Mixed-Race Ancestry ≠ Multiracial Identification: The Role Racial Discrimination, Linked Fate, and Skin Tone Have on the Racial Identification of People with Mixed-Race Ancestry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Variations among Biracials by Racial Composition

2.2. Linked Fate

2.3. Racial Discrimination

“Those guys are not thinking that way, in terms of he’s multiracial [or] he’s African… No, they’re just saying this guy has brown skin, I don’t like him. You know, and they don’t really care about what color brown skin, you know, got brown skin… if he’s not white he’s not pure, he should go back to wherever he came from. Forgetting, of course, that he came from somewhere else. No, I think racism doesn’t go for finer points” (Masuoka 2017, p. 67).

2.4. Skin Tone

2.5. Hypotheses

3. Data & Methods

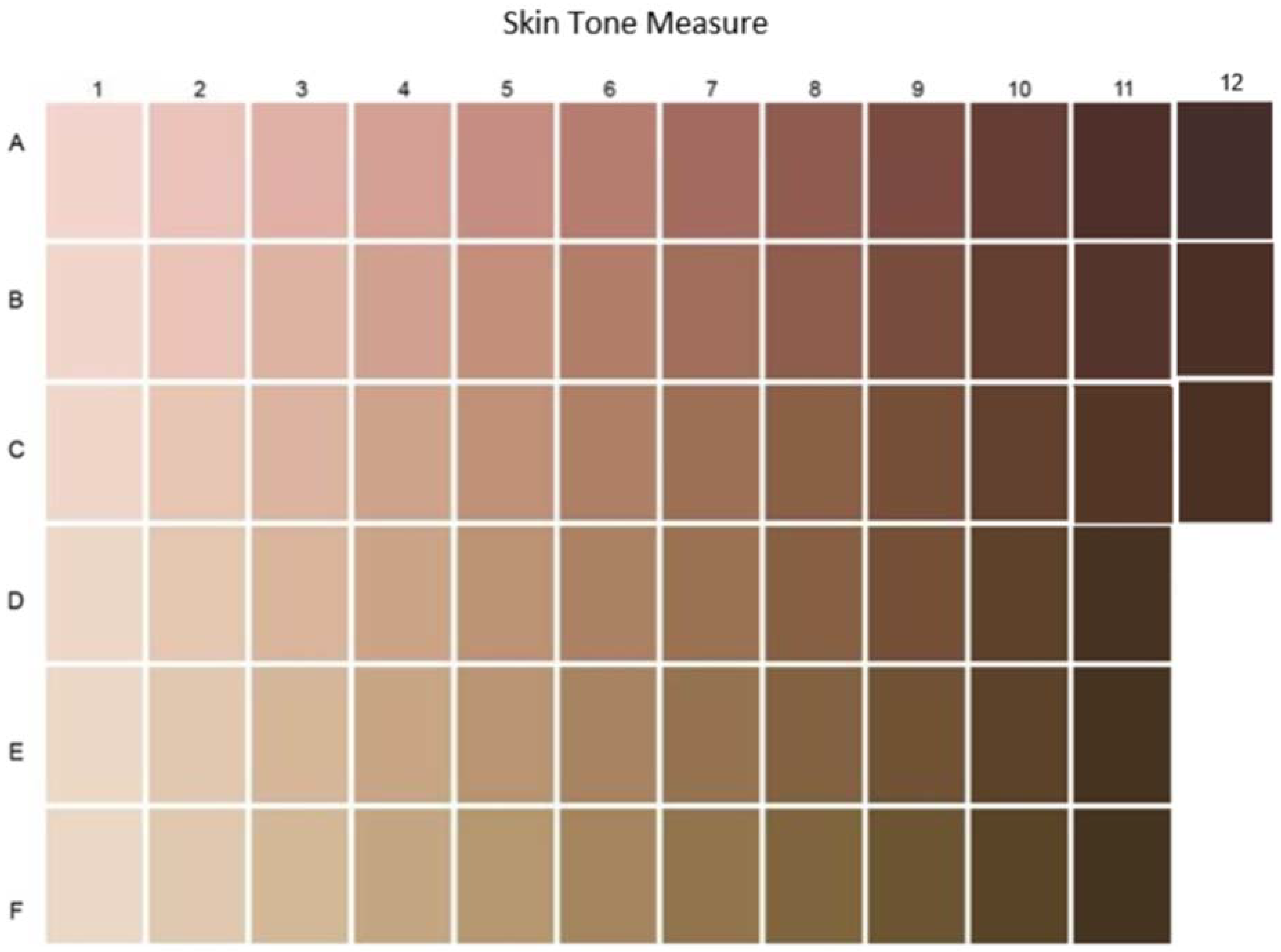

Variables

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Linked Fate on Racial Identification

4.3. Racial Discrimination on Racial Identification

4.4. Skin Tone on Racial Identification

5. Discussion

5.1. Linked Fate

5.2. Racial Discrimination

5.3. Skin Tone

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Racially Identify, in Whole or in Part, as… | Racially Identify as Multiracial (Compared to Monoracial) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black/African American | AIAN | Asian | Latinx | MENA/Arab | ||

| Treated with Less Courtesy than Others | 0.79 * | 1.84 *** | 1.08 | 1.19 | 0.76 | 0.96 | 1.07 |

| (0.08) | (0.28) | (0.10) | (0.20) | (0.11) | (0.24) | (0.08) | |

| Female (ref: male) | 1.60 | 1.89 | 0.98 | 1.16 | 0.61 | 4.04 | 1.24 |

| (0.58) | (0.78) | (0.30) | (0.51) | (0.24) | (3.44) | (0.28) | |

| TGNC (ref: male) | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.47 | 1.63 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 1.16 |

