1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated an unprecedented number of challenges resulting in significant local and global scale disruptions in social, economic, environmental, and political systems that are likely to persist for some time (

Helm 2020;

International Monetary Fund 2020). Virtually all nations throughout the world have attempted to mitigate the impact of the virus by reducing the chance of transmission that can occur through contact spread. Various public health measures have been implemented to achieve this, including the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) such as face masks; social distancing and the restriction of large public gatherings; the establishment of testing, isolation, and quarantine protocols; and, in some extreme cases, community containment, curfew orders, and lockdowns (

Gautam and Hens 2020).

Mainstream media has played a critical role in the dissemination of information related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Numerous studies have shown that media coverage during the pandemic has likely influenced the perceptions and attitudes of the public toward a wide range of issues, including food consumption, social distancing protocols, vaccines, travel plans, and other socio-economic activities (

Chemli et al. 2020;

Gozzi et al. 2020;

Helm 2020). However, it has also been demonstrated that the information disseminated by media outlets does not always result in the greater good for society and may even exacerbate perverse situations related to the pandemic, such as questioning the value of adhering to social distancing and other recommended public health guidelines, thereby promoting the spread of the virus and potentially increasing the number of fatalities that have occurred (

Ponizovskiy et al. 2020).

Additionally, media coverage during the pandemic was shown to have been plagued by a diverse assortment of biases, i.e., gatekeeper, coverage, and statement biases (

AlAfnan 2020). Media reporting afflicted by biased narrative accounts of any kind may potentially obscure the true nature of realities that exist for groups in which a negative proclivity has been formed against. Bias in media representations can therefore have severe and long-lasting ramifications on the reputations of marginalized social groups, exacerbating or at least perpetuating many of the characteristically disdainful and detrimental stereotypes commonly expressed toward them by the wider public, further cementing their subordinate or stigmatized status.

During the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, Jamaica’s major media outlets regularly ran television news stories that were simultaneously posted online which showcased breaches of government mandated public health protocols and social distancing guidelines by impoverished inner-city populations, informal sector workers, and street traders. Breaches committed by persons belonging to these groups therefore dominated the national news cycle at the time. Consequently, a high volume of public commentary was generated with hundreds of online comments found for each video news story.

Using a qualitative approach, this paper aims to explore the media representations of the public response to health protocols implemented during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Jamaica. A content analysis of the video news stories will be used to analyze the nature of the public discourse toward the vulnerable groups that were featured. A thematic discourse analysis will be used to catalog the public attitudes and sentiments that were formed in response, which were found in the hundreds of online user comments that were generated for each news story. In doing so, the study will attempt to explain the implications of biased media representations that engendered a prejudiced public discourse toward different impoverished groups in Kingston while also examining how these representations potentially reproduced existing expressions of ‘othering’, social divergence, and social polarization.

2. Theoretical Framework

Marginalized populations have traditionally been disproportionately affected by periods of both man-made and natural crises, with the COVID-19 pandemic being no exception (

Daly et al. 2020). Furthermore, periods of crises at the local, national, or global scale are said to unearth various inequalities that would have otherwise remained hidden in normal day-to-day activities (

Kantamneni 2020). The restrictions in the availability of socio-economic and, perhaps more than ever, technological resources have thus exacerbated the vulnerabilities and subsequent risks posed to marginalized groups, thereby unearthing multiple forms of inequality (

Daly et al. 2020). The perverse socio-economic and technological conditions that characterize the economically marginalized tend to co-exist in a ‘vicious digital cycle’ where the two interact, intensify, and are said to produce new forms of exclusion (

Warren 2007).

The lack of access to technologies is thus a predominant driver of inequity in the transition to a modern digital era, which has only been fast tracked by the current pandemic. If not readily accessible, it can greatly inhibit one’s ability to effectively participate in the new digital economy that is becoming more and more integral for increasing social inclusion and reducing poverty (

Gurstein 2003;

Warren 2007). For example, the pandemic has seen a number of public and information dissemination pipelines shift toward a digital mode of operation. The provision of basic social services and welfare systems has also been digitalized across many jurisdictions, with the inability to access these posing a significant challenge for economically marginalized populations who tend to be among those most negatively impacted by the digital divide and inadequate ICT access (

Mahabir and Anderson 2020). Traditionally, the economically marginalized are likely to rely more heavily on person-to-person interactions for employment and social opportunities compared to other income groups, making it especially difficult for them to effectively transition to utilizing and accessing digital technologies, platforms, and work(places) during the pandemic (

Bargain and Aminjonov 2020;

Delaporte and Pena 2020).

The disproportionate level of negative public focus on marginalized groups in media discourses and coverage during the pandemic has been demonstrated to be a common occurrence throughout many countries (

Daly et al. 2020). It should be noted that while this is a critical social issue with significant ramifications for the marginalized groups being featured, there has been relatively little scholarly work exploring this issue through the lens of COVID-19. However, the propensity of highlighting the actions of the marginalized as opposed to other population segments may still be explained by the existing literature regarding the link among discrimination, public discourses, and public attitudes.

Wacquant et al. (

2014) argues that the concept of a ‘spatial taint’ can be brought about when disparaging images are used to represent a certain group or place. This may lead to the territorial stigmatization of said group or place, which ultimately results in social disintegration. This is relevant to the narrative being presented as media portrayals highlighting breaches of social distancing protocols have led to aggressive reactions and negative discourses being formed against various groups (

De Neys et al. 2020). The inability of marginalized populations to effectively adhere to social distancing protocols, combined with them being a primary focal point for media outlets during the pandemic, would have significantly increased their risk of territorial stigmatization. Additionally, the public may have been quick to blame marginalized communities for endangering the well-being of the general population due to their breaches being pinned on an intrinsic lack of moral character, rather than the variety of capability constraints they face (

De Neys et al. 2020).

