Abstract

The study of bullying implies analyzing the emotional competences of students, and it has been demonstrated that this phenomenon is due to the poor management of emotions. This study explores whether high scores in Emotional Intelligence (EI) are positively related to academic performance and negatively to bullying. The sample composition focused on students of Compulsory Secondary Education, formed by 3451 subjects aged between 11 and 18 years (50.88% women and 49.12% men). The selection of the high schools was made for non-random convenience, administering Peer Bullying Questionnaire (CAI), TMM-24 and school grades. To analyze the results, a model of structural equations was used by estimating the maximum likelihood together with the bootstrapping procedure. We concluded that EI stands as a protector against bullying and has a positive impact on academic performance. This infers that having greater clarity, repair and emotional attention correlates with a lower possibility of being bullied, at the same time, a school climate without aggressiveness generates positive links towards the school and towards optimal learning environments.

1. Introduction

School violence is a construct with a multidimensional character, which goes beyond a specific fight for a confrontation of interests. Bullying is defined as when a person is harassed repeatedly and over time, experiencing harmful actions by a subject or set of subjects (Smith and Ananiadou 2003).

In recent decades, social concern about violent behavior in the educational field has been increasing (Espelage and Hong 2019; Larrain and Garaigordobil 2020). Bullying produces poor interpersonal relationships, moral transgressions, unjustified aggressiveness, abuse, and mistreatment of one another (Romera et al. 2021) with negative consequences due to the emotional mismatch they experience (Nocentini et al. 2019; Reyzabal and Sanz 2014; Martínez-Martínez et al. 2020). The actions of intimidation and victimization affect physical, psychological, and relational well-being (Menesini and Salmivalli 2017).

The impact of bullying is greater on the victims, although its impact also reaches the aggressors and spectators (Íñiguez Berrozpe et al. 2020; Rusteholz et al. 2021) The sequelae have effects both within the school environment, as well as on physical and mental health and not only while they are living the experience but can last throughout adult life (Rusteholz et al. 2021). As protective factors, having an adequate positive social environment formed by family and friends stands as support in defense against victimization (Lee et al. 2022). The social concern about violent acts between equals in the school environment has to the proliferation of studies at the national and international level on this phenomenon (Feijóo and Rodríguez-Fernández 2021; Hosozawa et al. 2021).

Currently, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) leads projects to ensure quality education for all. To this end, they conducted a large-scale global survey: GSHS- WHO Global School-based Student Health Survey and HBSC-Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study. From the results, the prevalence at a global level stand at one in three students—that is, 32% have been harassed by their peers for one or more days in the last month. Physical harassment is the majority with respect to other typologies, and is more typical of boys, while psychological harassment is more typical of girls.

The prevalence of sexual harassment stands at 11.2%, with the most affected countries being Central America, the Middle East, and North Africa (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2019). The data infers that as children grow, violent experiences decrease. Boys and girls report being bullied in equal measure. The reasons they argue for being victimized are physical appearance, race, and nationality. According to this same study, the prevalence differs depending on the geographical areas. Ordered in decreasing order by region, it is 48.2% in Sub-Saharan Africa, 42.7% in North Africa, 41.1% in the Middle East, 36.8% in Asia-Pacific, 31.7% in North America, 30.3% in Asia, 30.2% in South America, 25% in the Caribbean and Europe, and 22.8% in Central America (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 2019).

The prevalence in Spain is lower than that exhibited in Europe (Amnistía Internacional 2019). However, making a linear comparison is a complex task due to the difference between national and international studies based on theoretical constructs, methodological criteria, and ways of approaching the research, from the collection of data to the analysis of these (Ortega 2001).

Spanish studies at the national level have yielded data on the evolution and development of bullying in schools (Díaz-Aguado Jalon et al. 2013; Usó et al. 2016). Save The Children (2016) showed that 6 out of 10 children have acknowledged being insulted in the last year. Victimization is positioned in 9.3% of respondents. The most prominent type of abuse, according to this study, is a direct and indirect insult as the most recurrent manifestation, followed by rumors, theft of their belongings, threats, beatings, or exclusion.

Other findings (Íñiguez Berrozpe et al. 2020) indicated, through a structural model, that relational bullying is superior to physical bullying and conclude that direct social exclusion is characteristic of the female gender (Martínez Martínez 2020). There are extreme cases in which physical violence predominates over any other typology, which aggravates the situation, by devising suicidal thoughts among adolescents who suffer from it (Aboagye et al. 2022). Other studies point to a new typology, sexting, due to the higher prevalence it is experiencing in the last decade among high school students (Yara Barrense-Dias et al. 2022; Larrain and Garaigordobil 2020).