| (0.48) | (0.65) | (0.33) | (1.46) | (0.24) | (0.37) | (0.54) | |

| Age | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.80 * | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.07) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.17) | (0.05) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.54 | 1.56 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.74 |

| (0.22) | (0.69) | (0.32) | (0.44) | (0.22) | (0.46) | (0.17) | |

| Employed full time | 1.56 | 1.31 | 0.88 | 0.98 | 1.83 | 0.37 | 1.25 |

| (0.62) | (0.60) | (0.28) | (0.54) | (0.87) | (0.30) | (0.31) | |

| Annual income $45,000–$75,000 (ref: $45,000 or less) | 0.67 | 1.44 | 1.43 | 1.67 | 1.11 | 0.64 | 1.08 |

| (0.28) | (0.78) | (0.50) | (0.89) | (0.58) | (0.57) | (0.28) | |

| Annual income $75,001 or greater (ref: $45,000 or less) | 1.18 | 0.80 | 1.80 | 1.62 | 1.04 | 1.65 | 2.08 * |

| (0.56) | (0.40) | (0.69) | (1.05) | (0.56) | (1.60) | (0.62) | |

| Southeast | 0.46 * | 0.87 | 0.96 | 1.67 | 0.85 | 0.31 | 0.59 * |

| (0.16) | (0.41) | (0.32) | (1.22) | (0.36) | (0.27) | (0.14) | |

| Skin tone (5-point scale) | 0.80 | 2.56 *** | 0.96 | 0.83 | 1.71 * | 1.58 | 1.31 * |

| (0.15) | (0.53) | (0.15) | (0.18) | (0.42) | (0.73) | (0.16) | |

| Observations | 369 | 187 | 215 | 185 | 162 | 50 | 514 |

| 1 | I use quotation marks around “choices” to emphasize that many individuals with mixed ancestry feel their racial identity is not something they choose, but rather an identity that is expected of them or that they are treated as (Khanna 2010). Many other individuals with mixed ancestry feel that they do have multiple identification options available (Rockquemore and Arend 2002), and still others report racial identities that vary over time (Doyle and Kao 2007). |

