and underemployment 7.9%. For April–June 2023, the overall participation rate was 64.3%, the employment rate was 57.7%, unemployment was 10.2%, and under-occupation was 8.1% (Ministry of Labour 2023).

The data presented indicate that, in the Metropolitan Area of Cúcuta, the proportion of the working-age population participating in the labour market or overall participation rate from December 2022 to June 2023 has been below the national value, from which it can be inferred that, nationally, there is more pressure from the labour force on the labour market (labour supply). Furthermore, for the same period, the percentage ratio between the employed population in the labour market and the number of people of working age or employment rate is lower for the Metropolitan Area of Cúcuta, i.e., the relative size of the demand for labour over the working age population is smaller. On the other hand, unemployment or the percentage ratio between the number of people looking for a job in the labour market and the number of people in the labour force is higher in the Metropolitan Area of Cúcuta, and the percentage ratio between the underemployed population in the labour market and the number of people in the labour force or underemployment is lower in the Cúcuta Metropolitan Area compared to the national value, which indicates that there are more mismatches at the national level between labour supply and demand, reflecting the underutilization of the labour force due to insufficient hours worked.

The above poses a labour scenario for Venezuelan immigrants that hinders their insertion into the labour market, as there is more unemployment than in other cities in Colombia. As a result, they have to adopt an informal approach, either through self-employment or by accepting jobs that do not include contracts, social security, or decent salaries.

5. Materials and Methods

The study applied a quantitative, exploratory, and descriptive approach (Hernández et al. 2010). The data were collected from the study on the experience of Venezuelan immigrants in the border cities of Cúcuta, Los Patios, and La Parada, conducted between July 26 and 16 October 2022. A questionnaire created in Google Forms was used to collect the data and was applied by interviewers through a cell phone or tablet with access to internet data services such that the information was received at the time the questionnaire was applied. A total of 177 immigrants were surveyed as a result of non-probabilistic snowball sampling, with the following inclusion criteria: Venezuelan immigrant over 18 years of age, with regular or irregular migratory status and with more than 6 months of permanent residence in the corresponding city; this study considered 55 people who declared to be working at the time of the survey. For the treatment of the initially obtained data, an exploratory analysis for data validation and a descriptive analysis of the variables under study were conducted.

To determine the joint interdependence relationships between the variables and given their categorical nature, multivariate categorical principal component analysis was used using techniques based on categorical principal components analysis optimal scaling. The reliability of the analysis was measured by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Multiple correspondence analyses quantify categorical data by assigning numerical values to cases and categories, such that cases in the same category are close to each other and cases in different categories are far from each other. Thus, categories divide cases into homogeneous subgroups (Pérez 2004; Meulman and Heiser 2010).

As a result, the structure of associations between the group of categorical variables is described, as well as the similarities and differences projected onto a two-dimensional plane or perceptual map. The statistical procedure was carried out using the multiple correspondence modules by Leiden SPSS Group in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS ver. 24 for Windows).

6. Data

Study Variables

Table 1 shows the distribution of the variable occupational category (understood from the theoretical framework as entrepreneur or employment relationship) according to the demographic variables (age, gender, educational level, and occupational profile) and contextual variables that involve migratory circumstances (current migratory status, immigration document) and work (how the job was obtained, sector of work, productive sector, position held, signed contract, types of benefit, whether the worker found themselves in situations (situations), and salary earned in the last 30 days (salary earned)).

Table 1.

Distribution of immigrants by occupational category.

From the total population under study (n = 55), 8 of 10 working immigrants reported being entrepreneurs, while 2 of 10 immigrants reported being in an employment relationship.

7. Results

The statistical process carried out on the data in Table 1 led to the summary estimate of the multiple correspondence analysis model presented in Table 2. The total variability percentage or total explained variance was 56.11%, with dimension 1 variables contributing 34.73% and dimension 2 contributing 21.38%. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for both dimensions averaged 80.3%, indicating the reliability of the model application.

Table 2.

Model summary.