The concept of othering is also considered to be a central process in the development of stigmatized identities among affected populations (

Joffe 2011), with the stigmatization attributed to these groups shown to result from a range of societal and social influences relating to government policies, media outlets, culture, and socialization (

Zierler et al. 2000). The concept of othering has long been associated with global pandemics and occurs among several divisional lines in society, such as gender, social class, orientation, race, culture, and nationality (

Dionne and Turkmen 2020;

Smith 2000;

Petros et al. 2006). While othering may be considered part and parcel of everyday life, it has been demonstrated to be extremely prevalent during periods of crisis due to increasing levels of anxiety among the general populace (

Joffe 2007). This results in marginalized groups being considered a threat and ascribed blame for any given social issue (

Joffe 2011). Division is also inherently associated with othering as the dichotomous notion of a majority righteous ‘us’ and a minority disruptive ‘them’ is formed. The marginalized, already considered transgressive or menacing outsiders in terms of ethno-national, socio-economic, or socio-cultural norms, are therefore most likely to be branded under the label ‘them’ during crises.

The onset of COVID-19 has unearthed many latent social issues that are intricately linked with the process of othering. Globally, blame for the virus’s spread has commonly been attributed to marginalized populations as both leaders and citizens alike try to find scapegoats for its continued transmission (

Dionne and Turkmen 2020). Fueled by government rhetoric during the early stages of the pandemic which classified COVID-19 as the ‘China Virus’ and ‘Kung Flu’, Asians and Asian-Americans have been challenged with an uptick in incidents of discrimination in the United States (

Yang et al. 2020). Asian populations were frequently victims of racially motivated assaults and violent attacks, with negative discourses being formed against them “faster than the spread of the pandemic itself” (

Yan et al. 2020).

In Singapore, the country’s ethnic Chinese majority expressed resentment over the spread of COVID-19 toward its migrant worker population who, ironically, tended to be Asian themselves. Arriving primarily from Bangladesh, India, and mainland China, workers were forced to reside in overcrowded dormitories, often with twenty or more persons sharing a single room (

Fordyce 2020). Such tightly packed living quarters made social distancing difficult and was associated with an eventual second outbreak (

Leung 2020). However, local politicians and the public tended to disregard these pertinent factors, instead choosing to blame the virus’s spread on the mere existence of migrants in the city-state. Xenophobia surrounding COVID-19 was not just limited to persons from Asia, as was shown to be the case in mainland China where African migrants were ostracized. This culminated in the refusal of service and evictions of ‘black people’ in early 2020, which resulted in many African nationals sleeping on the streets (

Sun 2020).

The discrimination and blame faced by marginalized groups during the pandemic have therefore induced an array of effects that have negatively impacted many facets of their lived experience, including their safety, security, mobility, and psychological health.

Yang et al. (

2020) suggest that Asians and Asian-Americans expressed greater feelings of fear of being discriminated against during the pandemic, which was consequently associated with lower levels of subjective well-being. Outside of personal impacts, policy can also be implemented against already vulnerable populations, which not only hinders the efficacy of future response programs, but may also encourage further stigmatization and discrimination against them (

Dionne and Turkmen 2020). For example, many countries decided to implement travel bans or quarantine procedures that solely targeted mainland Chinese nationals.

Dionne and Turkmen (

2020) highlighted that this decision was not based on epidemiological data and often exempted the quarantine process from other races or nationalities that also had the potential to spread the virus.

3. Materials and Methods

A qualitative approach was used for data gathering and analysis. Different techniques were used to address the core objectives of the research, which revolved around separate units of analysis. To explore the expressions of ‘othering’ and social divergence, comments on YouTube videos posted by the country’s largest local broadcasting network, Television Jamaica Ltd. (TVJ), were used as proxies for general societal sentiments. While the findings can hardly be considered as quantitatively representative, they appropriately capture the texture of the discourse commonly expressed by the national populace.

3.1. Selection Criteria for Videos Included in Analysis

TVJ was selected based on its comparatively significant reach, which was reflected by its high visibility and viewership for both television and online media. Relative to the second largest broadcasting network, they occupy a great deal of the market share and have a more visible online presence. TVJ occupies approximately 78% of the viewer market share (

Market Research Services Limited 2019), with approximately 272,000 subscribers to their YouTube channel, which was six times the number of subscribers of their main competitor’s channel at the time the data collection took place. Nearly all the content produced by the television station is posted to their YouTube channel and, unlike other national television stations, there was extensive coverage related to the reactions of the public to the COVID-19 crisis. These videos also generated substantially higher levels of viewership, with many securing more than 20,000 views within the first day of posting compared to less than 1000 views for their closest competitor. Accordingly, the online presence and relatively high volume of public discourse in the form of comments was used as the main filter for selecting videos that instigated significant and varied public reactions.

A second level of selection was based on the date and content of videos posted on TVJ’s YouTube channel. For this aspect of selection, a reference period of approximately one month, from 10 March to 14 April 2020, was used. The day of 10 March 2020 marks the date of the first reported COVID-19 case in Jamaica and represents a specific point in time when calls for social distancing were significantly intensified by the Government of Jamaica. Anecdotal observations indicate that public awareness campaigns promoted through various media sources were geared toward enhancing national efforts in offsetting the transmission of the virus. As part of this campaign to improve public awareness, some media houses produced content that cataloged local reactions to calls for social distancing. In many instances, this content seemed to focus on the experiences of people from low-income neighborhoods across the city—both their home-life and their activity as traders and consumers in Kingston’s central business district. All videos containing such material that were posted during the stipulated period were selected, adding up to six videos in total, and their comments were extracted using a simple API (Application Programming Interface) script software called ‘YouTube Comment Downloader’ (

Bouman 2021).

3.2. Thematic Discourse Analysis of Video Comments

The comments were extracted from the six videos posted during the reference period. The number of comments ranged from around seven to well over five hundred for any given video, with a total of 790 comments being analyzed. The public discourse expressed in the user comments under each video was manually coded and assigned themes using an iterative, collaborative process among a team of trained qualitative researchers. The choice to code comments manually was based on several factors. The use of computer-assisted coding (CAC) software has often been shown to be prone to interpretation errors when attempting to identify patterns and themes during textual analysis (

Krippendorff 2018). These concerns were compounded by the fact that much of the comments were not in standard English, but in the English Creole language of Jamaican Patois that is spoken throughout the island-nation and by its diasporic populations (

Kraidy 2006). There was little confidence among researchers that coding software would be able to adequately recognize and distinguish the unique facets of the syntax and semantics of Jamaican Patois. In the case of this study, human interpretation by an experienced team of qualitative researchers was therefore deemed most suitable given the volume and dominant language of the comments, potentially offering a higher level of accuracy and quality of coding outcomes when compared to computer-assisted methods.

