1. Introduction

The extensive support programmes for entrepreneurship worldwide testify to its crucial role in the social and economic development of today’s society (

Atiase et al. 2018;

Medeiros et al. 2020). While entrepreneurial growth offers consumers a wide range of product options, the industrialisation that creates these products has been accompanied by alarming levels of environmental degradation (including pollution, land degradation, natural resource depletion, climate change, and global warming (

Halkos and Polemis 2017;

Gulistan et al. 2020), generating increased concern. Approximately 75 per cent of the world’s land is deteriorated, caused mainly by unsustainable human choices and endangering the survival of over three billion people (

Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services 2019). For poorer nations, environmental restoration is cost prohibitive. For instance, the annual cost of environmental degradation to Zimbabwean society in 2017 was estimated at USD 382 million, around 6 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product at the time (

United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification 2017). It is suggested that preventive measures are one of the most cost-effective ways to avert the global catastrophe (

Basu et al. 2019), hence the call for businesses to pursue a balance of environmental, economic, and social value creation (also known as sustainable entrepreneurship) in accordance with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Higher education institutions contribute to the sustainability action plan by implementing eco-friendly practices and preparing future generations by creating indispensable opportunities to study the latest advancements and developmental requirements for sustainable communities (

Habib et al. 2021). In many industrialised nations, higher education institutions offering entrepreneurship training and education are reorienting their educational curricula to inspire their students and graduates to pursue sustainable business following the SDGs (

Lourenço et al. 2012). In Germany, for example, state-owned universities have increasingly taken a leading position in regional and economic sustainability in recent years through university-related funding programmes for sustainable management in addition to teaching and research activities (

Wagner et al. 2021). Even with this paradigm shift in place, there are worries about university departments’ ability to produce alumni who are sustainability-conscious, given their individualist “profit first” culture (

Slater and Dixon-Fowler 2010;

Giacalone and Thompson 2006). The prioritization of profits seems to threaten the institutional acceptance of sustainability as a key objective. This is because the implementation of sustainability actions increases the likelihood of declining revenue, a key measure of success for business entities.

Despite a growing body of literature on the role of higher education in sustainable development, research on the relationship between the values instilled in students by for-profit institutions such as business schools and their intent to initiate sustainability initiatives is limited. Even though values and behavioural intentions have a long history in social psychology, it is only recently that they have been examined together in entrepreneurial research (

Fayolle et al. 2014;

Kruse et al. 2019;

Liñán et al. 2016;

Hueso et al. 2021), such that low-income countries such as Zimbabwe are under-represented in the literature. As previously indicated, developing countries are overburdened by the concomitant costs of environmental deterioration.

Several studies have examined the different mechanisms through which values are associated with entrepreneurial intentions, including those oriented toward sustainability (

Azanza et al. 2007;

Gorgievski et al. 2018;

Mcdonald 2014;

Rantanen and Toikko 2017). However,

Hueso et al. (

2021) argue that additional research is necessary before a complete understanding of the relationship can be attained. The uncertainty in the literature on the collective influence of human values and predictors of the theory of planned behaviour on sustainability-related entrepreneurial intentions is thus the research gap. Previous research on the collective influence of values and predictors of intentions in the theory has primarily focused on general entrepreneurial intentions.

Fayolle et al. (

2014) recommend that researchers investigate intention in a variety of entrepreneurial scenarios (e.g., corporate, sustainability, social, or technology-related) in order to rejuvenate and broaden the scope of entrepreneurship intentions research. Because of this, the current study applies

