1. Introduction

One major development in school education since the end of the 20th century has been the increasing importance of national and international tests (

Zajda and Majhanovich 2022). In a Western context, the first national tests and international tests were established in the mid-20th century, as tools for evaluation of school effectiveness and for enabling international comparisons of results. However, they did not have a prominent place in public debates about education or in pedagogical practice (

Lundahl and Tveit 2014). In contrast, in the 21st century, national and international tests are at the forefront of education policy, curricula, grading, and teaching (

Zajda and Majhanovich 2022). Large-scale tests have become an integrated part of school governance in national as well as international contexts. Studies have shown that such tests have a large impact on teachers’ selection of what content to teach and of pedagogical methods (

Au 2007,

2009). In the 21st century, international tests play a key role in guiding education policy on a global level (

Lundahl and Serder 2020). This holds true even in the Swedish context. The performance of Swedish students on international tests such as the PISA or the TIMSS test gives rise to great debate in Sweden and has led to the introduction of new educational policies, such as Matematiklyftet and Läslyftet

1 (

Carlbaum et al. 2019;

Österholm et al. 2016), and can be suspected, in part, also to have guided what is considered to be important knowledge in the different subject syllabuses. An increased emphasis on national tests as playing a role in students’ final grades suggests that the influence from international tests also trickles down to these national tests and as such affects pedagogical practice (

Wahlström 2009). Swedish national tests are designed to evaluate students’ knowledge and skills in relation to the knowledge and skills prescribed in the different subject syllabuses. The national tests can therefore be said to reinforce the steering of education towards goals prescribed in the subject syllabuses, and which knowledge and abilities students are given the opportunity to learn. The knowledge and abilities required in national tests, in combination with the curriculum, can be understood as setting a societal standard for the knowledge and abilities students are expected to master (

Forsberg and Lundahl 2006). Of course, the content of such a societal collective standard as expressed in national tests and curricula has always been at the forefront of political and ideological struggles regarding the purpose of school education (

Apple 1982;

Englund 1986). As such, a total consensus regarding the purpose of schooling will most likely never be reached in a democratic society (

Biesta 2021). One idea, however, in recent school debates about the curriculum has been that the main purpose of schools ought to be that students should be given the opportunity to develop powerful knowledge (PK) (

Young 2008;

Wheelahan 2012;

Muller and Young 2016).

The idea of PK developed from the discussions about realism within the sociology of education and a critique of the prominent relativism within the field (

Moore and Muller 1999). Since the 1970s, the social sciences in general have been characterized by a turn towards relativism and an increasing skepticism towards claims about objective knowledge (

Moore 2009). In the fields of sociology of education and curriculum theory, the knowledge prescribed by the curriculum has been criticized as representing the views of dominant social groups, an “official knowledge” (

Apple 1979) that represents a “knowledge of the powerful”. According to the critics of the traditional curriculum, the curriculum should instead highlight the experiences of disadvantaged groups, such as working-class students, women, and ethnic minorities (

Muller and Young 2019). It is this downplaying of knowledge in schools, and a highlighting of everyday experiences and generic competences in the curriculum and educational research, that has been criticized by

Young (

2008). He argues that even if we grant that knowledge is social and a part of societal struggles over knowledge, this does not preclude its objectivity, and that there is some knowledge that is better than other knowledge. Such powerful knowledge, because it is social, and produced in disciplinary communities following procedures to ensure its objectivity and validity (such as peer review), has better claims to truth than other forms of knowledge, and can therefore empower those who understand it to envision personal and societal alternatives (

Young 2008). Young argue that such knowledge is powerful, in that it enables students to see beyond their everyday experiences. Thus, according to social realists like Young, knowledge and abilities derived from academic disciplines should form the heart of the curriculum.

The knowledge emphasized in Swedish curricula has been thoroughly analyzed in previous research (

Sundberg 2021). In the light of the increasing importance given to national tests in Swedish schools described above, there seem to be a lack of research about which knowledge(s) in the syllabuses are in focus in national tests. There are some studies on international tests such as PISA and TIMSS in the Swedish context (

Englund 2018). As social studies, however, are not covered in these tests, there exists little research on large-scale tests in relation to the four social studies subjects (civics, geography, religion, and history). Previous research has characterized the 2011 religious education (RE) syllabus as being focused on academic disciplines in an international context (

Von Brömssen et al. 2020;

Jonsson 2016). As national tests are intended to measure the learning goals of the respective subject syllabuses, the RE 2017 national test seemed like a promising candidate to find aspects of PK in a social studies subject. Therefore, this article uses the theory of PK as a lens to examine the knowledge prescribed in the Swedish 2017 national test in RE for Grade 9. The focus of the present study is to explore whether and how powerful knowledge is manifested in items in the 2017 national test in religion. Our intention is to investigate the presence of PK in RE national test as an open question, and not to normatively judge the tests after PK criteria. To further investigate the aspects of powerful knowledge expressed by students, student answers that were awarded the grade A (the highest) were also analyzed.

3. Previous Research—RE in a Swedish Context and Powerful Knowledge

RE in Sweden has been an obligatory non-confessional subject in compulsory school since 1969, which makes it rather unique in an international context. The aim of RE is to give students knowledge about various religions, religious life-views, religious practices, history of religion, and existential questions about life and ethics (

Franck 2021b). However, before going into the history of Swedish RE in more detail, it is necessary to consider the relationship(s) between academic disciplines and school subjects, as this relationship is central to the PK theory. First, there is a distinction between school subjects and academic disciplines. For example, RE differs from religious studies as an academic discipline in content, history, and purpose. There is a dialectical relationship between school subjects and academic disciplines, but they are not and can never be the same, as the aims of school subjects differ from those of academic disciplines (

Stengel 1997). There is always a process of recontextualization between academic disciplines and school subjects, in which political and ideological struggles, as well as pedagogical considerations, shape the school curriculum (

Wheelahan 2012). As RE as a school subject, as stated above, includes content related to religious studies, religious history, and ethics, students’ development of PK in RE will be considered in relation the PK developed in these various academic disciplines.

Educational research has highlighted that school subjects are shaped by “selective traditions”, a dominant contextualization of a subject during a specific historical period that shapes the purpose, content, and teaching of a specific school subject in that period (

Englund 2004;

Knutsson 2011). Historically, Swedish RE was called Christianity, a confessional subject with a focus on promoting Lutheran Christianity. In the post-war period, it was re-named RE and was transformed into a non-confessional subject that emphasized objective fact. After a period of uncertainty regarding the purpose of RE during the 1970s 1980s and 1990s, this emphasis has been reintroduced in RE in the 21st century (

Jonsson and Månsson 2021).

