Towards a Conceptual Understanding of an Effective Rural-Based Entrepreneurial University in South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Historical Roles of Universities

3. The Entrepreneurial University

4. Introduction of Entrepreneurial Universities in South Africa

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Study Area

5.2. Methodology

6. Results and Discussion of Findings

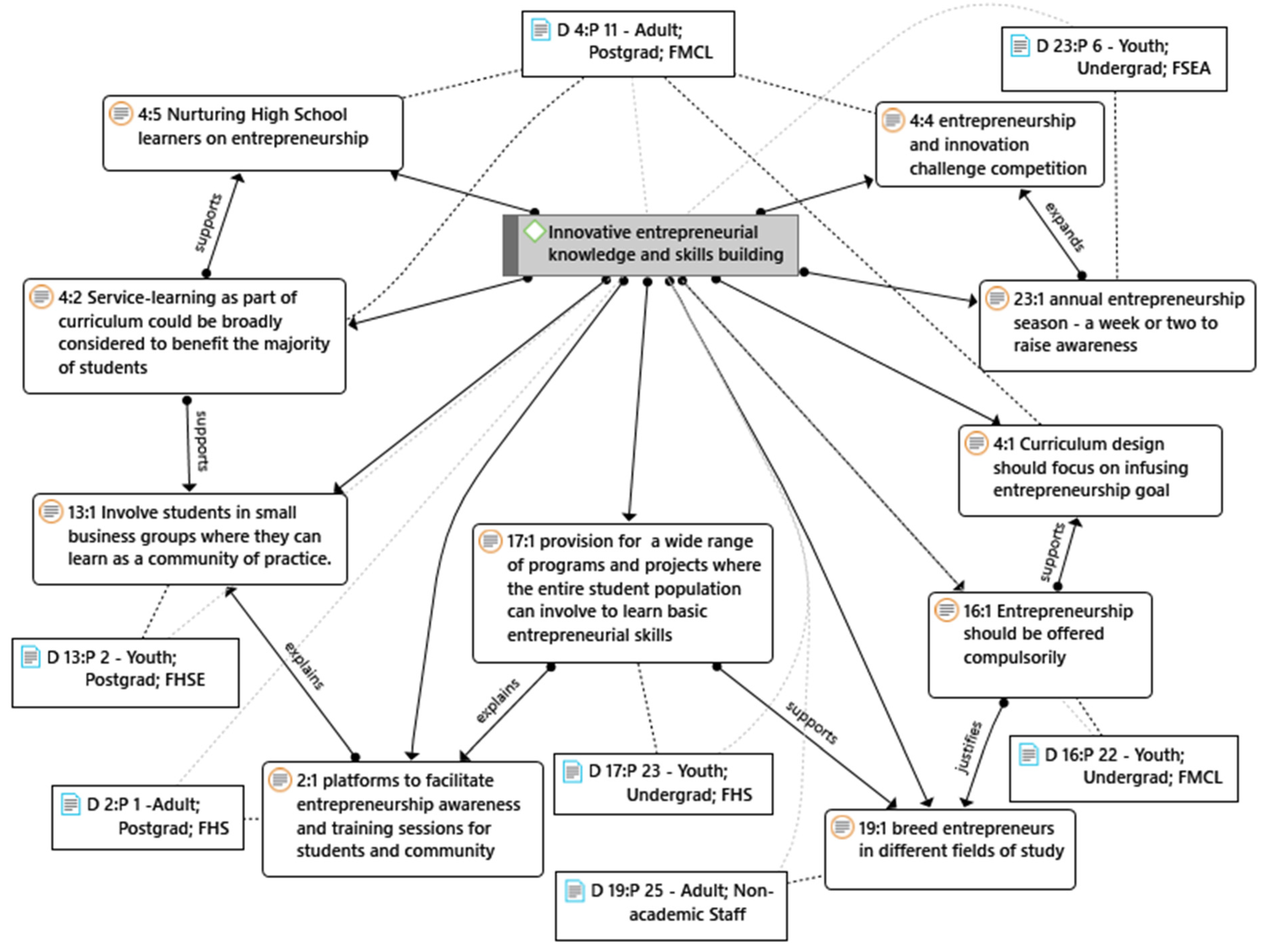

6.1. Entrepreneurial Knowledge and Skill Building

“… it should be a university that teaches students the different tools to do business across disciplines, identify unique patterns of applying entrepreneurship in each field of study and/or how to make entrepreneurial value from distinct specializations and degrees”.(P 25—Adult; Non-academic Staff)

“We envisage an entrepreneurial university that has a cohort of academic-entrepreneurs who have high business knowledge, are innovative in teaching and learning and research to groom students who can turn around their learning and research into a business idea that brings solutions for societal gain”.(P 24—Adult; Community member)

“… have a system that can provide a flexible and dynamic environment such that the orientation for enterprise venturing is not limited to disciplines or Schools …”.(P 7—Youth; Postgrad; FMCL)

“At present, entrepreneurship is offered as a module in some Departments within the School of Agriculture and School of Management Sciences. Knowledge plays a pivotal role in students’ development in the course. This ‘offering’ should be made accessible to all Departments across Schools. … in fact, entrepreneurship knowledge should be offered as a compulsory base module in the University just like the general modules …”.(P 22—Youth; Undergrad; FMCL)

“… put in place strategies of knowledge-building which will enable the educating of primary school pupils and the nurturing of high school learners, specifically, on basic entrepreneurship. This can lay the proper foundation such that the youth transition into higher institutions not only being well-embedded academically but also with entrepreneurial intentions and/or already engaged in its practices”.(P 11—Adult; Postgrad; FMCL)

“… it is essential to have a wide range of programs and projects where majority of the student can involve to learn basic entrepreneurial skills, sometimes, attach them to mentor …”.(P 23—Youth; Undergrad; FHS)