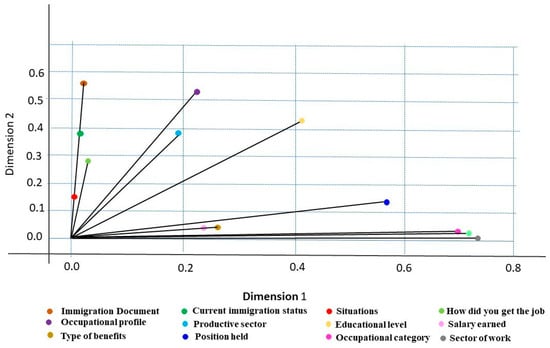

As shown in Figure 1, in the saturation of dimension 1, the variables that discriminate the most and are related are educational level, occupational profile, current migratory status, migratory document, and productive sector, and the variables that discriminate to a lesser extent are “How did you get the job?” and “Have you found yourself in employment situations?” (Situations). In dimension 2, the most discriminating and related variables are position held, occupational category, sector of work, signed employment contract (Signed contract), and, to a lesser extent, types of benefit and salary earned in the last 30 days (Salary earned).

Figure 1.

Discriminant measures. Source: Author’s data.

Figure 1 presents the relationships between the variables on a two-dimensional plane, shown by the discriminant measurements; the orientation and length of the vectors indicate the saturation in the dimensions and the length of the vector shows the importance of the variable. Variables that form an angle < 45° are related.

Looking at Figure 1, there is a relationship between migratory conditions immigration document and current immigration status with situations attached to labour laws but not with signed contract, occupational category, and sector of work; although, among the latter, there is some relationship between them and salary earned, types of benefit, and position held, which, in turn, are related to the educational level, and this to the occupational profile, in terms of the socio-demographic variables.

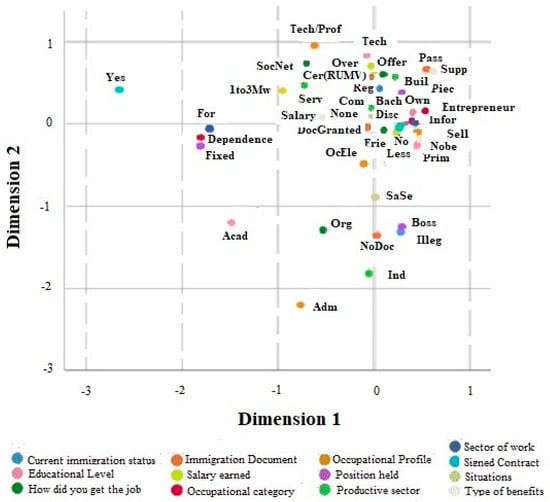

Figure 2 presents the normalization of the main variables, showing the quantification of the categories of variables represented by the coordinates of the vectors in a two-dimensional plane. The interpretation of the centroids of each category allows the analysis of possible associations or patterns of relationships between the categories of variables.

Figure 2.

Set of category dots on a two-dimensional plane. Source: Author’s data. Note: The dots on the plane are the categories for the categorical variables considered. (The abbreviations are detailed in Table 1). It shows a set of coloured dots that represent the categories of variables presented in the text of the figure and that allow it to be interpreted, taking into consideration the proximity of the dots with the dots corresponding to the occupational categories: entrepreneurship and employment relationship.

Thus, Figure 2 structures the characteristics of workers in each category considered in the study. With respect to the issue regarding the occupational category of entrepreneurship, the work sector corresponds to informal employment (Infor), (it can be observed that the dot corresponding to formal employment is further from the entrepreneurship category, meaning that there are some cases, but these are not significant when compared to informal employment). Furthermore, the relationships shown are as follows: On a piece-rate or job basis (Piec) or own account (Own), which are associated with position held; “Less than minimum wage” (Less) linked to salary earned; “No benefit” (Nobe) or “Salary” related to the types of benefit; “Bachelor’s degree” (Bach) and “Primary school” (Prim) associated with educational level; “Commercial” (Com) and “Services” (Serv) linked to the productive sector; “Seller” (Sell) and “Technical/professional” (Tech/Prof) associated with occupational profile; “Certification (RUMV)” (Cer(RUMV)) and “Document granted” (DocGranted) from immigration document; “Legal” (Leg) from current immigration status; “Friend or family” (Frie) and “Offering services” (Offer) associated with “How did you get the job?”; and “None,” “discrimination” (Disc), “Salary delay,” (SaSe), and “Overtime without pay” (Over) in terms of “Have you found yourself in situations?” (Situations). In addition, for entrepreneurs, “Yes” was related to signed contract, “University academic” (Acad) corresponded to “educational level” and “Organism” (Org) and “Social media” (SocNet), from “How did you get the job?”, are distant from “Entrepreneur,” meaning that they are not significant as characteristics of the occupational category.

