Informal Learning with a Gender Perspective Transmitted by Influencers through Content on YouTube and Instagram in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Identify indicators of cyberfeminist practices among Spanish influencers

- Demonstrate the socio-educational importance of cyberfeminism.

2.1. Analysis Units and Sample Type

2.2. Content Analysis Categories

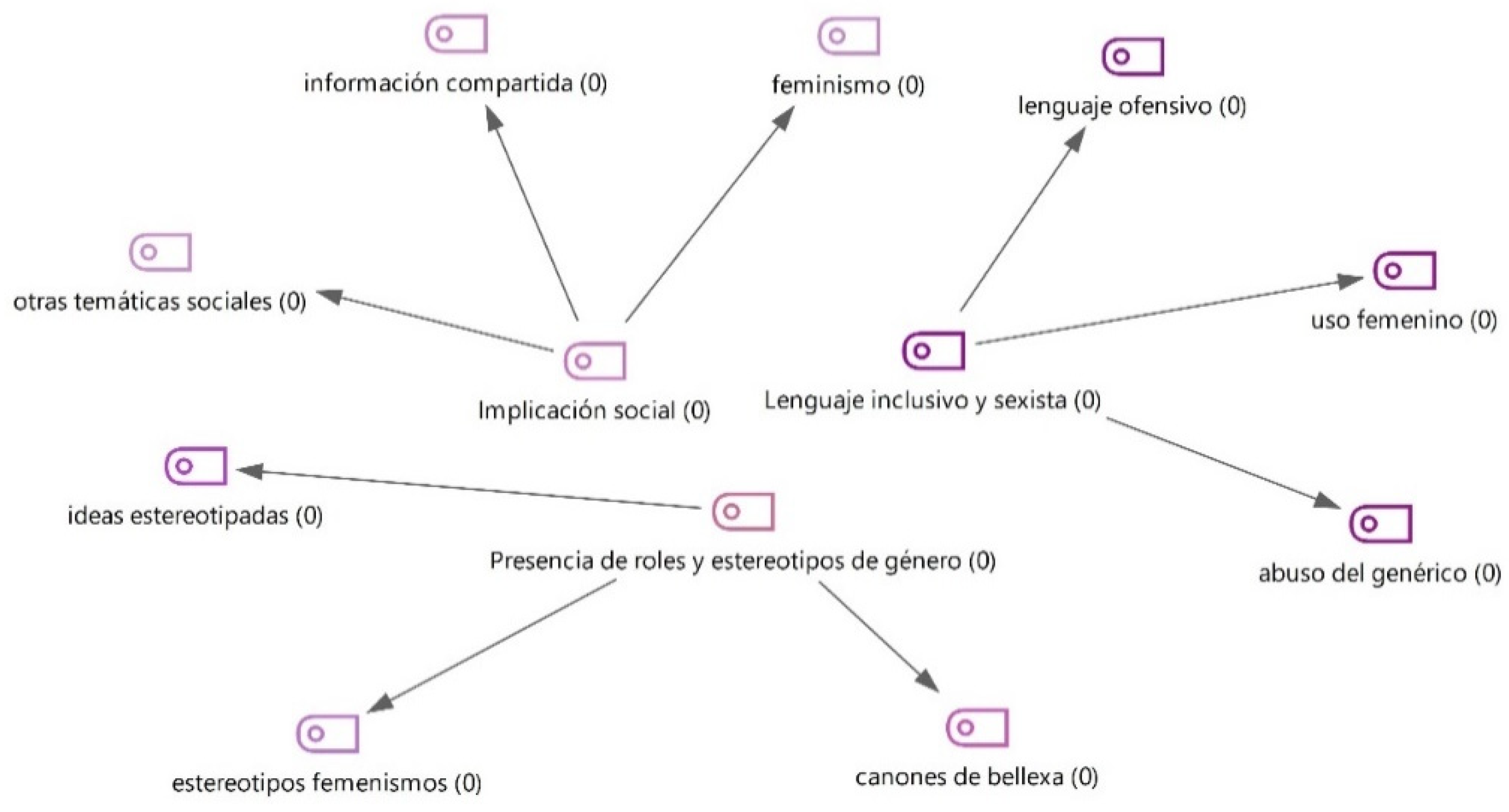

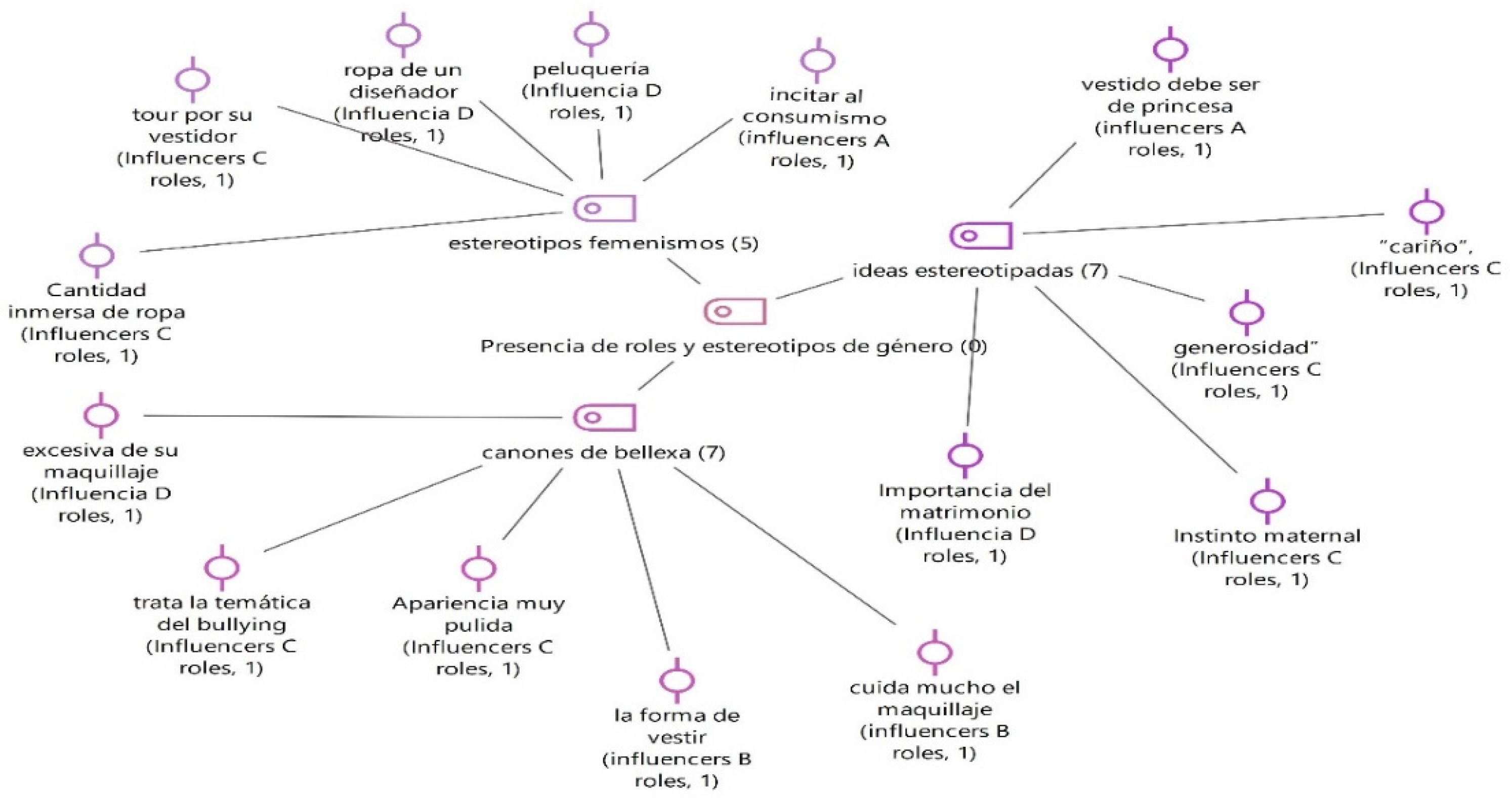

- Gender roles and stereotypes: We live in a society that dictates symbolically what we are or should be as men and women. The socially constructed images and stereotypes to which we are exposed from birth shape the way we think and behave as adults (Iglesias and Sánchez-Bello 2008). The main indicators in this category are socially established beauty standards; recommendations based on female stereotypes (e.g., clothes, makeup, etc.); and patriarchal stereotypes about women (see Figure 1).

- Sexist or inclusive language: Language reflects collective thinking and transmits the feelings, thoughts, and actions of a society (Moreno 2000), and the system on which it is based. The main indicators in this category are overuse of generic language (i.e., mainly masculine forms); low occurrence of feminine forms; and the presence of offensive or disrespectful language. While not directly related to sexist language, the final indicator is based on the principle that social media content should be educational and helpful (see Figure 1).