“… entrepreneurship taught is important but that alone cannot suffice and/or guarantee entrepreneurial mindset and intention. … the process should be facilitated in dimensions, complementing practical skills, mentorship, internship programs, and venturing seed funds opportunities …”(P 7—Youth; Postgrad; FMCL)

“… intensify service-learning …” “it creates platforms where the university actors and community members co-interrogate and co-design solutions to challenges societies face. In between, the University and grassroots communities where service is rendered are the students who work and benefit from the progressive learning experience …”.(P 11—Adult; Postgrad; FMCL)

“… you know the local farmers and business owners in the villages have essential entrepreneurial experience the University can tap from. It can strengthen its ties with them, such that students are placed there as an apprentice to acquire knowledge and skills …, this is experimental entrepreneurship one cannot find anywhere in the classroom …”.(P 32—Adult; Municipal official)

“… the university entrepreneurship framework should provide for annual entrepreneurship season—it can be for a week or two to sensitize the masses. In this, there can be series of events ranging from product showcasing, soft skills training, presentations and motivational talks based on lived experiences, competitions and celebration of student entrepreneurship”.(P 6—Youth; Undergrad; FSEA)

“… it is important to see the University hosting specific entrepreneurship and innovation challenge competition for staff and students in respective faculties and departments”.(P 11—Adult; Postgrad; FMCL)

“… create more platforms to facilitate entrepreneurship awareness, sensitization and training sessions for students and community members. This has a role to play in creating an effective entrepreneurial atmosphere, awakening, as well as strengthening entrepreneurial culture and spirit”.(P 1—Adult; Postgrad; FHS)

“… during training or programs, engaging students in small business groups where they can learn as a community of practice is paramount and can enhance mutual skills development”.(P 2—Youth; Postgrad; FHSE)

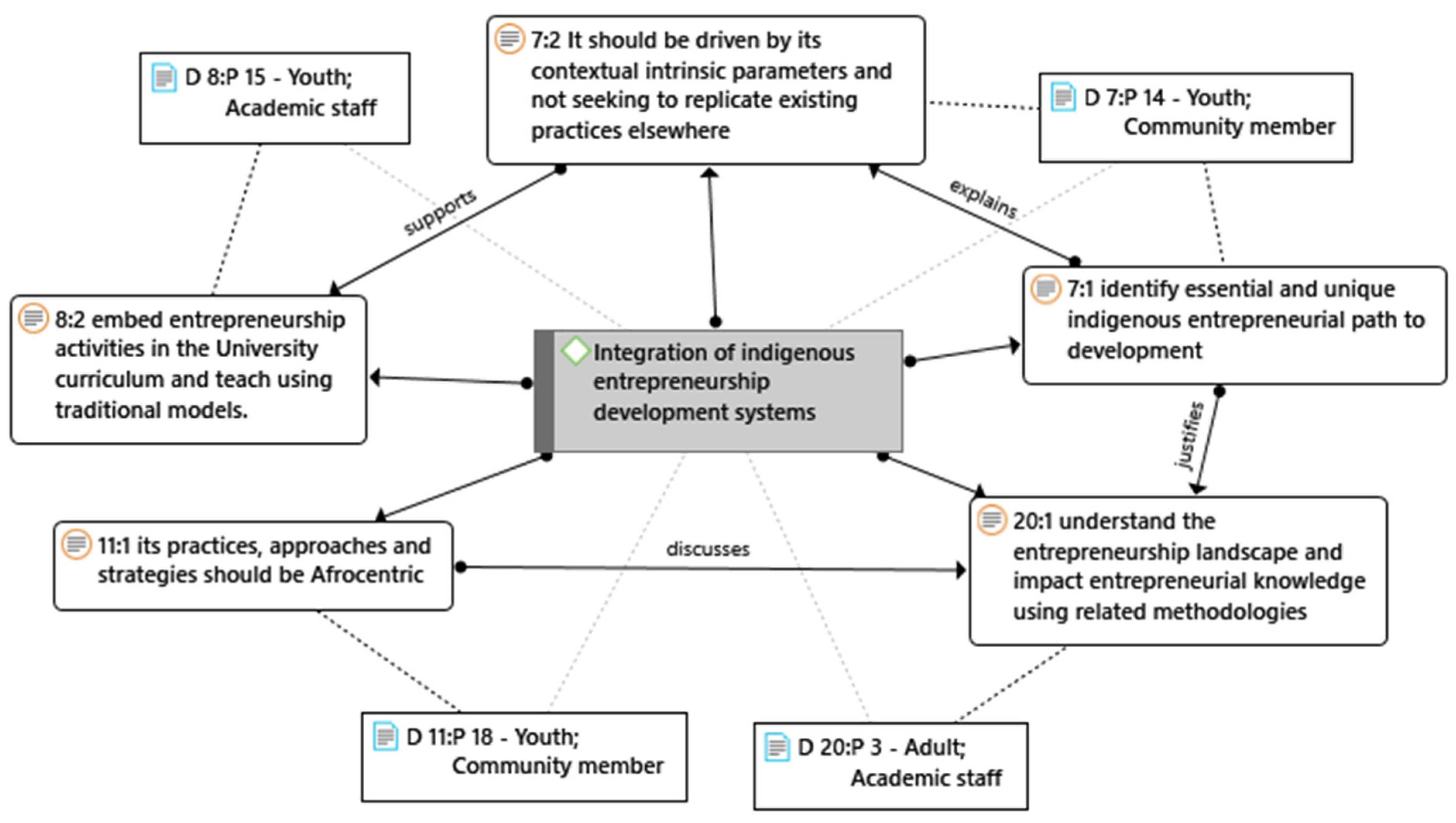

6.2. Integration of Indigenous Entrepreneurship Systems

“… it should be a university that can successfully identify an essential and unique entrepreneurial path to development. Entrepreneurship knowledge-building, teaching, research and community engagement should be informed by indigenous models that are compatible with the realities of South Africa’s landscape. It must be driven by its contextual intrinsic parameters and not seek to replicate practices existing elsewhere which may not speak to our peculiar issues. Only when this is sorted and implemented, can the University be entrepreneurial enough to understand and relate well with emerging and peculiar issues in this area, thereby, direct targeted support to society …”.(P 14—Youth; Community member)

