Women and Leadership in Higher Education: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

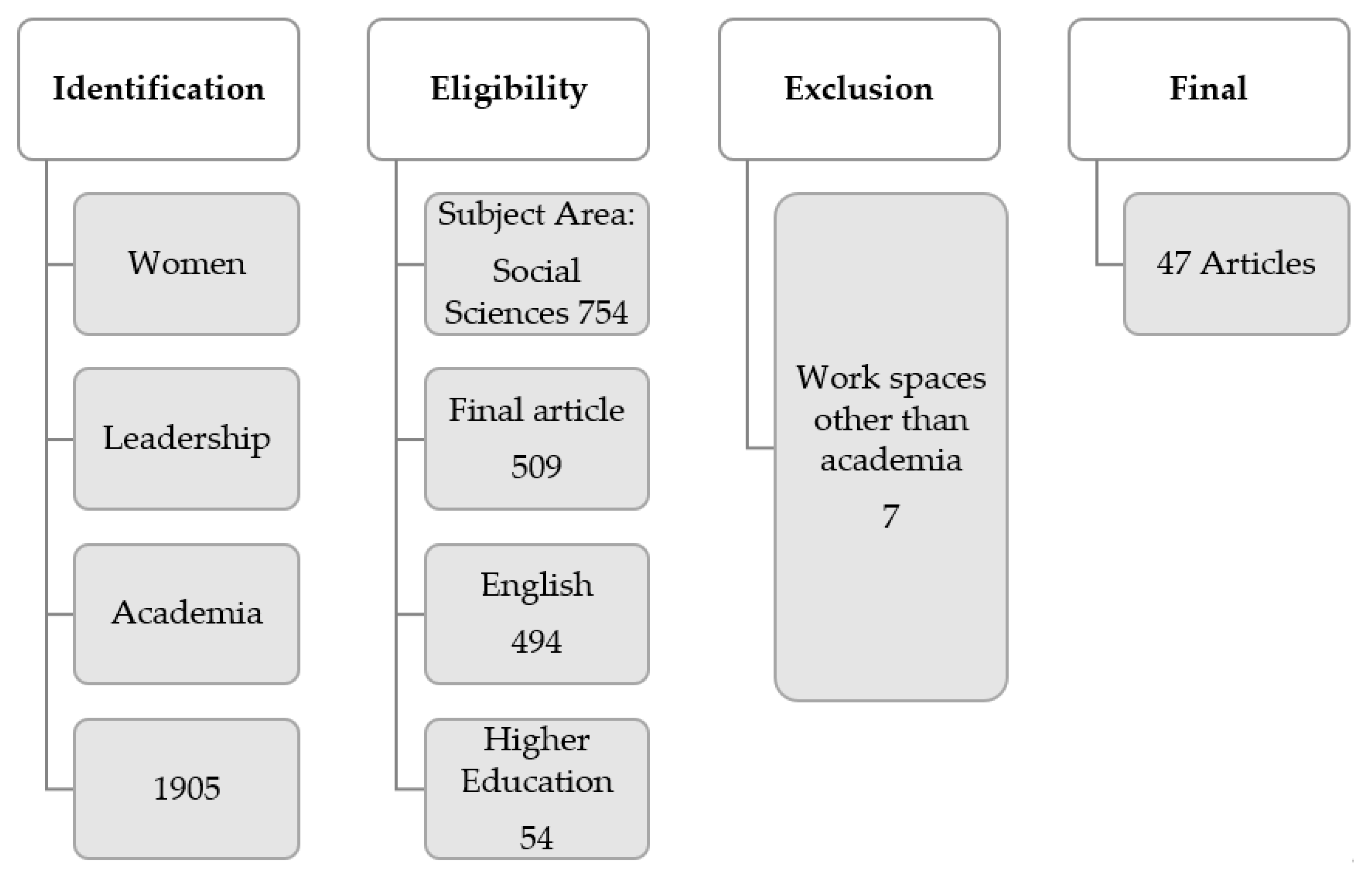

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

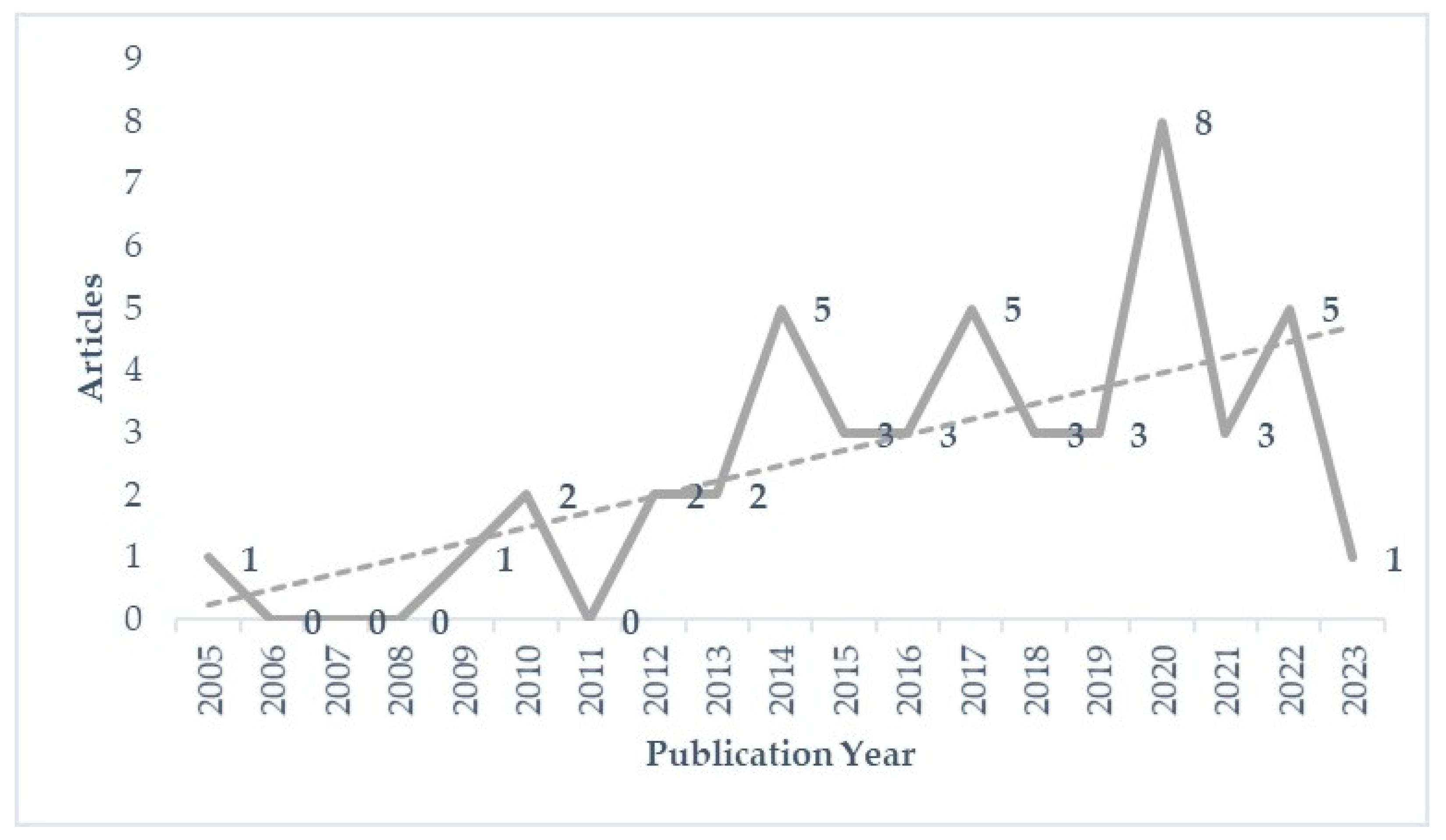

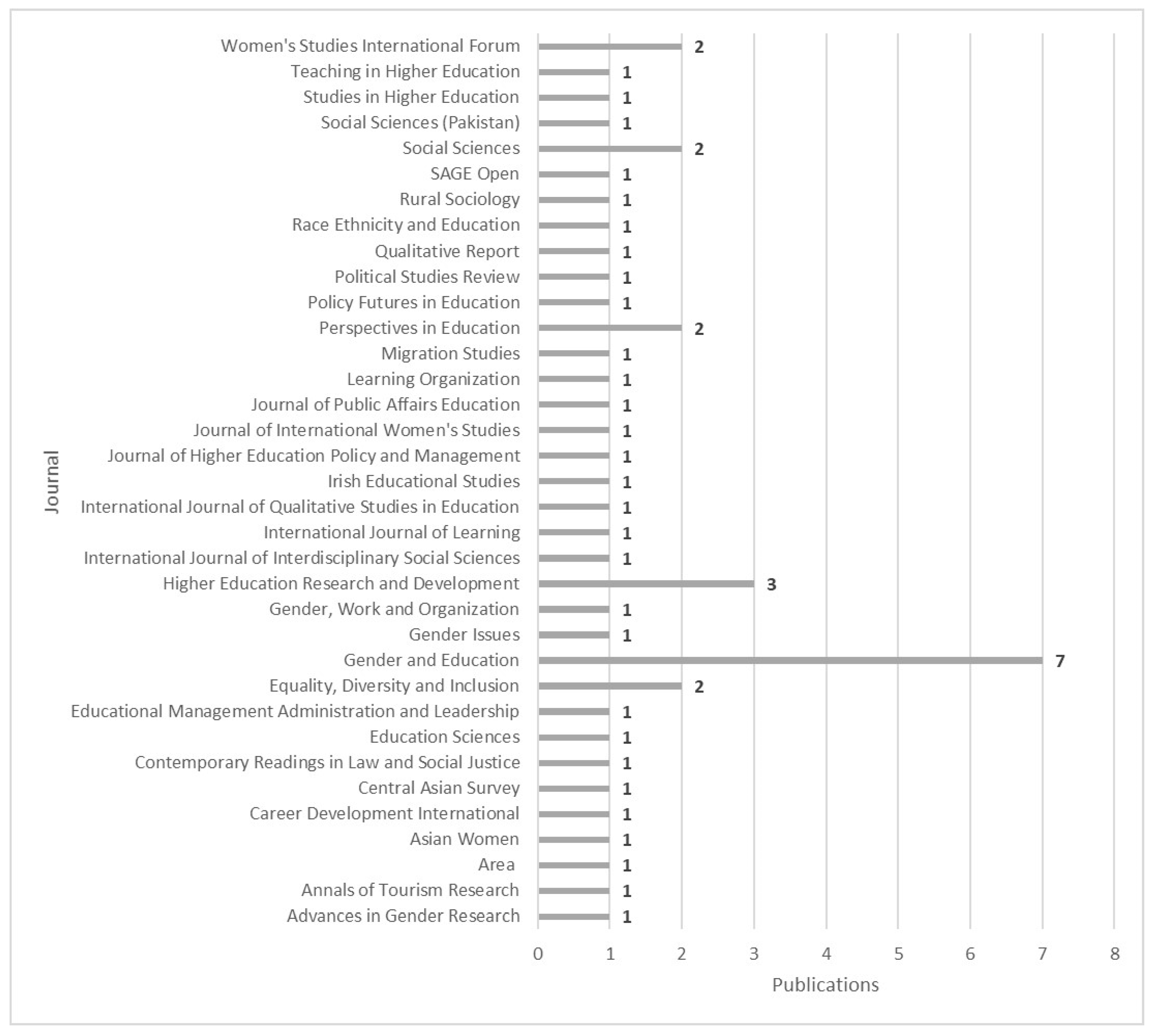

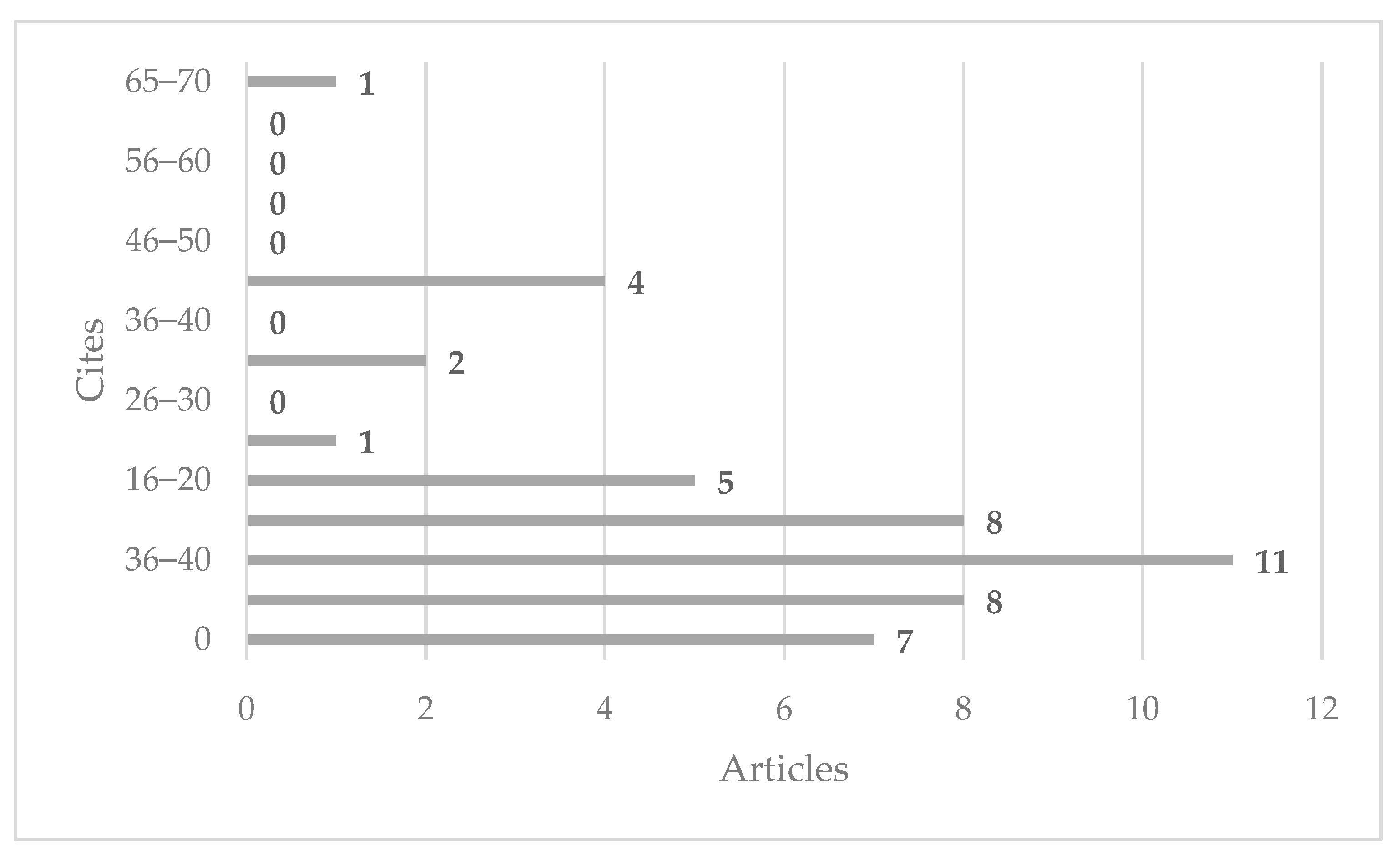

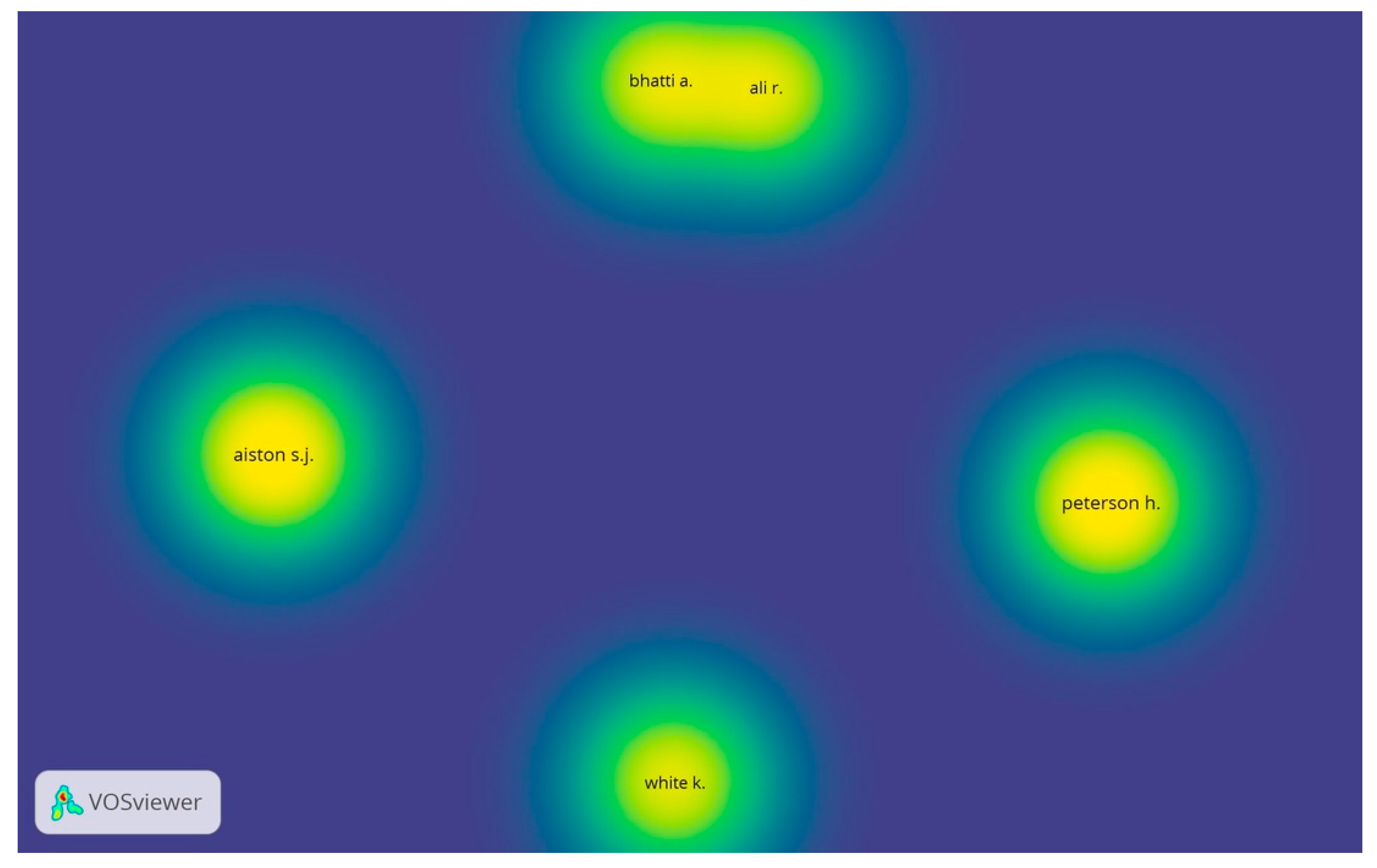

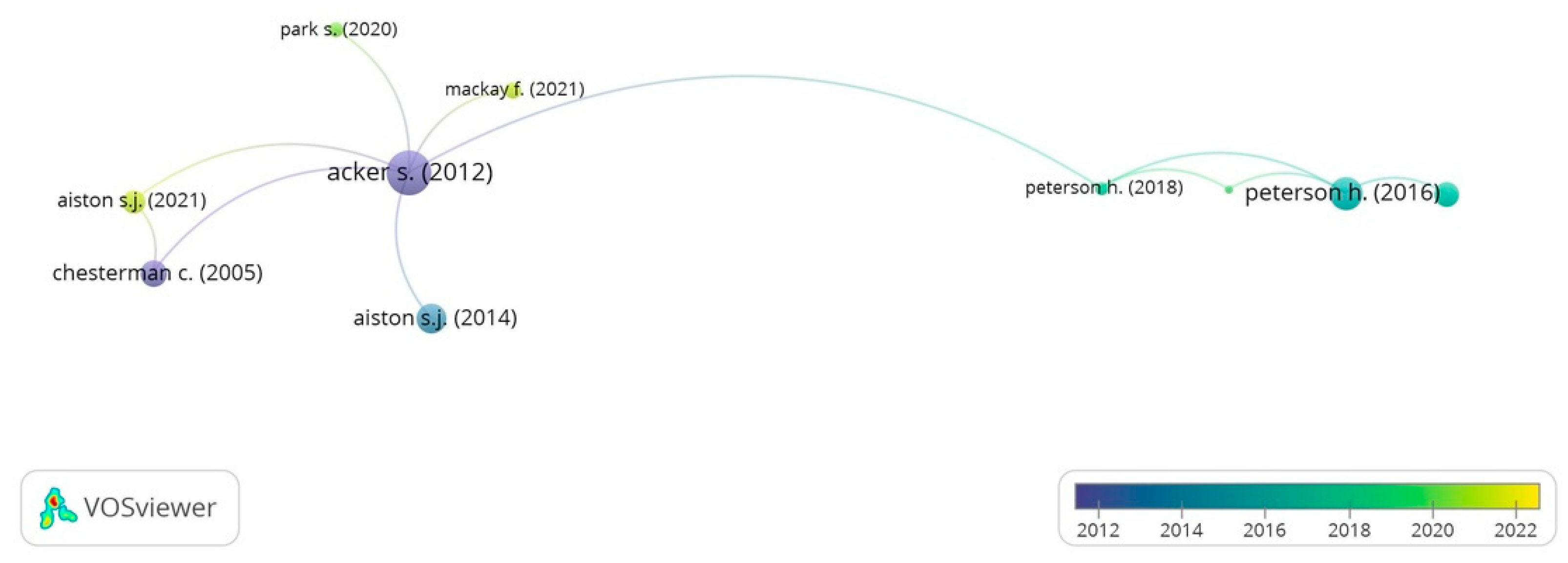

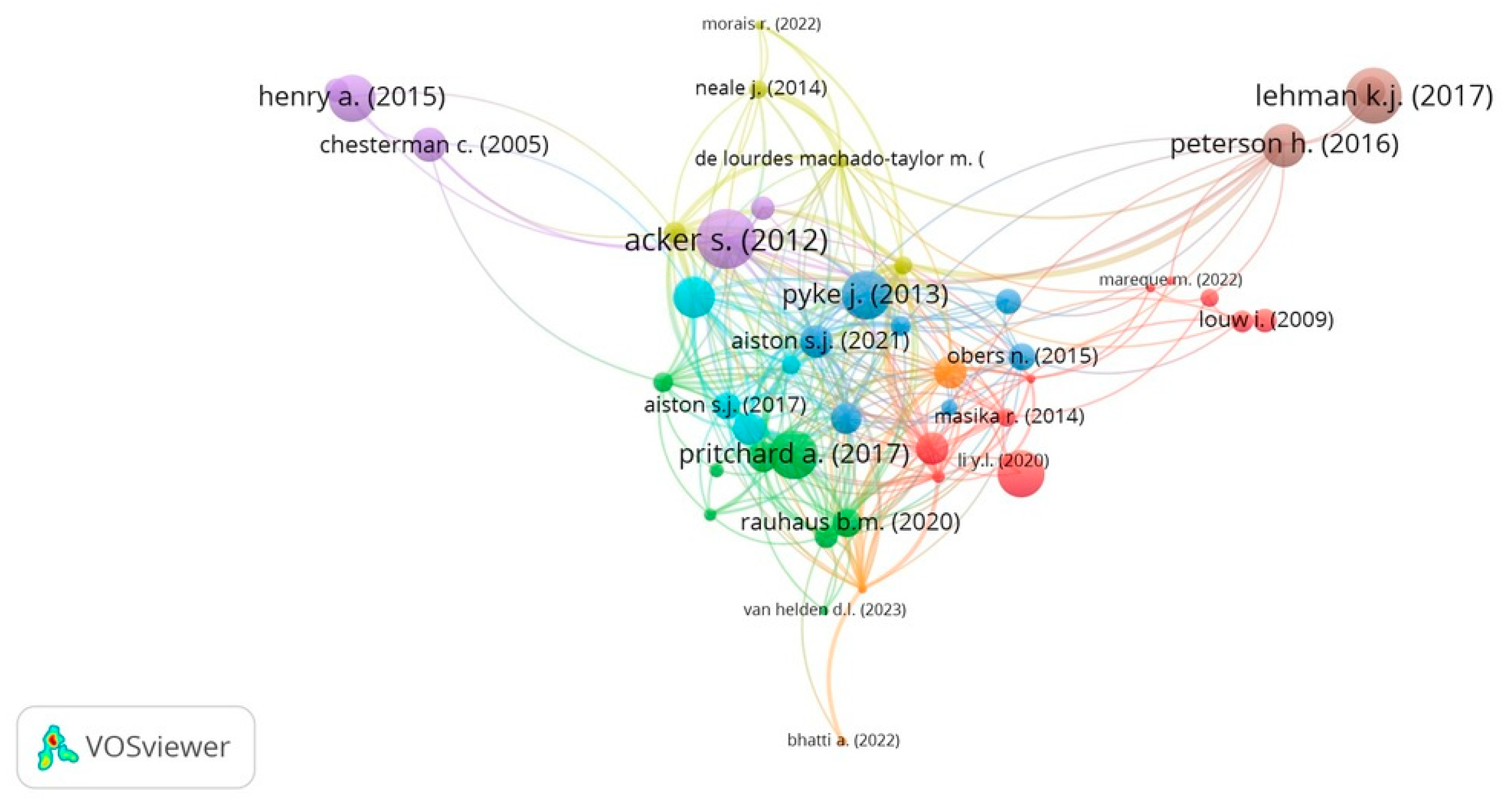

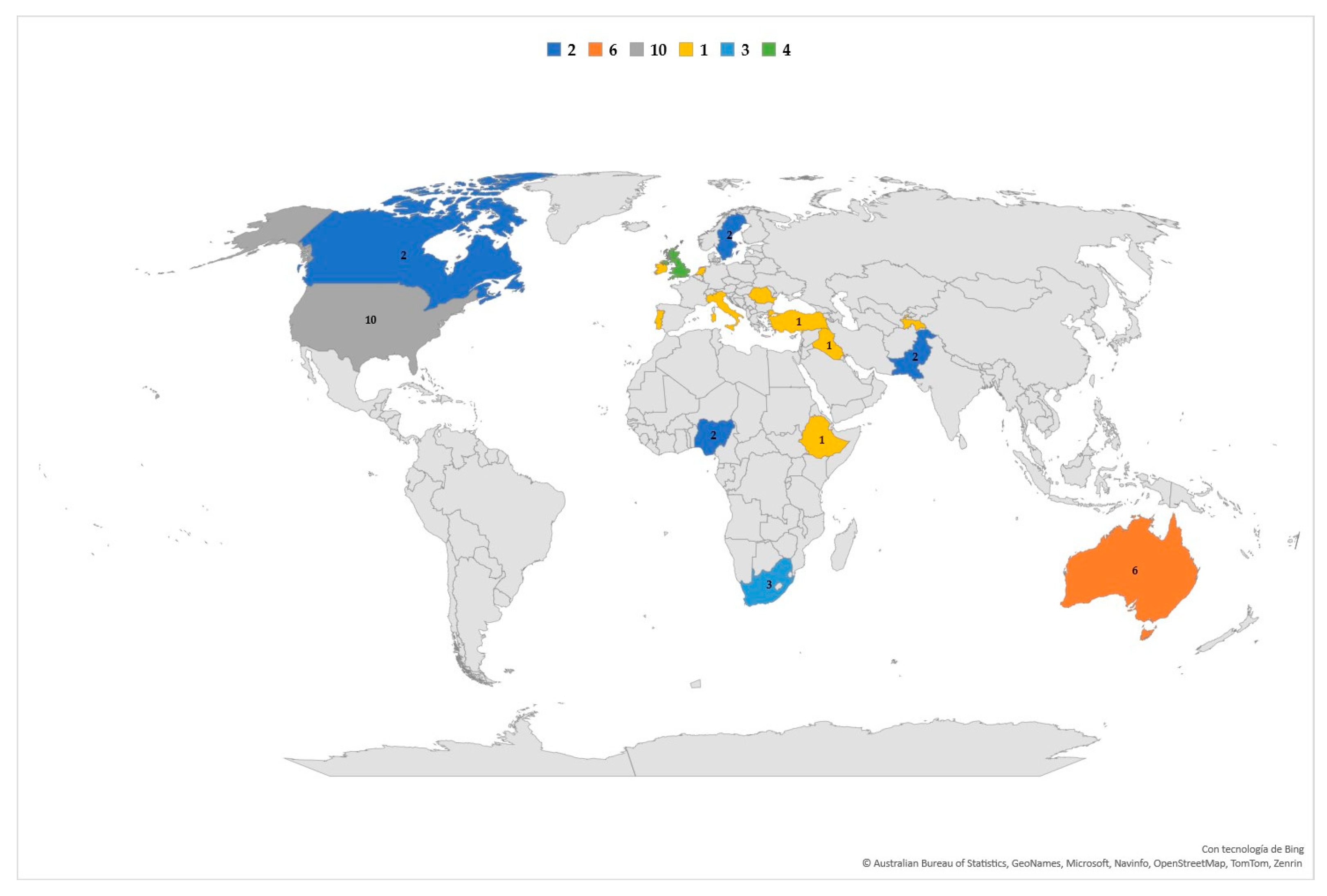

3. Bibliometric Analysis: Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Women’s Leadership in Academia

4.2. Women’s Leadership in Management

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acai, Anita, Lucy Mercer-Mapstone, and Rachel Guitman. 2022. Mind the (gender) gap: Engaging students as partners to promote gender equity in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education 27: 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, Sandra. 2012. Chairing and caring: Gendered dimensions of leadership in academe. Gender and Education 24: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiston, Sarah Jane. 2014. Leading the academy or being led? Hong Kong women