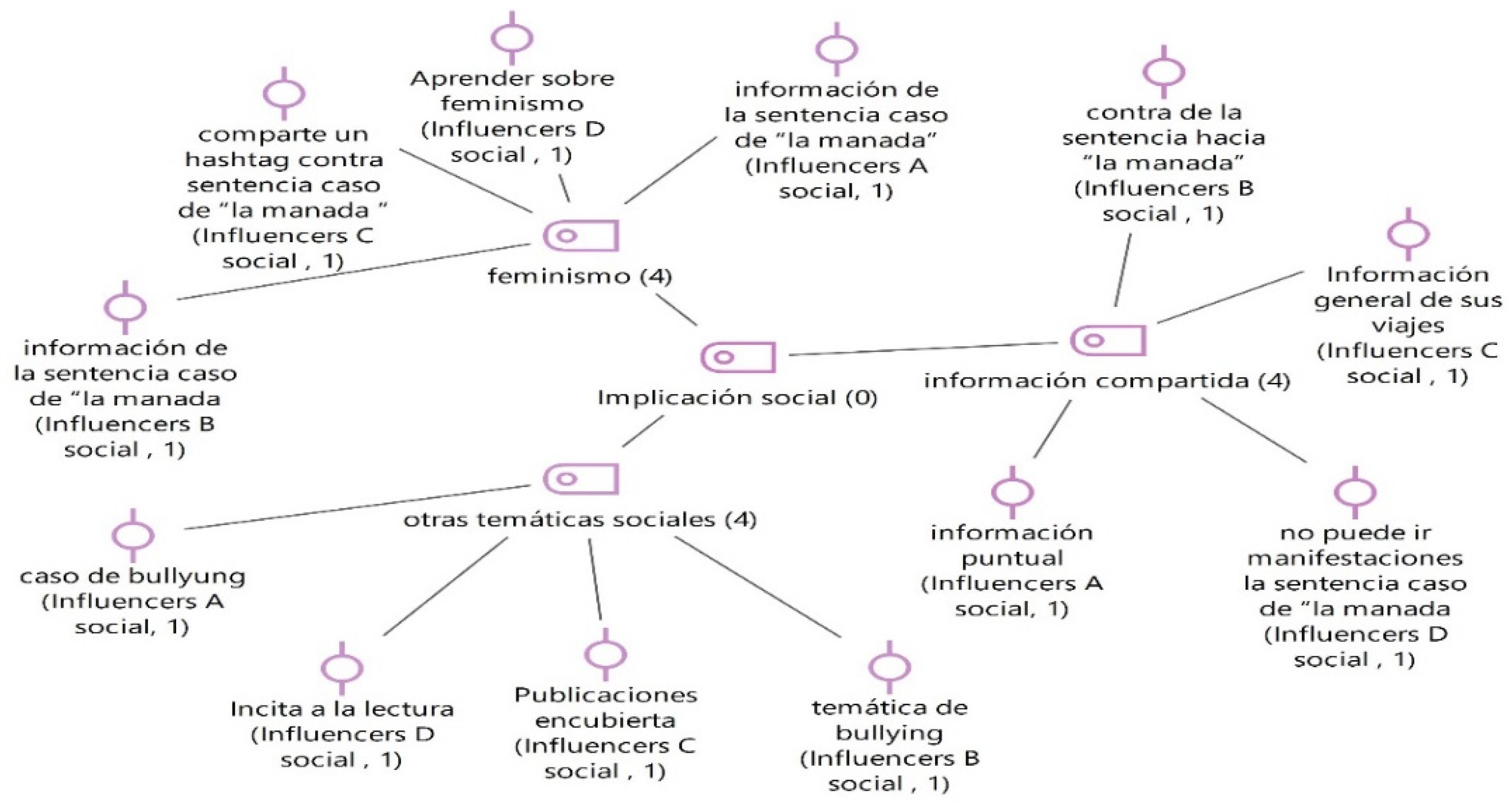

- Social engagement with issues related to feminist activism and gender equality movements online: This dimension does not deal directly with gender inequalities in society and the ways in which we unconsciously sustain them, but instead focusses on the need for an engaged cyberfeminism. The main indicators in this category are sharing of information related to feminism; involvement in the information shared on their social media; and sharing of useful information on other social issues (see Figure 1).

