Abstract

The paper aims to investigate users’ behavior regarding inbound marketing while consuming content, in particular, to reveal the source of the reasons and triggers affecting content need in the case of long-consumption products. In the theoretical part of the article, the literature analysis is conducted in order to build a theoretical background. The variety of theories of content values as well as users’ decision-making processes are analyzed, and a conceptual view of the origins of content need is formed, which states that the need for a specific type of content emerges under the conditions of the consumer’s experienced gap of information or knowledge when in the stages of the buying model. In order to test this hypothesis, empirical research—the survey—was conducted. The main conclusion is that the decision-to-buy model makes a significant impact on the gap experienced by the consumer of the content and has the potential to be used to reveal the need for different content types in terms of its purposes.

1. Introduction

Digital solutions for marketing are taking their place with increasing power. There is no doubt as to the necessity to run digital marketing campaigns and activities, but it is about how to make them more efficient and consumer focused. Raising digital marketing concepts, such as inbound marketing and content marketing, causes the scientific issues of understanding consumers’ behavior while looking for appropriate content. Such an understanding is crucial for professionals who tend to adopt those two concepts in their companies. Content is the most important element not only in cases of an inbound or content marketing strategy, but also in all cases—social media marketing, email marketing, SEO, etc. It is the reason why a person uses the internet at all. Many sources analyze the phenomenon of digital content marketing, but only a few go deeply into the peculiarities of searching and consuming content in terms of marketing. Many authors state that content should be useful, relevant, and interesting, but there is a lack of knowledge on how the need for a specific type of content arises (Zhang et al. 2021; Štimac et al. 2021; Sun et al. 2022; Davidavičienė et al. 2020, 2021a, 2021b; Hsu and Chen 2018; Hollebeek and Macky 2019). This paper aims to reveal the source of reasons and triggers affecting content needs in the case of long-consumption products.

For the identification of consumer behavior peculiarities, such methods as literature analysis and synthesis were employed. Various theories of content values and user decision-making processes were analyzed, and a theoretical model of content need was formed. This model, which states that the need for a certain type of content emerges under the conditions of the consumer’s experienced gap of information or knowledge when in the stages of the buying model were tested after data were collected via a survey. The Cochran Q test and McNemar post hoc test were employed.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Content Purpose and Value

Defining digital content, i.e., assessing the purpose of the content, cannot be avoided either for whom or for what purpose it is designed or to meet the content-related needs of users. According to the purpose, the content can be divided into the following categories: (1) educational, (2) informational, and (3) entertaining (de Aguilera-Moyano et al. 2015). This classification of content, which helps to understand what types of content exist, is quite limited from the user’s perspective content evaluation, i.e., it does not answer the question of why the consumer will prefer the content of one or another publisher or brand. Additionally, content can match the attributes of several types of content at once, for example, being educational and entertaining at the same time, which in turn makes it difficult to understand how the consumer will react to the content after its consumption, as well as how the consumer’s relationship with the brand will be determined in the context of its perception and loyalty. In defining content marketing, it is noted that the content created and distributed must be valuable to the consumer (Hollebeek and Macky 2019; Content Marketing Institute 2020); as additionally (according to Lou and Xie 2021 and based on Schultz 2016; Hutchins and Rodriguez 2018; Ahmad et al. 2016), content marketing contributes significantly to brand development through the delivery of value to consumers, so the purpose of content can also be expressed in terms of value or values to the consumer. Lou and Xie (2021), based on (Ducoffe 1996) the theory of advertising value and (Sheth et al. 1991) the theory of consumption values and aggregating the value perception components of both, presented four value dimensions adapted to digital content—(1) informational, (2) entertainment value, (3) social value, and (4) functional value. They examined the impact of those values on consumer experiential brand appreciation theories and brand loyalty. They suggest defining content values as follows:

The informational value of content is the utility of providing new, timely, helpful, and valuable information about product/brand alternatives in making informed decisions (Ducoffe 1996).

The entertainment content value describes features designed to meet the entertainment needs of users (Ducoffe 1996).

The social value of content describes valuable content that helps to gain social benefits from a social network, such as popularity or similarity.

The functional value of content can capture how branded social media platforms or available media can be a reliable source of information (Ming-Sung Cheng et al. 2009).

