1. Introduction

The position of people with intellectual disabilities in scientific research has changed significantly in recent decades. Whereas for a long time they were not involved in research (others spoke for them), since the end of the 1990s, we have witnessed efforts to take a different approach. Their involvement in this regard has morphed from being exclusively research participants to gradually becoming more actively involved in the various stages of the research process.

Bigby et al. (

2014a) differentiate between three different approaches to how people with intellectual disabilities are actively involved in research: (1) an advisory approach (people with intellectual disabilities provide advice to academic research teams), (2) a leading and guiding approach (people with intellectual disabilities initiate, lead, and execute their own research about issues important to them), or (3) a collaborative group approach (people with intellectual disabilities work in an equal partnership with academic researchers). Each of these approaches creates opportunities, in different ways and to different degrees, for people with intellectual disabilities to influence research and help take decisions relating to aspects such as research topics, design, and used methods.

The literature on this topic cites various good reasons why it can be both important and valuable to have people with intellectual disabilities take an active role in research projects. For example, the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (

United Nations 2006) emphasises the right of people with disabilities to be involved in issues affecting them. In addition, being actively involved in scientific research can have a beneficial effect on the individuals directly involved (e.g., learning new skills, gaining insight into the experiences of (other) people with intellectual disabilities) and by extension on other people with intellectual disabilities and by extension on people without disabilities working with the latter (

Frankena et al. 2015;

Stack and McDonald 2018). It is also experienced that involving people with intellectual disabilities can contribute to the quality and relevance of research. For example, researchers with an intellectual disability can have a ‘technical’ contribution by developing materials that are appropriate for the research and its participants (

Nind 2014;

Frankena et al. 2015;

Puyalto et al. 2016). Individuals with intellectual disabilities are also recognized as advocates who can help to concretize more abstract terms such as autonomy, empowerment, participation, and inclusion, bring good practices to the fore, and who take the lead in uncovering barriers (regarding, for example, accessibility, supportive relationships, or transition to adulthood) (

Chalachanova et al. 2021).

When people with intellectual disabilities take on an active role, the term often referred to is inclusive research. In an article from 2018, Walmsley et al. attempted to define a ‘second generation’ of inclusive research, taking into account the evolutions that have occurred since the beginning of the 21st century. According to these authors, inclusive research can be described as follows (p. 758):

Research that aims to contribute to social change, that helps to create a society, in which excluded groups belong, and which aims to improve the quality of their lives.

Research based on issues important to a group and which draws on their experience to inform the research process and outcomes.

Research which aims to recognize, foster, and communicate the contributions people with intellectual disabilities can make.

Research which provides information which can be used by people with intellectual disabilities to campaign for change on behalf of others.

Research in which those involved in it are ‘standing with’ those whose issues are being explored or investigated.

Practices of inclusive research are increasingly being realized in different places around the world and with different ‘target groups’. In this regard, we are inspired by research centres and groups with years of experience. The fact that they have realized many projects, built a large network, presented and published a lot but also (and above all) that they have been able to exert a lot of influence on local practices and policies offers opportunities to learn from them. We would like to briefly describe two inspiring examples below. To begin with, in Ireland, we can learn from the intense cooperation between the National Federation of Voluntary Service Providers, Trinity College Dublin, and University College Cork.

Iriarte et al. (

2014) and

Salmon et al. (

2018) report on the pathways this network developed to conduct research about topics that are important for persons with disabilities. They worked with training workshops, organized a continuous dialogue about their projects, used creative tools (such as role plays) to develop skills of researchers and co-researchers, worked hard to make sense with the teams of the data, and presented their work in local, national, and international meetings. At the same time, these researchers are able to keep a very critical stance towards their own work not wanting to become the very type of research it aims to challenge (

Salmon et al. 2018). A second example is located in the USA, where

Nicolaidis et al. (

2019) report on the practices of AASPIRE-USA regarding trying to develop guidelines for the promotion of the inclusion of autistic adults as co-researchers. They put a strong focus on being transparent about partnership goals, clearly defining roles and choosing partners, creating processes for effective communication and power sharing, building and maintaining trust, disseminating findings, encouraging community inclusion, and fairly compensating partners. It is important to learn that for persons with autism (the group that is often strongly entwined in a clinical model), the time has come to participate in research. The lessons learned in research projects with people with autism can help us to make the framework for research projects and the communication about the projects clearer for colleagues-researchers with intellectual disabilities as well.