Jonsson (

2016, pp. 70–76, 93–94) examined the curricula for compulsory and upper secondary school with a focus on the religion syllabuses 1962–2011. According to her, the curriculum of 1962 [Lgr62] was characterized by the view that education in knowledge about Christianity and other religions should be objective. The curriculum of 1969 (Lgr69) was also dominated by the view that teaching about religion should be objective, but with a larger emphasis on religions other than Christianity, and religious texts other than the Bible, and on the idea that the students should be more involved and could develop their own worldviews even though the school should remain objective. In the curriculum of 1980, RE was presented under a separate section in the integrated social studies syllabuses. A larger emphasis was put on existential questions, a student-centered perspective, and the experiences of immigrants in Sweden when comparing different religions traditions. Regarding the curriculum of 1994 [Lpo94], Jonsson highlights the absence of descriptions of obligatory content and an emphasis on existential perspectives in relation to personal development. In the revised religion syllabus of 2000 [Lpo94], existential questions, ethical analysis, and questions of differences and similarities between religions and cultural traditions were highlighted as central for the subject. In the 2011 syllabus [Lgr11] there was an increased emphasis on theory and religious studies as an academic subject, and a de-emphasis on students’ opinions and experiences in comparison with the syllabus of 1994 [Lpo94].

Von Brömssen et al. (

2020) compared religious literacy in the religion curricula for compulsory school in Austria, Scotland, and Sweden [2011, Lgr11]. They characterize the Austrian curriculum as humanistic, the Scottish as reconstructionist and moralistic, and the Swedish as an academic rationalist curriculum, with an emphasis on a scientific understanding of the world based on the academic discipline of religious studies.

Von Brömssen et al. (

2020) highlight that, of the three curricula, the Swedish RE syllabus appears as the one that is most directed towards knowledge and abilities derived from academic disciplines.

There is little research on RE from a PK perspective, as it is an emerging field within educational research (

Franck and Thalén 2023). Here, we highlight

Franck (

2021a) and

Osbeck (

2020) because they have studied Swedish RE from a PK perspective, and from them we derive some ideas about PK in Swedish RE.

Franck (

2021a) discusses subject-specific as well as subject-transcending issues relating to potential powerful knowledge in RE and raises critical points regarding the definitional process in which researchers, politicians, administrators, and teachers all make claims where “knowledge of the powerful” is at stake. He argues that teachers, regarded as subject experts, and academic experts in relevant fields such as religious studies, ethics, and philosophy must partake in curricular processes where conceptions of specific, disciplinary, and empowering knowledge are developed. Some potential candidates for constructive and useful second-order concepts are discussed and analyzed. The tentative conclusion is that there is an epistemological, narrative, conceptual platform which can be anchored in existing curricula for RE as powerful knowledge, but that it must be continuously analyzed and critically discussed in relation to contextual circumstances.

Osbeck (

2020) notices, with regard to ethics as a part of Swedish RE, that Young himself refers to a general ethical principle, namely Kant’s categorical imperative—“treat everyone as an end in themselves and not as a means to your end”—as an example of powerful knowledge, “because it is almost ‘a generalizable (or universal) principle for how human beings should treat others” (

Osbeck 2020, p. 7). With reference to a discussion on Young’s criteria for powerful knowledge,

Osbeck (

2020) opens the way for the possibility of identifying ethical knowledge as representing a complex moral discourse, with regard to which studies may contribute to the development of what can be defined as powerful knowledge. She remarks that “what becomes powerful is related to the context and the people present—even if different types of moral discourses are also traditionally associated with different amounts of power” (p. 8).

In our view, the RE syllabus in Lgr11 has many layers, resulting in a diversified mix of knowledge and abilities originating from the academic discipline of religious studies but also including general existential questions. Consequently, many different analytical tools can probably be fruitful in distinguishing how the differentiated syllabus is played out in the national test. However, in this study, we focus on using a lens of powerful knowledge to explore whether and how PK is manifested in items and student responses in the 2017 national test in religion. But before outlining the analytical framework of powerful knowledge used, first a short summary of the Swedish national test in religion is presented.

4. RE in Swedish National Tests

National tests have been a part of the Swedish compulsory school system for decades (

Skolverket 2005;

SOU 2016:25 2016). The tests are mandated by the Swedish government, via the National Agency for Education, and constructed by different Swedish university departments. For the purpose of reuse, the tests are normally confidential for some years after they have first been given. Traditionally, mandatory tests were only given in the 9th grade, i.e., the last year of compulsory school, in the subjects of Swedish, English, and mathematics (

Skolverket 2005;

SOU 2016:25 2016). Over the last few decades, however, the system of national tests has widened both with regards to when they are given, and which subjects are tested. Since 2013, an annual mandatory national test in RE is given. About 20,000 Swedish students, a quarter of all the 9th graders, take the test. The other three-quarters take the test in either civics, history, or geography. A random system, monitored by the National Agency of Education, decide which social studies subject the school and students receive. The schools and students are informed shortly before the examination. The intention of the test is mainly to support teachers in fair and equal grading (

SOU 2016:25 2016). As such, the test is closely related to the RE curriculum and could be viewed as

one contextualization of the curriculum (e.g.,

Skolverket 2017a,

2017b). The main principle for the design of the test has been to operationalize the curriculum in a test that can be completed by all students in Grade 9, regardless of which part of the country they come from, which school they attend, or which teacher they have. With regards to the curriculum of 2011 (

Skolverket 2019), the 9th grade students were to be evaluated and graded on how knowledgeable they were in relation to five overarching areas: (1) religious and non-religious worldviews, (2) the relationship between religions and society, (3) existential questions and identity, (4) ethical and moral concepts, models, and questions, and (5) collecting and evaluating information concerning religious and non-religious worldviews. Between 2013 and 2022, the RE tests were designed to encompass these five areas with between 2 and 12 items covering each area (e.g.,

Skolverket 2017a,

2017b). The items came mostly in two different formats: clustered close-ended items, such as thematic multiple-choice questions, and open-ended items demanding essay-like answers. In total, the test contained 22 to 24 such items with an approximately equal division between the formats. The 2017 RE national test analyzed in this study was constructed in relation to the 2011 RE syllabus (Lgr11), and not the currently used syllabus introduced in 2022 (Lgr22) that has replaced it.

