Are Companies Committed to Preventing Gender Violence against Women? The Role of the Manager’s Implicit Resistance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose

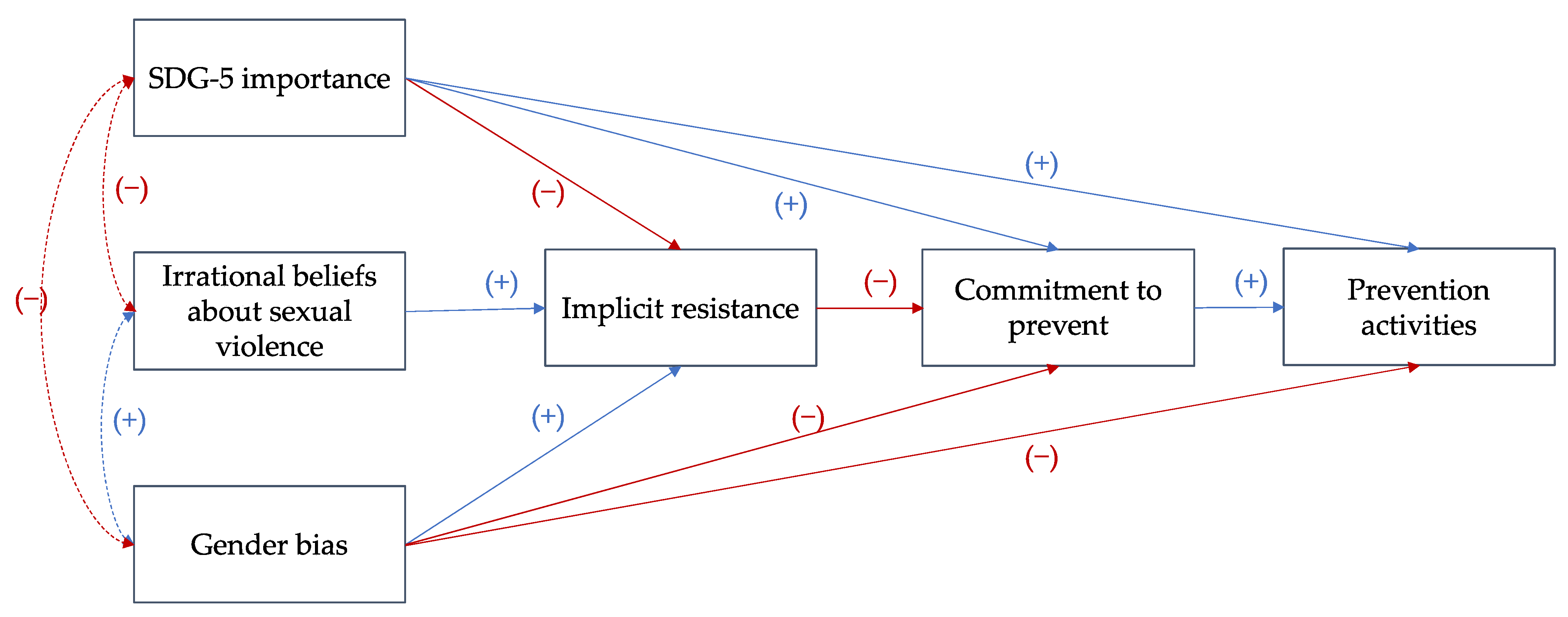

1.2. Conceptual Model

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Sampling Units

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis Procedure

3. Results

3.1. Managers’ Commitment to Prevention

3.2. Managers’ Implicit Resistance

3.3. Gender Bias and Irrational Beliefs about Sexual Violence

3.4. Gender Differences

3.5. The Role of Implicit Managerial Resistance

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alter, Karen J., and Michael Zürn. 2020. Conceptualising backlash politics: Introduction to a special issue on backlash politics in comparison. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 4: 563–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, Shiu-Yik, Ming Dong, and Andreanne Tremblay. 2022. How Much Does Workplace Sexual Harassment Hurt Firm Value? SSRN Electronic Journal, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, Jonathan, and Achim Wennmann. 2017. Business engagement in violence prevention and peace-building: The case of Kenya. Conflict, Security & Development 6: 451–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 6: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, Sarah, Alessandra Guedes, Ana P. Ruiz-Celis, and Jennifer Adams Mendoza. 2019. Intimate partner violence in the Americas: A systematic review and reanalysis of national prevalence estimates. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 43: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brendel, Christine, Franziska Gutzeit, and Jazmín Ponce. 2017. Safe enterprises: Implementation Experiences of Involving the Private Sector in Preventing and Fighting Violence Against Women in Perú. In Transformation, Politics and Implementation: Smart Implementation in Governance Programs. Edited by Renate Kirsch, Elke Siehl and Albrecht Stockmayer. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH, pp. 195–220. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv941tdt.13#metadata_info_tab_contents (accessed on 8 October 2022).