By aggregating the value dimensions of different theories, the authors theorize that both the dimensions presented in advertising value theory (informational value and entertainment value) and the consumer value dimension (epistemic, emotional, social, functional, and conditional) can be compared and used to define the digital content value. In order to critically evaluate the results of aggregation and the possibilities of using the presented value dimensions in solving the dissertation problem, it is expedient to analyze in detail the logic of abstraction presented by the authors. Epistemic value, in consumption value theory, is defined as the benefit gained through consumer contact with new information and knowledge during consumption (Sheth et al. 1991). In advertising value theory, informational value is defined as the benefit of advertising in providing new, timely, useful, and valuable information about product/brand alternatives for making informed decisions (Ducoffe 1996). Lou and Xie (2021) assume that these concepts are identical and stick to the concept and definition of informational value. Emotional value refers to feelings or affective states associated with consumption choices (Sheth et al. 1991).

Similarly, the entertainment value of advertising value theory also captures the affective dimension and describes the functions of advertising in meeting consumer entertainment needs (Ducoffe 1996). According to (Sheth et al. 1991), social value defines the benefits of associating alternatives with one or more specific social groups. The addition of (Robertson 1967) the definition of social value—“perceived benefit associated with symbolic or fair consumption (e.g., clothing) or consumption shared with others (e.g., gifts) and often leading to interpersonal communication” concludes that the social value of branded content is defined as valuable content that helps a person obtain social benefits—such as polarity or liking—from their social network. Functional content value is defined as the perceived utility derived from the utilitarian or physical results of consumption choices (Sheth et al. 1991). Lou and Xie (2021) choose to define functional value in the context of their study as a value that can capture how branded social media platforms or managed media can be reliable sources of information (Ming-Sung Cheng et al. 2009). Conditional value, which is defined in consumption value theory as “the perceived utility that an alternative derives from a particular situation or circumstance faced by choice” (Sheth et al. 1991) is rejected by some researchers. They argue that conditional value is more a moderating factor influencing the perception of functional and social values than the independent value dimension (Sweeney and Soutar 2001) or that conditional value is a more special case of the remaining four values than the actual value dimension (Ming-Sung Cheng et al. 2009).

Despite the attractiveness of the value dimensions presented by Lou and Xie (2021) for evaluating digital content, some contradictions in conceptualizing those dimensions can also be seen. Theoretical considerations about the identity of epistemic and informational values are debatable. In a detailed analysis of (Sheth et al. 1991), the concept of epistemic value is observed in two components: “new information and knowledge gained through consumption.” Knowledge creation can be understood as a dynamic process in which data are collected and transformed into information that is later transformed into knowledge at different levels of learning (García-Fernández 2015). So, information and knowledge are not the same; rather, information is a means of acquiring knowledge, whereas learning is a prerequisite, as information is transformed into knowledge in the learning process. Information can be interpreted with some knowledge. Information becomes knowledge in the learning process.. Therefore, the epistemic value of the content, in the theory of consumption utility, and the informational value of the content, in the theory of advertising utility, cannot be equated to informational value alone. An equivalent transformation in the context of digital content value and for research purposes can be seen as the breakdown of epistemic value into informational and educational content value. “Relevant content permits you to sell. Content is the driving force behind the engagement effect from partner sites and outposts, content helps to engage in conversations and solve problems on social media, and content is the only way to be visible in search engines” (Chaffey and Smith 2017). Thus, content combines all the elements of inbound marketing into one whole, making content marketing a core activity of inbound marketing. Obviously, without appropriate and relevant content, all the channels used in the organization would be feature-only software. Unfortunately, the concept of relevant and appropriate content remains undefined, leading to the need for both theoretical discussion and empirical research. The relevance and appropriateness of the content to each user may likely be determined by some specific situation and also by the personal characteristics of the user.

2.2. Buying Model

While trying to reveal the triggers of consumer experienced content need, it is worth focusing on users’ buying behavior. Recently, researchers have been studying consumer behavior on the Internet from various aspects (Fu et al. 2020; Mishra et al. 2021; Lindh et al. 2020; Dang and Pham 2018; Reyes-Menendez et al. 2020; Wu and Yu 2020). Since the need for the content is assessed in the context of marketing and as a tool for customer satisfaction, we assume that the need for the content arises in the buying process. So, every stage that the consumer passes during that process can provoke demand for the special content.