The manual coding process was undertaken as a collaborative effort between two researchers who read and coded the comments, shared ideas, and worked alongside each other to develop appropriate codes. Each comment was coded under different emergent themes based on the nature of the sentiment expressed toward the actions of the marginalized populations depicted in the videos. These thematic classifications were determined by considerations such as the wording of the comment; the implied seriousness or tone of the comment; the wider context within which the actions were discussed; and the positioning of the discussion of said actions. It was possible for a comment to be coded under multiple themes or be deemed irrelevant if not referencing or discussing the actions of the persons being depicted, or by not providing an evaluative opinion or statement. Based on its assigned thematic classification, each comment was also more broadly defined as denoting positive, negative, mixed, and neutral (irrelevant) sentiments.

As part of the coding process, the content of each comment was recorded in a database, resulting in the production of a codebook. After reviewing the comments multiple times and sharing the outcomes with a senior-level researcher for peer debriefing, it was common for comments to be assigned alternate thematic codes as different perspectives or interpretations may have emerged. After this process, some themes were combined while others were removed completely as the codebook of themes came to be refined and eventually finalized. This synthesis comprised the primary material for a thematic analysis centered on the extent to which public sentiments reflected social divergence and the entrenchment of the social divide in Jamaica.

4. Results

4.1. Description of Video Content

The videos generally depicted a range of experiences and reactions to social distancing guidelines and other regulations imposed by the state. In one video titled, ‘Social distancing appeal ignored’, the scenes depicted look no different from a typical day in the country’s largest business district, downtown Kingston. This area houses a significant portion of Jamaica’s informal economy and is the operating space for many street traders. Dense crowds are common as customers, many of whom originate from the lower socio-economic strata of society, are magnetized by comparatively low prices and a high diversity of products and services. However, with narrow pathways and high pedestrian traffic, practicing social distancing is exceptionally difficult. Additionally, in the absence of significant financial support from the state, the desire to meet basic needs has compelled many street traders to continue operations amidst the discouragement imbued in state and public rhetoric. Interviews from the various news reports generally suggested that their lack of compliance was largely due to dire economic need linked to precarious financial conditions. As one trader in the video articulates: “It’s who has money that keeps their distance but we as poor people can’t keep our distance. We have to mix and mingle in the crowd to look [after] our own… it’s people who are rich who keep their distance”.

In much of the discourse presented in the video, hunger was frequently positioned by the marginalized to be more ominous than the consequences of contracting COVID-19. Such comparative evaluations of risk are likely to underlie actions that have been the source of the discord evident in the comments on the video. Other videos revolved around the responses of residents in low-income neighborhoods to the restrictions on movement imposed by the state. On 1 April 2020, the government announced a national curfew restricting movement of residents between the hours of 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. A week later, these restrictions were tightened and residents were required to remain indoors between 3 p.m. and 7 a.m. One video, which generated approximately 80,000 views and 225 comments at the time of the analysis, depicted residents gathering on neighborhood streets during curfew hours. The residents used boredom and hunger to justify their desire to remain outdoors. Additionally, some residents suggested that the curfew restrictions did not align with the cultural practices of remaining on the street late at night, a common occurrence in many low-income neighborhoods in Kingston where large extended families are often crammed into a small living space. These expressions of resistance were commonplace in sections of West Kingston and other low-income areas.