academics. Higher Education Research & Development 3: 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiston, Sarah Jane, and Chee Kent Fo. 2021. The silence/ing of academic women. Gender and Education 33: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiston, Sarah Jane, and Zi Yang. 2017. “Absent data, absent women”: Gender and higher education leadership. Policy Futures in Education 15: 262–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, Traci. 2010. Roots of Leadership: Analysis of the Narratives from African American Women Leaders in Higher Education. The International Journal of Learning: Annual Review 17: 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaki, Samah, Abu Silong, Idris Khairuddin, and Wahat Nour. 2016. Understanding of the Meaning of Leadership from the Perspective of Muslim Women Academic Leaders. Journal of Educational and Social Research 6: 225–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Aisha, and Rabia Ali. 2021. Women’s Leadership Pathways in Higher Education: Role of Mentoring and Networking. Asian Women 37: 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Aisha, and Rabia Ali. 2022. Negotiating Sexual Harassment: Experiences of Women Academic Leaders in Pakistan. Journal of International Women’s Studies 23: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bilimoria, Diana, and Lynn Singer. 2019. Institutions Developing Excellence in Academic Leadership (IDEAL): A partnership to advance gender equity, diversity, and inclusion in academic STEM. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 38: 362–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabazon, Tara, and Samantha Schulz. 2020. Braving the bull: Women, mentoring and leadership in higher education. Gender and Education 32: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, Claudia, and Thomas DiPrete. 2006. The Growing Female Advantage in College Completion: The Role of Family Background and Academic Achievement. American Sociological Review 71: 515–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, Olga. 2012. Mujeres en la educación superior, la academia y la ciencia. Ciencia 63: 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chesterman, Collen, Anne Ross-Smith, and Margaret Peter. 2005. Not doable jobs!” Exploring senior women’s attitudes to academic leadership roles. Women’s Studies International Forum 28: 163–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Emily, Melissa Fuesting, and Amanda Diekman. 