2.3. Information Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Gender Roles and Stereotypes

3.2. Sexist or Inclusive Language

3.3. Social Engagement

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Schugurensky (2000) divides informal education into three categories: self-directed learning, incidental learning, and socialisation. In this study, we use the term ‘informal education’ as a synonym of socialisation. |

| 2 | As the analysis is about influencers’ material in Spanish, the comments of the figures appear in this language but with a footnote with the English translation. In this way, we do not lose the expressions of the source language. |

| 3 | Terms that appear in Figure 1 (following the order of the dimensions that appear in the “Content analysis categories” section): (a) presence of gender roles and stereotypes (“presencia de roles y estereotipos de género”): stereotyped ideas (“ideas estereotipadas”); stereotyped feminisms (“estereotipos feminismos”) and canons of beauty (“canonces de belleza”); (b) inclusive and sexist language (“lenguaje inclusivo y sexista”): offensive language (“lenguaje ofensivo”); feminine use (“uso femenino”) and abuse of the generic (“abuso del genérico”) and c)social implication (“implicación social”): feminism (“feminismo”); shared information (“información compartida”) and other social issues (“otras temáticas sociales”). |

| 4 | Terms that appear in Figure 2 (taking into account the dimension and the categories that appear in Figure 1. The dimension is Presence of gender roles and stereotypes (“presencia de roles y estereotipos de género”)): (a) canons of beauty (“canones de belleza”): excessive makeup (“excesiva de su maquillaje”); deals with the issue of bullying (“trata la temática del bullying”); highly polished appearance (“apariencia muy pulida”); the way of dressing (“la forma de vestir”) and takes great care of the makeup (“cuida mucho el maquillaje”); (b) stereotyped ideas (“ideas estereotipadas”): dress must be princess (“vestido debe ser de princesa”); sweetie (“cariño”); generosity (“generosidad”); maternal instinct (“instito maternal”) and importance of marriage (“importancia del matrimonio”) and c) feminist stereotypes (“estereotipos feminismo”): Incite consumerism (“iniciar al comsumismo”); hairdressing (“peluquería”); designer clothes (“ropa de un diseñador”); tour of her dressing room (“tour por su vestidor”) and immense amount of clothes (“cantidad inmensa de ropa”). |

| 5 | Terms that appear in Figure 3 (bearing in mind the dimension and the categories that appear in Figure 1. The dimension is inclusive and sexist language (“lenguaje sexista e inclusivo”)): (a) feminine use (“uso femenino”): people (“personas”); reucrre often to the generic (“recurre a menudo al generico”); term “guys” (“ termino “guys”“); their thoughts (“sus pensamientos”) and people (“gente”); (b) offensive language (“lenguaje ofensivo”): funcking (“funcking”) and (c) abuse of the generic (“abuso del genérico”): (a) inclusive language (“lenguaje inclusivo”); use English (“utiliza el inglés”); readers (“lectores”); everyone (“todos”) and you (“vosotros”). |

| 6 | Terms that appear in Figure 4 (bearing in mind the dimension and the categories that appear in Figure 1. The dimension is social implication (“implicación social”)): (a) feminism (“feminismo”): information on the sentence case of “the herd “ (“información de la setencia caso de “la manada””); learn about feminism (“aprender sobre el feminismo”); share your hashtag against the sentence case of “the herd”(“comparte un hastag contra setencia caso de “la manada”); (b) shared information (“información compartida”): against the sentence towards “the herd” (“contra de la sentencia hacia “la manada”); general information about your trips (“informacion general de sus viajes”); you cannot attend demonstrations in the case of “the herd” (“no puede ir manifestaciones la setencia caso de “la manada”“) and specific information (“información puntual”) and c) other social issues (“otras temáticas sociales”): (a) case of bullying (“caso de bullying”); encourage reading (“incita a la lectura”); covert posts (“publicaciones encubierta”) and bullying themed (“tematica de bullying”). |

| 7 | For example, whereas in the Spanish phrase ‘la mujer buena y el hombre bueno’, the adjective bueno/a is marked for gender according to the sex (and gender) of the noun, in the English equivalent, there is no distinction between the adjectives associated with each noun: ‘the good woman and the good man’. |