4.2. Description of Video Comments

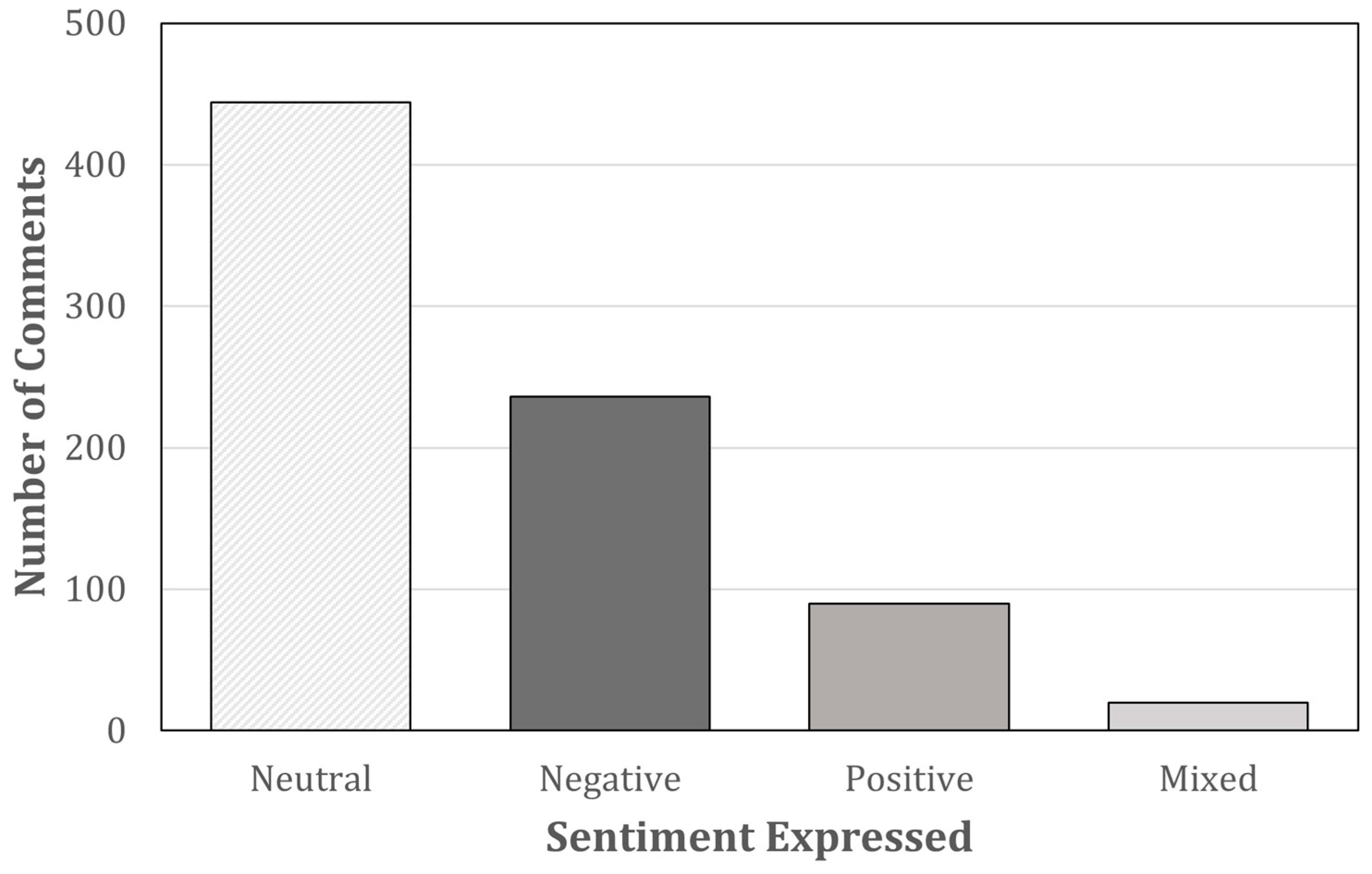

The online comments for local news segments were a richly encoded discourse characterized by a range of opinions and sentimental attitudes that were classified by researchers as positive, negative, mixed, or neutral (irrelevant). Negative sentiments often embodied expressions of stark disapproval of the actions of marginalized groups depicted in videos, either ignoring or showing blatant insensitivity to their debilitating social and economic circumstances. Such comments also evoked a slew of negative feelings and emotions including anger, anxiety, contempt, disdain, fear, frustration, and nervousness. Positive sentiments were typically associated with responses that showed some form of sympathy, understanding, or support for the actions depicted in the videos, thereby representing a type of counter-narrative discourse. There were also a small number of comments that contained an eclectic mix of sentiments and were classified as such (

Figure 1).

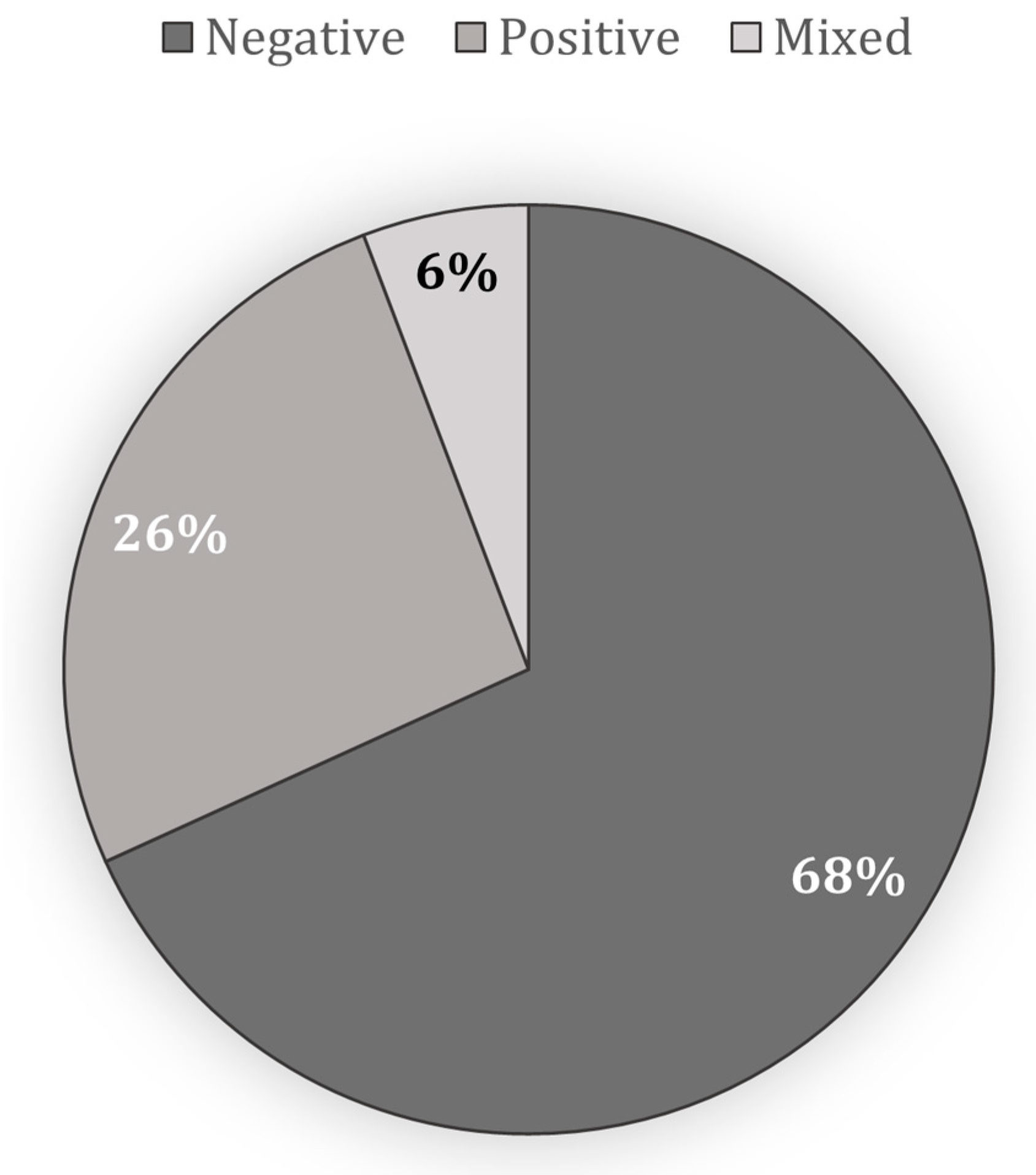

It is important to note that most of the comments made in response to the selected videos were deemed neutral or irrelevant, having not made any reference to the subject matter being depicted. For the comments that did substantively engage with the content of the videos, several themes emerged. The themes were classified into the two broad categories of discourses that seemed to have dominated the commentary, each evoking a different sentimental attitude: social divergence (negative) and social diversity (positive). Ignoring the neutral comments, the negative sentiments, positive sentiments, and mixed sentiments accounted for 68%, 26%, and 6% of all comments, respectively (

Figure 2) (

Table 1).