“… very often, universities, colleges and entrepreneurship development agencies use foreign models to facilitate entrepreneurship capacity-building in local areas that require a more traditional approach to enterprise venturing. The lack of knowledge mix and linkage is one of the reasons most young entrepreneurs, especially those that have been trained and funded by some entrepreneurship agencies or institutions fail”.(P 32—Adult; Municipal official)

“… emphatically, a more pragmatic approach to entrepreneurship-knowledge transfer is needed not only in this University but institutions of higher learning across the country because very often what students are being taught in the classroom is far from actual realities in the entrepreneurial field. Our higher institutions are regurgitating and diffusing knowledge to survive and not imparting the form of education required to thrive in our local entrepreneurial landscape …”.(P 15—Youth; Academic staff)

“Do teachers at the University have the essential skills to impart core entrepreneurial knowledge relating to what we do every day? Are students being taught about traditional African business patterns? Is the syllabus still being complemented with numerous western theories and methodologies such as … that do not even apply to our systems? Are community members and local entrepreneurs who have practical experience involved in the planning and designing process of the entrepreneurial university? These are probably some of the questions you should answer because they determine the nature of the entrepreneurial university needed here in Vhembe District and South Africa at large”.(P 18—Youth; Community member)

“… an average student will learn a subject, pass and forget it if the content is presented in a manner where they can envisage it is not relevant to the society in which they find themselves. It is important to use realistic approaches to communicate entrepreneurship to students; they should see it fits and applies to their ecosystem”.(P 3—Adult; Academic staff)

“… I anticipate the teachers to become entrepreneurial such that they understand the specific methods and approaches that can be harnessed to impart entrepreneurial knowledge to students. They should be able to convert the knowledge they gained in class to a business concept or model …”.(P 20—Youth; Postgrad; FSEA)