One of the first purchasing decision-making models dates back to 1910, proposed by J. Dewey (Bruner and Pomazal 1988). This early model consisted of five steps (see Table 1). Subsequently, (Robinson et al. 1967) presented a grid or class model that described three types of purchasing situations: direct repurchase, modified repurchase, and new product purchase. The purchase decision is a process divided into several stages: need recognition, alternative assessment, alternative selection, and finally purchasing decision (Monat 2009). Following a series of studies, one of the most widely used five-step decision-making models, CDP (consumer decision process) was developed (Kotler and Keller 2016). The model defines user decision making from problem identification (need occurrence) to post-purchase behavior:

Table 1.

Factors affecting decision-making process of virtual teams.

- (1)

- Problem recognition;

- (2)

- Information search;

- (3)

- Evaluation of alternatives;

- (4)

- Buying decision;

- (5)

- Behavior after purchase.

Some authors analyzing the process and its application online suggest extending the model to six steps to include an additional “step in the purchasing process” (Chaffey and Ellis-Chadwick 2012). A comparison of the models is given in Table 1. In order to better understand the purchasing process, it is appropriate to analyze all its stages in more detail. Kotler’s five-step purchasing model, incorporating the “action” phase proposed by Chaffey, was chosen for a more detailed analysis.

Recognition of need (problem identification). The purchasing process begins with identifying the problem when the person realizes an unsatisfactory situation exists. Thus, by identifying the problem simultaneously, the consumer acknowledges the need to address it. Thus, a consumer’s purchasing decision is influenced by the problems faced (Jobanputra 2009). Need is the most important factor that drives the purchase of products or services. There are several types of problems: active problems, inactive problems, recognized, and unrecognized.

In practice, revealing and showing problems to consumers is a means of increasing sales when their obvious solutions are offered at the same time. Consumers’ efforts to find alternatives depend on various factors: market (number of competitors, brands), product characteristics (importance, quality), consumer characteristics (interest), etc.

Search of information. When a person admits that he or she needs a certain product or service, he or she tries to gather as much information about it as possible. The main task of marketers is to determine which sources of information have the most significant impact on their target market. At this evaluation stage, the customer has to choose between alternatives for brands, products, and services. The user can obtain information from such sources as the following:

- Personal: family, friends, neighbors, and so on.

- Commercial: sellers, advertisers, brokers, etc.

- Public: magazines, radio, newspapers, television, etc.

- Web: social networks, portals, search engines and so on.

- Experience: use, handling, analysis of a product or service.

The search for information may vary depending on the situation (Schoell and Guiltinan 1991). There are three levels of consumer decision making:

- Extended problem solving—a large amount of information is required;

- Limited solution—less information is needed because the consumer has already defined the product evaluation criteria but has not yet decided which alternatives to choose;

- Routine response behavior—a small amount of information is required, as the user experience with the product is already sufficient, and they can easily choose from many alternatives.

Evaluation of alternatives. Three types of assessment of alternatives are important in assessing which alternatives best meet the needs of the user, distinguished by the following:

- Comparative—The person in this state usually focuses on the technical details. They compare offers and choose the one they think is best. The key question at this stage is “is this the best option”?

- Implementation—A person focuses on the day-to-day use of goods or services. Usually, the consumer wants to know, “will this choice improve his daily life”?

- Results oriented—The decision is made only when the consumer is convinced that this choice will help to fulfill his obligations, improve and measure performance, i.e., increase profits or productivity, reduce operating costs, and increase competitive advantage. These people tend to ask themselves, “Will this help me get closer to X”?

In the context of information technology development and information availability, these stages become much more complex, creating new scientific challenges.

The decision to buy. The consumer finally acquires the product or service through the steps listed above.

Meanwhile, Dann and Dann (2011) single out five purchasing decision-making principles:

- Man is not a perfect decision maker because irrational behavior is easily predictable;

- When it comes time to make a decision, the consumer is looking for the easiest solution, relying on previous experience;

- People tend to make decisions as simple as possible, so they usually choose between similar options;

- The forces of default and complexity have a significant impact on decision making;

- The results of a decision can often be predicted and influenced.

Action. A well-presented incentive at this stage forces the consumer to “buy now” (Chaffey and Ellis-Chadwick 2012). The purchasing action and its timing are deliberate. The importance of this stage is emphasized in e-commerce.