In relation to academic performance, empirical evidence shows the probability of low academic performance associated with subject failure when school bullying is persistent (Rusteholz et al. 2021). An optimal relationship with teachers affects school performance (Chamizo-Nieto et al. 2021). Behavior and discipline may also be associated with other variables, such as the motivational climate in the classroom (Patel 2018). On the contrary, students with integration problems or maladapted present disruptive behaviors break the rules of coexistence with poor academic performance and low academic expectations (Ansong et al. 2019; Abellán Roselló 2020). Victimization accuses higher rates of school failure in relation to those who have not been involved in the bullying dynamic (Camacho et al. 2013; Botello 2016).

The students assaulted had higher rates of absenteeism because of the manifest fear and perceived insecurity in the school environment with disastrous repercussions on school performance (Hammig and Jozkowski 2013). Increasing student teacher interaction can have great benefits in students with low emotional intelligence (EI), as it has positive effects on their well-being and academic performance (Chamizo-Nieto et al. 2021).

The scientific literature suggests that people have a greater psychological adjustment, which is reflected with higher rates of self-esteem, social support as well as lower rumination and suicidal ideation (Tejada-Gallardo et al. 2020; Li et al. 2021), greater well-being, and satisfaction with life (Salavera et al. 2020), and fewer implications for bullying dynamics (Martínez-Martínez et al. 2020). Other studies show that EI has a moderate relationship with academic performance (MacCann et al. 2020).

Studies carried out on bullying have suggested the need to deepen the emotional dimension for its understanding and evolution in the educational field (Beltran-Catalan et al. 2015), since it is evident that harassment occurs due to poor management of emotions (Villanueva et al. 2014). Addressing problems from violence stands as a previous step to the situations of harassment that occur today in the school environment.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore whether high scores in EI are positively related to academic performance and negatively related to bullying. The hypothesis of this study was that emotional skills have multiple benefits within the classroom, and therefore can be erected as an important value in education.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 3650 students from secondary schools in the province of Almería (Spain) participated. Finally, 3451 students were analyzed after dismissing the loss of information in some questionnaires. 76.2% attended public schools and 23.8% private schools, of which 50.88% were women and 49.12% were men. The age range was between 11 and 18 years (M = 13. 65; DT = 1.36). The selection of the centers was made for non-random convenience.

2.2. Instruments

- -

- Peer Harassment Questionnaire (CAI). It is a tool to assess bullying in relation to victimization in primary and secondary educational contexts (Magaz et al. 2016). This self-report questionnaire consists of 7 scales and various subscales, which evaluate various types of abuse (verbal abuse, direct social exclusion, threats, cyberbullying, indirect social exclusion, object-based aggression, and physical abuse) harassment behaviors according to gender, scenarios in which they take place, coping strategies, characters involved, and post-traumatic stress derived from harassment, experienced by the victim at least in the last 12 months. The reliability evaluated in terms of global internal consistency, using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.91; therefore, it can be considered very high (Cicchetti 1994) offering statistically adequate guarantees for the evaluation of the construct.

- -

- Emotional intelligence (Fernandez-Berrocal et al. 2004). It was implemented through the Spanish-adapted version of TMMS-24 to evaluate “Perceived Emotional Intelligence”. It is a self-report questionnaire that allows EI to be evaluated through 24 items divided into three scales with eight questions asked in each of them. One of the scales refers to the attention that the subject pays to their own feelings, for example “I pay close attention to feelings” another of the scales collects aspects of emotional clarity, “I pay close attention to how I feel”, and finally, a third scale that focuses on emotional repair “I worry about having a good mood”. The items are operationalized on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = nothing and 5 = totally agree. In this study, the reliability evaluated in terms of overall internal consistency, using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.88.

- -

- Academic performance was measured through the results obtained by the students at the end of the academic year and issued by the Seneca Platform. Ratings are concentrated in a range from 0 to 10, with 10 being the highest rating. The grades were extracted from the database of the school application used in the Andalusian educational system.

2.3. Procedure

High schools were contacted to request authorization to conduct the study. The selected sample was collected from 13 high schools according to their availability to participate in the study. Once the centers were ratified, the objectives of the research were explained, and the consent of the legal caregivers was requested through an informative note that they had to present signed, and we exempted those who did not comply with this requirement.