As a result of the growing attention to inclusive research and the increase in research initiatives with an inclusive approach, the knowledge shared (through publications) on this topic is growing. The publications can be roughly divided into two groups. There are articles that primarily focus on personal experiences of inclusive research and reflections on collaborative research (e.g.,

Strnadová et al. 2014;

Dorozenko et al. 2016;

Riches et al. 2017). In addition, other publications attempt to arrive at assertions that can be generalised across inclusive research initiatives, such as attributes that should be taken into consideration when conducting inclusive research (

Frankena et al. 2018), competencies that are considered important for researchers with and without intellectual disabilities in inclusive research initiatives (

Embregts et al. 2018), and contextual and team-level factors and processes that foster and maintain inclusive research (

Schwartz et al. 2020).

Through this article, we want to align ourselves with the tradition of incorporating personal experiences. For the first two authors (both researchers, of which one has an intellectual disability), this article represents the culmination of an extended period of collaboration within a research project (see

Section 2.2). The first author positions herself in a tradition of doctoral students opting for a more inclusive approach in their research work. Already in 2008, Björnsdóttir reported on the tensions that inclusive research during a PhD trajectory evokes within a competitive academic environment and the danger of academic researchers falling into the same trap of the exclusion that they criticize society for (

Björnsdóttir and Svensdóttir 2008). By focusing on the tension between inclusive research and traditional ethical guidelines at research institutes and universities, Morgan wanted to make future PhD researchers aware of possible incompatibilities linked to, e.g., disclosure, the tension between empowerment and protection, and the application of shared partnership, equality, and transparency within an academic context (

Morgan et al. 2014). Moreover, Dorozenko’s recent call for PhD students working with inclusive research to have sufficient reflexivity and critical reflection (e.g., regarding the risks of repeating oppressive power relations) was very inspiring for the collaboration described here (

Dorozenko et al. 2016).

The aim of this article is to reflect on our own research collaboration by exploring our personal experiences of how our collaboration in research works best, as well as the benefits that our collaboration has brought to us personally as well as to the quality of the research. We hope that our experiences can provide support to other researchers who wish to set up and conduct inclusive research. This article was realised thanks to the substantial contributions of several people who are all co-authors. Mark and Miriam form the research duo that worked together on a research project for several years (see

Section 2), and for this article, they reflected on their collaboration. Geert, Karin, and Alice were involved in this research project as supervisors and advisors. Not only did they advise the research duo on ‘technical’ research issues but also on conducting research inclusively. Christine was asked to help the research duo compile and situate experiences (see

Section 3). With regard to the writing of this article, Geert, Miriam, and Mark took the lead, and the other three co-authors reviewed previous versions of this article.

2. Context

2.1. The Research Duo

Mark and Miriam both work as researchers at the Philadelphia Care Foundation (PCF) in the Netherlands. The PCF is a care organisation for people with an intellectual disability, which offers a wide range of support services throughout the Netherlands. Over a period of almost four years (December 2017–October 2021), Mark and Miriam worked together on a research project into the experiences with an online support service of people with intellectual disabilities living independently (more on this in the next section). In addition, Mark works several hours a week as an assistant on other projects within the PCF. Mark and Miriam introduce themselves below. Mark: ‘I am 45 years old. I was born prematurely and for a long time I believed I had a developmental disorder. I went to a special education school. For a long time, I felt like I had a hard time making friends, but I did have contacts with other people. Once I finished school, I had various jobs in administration. I often felt like I wasn’t taken seriously at work. I also had the feeling that I was only half-participating in society. I had the feeling that something was wrong, but I did not know what it was. In 2005 I was diagnosed with PDD-NOS, a form of autism. That’s how I ended up coming into contact with Philadelphia [the service organisation]. Then things started to change. There were opportunities at work to focus on my talents in a partially sheltered way, I was able to develop myself. This was enhanced when I joined various client councils within the organisation. I felt I was being taken more seriously. I mattered. Through people at the client council, I came into contact with Miriam in 2017. She was looking for a colleague to conduct research together. At the time, I had no experience with research, let alone scientific research. Back then, I couldn’t have told you what research involved. And then the ball of cooperation started rolling’. Miriam: ‘I’m 40 years old. I went to a mainstream school and completed studies at university, where I was able to gain a lot of knowledge and skills in the area of scientific research. After my studies, I did various jobs conducting research. Sometimes these were projects in which we tried to involve the ‘target group’, such as young people in mainstream education. However, these were not truly inclusive projects. As such, when I joined Philadelphia in 2016 I had no experience with inclusive research’.

