Abstract

This paper analyzes how the City of Montréal employed tools of urban planning—including a district plan, street redesign, rezoning, selective public consultation, expropriation, policing and surveillance—to spatially banish sex work from its historic district, using the red light symbol as a branding strategy. This coincided with a change in federal law (Bill C-36) and a policy shift to reposition sex workers as passive victims of sex trafficking. Using a case study design, this work explores the state’s refusal to recognize the agency of those engaged in embodied socio-economic exchanges and the safety and solidarity possible in public space. In interviews, sex workers described strategies of collective organizing, resistance and protest to hold the city accountable during this process of displacement. We consider how urban planning might support sex work, sex workers and economic autonomy.

1. Introduction

In this special issue on the health, safety and rights of sex workers, we offer this study on how urban planning tools were used to spatially banish sex workers from public space. Historically, Red Light Districts were tolerated as areas for sex work. In Montréal, authorities tended to overlook brothels, bawdy houses and cabaret venues near the intersections of Boulevard Saint-Laurent and Rue Sainte-Catherine by the port, especially during prohibition in the United States (1920–1933). This illegality differed from Red Light Districts in Belgium and the Netherlands, where sex work is legal and regulated, albeit confined (Loopmans and van Den Broeck 2011; Weitzer 2014; Weitzer and Boels 2015). However, as downtowns have become the focus of redevelopment pressure in many cities internationally, new approaches to the governance and spatial management of sex work put pressure on these semi-informal economies, leading to the dispersal of sex work to city peripheries or into more limited confinement. In this paper, we consider the spatial dispersal of sex work through urban planning in the case of Montréal’s Quartier des spectacles.

1.1. Sex Work and Gentrification

In an attempt to separate ‘normal’ sexual life, such as reproductive sex within a hetero-family unit, from other forms of ‘deviant’ sex, including those involving non-reproductive economic exchanges, sex work has been the target of spatial strategies and regulation, through banishment or confinement into specific city districts. Urban inner cities have been shaped into spaces of hard-fought sanctuary and freedom for a number of stigmatized groups, including Black and racialized communities, immigrant communities, communities of the unhoused such as in Los Angeles’ ‘skid row’, gay villages, and Red Light Districts. The spatial strategies that cities use to criminalize homelessness and sex work are similar to tactics of spatial segregation of other marginalized communities (e.g., Hubbard 2016). These include zoning, bylaw enforcement and policing, and cycles of economic disinvestment and reinvestment (e.g., Maginn and Steinmetz 2014). As urban investments shifted and cities remade downtowns for public-private growth coalitions, they used a variety of tactics to push out existing economies and communities. In Amsterdam, for example, re-regulation of the Red Light District shrank its boundaries and pushed some sex work into informal and online spaces (Aalbers and Deinema 2012). While gentrification can improve the safety and social supports of street-based sex workers when it adds environmental upgrades and community support (Oselin et al. 2022), it can also drive sex workers from the city center to more peripheral and dangerous areas, subjecting them to greater risk of violence and victimization from both police and clients (Lyons et al. 2017; Ross 2010). Urban planners and city governments collaborate to make sex-related businesses less visible, and clear the way for redevelopment through enforcement or relocation (Crofts et al. 2013). This urban invisibilization is noted by Viviane Namaste, Professor at the Simone de Beauvoir Institute at Concordia University, who has written and enacted art about the relationship between Montréal’s Quartier des spectacles and the quartier’s displacement of marginalized groups (Namaste 2014).

1.2. Transforming Montréal’s Red Light District to the Quartier des Spectacles

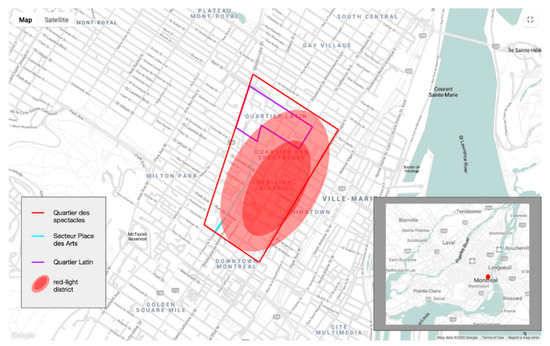

Montréal’s former Red Light District was located downtown and was the location of commercial sex activity for over a century. This included brothels, strip clubs, massage parlours, burlesque shows and cabarets, in many different and evolving venues, as well as street-based sex work. A ‘Red Light District’ is an urban area where there is a concentration of commercial sex or erotic activities available, and the conglomeration of sex work into one district has been a common urban trend since the nineteenth century (Herland 2005; van Liempt and Chimienti 2017). The Red Light District in Montréal has historically been centered downtown near the Port of Montréal, where military barracks were positioned and where soldiers were shipped off to war throughout the City’s history (Tremblay 2020). While Montréal’s Red Light District boundaries have varied over time, they have generally been centered on the intersection of Boulevard Saint-Laurent and Rue Sainte-Catherine in the borough of Ville-Marie (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A map of the Quartier des spectacles boundaries, including the Secteur Place des Arts and Quartier Latin poles, and the Red Light District in Montréal.

Throughout history, Montréal’s sex industry fell under fluctuating intensities of regulation (Mortimer 2009). The idea of morality has strongly guided the regulation of sex work and keeping the public ‘safe’ from vices like sex has been a primary motivator for arrests of sex workers and clients (Mortimer 2009; Namaste 1996, 2000; Weintraub 2004). In the past, very clear differential spatial enforcement about where commercial sex could take place was more prominent, with arrests for sex work happening in middle-class neighbourhoods at a much higher rate compared to arrests at businesses run within the Red Light District (Mortimer 2009). Regulating the activities in the Red Light District was more sporadic. Invisible contracts between brothel owners, mafia, police and politicians were well known and illegal behavior was sometimes mutually tolerated (Weintraub 2004). These processes worked, over time, to continue spatializing sex work into the Red Light District, versus dispersing it throughout the city, by fostering a space where actors knew commercial sex was more of a secure option because of lighter enactment of regulations and policing. When arbitrary loitering and vagrancy laws gave police sweeping powers to arrest those who did not conform to social norms (used more frequently against street-based sex workers and queers), brothels and bars became safer places for sex workers to find work (Lavorato 2014; Namaste 1996).

1.3. Legal Tools

To elucidate how sex work has been conceived of within contemporary urban planning in Montréal it is important to understand how the regulations of sex work operate in conjunction with local anti-sex trafficking policy and judicial influences. Then, opportunities to address the many challenges surrounding urban planning and sex work can be considered.

In 1985, Canada enacted Bill C-49, which criminalized street-level solicitation by both the client and the sex worker. This harsh approach made anyone who stopped a car, impeded pedestrian or vehicular traffic or attempted to communicate with any person in a public place or a place open to public view, for the purpose of engaging in sexual services, guilty and punishable by prosecution. This remained law until it was replaced in 2014 by Bill C-36, which defines sex work as inherently exploitative and bans negotiating to buy sexual services through criminalizing clients, venues and platforms (Government of Canada 2018). This shifted the criminalization of sex work, without achieving decriminalization. This shift in criminalization was prompted by the Bedford Decision, where three sex workers challenged the government’s prohibition on prostitution in venues, such as bawdy houses, emphasizing that these venues could provide safer spaces for sex work by allowing safety measures such as screening clients and hiring security to protect sex workers from violence (Canada v. Bedford 2013). While removing the ban on prostitution, Bill C-36 simultaneously shifted criminalization to venues. Advertising the sale of another person’s sexual services is also illegal and criminalizes the locations that advertise any offer of sexual services for sale, such as erotic massage parlours or strip clubs. Bill C-36 also criminalizes owning, managing, or working for a commercial enterprise, such as a strip club, massage parlour, or escort agency, if it is known that sexual services are purchased there. This policy increases the potential for harm against sex workers by making spaces criminally liable and thus reducing the opportunity for sex workers to have third party supporters, reduces sex workers’ capacities to gain a livelihood, and reduces opportunity for sex workers to be able to work inside venues, which is often safer than street-based sex work (Government of Canada 2014).