References

- Ackerman, Lauren M. 2019. Syntactic and cognitive issues in investigating gendered coreference. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 4: 5–27. Available online: https://www.glossa-journal.org/article/id/5224 (accessed on 19 April 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andreu, Jaime. 2002. Las Técnicas de Análisis de Contenido: Una Revisión Actualizada. Sede de Sevilla: Fundación Centro de Estudios Andaluces, Available online: https://bit.ly/3BTot0A (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Arab, L. Elías, and Alejandra Díaz. 2015. Impacto de las redes sociales e internet en la adolescencia: Aspectos positivos y negativos. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes 26: 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aran-Ramspott, Sue, Maddalena Fedele, and Anna Tarragó. 2018. Youtubers’ social functions and their influence on pre-adolescence. [Funciones sociales de los youtubers y su influencia en la preadolescencia]. Comunicar 26: 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araüna, Núria, Cilia Willem, and Iolanda Tortajada Giménez. 2019. Discursos feministas y vídeos de youtubers: Límites y horizontes de la politización yo-céntrica. Quaderns del CAC 45: 25–34. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7074189 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Árdevol, Elisend, and Edgar Gómez. 2012. Las Tecnologías Digitales en el Proceso de Investigación Social: Reflexiones Teóricas y Metodológicas Desde la Etnografía Virtual. Cataluña: Fundación CIDOB (Spain), Available online: https://www.cidob.org/es/articulos/monografias/politicas_de_conocimiento_y_dinamicas_interculturales_acciones_innovaciones_transformaciones/las_tecnologias_digitales_en_el_proceso_de_investigacion_social_reflexiones_teoricas_y_metodologicas_desde_la_etnografia_virtual (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Ardila, Erwin Esaú, and Juan Felipe Rueda Arenas. 2013. La saturación teórica en la teoría fundamentada: Su delimitación en el análisis de trayectorias de vida de víctimas del desplazamiento forzado en Colombia. Revista Colombiana de Sociología 36: 93–114. Available online: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/recs/article/view/41641 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Barry, Christine A., Nicky Britten, Nick Barber, Colin Bradley, and Fiona Stevenson. 1999. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research 9: 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begoechea, Mercedes. 2015. Lengua y Género. Madrid: Madrid Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos, Edixela Karitza. 2017. El Ciberactivismo: Perspectivas conceptuales y debates sobre la movilización social y política. Revista Contribuciones a las Ciencias Sociales, 1–5. Available online: http://www.eumed.net/rev/cccss/2017/02/ciberactivismo.html (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Casado, Carla, and Xavier Carbonell. 2018. La influencia de la personalidad en el uso de Instagram. Aloma: Revista de Psicologia, Ciències de L’educació i de L’esport 36: 23–31. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/La-influencia-de-la-personalidad-en-el-uso-de-Riera-Carbonell/525ef8701e97eee1225b566c579ca9675a709255 (accessed on 19 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Casero-Ripollés, Andreu. 2015. Estrategias y prácticas comunicativas del activismo político en las redes sociales en España. Historia y Comunicación Social 20: 535–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castells, Manuel. 2009. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cobo, Rosa. 2019. Cuarta ola feminista y la violencia sexual. Paradigma: Revista Universitaria de Cultura 22: 134–38. Available online: https://bit.ly/3DMxp8G (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Colás-Bravo, Pilar, and Iván Quintero-Rodríguez. 2022. YouTube como herramienta para el aprendizaje informal. Profesional de la Información 31: 310–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Piqueras, Cristina, María José González Moreno, and Juan Carlos Checa Olmos. 2021. ¿Empoderadas u objetivadas? Análisis de las ciberfeminidades en las influencers de moda. Investigaciones Feministas 12: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curbelo, Dayana, and Natalia Moreira. 2016. Adolescentes y tecnologías en el aula. Un análisis desde la perspectiva de género. Congreso Iberoamericano de Ciencia, Tecnología, Innovación y Educación 487: 1–22. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/10793801/Adolescentes_y_tecnolog%C3%ADas_en_el_aula_An%C3%A1lisis_desde_la_perspectiva_de_g%C3%A9nero (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- da Silva, Cleilton Alves, and Carlos Ferreira. 2016. Las redes sociales y el aprendizaje informal de estudiantes de educación superior. Acción Pedagógica 25: 6–20. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6224935 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Demirhan, Kamil, and Derya Çakır-Demirhan. 2015. Gender and politics: Patriarchal discourse on social media. Public Relations Review 41: 308–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso-Vázquez, Trinidad. 