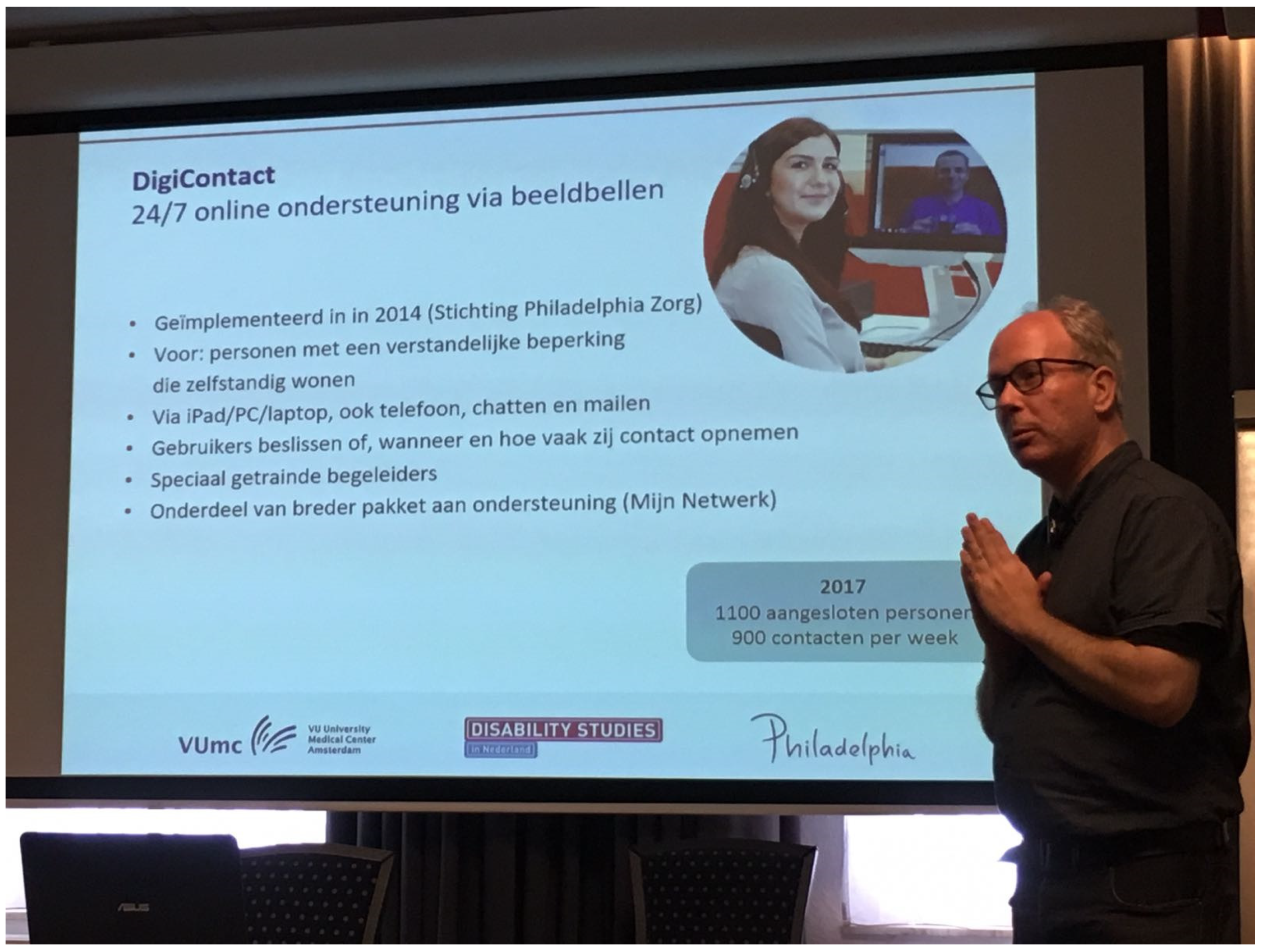

2.2. The Research Project

The project that Mark and Miriam worked on involved research into the online support service DigiContact. This service is offered by the PCF as part of a broader package of support services for people with intellectual disabilities living independently (in their own homes) (

Vijfhuizen and Volkers 2016). DigiContact offers 24/7 remote support, where people with a support need can contact a team of specially trained support workers via either an app or link on their mobile phone, tablet, or computer or via a standard telephone. The aim of the project was to compile knowledge on the experiences of both support users and professionals of DigiContact regarding the potential value of its support for people with intellectual disabilities living independently. During the course of the project, five sub-studies were performed of which each focused on a different question. A scientific article was (or will be) drafted in English on each sub-study (

Zaagsma et al. 2019,

2020a,

2020b,

2021).

The research project started in 2015 with a different researcher duo. After one year, both members of this duo left the project because neither of them wanted to continue working as researchers. After this, Miriam started working on the project in February 2016. During the first year, she worked with another co-researcher for several months. Mark was recruited as a co-researcher in 2017. For Miriam, the research project formed the basis for her PhD at the Amsterdam UMC (Vrije Universiteit). Throughout the project, she was able to devote 32 h per week to the research project. When Mark was recruited, he was offered a contract to work on the research project for an average of 8 h per week. He also worked a varying number of hours on other projects within the PCF. Besides Miriam and Mark, three senior researchers (fourth, fifth, and sixth author) were involved in the different sub-studies into DigiContact. They provided advice for the research and supported Miriam in her PhD.

3. Materials and Methods

In this article, we reflect on the personal experiences of Miriam and Mark with conducting research together during the research project on the potential value of 24/7 online support. By doing so, we align ourselves with the tradition of an auto-ethnographic approach, in which personal experiences are described and analysed in order to understand broader cultural experiences (

Ellis et al. 2010).