Post purchasing behavior. After purchasing the product, the consumer undertakes an analysis—whether the decision was made correctly, i.e., whether the product was useful or met the needs and expectations of the user. Riley (Riley and Ungerleider 2012) argues that the post-purchase reaction manifests itself in cognitive dissonance; in judging the decision, the consumer thinks the alternative option would be better.

In summary, it can be said that all steps of buying decision model can trigger the need for content. The question is, what kind of content? At the beginning of the process, when the consumer is unaware of the problem that should be solved, thus there is no need for the product, the consumer will probably consume the entertainment content, which in turn can trigger the need for the product. In the search stage of the information, the consumer will probably look for informational and educational content. At the action stage, consumers can face uncertainties and phobias while using the e-shop, so there could be a focus on, for example, educational content.

3. Research Methodology

In order to identify the link between the consumers’ stage of the buying model and the need for a certain kind of content, the survey was conducted (data collection period was September–November 2021). The respondents were asked what type of content they need most while being in the specific stages of the buying decision model. The questionnaire was distributed using social media to random respondents. Three hundred thirty-six questionnaires were appropriately filled. Others were rejected because of various biases. The study was conducted in the context of consumer durables, as such products require deeper consumer involvement and more effort. The research was conducted in Lithuania. No specific industry was singled out in the study. Respondents were asked to imagine any durable relevant to them. It should be emphasized that content format preferences are not studied, nor are content search and consumption channel preferences, but only the content function expressed through the purpose of the content.

The extended 6-step buying decision-making model was employed in the research. It consists of the following steps: problem identification/needs identification, information search, comparison of alternatives, purchase decision, purchase process, and post-purchase behavior. The information retrieval phase was divided into two situations—information retrieval, knowing how to solve a problem, and information retrieval when encountering a problem for which the consumer is unaware of the product. Thus, in the final version, the stages of the purchasing decision were represented by seven situations. Respondents were asked to choose what kind of content is relevant to them (such content they will seek) in these situations. Content purpose categories include informational content (INF), educational content (EDU), entertainment content (PRAM), and interactive content (INT). So, the questionnaire consists of 10 questions. Three of them are intended to identify the demographic structure of the respondents. The seven questions are situations that define the user’s being at a specific stage of the purchase decision and the answer options, which consist of content types defined through the purpose of the content.

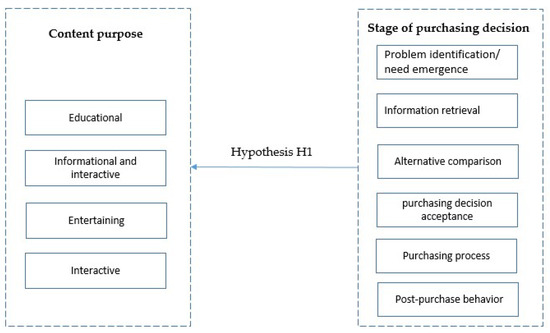

Hypothesis H1 was formulated: the existence of a statistically significant difference in consumers’ need for a particular content purpose (educational, informational, entertaining, and interactive) when the consumer is at a particular stage of purchasing decision (problem identification/need emergence, information retrieval, alternative comparison, purchasing decision acceptance, purchasing process, and post-purchase behavior) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors affecting consumer choice of web content.

The demographic data are presented in Table 2. The respondents consist of 21.1% males and 68.8% females. This show some limitations of results, considering that the male population is not represented in full scale.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristic respondents.

It can be concluded based on the sample analysis that females were more active and willing to participate in the research than men. It should also be noted that the most active group were those who were most educated (higher education 60.5%). The share distribution in the age category was relatively similar in the main groups (those with the most buying potential and needs).

4. Discussion of Results

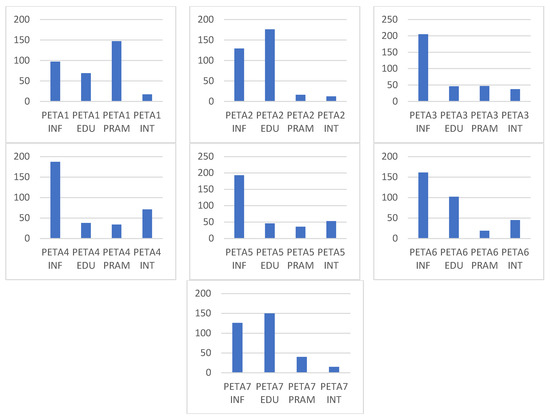

While analyzing received data, the need for informational content at all stages is clearly observed (see Figure 2). The least informational content is sought (compared to other stages) in the first stage when the consumer has not yet encountered a situation to be resolved. The need for educational content is clearly expressed in cases where the consumer is faced with a problem, the solution of which does not come from experience (PETA 2), or where it is necessary to learn how to use the products. In the first problem identification stage (PETA1), the consumer moves from a state where they do not understand that there is a problem to be solved by purchasing a particular product, to a state where the consumer understands the problem and takes action to address the problem.