A premise of the study was to save the information anonymously, where good or bad answers were not judged so that answers could be issued with sincerity. The questionnaires were processed with a numerical code. The ethical model embodied by the American Psychological Association and the Helsinki Protocol were respected, and the necessary documentation was obtained from the bioethics commission of University of Almería (UALBIO2017/010).

2.4. Data Analysis

The present study had as its starting point, a descriptive statistical analysis (mean and standard deviation) has been performed. Pearson reconciliations and reliability analyses have been performed, using the statistical program SPSS v.25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The structural equation model (SEM) with AMOS v.19 was used to analyze the predictive relationships of the factors.

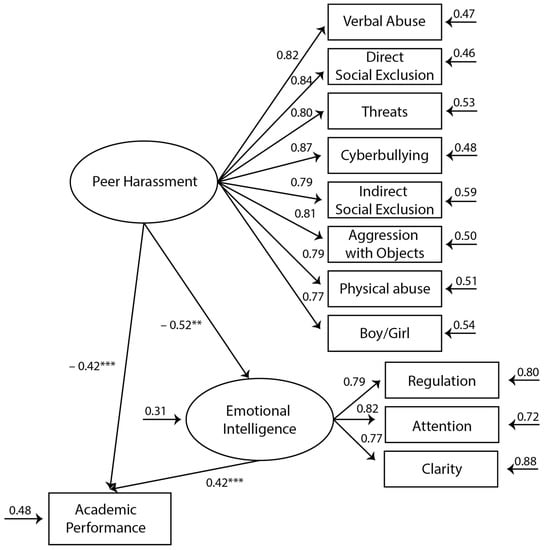

To analyze the hypothetical model (Figure 1), the maximum likelihood estimation method used in conjunction with the start-up procedure was used. Estimators were considered robust as they were unaffected by the lack of normality. To accept or reject the tested models and CFA, several adjustment indices were used: The chi-square coefficient divided by degrees of freedom (2/df), CFI (comparative adjustment index), IFI (incremental adjustment index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis index), RMSEA (mean root quadratic approximation error) plus a 90% confidence interval (CI) and SRMR (standardized mean square residue root). Since 2 is very sensitive to sample size (Hu and Bentler 1999), we used 2/df, considering values below 5 as acceptable (Bentler and Mooijaart 1989). Incremental indices (CFI, TLI, and IFI) show a good fit with values of 0.90 or higher (Schumacker and Lomax 1996) considering error rates (RMSEA and SRMR) equal to or less than 0.06 is acceptable (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993).

3. Results

The mean, standard deviation, reliability analysis through Cronbach’s alpha, and bivariate correlations can be seen in Table 1. The correlations reflected a negative relationship with peer bullying and a positive relationship between emotional intelligence and academic performance. Internal consistency analyses revealed Cronbach’s alpha values greater than 0.70 for each of the variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, reliability analysis, and bivariate correlations.

Analysis of the Model of Structural Equations

Before testing the hypothesis model using an SEM and analyzing the relationships between the variables belonging to the model, a reduction in the number of latent variables was made according to the complexity of the model. Specifically, the latent variables used were peer harassment that included four indicators (verbal abuse, direct social exclusion, threats, cyberbullying, indirect social exclusion, object-based aggression, and physical abuse, in addition to the gender factor. Finally, EI included three indicators (attention to feelings, emotional clarity, and regulation of emotions).

The adjustment indices were adequate: χ2 (52, N = 3451) = 167.10, χ2/gl = 3.21, p < 0.001, IFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.054. (90% CI = 0.043–0.058), SRMR = 0.053. The contribution of each of the factors to the prediction of other variables was examined through standardized regression weights.

The relationships between the different factors that made up the model are described below (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Theoretical model hypothesized through a model of structural equations. All parameters are standardized and statistically significant. Note. *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01.

The results show, on the one hand, that peer bullying negatively predicted EI (β = −0.52, p < 0.01) and academic performance (=−0.42, p < 0.001), and on the other hand, that EI effectively predicted academic success (β = 0.42, p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The results derived from the present research infer that bullying negatively predicts academic performance and EI positively predicts school success. That is, high levels of EI are built as a strong protector against school violence positively influencing academic performance. These findings confirm our starting hypothesis.