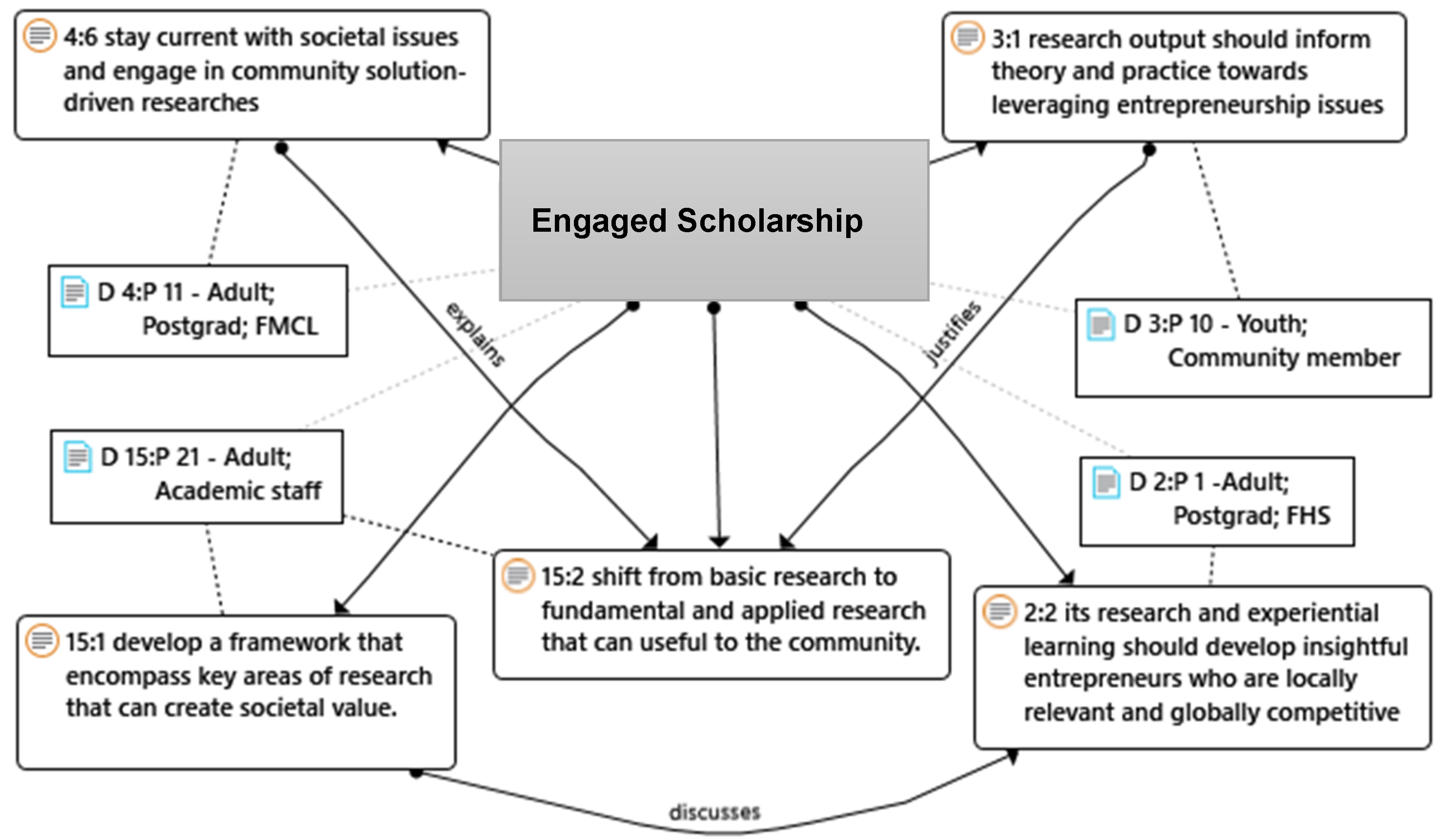

6.3. Engaged Scholarship

“… enterprise failure in South Africa is alarming, contributing to job losses, increasing rate of unemployment, poverty and even crime. What is the problem? Where is it coming from? How can it be solved? Our universities should serve as knowledge producers and perform relevant research projects not only to provide answers to these questions but they must also identify more proactive and dynamic ways of engaging with policymakers, entrepreneurship agencies and grassroots entrepreneurs for a sustained solution…”(P 32—Adult Municipal official)

“… a university that researches to provide knowledge and goes back to societies with the outcome, specifically, on how to manage a successful business, becomes resilient, competitive and sustainable.” This is lacking in many traditional universities; Univen, as a rural-based institution of higher learning located in an area where these problems are outrageous should be concerned about solving them …”.(P 10—Youth; Community member)

“The University can shift from basic research to fundamental and applied research that is useful to the community … and should work closely with community members to understand the nature of problems they face to determine the dimension of research undertakings”.(P 21—Adult; Academic staff)

“… it should use its research and experiential learning to develop insightful student and local entrepreneurs who are locally relevant and globally competitive in developing innovative solutions to complex societal problems”.(P 1—Adult; Postgrad; FHS)

“… It is time the university develops a framework that encompasses key areas of research that can create societal value. There should be an active strategy for funding to attract researchers’ interest in the niche and plans to commercialise the end products. Postgraduates and academics should focus their research initiatives on community issues and it has to be solution-driven”.(P 21—Adult; Academic staff)

“… being practical comes with massive impact. Firstly, it will enable the generation of diverse ideas and solutions towards solving community problems and secondly, it enhances the production of marketable graduates given that they are directly involved in the knowledge-building process and technology transfer for societal impact”.(P 11—Adult; Postgrad; FMCL)