Figure 2.

Distribution of preferred by respondents’ content in buying model stages.

At this stage, the content offered by the organization can help the user understand the problem, but it should be what the user expects. The research results show that the content most used in the problem identification phase is entertaining and the quite intensively used content of an informational and educational nature. The second stage of the purchasing decision model is the search for information divided into two components: when a consumer is faced with a problem where he/she does not know the product and method to solve (PETA2), and when he/she knows from experience the product that needs to be solved (PETA3). In the first case, there is a clear need for both informational and educational content. It should be noted that more respondents indicated educational content as the target at this stage. It is due to the fact that without knowing a specific product or facing a problem for the first time that cannot be solved from experience, the consumer is forced to learn how to solve that problem and what products are designed to solve it. When a consumer immediately recognizes the need to target a specific product, he or she focuses on searching for information about that product, such as technical product specifications, so in this case, the dominant content is informational. From the perspective of inbound marketing solutions for business organizations, this means that in cases where, for example, the product is innovative or non-widespread and unknown to the public, or where an organization’s products or groups of products are designed to address a consumer’s lifecycle, educational content covering the broadest possible range of consumer issues becomes essential. When comparing alternatives, the consumer focuses on informational content that may be dictated by the need to compare the specifications, features, and prices of different products. At this stage, the need for interactive or functional content emerges, i.e., consumers show an intention to look for convenient product comparison solutions. According to the distribution of the need for content, the purchase decision stage is very similar to the stage of comparison of alternatives analyzed earlier (no significant difference between the results is recorded). It can be explained by the assumption that the respondents perceive these two stages in the same way—after all, the decision to buy a particular product is the result of a comparison of alternatives, so the consumer’s decision to buy can be treated in the same way as a comparison of alternatives. At the purchasing stage, consumers take active steps to purchase the product for which a decision has been made. By linking the need for content use with this stage, respondents single out the need for educational content alongside information content. At this stage, consumers are likely to face, for example, certain uncertainties and fears related to e-shop functions. This, in turn, forces the consumer to look for content that can help eliminate those uncertainties and teach how to use one feature or another. After purchasing, consumers face cognitive dissonance challenges and challenges related to product operation, so the need for educational content is also evident at this stage, and the need for entertaining content is growing.

Hypothesis H1 assesses the existence of a statistically significant difference in consumers’ need for a particular content purpose: educational, informational, entertaining, and interactive when the consumers are at a particular stage of their purchasing decision: problem identification/need emergence, information retrieval, alternative comparison, purchasing decision acceptance, purchasing process, and post-purchase behavior. For this purpose, Cochran’s Q test is used, with H0, success rate equal to all study groups, and H1, a success rate that differs in at least one group. The study found (see Table 3) that at all stages of the purchasing decision, statistically significant differences are recorded in the purpose of the intended content, so H0 is rejected and H1 is accepted, confirming H1.

Table 3.

The results of Qochran’s Q test.

In summary, Hypothesis H1, the presence of consumers at a particular stage of the purchasing decision determines the purpose of the intended content, is confirmed. In the context of inbound marketing, the reasons for users’ activity in pursuing one type or another of online content are crucial.