2018. Perspectiva de género en la Universidad como motor de innovación. In La Universidad en Clave de Género. Edited by Angeles Rebollo-Catalán, Esther Ruíz and Luisa Vega-Caro. Barcelona: Ediciones Octaedro, pp. 23–52. Available online: https://bit.ly/2XnPKcI (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Elorriaga Illera, Angeriñe, and Sergio Monge Benito. 2018. La profesionalización de los youtubers: El caso de Verdeliss y las marcas. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social 73: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Escandell-Vidal, Victoria M. 2018. Reflexiones sobre el género como categoría gramatical. Cambio ecológico y tipología lingüística. In De la Lingüística a la Semiótica: Trayectorias y Horizontes del Estudio de la Comunicación. Edited by Maria Ninova. Sofia: Bulgaria Universidad San Clemente de Ojrid, pp. 1–28. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326583738_REFLEXIONES_SOBRE_EL_GENERO_COMO_CATEGORIA_GRAMATICAL_CAMBIO_ECOLOGICO_Y_TIPOLOGIA_LINGUISTICA (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Fernández, Flory. 2002. El análisis de contenido como ayuda metodológica para la investigación. Revista Ciencias Sociales 2: 35–53. Available online: https://bit.ly/3n0eSz0 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Flick, Uwe. 2012. Introducción a la Investigación Cualitativa. Barcelona: Morata. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Márques de Oliva. 2021. Los 50 Influencersmmás Importantes de España. Madrid: Madrid Fundación Márques de Oliva, Available online: https://fundacionmarquesdeoliva.com/estudio-de-los-500-espanoles-mas-influyentes-de-2021/los-50-influencers-mas-importantes-de-espana-en-2021/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Fundación Telefónica. 2018. Sociedad Digital en España 2017. Madrid: Madrid Fundación Telefónica España, Available online: https://bit.ly/30tnmH7 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- García, Almudena. 2007. Cyborgs, mujeres y debates. El ciberfeminismo como teoría crítica. Barataria. Revista Castellano-Manchega de Ciencias Sociales 8: 13–26. Available online: https://bit.ly/3aRoE0t (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Harris, James W. 1991. The exponence of gender in Spanish. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 27–62. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4178707?origin=JSTOR-pdf#metadata_info_tab_contents (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Hwang, Sungsoo. 2007. Utilizing qualitative data analysis software: A review of ATLAS.ti. Social Science Computer Review 26: 519–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAB Spain. 2019. Marketing de Influencers. Libro Blanco. Madrid: IAB Spain, Available online: https://www.amic.media/media/files/file_352_2145.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- IAB Spain. 2021. Estudio Anual de Redes Sociales 2021. Madrid: IAB Spain, Available online: https://bit.ly/3AJKFcp (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Iglesias, Ana, and Ana Sánchez-Bello. 2008. Currículum oculto en el aula, estereotipos en acción. In Educar en la Ciudadanía: Perspectivas Feministas. Edited by Rosa Cobo. Barcelona: La Catarata, pp. 123–50. Available online: https://bit.ly/3vmC5yV (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Influencer MarñetingHub. 2022. El Estado de Marketing de Influencers 2022: Informe de Referencia. Influencer MarñetingHub. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report/ (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). 2021. Equipamiento y uso de TIC en los Hogares 2020. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), Available online: https://bit.ly/3BRNV6G (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Jiang, Shaohai, and Annabel Ngien. 2020. The effects of Instagram use, social comparison, and self-esteem on social anxiety: A survey study in Singapore. Social Media + Society 6: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, Jessalynn, Kaitlynn Mendes, and Jessica Ringrose. 2016. Speaking “unspeakable things”; documenting digital feminist responses to rape culture. Journal of Gender Studies 27: 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macharia, Sarah. 2015. Who Makes the News? Global Media Monitoring Project (GMMP). Toronto: WACC. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, María Teresa, and María Yolanda Martínez. 2019. Mujeres ilustradoras en Instagram: Las influencers digitales más comprometidas con la igualdad de género en las redes sociales/Women illustrators on Instagram: Digital influencers more committed to gender equality in social networks. Revista Internacional de Cultura Visual 6: 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos, Sara, and Clara Gómez. 2019. Libro Blanco de la Mujer en el Ámbito Tecnológico; Madrid: Ministerio de Economía y Empresa. Available online: https://bit.ly/3j5U6g8 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Miles, Mateo, Michael Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis. A Methods Sourcebook. New York: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Energía, Turismo y Agenda Digital. 2020. La sociedad en Red. Transformación digital en España. Informe Anual 2019; Madrdid: Ministerio de Energía, Turismo y Agenda Digital. Available online: https://bit.ly/3lNR2qM (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Moreno, Montserrat. 2000. Cómo se Enseña a ser Niña: El Sexismo en la Escuela, 3rd ed. Madrid: Icaria. [Google Scholar]