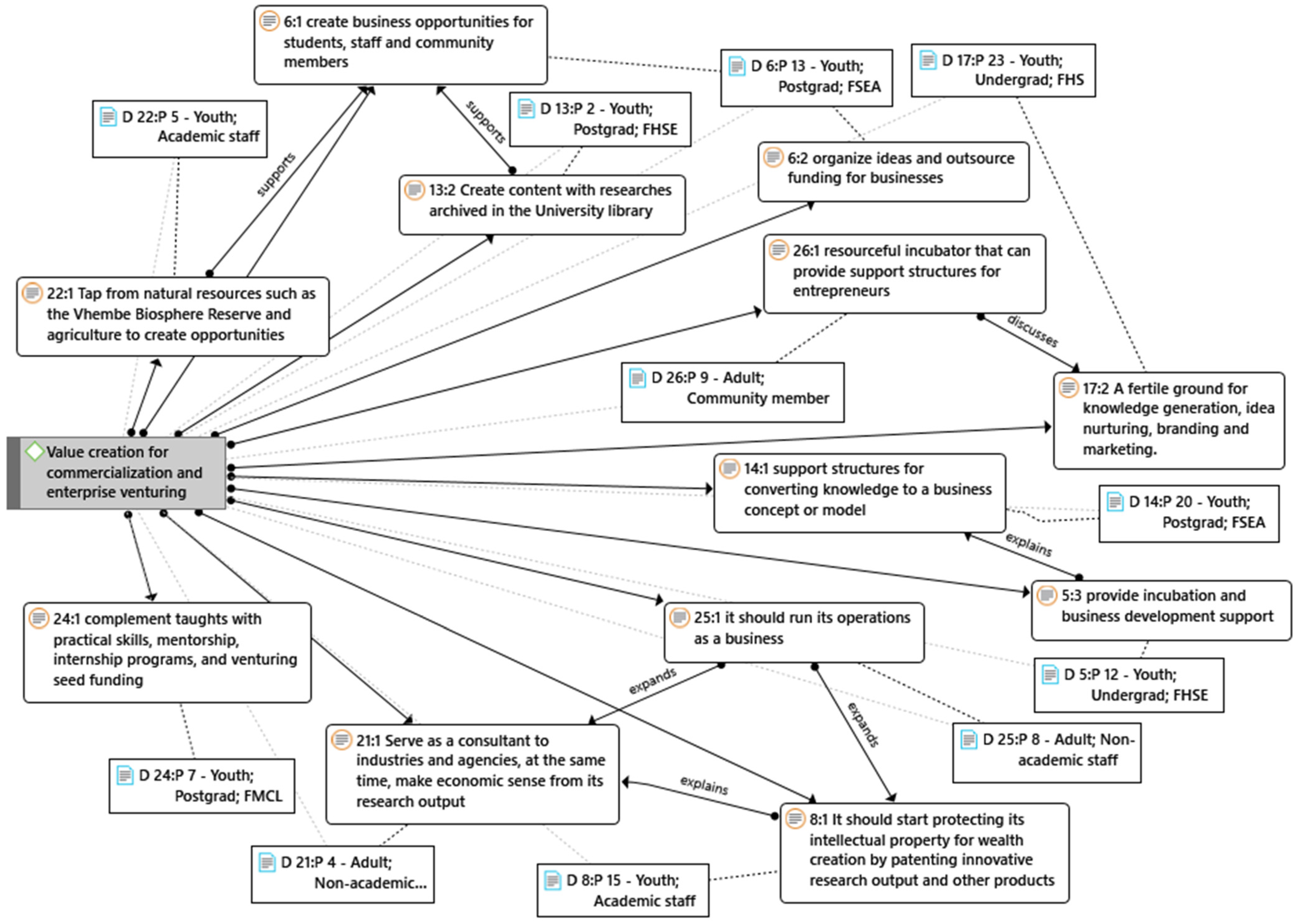

6.4. Value Creation for Commercialisation and Venturing

“… Vhembe District is the capital of natural wealth in Limpopo province with untapped resources, such as the Vhembe Biosphere, Phiphidi Waterfall, Nandoni Dam and several other surrounding sites which have potential for industrial eco-tourism. It is also known for indigenous products in medicine and local craft. These resources are underutilised at the moment even though they have strong business potential. There is a need for the university to interact with grassroots communities, government, entrepreneurship agencies as well as entrepreneurs on the ground to harness them broadly and pave way for more businesses with a greater impact on economic development. The curriculum should be that which provides students with practical and innovative skills to venture in all these opportunities that are readily available and not graduating with mere traditional degrees that are not in demand …”.(P 5—Youth; Academic staff)

“… the University is strategically situated where it can access vast and fertile land. The Faculty of Agriculture, Environmental Sciences and Management Science must know how to make essential use of it for business impact. Firstly, the expansion of some of the farms, for example commercialising eggs, chickens and cattle will have a great impact on revenue and local employment. Secondly, cassava grows perfectly well on the soil and has great potential for sugar production which is one of the largest selling products in Southern Africa. How about building a factory?”.(P 13—Youth; Postgrad; FSEA)

“… step up research awareness to motivate institutional culture as well as interests and intention; these are lacking in the University. Capacity development in terms of research training, staff and postgraduate research funding initiatives should be revisited and enhanced accordingly. At present, I feel that knowledge and research commercialisation is unattainable because we cannot sell what we do not have! Both the quality and quantity commercial are lacking; with the ongoing institutional reforms and political undertone which compromises merit and productivity as well as exploit and discriminate against some scholars, especially black migrants whose contribution to the University’s research enterprise are unprecedented, I doubt that the transformation in question is viable. I am not in any doubting the capabilities of the locals, it is already gearing that putting harsh conditions on the ground to tactically remove resource foreign scholars in the system has resulted to low productivity. This is a serious concern to visit if one is talking about transformation …”.(P 15—Youth; Academic staff)

“… with so much already being researched and archived in the university library, we expect valuable products out of it. The University should be generating income directly from its research to augment the government subsidy that is being received annually. This is necessary for its self-sustenance …”.(P 2—Youth; Postgrad; FHSE)

“… it should be a university that runs its operations as a business. For instance, when it comes to research and innovation, an entrepreneurial university strives towards the practice of marketable research outputs, publication contents and other forms of innovative products”.(P 8—Adult; Non-academic staff)

“… ‘no two ways’ about that; it’s simply redirecting focus to research areas in high demand within the local and/or regional economy and ensures that each innovation is patent such that it becomes a property for the university—this is an income stream”.(P 15—Youth; Academic staff)

“… as far as I know, entrepreneurial universities are fertile ground for knowledge generation, idea nurturing, branding and marketing. Having the right people and relevant technology in place can stimulate transformation, build entrepreneurial capacity and enable students and staff members to commercialise their innovation”.(P 23—Youth; Undergrad; FHS)

“… the typology and nature of entrepreneurial support the university offer to students, as well as staff and community members counts. There should be initiatives on the ground that stimulates entrepreneurial venturing. I am aware of ENACTUS, the STEP programme and various entrepreneurial institutional projects running at the University. However, one is tempted to as the number of students and/or staff entrepreneurs the university has produced and supported through these structures to establish a sustainable business? If there are any, are their businesses thriving? There should be an impact assessment to determine the dimension of entrepreneurial support systems we need here. It is not all about the programmes but the resultant impact. I think it is time for the University to engage in entrepreneurial activities for their actual impact and not just for the sake of report. It should map out modalities to strategically support students who are innovative to put their ideas into play, and support them through all strategies to grow large enterprises in the country”.(P 12—Youth; Undergrad; FHSE)

“… it can as well set up a standard business incubation system in the region that has the needed support structures to initiate new ventures. This is essential for its internal revenue given as short courses can be offered and paid for…”.(P 9—Adult; Community member)

6.5. Embedding Resourceful Stakeholders in the Value-Chain Network

“… implementing ideas is one big challenge many University students confront when they come across an opportunity. Many students have great ideas but lack access to guidance and resources for their implementation … Strengthening ties with agencies such as NYDA can be of great help. Through, students can access various supports from the agencies”.(P 17—Youth; Agency representative)

“… we [SEDA] can co-create a better entrepreneurial environment for young entrepreneurs to thrive by strengthening our relations and scaling up context-specific investments in needed areas. … we work with other agencies to mentor and provide funding for innovative young entrepreneurs. It would be a great deal for the University to come up with a structure that can help identify entrepreneurial-minded individuals in its locality for this endeavour …”.(P 19—Adult; Agency representative)

“… collaborating with successful enterprises, especially big firms will pave way for placements of graduates in companies; this is essential for practical experience. It also enables networking with individuals in the real business environment who can be resourceful for start-ups …”.(P 8—Adult; Non-academic staff)

“… It should be a kind of University that teaches and at the same time learns from others, I mean, that which recognizes and is willing to work with and learn from successful entrepreneurs in its locality… these people already know how the ecosystem operates and what is needed to operate successfully in the system …”.(P 10—Youth; Community member)