Regarding the occupational category employment relationship (Dependence), there are points that represent significant characteristics because they are near the category under study, such as the sector of work with “Formal” (Form), “On a fixed salary” (Fixed), and “Own account” (Own), associated with position held, whereas “On a piece-rate or job basis” (Piec) is distant. The “Yes” dot corresponding to “signed employment contract” is closer to employment relationship than to entrepreneurship. “Technician/professional” (Tech/Prof) and “Seller” (Sell) are closer than “Administrative support” (Adm), “Elementary occupation” (OcEle), and “Officer, Operator” (Oficc); “Friend or family” (Frie) associated with “How did you get the job?” is closer than “Organism” (Org), “Social media” (SocNet), and “Offering services” (Offer). For the productive sector, “Services” (Serv) is the closest, followed by “Commercial” (Com) and then “Industrial” (Ind) and “Building” (Build). For educational level, the closest to employment relationship is “University academic” (Acad) followed by “bachelor’s degree” (Bach), “Higher University Technician” (Tech), and “Primary school” (Prim).

Also, In Figure 2, the occupational category of employment relationship (Dependence) is associated with the following: “Certification (RUMV)” (CerRUMV), “Document granted” (DocGranted), and “Passport” (Pass). Further, current immigration status is associated with the “Legal” (Leg) dot. Regarding the salary earned, this is associated with “Less than minimum wage” (Less) and “1 and 3 minimum wages” (1to3MW). Furthermore, in terms of “Have you found yourself in situations?” (Situations), it is associated with the dots “None,” “Discrimination” (Disc) “Salary delay” (SaSe), and “Overtime without pay” (Over) and the types of benefit are associated with “No benefit” (Nobe) and “Salary”.

8. Discussion

As can be seen in Figure 1, the sector in which the immigrants work is associated with the occupational categories under consideration: entrepreneur or employee. Informal work is prevalent among entrepreneurs; 42 out of 45 belong to this sector. The opposite is true for those in employment, more of whom are in the formal sector, confirming the data presented in Table 1. Hence, Figure 2 shows the proximity between the informal and entrepreneur dots, while the formal dot is closer to the employment relationship dot. In addition, the occupational categories shown in Figure 1 were linked to having a signed employment contract. Therefore, those who are entrepreneurs do not have this characteristic and those who work in an employment relationship do; that is, there are cases, which is confirmed from Table 1, where there is evidence that 50% of immigrants, in a dependency relationship, have signed an employment contract. Therefore, in Figure 2, there is some distance between the two dots (employment relationship and signed contract).

Immigrant entrepreneurs tend to have a high school and primary school educational level, setting them apart from better opportunities to enter the formal labour market under an employment relationship; hence, they take the path of informal work. In the case of those who work as employees, their educational level tends to be at the university level, high school level, higher technical universities, or primary school; therefore, they had more possibilities to find such jobs, although, as observed, not all of them signed a contract. The informal situation for those in the entrepreneur category and for those who did not sign a contract within the framework of an employment relationship prevents them from the possibility of social protection, as stated by the Inter-American Development Bank (2017), which increases the informality rate in Cúcuta and further aggravates this problem in Colombia.

Moreover, Figure 1 shows the relationship between educational level, occupational profile, sector of production, and the amount earned in the last 30 days: 42 entrepreneurs and 5 employees, i.e., 85.5% of the immigrant workers, have a primary school, high school, or university education, which, as already mentioned, leads them to tend to work in the informal sector, although it must be considered that the unemployment rate for the Cúcuta Metropolitan Area is higher than the national rate and this has an impact on the formal placement of migrants. Thus, 40% of these immigrants are salesmen and 27.3% are technicians/professionals working in the commercial and service sector with low income, confirming, along with Table 1, that 80% of the workers—38 entrepreneurs and 6 employees—stated that the money they earned in the last 30 days was less than the minimum wage; therefore, they do not receive a reasonable income, despite the fact that most of them have a regular immigration status (81.8%). Further, 36 immigrant entrepreneurs and 7 employees have an immigration document.

Thus, there is a situation that does not allow for decent work with security in the workplace, as expressed by the International Labour Organization (2007). Although 63.6% of the workers stated that they had not experienced discrimination, occupational hazards, the late payment of wages, or unpaid overtime (see Table 1), not having an adequate income prevents immigrants and their families from having a good quality of life (if the families live with them) and keeps them from opportunities for personal development. Only five of the dependent workers signed an employment contract, so they enjoy labour and therefore social protection.