- Brescoll, Victoria, Tyler Okimoto, and Andrea Vial. 2018. You’ve Come a Long Way…Maybe: How Moral Emotions Trigger Backlash Against Women Leaders. Journal of Social Issues 1: 144–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, Kimberly E., Laurie A. Rudman, Janell C. Fetterolf, and Danielle M. Young. 2019. Paying a Price for Domestic Equality: Risk Factors for Backlash Against Nontraditional Husbands. Gender 36: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, Linda, Sue Williamson, and Meraiah Foley. 2020. Understanding, ownership, or resistance: Explaining persistent gender inequality in public services. Gender, Work and Organization 1: 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortis, Natasha, Meraiah Foley, and Sue Williamson. 2022. Change agents or defending the status quo? How seniors leaders frame workplace gender equality. Gender, Work and Organization 1: 205–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbin, Frank, and Alexandra Kalev. 2019. The promise and peril of sexual harassment programs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 25: 12255–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbin, Frank, and Alexandra Kalev. 2020. Why sexual harassment programs backfire. Harvard Business Review 3: 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Kathryn J., and Jane F. Maley. 2021. Barriers to women in senior leadership: How unconscious bias is holding back Australia’s economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources 2: 204–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, Susan. 1991. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women. New York: Crown Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Alexandra N., Danu Anthony Stinson, and Anastasija Kalajdzic. 2019. Unpacking Backlash: Individual and Contextual Moderators of Bias against Female Professors. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 5: 305–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, Michael, Molly Dragiewicz, and Bob Pease. 2021. Resistance and backlash to gender equality. Australian Journal of Social 3: 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GenderLab. 2021. Primer informe ELSA sobre acoso sexual laboral en el Perú. Available online: https://bit.ly/3HhOnks (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Gramazio, Sarah, Mara Cadinu, Stefano Pagliaro, and Maria Giuseppina Pacilli. 2021. Sexualization of Sexual Harassment Victims Reduces Bystanders’ Help: The Mediating Role of Attribution of Immorality and Blame. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 13–14: 6073–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grangeiro, Rebeca da Rocha, Alessandro Teixeira Rezende, Manoel Bastos Gomes Neto, Jailson Santana Carneiro, and Catherine Esnard. 2022. Queen Bee Phenomenon Scale: Psychometric Evidence in the Brazilian Context. BAR—Brazilian Administration Review 1: 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph, Barry Babin, and Nina Krey. 2017. Covariance-based structural equation modeling in the Journal of Advertising: Review and recommendations. Journal of Advertising 1: 163–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harding, Nancy H., Jackie Ford, and Hugh Lee. 2017. Towards a Performative Theory of Resistance: Senior Managers and Revolting Subject(ivitie)s. Organization Studies 9: 1209–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, Chloe G., Alison Crossley, and Shelley J. Correll. 2018. Leader messaging and attitudes toward sexual violence. Socius 4: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hastings, Rebecca R. 2011. Diversity Training Pitfalls to Avoid. SHRM. Available online: https://bit.ly/3gGub0L (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York and London: The Guilford Press, pp. 3–692. [Google Scholar]