2016. Enhancing interest in science: Exemplars as cues to communal affordances of science. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 46: 641–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Julie, Emily Yarrow, and Jawad Syed. 2019. The curious under-representation of women impact case leaders: Can we disengender inequality regimes? Gender, Work & Organization 27: 129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPrete, Thomas, and Claudia Buchmann. 2013. The Rise of Women: The Growing Gender Gap in Education and What It Means for American Schools. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, pp. 1–24. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610448000 (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Donthu, Naveen, Satish Kumar, Debmalya Mukherjee, Nitesh Pandey, and Weng Marc Lim. 2021. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 133: 285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Jane. 2017. Narrating experiences of sexism in higher education: A critical feminist autoethnography to make meaning of the past, challenge the status quo and consider the future. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 30: 621–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekine, Adefunke. 2018. Women in Academic Arena: Struggles, Strategies and Personal Choices. Gender Issues 35: 318–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. 2018. Gender Statistics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Gender_statistics (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Gaete, Ricardo. 2018. Conciliación Trabajo-Familia y Responsabilidad Social Universitaria: Experiencias de Mujeres en cargos directivos en Universidades Chilenas. Docencia Universitaria 12: 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Morón, Nazareth, Mauricio Matus, and Lina Gálvez. 2020. Revisión sistemática de la literatura sobre el fenómeno del techo de cristal en las universidades españolas. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior 11: 130–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouthro, Patricia, Nancy Taber, and Amanda Brazil. 