Despite the importance of emotions, their role in school has been insignificant (Buitrago and Herrera Torres 2013) hence its low impact on the training curriculum. Enrolling emotions in the school environment would mean the development of these, with an important dynamic component, since it would make it possible to improve interpersonal relationships (Sanchez-Gómez and Bresó Esteve 2018). This would deepen a healthy school coexistence and its impact on the teaching–learning process (Mokobane et al. 2019). Thus, the reason for the integral formation of the student must be included—both the development of cognitive abilities and socio-emotional capacities (Garaigordobil and Peña 2014).

We know that intelligence has traditionally been overvalued by going unnoticed other qualities of the individual when empirical evidence has shown that being intelligent does not guarantee school success (Ibarrola and Zubeldia 2018). Working on emotional competence in the classroom is essential because many problems associated with academic performance are more associated with emotional problems than with lack of capacity (Alzahrani et al. 2019).

Goleman (1996) also determined that school is the ideal place for moral and emotional development by being able to modify inappropriate behavior patterns. The absence of EI can lead to behavioral and/or bullying problems. Current research supports this claim (Bisquerra and López-Gonzalez 2013) while considering it fundamental to improve the academic climate (Barrantes-Elizondo 2016).

There is a direct relationship between bullying and EI, stating that when a subject has deficiencies in EI, they are unable to resolve their negative feelings assertively, using violence (Peña Casares and Aguaded Ramírez 2021). EI is also reduced both in victims of bullying and in adolescents who exhibit antisocial behaviors (Inglés et al. 2014). Otálvaro (2014) inferred that coping strategies in the face of bullying dynamics were identified with emotional competence.

Emotional education is necessary for the daily life of all subjects (Serrat 2017) since this provides sufficient information to promote transformation at the personal and environmental level (Sánchez-Álvarez et al. 2015). From this point of view, emotional skills are necessary both in the educational field and outside the school context (Rodríguez 2017). EI benefits prosocial and helping behaviors, personal well-being and happiness, better social relationships, empathy, and personal and academic self-efficacy (Zhao et al. 2020).

In short, adolescence is a crucial stage for the acquisition of mental and emotional skills, since emotionally intelligent people respond better to the situations posed by life, increasing individual, group, and social well-being (Moshman 2005). Adolescents who have greater affective competencies and regulation of their own emotions do not need to resort to external stimuli, such as alcohol or drugs, to compensate for the negative moods experienced (García del Castillo Rodríguez et al. 2013), and there is a significant and positive relationship between fewer behavioral problems and EI (MacCann et al. 2020).

The findings of other research affirm that having high scores in EI has an impact on higher levels of self-esteem (Martin and Garcia-Garcia 2018), optimal prosocial behaviors (Hosseini et al. 2015), higher rates of emotional regulation and social interaction (Garaigordobil and Peña 2014), better adaptation to the classroom and therefore less impact of disruptive behaviors (Abellán Roselló 2020), increased ability to cope with problems and lower levels of suicidal ideation (Benito et al. 2018), increased control, impulsiveness and aggressive behaviors (Inglés et al. 2014), higher rates of interpersonal sensitivity and empathy (Sánchez-Álvarez et al. 2020), and a better socio-curricular adjustment associated with academic success (Pulido Acosta and Herrera Clavero 2017).

The purpose of the school is to train citizens. The exercise of citizenship requires educational guidelines necessary to regulate optimal coexistence (Bolivar 2016). It is precisely in this citizenship training where EI is essential to work to promote tolerance and respect; therefore, it must be taught in parallel to the school curriculum. These learnings of life and for life must be carried out in the classrooms through the implementation of programs that promote emotional and social growth (Fernandez-Berrocal and Extremera Pacheco 2004). A program of recognized international prestige is the so-called RULER, whose acronym in English responds to recognizing, understanding, labeling, expressing, and regulating emotions (Brackett et al. 2012).

Another example is the CASEL program: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (Dusenbury et al. 2015). The development of both programs has obtained quite promising results in such vital aspects as greater coping with stressors related to the schooling process, while they have generated more prosocial behaviors and lower antisocial behaviors, which has an impact on a better school climate and becomes a strong protector against bullying. Similarly, schools that have developed these programs show a decrease in school dropouts and a higher rate of class attendance, which is an indirect indicator of school success.