5. Theoretical Framework: Social Realism and Powerful Knowledge in RE

Social realism as a theory was developed within the sociology of education and emphasizes the distinction between everyday knowledge and theoretical knowledge (

Moore 2013). Building on this distinction,

Young (

2008) argues that the overall purpose of schools is not to focus on students’ everyday experiences but to give them access to disciplinary knowledge derived from academic disciplines. The purpose of education is to give all students the opportunity to learn subject knowledge; to understand how this knowledge is produced and validated in different subjects; and to understand why this knowledge, albeit fallible and open to revision, is reliable and objective. According to

Young (

2008), such knowledge is powerful, in that it enables students to see beyond their everyday experiences, take part in society’s conversations, and envisage personal and societal alternatives. The following, based on

Chapman (

2021, p. 9) summarizes the dimensions of PK:

Distinct—in contrast to everyday common-sense knowledge derived from experience;

Systematic—the concepts of different disciplines are related to each other in ways that allow us to transcend individual cases by generalizing or developing interpretations;

Specialized—produced in disciplinary epistemic communities with distinct fields and/or foci of enquiry;

Objective and reliable—its objectivity arising from peer review and other procedural controls on subjectivity in knowledge production exercised in disciplinary communities.

Better claims to truth—than other knowledge claims relevant to the issues and problems it addresses;

The potential to empower those who know and understand it to act in and on the world, since they have access to knowledge with which to understand how relevant aspects of the world work and what the potential consequences are of different courses of action.

This knowledge is understood as powerful because it enables students to understand the world from universal principles that are applicable regardless of the local context and gives them tools to handle natural and social problems in an expedient way. The implication for education is that the main purpose of schooling ought to be to give students access to this kind of knowledge. Students should learn subject knowledge as well as disciplinary knowledge (i.e., knowledge that involves an understanding of the basis for its own validity). Of course, almost all curriculum theorists would agree that school curricula should include both subject knowledge and disciplinary knowledge but differ regarding opinions on what kind of knowledge should provide the foundation of the curriculum. Traditionalists (e.g.,

Hirsch 1988) value subject knowledge as most important, whereas social constructivists place an emphasis on procedural aspects and generic abilities (such as problem solving) (e.g.,

Usher and Edwards 1994), and social realists emphasize both subject knowledge and the abilities that are entailed in disciplinary knowledge. The disciplinary aspect of knowledge is seen as critical from a social-realist perspective: that schools should give students the opportunity to learn subject-specific methodological and procedural abilities in relation to how knowledge is produced and validated in each discipline. Further, schools should introduce and have a focus on abstract theoretical knowledge rather than students’ everyday experiences.

For the purpose of analysis, we focus on the

knowledge and

abilities emphasized in the RE national test. We choose these categories because they include both subject knowledge and the abilities entailed in disciplinary knowledge. More specifically, considering the content of Swedish RE, we focus on PK in relation to religious studies, religious history (

Franck 2021a), and ethics (

Osbeck 2020). According to

Franck (

2021a), RE should have a focus on theoretical knowledge (such as about religions, religious history, and religious texts) that goes beyond simple facts and how religious beliefs are expressed in people’s lives. Drawing from RE as a field of research, he highlights “threshold concepts” as gateways for students’ development of new knowledge with a focus on knowledge about religion and a “know-how” that can enable students to relate to how religion is expressed in theory and practice. Though Franck does not elaborate in detail what abilities could be central for PK in RE, drawing from his general outline, we consider two plausible candidates to be the ability to make comparisons of religions and the ability to critically interpret religious texts (source criticism).

Osbeck (

2020), as mentioned above in relation to ethics education in Swedish RE, stresses knowledge and understanding of general ethical principles as an example of PK in RE. Drawing from Franck and Osbeck, we present examples of knowledge and abilities that could be seen as PK in Swedish RE. In

Table 1, we give some examples of PK in RE, which are put in contrast to examples of content in RE which we do not consider to be PK. These examples do not present a coherent theory about PK in relation to Swedish RE, as it is an emerging field, and no such theory currently exists (

Franck and Thalén 2023). However, the examples are drawn from previous research about PK in RE. These examples provide focus points and are the basis for the analysis of the 2017 RE national test.

6. Methods

As noted in the introduction above, the Swedish national test in RE is given in the 9th grade. It is held every year in the spring term in April or May. The national tests are normally confidential, but after five years they are made public. In the analysis, we use the test conducted in 2017, as this is the last test that has been made publicly available. The test consists of two different item-formats. The 2017 test had 12 closed-ended items such as clustered multiple-choice questions, and 11 open-ended items demanding essay-like answers. In total, the test consisted of 23 items (see

Appendix A). In the first part of the analysis, the open-ended items in the test of year 2017 were analyzed, targeting whether qualities of powerful knowledge could be found in the items. Each item was analyzed separately, starting from the beginning of the test. In this approach, we were led by the operational indicators presented in

Table 1 in the theoretical section above. As the indicators in

Table 1, examples of PK and not PK, are outlined as outer ends of a continuum, the analysis was first and foremost focused on trying to distinguish those items that clearly require powerful knowledge. However, we also tried to identify examples of items not relating to aspects of powerful knowledge. In the qualitative content analysis, items were illuminated by distinguishing whether they included, for example, instructions about

describing certain religions/or ethical principles, and comparing these religions/ethical principles, versus items relating to

personal and/or general outlooks of life, and reasoning about such in terms of personal faith perspectives. Consequently, the underlying assumption in distinguishing items in this regard was that certain items, to some extent, probably had potential for facilitating the use of PK that other items did not. However, to validate this assumption, we included a second step in the analysis.

For the second step of the analysis, focus was on investigating whether PK was identified in students’ answers to the selected items. For this purpose, we used the database of student answers for the Swedish national tests. For the RE test, and each item in the test, approximately 600 students’ answers (students born on the 6th of each month) are copied and sent to the department of Pedagogical, Curricular and Professional Studies at the University of Gothenburg. As the system is based on a random selection of students’ answers in about 200 schools, the data can be argued to constitute a cross section of Swedish students’ answers to the 2017 national test in RE. Consequently, access to the students’ answer database provides the opportunity to analyze students’ answers to items. A total of 15 percent of the student tests in the database—90 student tests—were randomly selected. Of the 90, we picked out all student tests graded A, the highest possible grade, in total 9 tests. The argument for this demarcation is, of course, that focusing on A-graded tests when reviewing the student responses to items gives us the greatest probability of finding traces of PK in the answers. The student answers were analyzed using qualitative content analysis, with the overarching purpose of identifying possible aspects of PK in the students’ answers to the items selected in the first step of the analysis. The theoretical concepts presented in

Table 1 are used as focus points for the analysis in highlighting different aspects of PK in RE.