2018. Universities as inclusive learning organizations for women? Considering the role of women in faculty and leadership roles in academe The Learning Organization 25: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacifazlioglu, Ozge. 2010. Balance in academic leadership: Voices of women from Turkey and the United States of America (US). Perspectives in Education 28: 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hakiem, Raff. 2022. Advancement and subordination of women academics in Saudi Arabia’s higher education. Higher Education Research and Development 41: 1528–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harford, Judith. 2020. The path to professorship: Reflections from women professors in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies 39: 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgesen, Sally. 1995. The Female Advantage: Women’s Ways of Leadership. New York: Doubleday Currency. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Annette. 2015. ‘We especially welcome applications from members of visible minority groups’: Reflections on race, gender and life at three universities. Race Ethnicity and Education 18: 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, María, and Luz Ibarra. 2019. Conciliación de la vida familiar y laboral. Un reto para México. Iztapalapa. Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades 86: 159–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Lilian, and Celeste Wheat. 2017. The Influence of Mentorship and Role Models on University Women Leaders’ Career Paths to University Presidency. The Qualitative Report 22: 2090–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataeva, Zumrad, and Alan De Young. 2017. Gender and the academic profession in contemporary Tajikistan: Challenges and opportunities expressed by women who remain. Central Asian Survey 36: 247–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraz, Beatriz, José Pavía, and Luis Vila. 2019. Beyond the gender pay gap. Convergencia Revista de Ciencias Sociales 81: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Yun Ling. 2020. First-generation immigrant women faculty’s workplace experiences in the US universities—Examples from China and Taiwan. Migration Studies 8: 209–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, Cecilia, and Ortrun Zuber-Skeritt. 2009. Reflecting on a leadership development programme: A case study in South African higher education. Perspectives in Education 27: 237–46. [Google Scholar]