- Mujeres en Red. 2001. Las cyborgs. Ciberfeminismo. Mujeres en Red 8: 1–5. Available online: https://bit.ly/3aIlFHO (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Núñez, Sonia, and María Hernández. 2011. Prácticas Para el Ciberfeminismo. Uso de Identidades en la Red Como Nuevo Espacio de Comunicación. Madrid: Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. [Google Scholar]

- Odriozola, Javier. 2012. Análisis de contenido de los cibermedios generalistas españoles. Características y adscripción temática de las noticias principales de portada. Comunicación y Sociedad 25: 279–304. Available online: https://bit.ly/3BPqkDz (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura (UNESCO). 2019. Recomendaciones Para Un Uso No Sexista del Lenguaje. New York: UNESCO, Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000114950 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Organización de Naciones Unidas (ONU). 2019. Lenguaje Inclusivo en Cuanto al Género. New York: Organización de Naciones Unidas, Available online: https://www.un.org/es/gender-inclusive-language/guidelines.shtml (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Padilla, Graciela, and Ana Belén Oliver. 2018. Instagramers e influencers. El escaparate de la moda que eligen los jóvenes menores españoles. Revista Internacional de Investigación en Comunicación 18: 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, Inmaculada. 2016. Género y tecnologías. Ciberfeminismos y construcción de la tecnocultura actual. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias, Tecnología y Sociedad 11: 171–93. Available online: https://bit.ly/3aNbxOa (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Pérez-Torres, Vanessa, Yolanda Pastor-Ruiz, and Sara Abarrou-Ben-Boubaker. 2018. Youtuber videos and the construction of adolescent identity. [Los youtubers y la construcción de la identidad adolescente]. Comunicar 26: 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popa, Dorin, and Delia Gavriliu. 2015. Gender Representations and Digital Media. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 180: 1199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Postill, John. 2018. The Rise of Nerd Politics. Digital Activism and Political Change. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reece, Andréz G., and Christopher M. Danforth. 2017. Instagram photos reveal predictive markers of depression. Epj Data Science 6: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez, Alicia Arias, and Ana Sánchez Bello. 2017. La cimentación social del concepto mujer en la red social Facebook. Revista de Investigación Educativa 35: 181–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez, Carmen. 2011. Género y Cultura Escolar. Barcelona: Morata. [Google Scholar]

- Rovira, Guiomar. 2017. Activismo en red y Multitudes Conectadas. Madrid: Icaria. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, Ana. 2016. El lenguaje y la igualdad efectiva de mujeres y hombres. Revista Bioética y Derecho 38: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruíz, Margarita. 2016. Sexismo en Línea. WhatsApp, Nuevo Mecanismo de Reproducción del Sexismo. Jaén: Diputación de Jaén. [Google Scholar]

- Sainz, Milagros, Lidia Arrojo, and Celia Castaño. 2020. Mujeres y Digitalización. De las Brechas a los Algoritmos. Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer y para la Igualdad de Oportunidades, Available online: https://bit.ly/3FTbPkI (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Sainz, Milagros. 2007. Aspectos Psicosociales de las Diferencias de Género en Actitudes Hacia las Nuevas Tecnologías en Adolescentes. Doctoral thesis, Madrid Injuve, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Salcines-Talledo, Irina, Antonia Ramírez-García, and Natalia González-Fernández. 2018. Smartphones y tablets en familia. Construcción de un instrumento diagnóstico. Aula Abierta 47: 265–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Duarte, José-Manuel, and Diana Fernández-Romero. 2017. Subactivismo feminista y repertorios de acción colectiva digitales. Prácticas ciberfeministas en Twitter. El Profesional de la Información 26: 894–902. Available online: https://bit.ly/30pJJgC (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Sandín, María Paz. 2000. Criterios de validez en la investigación cualitativa: De la objetividad a la solidaridad. Revista de Investigación Educativa 18: 223–42. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/rie/article/view/121561 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Santamaría, Elena, and Rufino Meana. 2017. Redes sociales y ‘fenómeno influencer’ reflexiones desde una perspectiva psicológica. Miscelánea Comillas: Revista de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales 75: 443–69. Available online: https://bit.ly/3APU2HB (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Santiago, Michael, Cristina Permisan, and Manuel Francisco Romero. 2019. Consulta a docentes del Máster de Profesorado de Secundaria sobre la alfabetización mediática e informacional (AMI). Diseño y validación del cuestionario. Revista Complutense De Educación 30: 1045–66. Available online: https://bit.ly/3aHxP3M (accessed on 19 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Marco, Paloma, Gloria Jiménez-Marín, and Rodrígo Elias Zambrano. 2019. La imcorporación de la figura del influencer en la campaña pubicitaria. Consecuencias para la agencia de publicidad españolas. Revista de Estrategia, Tendencia e Innovación en Comunicación 18: 63–86. [Google Scholar]