During the course of the research project, data on the collaboration were logged in various ways. To begin with, both Mark and Miriam independently kept a logbook in which they wrote down their personal experiences, thoughts, questions, doubts, and difficulties on a weekly basis. During the first weeks of the project, Mark was supported by Miriam on how to keep a logbook (e.g., by discussing together what to note, when to do this, with how much detail, etc.); after this, he continued to do this by himself. In addition, Mark and Miriam had regular conversations together about the research and their collaboration in particular. These conversations were not always planned in advance and did not have any fixed structure. Notes of these conversations were recorded in the logbooks.

In preparation for this article, five meetings were organised and held (in the spring and summer of 2020), in which Miriam and Mark reflected on their collaboration under the guidance of a moderator (3rd author). This moderator was able to reflect on their experiences and ask questions from an outsider’s perspective. At the start of these meetings, the moderator, Miriam, and Mark discussed topics that would be interesting to explore. Examples of topics were: expectations of conducting research together, how different research activities (e.g., analysing data) were carried out, and perceived facilitators and barriers in the process of collaborating. Before each meeting, the moderator prepared a list of questions she could use to fuel the conversation when needed (e.g., ‘What were difficult moments during the project (and why)? What are you proud of (and why)?’). The notes in the logbooks were used as input for the meetings, with Mark and Miriam going through them in advance to refresh their memories. To prepare for this, a plan of action was drawn up by the researchers together. This plan included a guideline regarding what to do (e.g., what to pay attention to, how to make notes of topics that seemed important) and a plan on when to do this (the work was spread out over multiple shorter sittings because the collection of notes was quite comprehensive). Following up on this plan, the researchers worked independently from each other to review their own notes without needing further support. The five meetings took place remotely via videoconference, on account of the COVID-19 measures in place at the time. Three of the five meetings were conducted jointly. In the other two meetings, the moderator talked with each researcher individually, focusing in particular on elements that were related to Mark and Miriam’s unique and highly personal perspective. Each meeting was recorded and subsequently transcribed by an external agency.

