3. Results

Correlational analyses were used to analyze the associations between self-esteem and sibling violence (perpetration and victimization). The results of the inter-scale correlations and the respective means and standard deviations are presented in

Table 1.

Regarding the association between self-esteem and the perpetration of sibling violence, there is a positive and significant correlation of a low magnitude for negotiation (r = 0.21, p < 0.001) and negative and significant correlations of a low magnitude for psychological aggression (r = −0.19, p < 0.001), for physical assault (r = −0.18, p < 0.001), for sexual coercion (r = −0.15, p < 0.05) and for injury (r = −0.18, p < 0.001).

Regarding the association between self-esteem and the victimization of sibling violence, there is a positive and significant correlation of a low magnitude of negotiation (r = 0.24, p < 0.001), with psychological aggression (r = −0.19, p < 0.001), physical assault (r = −0.18, p < 0.001), and injury (r = −0.21, p < 0.001) which is correlated negatively and significantly with a low magnitude. Sexual coercion is the only dimension that is not statistically significantly correlated.

3.1. Variance of Self-Esteem and Sibling Violence According to Sex, Social Class and Position in the Sibling Dyad

Aiming at analyzing self-esteem and sibling violence as a function of sociodemographic variables (sex, social class and position in the sibling dyad), we proceeded with univariate and multivariate differential analyses of variance (ANOVA and MANOVA), as well a Student’s t-test.

To explore differences for the variable self-esteem as a function of sex, a student’s t-test was used and the results suggest the absence of significant differences t(284) = 0.90; p = 0.37; IC 95% [−0.08; 0.20] ƞ2 = 0.04.

Regarding the perpetration of sibling violence, significant differences are found in relation to sex for the dimensions of negotiation

t(284) = −2.05;

p = 0.04; IC 95% [−0.81;−0.02] ƞ

2 = 0.20, psychological aggression

t(284) = −2.02;

p = 0.05; IC 95% [−0.57;−0.01] ƞ

2 = 0.30 and sexual coercion

t(152.52) = 2.58;

p = 0.01; IC 95% [0.02;0.18] ƞ

2 = 0.50. Thus, it is verified that females use more negotiation (

M = 3.20,

SD = 1.59), but also psychological aggression (

M = 1.21,

SD = 1.25), while males more often perform acts of sexual coercion (

M = 0.14,

SD = 0.39) (

Table 2). Finally, physical assault

t(284) = −0.22;

p = 0.83; IC 95% [−0.17;0.14] ƞ

2 = 0.05 and injury

t(214.59) = 1.31;

p = 0.19; IC 95% [−0.03;0.16] ƞ

2 = 0.02 do not present significant differences regarding sex (

Table 2).

Regarding the victimization of sibling violence according to sex, there are significant differences for psychological aggression

t(269.90) = −2.21;

p = 0.03; IC 95% [−0.58;−0.03] ƞ

2 = 0.40 and injury

t(182.86) = 2.05;

p = 0.04; IC 95% [0.00;0.22] ƞ

2 = 0.60. Thus, it is concluded that females are the ones who suffer more psychological aggression (

M = 1.14,

SD = 1.26), while males are the ones who suffer the most acts of injury (

M = 0.24,

SD = 0.52) (

Table 2). The dimensions of negotiation

t(284) = −1.54;

p = 0.13; IC 95% [−0.70;0.09] ƞ

2 = 0.02, physical assault

t(284) = 0.52;

p = 0.60; IC 95% [−0.12;0.21] ƞ

2 = 0.07 and sexual coercion

t(284) = 0.74;

p = 0.46; IC 95% [−0.04;0.22] ƞ

2 = 0.07 do not demonstrate statistically significant differences regarding sex (

Table 2).

Social class was classified according to the average monthly income of the parents. This categorization was made in three groups: low (up to and including the minimum wage), medium (from the minimum wage to 1000 euros) and high (more than 1000 euros per month). This division was based on the five-level classification on the Graffar household income scale. In the present study, these five levels were adapted into only three (low, medium and high) to simplify and be better understood by the respondents.

A univariate differential analysis (ANOVA) was carried out to investigate self-esteem as a function of social class. The results suggest that there are no significant differences: F(2, 221) = 2.13, p = 0.12.

Regarding sibling violence in relation to social class, there are no significant differences in both the perpetration F(10, 436) = 0.99, p = 0.45, ƞ2 = 0.53 or victimization subscales F(10, 436) = 0.63, p = 0.79, ƞ2 = 0.33.

By analyzing self-esteem as a function of position in the sibling dyad, it is evident that there are no significant differences F(2, 283) = 0.29, p = 0.75.