At the national level, specifically in Andalusia, the Laboratory of Emotions of the University of Malaga is conducting educational interventions with adolescents, developing strategies and preventive activities to reduce or prevent violence through EI. This is the INTEMO program (Ruiz-Aranda et al. 2013), a program of twelve sessions to be applied during a school year. The proven benefits of this program are related to the teaching of emotional skills, which provide a positive benefit both in the short and long term, reducing socio-educational adaptation problems, improving empathy levels, and reducing impulsive or violent behaviors, which is where bullying nests among school children.

The limitations found in this work are related to self-reported data that, despite being reliable measurement instruments, may present certain biases in terms of social desirability. Another limitation is related to the transversal nature of the design, which prevents establishing a causal relationship between bullying victimization and academic future and emotional impact. Therefore, it is essential to conduct longitudinal research to clarify these facts at different levels of schooling since, when looking for the causes, we must go back to childhood, which is where emotional skills are forged.

On the other hand, gender should be studied since there are differences in socialization and emotional instruction. In this sense, women are more competent when it comes to resolving conflicts and using cooperative resolution strategies, while boys have more aggressive behavior (Garaigordobil Landazabal et al. 2016). Future lines of research should be developed by promoting multidisciplinary teams not only from the educational community but also from the family, centers, and associations to minimize or alleviate the problems that underlie bullying.

From this point of view, it is advisable to generate training plans for management teams, professionals, and parents, creating spaces for collaboration, reflection, and analysis that improve coexistence, while addressing the impact of bullying to provide an effective and early response to this phenomenon (Martínez Martínez 2020). The results of a recent systematic review revealed the importance of designing and implementing programs of EI in the school context as prevention and action against bullying (Rueda et al. 2021).

5. Conclusions

The present work was able to verify that having low levels of EI predicted a greater probability of victimization by bullying as well as greater negative results in school performance. That is, EI is a protector against bullying and has a positive impact on school success. It was shown that the ability to recognize feelings and manage them properly is essential to establishing positive relationships, as it improves the school climate and involvement in schoolwork and avoids problems arising from violence.