The transcripts of these five meetings and the logbook notes formed the research material. To decide on which reflections and experiences to present, Miriam and Mark went through the material while keeping the three topics of reflection in mind (i.e., how inclusive research can be organised, the possible benefits of the collaboration for the researchers involved, and the possible impact of the collaboration on the quality of the research). They started this process separately from each other. Both of them read all the transcripts and notes. To assist with ease of comprehension, Mark also listened to the audio recordings of the meetings, as this helped him retain his attention and grasp the meaning of what was being said. They both used marker pens to highlight parts of text on a given topic, always writing the gist of the text in the margin. They each made a list of the experiences they personally found important. These lists were shared with each other by e-mail. As a next step, Miriam and Mark compared and discussed the experiences on their lists in order to come up with a joint overview in which their experiences were integrated. This process took place (mostly) via videoconference calls due to COVID-19 restrictions being still in place. This overview was shared with the other authors in order to decide together with them on which experiences needed to be highlighted in this article. The starting point in this was to present experiences that we were convinced would interest other individuals involved in inclusive research.

5. Discussion

At the start of this article, we explained that we would reflect on three topics, based on our personal experiences: (1) how best to organise inclusive research, (2) the possible benefits of the collaboration for the researchers involved (Mark and Miriam), and (3) the possible impact of the collaboration on the quality of the research. In this discussion, we first look at what we can infer about these topics from the research material presented. We then briefly compare our results with the recent research literature on inclusive research.

Regarding our experiences on how to organise inclusive research, it is clear that this was difficult during the start of this research project. For example, the first research duo quit after a year, the co-researcher of the second duo quit after a few months, and after that, it took a long time before Mark and Miriam could really start working together. Our experiences led to several insights. First, we experienced that not everyone is motivated, ready, and able to become a member of a team doing inclusive research. It is therefore important to recruit researchers and co-researchers who are suitable partners in inclusive research. It also underlines the importance for organisations and research institutes that want to engage in inclusive research to provide education and training on inclusive research methodologies (

Iriarte et al. 2021) for researchers (both academic researchers and co-researchers). Second, we learned that hiring people with disabilities as paid researchers can come up against various administrative hurdles. A research job is often temporary and not always stable over longer periods of time. Many people with disabilities are caught in the ‘golden safety net’ of social security: they have a good monthly income; however, this can be at the expense of further self-development and taking on new challenges. Third, we learned that the party who commissions the research (in this project, a large service organisation) can play an essential role in inclusive research, a role that does not have to result in interference with the body of the research. In this project, the PCF really ‘stuck its neck out’ for the final duo. For example, Mark was offered more than one project to provide him with a stable income. In addition, the unavoidably slow pace of inclusive research was well understood: more time was allocated to the research project. In this project, introducing a job coach proved to be a golden asset. This job coach could work in a supportive manner in the function of what

Morgan et al. (

2014) named transparency. The job coach could also, especially during the first phases of the research, help to inform and clarify certain aspects. This intervention allowed both researchers to really work as colleagues, and thus this aspect of power imbalance could be mitigated.

As regards the benefits to both researchers of conducting research together, the research data show benefits to the co-researcher: Mark got a job that allowed him to have a more direct influence on the quality of life of people with disabilities. A (research) world opened up to him in which he gained respect, and he states that this had a great influence on his self-confidence and his ability to acquire new skills. He learned to listen carefully to people, ask the right questions, and see that the perspective of the experienced expert could really contribute something to the research. The academic researcher also personally benefitted from the opportunities that were created for Mark to have a voice, to exert control, and to make decisions, as this made sure that this project was not ‘just another’ PhD that only reflected the perspective of non-disabled experts or researchers (

Björnsdóttir and Svensdóttir 2008;

Dorozenko et al. 2016). The academic researcher also learned from their long-term collaboration about ways in which they could best work together and conduct research together. In this regard, it was especially difficult situations from which she could learn, such as a previous collaboration with a different researcher with intellectual disabilities in which the roles of being a supporter and being a colleague became too intertwined.