The source of these reasons may be the state of the consumer, in which the consumer seeks or may seek information and knowledge in the form of digital content that confers some of the uncertainties to be addressed. Thus, the extended six-step purchasing decision model essentially explains the origin of volume demand expressed through the content purpose in the context of inbound marketing and can be used to model traffic to a business organization’s website, but the insights gained from the study need to be considered. The information retrieval phase must be divided into two components, characterized by situations in which (a) the user identifies a problem in the demand recognition phase for which the solution or measures are not known, and (b) the consumer identifies a problem for which the product needs to be identified, and the need is immediately recognizable. At these stages, differences are observed for all content uses. It should be noted that in the case of the PETA4-PETA5 stages, there is no significant difference in the intensity of the demand for content in all cases (INF, EDU, PRAM, and INT), which means that, as mentioned above, organizations only need to consider the specifics of the alternative comparison phase when creating content to meet the demand for content in the purchasing stages.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of the literature showed that content marketing and thus content itself is an essential element of inbound marketing. The different value theories state that content, just like anything else, has its own value to the consumer, and value has predefined dimensions. This research is based on the assumption that content values defined in the literature are not perceived in that way at the very beginning of a consumer’s activity related to content search and consumption but rather are perceived as a purpose of the content. Based on theoretical research, four content purposes that the consumer can perceive were clarified—informational, educational, entertaining, and interactive content.

On the other hand, after analyzing the user’s buying decision models, the extended 6-stage model was chosen for the research as explaining the origins of the consumer’s need for content.

The empirical research showed that there is a relationship between the consumer’s presence in the stages of buying decision model and content purpose, and that model can be employed as a base for the explanation of content need origins in terms of inbound marketing. It should be noted that some insights should be considered: (1) The information search stage must be divided into two considering different situations, the one where the consumer faces a problem that cannot be solved based on the past experience of the consumer and where the consumer knows what product solves the recognized problem. (2) The test applied in this research reveals significant differences when comparing different situations all at once. It does not compare the need for different content types in pairs of stages of buying model, so additional research and analysis of the data are needed.

A limitation of the study is that the study was conducted in the context of consumer durables without identifying a specific industry. This determines the need to expand research by narrowing the context in the sense of specifying the industry.

For further research and a more detailed scope and understanding of the web content needs, it is necessary to study the factors that determine the need for specific content at each stage of the purchase decision, as well as areas of interest of consumers that impact the demand for certain content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D.; Formal analysis, S.D.; Investigation, S.D.; Methodology, S.D.; Resources, S.D.; Supervision, T.L.; Validation, T.L.; Writing—original draft, S.D.; Writing—review and editing, T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, Nur Syakirah, Rosidah Musa, and Mior Harris Mior Harun. 2016. The Impact of Social Media Content Marketing (SMCM) towards Brand Health. Procedia Economics and Finance 37: 331–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruner, Gordon C., and Richard J. Pomazal. 1988. Problem Recognition: The Crucial First Stage of the Consumer Decision Process. Journal of Services Marketing 2: 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffey, Dave, and Fiona Ellis-Chadwick. 2012. Digital Marketing: Strategy, Implementation and Practice. London: Pearson, Available online: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Digital-Marketing-Strategy-Implementation-Practice/dp/0273746103 (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Chaffey, Dave, and Paul Russell Smith. 2017. Digital Marketing Excellence: Planning, Optimizing and Integrating Online Marketing, 5th ed. London: Routledge, vol. 690. [Google Scholar]

- Content Marketing Institute. 2020. What Is Content Marketing? Available online: https://contentmarketinginstitute.com/what-is-content-marketing/ (accessed on 21 February 2021).