- Humbert, Anne, Elisabeth Kelan, and Marieke Van den Brink. 2018. The Perils of Gender Beliefs for Men Leaders as Change Agents for Gender Equality. European Management Review 4: 1143–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello, Vincenzo, Giulia Valsecchi, Jacques Berent, Islam Borinca, and Juan Manuel Falomir Pichastor. 2021. The impact of masculinity beliefs and political ideologies on men’s backlash against non-traditional men: The moderating role of perceived Men’s feminization. International Review of Social Psychology 1: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infanger, Martina, Laurie A. Rudman, and Sabine Sczesny. 2016. Sex as a source of power? Backlash against self-sexualizing women. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 1: 110–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática [INEI]. 2019. Encuesta Nacional sobre Relaciones Sociales ENARES 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/3VA6lmk (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática [INEI]. 2022a. Demografía empresarial en el Perú. Segundo Trimestre 2022. Informe técnico 3. Available online: https://bit.ly/3GIuFOv (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática [INEI]. 2022b. Perú: Estructura Empresarial 2020. Available online: https://cutt.ly/g1edWPc (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática [INEI]. 2022c. Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar ENDES 2021. Available online: https://bit.ly/3uwenks (accessed on 7 July 2022).

- International Labour Organization [ILO]. 2019. Handbook Addressing Violence and Harassment against Women in the World of Work. New York: UN Women Headquarters, pp. 1–99. Available online: https://cutt.ly/012BJNo (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Kelan, Elizabeth K. 2009. Gender Fatigue: The Ideological Dilemma of Gender Neutrality and Discrimination in Organizations. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 3: 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelan, Elizabeth K., and Patricia Wratil. 2020. CEOs as agents of change and continuity. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion 5: 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex. B. 2016. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed. New York and London: The Guilford Press, pp. 1–534. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, Deborah, and Kathleen L. McGinn. 2008. Beyond Gender and Negotiation to Gendered Negotiations. Harvard Business School (HBS) 09-064. Boston: Harvard Business School, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Filho, Walter, Marina Kovaleva, Stella Tsani, Diana-Mihaela Țîrcă, Chris Shiel, Maria Alzira Pimenta Dinis, Melanie Nicolau, Mihaela Sima, Barbara Fritzen, Amanda Lange Salvia, and et al. 2022. Promoting gender equality across the sustainable development goals. Environmental. Development and Sustainability, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Ziyi, and Yong Zheng. 2022. Blame of Rape Victims and Perpetrators in China: The Role of Gender, Rape Myth Acceptance, and Situational Factors. Sex Roles 87: 167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, Isabel, and David Ralston. 2002. Corporate Social Responsibility in Europe and the U.S.: Insights from Businesses’ Self-presentations. Journal of International Business Studies 33: 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansbridge, Jane, and Shauna L. Shames. 2008. Toward a Theory of Backlash: Dynamic Resistance and the Central Role of Power. Politics and Gender 4: 623–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moss-Racusin, Corinne, Julie E. Phelan, and Laurie A. Rudman. 2010. When men break the gender rules: Status incongruity and backlash against modest men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 2: 140–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naciones Unidas. 2018. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: Una Oportunidad para América Latina y el Caribe (LC/G.2681-P/Rev.3). Available online: https://bit.ly/2UtPJwT (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- O’Neil, Deborah, and Margaret M. Hopkins. 2015. The impact of gendered organizational systems on women’s career advancement. Frontiers in Psychology 61: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opoku, Alex, and Ninarita Williams. 2018. Second-generation gender bias: An exploratory study of the women’s leadership gap in a UK construction organization. International Journal of Ethics and Systems 1: 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orgeira-Crespo, Pedro, Carla Míguez-Álvarez, Miguel Cuevas-Alonso, and Elena Rivo-López. 2021. An analysis of unconscious gender bias in academic texts by means of a decision algorithm. PLoS ONE 9: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, Julie E., and Laurie A. Rudman. 2010. Prejudice Toward Female Leaders: Backlash Effects and Women’s Impression Management Dilemma. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 10: 807–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, Tenko, and Gregory Hancock. 2005. Examining change in maximal reliability for multiple-component measuring instruments. The British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 1: 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Yves. 2012. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software 2: 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudman, Laurie A., and Kimberly Fairchild. 2004. Reactions to counter stereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2: 157–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudman, Laurie A., and Julie E. Phelan. 2008. Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior 28: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, Laurie A., Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, Julie E. Phelan, and Sanne Nauts. 2012a. Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 1: 165–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, Laurie A., Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, Peter Glick, and Julie E. Phelan. 2012b. Reactions to Vanguards. Advances in Backlash Theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 45: 167–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, Lynnmarie, Mathieu Maheu-Giroux, Heidi Stöckl, Sarah R. Meyer, and Claudia García-Moreno. 2022. Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet 10327: 803–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, Randall, and Richard Lomax. 2015. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sidanius, Jim, Felicia Pratto, Colette Van Laar, and Shana Levin. 2004. Social Dominance Theory: Its Agenda and Method. Political Psychology 6: 845–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soklaridis, Sophie, Catherine Zahn, Ayelet Kuper, Deborah Gillis, Valerie H. Taylor, and Cynthia Whitehead. 2018. Medicine and Society Men’s Fear of Mentoring in the #metoo Era—What’s at Stake for Academic Medicine? The New England Journal of Medicine 23: 2270–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Belmont Report. Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. 1979. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Available online: https://bit.ly/2JrDY4j (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Thomas, Kecia M., and Victoria C. Plaut. 2008. The Many Faces of Diversity Resistance in the Workplace. In Diversity Resistance in Organizations. Edited by Thomas Kecia M. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, pp. 1–22. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2008-06292-001 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Van der Bruggen, Madeleine, and Amy Grubb. 2014. A review of the literature relating to rape victim blaming: An analysis of the impact of observer and victim characteristics on attribution of blame in rape cases. Aggression and Violent Behavior 5: 523–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vara-Horna, Arístides. 2013. Los Costos Empresariales de la Violencia Contra las Mujeres en el Perú. Una Estimación del Impacto de la Violencia Contra las Mujeres en Relaciones de Pareja en la Productividad Laboral de las Empresas Peruanas. Lima: GIZ & USMP, pp. 4–179. Available online: https://bit.ly/3tXMsJH (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Vara-Horna, Arístides. 2016. Impacto de la violencia contra las mujeres en la productividad laboral: Una comparación internacional entre Bolivia, Paraguay y Perú. Lima: GIZ, pp. 1–37. Available online: https://bit.ly/3EBS7KA (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Vara-Horna, Arístides. 2019. Los costos empresariales de la violencia contra las mujeres en Ecuador. El impacto invisible en las grandes y medianas empresas privadas de la violencia contra las mujeres en relaciones de pareja (VcM): 2018. Quito: PreViMujer-GIZ, pp. 9–73. Available online: https://bit.ly/3EWlo3Q (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Vara-Horna, Arístides. 2020. ¿Cómo prevenir la violencia contra las mujeres mediante la inserción laboral? Sistematización y recomendaciones en base a experiencias de trabajo conjunto entre el sector privado y público. Ministerio de la Mujer y Poblaciones Vulnerables & Cooperación Española. Disponible en línea: Work. Available online: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17133.41448 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Vara-Horna, Arístides. 2021. De la Evidencia a la Prevención. La Violencia Contra las Mujeres en las Universidades. Diagnóstico, Costos, Revisión Sistemática y Modelo Preventivo en Ecuador. Quito: PreViMujer-GIZ, pp. 2–244. [Google Scholar]