- Schugurensky, Daniel. 2000. The Forms of Informal Learning. Towards a Conceptualization of the Field; London Centre for the study of Education and Labor, OISE/UT. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1807/2733 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Simkin, Hugo, and Gastón Becerra. 2013. El proceso de socialización. Apuntes para su exploración en el campo psicosocial. Ciencia, Docencia y Tecnología 14: 119–42. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4696738 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Sokolova, Karinam, and Charles Perez. 2021. You follow fitness influencers on YouTube. But do you actually exercise? How parasocial relationships, and watching fitness influencers, relate to intentions to exercise. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 58: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treré, Emiliano. 2012. Social movements as information ecologies: Exploring the coevolution of multiple Internet technologies for activism. International Journal of Communication 6: 2359–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, Zeynep. 2013. ‘Not This One’ Social Movements, the Attention Economy, and Microcelebrity Networked Activism. American Behavioral Scientist 57: 848–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcárcel, Amelia. 2000. La memoria colectiva y los retos del feminismo. In Los Desafíos del Feminismo Ante el Siglo XXI. Edited by Rocio Romero and Amelia Valcárcel. Madrid: Hypatia, pp. 19–54. Available online: https://bit.ly/3FU9kP9 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Varela, Nuria. 2020. El tsunami feminista. Revista Nueva Sociedad 286: 93–106. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7319280 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Velasco, Ana María. 2019. La moda en los medios de comunicación: De la prensa femenina tradicional a la política y los/as influencers. Revista Prisma Social 24: 153–85. Available online: https://revistaprismasocial.es/article/view/2845 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Vicente-Fernández, Pilar, Raquel Vinader-Segura, and Sara Gallego-Trijueque. 2019. La comunicación de moda en YouTube: Análisis del género haul en el caso de Dulceida. Prisma Social: Revista de Investigación Social 24: 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wilding, Faith. 2004. ¿Dónde está el feminismo en el ciberfeminismo? Lectora. Revista de Dones i Textualitat 10: 141–51. Available online: https://bit.ly/3j7Wzqg (accessed on 19 April 2022).

| Influencer | Dimension |

|---|---|

| Influencer A | Gender roles and stereotypes |

| Presence of sexist or inclusive language | |

| Social engagement | |

| Influencer B | Gender roles and stereotypes |

| Presence of sexist or inclusive language | |

| Social engagement | |

| Influencer C | Gender roles and stereotypes |

| Presence of sexist or inclusive language | |

| Social engagement | |

| Influencer D | Gender roles and stereotypes |

| Presence of sexist or inclusive language | |

| Social engagement |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arias-Rodriguez, A.; Sánchez-Bello, A. Informal Learning with a Gender Perspective Transmitted by Influencers through Content on YouTube and Instagram in Spain. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080341

Arias-Rodriguez A, Sánchez-Bello A. Informal Learning with a Gender Perspective Transmitted by Influencers through Content on YouTube and Instagram in Spain. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(8):341. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080341

Chicago/Turabian StyleArias-Rodriguez, Alicia, and Ana Sánchez-Bello. 2022. "Informal Learning with a Gender Perspective Transmitted by Influencers through Content on YouTube and Instagram in Spain" Social Sciences 11, no. 8: 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080341

APA StyleArias-Rodriguez, A., & Sánchez-Bello, A. (2022). Informal Learning with a Gender Perspective Transmitted by Influencers through Content on YouTube and Instagram in Spain. Social Sciences, 11(8), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11080341