| 2 | Racial identification is also known as “self-classification” (Roth 2016), “expressed race” (Roth 2010), “expressed internal race” (Harris and Sim 2002), and “self-reported race” (Saperstein 2006). |

| 3 | While I use “Latinx” throughout my writing to be inclusive of all genders, in this survey I use “Latina/o/x” in order to be clear to both academic and nonacademic respondents. |

| 4 | By cell I mean the subgroup within a subpopulation. For example, Black/Asians are a subgroup of multiracials. |

| 5 | To clarify how these racial identifications were determined: all respondents were first asked about their racial ancestry and later asked about their own racial identification. If, for example, someone with Black ancestry identified as Black alone or in part, they were recorded in the Black category. If someone with Black ancestry selected multiple racial groups to describe their racial identification, they were put in the multiracial category. Thus, one respondent may be in both the “mono- or multiracial Black” group and also in the “multiracial” group. A respondent may also be represented only in the “mono- or multiracial Black” group and not in the “multiracial” group. |

References

- Ahnallen, Julie M., Karen L. Suyemoto, and Alice S. Carter. 2006. Relationship between Physical Appearance, Sense of Belonging and Exclusion, and Racial/Ethnic Self-Identification among Multiracial Japanese European Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 12: 673–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anson, Ian G. 2018. Taking the Time? Explaining Effortful Participation among Low-Cost Online Survey Participants. Research & Politics 5: 2053168018785483. [Google Scholar]