Outside of the legislation affecting sex workers directly, there is also legislation regarding sex trafficking that is sometimes used as a cause for jurisdiction over sex work and sex establishments, even though those who do sex work and those who are victims of sex trafficking are not entirely the same populations (Chapman-Schmidt 2019; Hubbard et al. 2013). A crucial difference is that people who are trafficked for profit are, by definition, not participating voluntarily, but are being forced into inherently exploitative bodily work, which can result in the trauma of sexual assault and other forms of violence. Sex trafficking falls under the umbrella of human trafficking and involves forced participation in commercial sex acts (Government of Canada 2021). One challenge is that when anti-trafficking frameworks are broadly applied, it can re-criminalize all sex work without improving safety or agency, driving sex work back into an underground economy which can exacerbate vulnerability and increase danger and risk (Davies 2015; Desyllas 2007; Spanger 2011).

Claims against sex work in the name of reducing sex trafficking often create “networked ignorance” that fails to consider the nuances of the sex industry (Mendel and Sharapov 2016). Sex workers are often put at greater risk when human trafficking laws do not independently consider non-trafficked sex work (Chapman-Schmidt 2019). When policy ascribes a judgement of greater exploitation, the harms faced by sex workers can be exacerbated (Browne et al. 2018; Hubbard et al. 2013; Hyatt 2013). This is because if all sex work is vulnerable to anti-sex trafficking enforcement, then consensual sex work must go further into hiding, which makes sex workers more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse, along with making livelihood less accessible. Anti-trafficking policies would be more effective if they considered systemic injustices rather than focusing on immorality or criminality. As Davies asserts, an “…exclusive focus on criminal law fosters the belief that justice, safety, and well-being are ensured only if individual deviants are apprehended and punished” thus, “…people marginalized by systemic racism, nationalism, heterosexism and cisgender privilege warrants skepticism about who will be targeted as deviant” (Davies 2015, p. 87).

These laws and policies often work subversively with land-use regulations to silently exclude certain groups of people from public spaces. It is not surprising that urban planning is, thus, intricately linked with sex work, and more specifically the regulation of sex work, as urban planning is often expected to provide insight into how we ‘ought’ to spatially organize communities (Barnett 2009; Krieger 2009).

1.4. Urban Planning Tools

The actual regulations and urban planning tools that contribute to the spatial organization of communities include municipal bylaws related to land-use regulations, zoning protocols, and nuisance laws. These urban planning tools, working in conjunction with the laws and policies described above have power over sex workers as a group, ultimately disempowering their autonomy through spatial regulation. A case study of Montréal’s Quartier des spectacles will be used to elucidate these issues in the next section; thus, the urban planning tools and their influence on sex work that are described below relate specifically to the municipality of Montréal.

At the municipal level, bylaws surrounding sex work are a marker of how a city defines the limits of acceptable sexuality through the symbolic ordering of space. A common way that this control takes form is through land-use regulation of the commercial sex industry and spatial policies surrounding street-based sex work. Spatial regulations on commercial sex often proceed from the assumption that sex premises promote crime, nuisance, and public disorder (Hubbard et al. 2013). Further, zoning protocols allow urban planners to have a decision-making tool that can directly affect urban landscapes (Barnett 2009; Krieger 2009). This is not a new process as urban beautification has historically been seen as a way to actively improve the moral and social character of a city’s citizens (Sitte 1889). In this way, bylaws and zoning regulations are tools that inherently act, consciously and unconsciously, to reflect and enforce a moral code.

Land-use planning is based on the premise that land-use regulations do not act upon people, but upon urban form (Blomley 2017). However, historically it is evident that this is not the case (Blomley 2017; Gupta 2015; Valverde 2012). Under the pretext of urban form, land-use regulations can allow decision-makers to avoid or evade issues related to people and shape the city through exclusionary acts. Commercial sex businesses are often pushed down the land-use hierarchy into less ‘desirable’ areas, either by banning sex-work and sex work-adjacent businesses such as massage parlors or strip clubs outright or by mandating separation distances between them to limit clustering. This same process echoes the way that exclusionary residential zoning has been used for racial and class-based segregation that enables differential exposures to pollution and access to amenities such as green space, resulting in group-based vulnerability to violence and premature death (Gilmore 2007; Johnston et al. 2002; Waldron 2018).

In areas that are being ‘cleaned up’ for redevelopment, existing spatial rights can be phased out. This means that cities may change the zoning of an area, where the new zoning regulations make any erotic establishments in the area a ‘non-conforming use’. A legal non-conforming use “…occurs when the use of one’s land, building or structure is not permitted by the current zoning by-law, but was permitted by a previous by-law” (Unified/LLP 2022, para. 1). To appease anyone countering the zoning change, this process may do a ‘grandfathering-in’ of current establishments that are non-conforming, where they may continue to do business in that area under their acquired rights. However, if the establishment changes owners or use, then their acquired rights may be lost (Saint-Laurent Montréal 2020). One recourse for an erotic business is to apply for rezoning themselves (essentially, an exemption) but this is a substantial financial process with no guarantee of a successful outcome, costing anywhere between $100,000 and $250,000 (Hayes 2018). Additionally, in the Charter of the Ville de Montréal, section 65(1) allows the City to impose arbitrary regulations to divide its territory into specific vocation zones and to limit the maximum number of places intended for identical uses in each zone (Gouvernement du Québec 2020). Thus, the visibility and non-visibility of the sex industry are dependent on the regulations adopted at all levels of government.

These regulations play a decisive role in the spatial registration of places associated with the sex industry. A less covert but more restrictive example is the zoning in Montréal West which prohibits any establishments of an erotic nature over its entire territory (APUR Urbanistes—Conseils 2010). However, even areas zoned specifically for commercial sex or eroticism can be subject to intensified regulation. For example, in the suburb of Laval, a maximum of five erotic businesses are allowed in an even smaller territory (Enos 2018).

Nuisance laws are another method of moral regulation. Nuisance laws are meant to protect people from things that are offensive or dangerous and interfere with their enjoyment of their activities or property (Nussbaum 2010). Commercial sex establishments are often deemed a public nuisance because they are considered a danger to the public by promoting ‘high risk sexual activity’ and affecting the general health and moral welfare of society (Davies 2015; Nussbaum 2010). However, much of the perceived nuisance from sex work or sex work premises is confined to those engaging directly in sexual activities that are both consensual and conducted in private (Frank 2019). In addition, research has demonstrated that public health issues faced in sex establishments are no more prevalent than in other spaces where private sexual experiences occur (Frank 2019).

Eradicating public disorder or ‘nuisances’ by regulating those who are socially profiled as ‘disordered people’ also occurs and is often based on moralistic codes rather than actual danger or disorder (Davies 2015). Arguments tend to centre “…concern for the health and safety of ‘prostituted persons’ as well as threats to the safety of communities and children” (Davies 2015, p. 86). Laws and city-based regulations often cite morals as precedent. However, Nussbaum (2010) suggests that constitutional law that does this is based on beliefs rather than legitimate harm and is thus rooted in ‘disgust’—which is a feeling that does not inherently provide moral insight. In law and urban planning, nuisance is cited as a legitimate cause to enact regulation. However, the logical basis of nuisance can be difficult to determine and often works subversively to segregate or discriminate against typically oppressed groups of people while simultaneously failing to protect the public in a substantive way (Nussbaum 2010).