- Vara-Horna, Arístides. 2022. Violencia contra las mujeres y productividad laboral en las empresas de Bolivia: Prevalencia e impacto en el contexto pandémico 2021. La Paz: Proyecto PreVio de la Agencia de Cooperación Alemana GIZ, pp. 2–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Melissa J., and Larissa Z. Tiedens. 2016. The subtle suspension of backlash: A meta-analysis of penalties for women’s implicit and explicit dominance behavior. Psychological Bulletin 2: 165–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, Sue. 2019. Backlash, gender fatigue and organisational change: AIRAANZ 2019 presidential address. Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 1: 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williamson, Sue, Colley Linda, Foley Meraiah, and Cooper Rae. 2018. The Role of Middle Managers in Progressing Gender Equity in the Public Sector. Canberra: UNSW Canberra, pp. 3–37. Available online: https://n9.cl/h42u9 (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Willness, Chelsea R., Steel Piers, and Lee Kibeom. 2007. A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of workplace sexual harassment. Personnel Psychology 1: 127–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Ailun, Tao Jiajia, Li Hongyi, and Westlund Hans. 2022. Will female managers support gender equality? The study of “Queen Bee” syndrome in China. Asian Journal of Social Psychology 3: 544–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs, Dimensions, and Items | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|

| Implicit resistance to prevention (second-order construct) (Average extracted variance = 66.4%/omega reliability = 0.866) | |