- Machado-Taylor, María de Lourdes, and Kate White. 2014. Women in Academic Leadership. In Gender Transformation in Academy, (Advances in Gender Research). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 19, pp. 375–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, Fiona. 2021. Dilemmas of an Academic Feminist as Manager in the Neoliberal Academy: Negotiating Institutional Authority, Oppositional Knowledge and Change. Political Studies Review 19: 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddrell, Avril, Kendra Strauss, Nicola Thomas, and Stephanie Wyse. 2016. Mind the gap: Gender disparities still to be addressed in UK Higher Education geography. Area 48: 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masika, Rachel, Gina Wisker, Lanja Dabbagh, Kawther Jameel Akreyi, Hediyeh Golmohamad, Lone Bendix, and Kristin Crawford. 2014. Female academics’ research capacities in the Kurdistan region of Iraq: Socio-cultural issues, personal factors and institutional practices. Gender and Education 26: 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, Mónica, Sara Galbán, and Claudia Ortega. 2019. Experiences and Challenges of Women Belonging to the Mexican National Researchers System. Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo 10: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-de-Luna, María Elena, Tania Conde, and Leticia Meza-de-Luna. 2022. Conciliación trabajo-familia con y sin niños y niñas, durante el confinamiento por COVID-19 en México. Psicoperspectivas 21: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncayo, Bibiana, and David Zuluaga. 2015. Liderazgo y género: Barreras de mujeres directivas en la academia. Pensamiento & Gestión 39: 142–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, Ricardo, Clara Fernandes, and Valeriano Piñeiro-Naval. 2022. Big Girls Don’t Cry: An Assessment of Research Units’ Leadership and Gender Distribution in Higher Education Institutions. Social Sciences 11: 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Ann, Randall White, and Ellen Van Velsor. 1987. Breaking the Glass Ceiling: Can Women Reach the Top of America’s Largest Corporations? Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Racusin, Corinne, John Dovidio, Victoria Brescoll, Mark Graham, and Jo Handelsman. 2012. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109: 16474–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, Jenny, and Kate White. 2014. Australasian university management, gender and life courses issues. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion 33: 384–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nett, Nadine, Tillmann Nett, Julia Englert, and Robert Gaschler. 2021. Think scientists—Think male: Science and leadership are still more strongly associated with men than with women in Germany. Journal of Applied Social Phycology 52: 643–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, Elvira. 2014. The importance of leadership development within higher education. Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice 5: 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, Nancy. 2017. Degrees of Difference: Women, Men, and the Value of Higher Education. New York: Routledge, pp. 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewoehner-Green, Jera, Mary Rodriguez Mary, and Summer McLain. 2022. The Gendered Spaces and Experiences of Female Faculty in Colleges of Agriculture. Rural Sociology 87: 427–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obers, Noëlle. 2015. Influential structures: Understanding the role of the head of department in relation to women academics’ research careers. Higher Education Research & Development 34: 1220–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oti, Adepeju Olaide. 2013. Social Predictors of Female Academics’ Career Growth and Leadership Position in South-West Nigerian Universities. SAGE Open 3: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew, McKenzie Joanne, Bossuyt Patrick, Boutron Isabelle, Hoffmann Tammy, and Mulrow Cynthia. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Sanghee. 2020. Seeking changes in ivory towers: The impact of gender quotas on female academics in higher education. Women’s Studies International Forum 79: 102346-1–102346-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Helen. 2016. Is managing academics “women’s work”? Exploring the glass cliff in higher education management. Educational Management Administration & Leadership 44: 112–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Helen. 2018. From “Goal-Orientated, Strong and Decisive Leader” to “Collaborative and Communicative Listener”. Gendered Shifts in Vice-Chancellor Ideals, 1990–2018. Education Sciences 8: 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Helen. 2019. Women-Only Leadership Development Program: Facilitating Access to Authority for Women in Swedish Higher Education? Social Sciences 8: 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, Annettea, and Nigel Morgan. 2017. Tourism’s lost leaders: Analysing gender and performance. Tourism’s lost leaders. Analysing Gender and Performance 63: 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privott, C. 2012. The Occupational Science of Women Faculty Work: A Qualitative Approach. International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences 6: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, Joanne. 2013. Women, choice and promotion or why women are still a minority in the professoriate. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 35: 444–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauhaus, Beth, and Isla Carr. 2020. The invisible challenges: Gender differences among public administration faculty. Journal of Public Affairs Education 26: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samudio, Edda. 2016. El acceso de las mujeres a la educación superior. La presencia femenina en la Universidad de Los Andes. Procesos Históricos 29: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sayler, Micheal, Smith Pedersen, and Marc Cutright. 2019. Hidden leaders: Results of the national study of associate deans. Studies in Higher Education 44: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semela, Tesfaye, Haile Hirut, and Rahel Abraham. 2020. Navigating the river Nile: The chronicle of female academics in Ethiopian higher education. Gender and Education 13: 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanò, Emanuela. 2020. Femina Academica: Women ‘confessing’ leadership in Higher Education. Gender and Education 32: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations [UN]. 2022. Objective 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. 2021. Women in Higher Education: Has the Female Advantage Put an End to Gender Inequalities? Paris: UNESCO, pp. 14–17. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377182 (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean [IESALC] and Times Higher Education. 2022. Gender Equality: How Global Universities Are Performing. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381739 (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Van Helden, Daphne, Laura Den, Steijn Bram, and Meike Vernooij. 2023. Career implications of career shocks through the lens of gender: The role of the academic career script. Career Development International 28: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Janice, and Dawn Wallin. 2015. ‘The voice inside herself’: Transforming gendered academic identities in educational administration. Gender and Education 27: 412–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuluaga, David. 2014. Perspectivas del liderazgo educativo: Mujeres académicas en la administración. Suma de Negocios 1: 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meza-Mejia, M.d.C.; Villarreal-García, M.A.; Ortega-Barba, C.F. Women and Leadership in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12100555

Meza-Mejia MdC, Villarreal-García MA, Ortega-Barba CF. Women and Leadership in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(10):555. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12100555

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeza-Mejia, Mónica del Carmen, Mónica Adriana Villarreal-García, and Claudia Fabiola Ortega-Barba. 2023. "Women and Leadership in Higher Education: A Systematic Review" Social Sciences 12, no. 10: 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12100555