Regarding the subscale perpetration of sibling violence, no statistically significant differences were found F(10, 560) = 1.36, p = 0.20, ƞ2 = 0.70 faced with the position in the sibling dyad.

Regarding the subscale victimization of sibling violence

F(10, 560) = 2.71,

p = 0.003, ƞ

2 = 0.97, there are significant differences in the position in the sibling dyad only for the dimension of physical assault

F(2, 283) = 5.42,

p = 0.005, ƞ

2 = 0.84. Middle siblings (

M = 0.72,

SD = 0.98) experience more physical assault (victimization subscale) when compared to youngest sibling (

M = 0.40,

SD = 0.70) and older sibling (

M = 0.28,

SD = 0.45) (

Table 3).

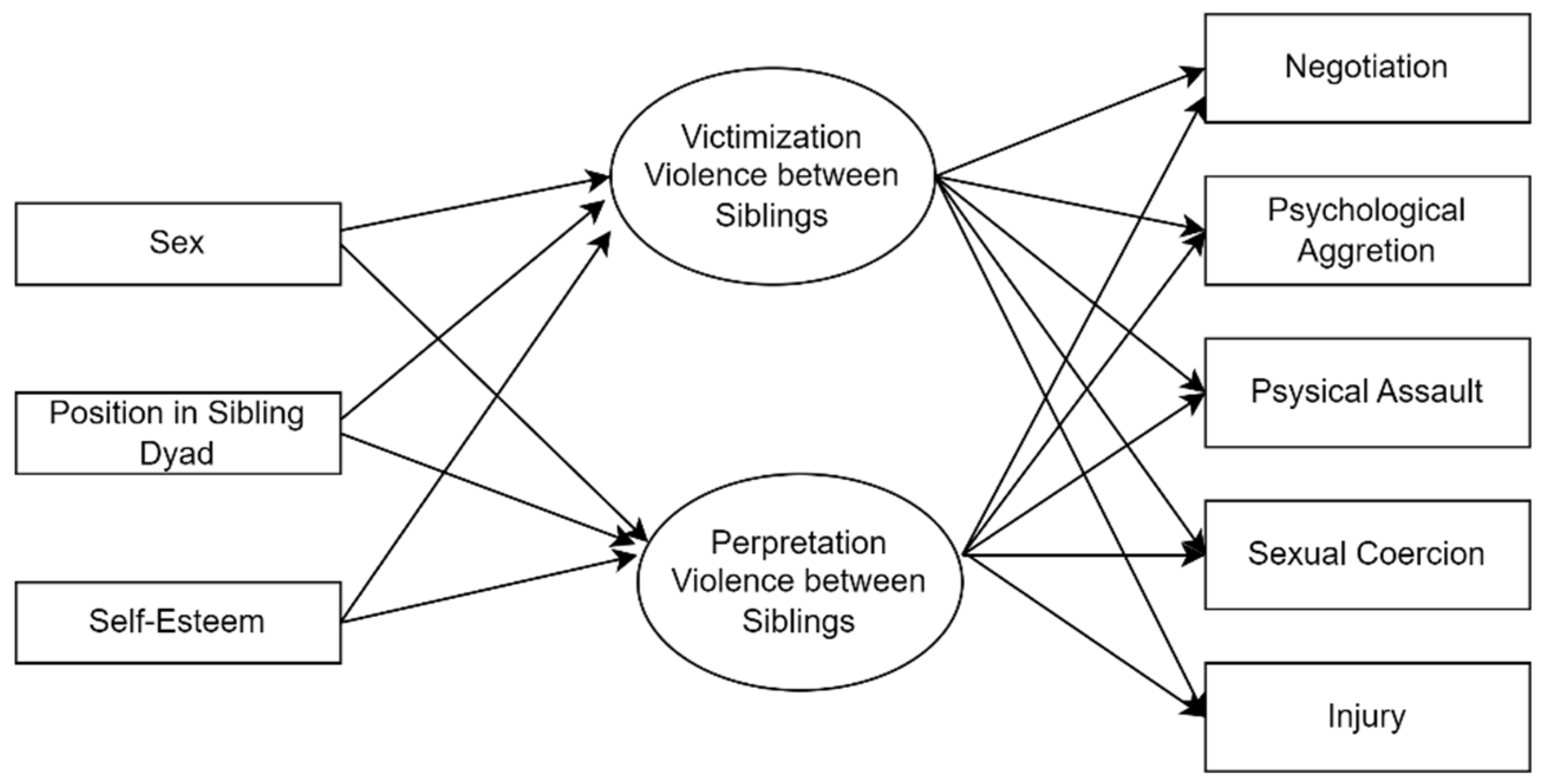

3.2. Predictive Role of Sex, Position in Sibling Dyad and Self-Esteem in Sibling Violence

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed to ensure the response to the present study’s objectives.