- Dang, Van Thac, and Thuy Linh Pham. 2018. An Empirical Investigation of Consumer Perceptions of Online Shopping in an Emerging Economy: Adoption Theory Perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 30: 952–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, Stephen, and Susan Dann. 2011. E-Marketing Theory and Application. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, Available online: https://books.google.lt/books/about/E_Marketing.html?id=GCDINtIqY2sC&redir_esc=y (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Davidavičienė, Vida, Olena Markus, and Sigitas Davidavičius. 2020. Identification of the Opportunities to Improve Customer’s Experience in E-Commerce. Journal of Logistics, Informatics and Service Science 7: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidavičienė, Vida, Jurgita Raudeliūnienė, and Rima Viršilaitė. 2021a. Evaluation of User Experience in Augmented Reality Mobile Applications. Journal of Business Economics and Management 22: 467–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidavičienė, Vida, Raudeliūnienė Jurgita, Jonytė-Zemlickienė Akvilė, and Tvaronavičienė Manuela. 2021b. Factors Affecting Customer Buying Behavior in Online Shopping. Marketing and Management of Innovations 4: 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Aguilera-Moyano, Joaquín, Miguel Baños-González, and J. Ramírez-Perdiguero. 2015. Branded Entertainment: Entertainment Content as Marketing Communication Tool. A Study of Its Current Situation in Spain. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 70: 519–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ducoffe, Robert H. 1996. Advertising Value and Advertising on the Web. Journal of Advertising Research 36: 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Hanliang, Gunasekaran Manogaran, Kuang Wu, Ming Cao, Song Jiang, and Aimin Yang. 2020. Intelligent Decision-Making of Online Shopping Behavior Based on Internet of Things. International Journal of Information Management 50: 515–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, Mariano. 2015. How to Measure Knowledge Management: Dimensions and Model. VINE 45: 107–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, Linda D., and Keith Macky. 2019. Digital Content Marketing’s Role in Fostering Consumer Engagement, Trust, and Value: Framework, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications. Journal of Interactive Marketing 45: 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Chia Lin, and Mu Chen Chen. 2018. How Does Gamification Improve User Experience? An Empirical Investigation on the Antecedences and Consequences of User Experience and Its Mediating Role. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 132: 118–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, Jennifer, and Darlene Xiomara Rodriguez. 2018. The Soft Side of Branding: Leveraging Emotional Intelligence. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 33: 117–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobanputra, Kuldeep. H. 2009. Global Marketing and Customer Decision Making. Maharashtra: Paradise. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, Philip, and Kevin Lane Keller. 2016. Marketing Management. Marketing Management. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Lindh, Cecilia, Emilia Rovira Nordman, Sara Melén Hånell, Aswo Safari, and Annoch Hadjikhani. 2020. Digitalization and International Online Sales: Antecedents of Purchase Intent. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 32: 324–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lou, Chen, and Quan Xie. 2021. Something Social, Something Entertaining? How Digital Content Marketing Augments Consumer Experience and Brand Loyalty. International Journal of Advertising 40: 376–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming-Sung Cheng, Julian, Edward Shih-Tse Wang, Julia Ying-Chao Lin, and Shiri D. Vivek. 2009. Why Do Customers Utilize the Internet as a Retailing Platform?:A View from Consumer Perceived Value. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 21: 144–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Ruchi, Rajesh Kumar Singh, and Bernadett Koles. 2021. Consumer Decision-Making in Omnichannel Retailing: Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies 45: 147–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monat, Jamie P. 2009. Why Customers Buy. Marketing Research 201: 20–24. Available online: https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=932722dd-cf89-48b6-bdaa-f1ec02d6a246%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#db=bsu&AN=37012066 (accessed on 18 December 2020).

- Reyes-Menendez, Ana, Marisol B. Correia, and Nelson Matos. 2020. Understanding Online Consumer Behavior and Ewom Strategies for Sustainable Business Management in the Tourism Industry. Sustainability 12: 8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, Tasha, and Charles Ungerleider. 2012. Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: How Teachers’ Attributions, Expectat. Canadian Journal of Education 35: 303–33. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Thomas S. 1967. The Process of Innovation and the Diffusion of Innovation. Journal of Marketing 31: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Patrick J., Charles W. Faris, and Yoram Wind. 1967. Industrial Buying and Creative Marketing. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, Available online: https://books.google.lt/books?id=vBtPAAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_book_other_versions (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Schoell, William F., and Joseph P. Guiltinan. 1991. Marketing: Contemporary Concepts and Practices. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, p. 781. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, Don. 2016. The Future of Advertising or Whatever We’re Going to Call It. Journal of Advertising 45: 276–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, Jagdish N., Bruce I. Newman, and Barbara L. Gross. 1991. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. Journal of Business Research 22: 159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štimac, Helena, Ivan Kelić, and Karla Bilandžić. 2021. How Web Shops Impact Consumer Behavior? Tehnički Glasnik 15: 350–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Yuan, Yating Zhong, and Qi Li. 2022. Online Communities and Offline Sales: Considerations on Visiting Behavior Dimensions and Online Community Types. Industrial Management and Data Systems 122: 1620–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, Jillian C., and Geoffrey N. Soutar. 2001. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. Journal of Retailing 77: 203–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I. Chin, and Hsin Kai Yu. 2020. Sequential Analysis and Clustering to Investigate Users’ Online Shopping Behaviors Based on Need-States. Information Processing and Management 57: 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Xi, Hongda Liu, and Pinbo Yao. 2021. Research Jungle on Online Consumer Behaviour in the Context of Web 2.0: Traceability, Frontiers and Perspectives in the Post-Pandemic Era. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16: 1740–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).