Another way that urban regulations marginalize sex workers is through a process where urban planning is considered part of ‘police power’, where planners and policymakers enact moral codes, and police enforce them (Stein 2019; Valiante 2015). In this situation, urban planning works alongside surveillance and policing to push sex work out of certain geographic areas of a city that have been identified for reinvestment, by displacing the existing economic activity, notably in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, and Amsterdam and Zurich’s city centers (Lyons et al. 2017; Ross 2010; van Liempt and Chimienti 2017). To further elucidate how urban planning contributes to the ongoing oppression of sex workers in society we looked to Montréal’s Quartier des spectacles as a case study.

2. Methods

Using an exploratory case study methodology (Yin 1988), data collection included two elements: a policy analysis of relevant media and urban planning documents, and semi-structured interviews with those in the sex work industry. The policy review was used to trace the urban planning processes and tools that were employed during the redevelopment of the Quartier des spectacles. Interviews offered insight into collective organizing and strategies used by sex workers to resist displacement and to engage with the planning process. McGill University Research Ethics Board (REB-1) reviewed and approved this project by delegated review in accordance with the requirements of the McGill University Policy on the Ethical Conduct of Research Involving Human Participants and the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (REB File #: 19-12-008). Data was collected between October 2019 and May 2020.

Members of the research team have lived experience in sex work, urban planning and social work. The authors encompass several other identities that aid in their understanding of these topics as well, including intersections with feminized, queer, trans and disabled world views. This research was conducted through their own lenses of privilege and oppression.

2.1. Policy Analysis

A range of strategies were used to identify relevant archival and contemporary policies, research, and media reports. Keyword searches were conducted of the following sources: the Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ) online archives of digitized historic news articles and periodicals, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, the City of Montréal website, the City of Montréal Master Plan, and the City of Montréal’s Programme particulier d’urbanismes (PPUs), using terms such as “Quartier des spectacles“, “sex work“, “Red Light”, “revitalization”, and “gentrification”, in both French and English. The same terms were also used to search various online forums and websites including the Save the Main Facebook page, Stella l’amie de Maimie website and online publications, and Google. Hard copies of policy publications and community reports from Stella l’amie de Maimie were also consulted. In-depth exploration of Quartier des spectacles-related websites and policy documents produced additional references.

2.2. Interviews

A total of 26 sex work-related groups or individuals were originally contacted to request participation. Groups and individuals were found through online research, personal networks, and snowballing recommendations. Potential participants were emailed an interview request in both French and English, outlining the research parameters. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with three current or former sex workers who are active in community organizing and are participant-witnesses to the transformation of the district. Interview questions focused on the respondents’ perceptions about the history of the Red Light District and subsequent revitalization of the area, the creation of the Quartier des spectacles and the changing landscape, the spatiality of sex work over time in Montréal and any personal stories to do with sex work in Montréal or urban planning processes in the Quartier des spectacles.

Interviews were carried out in participants’ personal offices, over video messaging or in a café. The researcher took notes throughout the interview and interviews were voice recorded with written consent. Further, participants’ biographies were verbally agreed on at the time of the interview and a written copy was then confirmed by the participant again via e-mail (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Key Informant Interviews.

We also attempted to interview urban planners about the transformation of the Quartier des spectacles, emailing requests in both French and English to multiple professionals who worked at the City of Montréal on the district plan (PPU) and with the Quartier des Spectacles Partnership, the non-profit agency created by the City of Montréal to enact the redevelopment, rebranding and redesign of the Quartier. A total of 30 urban planning related groups or individuals were contacted via email, all with follow up emails a week later; 23 did not respond, 6 responded and were unable to assist. One respondent, Dr. Nik Luka, advised on local planning processes and shared his knowledge of the redevelopment of the Quartier des spectacles.

2.3. Research Limitations

In order to promote increased transparency in research, the authors believe that it is important to note some challenges encountered in doing this work. The primary obstacle relates to whose perspectives and voices are reflected in the data, including existing policies, media, and key informant interviews. As will be demonstrated throughout the case study, urban planning documents that were examined as part of this project, often lacked perspectives from multiple voices, particularly those of people involved in sex work. In addition, sex work was rarely discussed or even alluded to in official documents. This is important to note, especially in conjunction with public servants’ lack of participation in interviews, as it may reflect an unwillingness on the part of municipal personnel to discuss certain topics, such as sex work, in relation to the City’s actions. Though City of Montréal and other City-related personnel and public servants were invited to participate in this research, none agreed. Together, these factors point to the City’s erasure of sex work through official practices of disconnection or distancing. Despite this, interview participants include three people with sex work experience and specific, local knowledge of sex work history and community organizing in this part of Montréal. While the number of key informants was small, the information participants shared has been used to add context and to triangulate data from the policy documents and archival materials included in this case study.

3. Key Themes

Based on the policy analysis and key informant interviews, the following six key themes were identified: (1) targeted transformation, (2) spatial banishment, (3) policing, (4) gentrification, (5) red light branding and (6) exclusion. Each is discussed below, integrating materials from both aspects of the data collection process.

3.1. Targeted Transformation

The Montréal Summit (2002) and the consultation process that led to it, asserted the need for an ambitious cultural policy at the municipal level (Hadler 2014). At the Summit, culture was positioned as a key economic development tool for Montréal (Quartier des Spectacles Partnership 2020). Leaders of the sector crafted the Quartier des spectacles concept as a way to energize Montréal’s cultural scene (Quartier des Spectacles Partnership 2020). Following this, the City of Montréal formed the Quartier des Spectacles Partnership in 2003, bringing together an array of key stakeholders. This non-profit organization was mandated by the City to identify a vision and plan for the future of the Quartier des spectacles.

The development of a unique and encompassing identity for the Quartier des spectacles was a key goal of the project. Rebranding the area was focused on building from the district’s existing cultural assets to create a new, attractive image. Claude Deschênes, author of the book entitled Tous pour un Quartier des spectacles Montréal notes in an interview with Couture (2018) that “The municipal government was pulling in the same direction as the provincial government of the day, which believed strongly in the idea of using culture as an engine for economic development.” (para. 4).

Over time, the Quartier des Spectacles Partnership’s governance shifted when the City took over its planning mandate. The City of Montréal decided to apply the same strategy to the Quartier des spectacles that it had successfully implemented in the newly redeveloped Quartier International, where a large-scale public-space improvement scheme was used to boost property values in the surrounding area and attract new real estate investments. The city chose to mandate Quartier International de Montréal (QIM), the non-profit organization in charge of the Quartier International project, to develop the Quartier des spectacles’ planning project in 2007 (Klein and Shearmur 2017; Ville de Montréal 2011). It was the QIM that mandated the private Daoust Lestage firm for the creation of a development vision (Klein and Shearmur 2017). This change meant that rather than maintaining overall planning responsibilities, the Quartier des Spectacles Partnership was now responsible for managing only the open, public spaces. Today, a key component of the Quartier des Spectacles Partnership is the organization and promotion of many of the cultural and public space events that take place in the area (Quartier des Spectacles Partnership 2022).

A major factor in pushing the Quartier des spectacles projects forward so efficiently was the creation of a PPU (‘Le Programme particulier d’urbanisme’—City of Montréal district plan). A PPU is a Quebec planning tool that allows municipalities to define specific planning goals and measures in a given territory. When a city creates a PPU, it allows a municipality to grant special attention to a specific sector and to guide that sector’s development by implementing fine-grained planning measures. PPUs provide an effective tool for rapid action since the process for adopting a PPU for a strategic district is faster and simpler than the standard process for making changes to the City’s Plan d’urbanisme, which is required by law if a municipality wants to introduce significant changes to existing planning regulations. Adopting a PPU, therefore, allows municipalities to avoid a long and complex process. However, PPUs leave less time for public consultations and thus a limited amount of time for a range of citizen voices to be heard. In the case of the Quartier des spectacles, while some smaller consultations were held, it was a very rapid process from vision to development. Fran notes that: “The city is responsible to make the environment safe for all of its people, even the people that are not considered citizen and this is the big problem. Who deserves to be called a citizen?”.