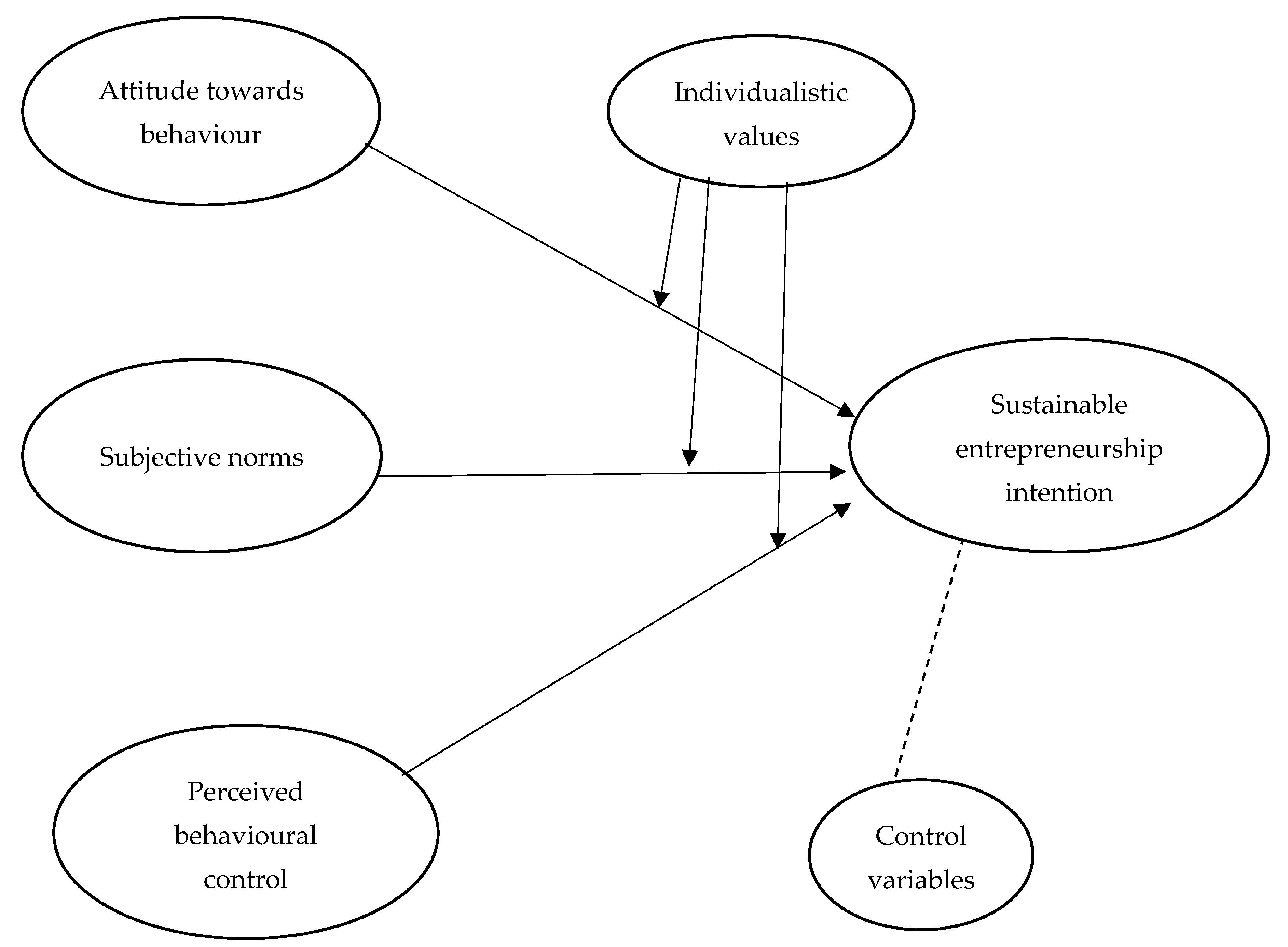

Ajzen’s (

1991) theory of planned behaviour to develop a model for determining the predictors of sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship intentions among selected Zimbabwean business school students. Individualistic values, it is postulated, moderate the influence of attitude toward behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control on sustainable entrepreneurship intentions. As a result, the overarching research question is as follows:

Do individualistic values exert a moderating effect on how attitudes toward behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control affect students’ intention to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship?