Finally, as regards the quality of the research, we would like to emphasise in particular the fact that Mark, as a co-researcher, seized opportunities through his involvement in various projects to take methods from one research project to the next. For example, methods for visually grouping data were contributed in a very creative way and provided additional depth. In this regard, we go further than

Björnsdóttir and Svensdóttir (

2008) who state that well-executed inclusive research is of the same value as non-inclusive research. In our research project, the inclusive approach led to a higher value—something that can be deduced, for example, from the very high number of articles that were eventually published within this PhD. In addition, the slow pace at which the research advanced also ensured that all research steps were prepared and experienced more intensively by both researchers (see, for example, the way Mark describes how research questions and interview questions were meticulously coordinated (

Section 4.3.1).

In this final section, we compare our research findings with some other sources on inclusive research. Several authors, including

Nind (

2011),

Dorozenko et al. (

2016), and

Tilley et al. (

2021), call for continued attention to and a critical reflection on power processes in inclusive research. In our project, Miriam was determined (after a previous rather unsuccessful collaboration with another co-researcher) not to take on a ‘carer role’ vis-à-vis her new colleague. Mark had to be a genuine colleague. Hiring a job coach for Mark clearly made a difference in this regard, as already discussed in the second paragraph of this discussion. At the same time, the findings also show that when a co-researcher has significantly less time available for the research project than the academic researcher, this has the potential to contribute to an imbalance in power. Besides this search for collegial roles, it is also noteworthy that Mark was able to learn a great deal during the various sub-studies regarding conducting interviews and analysing data. This contributed to feeling more self-confident about his research skills. Whereas in some projects, co-researchers are only or primarily involved in data collection, in this research project, the co-researcher was involved in all phases of research, as well as data analysis. Mark joined the project at a point when the data of a sub-study needed to be analysed. From the outset, he clearly contributed an experience-based perspective, but this came into a sharper focus when he was able to try out a number of methods (e.g., highlighting parts of the texts he was given). Still further, he was able to collaborate with several people from the research team for analysis (at these moments, the 1-on-1 with Miriam was opened up) and contributed his own analysis methods (a visual grouping method). It is clear that advancing insight, time, and growing research competencies all contributed to an increasingly equal power balance between the researchers. This brings us to the three approaches to inclusive research as outlined by

Bigby et al. (

2014a) and presented in our introduction. We believe we can say that, despite all the barriers, this research can for the most part be situated in the collaborative group approach (i.e., people with intellectual disabilities work in an equal partnership with academic researchers) (

Bigby et al. 2014b). Mark was given the space to realise his dream of having a job that would allow him to influence the quality of life of people with a disability. He took full advantage of the opportunity to bring the perspective of the experienced expert into the research project and to influence the progress of the research. In our opinion, there were significant attempts in this research project to take seriously the (power) balance between researchers with and without disabilities.

As a final topic of the discussion of our findings, we return to

Walmsley et al.’s (

2018) view of inclusive research. In studying the ‘second generation’ of inclusive research projects, they advocated for a special consideration for the difference that can be made by co-researchers with disabilities and for the possible impact they (also) have on the quality of life of people with disabilities. In our research project, Mark joined the team with the clear intention of making a difference for people with disabilities. We believe that, partly due to the way in which he took responsibility within the project, the DigiContact support service (being the object of the research project) was put in the picture both from the perspective of experience experts and as a realistic support option. Regarding the latter, it was shown that although DigiContact is not a miracle cure that can replace all onsite support and works equally well for everyone, it does offer people an additional support alternative that can contribute to their possibilities to participate healthily in society.

When looking back at our reflection process, we feel it would have been valuable to include more people who were also involved in or had an impact on our collaboration. For us, it was an important insight that ‘others’ played an important role in our collaboration. This was especially the case for the job coach who supported the co-researcher regarding various work-related issues and the organisation that commissioned the research project and created the conditions under which our collaboration was shaped. For this reason, it would have been interesting to involve these parties and also include their experiences and points of view. For future reflections on inclusive research processes and experiences, it is advisable to think (in advance) about which actors play a role in (or have an impact on) the collaboration and to include their voice in reflection processes as well.