The analyses of each student answer to each item were focused on illuminating whether, and if so in which way, traces of powerful knowledge—subject-specific knowledge and methodological and procedural skills—were used in the students’ responses to the items. The focus of the analysis was to investigate whether the students’ answers to items included powerful knowledge as defined in the theoretical framework. An advantage of a content analysis is that it allows for long descriptions of empirical materials; in this article, selections of questions in national tests are given in detail and student answers are transcribed in full (

Boréus and Bergström 2017).

7. Results

The results are presented through the analysis targeting whether and how PK is manifested in the 2017 Swedish RE national test items. We present the results by analyzing opened-ended items that relate to aspects of PK in RE described in the theory section above, followed in each case by an analysis of a student answer to the item. Lastly, one item and a student answer to this item that do not entail aspects of PK are analyzed. All student answers have been translated from Swedish by the authors. The items discussed are presented in their entirety in

Appendix A.

7.1. Comparisons of Religions: Hinduism vs. Another Religion

The ability to make comparisons between religions depends on both subject knowledge and disciplinary knowledge and can, as mentioned above, be seen as an example of PK in RE. One could argue that the ability to make such comparisons is essential for answering Item 7. The instructions for Item 7 are as follows: “Discuss two similarities and two differences regarding the view of god between Hinduism and another religion of your choice”. As may be seen, four parts in the sentence are in bold. Further, the item includes an additional sentence instructing the students to: “Make the similarities and differences clear with examples and explanations”. Last, there is a framed rectangle with an initial bold text instructing the students to, “Use the following questions to help you”, followed by four questions, “Is there one god/several gods? What characteristics does the god(s) have? How do you contact the god(s)? How is the god(s) noticeable in people’s lives?”. Beside the instructions, there is a picture of the Hindu god, Shiva.

Reviewing this item through the lens of powerful knowledge, we think it is fair to argue that it includes instructions asking for certain specificities of Hinduism, and another religion of the student’s choice. Consequently, it demands knowledge about religion, i.e., key principles and probably some historical pointers, relevant to use in constructing an answer. The item also enables the student to discern similarities and differences between Hinduism and another religion; thus, it includes instructions applying the ability for comparison of the two entities. The information in the framed rectangle can be seen as a help for starting this comparison. Looking at a student answer to this question, it becomes clear that the item requires a student to express aspects that can be viewed as powerful knowledge.

Item 7, student answer

One similarity between Hinduism and Christianity is that the god(s) are omnipotent. For example, in Christianity the god has created the world, and, for example, the elephant god Ganesh can make sure that you do well at school. Another similarity is that contact with the god(s) is better in places of worship, temples in Hinduism and churches in Christianity. For example, many Hindus visit temples to offer food and other things to the gods and many Christians go to church to pray. One difference between Hinduism and Christianity is that in Hinduism there are several gods with different powers and knowledge, but in Christianity there is only one with all the powers you might need. For example, the different temples are assigned to a specific god, so if you want help with a certain thing, you go and sacrifice and pray in one temple, and for another issue to a god in another temple. In Christianity, you can pray to God for any kind of help anywhere, although contact with God is stronger in churches. Another difference is that in Christianity the god does not have a direct form or body, but in Hinduism the gods have different bodies and look different. For example, the elephant god Ganesh has an elephant head.

As noted, the student starts off by giving examples of two similarities between the religions, Hinduism and Christianity: the unlimited power of god/gods (using the rather explicit concept of omnipotence) and the use of temples/churches to worship god/gods. When discussing differences, the student focuses on polytheism versus monotheism, also returning to the connection between temples and gods in Hinduism and ends with the embodiment of the Hindu gods. Consequently, the student uses the possibilities given in the item to demonstrate her/his knowledge about religions and compare religions and religious practices. The student answer thus entails both subject knowledge and “know-how” to apply that knowledge, which according to

Franck (

2021a) could be seen as essential for PK in RE.