In the performance of each hierarchical multiple regression, the dimensions of violence between siblings were analyzed separately. All analyses introduced the following three blocks: sex, position in the sibling dyad and self-esteem. Note that the variables sex and position in the sibling dyad were dummy coded to ensure the analysis of sex (0—male, 1—female) and position in the sibling dyad (1—Youngest sibling; 2—Middle sibling; 3—Eldest sibling).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding the negotiation (perpetration), sex makes a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 4.21, p = 0.041, explains 2% of the total variance (R2 = 0.02) and contributes individually to 1% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.01). The position in the sibling dyad makes a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 3.02, p = 0.03, explains 3% of variance (R2 = 0.03) and contributes individually to 2% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.02). Self-esteem makes a significant contribution, F(4, 281) = 5.96, p = 0.000, explains 8% of variance (R2 = 0.08) and contributes individually to 7% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.07).

By analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that three have a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as an effect of negotiation (perpetration), presenting itself according to its importance: self-esteem (β = 0.22), position in sibling dyad—youngest (β = −0.20)—and females (β = 0.13) (

Table 4).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding psychological aggression (perpetration), sex makes a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 4.06, p = 0.045, explains 1% of variance (R2 = 0.01) and contributes individually to 1% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.01). The position in the sibling dyad makes a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 3.13, p = 0.026, explains 3% of variance (R2 = 0.03) and individually contributes 2% to the model (R2change = 0.02). No que concerns self-esteem as it makes a significant contribution F(4, 281) = 4.76, p = 0.001, explains 6% of variance (R2 = 0.06) and individually contributes 5% to the model (R2change = 0.05).

Analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that two make a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as an effect of psychological aggression (perpetration), presenting itself according to its importance: position in the sibling dyad—older sibling (β = −0.20)—and self-esteem (β = −0.18) (

Table 4).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding physical assault (perpetration), sex does not make a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 0.05, p = 0.827, does not explain the variance (R2 = 0.00) and does not present an individual contribution to the variance of the model (R2change = 0.00). The position in the sibling dyad does not make a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 0.89, p = 0.448, explains 1% of variance (R2 = 0.01) and does not contribute individually to the template (R2change = 0.00). Self-esteem makes a significant contribution, F(4, 281) = 3.04, p = 0.018, explains 4% of variance (R2 = 0.04) and contributes individually to 3% to the model (R2change = 0.03).

By analyzing the individual contribution of the independent variable, it is observed that self-esteem (β = −0.18) has a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) associated with physical assault (perpetration) (

Table 4).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding sexual coercion (perpetration) sex makes a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 8.46, p = 0.004, explains 3% of variance (R2 = 0.03) and contributes individually to 3% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.03). The position in the sibling dyad makes a significant contribution F(3, 282) = 3.12, p = 0.027, explains 3% of variance (R2 = 0.03) and contributes individually to 2% of the model (R2change = 0.02). Self-esteem also makes a significant contribution, F(4, 281) = 4.12, p = 0.003, explains 6% of variance (R2 = 0.06) and contributes individually to 4% of the model (R2change = 0.04).

By analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that two make a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as the effect of sexual coercion (perpetration), males (β = −0.17) and self-esteem (β = −0.15) (

Table 4).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding injury (perpetration), sex does not make a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 1.085, p = 0.175, explains 1% of the variance (R2 = 0.01) and does not present an individual contribution to the variance of the model (R2change = 0.00). The position in the sibling dyad does not make a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 1.37, p = 0.253, explains 1% of variance (R2 = 0.01) and does not contribute individually to the template (R2change = 0.00). Regarding self-esteem, it makes a significant contribution, F(4, 281) = 3.46, p = 0.009, explains 5% of variance (R2 = 0.05) and contributes, individually, 3% to the model (R2change = 0.03).

By analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that only self-esteem (β = −0.18) makes a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as the effect of injury (perpetration) (

Table 4).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding negotiation (victimization) sex (dummy) does not make a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 2.37, p = 0.125, explains 1% of the total variance (R2 = 0.01) and contributes individually to 1% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.01). Regarding the position in the sibling dyad (dummy), it does not make a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 1.69, p = 0.170, explains 1% of variance (R2 = 0.01) and contributes individually to 1% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.01). With regard to self-esteem, it makes a significant contribution, F(4, 281) = 5.75, p = 0.000, explains 6% of variance (R2 = 0.06) and contributes individually to 6% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.06).

By analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that self-esteem (β = 0.24) makes a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as the effect of negotiation (

Table 5).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis of psychological aggression (victimization), sex makes a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 4.57, p = 0.033, explains 2% of the variance (R2 = 0.02) and contributes individually to 1% of the variance for the model (R2change = 0.01). The position in the sibling dyad makes a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 2.98, p = 0.0232, explains 3% of the variance (R2 = 0.03) and individually contributes 2% to the model (R2change = 0.02). Regarding self-esteem, it makes a significant contribution, F(4, 281) = 4.57, p = 0.001, explains 6% of the variance (R2 = 0.06) and contributes individually to 5% of the model (R2change = 0.05).

By analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that two make a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as the effect of psychological aggression (victimization), with both presenting the same importance: position in the sibling dyad—eldest sibling (β = −0.18)—and self-esteem (β = −0.18) (

Table 5).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis of physical assault (victimization), sex does not make a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 0.27, p = 0.602, does not explain the variance (R2 = 0.00) and does not present an individual contribution to the variance of the model (R2change = 0.00). Regarding the position in the sibling dyad, it makes a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 3.73, p = 0.012, explains 4% of variance (R2 = 0.04) and contributes individually to 3% of the model (R2change = 0.03). Regarding self-esteem, it makes a significant contribution, F(4, 281) = 5.08, p = 0.001, explains 7% of variance (R2 = 0.07) and contributes individually to 5% of the model (R2change = 0.05).

By analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that three make a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as the effect of physical assault (victimization), presenting themselves according to their importance: position in the sibling dyad—youngest sibling (β = −0.29)—position in the sibling dyad—Eldest sibling (β = −0.24)—and self-esteem (β = −0.17) (

Table 5).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding sexual coercion (victimization), sex does not make a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 0.55, p = 0.459, does not explain the variance (R2 = 0.00) and does not individually contribute variance to the model (R2change = 0.003). With regard to the position in the sibling dyad, it does not make a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 0.37, p = 0.772, does not explain the variance (R2 = 0.00) and contributes individually to −1% of the model (R2change = −0.01). Regarding self-esteem, it makes no significant contribution, F(4, 281) = 0.31, p = 0.871, does not explain the variance (R2 = 0.00) and contributes individually to −1% of the model (R2change = −0.01).

By analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that none make a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as an effect of sexual coercion (victimization) (

Table 5).

In the hierarchical multiple regression analysis regarding injury (victimization), sex makes a significant contribution, F(1, 284) = 4.85, p = 0.028, explains 2% of variance (R2 = 0.02) and contributes individually to 1% for model variance (R2change = 0.01). Regarding the position in the sibling dyad, it does not make a significant contribution, F(3, 282) = 2.22, p = 0.086, explains 2% of variance (R2 = 0.02) and individually contributes 1% to the model (R2change = 0.01). Regarding self-esteem, it makes a significant contribution F(4, 281) = 5.08, p = 0.001, explains 7% of variance (R2 = 0.07) and individually contributes 5% to the model (R2change = 0.05).

Analyzing the individual contribution of each independent variable, it is observed that two have a significant contribution (

p < 0.05) as the effect of injury (victimization), presenting itself according to its importance: self-esteem (β = −0.21) and males (β = −0.14) (

Table 5).

4. Discussion

The main objective of the present study was to test the effect of sex, position in the sibling dyad and self-esteem in the development of behaviors of violence between siblings. The results suggest that self-esteem is positively associated with negotiation on the perpetration and victimization of sibling violence. On the contrary, it is negatively associated with psychological aggression, physical assault and injury, also concerning the perpetration and victimization of sibling violence. Only about sexual coercion is self-esteem negatively associated with perpetration and there is no significant relationship with victimization. Thus, self-esteem seems to play an important role in the dynamics of violence between siblings. The presence of a positive perception of oneself (

Serra 1988) seems to favor the establishment of dialogues between brothers and, consequently, to benefit the capacity to resolve conflicts that may arise between them. Self-esteem it also seems to be associated with aggressive conduct between siblings playing a protective role. When there is high self-esteem, there is a lower frequency of aggressive acts perpetrated and suffered by siblings. Knowing that self-esteem consists in the appreciation that the subject makes of himself, contemplating his attributes and qualities, having himself as capable or incapable of successfully executing what he proposes (

Serra 1988), an individual with high self-esteem, demonstrating high levels of happiness and satisfaction with himself, will not have the need to develop any rivalry, which assumes a violent character, towards any of his siblings (

Mota et al. 2017). The results of the present study are in accordance with previous studies.

Yeh and Lempers (

2004), in a sample of 374 families, found that a healthy relationship between siblings was predictive of high self-esteem because, by relating positively and adjusted, they developed positive feelings and perceptions about themselves. Also, in their research,

Avanci et al. (

2007) and

Wiehe (

1997) realized that low self-esteem characterizes siblings involved in violent behavior.