“… there are traditional model entrepreneurs in Thohoyandou and South Africa at large are using that can be useful to the University. Even that of foreign entrepreneurs, especially the Indians, Pakistanis, Ethiopians, Somalians and Nigerians. These people are highly successful and have occupied South Africa’s market with their business patens. What is the secret behind their success? What are the concepts driving their businesses? And how can we learn from them? I think they understood the entrepreneurship landscape better, hence, become more resilient and competitive than most of our local entrepreneurs here. … we can work with them to distil knowledge points as this will enrich our entrepreneurial pedagogy. I think also that through an MoU, students and local entrepreneurs may be placed in some of these enterprises for internship and mentorship …”.(P 16—Youth; Academic Staff)

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abreu-Pederzini, Gerardo David, and Manuel F. Suárez-Barraza. 2020. Just let us be: Domination, the postcolonial condition, and the global field of business schools. Academy of Management Learning and Education 19: 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfalih, Abdulaziz Abdulmohsen, and Wided Mohamed Ragmoun. 2019. The role of entrepreneurial orientation in the development of an integrative process towards en-trepreneurship performance in entrepreneurial university: A case study of Qassim university. Management Science Letters 10: 1857–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, Philip G. 2008. The Complex Roles of Universities in the period of Globalization. In Higher Education in the World 3: New Challenges and Emerging Roles for Human and Social Development. Edited by Palgrave MacMillan. Barcelona: Universitat Politecnica De Catalunya. Available online: http//upcommons.upc.edu/revistes/handle/2099/8111 (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Amaechi, Kingsley E., Ishmael O. Iwara, Prince O. Njoku, Nanga R. Raselekoane, and Tsoaledi D. Thobejane. 2021. The Igbo Traditional Business School and Success of Igbo-Run Small and Medium Size Enterprises in Diaspora: Evidence from Limpopo Province, South Africa. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 27: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio, Sebastian, David Urbano, and David Audretsch. 2016. Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: Panel data evidence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 102: 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arko-Achemfuor, Akwasi. 2012. Financing Small, Medium and Micro-Enterprises (SMMEs) in Rural South Africa: An Exploratory Study of Stokvels in the Nailed Local Municipality, North West Province. Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology 3: 127–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asongu, Simplice A., and Nicholas M. Odhiambo. 2019. Challenges of doing business in Africa: A systematic review. Journal of African Business 20: 259–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, David B., Marcel Hülsbeck, and Erik E. Lehmann. 2012. Regional competitiveness, university spillovers, and entrepreneurial activity. Small Business Economics 39: 587–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baporikar, Neeta. 2019. Significance and Role of Entrepreneurial University in Emerging Economies. International Journal of Applied Management Sciences and Engineering (IJAMSE) 6: 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, David V. 2016. Twenty First Century Education: Transformative Education for Sustainability and Responsible Citizenship. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability 18: 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellotti, Francesco, Riccardo Berta, Alessandro De Gloria, Elisa Lavagnino, F. Dagnino, Michela Ott, Margarida Romero, Mireia Usart, and Igor S. Mayer. 2012. Designing a course for stimulating entrepreneurship in higher education through serious games. Procedia Computer Science 15: 174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikse, Veronika, Inese Lusena-Ezera, Baiba Rivza, and Tatjana Volkova. 2016. The Transformation of Traditional Universities into Entrepreneurial Universities to Ensure Sustainable Higher Education. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability 18: 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bøllingtoft, Anne. 2012. The bottom-up business incubator: Leverage to networking and cooperation practices in a self-generated, entrepreneurial-enabled environment. Technovation 32: 304–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, Geoffrey, and Colin Lucas. 2011. What are universities for? Chinese Science Bulletin 56: 2506–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantoni, Davide, and Noam Yuchtman. 2014. Medieval universities, legal institutions, and the commercial revolution. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129: 823–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, Piera, Roberto Cerchione, and Emilio Esposito. 2019. Exploration and exploitation in the development of more entrepreneurial universities: A twisting learning path model of ambidexterity. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 141: 172–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceresia, Francesco, and Claudio Mendola. 2019. Entrepreneurial Self-Identity, Perceived Corruption, Exogenous and Endogenous Obstacles as Antecedents of Entrepreneurial Intention in Italy. Social Sciences 8: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerver Romero, Elvira, João J. M. Ferreira, and Cristina I. Fernandes. 2021. The multiple faces of the entrepreneurial university: A review of the prevailing theoretical approaches. The Journal of Technology Transfer 46: 1173–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, Chimene. 2021. Study on Advancing Entrepreneurial Universities in Africa. United Nations Economic Commission for Africa Report. Pretoria: United Nations Economic Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Burton. R. 1998. The entrepreneurial university: Demand and response. Tertiary Education and Management 4: 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W, and J. David Creswell. 2017. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Darley, William K., and Denise J. Luethge. 2019. Management and business education in Africa: A post-colonial perspective of international accreditation. Academy of Management Learning and Education 18: 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, Pascal Samfoga, Jussi S. Jauhiainen, and Rosemond Boohene. 2021. The synergistic role of academic entrepreneurship patterns in entrepreneurial university transformation: Analysis across three African sub-regions. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Sánchez, Amador, María de la Cruz Del Río, José Álvarez-García, and Diego Fernando García-Vélez. 2019. Mapping of scientific coverage on education for Entrepreneurship in Higher Education. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 13: 84–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzomonda, Obey, and Olawale Fatoki. 2019. The role of institutions of higher learning towards youth entrepreneurship development in South Africa. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal 25: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbers, Joris J. 2014. Networking behavior and contracting relationships among entrepreneurs in business incubators. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elert, Niklas, Fredrik W. Andersson, and Karl Wennberg. 2015. The impact of entrepreneurship education in high school on long-term entrepreneurial performance. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 111: 209–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khasawneh, Bashar S. 2008. Entrepreneurship promotion at educational institutions: A model suitable for emerging economies. WSEAS Transactions on Business and Economics 2: 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Estrin, Saul, Julia Korosteleva, and Tomasz Mickiewicz. 