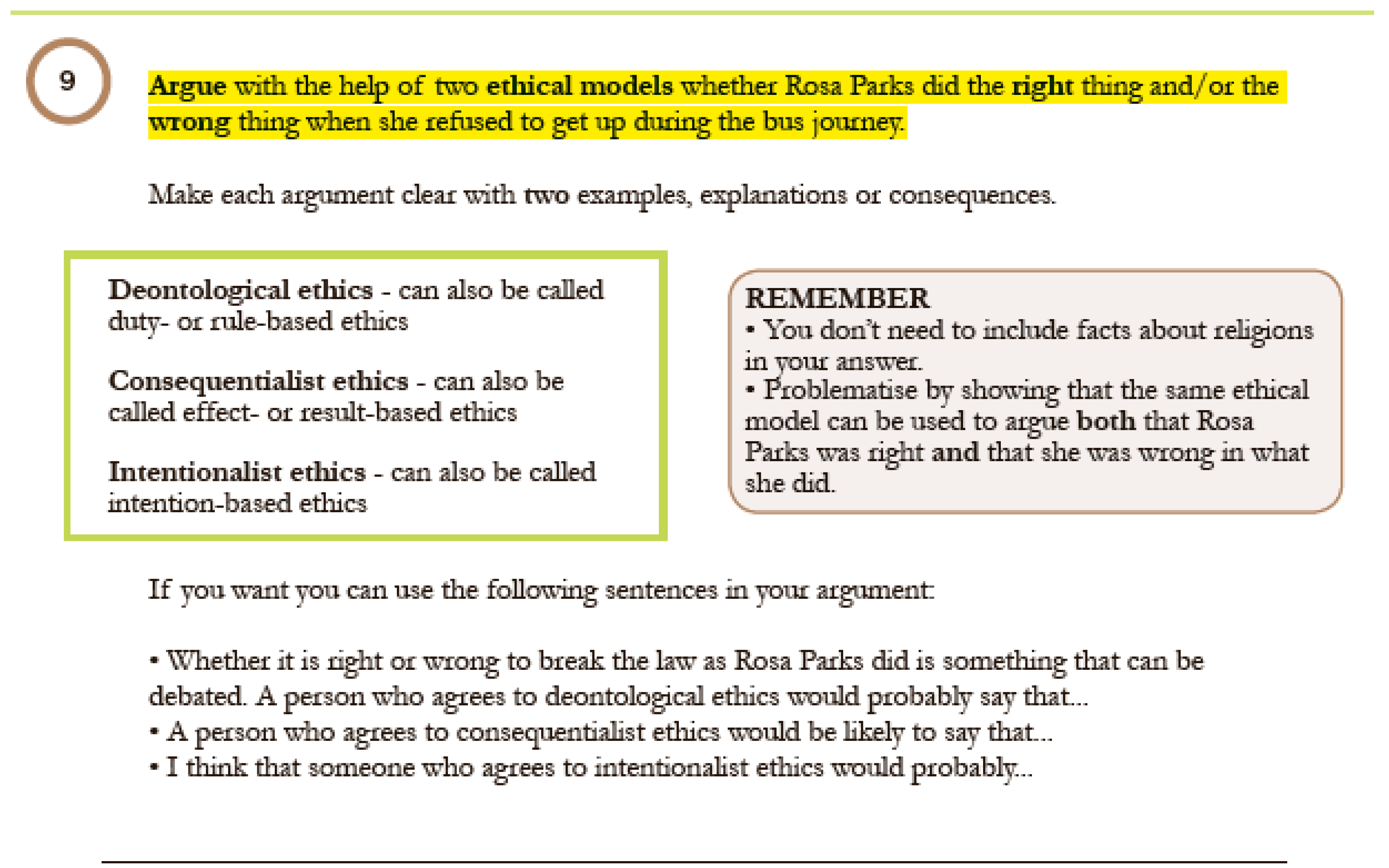

7.2. Ethical Principles: The Action Taken by Rosa Parks

Understanding universal ethical principles and how they can be applied to many different social and historical contexts, which go beyond the lived experiences of students, can as mentioned above be seen as a central aspect of PK in Swedish RE (

Osbeck 2020). We suggest that such an understanding is essential to answering Item 9. In the instructions for Item 9, the students were asked to read a text about Rosa Parks and then answer questions (see the text in

Appendix A). The text was accompanied by a picture of Rosa Parks and the Cleveland Avenue bus. In the instructions, students were asked to: “

Argue with the help of two

ethical models whether Rosa Parks did the

right thing and/or the

wrong thing when she refused to get up during the bus journey”, and further to, “Make each argument clear with

two examples, explanations or consequences”. As with Item 7, certain words are highlighted using bold text. The students were also briefly informed about the ethical theories in the following way: “

Deontological ethics—can also be called duty- or rule-based ethics;

Consequentialist ethics—can also be called effect- or result-based ethics;

Intentionalist ethics—can also be called intention-based ethics”, supported by reminders that “you don’t need to include facts about religions in your answer”, and to “problematize by showing that the same ethical model can be used to argue

both that Rosa Parks was right

and that she was wrong in what she did”. The instructions ended with: “If you want, you can use the following sentences in your argument: Whether it is right or wrong to break the law as Rosa Parks did is something that can be debated. A person who agrees to deontological ethics would probably say that..., A person who agrees to consequentialist ethics would be likely to say that..., I think that someone who agrees to intentionalist ethics would probably...”.

Through a lens of powerful knowledge, it is obvious that the key principles of the ethical models are presented to be discussed in this specific moral incident of a personal and societal nature, which is of great historical importance. In this way, the item enables the students to show both explicit knowledge, of at least two of the ethical principles (to understand and explain them), as well as the ability to apply them (in terms of comparing and seeing consequences). Let’s look at a student answer that indicates the potential of the item to encourage the expression of aspects of powerful knowledge.

Item 9, student answer

A deontological ethicist would probably suggest that what Rosa Parks did was wrong because she broke the laws that society has established and that they should therefore be followed in order to keep society as peaceful and law-abiding as possible. However, a deontological ethicist could also think that it was right because all people are of equal value and therefore some people should not be treated differently because of their skin colour or something like that, hence it was right because human rights are a law that should be followed. A consequentialist would say that Rosa Parks did the right thing because she protested for a human right and as a result society and the law changed for the better even though she had to break a law. But they could also think that it was wrong because there were huge protests, which created unrest in society and therefore she should have accepted the situation and stood up to keep the peace.

In the answer, the student begins by discussing Rosa Park’s actions from the perspective of deontological ethics. The student here shows a basic understanding of deontological ethics by stating that it is possible to come to different conclusions about Rosa Park’s actions depending on which duty or rule one starts from. When the student does this, he/she also show that he/she can apply deontological ethics to an individual case, i.e., the example of Rosa Parks. A few sentences down, the student changes perspective and discusses Rosa Park’s actions using consequentialism. In the same way as with deontological ethics, the student here manifests a basic understanding of consequentialism by drawing attention to various consequences (both positive and negative) of Rosa Park’s actions. Just as with the deontological ethics, this also means that the student shows an ability to apply consequentialism to an individual case. Overall, it could thus be argued the student shows an “multidimensional ethical competence”, which according to

Osbeck (

2020) could be seen as a central aspect of PK in Swedish RE.

7.3. Subject Knowledge about Religions: The Five Pillars of Islam

According to

Franck (

2021a), drawing his argument from

Young (

2008), subject knowledge can be seen as a fundamental aspect of PK in RE. One could argue that Item 19 is a question with a focus on subject knowledge. This item shows a picture of the five pillars of Islam. On each pillar, descriptions are written: “profession of faith”, “prayer”, “charity”, fasting”, and “pilgrimage”. In the text that follows, the picture is explained, “The five pillars above are important for all believing Muslims. Prayer is one of the five pillars within Islam”. Then students, in the first part (A), are to read four sentences and finish them. “

Describe how prayer is performed in Islam by finishing the sentences below: When you pray you turn towards the city of…, Before you pray, it is important that you (give one example)…, The day of the week that it is most important to go to the mosque and pray is…, During the service in the mosque, the prayer is led by…,”. In part B of the item, the students are to write an answer to the question “Choose

three of the five pillars of Islam on the previous page. Explain

why these

three actions are carried out.” Lastly, in part C, students are instructed to “Point out

similarities between why

three of the actions are carried out (The actions don’t need to be the same as in part B)”.

Compared to Item 9, Item 19 can be argued to focus explicitly on knowledge. To give a satisfactory answer, a student must have a solid understanding of the religion of Islam, i.e., why certain things are of importance for believing Muslims and how some of these things are related to one another. However, maybe it is fair to say that a devout Muslim, or a student brought up in an Islamic culture would not consider this particularly powerful knowledge to possess. Nevertheless, since Sweden is a very secular country, with a vast majority of non-Muslims, having this kind of knowledge can be regarded as far beyond the everyday experiences of religion for a 15-year-old. Let us look at a student answer.

Item 19, student answer

- (A)

Mecca, taking off shoes, Friday, Imam

- (B)

Fasting is carried out partly to remind people of the plight of the poor, and partly because it was historically so. Almsgiving involves giving money once a year to the poor people or those worse off. The profession of faith, witnessing your faith to God, shows that you are a believer through prayer.