4.3. Discourses of Social Divergence

4.3.1. Place-Based Discrimination

Based on the content of the videos, it was clear that there was an obvious geographic bias, as it relates to the coverage of compliance and reactions to restrictions. Attention was wholly centered on markets and living spaces in the most depressed communities in Kingston, which are dominated by high levels of poverty, crime, and violence. This inordinate focus placed on capturing the experiences of low-income, economically vulnerable persons, while seemingly ignoring the violations of social distancing guidelines in other areas of the city frequented by persons of varying socio-economic backgrounds (i.e., middle- and upper-class areas and shopping centers), points to the content of these video news stories engendering an inherently biased and unbalanced perspective.

Although there were some online users who expressed concern about the apparent bias of the news stories, much of the resultant public discourse generated from user comments ultimately evoked similar lines of prejudicial thinking. It can therefore be said that both the media coverage and the comments produced from it mostly failed to acknowledge several extenuating socio-economic realities that tend to characterize Kingston’s population of impoverished city-dwellers who were prominently featured. Due to their comparatively higher rates of chronic resource-deprivation, cramped and overcrowded living conditions, reliance on face-to-face informal sector work, and a lack of savings and financial assets, it has been a struggle for many marginalized Kingstonians to cope with the slew of disruptions brought on by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and fully adhere to the protocols prescribed under the ‘new normal’.

To be clear, these various debilitating factors should not be seen as excuses or moral justifications for the actions of non-compliant individuals; rather, they represent underlying socio-economic conditions that have very real implications on people’s ability to fully adhere to public health guidelines. Ideally, they should at least be recognized for the role they might play in preventing those affected from adhering to COVID-19 protocols and should be addressed to improve public health outcomes. However, these considerations were ignored entirely by most commenters who were found to have expressed overtly prejudiced rhetoric that unjustly scrutinized the poor urban communities being featured: “I am disappointed with the JCF [local police]. You should have lock[ed] up who you catch [breaking protocols]. And that’s not Tivoli Gardens, that’s dirty Lizard Town [colloquial slur for community]”.

Many commenters cast blame on the lack of compliance among the marginalized purely on the basis of their place identity. A person’s inability to conform to COVID-19 health protocols and their place of residence was often suggested to be strongly conflated. Many commenters made blatant claims that residence in a ghetto or garrison community in Kingston equated to being uninformed, unruly, and disobedient. This can be observed in such statements as, “Can’t help ignorant people…these people proud to show how unruly the garrison is!” and “Ignorance, indiscipline and lawlessness. These people have nothing to live for so they putting everyone’s lives at risk…”. One person named the community directly in their comment, explicitly saying, “Pure dunce living in Jones Town”.

4.3.2. Derogatory Remarks and Dehumanizing Metaphors

Derogatory remarks have long been used as a means of devaluing various characteristics and attributes of the marginalized associated with their perceived social identity (

Reutter et al. 2009;

Goffman 1963). During this process of stigmatization, there is often a separation of various individuals into distinct or ‘other’ categories and the development of intolerance, exclusion, and other separatory sentiments against a targeted population. In this study, a substantial cross-section of comments produced names associated with animals and pests. It was recognized that these derogatory discourses often carried a dual connotation, whereby these basal labels were also used to frame those who failed to adhere to public health guidelines as being of low intelligence and incapable of thinking critically. This was espoused in the following statement, whereby a commenter described the behavior in the video as, “A total display of low IQs way below that of any insect!”.

It was debasingly implied that the marginalized collectively approached decision-making poorly because they engaged in actions instinctually, similar to the animals and creatures they were being compared to. One commenter stated, “It’s what’s called Herd Mentality like if there is a Stampede. All the Buffalos runs the same way. Right or wrong”. Indeed, there was a general expression of dehumanization toward the low-income populations and communities featured. This was expressed by the following comment from one user who associated the decision of informal sector traders to continue to engage in work-related activities to one an animal would make: “Kiss my teeth, Shake my Head. When they are dead let them continue to hustle. They are like goats”. Such sentiments suggest their behavior as incapable of changing, that they were mindless and that they were morally wrong for the decisions they made. This simplistic meta-narrative led to expressions of outrage and calls for punishment for those not complying.

4.3.3. Disproportionate Punishment

In addition to various forms of derogatory sentiments, the notion of othering against ostracized subgroups was further compounded through the suggestion of disproportionate punishment. These comments were often draconian in nature and seemed to have surpassed the realms of traditional discrimination and marginalization, as passive expressions evolved into calls for active forms of punitive action and retributive justice. Quite significantly, these expressions of disproportionate punishment involved the complete or partial removal of human and or legal rights as expressed by the following user: “Shut your eyes lawmen and beat them with the baton”. Additionally, expressions of disproportionate punishment were associated with there being little to no worth to the life of persons in the inner-city communities depicted, with some comments even calling for their death in explicit terms, as evidenced by the following user: “I heard that the Prime Minister of the Philippines told the police to shoot and bury persons who do not ordain to Social Distancing measures. This could be what they need to comply with these measures”.

Many comments stated that residents were undeserving of state resources such as healthcare, with some making the exaggerated claim that allowing persons to die would be beneficial: “Leave them, let them die. It will be better for the government”. While not verifiable, it is alarming to note that one person who claimed to be a healthcare worker stated they would deny medical treatment to persons from areas depicted in the videos, saying, “I won’t be wasting my time or meds on stupid people”. Another comment harshly expressed the idea of the destruction of their communities, stating, “I always said they need to drop a bomb in this area so that it can start over from scratch”.

These numerous calls for the enactment of punitive measures again proposes the idea that marginalized inner-city residents are incapable of doing any better, which is often reasoned to be due to underlying perceptions of them as mentally incapable and low in intelligence. This can be reflected in the following comment: “Lock up everyone and their mother. Kiss my teeth, they are so dunce”, which also espouses the belief that entire communities should be locked up whether compliant or not.

A possible reason for these expressions of disproportionate punishment may be attributed to the widely held belief that persons from these communities are more likely than other groups to spread the virus, and hence must be either separated or eliminated as a means of containment. This is expressed in the following comment: “The Member of Parliament responsible for this area is ridiculous and these people do not value their life. They need to send the army to close off the entire area as we will see more cases very soon if this continues”. These generalized expressions again highlight the shared negative perceptions of geographic space and the collective population that occupies it.