The research presented contributes to the study of the victimization of harassment and provides updated data contributing to its understanding. Furthermore, this study verified the emotional impact experienced by high school students who have been bullied. There is evidence of the need to promote and evaluate programs that promote confrontational strategies to alleviate the consequences that originate in the short and long term.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.M.-M.; Data curation, A.M.M.-M.; Formal analysis, J.M.A.-P. and R.L.-L.; Funding acquisition, C.R.; Investigation, A.M.M.-M.; Methodology, A.M.M.-M. and A.M.-L.; Resources, C.R.; Software, J.M.R.-F.; Supervision, J.M.A.-P. and R.L.-L.; Validation, A.M.-L.; Writing—original draft, A.M.M.-M.; Writing—review and editing, A.M.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Bioethics Commission of the University of Almería (Reference: UALBIO 2017/010).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abellán Roselló, Laura. 2020. Relación entre inteligencia emocional y disminución de conductas disruptivas en educación primaria. Praxis Investigativa ReDIE: Revista electrónica de la Red Durango de Investigadores Educativos 12: 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Aboagye, Richard G., Dickson O. Mireku, John J. Nsiah, Bright O. Ahinkorah, James B. Frimpong, John E. Hagan, Jr., Eric Abodey, and Abdul A. Seidu. 2022. Prevalence and psychosocial factors associated with serious injuries among in-school adolescents in eight sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Public Health 22: 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, Mona, Manal Alharbi, and Amani Alodwani. 2019. The Effect of Social-Emotional Competence on Children Academic Achievement and Behavioral Development. International Education Studies 12: 141–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnistía Internacional. 2019. Hacer la Vista Gorda: El acoso Escolar en España, un Asunto de Derechos Humanos. Madrid: Amnistía Internacional. Available online: https://doc.es.amnesty.org/ms-opac/recordmedia/1@000031105/object/40724/raw (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Ansong, David, Gina Chowa, Rainier Masa, Mathieu Despard, Michael Sherraden, Shiyou Wu, and Isaac Osei-Akoto. 2019. Effects of Youth Savings Accounts on School Attendance and Academic Performance: Evidence from a Youth Savings Experiment. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 40: 269–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrantes-Elizondo, Lena. 2016. Educación emocional: El elemento perdido de la justicia social. Revista Electrónica Educare 20: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrense-Dias, Yara, Lorraine Chok, Sophie Stadelmann, André Berchtold, and Joan-Carles Suris. 2022. Sending One’s Own Intimate Image: Sexting Among Middle-School Teens. Journal of School Health 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran-Catalan, Maria, Izabela Zych, and Rosario Ortega-Ruiz. 2015. El papel de las emociones y el percibido en el proceso de superación de los efectos del acoso escolar: Un estudio retrospectivo. Ansiedad y Estres 21: 219–32. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, Oscar Javier Mamani, Magaly Brousett Minaya, Duumy Neyma Ccori Zúñiga, and Karen Shirley Villasante Idme. 2018. La inteligencia emocional como factor protector en adolescentes con ideación suicida. Duazary: Revista Internacional de Ciencias de la Salud 15: 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, Peter M., and A. B. Mooijaart. 1989. Choice of structural model via parsimony: A rationale based on precision. Psychological Bulletin 106: 315–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, Rafel, and Luis López-Gonzalez. 2013. Validación y análisis de una escala breve para evaluar el clima de clase en educación secundaria. Instituto Superior de Estudios Psicológicos. ISEP Science 5: 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bolivar, Antonio. 2016. Educar democráticamente para una ciudadanía activa. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social (RIEJS) 5: 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botello, Héctor A. 2016. Efecto del acoso escolar en el Desempeño Lector en Colombia. Zona Próxima 4: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brackett, Marc A., Susan E. Rivers, Maria R. Reyes, and Peter Salovey. 2012. Enhancing academic performance and social and emotional competence with the RULER Feeling Words Curriculum. Learning and Individual Differences 22: 218–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, Rafael, and Lucía Herrera Torres. 2013. Matricular las emociones en la escuela, una necesidad educativa y social. Praxis & Saber. Revista de Investigación y Pedagogía 4: 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, Castro, Pamela Conde, Carolin Jara, Robert Polo, and Sharon Ríos. 2013. Bullying and school academic performance in the 2nd year of Secondaty of the I.E “San Luis de la Paz” of the district of Nuevo Chimbote. Research Journal of Psychology Students, Jang 2: 147–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chamizo-Nieto, María Teresa, Christiane Arrivillaga, Lourdes Rey, and Natalio Extremera. 2021. The Role of Emotional Intelligence, the Teacher-Student Relationship, and Flourishing on Academic Performance in Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Study. Frontiers in Psychology 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, Domenic V. 1994. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment 6: 284–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Aguado Jalon, María José, Rosario Martinez Arias, and Javier Martín Babarro. 2013. Bullying among adolescents in Spain. Prevalence, participants’ roles and characteristics attributable to victimization by victims and aggressors. Revista de Educación (Madrid) 362: 348–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusenbury, Linda, Sophia Calin, Celene E. Domitrovich, and Roger P. Weissberg. 2015. What Does Evidence-Based Instruction in Social and Emotional Learning Actually Look Like in Practice? A Brief on Findings from CASEL’s Program Reviews. CASEL District Resource Center. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED574862.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Espelage, Dorothy L., and Jun Sung Hong. 2019. School climate, bullying, and school violence. In School Safety and Violence Prevention: Science, Practice, Policy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 45–69. [Google Scholar]

- Feijóo, Sandra, and Raquel Rodríguez-Fernández. 2021. A Meta-Analytical Review of Gender-Based School Bullying in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, Pablo, and Natalio Extremera Pacheco. 2004. El papel de la inteligencia emocional en el alumnado: Evidencias empíricas. REDIE. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa 6. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=15506205 (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Fernandez-Berrocal, Pablo, Natalio Extremera, and Natalia Ramos. 2004. Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Modified Version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychological Reports 94: 751–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, Maite, and Ainize Peña. 2014. Intervención en las habilidades sociales: Efectos en la inteligencia emocional y la conducta social. Psicología Conductual 22: 551–67. [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil Landazabal, Maite, Juan Manuel Machimbarrena Garagorri, and Carmen Maganto Mateo. 2016. Adaptación española de un instrumento para evaluar la resolución de conflictos (Conflictalk): Datos psicométricos de fiabilidad y validez. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes 3: 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- García del Castillo Rodríguez, José Antonio, Alvaro García del Castillo López, Mónica Gázquez Pertusa, and Juan Carlos Marzo Campos. 2013. La Inteligencia Emocional como estrategia de prevención de las adicciones. Health and Addictions: Salud y Drogas 13: 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goleman, Daniel. 1996. Inteligencia Emocional. Barcelona: Editorial Kairós. [Google Scholar]