Notably, even though there are 45 (81.8%) immigrant workers with regular migratory status, only 11 (20%) are in the formal sector (Table 1). Thus, it is clear that there is no link between migratory status and the sector in which migrants work (Figure 1). Furthermore, regarding the signing of contracts and migration status, there is no relationship between being a legal immigrant and signing a work contract; 90.9% of the workers did not sign a work contract despite 81.8% being legal immigrants (Table 1). This can be interpreted in the sense that legal immigrants, as they are unable to find work, given that the supply of work is greater than the demand in the Metropolitan Area of Cúcuta (Ministry of Labour 2023), tend to undertake informal work, reflecting what is happening in the country in terms of informality (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2022; Castles and Miller 2004). Immigrants seek a means of subsistence (Agudelo 2019; Albornoz-Arias and Santafé-Rojas 2022; Bergner et al. 2021; Bruneau and Machado 2006; Guzi et al. 2023; cited in Kantis et al. 2004; McClelland 1989; Rogoff 2007; Vallmitjana 2014) and work in poor working conditions that alienate them from their labour rights, as Peñafiel and Rea (2022), Bravo (2022), Camas (2021), and Rubio (2014) concluded in their studies. Thus, employment or jobs for the Venezuelan immigrants under study are linked to the occupational category as self-employed or pay by piecework, as an employer, or at a fixed salary, either as an entrepreneur or in an employment relationship.

Another element considered is the lack of a relationship between the occupational category and the method of obtaining work, as approximately 60% of entrepreneurs and employees obtained work through friends and relatives: 13 immigrants offered services, 5 obtained employment through an organization, and only 3 found work through social networks (Table 1). However, the way of obtaining work was related to the occupational profile, because immigrants worked in the informal or formal sector as salesmen, technicians/professionals, officials, and operators, in elementary occupations (performing simple and routine tasks that may require the use of hand tools and enormous physical effort), or in administrative support in any of the productive sectors—trade, services, construction, or industries—confirming the relationship between the level of education, the occupational profile, and the method of obtaining work, as shown in Figure 1.

It is important to highlight that, as shown in Table 1, those who work are between the ages of 18 and 47, and only 11 were older than 47 years, indicating that immigrants of working age are being employed. In addition, of those who worked, 32 (58.2%) were female, which can be interpreted as an approach to gender equality in terms of work and the opportunities females have to meet the needs of their families, as well as the contribution they make to the productive sector.

Thus, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, it is clear that the migration and integration policies in the study area have weaknesses in that they do not include control over labour inclusion that considers decent work for those who have decided to remain in this geographic space. Evidence of this can be found in the fact that there is no relationship between the migratory status, which is mostly favourable, and the work sector, the existing informality among entrepreneurs, the fact that 50% of those who are employed do not sign an employment contract, the scarce job opportunities in the formal sector for those with a low level of education, the impossibility of having social protection for those who work informally or do not have a signed contract, and wages that are lower than those stipulated in the legislation. The way of obtaining work does not follow established paths within emerging institutional programs of migratory policies, which is visible in the study by Rubio (2014) in Colombia or by Bravo (2022) and Peñafiel and Rea (2022) in Ecuador. Therefore, migration policies, in terms of labour integration, are not exercising a relevant role. Their reformulation is necessary so that, by considering the composition of immigrants (Guzi et al. 2023), it is possible to achieve Goal 8 of the 2030 Agenda (United Nations 2015b).

9. Conclusions

In this study, two approaches to working conditions were considered: those of those who work as entrepreneurs and those who work as employees. In both approaches, there are socio-demographic conditions such as educational level and occupational profile, as well as the migration status of 81.8% of legal immigrants, which affect decent working conditions.

The 55 migrants studied did not have the opportunity to have a job compensated by a decent income, and their working conditions are not linked to the characteristics of decent work; this has become visible through informality in those considered entrepreneurs, who are mostly related to the commercial sector, obtaining a salary lower than the minimum wage, a situation that is similar for 60% of those who work as employees. In addition, there are cases of overtime worked without pay or delays in the payment of wages. Likewise, the lack of a signed contract for those who work as dependents leads to a disadvantage in working conditions, as they do not have the social security that contributes to the well-being of the worker and his or her family.