- (C)

Both the profession, the prayer, and pilgrimage show that you are following the will of Allah. The Koran states that you should make a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in your life and you pray and confess to God, which is also written in the Koran, how to pray and behave. You follow the will of God!

As may be seen in the student’s answer, the instructions give her/him the opportunity to explicitly consolidate knowledge about the religion of Islam. It further enables the student to describe why the actions based on the principles in the pillars are carried out. In this way, the item, and the A–C instructions, give the student the opportunity to show her/his knowledge about religion (in this case Islam) and how the principles are applicable for a believing Muslim. In other words, there is room in the item for the student to manifest PK.

Franck (

2021a) elucidates that from a PK perspective, RE needs a “knowledge base”, even though this base is a temporary common societal standard in a specific socio-historical context that is open to revision. The subject knowledge in focus in Item 19 could be understood as part of such a standard in relation to RE.

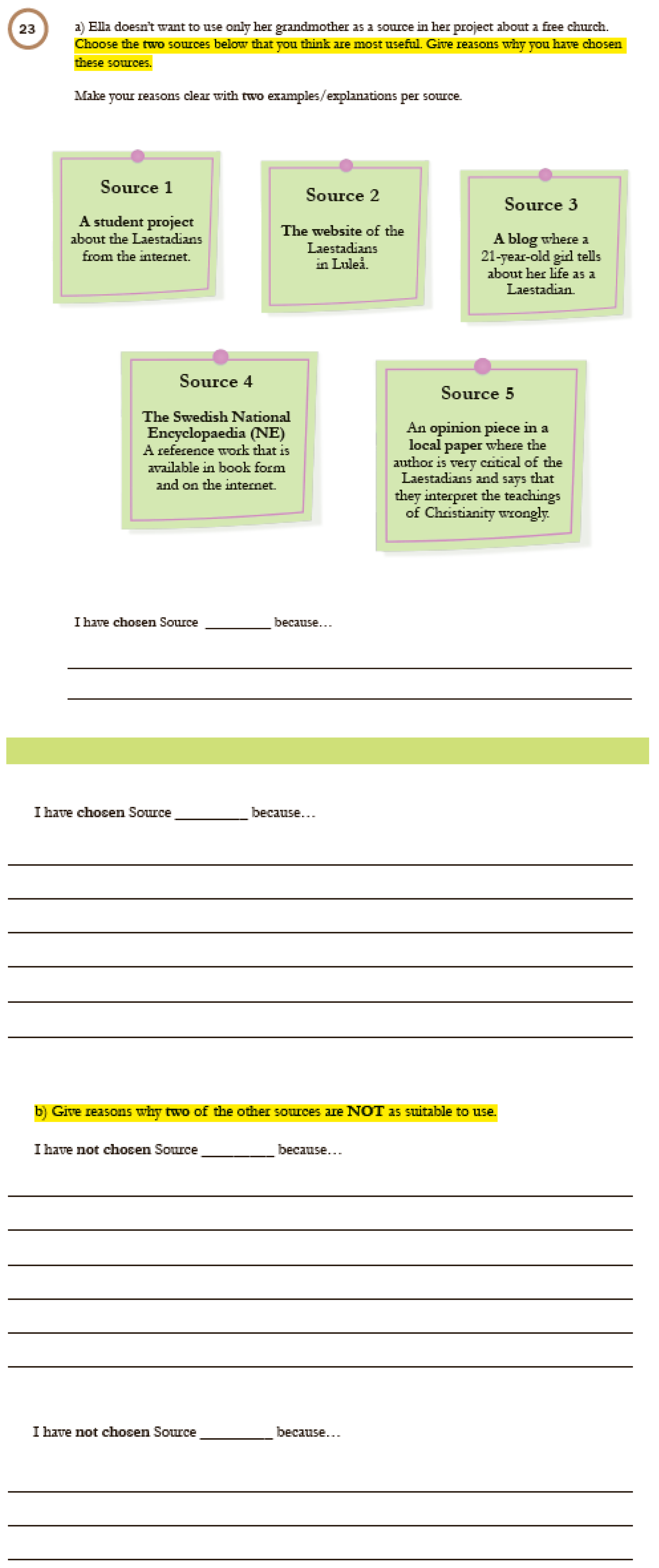

7.4. Source Criticism: A School Project about a Free Church

Disciplinary knowledge entails, as explained above, both subject knowledge and an understanding of how that knowledge is produced and validated in academic disciplines (

Young 2008). Item 23 has a focus, from a PK perspective, that relates to such methodological and procedural abilities, in this case source criticism rather than subject knowledge. The initial text in the item is about a girl named Ella and her Laestadian grandmother. Ella has been given the task of doing a project about a Swedish free church, the Laestadian church. The instructions following the text state that “Ella doesn’t want to use only her grandmother as a source in her project about a free church.” Then the student is asked to “Choose the

two sources below that you think are most useful”, and further to “Give reasons why you have chosen these sources”, and “make your reasons clear with

two examples/explanations per source.” The sources presented are: “(1)

A student project about the Laestadians from the internet. (2)

The website of the Laestadians in Luleå. (3)

A blog where a 21-year-old girl writes about her life as a Laestadian. (4)

The Swedish National Encyclopaedia (NE). A reference work that is available in book form and on the internet. (5) An

opinion piece in a local paper where the author is very critical of the Laestadians and says that they interpret the teachings of Christianity wrongly.” The students were then to argue which two sources they would choose to use for the project and which two were not suitable to use.

In the instructions for the item, the students are required to engage in source criticism in order to understand the Laestadian religious practice. The main task is to distinguish which of the sources presented are most valid, given the instructions, and which are not, and to understand the possible biases of each source. Arguably the item requires methodological and procedural abilities, but maybe not with subject-specific (religious) knowledge at the forefront. However, the Laestadian church is the topic of the imaginary project, and the choice of sources should be made by the students from this point of departure. Nevertheless, there is reason to assume that students can make an argument based upon everyday experiences of source criticism, even though that is not an ideal answer from a PK perspective, rather than specific knowledge, so let us take a look at a student answer.

Item 23, student answer.

I have chosen Source 4 because: Everything that is published on NE is written by people who have a really good grasp of the subject, and you know that what is published there has been checked very carefully to avoid incorrect information being published.

I have chosen Source 2 because: The sole purpose of the webpage is to give information about the free church and it is probably written by someone who has both a lot of knowledge and personal experience of that particular free church.

I have not chosen Source 1 because: You may not know where the student got all the information for their text and the text may be personal and contain more opinions and personal arguments than facts.