It is useful to explore the parameters mentioned in the research question and their links for different reasons. To begin with, the findings contribute to a better understanding of the dynamics behind the genesis of complex planned behaviours such as sustainable entrepreneurship. Secondly, individualistic values, which are characterised as a cultural dimension consisting of “a preference for a loosely-knit social framework in which individuals are expected to look after only themselves and their immediate circle” (

Rantanen and Toikko 2017, p. 292), are an integral part of personal goal setting (

Bardi and Schwartz 2003) and serve as action guides in difficult situations such as deciding whether to adopt sustainable business practices (

Gorgievski et al. 2018). Business school students are appropriate targets for the study because many of them oversee or even own businesses and may eventually launch new ventures with ecological implications. Likewise, they are socialised to the individualistic business school philosophy of ‘profit-first’ and thus serve as ideal data sources for the study. Finally, knowing the relationship between students’ values and intentions for sustainable entrepreneurship potentially affects sustainable entrepreneurship and development policy.

The next section provides an overview of the existing literature on the variables under consideration. Afterwards, an explanation of the methodological approaches and procedures used in the study’s execution follows. The section on the study’s findings is then presented. Finally, a discussion of the findings is offered, along with its implications and limitations, as well as suggested study areas.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether individualistic values affected the linkages between sustainable entrepreneurship intention and its three predictors according to the theory of planned behaviour. Equally, it sought to establish whether the assumptions of the

Ajzen’s (

1991) model could be used to predict the sustainable entrepreneurship intention of selected business school students in a developing country.