| Passive denial (omega reliability = 0.807) | 0.668 |

| 0.589 |

| 0.838 |

| 0.843 |

| Avoidance of responsibility (alpha reliability = 0.637) | 0.757 |

| 0.669 |

| 0.763 |

| Strategic disarmament (omega reliability = 0.708) | 0.842 |

| 0.682 |

| 0.600 |

| 0.740 |

| Defensive disapproval (omega reliability = 0.837) | 0.965 |

| 0.765 |

| 0.831 |

| 0.760 |

| Commitment to prevention (Average extracted variance = 70.7%/omega reliability = 0.771) | |

| 0.740 |

| 0.720 |

| 0.766 |

| ODS-5 Value | Implicit Resistance | Commitment Prevention | Gender Bias | Irrational Beliefs to S.V. | Prevention Activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (women) | −0.189 ** | 0.095 * | −0.056 | 0.257 ** | 0.108 * | 0.079 * |

| Age | −0.105 ** | 0.070 | −0.103 * | −0.001 | 0.046 | −0.071 |

| Children number | −0.110 ** | 0.073 | −0.075 | 0.023 | 0.102 ** | −0.034 |

| Education level | −0.018 | −0.127 ** | 0.114 ** | −0.126 ** | −0.127 ** | 0.148 ** |

| Seniority in the position | −0.101 ** | 0.117 ** | −0.044 | −0.001 | 0.060 | −0.094 * |

| Number of workers | 0.005 | −0.163 ** | 0.048 | −0.026 | −0.130 ** | 0.329 ** |

| % of female workers | 0.036 | −0.095 * | 0.092 * | −0.053 | −0.075 | 0.173 ** |

| company size | 0.077 * | −0.177 ** | 0.071 | −0.049 | −0.132 ** | 0.366 ** |

| Commitment | Support | Neutral | Disagree | Against | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Promotion of gender equality | 49.5 | 34.0 | 11.9 | 1.0 | 3.5 |

| Prevention of sexual harassment | 61.7 | 33.0 | 4.3 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Prevention of intimate partner violence against women | 57.5 | 35.2 | 5.8 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| TA | SA | A | D | SD | TD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive denial | ||||||

| Discrimination against women does not exist today since we are all equal before the law. Now men and women have the same opportunities. | 20.5 | 8.9 | 17.9 | 36.3 | 7.9 | 8.5 |

| Violence against women should not be discussed, but only partner violence, since men are also attacked. | 21.2 | 11 | 38.2 | 18.1 | 4.9 | 6.6 |

| You cannot talk about gender equality if we only talk about “violence against women”. We should only talk about family or partner violence. | 22.8 | 14.1 | 35.6 | 17.6 | 3.4 | 6.5 |

| Avoidance of responsibility | ||||||

| Companies are not responsible for the existence of these problems of violence. It is the government’s responsibility. | 5.7 | 3.9 | 15.7 | 49.4 | 12.1 | 13.3 |

| Businesses comply with all laws to prevent sexual harassment or gender discrimination. They should not be asked for more. | 5.3 | 5.2 | 20.4 | 50.7 | 9.1 | 9.4 |

| Strategic disarmament | ||||||

| There are more important priorities in the company than being concerned about some isolated cases of discrimination or gender violence. | 3.9 | 3.3 | 11.5 | 44.7 | 15.8 | 20.9 |

| I think that training/regulations on discrimination or gender violence are not very useful in companies | 3.6 | 3.4 | 17.6 | 43.8 | 15.1 | 16.5 |

| We have tried to support proposals in favor of women, but many do not make sense or are unsustainable. | 4.0 | 7.4 | 27.5 | 41.7 | 9.5 | 9.8 |

| Defensive disapproval | ||||||

| Talking too much about women demoralizes men at work. They have become “the bad guys in the movie” | 4.9 | 5.2 | 19.3 | 48.2 | 9.5 | 12.8 |

| Now, everything is women, violence, and discrimination. I think there is an exaggeration. It must find a balance. | 8.5 | 7.7 | 34.2 | 31.5 | 9.2 | 8.9 |

| Many gender equality policies have hidden interests. It’s too biased. I distrust them | 8.3 | 7.3 | 34.6 | 34 | 7.4 | 8.3 |