The 2007 PPU for the Quartier des spectacles project received the support of the federal and provincial governments, along with the City of Montréal (Ville de Montréal 2011). A specific PPU covering the Place des Arts sector was adopted in 2008 (Office de consultation publique de Montréal 2013). In 2011, the Ville-Marie borough began a PPU for the Quartier Latin section of the Quartier des spectacles (Office de consultation publique de Montréal 2013). Since then, many private and public spaces, as well as commercial and residential real estate projects, have been built, including several with a cultural focus. Notably absent in all these plans is any explicit acknowledgment of the site as a working Red Light District or consideration of the impacts of redevelopment on sex work.

3.2. Spatial Banishment

In 2007, the City succeeded in expropriating a building that housed a peep show and other adult businesses at the corner of Boulevard Saint-Laurent and Rue Sainte-Catherine (Global Site Plans—The Grid n.d.). Expropriation involves forcibly taking property from its owner for public use or benefit, as an action by the state or an authority (Tribunal Administratif du Québec 2005). The building was replaced by the 2-22, a $20 million cultural centre, developed by the Société de développement Angus (SDA) (Global Site Plans—The Grid n.d.). This was part of a project called the Quadrilatère Saint-Laurent. The Quadrilatère Saint-Laurent’s explicit goal was to carve out a space for a whole new demographic of consumers—a demographic that had higher socioeconomic status and would be able to participate in the Société de développement Angus’ more expensive complexes, thus explicitly increasing the gentrification of the area. This particular project is an example of the ways that the government was supporting and backing the transformation of the area.

Some businesses at the time attempted to resist further renewal and gentrification of the area, most prominently the additional expropriation of Café Cléopâtre in 2009, which fell within the Quadrilatère Saint-Laurent. Hosted in a building from the late 1800s, and a flagship strip club in Montréal since 1976, Café Cléopâtre has been threatened by different development projects over time. The 2009 expropriation attempt was cause for concern for many as Café Cléopâtre is important to the history of Montréal, especially LGBTQ+ people, where typically, since its opening in 1976, clientele for cisgender female strippers are welcome downstairs, and the upstairs hosts drag queen, trans, burlesque and LGBTQ+ parties and shows (Patriquin 2011). Due to Café Cléopâtre’s cultural importance, a group of show producers, venue owners, non-profit organizations, and concerned citizens banded together and started having meetings surrounding the expropriation of Café Cléopâtre, as well as the City’s expropriation of a row of historic venues along Boulevard Saint-Laurent (‘the Main’) in the Quartier. This group was called Save the Main.

Candyass, a member of Save the Main, discussed the strategies she carried out such as distributing petitions, going to question periods at City Hall and attending the Office de consultation publique de Montréal/The Montréal Public Consultation Office (OCPM) hearings. She described the circumstances as follows:

We would cram in to try and get a spot to ask a question because the developer was trying to fill up the hearings with people asking lighthearted questions, and so we created a visual and verbal stir with all our various questions and comments. We submitted memoires and reports, there was a fair amount of press on us internationally.

However, Candyass also explained that a key issue with the OCPM hearings was that they often happened after the beginning of a project, and “… unless you have a strong group of guerilla fighters to garner the press and battle it out in various forms…” you won’t be heard at all. Moreover, as the development pressure along the Lower Main was mounting, smaller businesses and venues ended up folding.

A representative for the SDA (Société de développement Angus, the developer of the 2-22), Geneviève Marsan, described the goals of the SDA’s project in an interview in 2011, saying, “We want to revitalize the Quartier. We don’t want strip clubs. They don’t fit in with [SDA’s] values. We certainly want to integrate commerce, but not exploitative commerce…” (Shoukri 2011, para. 7). In this statement, sex work is conceptualized as solely exploitative and illegitimate. Further, it underlines the ways sex work did not fit into the developer’s or the City’s vision for the district. Around the same time, the mayor vowed to pave the way for these developers as quickly as possible, saying “We’ve consulted everyone [about City projects] but we’re not going to stop because a minority says it might affect certain things that are important to Montréal….” (Harper 2009).

The public consultation documents produced by the OCPM for the Quadrilatère Saint-Laurent in 2009 note Save the Main’s influence and affirm that the new buildings proposed surrounding Café Cléopâtre would not fit the existing aesthetics of the street, including the current building heights (Office de Consultation Publique de Montréal 2009). Upzoning and the imposition of higher property taxes were used to pressure existing venues and businesses to fold. Candyass explains, “… delays are important, the more you can make developers spend money on nothing, it frustrates them and manages to reduce the projects, which is what we were relatively successful at doing…”. Eventually, the City administration dropped expropriation proceedings against Café Cléopâtre. However, the rest of the street was not spared from demolition. Between the Monument-National and Café Cléopâtre, and from the other side of Café Cléopâtre to Rue Sainte-Catherine, the only buildings not demolished were the Monument-National and Café Cléopâtre.

Café Cléopâtre has continued to be under threat. Even five years ago there were still conversations about the City wanting to shut it down. Interview participant Maux suggested that this is particularly concerning as Café Cléopâtre has always been known as a safer place for trans sex workers to go, as well as employing a lot of trans women as bartenders and staff. As the street continues to change, venues and safe places for sex work continue to close, with little to no affordable spaces for less expensive entertainment options. Candyass explained that each closure offers “… just another tombstone littering the graveyard of the Quartier des spectacles.”

Save the Main organized a funeral for the street when the final orders for demolition went through for the various buildings adjacent to Café Cléopâtre. As described by Candyass:

We did a funeral of the street in memory of these buildings and the people and the life, that intangible ephemeral aspect, everyone came out in their finest funeral garb, we had two coffins rolling down the street, and a mournful tuba player and people gave eulogies of growing up on the street…. People realized the street is changing, we can’t necessarily stop it, but how can you at least keep the best of the old, or recognize it, support people, support the more marginalized.

3.3. Policing

The urban design transformation of the Red Light District into the Quartier des spectacles thickened the regulatory management regime. Changes to the physical urban design were used as a way of controlling infrastructure to limit certain kinds of activity. More specifically, shutting off certain streets to cars and creating pedestrian-only zones prevented sex workers from public access to customers in cars. These actions were combined with 315 new surveillance cameras installed in the Quartier in 2018 to further monitor activities in public spaces (Normandin 2018).

Michaud O’Grady (2015) explains how the creation of the Quartier des spectacles corresponded with an increase in repressive police tactics downtown. The lead-up to the development of the Quartier des spectacles contributed to many commercial venue closures by either expropriation or voluntary departures due to the growing pressure of rising municipal taxes and police tactics, particularly the ‘Morality, Alcohol, and Narcotics Section’ of the Montréal Police Service (SPVM) (Michaud O’Grady 2015). Michaud O’Grady explains:

While the SPVM was in some cases directly responsible for the closures and removal of specific forms of cultural expression downtown, in the majority of instances the closures were the result of a complex interplay of development, municipal bylaw enforcement, and high-income residential development. The role of the police in the closure of venues and in laying the infrastructural groundwork for the Quartier des spectacles was embedded within a particular trajectory of shifts in policing practice throughout the 1990s and 2000s… It is this trajectory that in many ways consolidated the transformation of street-level social relations and the displacement of street culture.(Michaud O’Grady 2015, pp. 77–78)

The disregard for, as well as participation in, violence and assault against sexual and gender minorities and sex workers by police has been documented and remains an ongoing concern (CTV Montréal 2019; Namaste 1996). In October 2001, local non-profit organization Stella l’amie de Maimie was supporting sex workers in a series of lawsuits involving loitering, jaywalking and drug use, claiming discrimination in the ways these regulations were applied to sex workers (The Global Network of Sex Work Projects 2015). Unfortunately, this collective action coincided with an intensification of police activity. The SPVM was instructed to increase arrests under section 213 of the Canadian Criminal Solicitation Code (section 213 referred to solicitation in public, currently struck down by Bill C-36) (Government of Canada 2020). As a result, Stella l’amie de Maimie reports that solicitation arrests (when solicitation was still illegal for sex workers) went from 38 in 2001, to 825 in 2004 (Crago and Clamen 2013; Stella l’amie de Maimie 2012). If a sex worker was found to be in violation of section 213, they often also received a Quadrilateral Restraining Order. A Quadrilateral Restraining Order is a spatial regulation that restricts the recipient from entering certain neighbourhoods—not only for solicitation but for any reason. This is part of a larger trend of red-zoning, or area restriction sentencing, seen in other cities in Canada (MacDonald 2012; Sylvestre et al. 2015).