Avanci et al. (

2007), in a sample of 266 students aged between 11 and 19 years, also found that adolescents with high self-esteem engage less in victimizing behaviors in sibling violence.

Wiehe (

1997), in addition to verifying this assumption, also found that brother aggressors in their dyad have low levels of self-esteem.

Regarding self-esteem, there were no significant differences according to sex. It is suggested that the results obtained in the present research are attributed to the fact of evaluating global self-esteem and not considering the various specificities of it (e.g., sexual, physical and academic) because an adolescent, in general, may not evaluate himself positively; however, he can be considered effective in some specificities (e.g., academic self-esteem). The study of

Gentile et al. (

2009) points in the same direction. The authors consider that to obtain significant results in this analysis and properly examining self-esteem, the specific self-esteem should always be considered. Although the results of the present investigation do not generate consensus in the literature (e.g.,

Quatman and Watson 2001;

Ruiz et al. 2009), they are corroborated by

Ruiz et al. (

2009) in a sample of 1319 adolescents aged between 11 and 16 years and they, in their study, also verified the absence of significant differences in self-esteem in relation to sex.

Regarding negotiation, psychological aggression and sexual coercion in the perpetration of violence between siblings, there were significant differences according to sex. Female subjects showed a greater predisposition to establish conversations with their siblings and the elements most resort to psychological aggressions. Therefore, males are the one who most use sexual assaults. In view of these results, it was expected that the female was more involved in negotiation behaviors. This can be explained based on empirical conceptions about sex differences. According to

Rubia (

2007), females, when compared to males, seem to have a greater capacity in relation to the performance of verbal skills. In addition, it is also known that the development of these same communicative skills progresses later in males, unlike females, who previously acquire a greater maturation of social skills (

Legato 2009). In the follow-up, sex stereotypes created by society also seem to influence the greater involvement of females in negotiation behaviors. From its birth, the baby is exposed to certain behaviors taken to the detriment of its sex, according to

Seixas (

2009). From an early age, parents show different behaviors towards babies based on their sex. When faced with a female baby, parents tend to show more concern for others and engage in longer conversations than a male baby. This behavior is believed to contribute to aggressive behavior in boys (

Kindlon and Thompson 2000). Females tend to adopt psychological aggression behaviors more often than males, suggesting that societal sex stereotypes play a significant role. While males are expected to display harsh and aggressive behavior, the same is not expected from females.

Females are expected to display indirect behavior characterized by subtlety (

Simões et al. 2015). Therefore, knowing that psychological aggression is an indirect form of being aggressive toward a sibling, it was expected that individuals identifying as female would choose this type of aggression. However, the current results contradict the existing literature on the subject, which assigns the role of aggressor in violence between siblings to males (

Kiselica and Morrill-Richards 2007).

Kiselica and Morrill-Richards (

2007) justify that such results are due to sex stereotypes, in which aggressiveness is once again associated with males and subtlety with females. Thus, the father figures infer that the damage caused by males is the most serious. This is because they see it according to sex stereotypes, in which males are the most physically aggressive and these physical damages are visible. As for females, they infer that they do not have sufficient strength to cause serious harm to their siblings. According to

Kiselica and Morrill-Richards (

2007), it is only by changing attitudes and accepting that it is that females perpetrate aggression against a sibling that this type of family violence can be tackled. Additionally, sex stereotypes already mentioned in this discussion also justify the greater involvement of males as an aggressor in sexual coercion. However, attention should also be paid to the inequality of power mentioned in the definition of sibling violence. It is understood that this inequality of power can be related to several characteristics of the actors; among them age, height, physical strength and superiority are specific to the aggressor (

Monks et al. 2009). In this sense, physical superiority is seen as belonging to males when compared to females, which corresponds to sex stereotypes (

Kiselica and Morrill-Richards 2007;

Simões et al. 2015). It was expected that sexual assaults would be perpetrated primarily by males. The present results corroborate the existing literature on the subject, through which it can be observed that males more frequently maintain sexual acts (with siblings) without consent (e.g.,

Relva et al. 2013;

Relva et al. 2014).