Therefore, decent work, as established in Goal 8 of the 2030 Agenda of the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations 2015a), is far from the lives of the immigrants studied, which affects their human dignity by not favouring their quality of life and that of their families; thus, decent work becomes a challenge for migration governance, as it is a commitment of the Global Compact. Immigrants require social integration to contribute to society and this will be possible if a firm stance is implemented towards their protection in terms of their labour rights. It is necessary to implement actions to monitor and control the labour activities carried out by migrants to achieve the expected conditions and benefit the population, promoting the development of the receiving country. Although the study conducted pertains to a very specific context on the Colombian-Venezuelan border, it is worth asking the question: does something similar happen in other latitudes? Is the achievement of decent work as per Goal 8 considered an important aspect of migration governance? The studies by Bravo (2022), Peñafiel and Rea (2022), Camas (2021), and Rubio (2014) show that immigrants do not have working conditions that ensure decent work, which is why the second question can be answered: in migration governance, the importance of achieving Goal 8 of the 2030 Agenda is still not given enough importance, perhaps for reasons originating in the reality of the country.

It is not a matter of surprise, it is a matter of realizing that the way we are going, we are getting used to the fact that this is the status quo and that we can continue like this. What we see with immigrant Venezuelans is part of the reality of Colombians; if the state seeks to achieve goals with respect to Goal 8 of the 2030 Agenda, it must have norms or guidelines that are being applied in the territory and they should be aligned with migration policies.

In the case we have been investigating, given the high percentage of migrants with legal migratory status who perform entrepreneurial work, there is a need for awareness programs on the importance of formalizing their activity and providing support and guidance in the process of formalizing their business or seeking financing for sustainability purposes, so that in the long term they can create jobs, pay taxes, and contribute to the economic growth of their host country. Protection agencies should also develop awareness programs for the business community on compliance with existing labour standards and their commitment to decent work as a Sustainable Development Goal to be integrated into the business culture.

The findings of this study, although limited to a sample of 55 immigrants, not only show the realities of Venezuelan immigrants, considering their capabilities from their educational level and occupational profile and the jobs they perform when they settle in Colombian territory, but also the absence of labour integration policies linked to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal on decent work, suggesting that there is still work to be done for the entities that design and implement immigration policies and for the bodies responsible for the protection of immigrants as workers.

On the other hand, as the Venezuelan migratory flow has spread to Latin American countries, this study can be replicated in other cities where migrants have settled to compare their situations and working conditions with respect to Sustainable Development Goal 8 on decent work and thus propose mechanisms, programs, and joint projects that are aligned with public policies related to the Global Compact. Perhaps, if this is done, it could give rise to a global movement that consolidates immigrants’ access to the welfare they seek when they leave their countries of origin. We believe that we must start somewhere!

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-A.C. and N.A.-A.; methodology, M.-A.C. and N.A.-A.; software, out-sourced; validation, M.-A.C., C.R.-M. and A.-K.S.-R.; formal analysis, M.-A.C. and N.A.-A.; investigation, M.-A.C., N.A.-A., C.R.-M. and A.-K.S.-R.; resources, N.A.-A.; data curation, out-sourced; writing—original draft preparation, M.-A.C. and N.A.-A.; writing—review and editing, M.-A.C., N.A.-A. and C.R.-M.; visualization, C.R.-M. and A.-K.S.-R.; supervision, M.-A.C.; project administration, N.A.-A.; funding acquisition, N.A.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Simón Bolívar (Colombia) grant number C2060020822.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project from which this study was derived had the ethics review and approval of the institutional ethics committee. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the SIMÓN BOLÍVAR UNIVERSITY (COLOMBIA) (In compliance with the Committee’s recommendations, the endorsement of the Project CIE-USB-0413-00, was legalized by Act of Project Approval No.00362 of 22 August 2022) for studies in humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Albornoz-Arias, Neida; Cuberos, Maria Antonia; Ramirez Martínez, Carolina; SANTAFÉ, AKE-VER (2023), “Situation and perceptions of Venezuelan migrants settled in Cúcuta, La Parada and Los Patios de Norte de Santander, Colombia.”, Simon Bolivar University, V1, doi:10.17632/tw2pxrvxtt.1.

Acknowledgments

We thank those who collaborated in the data collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not report any potential conflict of interest.