4.3.4. Overt Racism and Internalized Racism

Some derogatory and dehumanizing comments were seen to have made direct reference to the racial identity of the marginalized populations depicted in the videos. Such racialized comments explicitly posited that non-compliance with social distancing among Kingston’s urban poor was directly attributable to their black racial identity. These comments prominently featured overtly racist caricatures and overtones that expressed a number of unduly negative black cultural stereotypes. What is interesting to note was that most of the comments did not appear to have been made by members of a privileged racial majority, that is, those belonging to a different, typically dominant (e.g., white) racial identity with embedded hegemonic power. Rather, they seemed to have been made by Afro-Jamaicans themselves, that is, members of a black majority society (98.1% black/mixed) with a self-controlled black majority government (

Statistical Institute of Jamaica 2012). This was assessed based on the contextual nature of the comments, such as the linguistic markers of Jamaican nationality and origin, and the inclusion of direct references of belonging to a collective identity (e.g., “our communities”).

Therefore, such comments may not only be classified as overt racism, but may also be deemed instances of internalized racism and internalized oppression. Both concepts are similar and are said to occur when institutionalized and systemic forms of racism and oppression result in marginalized groups turning on themselves, often without being self-aware of it (

Padilla 2001;

Lipsky 1977). Based on the racialized rhetoric used in the comments, it was readily apparent that members of the same racial population (i.e., Afro-Jamaicans) engaged in the enactment and acceptance of negative societal beliefs, tropes, and stereotypes about themselves (such as being impoverished, foolish, defiant, etc.). This was best exhibited by one comment, which stated: “Hungry, broke and needy…Poor black people…”. Other comments seemed to be more covert in their expressions of racialized bias, with one seemingly condemning the actions of those depicted breaching social distancing and curfew orders by posing the question: “why black people stay so [why are black people like this]??”. Another online user went even further by universally panning all black majority countries the world over, claiming that breaches of social distancing were: “…happening in every black country, not only Jamaica…”.

Throughout such comments, there was a disturbing pattern of insinuating that blackness was synonymous with outright defiance of rules and systems: “Black folks hate structure, defiant just to be defiant”. The same comment went on to say, “…It’s ok though, natural selection always win[s] in the end”, threateningly implying that such stereotypical attitudes and practices of black communities are not natural and will result in their self-destruction in the future, and that such a disastrous outcome would be a preferable one. There were also comments that associated being black with being in possession of too low a level of intelligence to be able to follow government mandated health measures, as demonstrated by a comment that stated, “Black people too foolish.” Comments such as these unjustly implied that all black persons possessed inherently diminished capacities for logic and reasoning, not that dissimilar to the previously discussed meta-narratives that utilized descriptions of animals or animal activity to imply low intelligence.

4.3.5. Political Differences

The development of political patronage in the form of collective clientelist relationships between marginalized low-income residents and the country’s two main political parties (Jamaican Labor Party and the People’s National Party) has dominated the social fabric of inner-city communities in downtown Kingston since the 1960s. Such practices have perpetuated enduring socio-spatial division among fragmented communities of the urban poor who compete for partisan-controlled resources and income-earning opportunities. These circumstances have been responsible for heightened social tensions that have often culminated in various forms of political violence throughout the years, ultimately serving to cement partisan loyalties among a socially excluded and highly marginalized population of urban dwellers (

Sives 2002).

This bipartisan political divide is so deeply embedded in the social and cultural fabric of Jamaican society that they are not only limited to the streets of Kingston, but were also brought up in online discussions of residents from these areas. A number of commenters pointed out the political affiliations of those depicted in the videos: “Notice it’s two of the political strong areas [strongholds]. JLP and PNP. Always…Always”. Some also argued that their non-compliance was directly related to their political allegiance. One commenter questioned whether “…because it’s a PNP area, that’s why they won’t listen to a JLP prime minister?”. Another simply stated, “PNP, what do you expect?”. Others took this idea further, insinuating that they shared an enhanced proclivity toward deviant behavior that was directly attributable to their political identity, stating that those in the video were a “… Bunch of PNP dunce. Just waiting to loot”. Commenters also suggested that non-compliant behavior was due to a culture of social protection and welfare dependence: “Education has nothing to do with their behavior. It’s the political freeness and entitlements.”

4.4. Discourses of Social Diversity

4.4.1. Counter-Narratives

Although most comments were classified as eliciting some form of negative sentiment or remark, it is important to mention that a small, but significant, minority of them were characterized by positive and constructive views. The latter often took the form of counter-narrative messaging that provided a powerful rebuttal to the predominantly negative portrayal of the marginalized populations depicted, and provided ardent criticism of the many discriminatory and dehumanizing notions that were being expressed.

A number of comments rightly recognized the role that dire prevailing socio-economic and socio-political circumstances might have played in exacerbating the vulnerabilities of the marginalized. Persons highlighted how it would not be feasible for most of the urban poor to work from home given their high rate of self-employment in informal sector activities, which typically do not provide a sufficient level of financial stability and savings accumulation to permit this: “A lot of people are self employed. It’s called a hustle aight. A lot of these people can barely even afford a day’s meal. Imagine quarantining for a month without no income”.

Therefore, rather than being seen as acts of defiance, their non-compliance with public health guidelines may have simply been the result of having access to few, if any, alternative livelihood options other than to work in dangerously crowded conditions: “It is not that the virus nuh real, or that dem nuh care, the truth is you and I can afford to stay home because we don’t have to find our food daily. Some of those people out there can’t buy [food] for more than a day or two. They have kids to feed and so they are trying to earn a dollar. I am not saying it is right but some of them have no choice.” The plight of the urban poor during COVID-19 can therefore be best surmised as coming to terms with the following question posed by one commenter: “Do you stay home and die from hunger or do you try to find food knowing that the virus is a threat?”.

One commenter also argued that the breaking of curfew orders by marginalized populations in order to leave their home and socialize may be justified, acting as a potentially important mitigation and coping strategy against issues related to mental health, anxiety, abuse, and even the starvation that may arise from persons living together in the cramped, confined spaces of the tenement yards and public housing complexes occupied by the city’s poor: “Many of these people are genuinely hungry and their only outlet is to [engage with the] commute [community] and stave off the hunger with socialisation”. The same person made it clear that the “Law is law and we got to learn to obey but still we got to be mindful of their reality”.