- Hammig, Bart, and Kristen Jozkowski. 2013. Academic Achievement, Violent Victimization, and Bullying Among U.S. High School Students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 28: 1424–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosozawa, Mariko, David Bann, Elian Fink, Esme Elsden, Sachiko Baba, Hiroyasu Iso, and Praveetha Patalay. 2021. Bullying victimisation in adolescence: Prevalence and inequalities by gender, socioeconomic status and academic performance across 71 countries. eClinicalMedicine 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, Seyed Mahdi, Asad Allah Zangouei, Masoud Ramroodi, and Mohammad Akbaribooreng. 2015. Relating emotional intelligence and social competence to academic performance in high school students. International Journal of Educational and Psychological Researches 1: 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarrola, Begoña, and Txaro Etxeberria Zubeldia. 2018. Inteligencias Múltiples: De la teoría a la Práctica Escolar Inclusiva. Madrid: Ediciones SM España, vol. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Inglés, Cándido J., María S. Torregrosa, José M. García-Fernández, María C. Martínez-Monteagudo, Estefanía Estévez, and Beatriz Delgado. 2014. Conducta agresiva e inteligencia emocional en la adolescencia [Aggressive behavior and emotional intelligence in adolescence]. European Journal of Education and Psychology 7: 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Íñiguez Berrozpe, Tatiana, Jacobo Cano de Escoriaza, María del Pilar Alejandra Cortés Pascual, and Carmen Elboj Saso. 2020. Modelo estructural de concurrencia entre ‘bullying’ y ‘cyberbullying’: Víctimas, agresores y espectadores. REIS: Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 171: 63–84. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7518517.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Jöreskog, Karl G., and Dag Sörbom. 1993. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chicago: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Larrain, Enara, and Maite Garaigordobil. 2020. Bullying in the Basque Country: Prevalence and differences depending on sex and sexual orientation. Clínica y Salud 31: 147–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jungup, Beop-Rae Roh, and Kyung-Eun Yang. 2022. Exploring the association between social support and patterns of bullying victimization among school-aged adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review 136: 106418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Qian, Lan Guo, Sheng Zhang, Wanxin Wang, Wenyan Li, Xiaoliang Chen, Jingman Shi, Ciyong Lu, and Roger S. McIntyre. 2021. The relationship between childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students: The multiple mediating effects of emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of Affective Disorders 288: 129–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, Carolyn, Yixin Jiang, Luke E. R. Brown, Kit S. Double, Micaela Bucich, and Amirali Minbashian. 2020. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 146: 150–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaz, Ana M., Paloma Chorot, Miguel A. Santed, Rosa M. Valiente, and Bonifacio Sandín. 2016. Evaluación del bullying como victimización: Estructura, fiabilidad y validez del Cuestionario de Acoso entre Iguales (CAI). Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica 21: 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Deborah, and Mercedes Garcia-Garcia. 2018. Education Model transformation in regards to learning an competence development. A Case study. Bordon-Revista De Pedagogia 70: 103–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Martínez, Ana María. 2020. Influencia del Acoso y Ciberacoso Escolar en el Rendimiento Académico y la Inteligencia Emocional Percibida en Estudiantes de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. Almería: Universidad de Almería. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Martínez, Ana María, Remedios López-Liria, José Manuel Aguilar-Parra, Rubén Trigueros, María José Morales-Gázquez, and Patricia Rocamora-Pérez. 2020. Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Cybervictimization, and Academic Performance in Secondary School Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menesini, Ersilia, and Christina Salmivalli. 2017. Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychology, Health & Medicine 22: 240–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokobane, Maria, Basil J. Pillay, and Anneke Meyer. 2019. Fine motor deficits and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in primary school children. South African Journal of Psychiatry 25: 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshman, David. 2005. Adolescent Psychological Development: Rationality, Morality, and Identity. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nocentini, Annalaura, Giada Fiorentini, Ludovica Di Paola, and Ersilia Menesini. 2019. Parents, family characteristics and bullying behavior: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 45: 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Ricoeur. 2001. Narración y comprensión del otro. In El prendmiento Narrativo. Construcción de Historias y Desarrollo del Conocimiento Social. Edited by A. Smorti. Sevilla: Editorial Mergablum. [Google Scholar]