A very real danger with a Quadrilateral Restraining Order is that sex workers are often residents of the areas that they become prohibited from entering, yet they still need to access resources and services in those areas, such as their children’s schools, grocery stores, support groups, etc. (Butler Burke 2016; Stella l’amie de Maimie 2008). Stella l’amie de Maimie (2008) goes on to state that “an order typically includes the areas between Rue Jeanne-Mance and continues to Rue Viau, as well as Boulevard René-Lévesque to Rue Sherbrooke. At times, a zoning restriction is given to a sex worker for the entire island of Montréal!” (p. 3). This results in sex workers being isolated or breaking their restraining order conditions so that they can continue to live and, thus, the solicitation sentence that a sex worker may have received is intensified by a zoning restriction. The very nature of this spatial regulation innately results in recidivisms.

There have been attempts at collaboration between sex workers and police over the years. A clear example was a pilot project in 1999, where the City Committee on Street Prostitution:

… propose[d] a suspension of enforcement of federal sex work laws or ‘dejudiciarize’ sex work (Sansfacon, 1999). A pilot project was initiated in the areas with the largest concentration of street prostitution. Instead of repressing sex work, a community worker and police officer would respond to complaints from residents, including sex workers, mediate tensions due to disturbances, and take action against violence. If successful, the pilot project would be extended to the entire city.(Crago and Clamen 2013, p. 156)

Unfortunately, due to violent backlash from the public, this pilot project was shut down, and instigated additional crackdowns with police arresting those who buy sex in the area, again causing greater issues for workers themselves through lack of clientele and increased visibility (Crago and Clamen 2013).

3.4. Gentrification

Efforts to ‘clean up’ a city to make it more alluring for tourists are often an essential aspect in the revitalization of a city’s ‘brand’ and are, simultaneously, key aspects of gentrification (Bélanger 2012). Montréal’s Quartier des spectacles is first and foremost a space of cultural consumption, where the rise in property values in the area has displaced much of the original community. The Table de concertation du faubourg Saint-Laurent (2017) states that there has been a 10.8% increase in property values per year since 2004 and that as a result, the proportion of affordable housing is decreasing. This fact is chorused by Candyass who states that the district:

… is quite dead now, it’s just walls and walls of condos that don’t have life, there is no face to condos compared to triplexes or duplexes …. a new condo building that went up, right across is a green space where they cut down many cherry trees so that festivals, like the heavy metal festival, can happen there. But nobody in a condo wants to be across from that, so that is going to be nothing other than an Airbnb because it’s not liveable.

She goes on to explain that because many of the hotels are gone (including the siesta rates that allowed short-term hotel use) and room and board options do not exist downtown anymore, pricier Airbnb’s are the only alternative for sex workers to see clients in the area.

3.5. Red Light Branding

Despite ongoing criminalization and stigmatization, sex work has simultaneously played an important role in the Quartier des spectacles’ image, tourist industry, and economic development (Mortimer 2009). Fran explains:

The difference between now and 20 years ago, you cannot even compare, it has been asepticized. People go there because they have this aura of exotic or mystique. It’s this idea of ‘Oh I don’t want sex workers, but I want to know that this was a place where all these things were happening’.

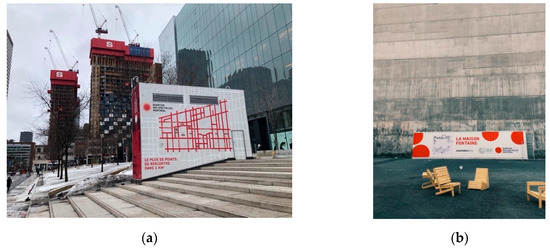

A key example of this can be seen in the Quartier des spectacles’ marketing scheme and lighting strategy which utilizes a lit red dot throughout the Quartier des spectacles as a visual identity—helping to re-vision the area as a “cultural epicenter” (Lam 2007). The idea of using light in the district’s brand was developed through the Quartier des Spectacles Partnership to connect the multiple project stakeholders around a common identity. This approach to lighting includes a series of video projections and architectural illuminations on the facades of several buildings in the Quartier des spectacles. The plan was implemented in two phases and was funded by the City of Montréal, the provincial government (for the first phase only), and the venues which were interested in participating. Examples of the lighting and branding strategy can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

(a,b) Examples of Quartier des spectacles red light symbol.

Figure 3.

Example of Quartier des spectacles streetscape.

Often, sex workers’ lives are “mined for creative potential” while simultaneously displaced by the middle-class (Tigchelaar 2019). As the lit red dot has clear links to the use of red lights in the historic Red Light District, this marketing technique appropriates the work of those who have since been pushed out of the area, namely, sex workers and sexual and gender minorities, for the sake of the festival and art tourism crowd. The ‘wink’ that this lighting strategy makes towards the area’s sex work history does not increase agency for or solidarity with sex workers still in the area today. Instead, it uses the ‘vice’ reputation of the area as a marketing tactic, transmuting it into a symbolic branding with a reference to sex work through the ‘red light’ motif, while simultaneously working through various tactics of policing, urban design, and redevelopment to banish real sex work from the area.

Tigchelaar (2019) discusses how this is a common trend in arts-based cities or districts, where the use of the historic Red Light ambiance and thematic elements are used to attract the tourist or middle-class crowd, but it is, simultaneously, a fake dialectic surrounding sex work. The irony of the Quartier des spectacles is that its branding hints at its past as the Red Light District—the ‘spectacles’ or shows of strip clubs, burlesque dancers, etc.—while shifting towards other kinds of entertainment, such as music shows, circus performances and so on. Montréal is part of the Global Cultural Districts Network because of the Quartier des spectacles (The Global Cultural Districts Network 2019) but the economic shifts from ‘vice’ city to ‘cultural’ city have included deliberate as well as inexplicit strategies to remove and displace sex work to sanitize the area for new real estate redevelopment and an economy built around real estate investment and bourgeoisie lifestyle.

There is an ongoing shift away from the area’s history towards increased aseptic spectacularization (Jacques 2011). One visible example is the changing dialogue surrounding the Quartier des spectacles symbolic lighting strategy. At the beginning of the project, the red lights were conceived as representative of the Red Light District. However, in current media and press releases, the lights are being presented as a ‘red carpet’ (Tourisme Montréal 2020) (Figure 4). The City of Montréal itself describes the lights as a red carpet into its cultural venues and touts the ambitious urban branding project’s creative potential, without any recognition of its history (Ville de Montréal 2020). This would seem to symbolize a shift by the City towards further erasure of the district’s historic past.

Figure 4.

Quartier des spectacles.