References

- Agudelo, Juan C. 2019. Impact of Migration on Citizen Security in Cali. Specialization in Security Administration. Bogotá: Universidad Militar Nueva Granada. Available online: https://repository.unimilitar.edu.co/bitstream/handle/10654/21136/AgudeloVargasJuanCarlos2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Albornoz-Arias, Neida, and Akever K. Santafé-Rojas. 2022. Self-confidence of Venezuelan migrant entrepreneurs in Colombia. Social Sciences 11: 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergner, Sabine, Julia Auburger, and Dominik Paleczek. 2021. The why and the how: A nexus on how opportunity, risk and personality affect entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitar, Sebastián. 2022. Migration in Colombia and Public Policy Responses. Public Policy Paper Series (34). UNDP Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2022-11/PNUDLAC-working-paper-34-Colombia-ES.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Bravo, Christian. 2022. Consequences of the Informal Work of Illegal Venezuelan Migrants in Ecuador. Undergraduate thesis, Catholic University of Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador. Available online: https://dspace.ucacue.edu.ec/bitstream/ucacue/12470/1/TESIS%20ANDRES%20BRAVO.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Bruneau, Juanita, and Hilka Machado. 2006. Entrepreneurship in Latin American countries based on Global Entrepreneurship indicators. Panorama Socioeconómico 24: 18–25. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/399/39903303.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Camarero, Luis A. 2010. Family Transnationality: Family Transnationality: Family Structures and Migrants’ Trajectories of Regroupation in Spain. EMPIRIA. Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales 19: 39–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camas, Ferrán. 2021. Obstacles of labour legislation and the legal regime of foreigners in the achievement of decent work for migrant domestic workers. Lex Social: Revista De Derechos Sociales 11: 449–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, Gerardo D. 2012. Employment, Remuneration and Severance Pay (in Argentine Law). XXXIV National Conference of Professional Practice Professors. Available online: https://www.economicas.uba.ar/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/CECONTA_SIMPOSIOS_T_2012_A1_CANALES_DEPENDENCIA_.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Castilla-Vázquez, Carmen. 2017. Women in transition: African female immigration in Spain. Migraciones Internacionales 9: 143–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castles, Stephen, and Mark J. Miller. 2004. The Age of Migration. International Population Movements in the Modern World. Translation Luis Rodolfo Morán Quiroz. Available online: http://biblioteca.diputados.gob.mx/janium/bv/ce/scpd/LIX/era_mig.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Cely, Gilberto. 2009. Global Bioethics. Madrid: Siglo del hombre editores. [Google Scholar]

- Cerruti, Marcela. 2020. 5 Outstanding Features of Intra-Regional Migration in South América. Available online: https://migrationdataportal.org/es/blog/5-rasgos-destacados-de-la-migracion-intra-regional-en-americadel-sur (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- Congress of the Republic of Colombia. 2013. Law 1625 of 2013. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=52972#:~:text=Dicta%20normas%20org%20C3%A1nicas%20para%20dotar,para%20cumplir%20con%20con%20sus%20sus%20sus%20funciones (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Congress of the Republic of Colombia. 2021. Law 2136 of 2021; Official Gazette No. 51.756 of 4 August 2021. Available online: https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/Normograma/docs/ley_2136_2021.htm#:~:text=Ministerio%20de%20Relacio-nes%20Exteriores%20%2D%20Normograma,2136%20de%20202021%20Congreso%20Nacional%5D&text=Por%20medio%20de%20de%20la%20cual,y%20se%20dictan%20otras%20disposici%C3%B3n%20otras%20disposiciones (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Cúcuta Chamber of Commerce. 2023. Labour Market Informality June 2023. Available online: https://datacucuta.com/indicadores-regionales/mercado-laboral/mercado-laboral-informalidad-junio-2023/ (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- David, Anda, and Jarreau Joachim. 2016. Determinant of Emigration: Evidence from Egypt. Egypt: Economic Research Forum (ERF). Available online: https://erf.org.eg/app/uploads/2016/04/987.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2023).