Regarding psychological aggression and injury in the victimization of sibling violence in relation to sex, there were significant differences, with females showing a greater propensity to victimize psychological aggressions. In contrast, the males showed greater victimization of aggressive behaviors causing serious physical harm. Regarding the victimization of psychological aggression, experienced mostly by females, it is suggested that this is justified based on the conception that there is reciprocity in sibling violence (

Krienert and Walsh 2011). In the present research, females are the ones that most perpetrate violence of the psychological type because, considering males are seen often with a greater physical robustness (

Wiehe 1997), females are expected to opt for psychological violence. In addition, as already mentioned, according to

Krienert and Walsh (

2011), there is a reciprocity in sibling violence; in a way, they are both victims and perpetrators of aggression. Thus, and verified, this duality would be expected to be attributed to the same sex the same type of violence suffered and perpetrated. The present results are corroborated by the literature (e.g.,

Khan and Rogers 2015;

Relva et al. 2013;

Simonelli et al. 2002) when other researchers verified a predominance of females being victims of psychological aggression. The results of being a victim of injury (physical aggression with severe physical damage) seem to involve males exercising them, mostly in aggressive behaviors towards those of the same sex (

Relva et al. 2014). Also, the existing literature on the subject points results in the same outcome. Several studies show that male siblings are more victimized by assaults with serious physical harm (

Relva et al. 2013;

Relva et al. 2014).

In view of the results obtained in the present study, it was also found that there were no significant differences in self-esteem as a function of social class. According to the existing literature on the subject, such results were unexpected.

Espínola (

2010), in a sample of 593 students aged between 9 and 13 years, found that compared to individuals belonging to the low social class, subjects who were included in the average socioeconomic level have higher rates of self-esteem. However, these results are due to the particularities of the sample of the present investigation. Notably, 44.4% of the respondents belong to the middle social class, making it impossible to have a proportional distribution across all levels (low, medium and high) and an exact theme analysis.

The results also point to the absence of significant differences in victimization and the perpetration of sibling violence regarding the parents’ social class. As mentioned, social class does not seem to predict sibling bullying (

Dantchev and Wolke 2019). Thus, it is suggested that the results are related to the size of the sample and its distribution relative to the socioeconomic level of the parents. In the present study, 44.4% of the adolescents in the sample were in the middle class, 20.3% in the high social class and the remainder in the so-called low social class. It should be noted that a larger sample that contemplates, in equal ways, different social classes should obtain a better analysis of this theme.

Hoffman and Edwards (

2004) recognize the gap in the literature on the subject. According to the authors, the studies that contemplate the parents’ social class in their analyses are scarce because, as in the present investigation, they present a limited sample and mostly belong to the middle social class, thus opting for the analysis of variables such as sex and age. However,

Green (

1984), aiming to detect and analyze the characteristics of children, as well as their parents, who assaulted siblings, causing them serious damage, in a sample of five children and adolescents, could infer that the severity of injuries increased when there were fewer financial resources. Indeed, in 2015, Tippet and Wolke found that greater rates of sibling aggression were associated with financial difficulties. In this follow-up, it is also suggested that because the sample of this study includes few elements of low social class, more obstacles are denoted to the existence of significant differences.

Regarding self-esteem in relation to the position in the sibling dyad, there were no significant differences. It is suggested that such conceptions may be explained based on the present study’s sample. It should be noted that the distribution of adolescents by the position occupied in their phratry is quite divergent since 57% of the respondents are characterized by being older siblings, only 12.2% are from the middle and the rest are the youngest. According to the literature, it would be expected that there will be differences in self-esteem inherent to the position occupied in the phratry. According to

Fernandes (

2005), the middle sibling is the one who presents lower self-esteem due to the poorly defined role occupied in his sibling dyad and consequent feelings of inferiority in relation to his siblings.

There were no significant differences in the perpetration of sibling violence in the face of their position in the sibling dyad. It is suggested that the achievement of such results is due to the non-association of the position occupied by the aggressor sibling with the position occupied by the victim of these same aggressions. The existing literature (

Menesini et al. 2010) attaches importance to this analysis, verifying the presence of significant differences in sibling violence due to the position occupied by the sibling in the dyad. However, these analyses contemplate the position occupied by the two actors (aggressor and victim) in this dynamic, which does not occur in the present investigation. Another explanation is given for the lack of significant differences in the present analysis.

Menesini et al. (

2010) suggested that females, instead of highlighting importance to the position occupied by each of the siblings in their dyad, attach greater importance to the quality of the relationship established between them. Knowing that the sample of the present study consists mostly of female elements (59.8%), the position in the sibling dyad is expected to not acquire a prominent position. However, the existing literature does not corroborate the conceptions evidenced in the present study (

Finkelhor et al. 2006). Thus,

Finkelhor et al. (

2006), in a sample of 2030 children and adolescents aged between 2 and 17 years of age, could verify that older siblings attack more frequently when compared to the others. The same was found by

Tippett and Wolke (

2015), where they found an association between the perpetration of sibling aggression and being the eldest child.