- Otálvaro, Juliana Montoya. 2014. Inteligencia emocional como estrategia de afrontamiento frente el Bullying. Revista Entornos 27: 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Patel, Nilesh. 2018. Effect of Integrated Feedback on Classroom Climate of Secondary School Teachers. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE) 7: 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña Casares, M. J., and E. Aguaded Ramírez. 2021. Inteligencia emocional, bienestar y acoso escolar en estudiantes de educación primaria y secundaria. Journal of Sport and Health Research 13. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/extart?codigo=8060937 (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Pulido Acosta, Federico, and Francisco Herrera Clavero. 2017. La influencia de las emociones sobre el rendimiento académico. Ciencias Psicológicas 11: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyzabal, Maria V., and Ana Isabel Sanz. 2014. Resilience and Bullying. The Strength of Education. Madrid: Editorial Muralla. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Francisco Manuel Morales. 2017. Relaciones entre afrontamiento del estrés cotidiano, autoconcepto, habilidades sociales e inteligencia emocional. European Journal of Education and Psychology 10: 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, Eva M., Rosario Ortega-Ruiz, Kevin Runions, and Antonio Camacho. 2021. Bullying Perpetration, Moral Disengagement and Need for Popularity: Examining Reciprocal Associations in Adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 50: 2021–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, Pilar, Nuria Pérez-Romero, María Cerezo, and Pablo Fernández-Berrocal. 2021. The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Adolescent Bullying: A Systematic Review. Psicología Educativa 28: 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Aranda, D., R. Cabello, J. M. Salguero, R. Palomera, N. Extremera, and P. Fernández-Berrocal. 2013. Programa INTEMO. Guía para Mejorar la Inteligencia Emocional de los Adolescentes. Madrid: Pirámide. [Google Scholar]

- Rusteholz, Gisela, Mauro Mediavilla, and Luis Pires. 2021. Impact of Bullying on Academic Performance: A Case Study for the Community of Madrid. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavera, Carlos, Pablo Usán, Pilar Teruel, and José L. Antoñanzas. 2020. Eudaimonic Well-Being in Adolescents: The Role of Trait Emotional Intelligence and Personality. Sustainability 12: 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Álvarez, Nicolás, Natalio Extremera, and Pablo Fernandez-Berrocal. 2015. Maintaining life satisfaction in adolescence: Affective mediators of the influence of perceived emotional intelligence on overall life satisfaction judgments in a two-year longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Álvarez, Nicolás, María Pilar Berrios Martos, and Natalio Extremera. 2020. A meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and academic performance in secondary education: A multi-stream comparison. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Gómez, Martin, and Edgar Bresó Esteve. 2018. Inteligencia emocional para frenar el rechazo en las aulas. Agora de Salut 5: 275–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Save The Children. 2016. Necesita Mejorar. Por un Sistema Educativo que no Deje a Nadie Atrás. Madrid: Save the Children. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker, Randall E., and Richard G. Lomax. 1996. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. In A beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Serrat, Olivier. 2017. Understanding and Developing Emotional Intelligence. In Knowledge Solutions: Tools, Methods, and Approaches to Drive Organizational Performance. Edited by Olivier Serrat. Singapore: Springer, pp. 329–39. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Peter K., and Katerina Ananiadou. 2003. The Nature of School Bullying and the Effectiveness of School-Based Interventions. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies 5: 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada-Gallardo, Claudia, Ana Blasco-Belled, Cristina Torrelles-Nadal, and Carles Alsinet. 2020. How does emotional intelligence predict happiness, optimism, and pessimism in adolescence? Investigating the relationship from the bifactor model. Current Psychology 39: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2019. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483 (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Usó, Inmaculada, Lidón Villanueva, and Juan E Adrián. 2016. Impact of peer mediation programmes to prevent bullying behaviours in secondary schools/El impacto de los programas de mediación entre iguales para prevenir conductas de acoso escolar en los centros de secundaria. Infancia y Aprendizaje 39: 499–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, Lidón, Vicente Prado-Gascó, Remedios González-Barrón, and Inmaculada Montoya. 2014. Conciencia emocional, estados de ánimo e indicadores de ajuste individual y social en niños de 8–12 años. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology 30: 772–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Jia-Lin, Dan Cai, Cai-Yun Yang, John Shields, Zhe-Ning Xu, and Chun-Ying Wang. 2020. Trait emotional intelligence and young adolescents’ positive and negative affect: The mediating roles of personal resilience, social support, and prosocial behavior. Child & Youth Care Forum 49: 431–48. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).