- Dibeh, Ghassan, Alí Fakih, and Walid Marrouch. 2018. Decision to emigrate amongst the Youth in Lebanon. International Migration 56: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, Melisa. 2019. To Work as an Employee or to Be Self-Employed, That Is the Question. Undergraduate thesis, Juan Agustín Maza University, Mendoza, Argentina. Available online: http://repositorio.umaza.edu.ar/bitstream/handle/00261/1761/Echegaray%20Melisa_TRABAJAR%20EN%20RELACI%C3%93N%20DE%20DEPENDENCIA%20O%20SER%20INDEPENDIENTE,%20ESA%20ES%20LA%20CUESTI%C3%93N_2019.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Fernández, Beatriz, and Tatiana Paravic. 2003. Level of job satisfaction among nurses in public and private hospitals in the province of Concepción, Chile. Ciencia y Enfermería 9: 57–66. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/pdf/cienf/v9n2/art06.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Ferreira, Francisco H. G., Shaohua Chen, Andrew Dabalen, Yuri Dikhanov, Nada Hamadeh, Dean Jolliffe, Ambar Narayan, Esper B. Prydz, Ana Revenga, Prem Sangraula, and et al. 2015. A Global Count of the Extreme Poor in 2012: Data Issues, Methodology, and Initial Results. Policy Research Working Paper. (7432). Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/22854/A0global0count00and0initial0results.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Guzi, Martin, Matin Kahanec, and Lucía Kureková. 2023. The impact of immigration and integration policies on the labour market hierarchies of native immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 49: 4169–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Roberto, Carlos Fernández, and Pilar Baptista. 2010. Research Methodology. México: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela. 2023. Refugees and migrants from Venezuela. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/refugiadosymigrantes (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Inter-American Development Bank. 2017. Better Jobs Index: Latin American Working Conditions Index. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/es/indice-de-mejores-trabajos-indice-de-condiciones-laborales-de-america-latina (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- International Labour Office. 2004. Report VI. Seeking a fair deal for migrant workers in the globalised economy. Paper presented at the International Labour Conference, 92nd Session, Geneva, Switzerland, June 1–12; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/spanish/standards/relm/ilc/ilc92/pdf/rep-vi.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- International Labour Organization. 2007. Toolkit for Mainstreaming Employment and Decent Work. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization. n.d. The Working Relationship. Available online: https://ilo.org/ifpdial/areas-of-work/labour-law/WCMS_165190/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- International Organization for Migration. 2019. IOM Glossary on Migration. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml-34-glossary-es.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Kantis, Hugo, Pablo Angelelli, and Virginia Moori, eds. 2004. Entrepreneurial Development. Latin America and International Experience. New York: Inter-American Development Bank. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/442/Desarrollo%20emprendedor.pdf?sequence=2 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Laajimi, Rawaa, and Julie Le Gallo. 2022. Push and pull factors in Tunisian internal migration: The role of human capital. Growth and Change 53: 771–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levaggi, Virgilio. 2004. What Is Decent Work? Available online: https://www.ilo.org/americas/sala-de-prensa/WCMS_LIM_653_SP/lang--es/index.htm#:~:text=Virgilio%20Levaggi%20(*),humana%20m%C3%A1s%20amplia%20que%20aquel (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Maldonado, Juan P. n.d. Overcoming the Classical Concept of the Employment Contract. Conferencia Nacional Tripartita. El Future del Trabajo que Queremos. 2. p. 28. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---europe/---ro-geneva/---ilo-madrid/documents/article/wcms_548602.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Martínez, Víctor M. 2013. Reflections on human dignity today. Boletín Mexicano de Derecho Comparado 46: 39–67. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/bmdc/v46n136/v46n136a2.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2023).

- Mazuera-Arias, Rina, Neida Albornoz-Arias, María A. Cuberos, Marisela Vivas-García, and Miguel A. Morffe Peraza. 2020. Sociodemographic profiles and the causes of regular Venezuelan Emigration. International Migration 58: 164–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, David. 1989. Study of Human Motivation. Madrid: Narcea. [Google Scholar]