As for the victimization of sibling violence, there were significant differences regarding physical assault compared to the position in the sibling dyad. The middle sibling, as victims, were more often involved in acts of physical assault when compared to the youngest or the oldest. It should be noted that the middle sibling is, according to the literature, the only one who does not have his role well defined in his phratry because the eldest is considered as the successor of the parents, while the youngest is the protected son, the one who is free from any responsibility (

Fernandes 2005;

Fernandes et al. 2007). It is thus suggested that, due to this condition, the middle sibling feels that his interaction with his parents is insufficient, considering that they do not give him the necessary attention. Thus, they are inherently aware of a sense of abandonment, guided by feelings of inferiority towards their siblings, which in turn leads to the presence of low levels of self-esteem (

Fernandes 2005), thus making them more vulnerable to the victimization of violent behaviors. Similar conclusions are described in the study by

Bowes et al. (

2014) with a sample of 2002 young adults aged 18 years. The authors found that victims of violence between siblings are characterized by belonging to a sibling dyad where an older brother is present. However, according to

Tippett and Wolke (

2015), the eldest siblings are also victims of sibling violence. The authors suggest that the youngest siblings desire the resources of the eldest siblings and, therefore, behave more aggressively.

The results of the present study also allow us to observe a predictive effect of self-esteem on the development of behaviors of both negotiation and sibling violence. This predictive effect is observed for both acts of perpetration and victimization, except for the victimization of sexual assaults; the existence of a positive role of self-esteem in negotiation behaviors is noteworthy. It is thus suggested, as already mentioned in the present discussion, that high self-esteem is associated with a greater capacity to resolve intra-family conflicts, thus favoring dialogue and communication between brothers and sisters. On the other hand, self-esteem is negatively associated with violent behaviors between siblings. In the face of such results, it seems that siblings who have high self-esteem, that is, who show high levels of satisfaction with themselves and the outside world, do not seem to have the need to develop any rivalry with any other sibling. Empirical conceptions present in the literature corroborate the results explained in that they argue that relationships between siblings influence self-esteem and a positive and healthy relationship between siblings benefits the quality of self-esteem, thus developing positive feelings and perceptions about oneself (

Yeh and Lempers 2004). Also, about the possible presence of aggressive behaviors in the dynamics between siblings,

Avanci et al. (

2007) and

Wiehe (

1997) show that elements with high self-esteem less frequently victimize aggressions perpetrated by their siblings. Concomitantly,

Wiehe (

1997) also postulates that in addition to the victims, aggressors in sibling violence are also characterized by low levels of self-esteem. Additionally,

Dantchev and Wolke (

2019) argue that high self-esteem seems to be protective of the victim status.

The position’s role in the sibling dyad was only significant for the perpetration of negotiation and psychological aggression and the victimization of psychological aggression and physical assault. In this follow-up, the middle brother reveals a greater predisposition to converse with the other siblings when compared to the youngest brother. It is suggested that this capacity for dialogue with others, present in the dyad, is because both the middle brother and the youngest one experience, from birth, social relations with the brothers. However, when these relationships are associated with the different fraternal roles that the middle brother can assume (

Fernandes 2005), they give him characteristics such as cooperation and negotiation. In addition to the relational networks experienced since its birth, it is also noted that this adaptability to situations gives them prosocial characteristics such as the capacity for dialogue. However, empirical conceptions present in the literature contradict the present result; according to

Fernandes (

2005) and

Fernandes et al. (

2007), the middle brother presents a personality marked by aggressiveness and little concern for others, focusing essentially on himself. Thus, the presence of capacities relative to the middle brother is not expected, such as the predisposition to establish conversations to resolve conflicts arising in the fraternal dyad. Also, when equated with the eldest, the middle brother reveals a greater involvement in behaviors of the perpetration of psychological aggression. The characteristics inherent to the older brother in the literature are suggested to assume special importance in this relationship. Especially in the case of being male, the eldest son is seen by the parents as their successor, the one who will continue with their legacy (

Fernandes 2005). Derived from this assumption, characteristics are inherent in the older brother that differentiate him from the middle brother. It is known that older people are revealed to be more conservative (

Fernandes 2005) to the extent that they are instilled, by their parents, with the values and beliefs adopted by them. For this reason, the older one presents personality characteristics such as integrity, responsibility, greater concern for others and lower aggressiveness (

Fernandes 2005;

Fernandes et al. 2007). Conversely, the middle brother is given characteristics such as competitiveness and aggressiveness (

Fernandes 2005;

Fernandes et al. 2007). However, the present results are inconsistent with the existing literature on this problem.