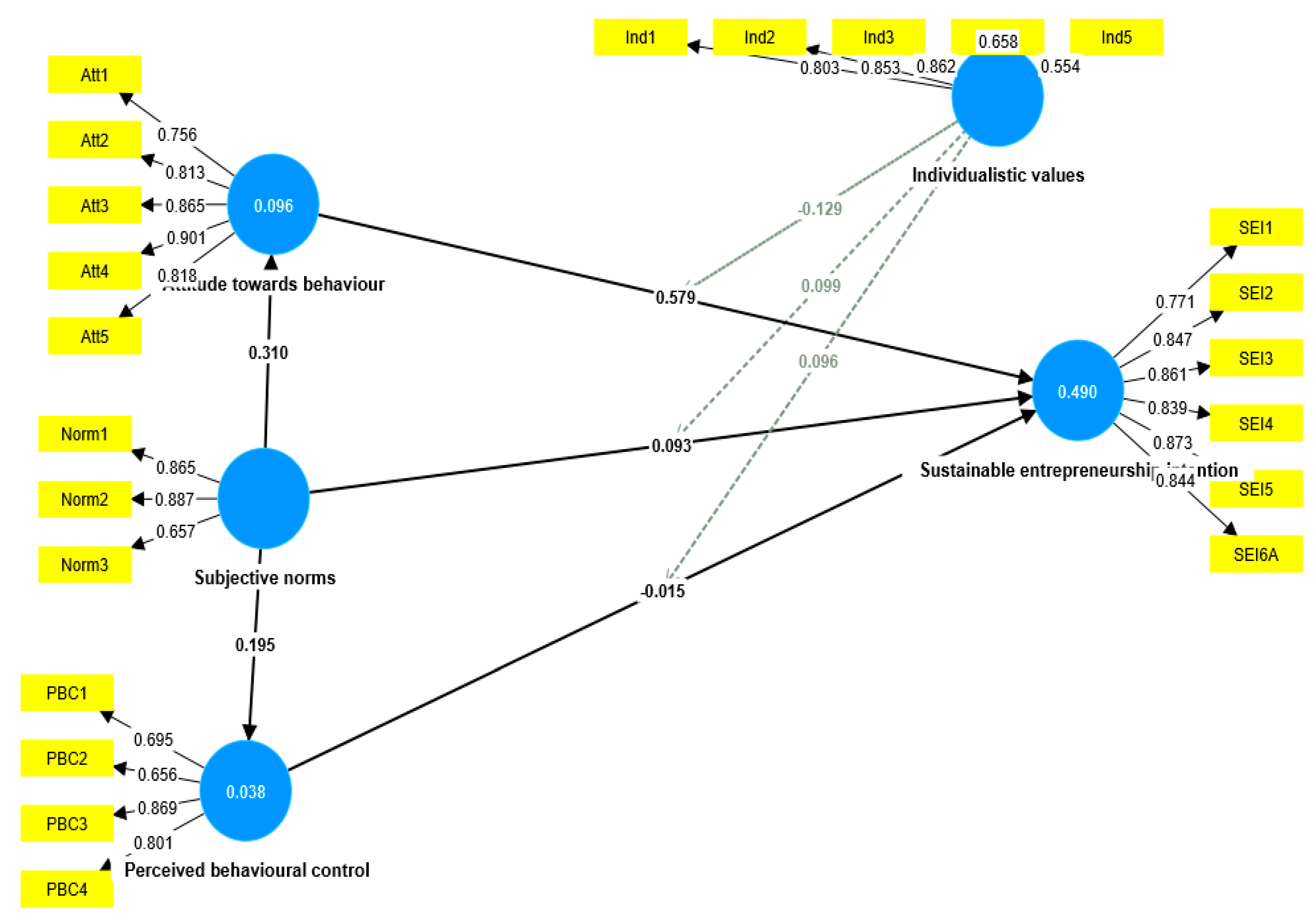

Firstly, the most prominent outcome from this study is that attitude toward behaviour had a strong positive link with the intention to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. The results are consistent with earlier research in the realms of entrepreneurship and prosocial behaviour that used the theory of planned behaviour as a reference frame (

Chekima et al. 2016;

Gatersleben et al. 2014) and confirmed the major role of attitudes in the creation of behavioural intention and, subsequently, behaviour. The outcome corroborates recent findings by

Rueda Barrios et al. (

2022) and

Boubker et al. (

2022), which also confirmed a positive relationship between attitude towards behaviour and sustainable entrepreneurial intentions.

Secondly, the direct association between subjective norms and sustainable entrepreneurship intention was found to be statistically non-significant in this study. However, an indirect effect of social norms on sustainable entrepreneurship intention was confirmed, which was fully mediated by attitude towards behaviour. While this relationship pattern is not in sync with the assumptions of the theory of planned behaviour, it is consistent with observations of

Fenech et al. (

2019),

Autio et al. (

2001), and

Liñán et al. (

2011a) that the relationship between subjective norms and behavioural intentions is at best weak and sometimes non-significant. The result supports

Marques et al.’s (

2012) and

García-Rodríguez et al.’s (

2015) hypothesis that subject norms may influence entrepreneurial ambitions as well as the other two determinants, attitude toward behaviour and perceived behavioural control.

The most unexpected observation is that the association between perceived behavioural control and sustainable entrepreneurship intentions was not statistically significant. This finding contradicts multiple research that claimed that one’s confidence in performing an activity played a substantial role in one’s intention to undertake that activity (

García-Rodríguez et al. 2015;

Karimi et al. 2015;

Malebana and Swanepoel 2015). One possible explanation for these findings is that for the respondents, who were postgraduate business school students immersed in a profit-first environment, pursuing a commercial enterprise that went beyond the primary business goal of profits was a sentimental decision rather than one based on perceived abilities to perform. As a result, attitudes influenced their propensity to participate in sustainable practices more than perceived capabilities. This finding, however, is consistent with that of

Vuorio et al. (

2018), who found no link between perceived feasibility and sustainability-oriented entrepreneurial intentions, and

Ayob et al. (

2013), who discovered no relationship between perceived entrepreneurial feasibility and social entrepreneurial intentions.