- Meulman, Jacqueline, and Willem Heiser. 2010. IBM SPSS Categories 19. Available online: https://www.unileon.es/ficheros/servicios/informatica/spss/spanish/IBM-SPSS_categorias.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Migration Colombia. 2022. Distribution of Venezuelans in Colombia—Cut-Off 28 February 2022. Available online: https://www.migracioncolombia.gov.co/infografias/distribucion-de-venezolanos-en-colombia-corte28-de-febrero-de-2022 (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Milasi, Santo. 2020. What drives youth’s intention to migrate abroad? Evidence from International Survey Data. IZA Journal of Development and Migration 11: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia. 2021. Decree 216 (March 1); Official Gazette No. 51.603 of 1 March 2021. Available online: https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/sites/default/files/Normograma/docs/decreto_0216_2021.htm (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Colombia. 2022. The National Government and the Interagency Group on Mixed Migration Flows launch the Colombia Chapter of the Regional Response Plan for Refugees and Migrants 2023–2024. Available online: https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/newsroom/news/gobierno-nacional-grupo-interagencial-flujos-migratorios-mixtos-lanzan-capitulo (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Ministry of Labour. 2018. Resolution 4386 of 9 October 2018; By Which the Single Registry of Foreign Workers in Colombia Is Created and Implemented. Available online: https://www.mintrabajo.gov.co/documents/20147/58634564/Resoluci%C3%B3n+4386+de+2018.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Ministry of Labour. 2023. Territorial Context of Norte de Santander. Available online: https://publicacionessampl.mintrabajo.gov.co/sampl-repo/api/core/bitstreams/5e95b197-9b0f-45c3-b30a-604b1163b581/content (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- National Administrative Department of Statistics. 2023. Relevant Indicators. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema#:~:text=Demograf%C3%ADa%20y%20poblaci%C3%B3n (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- National Council for Economic and Social Policy. 2018. CONPES Document 3950. Strategy for the Attention of Migration from Venezuela. Available online: https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/documento-conpes-estrategia-atencion-migracion-venezuela (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- National Council for Economic and Social Policy. 2022. Document CONPES 4100. Strategy for the Integration of the Venezuelan Migrant Population as a Factor of Development for the Country. Available online: https://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=126117 (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2022. Tackling Informality in Colombia with the Social and Solidarity Economy. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/social-economy/tackling-informality-in-colombia-with-the-social-and-solidarity-economy.htm (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Peñafiel, Fernando, and Pedro Rea. 2022. New Paradigms of Informal Work: The Case of Venezuelan Migrants and Labour Rights in the Business Sector in Riobamba. Undergraduate thesis, National University of Chimborazo, Riobamba, Ecuador. Available online: http://dspace.unach.edu.ec/bitstream/51000/10365/1/Rea%20Estrada%2c%20P.%282023%29%20Nuevos%20paradigmas%20del%20trabajo%20informal%20caso%20los%20migrantes%20venezolanos%20frente%20a%20los%20derechos%20laborales%20en%20el%20sector%20empresarial%20de%20Riobamba.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Pérez, César. 2004. Multivariate Data Analysis Techniques. Madrid: Pearson Education. Available online: https://gc.scalahed.com/recursos/files/r161r/w25172w/Tecnicas_de_analisis_multivariante.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2023).

- Robbins, Stephen P., and Timothy A. Judge. 2009. Organizational Behaviour. México: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, Edward. 2007. Opportunities for Entrepreneurship in Later Life. Generations 31: 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, María V. 2014. Informal work in Colombia and its impact on Latin America. Labour Observatory Venezuelan Journal 7: 23–40. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2190/219030399002.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Samaniego-Erazo, Carmen, Luz Vallejo, Janeth Morocho, and Florípes Samaniego. 2020. Incidence of external immigration in the informal economy. Venezuelan Journal of Management 25: 1517–29. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/290/29065286015/29065286015.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- The Venezuelan. 2023. How Many Venezuelans Live in Cúcuta and Where Do They Live? Available online: https://elvenezolanocolombia.com/2023/04/20-de-la-poblacion-de-cucuta-son-migrantes-venezolanos/ (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Together We Can Foundation. 2023. Analysis of the Migratory Context in Cúcuta: Border Points, International Cooperation and Migrant Population (May 2023). Available online: https://www.juntossepuede.co/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Analisis-contexto-migratorio-Cucuta.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- United Nations. 2015a. Decent Work and Economic Growth: Why It Matters. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/10/8_Spanish_Why_it_Matters.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- United Nations. 2015b. Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 8 Decent Work and Economic Growth. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/economic-growth/ (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 2023. Local Situation Report, GIFMM Norte de Santander, January–February 2023. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/colombia/reporte-situacional-local-gifmm-norte-de-santander-enero-febrero-2023 (accessed on 8 September 2023).

- Vallmitjana, Núria. 2014. The Entrepreneurial Activity of IQS Graduates. Doctoral thesis, Universitat Ramón Llul, Barcelona, Spain. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/145034 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- World Bank. 2022. Review: Adjustment in World Poverty Lines. Available online: https://www.bancomundial.org/es/news/factsheet/2022/05/02/fact-sheet-an-adjustment-to-global-poverty-lines#:~:text=La%20nueva%20l%C3%ADnea%20mundial%20de,se%20encontraban%20en%20esta%20situaci%C3%B3n (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Zisi, Alma, Bitila Shosha, and Armela Anamali. 2022. The Empirical Evidence on Albanian Youth Migration. Journal Transition Studies Review 29: 127–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).