The district still uses and commodifies its Red Light history as a spectacle, but this does not contribute to the economy of sex workers—a circumstance echoed by each of the key informants in this study. All interview participants mentioned the pejorative yet normalizing gaze that the Quartier des spectacles project has had on sex work; sex work is simultaneously fetishized and sterilized. This area is becoming increasingly portrayed as “family friendly” and “middle class”. Participants noted that a once stigmatized but lively part of town has been sanitized and cleared for developer-friendly, state-sanctioned cultural entertainment. While sex work does still happen in the area, it has been pushed out of the public realm of the street and into the private realm of digital platforms and condo units.

3.6. Exclusion

A report on the sex industry in Quebec by a group concerned with sexual exploitation (Szczepanik et al. 2014) demonstrates that the majority of sex work in Montréal still takes place in the downtown Ville-Marie borough. The report suggests that there is likely a spatial shift from the Red Light District to more diffused and anonymous places. It is important to note, though, that this report does not account for all forms of sex work and is written from an abolitionist-based stance. Regardless, research for this case study corroborates this report’s suggestion that sex work is still occurring around the historic Red Light District, but generally dispersing.

When subject to banishment techniques through spatial regulation and policing, workers from Stella l’amie de Maimie noted that it does not mean sex workers will change jobs, “… it just forces them out of public view and into situations where they have to work from home or in unsafe areas.” (Enos 2018, para. 11). This contributes to the continued displacement of sex work to online environments or into private spaces such as Airbnb’s. For those who do street-based sex work, municipal forces have worked to push street-based sex work to places like Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, further east of downtown. As noted by Fran: “I mean you ask someone on the street and where do they go, where do you think, they don’t just disappear, they go somewhere else.”

Also highlighting the shift of the sex industry spatially towards Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, Fran mentions the general dangers of dispersing street-based sex work:

… if it’s in a strange neighbourhood and they’re alone it makes them more of a target. I’m not saying it was perfect in the Lower Main but it was definitely a better situation in terms of management, control, and regulation, compared to sending them all over the city without protection and having not only the law against them but the neighbourhood resident. They just added another dimension and layer of insecurity—isolation. So they double up the enemy, double what they have to fight. They made their life even more difficult.

Fran noted that demolishing the physical landscape of the Red Light District over time has had an impact on the agency and safety of sex workers. As such, displacing sex workers is an inherent act of violence against them. Based on her personal experience with sex work in the 1970s, she explains:

I was never afraid on Boulevard Saint-Laurent, I was very afraid in other parts of town—if you mind your own business on the Lower Main you didn’t get in any trouble. You get into trouble when you’re isolated. I think it was home for so many people, and a lot of people felt a lot more dangerous out of that community because then you become a target.

4. Discussion and Conclusions: Planning for Safer Sex Work

How could these findings be translated into urban planning practice? Since planners refused to be interviewed on this subject, our paper has focused on critiquing the ways in which urban planning is hostile to sex work. In this section, however, we shift to propose more generative responses to consider how the Quartier des spectacles could have been redesigned to preserve a place for street-level establishments, pickups and negotiations while maintaining public safety. Public space offers mutual safety in numbers as sex workers can watch out for each other. In order to consider the challenges of planning for safer sex work, planners would need to effectively understand the significance of sex workers in the urban fabric, and in our communities.

One can imagine how planners could better consider the impacts of urban design and redevelopment on sex workers. The public consultation process could invite sex worker organizations to the table with developers and negotiate the differences between concerns over public nuisance and the right to livelihood. Examples of these types of community-level collaborations including sex workers, local governments and residents have been seen in Aotearoa New Zealand (Neuwelt-Kearns et al. 2020). The loss of sex work venues through expropriation, gentrification and upzoning could be offset through social economy approaches such as commercial land trusts and worker co-ops, which are being used in other cities to mitigate displacement of existing communities and economies (Calkins et al. 2014; International Labour Organization 2020).

Creative urban design approaches could also consider how to facilitate street-level solicitation and discrete car-based pickups and still accommodate pedestrians and cyclists. The large hard-surface plazas could be designed with less easily surveilled open space, with the addition of more trees and street furniture, and could host entertainment events such as music, festivals, spectacles and public revelry without banishing sex work. Approaches to policing could focus on public safety rather than criminalization of sex work. Venues such as strip clubs, cabarets and massage parlours could be permitted in all commercial zones. Plans could include a section on existing economies and policies for keeping them in place while mitigating public concerns. Arms-length publicly funded agencies, such as the Quartier de spectacles Partnership, could prioritize existing community partners to counterbalance powerful developer interests. Montréal has a thriving social economy sector, which could be involved to preserve and redevelop affordable spaces for existing venues and businesses without displacement.

We should also note the multiple attempts that the sex worker community made to engage with the planning process in the Quartier. They successfully contested the expropriation of at least one beloved venue, Café Cléopâtre, and held a public march protest in the form of a funeral for the street. They organized as an interest group, Save the Main, in support of heritage protection in order to protect the existing venues. Moving online or moving to other neighbourhoods is an adaptive strategy of resistance to erasure. Without recognition and accountability by the City, the visibility and safety of sex workers is compromised.

The City of Montréal, including urban planners, law makers, and policy regulators, needs to acknowledge the responsibility it has in preventing the displacement of people into more vulnerable circumstances and spaces. A true inclusion of marginalized voices, like those of sex workers, in urban planning processes could work to promote equity and inclusivity in cities like Montréal.

Urban planning is meant to improve the quality of life for all, including marginalized groups. Marginalized groups have the right to speak for themselves and set their own agendas, which does not happen in many current policies, especially surrounding sex work (Desyllas 2007). Increased criminalization contributes to higher risk environments for sex workers. As noted by the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform (2014), “…the criminalization of sex work and the accompanying lack of respect for sex workers’ human rights forces sex workers to work in circumstances that diminish their control over their working conditions and leaves them without the protective benefit of labour or health standards” (p. 1). Sex workers employ a number of strategies of mutual aid and relationships with venues and platforms to secure their safety, from strolling together on streets to hiring security and screening clients in venues (Canada v. Bedford 2013; Oselin et al. 2022). Sex worker movements have been prominent in Canada over time and have demonstrated that sex workers are engaged and ready to offer support to policymakers and lawmakers so that sex work can be better understood and practiced with principles of safety and consent.

Sex workers and sex worker organizations have, for many years, criticized how the legal framework in Canada impedes their ability to self-organize (Tremblay 2020). Further, it is not uncommon for police records to be different from the lived experience of sex work or actual regulation of sex workers (Namaste 1996). Strategies of solidarity are often taken up by sex workers as a means to meet their basic needs and so the legitimacy of informal solidarity strategies must be considered in future urban policy making (Crago and Clamen 2013; Tremblay 2020).

In August 2016, Amnesty International released a policy that calls for decriminalization of sex work—while still maintaining its strong stance against human trafficking. It is a policy that has been supported by numerous other organizations that work for the rights of vulnerable populations, and, most importantly, this policy is supported by many involved in sex work (Albright and D’Adamo 2017). Full decriminalization of sex work on a broader scale can also help frame anti-trafficking policy in a more accurate and useful way to help victims of trafficking as well as ensure safer working conditions for non-trafficked sex workers (Davies 2015). This idea of offering equal respect and taking a humanistic approach to policy is summarized by Desyllas (2007) in the following quote: “Move away from a moral lens that stigmatizes and marginalizes people and move toward protecting workers from unsafe labour conditions.” (p. 73).

When society portrays sex workers as victims, it dismisses them as workers. The Canadian legal system does not consider sex work a legitimate source of income generation and in a market-dominated society, denial of access to the market threatens survival (Davies 2015; Tremblay 2020). Lee and Persson (2021) highlight the importance of differentiating between sex work and sex trafficking in policy development:

In certain illicit markets [such as sex work], part of the supply involves the use of, or threat of, violence to coerce the provision of the good or service in question. In such ‘semi-coerced’ markets, the regulatory objective is not to prohibit all trade, but to prevent coercion without infringing on voluntary exchange. Regulatory policy must therefore be evaluated along two dimensions: What is the impact of a policy on coercive activity? How much does the policy conflict with voluntary supply?(p. 31)

Instead, considering sex work within a labour rights framework would reduce harm to sex workers (Davies 2015).