2013. Which institutions encourage entrepreneurial growth aspirations? Journal of Business Venturing 28: 564–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, Henry. 2013. Anatomy of the entrepreneurial university. Social Science Information 52: 486–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, Henry. 2016. The entrepreneurial university: Vision and metrics. Industry and Higher Education 30: 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, Henry, and Loet Leydesdorff. 1997. Introduction to special issue on science policy dimensions of the Triple Helix of university-industry-government relations. Science and Public Policy 24: 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, Henry, and Chunyan Zhou. 2017. The Triple Helix: University–Industry–Government Innovation and Entrepreneurship. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, James Dzisah, and Michael Clouser. 2021. Shaping the entrepreneurial university: Two experiments and a proposal for innovation in higher education. Industry and Higher Education 36: 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Alles, Mariluz, Juan Pablo Diánez-González, Tamara Rodríguez-González, and Mercedes Villanueva-Flores. 2018. TTO characteristics and university entrepreneurship: A cluster analysis. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management 10: 861–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, Somariah, Sintha Wahjusaputri, and Ahmad Diponegoro. 2019. Success Factors in Triple Helix Coordination: Small-Medium Sized Enterprises in Western Java. Etikonomi 18: 233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, Lene, and David V. Gibson, eds. 2015. The Entrepreneurial University: Context and Institutional Change. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, Joseph, Beata Kilonzo, and Pertina Nyamukondiwa. 2016. Student-perceived criteria for assessing university relevance in community development. South African Journal of Science 112: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusch, Patricia I., and Lawrence R. Ness. 2015. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report 20: 1408–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, Will, and Dimitrios Pontikakis. 2008. From ivory tower to factory floor? How universities are changing to meet the needs of industry. Science and Public Policy 35: 462–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, Maribel, and David Urbano. 2012. The development of an entrepreneurial university. The Journal of Technological Transfer 37: 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassi, Abderrahman. 2016. Effectiveness of early entrepreneurship education at the primary school level: Evidence from a field research in Morocco. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education 15: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattab, Hala W. 2014. Impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Egypt. The Journal of Entrepreneurship 23: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Laura Rosendahl, Randolph Sloof, and Mirjam Van Praag. 2014. The effect of early entrepreneurship education: Evidence from a field experiment. European Economic Review 72: 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzelt, Annamaria. 2004. The evolution of university–industry–government relationships during transition. Resources Policy 33: 975–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwara, Ishmael Obaeko. 2020. Towards a Model for Successful Enterprises Centred on Entrepreneurs Exogenous and Endogenous Attributes: Case of Vhembe District, South Africa. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Iwara, Ishmael Obaeko, Vhonani Olive Netshandama, Beata Kilonzo, and Jethro Zuwarimwe. 2019. Sociocultural issues contributing to poor youth involvement in entrepreneurial activities in South Africa: A prospect of young graduates in Thohoyandou. AFFRIKA Journal of Politics, Economics and Society 9: 111–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J. 2019. Jonathan Jansen to Nigerians: ‘I Apologise for the Reckless Generalisations’. Timeslive. September 12. Available online: https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2019-09-12-jonathan-jansen-to-nigerians-i-apologise-for-the-reckless-generalisations/ (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Jansen van Nieuwenhuizen, P. J. 2012. The entrepreneurial university. Management Today 30: 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, Vegard, and Tommy Høyvarde Clausen. 2011. Promoting the entrepreneurs of tomorrow: Entrepreneurship education and start-up intentions among schoolchildren. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 13: 208–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, Simy, and Latha Poonamallee. 2013. Cross-cultural teaching in globalized management classrooms: Time to move from functionalist to postcolonial approaches? Academy of Management Learning and Education 12: 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasi, Yvonne. 2018. Challenges Faced by Rural-Women Entrepreneurs in Vhembe District: The Moderation ROLE of gender Socialization. Master’s dissertation, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Kariuki, Paul, and Lizzy Oluwatoyin Ofusori. 2017. WhatsApp-Operated Stokvels Promoting Youth Entrepreneurship in Durban, South Africa: Experiences of Young Entrepreneurs. Paper presented at the 10th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, New Delhi, India, May 7–9; pp. 253–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kativhu, Simbarashe. 2019. Criteria for Measuring Resilience of Youth-Owned Small Retail Businesses in Selected Rural Areas of Vhembe District, South Africa. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby, David A. 2005. Creating entrepreneurial universities in the UK: Applying entrepreneurship theory to practice. Journal of Technology Transfer 31: 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, D. A., Maribel Guerrero, and David Urbano. 2011. The theoretical and empirical side of entrepreneurial universities: An institutional approach. Canadia Journal of Administrative Sciences 28: 302–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkley, William W. 2017. Cultivating entrepreneurial behaviour: Entrepreneurship education in secondary schools. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 11: 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Simone Boruck, Maria Celeste Reis Lobo de Vasconcelos, Reginaldo de Jesus Carvalho Lima, and Simone Cristina Dufloth. 2021. Contributions from entrepreneurial universities to the regional innovation ecosystem of Boston. Revista Gestão and Tecnologia 21: 245–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kripa, Dorina, Edlira Luci, Klodiana Gorica, and Ermelinda Kordha. 2021. New Business Education Model for Entrepreneurial HEIs: University of Tirana Social Innovation and Internationalization. Administrative Sciences 11: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnen, F. 1978. The role of Agricultural Colleges in modern Society: The University as an instrument in social and economic development. Zeitschrift fur Ausladische Landwirtschaft, Jahrgang 17: 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowska, Anna, Mateusz Stopa, and Elżbieta Inglot-Brzęk. 2021. Innovativeness and entrepreneurship: Socioeconomic remarks on regional development in peripheral regions. Economics and Sociology 14: 222–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockyer, Joan. 2015. Educational Transformation and the Role of the Entrepreneurial University in Africa. Maas, G and (Jones, P. 2015) Systemic Entrepreneurship: Contemporary Issues and Case Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lose, Thobekani, and Lloyd Kapondoro. 2020. Functional elements for an entrepreneurial university in the South African context. Journal of Critical Reviews 7: 8083–88. [Google Scholar]