I have not chosen Source 3 because: I don’t think blogs are a reliable source. Anyone can make a blog post about anything without really knowing anything about it. And you can write whatever you want on a blog, so you have no idea what’s there.

As seen from the answer, the student shows an ability to choose more valid sources and an understanding the biases of Sources 1 and 2, although not the biases of Sources 4 and 2. The item demands the ability to conduct a general source criticism and to evaluate different sources, rather than the textual criticisms that have a stronger foundation in religious studies or a source criticism that goes into detail about the particular Christian free church of the Laestadians. However, source criticism within religious studies as a field also entails the general features of source criticism in focus in Item 23, so in that sense we would argue that a correct answer to the questions requires the student to have acquired PK in RE.

Muller and Young (

2019), in response to criticism of the PK theory as being too much based on the knowledge produced by the natural sciences, argues that social science subjects have different criteria for PK, and that in relation to these subjects, it is necessary to build on knowledge acquired in other subjects to build PK in a specific subject. In that sense, the ability to carry out a general source criticism could be seen as PK in RE.

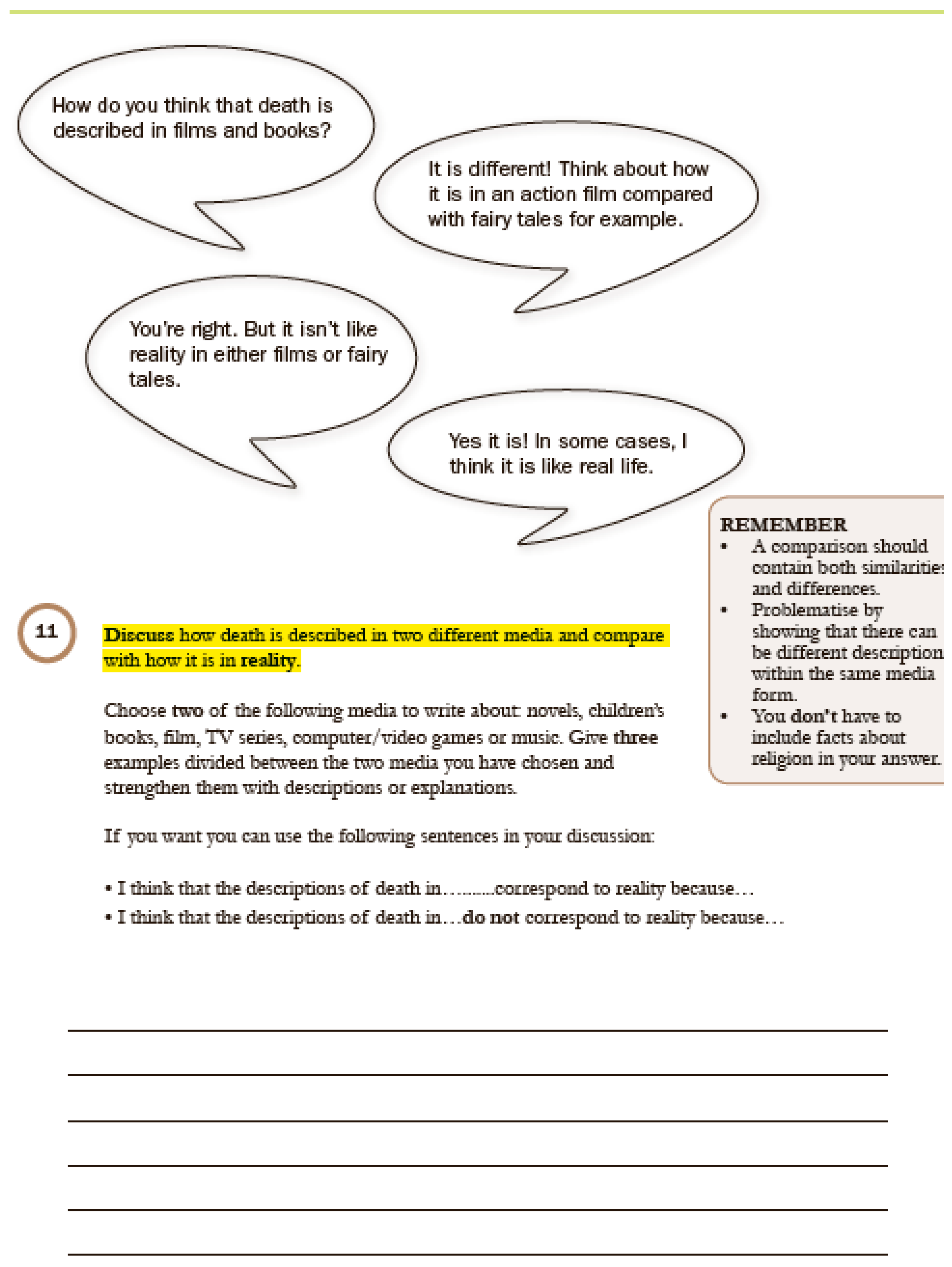

7.5. Students’ Everyday Experiences: Descriptions of Death

As mentioned above, the theory of PK was established as a response to a perceived overfocus on everyday knowledge and experiences in the curriculum and educational research (

Young 2008). The argument is that although it is essential for educators to connect to students’ everyday knowledge and experiences in pedagogical practice, the goal of education should be to enable students to get access to knowledge that goes beyond their everyday knowledge, acquired in everyday life. Item 11 is an example of a task that has a focus on everyday experiences of the student rather than powerful knowledge. In contrast to the items discussed above, this item is rather open to personal and/or general outlooks on life, and reasoning about such outlooks, in terms of personal faith perspectives. In Item 11, a picture from the film

Twilight is shown with the following text, “In the Twilight films, questions about death are an important element”. Four speech bubbles are shown next to the picture with the following comments: (i) “How do you think that death is described in films and books?”, (ii) “It is different! Think about how it is in an action film compared with fairy tales for example.” (iii) “You’re right. But it isn’t like reality in either films or fairy tales.” (iv) “Yes it is! In some cases, I think it’s like real life”. Then the students get some specific instructions, first to “

Discuss how death is described in two different media and compare with how it is in

reality”. They are also instructed to “Choose

two of the following media to write about: novels, children’s books, film, TV series, computer/video games or music.” and, “Give

three examples divided between the two media you have chosen and strengthen them with descriptions or explanations”. The students also get some optional information to use, telling them, “If you want you can use the following sentences in your discussion: I think that the descriptions of death in … correspond to reality because…, I think that the descriptions of death in…

do not correspond to reality because…”. Lastly, the item also includes a reminder that “a comparison should contain both similarities and differences”, and that they should, “problematize, by showing that there can be different descriptions within the same media form”, and further that they “

don’t have to include facts about religion” in their answers.