Authentically partnering with invested communities has many benefits in facilitating the planning and execution of urban projects (Ross 2009). The more that planning practice centres and cares for all groups of people, the more urban cultures can change to respect the agency of all people. To honestly include sex work in planning, Stella l’amie de Maimie (2008) suggests that working groups could be created by the City to discuss issues related to sex work and judicialization. Further, they suggest creating a consultation group including community groups that work with sex workers could be a more efficient way of addressing this complex problem. The sex work community in Montréal has a long history of organizing, as well as producing research (Crago and Clamen 2013; Stella l’amie de Maimie 2012)—tapping into these community-led resources should be prioritized to center sex workers in discussions that pertain to their livelihood.

Lastly, as discussed earlier, the full decriminalization of sex work, including the decriminalization of clients and platforms or spaces that sex work occurs in, is integral to the safety and working conditions of sex workers. There is no conflict between decriminalizing sex work and protecting sex workers from exploitation and harm; in fact, they work more effectively together. A federal shift to the decriminalization of sex work would likely contribute to larger changes that would benefit sex work in all other spatial and regulatory policies. For instance, it would allow policies to use a labour rights lens when considering sex work, as discussed previously. This could then extend into concrete spatial policies, such as treating erotic establishments as part of any commercially zoned area without additional limits due to its erotic nature. Further, decriminalization would allow for a cultural rethinking of sex work and could reduce the instigation of all disgust-based or moralistic regulations. Instead, centering voices of systemically oppressed communities allows for an acceptance of their realities and reduction in stigmatization. This rethinking would allow for greater autonomy and thus greater safety and agency for sex workers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F., Z.M. and A.K.; methodology, R.F.; validation, R.F., Z.M. and A.K.; formal analysis, R.F.; investigation, R.F.; resources, R.F.; data curation, R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, R.F.; writing—review and editing, Z.M. and A.K.; supervision, Z.M. and A.K.; project administration, R.F.; funding acquisition, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for a CGS Graduate Award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The REB-1 reviewed and approved this project by delegated review in accordance with the requirements of the McGill University Policy on the Ethical Conduct of Research Involving Human Participants and the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans. REB File #: 19-12-008. Date of approval 9 January 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participant(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aalbers, Manuel B., and Michaël Deinema. 2012. Placing prostitution: The spatial sexual order of Amsterdam and its growth coalition. City 16: 129–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, Erin, and Kate D’Adamo. 2017. Decreasing human trafficking through sex work decriminalization. AMA Journal of Ethics 19: 122–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APUR Urbanistes—Conseils. 2010. Town of Montréal West By-Law No 2010-002. Montreal: APUR Urbanistes. Available online: https://Montréal-west.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2010-002-zoning-consolidated.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Barnett, Jonathan. 2009. The way we were, the way we are: The theory and practice of designing cities since 1956. In Urban Design. Edited by Alex Krieger and William S. Saunders. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger, Hélène. 2012. The meaning of the built environment during gentrification in Canada. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 27: 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomley, Nicholas. 2017. Land use, planning, and the “difficult character of property”. Planning Theory and Practice 18: 351–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Jennifer, Brian Coffey, Kay Cook, Sarah Meiklejohn, and Claire Palermo. 2018. A guide to policy analysis as a research method. Health Promotion International 34: 1032–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler Burke, Nora. 2016. Connecting the dots: National security, the crime-migration nexus, and trans women’s survival. In Trans Studies: The Challenge to Hetero/Homo Normativities. Edited by Yolanda Martínez-San Miguel and Sarah Tobias. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 113–21. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins, Andrew, Andrew Desmond, Jennifer Malley, Alexandra Wakeman Rouse, Lauren Smith, and Martha Sassorossi. 2014. Permanently Affordable Commercial Space: A Means of Preventing Business Displacement in Neighborhoods Facing Gentrification. Available online: https://tacklingcommercialgentrification.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/affordable-commercial-space-final-1-2.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Canada v. Bedford. 2013. Available online: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/13389/index.do (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform. 2014. Why Decriminalization Is Consistent with Public Health Goals. Available online: https://www.safersexwork.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WhyDecrimisConsistentwith.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Chapman-Schmidt, Ben. 2019. ‘Sex trafficking’ as epistemic violence. Anti-Trafficking Review 12: 172–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, Philippe. 2018. A New Book Tells the Story of the Quartier des Spectacles: Already 15 years! Quartier des spectacles Montréal. October 19. Available online: https://www.quartierdesspectacles.com/en/blog/763/a-new-book-tells-the-story-of-the-quartier-des-spectacles-already-15-years (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Crago, Anna-Louise, and Ienn Clamen. 2013. Né dans le Redlight: The sex workers’ movement in Montreal. In Selling Sex: Experience, Advocacy, and Research on Sex Work in Canada. Edited by Emily Van der Meulen, Elya M. Durisin and Victoria Love. Vancouver: UBC Press, pp. 161–78. [Google Scholar]

- Crofts, Penny, Phil Hubbard, and Jason Prior. 2013. Policing, planning and sex: Governing bodies, spatially. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 46: 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CTV Montréal. 2019. Sex Workers Criticize Police Action in Strip Clubs, Massage Parlours. CTV News Montréal. June 8. Available online: https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/sex-workers-criticize-police-action-in-strip-clubs-massage-parlours-1.4458145?cache=yesclipId104062 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Davies, Jacqueline M. 2015. The criminalization of sexual commerce in Canada: Context and concepts for critical analysis. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 24: 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desyllas, Moshoula Capous. 2007. A critique of the global trafficking discourse and U.S. policy. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 34: 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Enos, Elysha. 2018. Sex Workers Advocacy Group Demands Laval Retract New Restrictions. CBC News. January 18. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/laval-stella-massage-parlour-erotic-regulation-1.4497486 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Frank, Katherine. 2019. Rethinking risk, culture, and intervention in collective sex environments. Archives of Sexual Behavior 48: 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. 2007. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Global Site Plans—The Grid. n.d. Red Light Stops Revitalization of Montréal’s Red Light District. Smart Cities Dive. Available online: https://www.smartcitiesdive.com/ex/sustainablecitiescollective/Red Light-stops-revitalization-Montréal-s-Red Light-district/1019951/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Gouvernement du Québec. 2020. c-11.4—Charter of Ville de Montréal, Metropolis of Québec. Available online: http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cs/c-11.4 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Government of Canada. 2014. Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act. (Department of Justice archives). Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/annualstatutes/2014_25/page-1.html (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Government of Canada. 2018. Prostitution Criminal Law Reform: Bill C-36, the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act. (Department of Justice). Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/other-autre/c36fs_fi/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Government of Canada. 2020. Criminal Code: Version of section 213 from 2003-01-01 to 2014-12-05; Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- Government of Canada. 2021. Strengthening Human Trafficking Laws; Ottawa: Department of Justice Canada. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/pl/shtl/index.html (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Gupta, Priya S. 2015. Governing the single-family house: A (brief) legal history. University of Hawai’i Law Review 37: 187–243. [Google Scholar]

- Hadler, Tara. 2014. How The Making of a Mega-City Prompted Partnerships for Sustainability. Network for Business Sustainability. May 12. Available online: https://www.nbs.net/articles/how-the-making-of-a-mega-city-prompted-partnerships-for-sustainability (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Harper, Lina. 2009. Group aims to save legacy of Montréal’s red light district: City threatens demolition of historic bar. Xtra. June 17. Available online: https://www.dailyxtra.com/group-aims-to-save-legacy-of-Montréals-Red Light-district-36404 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Hayes, Molly. 2018. The Last Dance: Why the Canadian Strip Club Is a Dying Institution. The Globe and Mail. September 4. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-the-last-dance-why-the-canadian-strip-club-is-a-dying-institution/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Herland, Karen. 2005. Organized Righteousness against Organized Viciousness: Constructing Prostitution in Post World War I Montreal. Master’s thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada. Available online: https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/000000531 (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Hubbard, Petra L. 2016. Planning for sex/work. In Queering Planning Challenging Heteronormative Assumptions and Reframing Planning Practice. Edited by Petra L. Doan. London: Routledge, pp. 169–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, Phil, Spike Boydell, Penny Crofts, Jason Prior, and Glen Searle. 2013. Noxious neighbours? Interrogating the impacts of sex premises in residential areas. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 45: 126–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, David. 2013. The critical policy discourse analysis frame: Helping doctoral students engage with the educational policy analysis. Teaching in Higher Education 18: 833–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. 2020. Mapping Responses by Cooperatives and Social and Solidarity Economy Organizations to Forced Displacement. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---ddg_p/documents/publication/wcms_742930.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2022).