- Miszczak, S. M., and Z. Patel. 2018. The role of engaged scholarship and co-production to address urban challenges: A case study of the Cape Town Knowledge Transfer Programme. South African Geographical Journal= Suid-Afrikaanse Geografiese Tydskrif 100: 233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mncayi, Precious, and Steven Henry Dunga. 2016. Career choice and unemployment length: A study of graduates from a South African university. Industry and Higher Education 30: 413–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, Valentina, Gioconda Mele, and Pasquale Del Vecchio. 2019. Entrepreneurship education in tourism: An investigation among European Universities. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education 25: 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netshandama, Vhonani Olive, Ishmael Obaeko Iwara, and Ndamulelo Innocent Nelwamondo. 2021. Social Entrepreneurship Knowledge Promotion Amongst Students in a Historically Disadvantaged Institution of Higher Learning. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education 24: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nkamnebe, Anayo. 2008. Towards market-oriented entrepreneurial university management for Nigerian universities. International Journal of Management 7: 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nkondo, Livhuwani Gladys. 2017. Comparative Analysis of the Performance of Asian and Black-Owned Small Supermarkets in Rural Areas of Thulamela Municipality, South Africa. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Nkusi, Alain C., James A. Cunningham, Richard Nyuur, and Steven Pattinson. 2020. The role of the entrepreneurial university in building an entrepreneurial ecosystem in a post conflict economy: An exploratory study of Rwanda. Thunderbird International Business Review 62: 549–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloruntoba, Samuel Ojo. 2022. From Paradise Gain to Paradise Loss: Xenophobia and Contradictions of Transformation in South African Universities. In Conflict and Concord. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 109–28. [Google Scholar]

- Osorno-Hinojosa, Roberto, Mikko Koria, and Delia del Carmen Ramírez-Vázquez. 2022. Open Innovation with Value Co-Creation from University–Industry Collaboration. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, Swapan Kumar. 2019. Science and Technological Capability Building in Global South: Comparative Study of India and South Africa. In Innovation, Regional Integration, and Development in Africa: Rethinking Theories, Institutions, and Policies. Edited by Oloruntoba, Samuel Ojo and Mammo Muchie. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Petruzzelli, Antonio Messeni. 2011. The impact of technological relatedness, prior ties, and geographical distance on university-industry collaborations: A joint-patent analysis. Technovation 31: 309–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, Rómulo, and Bjørn Stensaker. 2014. Designing the entrepreneurial university: The interpretation of a global idea. Public Organization Review 14: 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, Vanessa, and Petrus Usmanij. 2021. Entrepreneurship education: Time for a change in research direction? The International Journal of Management Education 19: 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, Chanphirun, and Peter Van der Sijde. 2014. Understanding the concept of the entrepreneurial university from the perspective of higher education models. Higher Education 68: 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyerr, Akilagpa. 2004. Challenges facing African Universities: Selected issues. African Studies Review 47: 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattock, Michael. 2009. Entrepreneurialism in Universities and the Knowledge Economy: Diversification and Organizational Change in European Higher Education: Diversification and Organisational Change in European Higher Education. London: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, Brigitte. 2002. Atlas.ti for qualitative data analysis. Perspectives in Education 20: 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Taucean, Ilie Mihai, Ana Gabriela Strauti, and Monica Tion. 2018. Roadmap to entrepreneurial university—Case study. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 238: 582–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tella, Oluwaseun. 2018. South African higher education: The paradox of soft power and xenophobia. In The Political Economy of Xenophobia in Africa. Cham: Springer, pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- van Schalkwyk, François, and Tracy Bailey. 2013. Beyond Engagement: Exploring Tensions between the Academic Core and Engagement Activities at Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, South Africa (November 22, 2011). Beyond the Apartheid University? Critical Voices on Transformation in the University Sector. Edited by G. De Wet. Alice: University of Fort Hare Press, pp. 153–74. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, Christine, Kiri Dell, and Brigid Carroll. 2022. Decolonizing the Business School: Reconstructing the Entrepreneurship Classroom through Indigenizing Pedagogy and Learning. Academy of Management Learning and Education 21: 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Gaofeng. 2018. Impact of internship quality on entrepreneurial intentions among graduating engineering students of research universities in China. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 14: 1071–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuber-Skerritt, Ortrun, Lesley Wood, and Ina Louw. 2015. A Participatory Paradigm for an Engaged Scholarship in Higher Education: Action Leadership from a South African Perspective. Brill: Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

| Designation | Age Category | Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Youth | Adult | Male | Female | Sum | |

| Undergraduate students | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Postgraduate students | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Academic staff | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Non-academic staff | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Community members | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Municipal officials | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Entrepreneurship agency representatives | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| 19 | 14 | 15 | 18 | 33 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iwara, I.O.; Kilonzo, B.M. Towards a Conceptual Understanding of an Effective Rural-Based Entrepreneurial University in South Africa. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090388

Iwara IO, Kilonzo BM. Towards a Conceptual Understanding of an Effective Rural-Based Entrepreneurial University in South Africa. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(9):388. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090388

Chicago/Turabian StyleIwara, Ishmael Obaeko, and Beata Mukina Kilonzo. 2022. "Towards a Conceptual Understanding of an Effective Rural-Based Entrepreneurial University in South Africa" Social Sciences 11, no. 9: 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090388

APA StyleIwara, I. O., & Kilonzo, B. M. (2022). Towards a Conceptual Understanding of an Effective Rural-Based Entrepreneurial University in South Africa. Social Sciences, 11(9), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11090388