There were also some that acknowledged the destructive nature of the various negative remarks that were made and called for greater understanding and awareness of issues of systemic inequality. In direct retaliation to a comment that implicated non-compliance with diminished intelligence and race, one online user strongly denounced such notions by replying, “You are the dunce. Stop calling God’s people stupid. We as black people have been abused and neglected”. In a similar vein, another said that “… It’s not a matter of dunce cause if human don’t eat how [are] we gonna live[?]. Stop calling the people them dunce…To be honest y’all sound dunce as well”. We, therefore, saw some pushback against many of the derogatory and dehumanizing narratives expressed in the public discourse. Some recognized that a person’s supposed ‘unruliness’ and ‘defiance’ could be attributed to tangible issues they were facing, as opposed to bigoted notions and assumptions.

The role of the government was also heavily criticized. It was frequently brought up that the state has effectively neglected inner-city populations and has not adequately assisted them in properly adjusting to the ‘new normal’: “The government is supposed to help those that are self employed with financial assistance. They should have given the people some time to get prepared…”. It was also noted that if the state were more proactive in attending to their needs, breaches of social distancing might have been better avoided and “… then we would not have had this situation”. Some also claimed that the government themselves exercised bias in the implementation of their policies, enforcing curfew orders for certain poorer communities while ignoring breaches in more affluent areas: “Why they never curfew [areas located] uptown when there were reports of a case [there]…?”.

4.4.2. Denouncing of Media Bias

A number of these counter-narratives also pointed out the disproportionate geographic bias apparent in the news stories. Some commenters explicitly recognized that the news stories only focused on instances of non-compliance in the downtown area of West Kingston, featuring persons exclusively belonging to its poorest communities. Many comments echoed the question, “Why do we always have to shine the light on the ghetto”, given the fact that, “The virus is all over the island”, and that, “whether you rich or poor, all will feel it. There is no discrimination or classism with Corona”.

Condemning the reporting to be one-sided and biased, and noting possible discriminatory overtones, many called for the reporters to be fairer and more balanced in their coverage: “Downtown is a huge problem yes, but more balance is needed in the reporting. Everybody has an equally important part to play from the highest to the lowest”. Many directly questioned why middle- or upper-income areas of the city were ignored by reporters: “Why do we never see them show uptown people disobeying orders?”.

The biased reporting was noted to be especially problematic due to its potential to perpetuate damaging stereotypes about the marginalized populations depicted: “…this only serves to strengthen the stereotype that only ghetto people in Jamaica [are] unruly. A more balanced report would show that’s not the case”. Some noted that more balanced reporting would also have the potential to lead to an increase in the rates of compliance as “… It would show that everyone needs to comply, not just poor people”. One comment even made the astute point that reporters from the news agency were themselves complicit in the breaching of social distancing guidelines and wearing of PPE, ironically failing to meet the same expectations of compliance with public safety for which they were chastising marginalized populations: “The reporter is downtown with zero protection. So…half a dozen a one, 6 of the other [the actions of both are producing the same outcome]”.

Many comments noted that reporters should attempt to make a concerted effort to showcase breaches of social distancing in other areas where they are known to be occurring and not just the ghetto: “Why don’t you go outside the banks and supermarkets uptown where people are lined up closely, waiting to go in?”. Giving their own explanation for the biased coverage, one person reasoned that: “Everywhere people are disobeying the orders but they wouldn’t go uptown and showcase it like that. No one would even stop to answer them”. This comment suggests that the choice of ignoring uptown areas may have been a deliberate one made by reporters, as focusing their efforts downtown allowed for the targeting of a vulnerable and exploitable population.

5. Discussion

The video news stories incited significant controversy and divisive public dialogue as was demonstrated in the comments analyzed. Given that the online comments provided some level of anonymity, they were deemed to have been the perfect means for capturing authentic self-expression, acting as a proxy for the prevailing cultural zeitgeist of Jamaican society. The opportunity for unfiltered speech provided in the virtual space therefore served as the ideal playground for understanding the latent social tension that may be festering within Jamaica, and how it is affecting marginalized subgroups as they come to grips with the new social realities spurred on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Indeed, the comments saw many unencumbered expressions of identity politics imbued with perverse undertones of exclusion. This reflects a relatively polarized society marked by social divergence and was vividly expressed via comments that explicitly and implicitly evoked meta-narrative discourses of difference and division. An inevitable outcome of this sort of social divergence is often the construction of an ‘us and them’ dichotomy, and this notion was commonly demonstrated in the rhetorical endorsement of spatial, social, political, or economic separation. In this regard, both the news stories and many of the comments that followed were strongly representative of sentiments surrounding the process of othering. In this situation, marginal groups were discursively constructed as the ‘threatening other’ and demonized for their lack of compliance with social distancing practices.

Throughout the comments, it was often implied that non-compliance stemmed from a number of negative personal traits, attitudes, and behaviors purported by many to be intrinsic qualities among those who live and work in marginalized inner-city communities in Kingston. Such associations between moral character and place, race, political, and class identities clearly represented instances of blatant stereotyping and denigration. It is likely that the inherently biased framing of the news stories would have influenced commenters to engage in the ensuing discourse along similarly prejudiced lines. Such negative and prejudicial associations with Kingston’s inner-city communities is certainly not a new development, with the literature noting multiple dimensions of marginality having contributed to systemic othering, discrimination, and exclusion of persons from the city’s downtown areas for decades (

Spencer et al. 2020;

Altink 2015;

Hunter 2010).

In fact, the disproportionate focus of these news stories on downtown’s poor districts along with their resoundingly negative portrayals in media narratives may be indicative of the occurrence of poverty porn (

Plewes and Stuart 2009), whereby the actions of known vulnerable groups, such as the poor, are deliberately featured in caricaturistic ways that are in line with prevailing societal biases and stereotypes so as to provoke an emotional response (in this case outrage) to appeal to large segments of the viewing public (

Mooney 2011). The media’s sole focus on the poor may have also been driven by the relative ease and impunity with which they could access and feature them. Reporters may have taken advantage of impoverished residents’ innate powerlessness and inability to shape the narrative, thereby exploiting those featured and ultimately perpetuating varying degrees of victimization, stigmatization, and objectification (

Seymour 2009). This would stand in contrast to middle- and upper-income areas of the city that command more power, resources, and agency, and which could have potentially offered resistance through public, and even legal, backlash if they were instead thrown into the spotlight.