As discussed above, PK enables students to see beyond their everyday experiences. Obviously, the instructions and the references in Item 11 are constructed to focus mainly on students’ everyday experience, and as such do not require much powerful knowledge. Rather, the item relates to students’ general outlooks and personal principles regarding death. This tendency is also noticeable in the student answer below.

Item 11, student answer.

I think that the descriptions of death in movies can be different from reality. Especially in action movies, where a lot of people die and often the consequences are not shown, like grief and in the case of murder, e.g., punishment. In some movies I suppose it’s alright, as movies can show a lot of love and sadness and consequences. Even relief. Then there can be similarities to reality because often there are a lot of emotions and suffering. In video games, it is usually very different from reality because it is often about killing as many people as possible and in most games no emotions are shown. Even if there is a war theme in the game, and that has similarities to war in real life, where you also have to kill, it takes a lot from a soldier to kill someone and it is often very hard.

The student uses his/her everyday experiences of descriptions of death in popular media such as movies and video games, and reflections based on everyday knowledge about the difficulties of killing people. The student’s answer does not include any references to subject knowledge, concepts, or theories to comprehend descriptions of death on an historical or societal level, in relation, for example, to any dominant descriptions and conceptions of death in different cultures. From a PK perspective, the problem is not that students are allowed to express or relate to their everyday experiences/knowledge in the classroom, as successful teaching entails connecting to such experiences/knowledge. As stated by

Muller and Young (

2019), the problem is when such experiences/knowledge become the goal of education, and in that sense, one could consider Item 11 to lack PK.

7.6. Summarizing the Result

The analysis of the 2017 Swedish national test in RE revealed clear indications that items have different instructions resulting in stronger and weaker aspects of powerful knowledge being shown. Items regarded as having the strongest aspects were Items 7, 9, 19, and 23. Item 11 is considered an example of an item having weak aspects. The strong items have common distinguishing features, often starting with a certain subject- and discipline-specific knowledge of a religion, or ethical model (maybe with the exception of Item 23) and then including elements of, for example, comparing this knowledge to other specific RE knowledge (that the student must know, or be able to use from sources given in the items). Further, the items instruct students to reason and/or argue about, for example, similarities and differences regarding the specific subject matter at hand. Some items include all these features, others one or two.

The weak powerful knowledge item presented, Item 11, also has a distinguishing feature. It starts off by highlighting a well-known film inviting students to think about outlooks on life and death. Second, it pinpoints certain principles and issues that should be at the center of the answer, focusing on common existential issues, requiring general abilities to reflect on and discuss issues of death and existential thoughts. Consequently, the item differs from the strong powerful knowledge ones by not targeting certain subject- and discipline-specific knowledge of religion and/or comparison of such, and not asking for examples of similarities and differences regarding the specific subject matter.

8. Discussion

The purpose of the study was first to illuminate whether aspects of powerful knowledge could be found in items in the 2017 Swedish national tests in RE for Grade 9, and secondly to illuminate whether such aspects were manifested in student responses to the items. The results show that the national tests in RE and student answers manifest several different aspects of PK in RE that have been discussed in previous research, such as “subject knowledge” and “ethical principles”. As the national tests are constructed to measure the learning goals of the syllabus, and as we know from previous research that the 2011 RE syllabus had a focus on subject knowledge and disciplinary knowledge (

Von Brömssen et al. 2020;

Jonsson 2016), this result was not surprising. Likewise, as the 2011 RE syllabus also encompasses goals that focus on students’ life-worlds and everyday experiences, it was not surprising to find an item that was not related to PK. As we know, as mentioned above, that national tests are consequential for pedagogical practice, the focus on everyday experiences in the national test could be seen as problematic from a PK perspective.

Young and Lambert (

2014, p. 98) stress that schools should be a place where the world is treated as “object of thought”, not a “place of experience”. However, even in research sympathetic to the theory of PK, this has been a controversial issue.

Roberts (

2014), for example, argues that if every day experiences and knowledge are absent in the curriculum, it will be neglected in pedagogical practice. Regardless of whether Roberts’ argument is valid, one could argue from a PK perspective that even if a question in a national test has a focus on students’ everyday experiences/knowledge, it should be constructed in such a way that in order to receive the highest grade, the student is required to make some kind of connection to more abstract concepts and/or more general ways of framing a certain issue that relates to aspects of PK.

Osbeck (

2020) raised the concern, building on conversations with school teachers, that the vagueness of ethics in the Swedish curriculum would lead to the national test instead setting the standard for an appropriate ethics education. Despite this valid concern, the framing of ethics in Item 9 in the 2017 national test in RE, in our interpretation, puts PK to the fore of ethics education. Maybe questions with a focus on ethics in national tests in RE can be used as a model for clarifying the vagueness in the curriculum in relation to ethics in a future revision?

Franck (

2021a),

Franck and Thalén (

2023) and

Osbeck (

2020) emphasize that research that applies the theory of PK to RE is an emerging field, and that many issues concerning how PK can be defined in relation to RE still have to be worked out. In the theory section of the present article, we give some examples of aspects of PK in RE in relation to knowledge and abilities, developed from the definitions given by Franck and Osbeck. The relevance of these examples needs to be discussed further, but for the purpose of framing the analysis of PK in the RE national test, we would say they worked well. A weakness in the still small field of PK studies of RE is a vagueness regarding the definitions of PK in RE. Further, the issue of relevance of PK in RE needs to be developed in relation to confessional RE. However, the result in the present study relates to RE as a non-confessional subject. We hope our examples/concepts can contribute to clarifying the definitions of PK in RE and can be built on further in future research.

Deng (

2020), even though sympathetic to the defense of subject knowledge in the field of curriculum studies, criticizes the theory of PK for neglecting the normative dimension of the purpose of schools, and suggests that this purpose has a wider socio-cultural dimension than the transmission of subject knowledge. In relation to a subject like RE, which has an explicit normative dimension, this is a valid criticism. There are possible limitations to PK as a theory in relation to the normative dimension of education (see

Biesta 2021) and the relevance of a subject like RE in particular (

White 2019). The normative dimension of social science has been highlighted by critical realists, who are otherwise staunch defenders of the claims to truth and the validity of knowledge produced by social science (

Collier 1994) and have been a strong influence in the emergence of the theory of PK in educational research (

Wheelahan 2012). To answer Deng’s critique, and to make PK relevant for school subjects with strong bases in humanistic and social sciences, PK as a theory needs to integrate and elaborate on the normative dimension of social science and its possible consequences for these school subjects and the curriculum.