Finkelhor et al. (

2006), using a sample of 2030 individuals aged between 2 and 17 years, found that older siblings most often play the role of aggressor in sibling violence. The middle brother reveals being more the victim of psychological aggression than the older brother. Regarding being victims of physical assault, the middle sibling reveals greater involvement when compared to the youngest and oldest. These results align with those reported by

Dantchev and Wolke (

2019) where the firstborn children were more likely to be perpetrators. The results can also be explained based on the assumptions already evidenced in the current discussion. Knowing that characteristics such as low self-esteem (

Fernandes 2005) are found in the personality of the middle brother, this fact seems to predispose him to greater involvement in sibling violence (

Wiehe 1997), more specifically, assuming the role of victim. The same is no longer true for the other siblings (older brother and younger brother) because, as already mentioned, they are at the extremes of the fraternal constellation and have their fraternal roles very well defined, which gives them security (

Fernandes 2005), protecting them in situations demarcated by violence. These results point in the same direction as the empirical conceptions present in the literature, stating that high levels of self-esteem are inherent to a good relationship between siblings; on the contrary, in the face of a relationship demarcated by violence, it fosters the subject of a negative self-evaluation (

Yeh and Lempers 2004).

Finally, there was a sex role in the perpetration of sexual coercion and the victimization of injury, that is, of aggression causing serious physical harm. Thus, females, when compared to males, revealed a greater propensity to establish conversations and use this method to resolve conflicts arising within the sibling dyad. As already mentioned in the present discussion, it is suggested that, based on sex stereotypes, the adoption of negotiation behaviors by females was an expected result. Due to the belief that females should assume a behavior connoted by delicacy (

Simões et al. 2015), the primary attachment figures interact early with the baby according to these same convictions (

Seixas 2009). According to

Kindlon and Thompson (

2000), parents, in front of a female baby, maintain a longer conversation, always showing a concern for other individuals, which is no longer the case with a male child. In addition, the predisposition to a greater development of communicative skills also belongs to females (

Rubia 2007), as they achieve, before males, a maturation of social skills (

Legato 2009).

Regarding the perpetration of sexual assaults, compared to females, males stand out in the adoption of abusive conduct of this type. Sex stereotypes, as already mentioned in this discussion, once again seem to have a strong effect on this association. The behavioral mode, determined by a society that must be employed by males, is connoted by aggressiveness and frontality, contrasting with the subtlety and delicacy particular to females (

Simões et al. 2015). An inequality of power and a central characteristic of violence between siblings is also highlighted in this analysis. Noting that, normatively, males are physically stronger, the perpetration of sexual abuse is more achievable for them when compared to females (

Monks et al. 2009). The existing literature on the subject in question denotes evidence that follows the same direction as the results obtained in this study, clarifying the greater propensity of males to engage as aggressors in sexual violence when compared to the females (e.g.,

Relva et al. 2013;

Relva et al. 2014). Regarding the victimization caused by physical aggressions that cause serious physical harm, males also show greater involvement. It is suggested that these results can be explained by showing that males, recurrently, exert aggressions on individuals of the same sex (

Relva et al. 2014). In this sense, there are several studies that corroborate the results presented here, demonstrating that males have a greater propensity to be involved, as a victim, in behaviors of physical aggressions that cause serious physical damage (e.g.,

Relva et al. 2013;

Relva et al. 2014).

Practical Implications, Limitations and Suggestions for Future Studies

Regarding practical implications, the presence of high self-esteem levels in adolescents’ psychosocial development is highlighted, protecting them when they are in situations of sibling violence. This result is extremely important since self-esteem works as a protective factor. Additionally, developing programs that help children and adolescents improve the quality of sibling interaction can contribute to reducing sibling conflict. In this way, it is intended to highlight the importance of the adjusted development of self-esteem and alert to sibling violence. In addition, the sex of adolescents and the sibling position occupied seem to be relevant variables in the study of aggression between siblings. Teaching siblings to regulate emotions is also important to promote good sibling relationships. The current findings also suggest that siblings, where negotiation strategies are reduced, can be helped to develop these skills and contribute to reduced sibling violence. Parents can be taught to help children to acquire prosocial competencies.

The present study has several limitations. The first limitation is the cross-sectional character, not allowing the establishment of cause–effect relationships. The present investigation also uses self-report instruments. A convenience sample was also a limitation. Additionally, some participants presented a reluctance to answer the questionnaire regarding the problem of sibling violence since it is a theme that is still little accepted. Also, the small age range assumes great prominence, hindering the analyses of different ages. Finally, we only have the perspective of one sibling. Future studies should explore both perspectives and parents’ perceptions of the quality of the sibling relationships.

Expanding the sample to other age sets is suggested for future investigations to compare groups. Additionally, using longitudinal studies and covering other types of intrafamily violence to provide cause–effect connections.