- Jacques, Paola Berenstein. 2011. Urban improvisations: The profanatory tactics of spectacularized spaces. Brazilian Improvisations 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Ronald John, Peter J. Taylor, and Michael J. Watts. 2002. Geographies of Global Change: Remapping the World, 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Juan-Luis, and Richard G. Shearmur. 2017. Montréal: La Cité des Cités. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, Alex. 2009. Where and how does urban design happen? In Urban Design. Edited by Alex Krieger and William S. Saunders. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, Elsa. 2007. Sidewalk spectacular. Canadian Architect 52: LS6–LS8. [Google Scholar]

- Lavorato, Mark. 2014. Roaring Montréal. National Post. April 28. Available online: https://nationalpost.com/opinion/mark-lavorato-roaring-Montréal (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Lee, Samuel, and Petra Persson. 2021. Human Trafficking and Regulating Prostitution. IFN Working Paper No. 996, NYU Stern School of Business EC-12-07, NYU Law and Economics Research Paper No. 12-08. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2057299 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2057299. (accessed on 10 September 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Loopmans, Maarten, and Pieter van Den Broeck. 2011. Global pressures, local measures: The re-regulation of sex work in the Antwerp Schiperskwartier. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 102: 548–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Tara, Andrea Krüsi, Leslie Pierre, Will Small, and Kate Shannon. 2017. The impact of construction and gentrification on an outdoor trans sex work environment: Violence, displacement and policing. Sexualities 20: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, Adrienne A. 2012. The Conditions of Area Restrictions in Canadian Cities: Street Sex Work and Access to Public Space. Master’s thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maginn, Paul J., and Christine Steinmetz. 2014. Conclusion: Towards pragmatic regulation of the sex industry. In (Sub)Urban Sexscapes. London: Routledge, pp. 261–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mendel, Jonathan, and Kiril Sharapov. 2016. Human trafficking and online networks: Policy, analysis, and ignorance. Antipode 48: 665–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud O’Grady, Liam. 2015. “La Répression, ça Finit par Donner des Résultats”: The Displacement and Erasure of Street Culture in Downtown Montréal 1995–2010. Master’s thesis, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada. Available online: https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/980475/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Mortimer, Sarah. 2009. Shedding a red light on history. The McGill Daily. November 9. Available online: https://www.mcgilldaily.com/2009/11/shedding_a_red_light_on_history/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Namaste, Ki. 1996. Genderbashing: Sexuality, gender, and the regulation of public space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 14: 221–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namaste, Viviane. 2000. Invisible Lives: The Erasure of Transsexual and Transgendered People. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Namaste, Viviane. 2014. Quartier des spectacles: What’s Invisible Is Spectacular. Dare-Dare. Available online: https://www.dare-dare.org/en/events/viviane-namaste (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Neuwelt-Kearns, Caitlin, Tom Baker, and Octavia Calder-Dawe. 2020. Informal governance and the spatial management of street-based sex work in Aotearoa New Zealand. Political Geography 79: 102154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normandin, Pierre-André. 2018. Quartier des Spectacles: Des caméras pour évaluer les foules. La Presse. October 15. Available online: https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/grand-Montréal/201810/14/01-5200224-quartier-des-spectacles-des-cameras-pour-evaluer-les-foules.php (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Nussbaum, Martha C. 2010. From Disgust to Humanity: Sexual Orientation and Constitutional Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Office de consultation publique de Montréal. 2009. Quadrilatère Saint-Laurent, Rapport de Consultation Publique. Available online: https://ocpm.qc.ca/fr/consultation-publique/quadrilatere-saint-laurent (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Office de consultation publique de Montréal. 2013. PPU du Quartier des Spectacles—Pôle du Quartier Latin. Available online: https://ocpm.qc.ca/fr/consultation-publique/ppu-quartier-spectacles-pole-quartier-latin (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Oselin, Sharon S., Katie Hail-Jares, and Melanie Kushida. 2022. Different strolls, different worlds? Gentrification and its impact on outdoor sex work. Social Problems 69: 282–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriquin, Martin. 2011. Nobody puts Cleopatra in the corner. Maclean’s. June 16. Available online: https://www.macleans.ca/economy/business/nobody-puts-cleopatra-in-the-corner/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Quartier des Spectacles Partnership. 2020. History and Vision of the Quartier des Spectacles. Available online: https://www.quartierdesspectacles.com/en/about/history-and-vision/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Quartier des Spectacles Partnership. 2022. Montreal’s Downtown Strategy: Focusing on Culture, Collaboration and Innovation. Available online: https://www.quartierdesspectacles.com/en/media/montreals_downtown# (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Ross, Becki L. 2010. Sex and (evacuation from) the city: The moral and legal regulation of sex workers in Vancouver’s West End, 1975–1985. Sexualities 13: 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, David. 2009. The use of partnering as a conflict prevention method in large-scale urban projects in Canada. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2: 401–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Laurent Montréal. 2020. Regulations: Acquired Rights; City of Montréal. Available online: https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/ARROND_SLA_EN/MEDIA/DOCUMENTS/FICHES/REGULATIONS_ACQUIRED_RIGHTS.PDF (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Shoukri, Maya. 2011. Café Cleopatra refuses to relocate: Owner resists “revitalization” of the Quartier des Spectacles. The McGill Daily. March 19. Available online: https://www.mcgilldaily.com/2011/03/cafe-cleopatra-refuses-to-relocate/ (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Sitte, Camillo. 1889. City Planning According to Artistic Principles. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Spanger, Marlene. 2011. Human trafficking as a lever for feminist voices? Transformations of the Danish policy field of prostitution. Critical Social Policy 31: 517–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Samuel. 2019. Planning gentrification. In Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State. London: Verso, pp. 49–92. [Google Scholar]

- Stella l’amie de Maimie. 2008. Mémoire; City of Montréal. Available online: https://ville.montreal.qc.ca/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/COMMISSIONS_PERM_V2_FR/MEDIA/DOCUMENTS/MEMOIRE-SP_STELLA_20080415.PDF (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Stella l’amie de Maimie. 2012. ConSTELLAtion: Human Rights Issue; Dépôt légal, Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec. Available online: https://chezstella.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Constellation-Droits-Humains.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Sylvestre, Marie-Eve, William Damon, Nicholas Blomley, and Céline Bellot. 2015. Spatial tactics in criminal courts and the politics of legal technicalities. Antipode 47: 1346–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanik, Geneviève, Chantal Ismé, and Élaine Grisé. 2014. Portrait de l’industrie du Sexe au Québec: Rapport Sommaire. Concertation Des Luttes Contre L’exploitation Sexuelle. Available online: https://www.lacles.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/Sommaire-portrait-final-CLES-2.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2022).