So, although the range of stereotypical remarks made against downtown residents may have been influenced by the apparently biased content of the video news stories themselves, they are more likely the result of reflexive reactions based on long existing societal biases that have transfixed wholly negative place images of downtown areas of the city in the public consciousness. While the biased opinions evoked in the news stories might not have created such negative sentiments, the sensationalized and unbalanced narratives used to frame the actions of the marginalized populations may nevertheless infect the public discourse. Given the prominent public attention garnered by the news stories and the status of local media houses as ‘trustworthy institutions’, the biased notions expressed may be legitimized and validated. Ultimately, they may be liable to become more deeply accepted as part of normative culture and propagated more vigorously and intensely in public discourse (

Lentin 2008;

Van Leeuwen and Wodak 1999).

It is important to note that the biased accounts and stereotypical notions expressed in the videos and ensuing commentary should not be considered as causing the systemic problem of societal discrimination in Jamaica. Rather, they are more so the symptoms of systemic forms of maltreatment that stem from ‘real’ external forces of oppression imposed on the vulnerable by those with access to power and privilege (

Salzman and Laenui 2014). While not considered to be a direct causal factor, bias and stereotypical accounts may still perpetuate societal discrimination by coloring the public discourse against the marginalized, which in turn can have devastating effects on their collective socio-psychological well-being and cultural practices. The dehumanizing rhetoric has been shown to lead to negative self-evaluations among the marginalized as they may become conscious of them. Some may even believe them to be true, potentially leading to widespread self-destructive tendencies that may be self-fulfilling (

Padilla 2001).

The articulation of stereotypical notions that principally targeted downtown residents ultimately conveyed a lack of compassion and understanding. Several commenters failed to understand the inequity in access to financial resources; the dependence of the urban poor on the informal sector, which largely relies on in-person transactions; and the lack of substantial or dependable social relief from state institutions for vulnerable populations. Such circumstances are known to make it difficult, and in some cases, impossible for persons to properly abide by social distancing guidelines, curfew orders, and other measures intended to safeguard the public health. However, by pinning the issue on identity (place, race, class, etc.), many commenters did not recognize possible legitimate reasons for the actions of the marginalized, which they wrongly labeled as acts of ‘defiance’ and ‘unruliness’. By blaming non-compliance with COVID-19 protocols on certain identity politics, and not the slew of possible legitimate concerns (which if addressed could increase compliance), public health issues as well as social tensions arising from COVID-19 are likely to persist or even worsen.

It is important to note that some comments did engage in a counter-narrative message, rejecting the narrative consensus of biased viewpoints presented both in the reporting and the commentary itself, while also acknowledging the social diversity that exists in Jamaica—in particular, the unique life circumstances and challenges faced by the marginalized. This was indeed positive, demonstrating that persons were constructing and engaging in critical perspectives of the prevailing media narrative, such that alternative views were not drowned out and the negative sentiments expressed toward the marginalized were ultimately not seen as the self-evident social reality, or ‘doxa’, that they were portrayed as by the media (

Bourdieu 1999).

However, it remains that stereotypical notions and dehumanizing remarks dominated the public discourse online, such that the majority consensus was the othering of the marginalized and the demonization of their actions. This is deeply troubling knowing the already constrained options available to persons in those communities. If such negative public discourses continue to spread, as is common during times of crisis, it is possible that the marginalized may be forced to contend with even further increases of instances of discrimination and heightened exclusion from critical service provision, which would certainly prove to be a disastrous outcome during a worldwide pandemic.

6. Conclusions

Media narratives in public discourses can be regarded as potentially dangerous in propagating stereotypical notions around marginalized groups. The unbalanced and unfairly prejudicial representations of Kingston’s population of inner-city residents fed on, and in turn, perpetuated notions of social divergence and stigmatization against this already vulnerable population. This was demonstrated in the discriminatory and derogatory sentiments expressed in the comments made in response to news stories, which served to subject the marginalized to even more societal scrutiny and condemnation during the time of national crisis experienced in the first few months of the pandemic.

Although such bigoted expressions were limited to an online space in the form of a (YouTube) comments section, it is important to note that this does not negate the possibility for such messaging to translate into real world consequences. It may certainly serve as a form of confirmation bias among the prejudiced who see the multiple instances of discriminatory stereotypes being expressed toward these groups as evidence that their viewpoints hold true and are representative of the public consensus, thereby cementing them further. This process leads to a chronic cycle of othering, which, if not addressed, may continue to infect the public consciousness and compromise the potential for an integrated society.

These findings ultimately suggest that media coverage potentially influences social divergence, therefore countering the core principles of inclusiveness and integration. Accordingly, media coverage should be more sensitive to the portrayal of vulnerable marginalized groups. This may entail the development of regulation aimed to curtail societal, political, and economic bias by local news agencies, and enforced by independent commissions. Pervasive and damaging cultural stereotypes that underlie othering may also be actively addressed by the state, who may be able to engage in collaborative partnerships with NGOs and the local business sector to support public sensitization campaigns aimed at promoting greater levels of understanding for marginalized groups and the acceptance of their diverse lived experiences.

It should be noted that this study faced certain limitations. Given its exploratory research design, the results were far from being considered quantitatively representative. Additionally, although the final pool of videos and comments was determined to be substantial enough to perform an adequate level of qualitative analysis needed to produce solid conclusions, the study may have still benefitted from having access to a larger dataset.

However, there is potential for future work to build on this exploratory framework by expanding the study to other mediums such as newspaper articles, blogposts, and other forms of social media such as Facebook and Twitter. This may also entail the integration of more quantitatively based methods that employ the use of computer-assisted tools to produce more empirically substantiated findings. In particular, the use of statistically derived data and empirical testing may help to produce more holistic understandings and provide a generally clearer picture of the extent to which biased media narratives and public sentiments may enhance marginalization and othering during periods of crisis.

It may also be worthwhile to explore the potential impact of these public discourses from the perspective of both the general population and those who are directly victimized by it—that is, the marginalized themselves. This may be helpful in determining the extent to which these external processes may come to be internalized. For example, whether the public may be swayed and swept up by the prevailing public discourse so that exclusionary sentiments and actions become intensified. In turn, it would be interesting to explore how discourses may affect the socio-psychological well-being of the marginalized as their self-identity, self-evaluation, self-esteem, and collective sense of social belonging in mainstream society could be diminished so that divergence may be worsened even further.