Individualistic values have previously been shown to influence different forms of entrepreneurial intentions in students (

Downes et al. 2017;

Liñán et al. 2016). This appeared not to be the case in this study. The direct association between individualistic values and intention to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship was not statistically significant. Similarly, the theorised moderating effect of individualistic values on the relationship between the three antecedents of intentions specified in the theory of planned behaviour and the intention to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship was also found not to be significant. The findings contradict the suggestions by

Fayolle et al. (

2014) and

Delanoë-Gueguen and Liñán (

2019) that personal values may moderate the relationships between predictor and independent variables in the theory of planned behaviour. The observed result, however, is consistent with

Verplanken and Holland’s (

2002) assertion that though personal values are more enduring constructs than attitudes, they are not always invoked when individuals make decisions and actions. Thus, the respondents’ choice to pursue sustainable entrepreneurship may be opportunistic and unrelated to their value system. As with the unpredictability in the attitude–behaviour relationship, an ambiguity in the value–behaviour connection can also be inferred.

6. Conclusions

In this section, theoretical and practical applications of the study, as well as the limitations and areas for further research, are proposed.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

The paper represents a notable step forward in gaining a deeper knowledge of sustainable entrepreneurship intentions and has practical consequences in the unique environment of Zimbabwean business schools. Prior studies have highlighted the importance of higher education institutions in enhancing sustainability performance in societies (

Dagiliūtė and Liobikienė 2015;

Yuan et al. 2013). The study investigated a novel conceptual model that incorporated the individualistic values variable to see if assumptions of the theory of planned behaviour can be applied to the field of sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship. The study discovered statistically insignificant direct correlations between perceived behavioural control and sustainable entrepreneurship intentions, as well as subjective norms and sustainable entrepreneurial intentions. It also disconfirmed the hypothesised moderating effect of individualistic values in the numerous interactions between main constructs in the theory of planned behaviour. However, it confirmed that attitude toward a behaviour is the most powerful predictor of intention. It also lends evidence to the notion that the influence of subjective norms on sustainable entrepreneurship intention in the theory of planned behaviour is potentially mediated by other variables. Overall, the study findings illustrate the possibility of context-specific deviations in the theory of planned behaviour’s application.

6.2. Practical Implications

The results also have practical implications. They suggest that the most important determinant of sustainable entrepreneurship intention is the attitude towards behaviour. Given this, business schools should focus their efforts primarily on shifting the attitudes of their targeted audiences to nurture entrepreneurs who are more oriented toward sustainable business methods. Such efforts could take the form of sustainability-related curriculum content and activities aimed at increasing participants’ understanding of the benefits of sustainable entrepreneurship as well as their motivation and capabilities to pursue it.

Additionally, the study discovered that subjective norms had a substantial indirect effect on individuals’ choice to pursue sustainable business practices via their attitude toward behaviour. The implication is that business schools, as critical social institutions in their students’ lives, should deliberately foster an institutional environment that stimulates sustainable entrepreneurship. This is possible if business schools incorporate the concept of sustainability into their fundamental values and students believe the institutions live according to the stated principle. Business schools can have a social influence on their students by adopting a holistic approach to sustainability that encompasses teaching, research, institutional processes, physical infrastructure, community involvement, and stakeholder relationships.

6.3. Limitations and Areas for Further Research

While the findings of this study are critical to understanding sustainable entrepreneurial intentions, the research has some limitations, most notably those on the representativeness of the outcomes. While a census of all applicable respondents was attempted, participation was voluntary, and approximately 66.8% of the target population responded. Thus, the statistical representativeness of the results could have been undermined.

Furthermore, the study relied on the perspectives of respondents drawn from postgraduate students from only two business schools in Zimbabwe. As a result, the insights gathered are bound to narrow contexts and should be used with caution. In future investigations, it may be beneficial to undertake a similar study, but which targets students from all the business schools in Zimbabwe so that more representative inferences can be drawn. Another detailed study on the effects of a more comprehensive range of human values (not individualism only) on sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship is also proposed for future investigation.

The survey was cross-sectional in design, gathering opinions from students only when they had completed a postgraduate course in entrepreneurship. Future research should strengthen the credibility of the findings by using a longitudinal strategy in which there are pre-tests and post-tests of student opinions when they enrol and when they graduate from the entrepreneurship course.