| Gender Barriers (Biases) | Men | Both | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulties getting a job when they have young children | 0.8 | 9.5 | 89.7 |

| Sexual harassment at work | 0.3 | 9.1 | 90.6 |

| Suffer more workplace bullying | 0.6 | 16.8 | 82.6 |

| Suffer more domestic violence | 0.5 | 17.3 | 82.3 |

| Difficulties reconciling family and work life | 4.4 | 33.3 | 62.3 |

| Challenges in achieving high positions in companies | 3.6 | 37.2 | 59.2 |

| Discrimination at work | 1.4 | 40.5 | 58.2 |

| Difficulties getting promotions | 2.3 | 45.2 | 52.5 |

| Difficulties feeling safe at work | 3.3 | 47.4 | 49.3 |

| B | S.E. | Wald | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval (Exp(B)) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Gender bias | −1.998 | 0.371 | 28.947 | <0.001 *** | 0.065 | 0.281 |

| Irrational beliefs about sexual violence | −0.629 | 0.712 | 0.782 | 0.377 | 0.132 | 2.150 |

| SDG-5 importance | 0.658 | 0.186 | 12.545 | <0.001 *** | 1.342 | 2.780 |

| Implicit resistance | −0.016 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.898 | 0.795 | 1.299 |

| Commitment to prevent | −0.230 | 0.153 | 2.248 | 0.134 | 0.589 | 1.073 |

| Standardized Effect (Beta) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | Total | |

| Implicit resistance | |||

| Gender bias | 0.315 *** | − | 0.315 *** |

| Irrational beliefs about sexual violence | 0.306 *** | − | 0.306 *** |

| SDG-5 importance | −0.125 *** | − | −0.125 *** |

| Sex (women) | −0.012 | − | −0.012 |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.001 | |

| Educational level | −0.047 | − | −0.047 |

| Company size | −0.107 ** | − | −0.107 ** |

| Prevention commitment | |||

| Implicit resistance | −0.174 * | − | −0.174 *** |

| Gender bias | −0.156 *** | −0.054 *** | −0.210 *** |

| Irrational beliefs about sexual violence | −0.071 | −0.053 *** | −0.124 ** |

| SDG-5 importance | 0.187 *** | 0.021 ** | 0.209 *** |

| Sex (women) | −0.039 | 0.002 | −0.036 |

| Age | −0.052 | −0.001 | −0.052 |

| Educational level | 0.109 ** | 0.008 | 0.117 ** |

| Company size | 0.016 | 0.018 * | 0.030 |

| Prevention actions in the company | |||

| Implicit resistance | −0.207 *** | −0.018 * | −0.226 *** |

| Prevention commitment | 0.105 ** | − | 0.105 ** |

| Gender bias | 0.024 | −0.087 *** | −0.062 |

| Irrational beliefs about sexual violence | −0.039 | −0.076 *** | −0.116 ** |

| SDG-5 importance | −0.022 | 0.048 *** | 0.070 |

| Sex (women) | −0.051 | −0.001 | −0.052 |

| Age | −0.058 | −0.005 | −0.064 |

| Educational level | 0.021 | 0.022 * | 0.044 |

| Company size | 0.294 *** | 0.022 * | 0.317 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vara-Horna, A.A.; Asencios-Gonzalez, Z.B.; Quipuzco-Chicata, L.; Díaz-Rosillo, A. Are Companies Committed to Preventing Gender Violence against Women? The Role of the Manager’s Implicit Resistance. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010012

Vara-Horna AA, Asencios-Gonzalez ZB, Quipuzco-Chicata L, Díaz-Rosillo A. Are Companies Committed to Preventing Gender Violence against Women? The Role of the Manager’s Implicit Resistance. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleVara-Horna, Arístides A., Zaida B. Asencios-Gonzalez, Liliana Quipuzco-Chicata, and Alberto Díaz-Rosillo. 2023. "Are Companies Committed to Preventing Gender Violence against Women? The Role of the Manager’s Implicit Resistance" Social Sciences 12, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010012

APA StyleVara-Horna, A. A., Asencios-Gonzalez, Z. B., Quipuzco-Chicata, L., & Díaz-Rosillo, A. (2023). Are Companies Committed to Preventing Gender Violence against Women? The Role of the Manager’s Implicit Resistance. Social Sciences, 12(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12010012