- Bakalian, Anny, and Mehdi Bozorgmehr. 2011. Middle Eastern and Muslim American Studies Since 9⁄11. In Sociological Forum. Hoboken: Wiley, vol. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Derrick. 1992. Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun, Khaled A. 2013. Between Muslim and White: The Legal Construction of Arab American Identity. New York University Annual Survey of American Law 69: 29. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2004. From Bi-Racial to Tri-Racial: Towards A New System of Racial Stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies 27: 931–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsma, David. 2006. Public Categories, Private Identities: Exploring Regional Differences in the Biracial Experience. Social Science Research 35: 555–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsma, David L., and Kerry Ann Rockquemore. 2001. The New Color Complex: Appearances and Biracial Identity. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 1: 225–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buggs, Shantel Gabrieal. 2019. Color, Culture, or Cousin? Multiracial Americans and Framing Boundaries in Interracial Relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family 81: 1221–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Mary E., Verna M. Keith, Vanessa Gonlin, and Adrienne R. Carter-Sowell. 2020. Is A Picture Worth A Thousand Words? An Experiment Comparing Observer-Based Skin Tone Measures. Race and Social Problems 12: 266–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, Deborah Faye, and Sylvia Hurtado. 2007. Bridging Key Research Dilemmas: Quantitative Research Using a Critical Eye. In New Directions for Institutional Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Casler, Krista, Lydia Bickel, and Elizabeth Hackett. 2013. Separate but Equal? A Comparison of Participants and Data Gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, Social Media, and Face-to-Face Behavioral. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 2156–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Dennis, and Reuel Rogers. 2005. Racial Solidarity and Political Participation. Political Behavior 27: 347–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, Maureen A., and Jennifer A. Richeson. 2016. Stigma-Based Solidarity: Understanding the Psychological Foundations of Conflict and Coalition Among Members of Different Stigmatized Groups. Current Directions in Psychological Science 25: 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Castillo, Richard Griswold. 1992. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo: A Legacy of Conflict. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colby, Sandra L., and Jennifer M. Ortman. 2015. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Lauren D. 2018. Politics beyond Black & White: Biracial Identity and Attitudes in America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, Lauren D., Shanto Iyengar, and Sean J. Westwood. 2021. Racial Identity, Group Consciousness, and Attitudes: A Framework for Assessing Multiracial Self-Classification. American Journal of Political Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, Lauren, Annie Franco, and Shanto Iyengar. 2022. Multiracial Identity and Political Preferences. Journal of Politics 84: 620–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Floyd James. 1991. Who Is Black? One Nation’s Definition. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Michael C. 1994. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic. 2017. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 3rd ed. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, Julie A. 2015. Mexican Americans and the Questions of Race. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Jamie Mihoko, and Grace Kao. 2007. Are Racial Identities of Multiracials Stable? Changing Self-Identification among Single and Multiple Race Individuals. Social Psychology Quarterly 70: 405–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. 2015. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Espino, Rodolfo, and Michael M. Franz. 2002. Latino Phenotypic Discrimination Revisited: The Impact of Skin Color on Occupational Status. Social Science Quarterly 83: 612–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essed, Philomena. 1991. Understanding Everyday Racism: An Interdisciplinary Theory, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner, Samuel L., and John F. Dovidio. 2000. Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Common Ingroup Identity Model. Philadelphia: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, Nichole M., Nancy López, and Verónica N. Vélez. 2018. QuantCrit: Rectifying Quantitative Methods through Critical Race Theory. Race Ethnicity and Education 21: 149–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, Claudine. 2004. Putting Race in Context: Identifying the Environmental Determinants of Black Racial Attitudes. American Political Science Review 98: 547–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gay, Claudine, and Katherine Tate. 1998. Doubly Bound: The Impact of Gender and Race on the Politics of Black Women. Political Psychology 19: 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, Claudine, Jennifer L. Hochschild, and Ariel White. 2016. Americans’ Belief in Linked Fate: Does the Measure Capture the Concept? Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Politics 1: 117–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giamo, Lisa S., Michael T. Schmitt, and H. Robert Outten. 2012. Perceived Discrimination, Group Identification, and Life Satisfaction among Multiracial People: A Test of the Rejection-Identification Model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 18: 319–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golash-Boza, Tanya, and William Darity Jr. 2008. Latino Racial Choices: The Effects of Skin Colour and Discrimination on Latinos’ and Latinas’ Racial Self-Identifications. Ethnic and Racial Studies 31: 899–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Fang, Jun Xu, and David T. Takeuchi. 2017. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Perceptions of Everyday Discrimination. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 3: 506–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonlin, Vanessa. 2019. Mixed-Race Ancestry Survey. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Gonlin, Vanessa, Nicole E. Jones, and Mary E. Campbell. 2020. On the (Racial) Border: Expressed Race, Reflected Race, and the U.S.-Mexico Border Context. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 6: 161–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Backen, Melinda A., and Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor. 2011. Examining the Role of Physical Appearance in Latino Adolescents’ Ethnic Identity. Journal of Adolescence 34: 151–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, Zareena A. 2009. Marriage in Colour: Race, Religion and Spouse Selection in Four American Mosques. Ethnic and Racial Studies 32: 323–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullickson, Aaron, and Ann Morning. 2011. Choosing Race: Multiracial Ancestry and Identification. Social Science Research 40: 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, David R., and Jeremiah J. Sim. 2002. Who Is Multiracial? Assessing the Complexity of Lived Race. American Sociological Review 67: 614–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Jessica C. 2016. Toward a Critical Multiracial Theory in Education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 29: 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebl, Michelle R., Melissa J. Williams, Jane M. Sundermann, Harrison J. Kell, and Paul G. Davies. 2012. Selectively Friending: Racial Stereotypicality and Social Rejection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48: 1329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Melissa R. 2004. Forced to Choose: Some Determinants of Racial Identification in Multiracial Adolescents. Child Development 75: 730–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Sonia. 2001. The Legacy of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on Tejanos’ Land. The Journal of Popular Culture 35: 101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, Cedric, Verna Keith, and Hayward Derrick Horton, eds. 2004. Skin Deep: How Race and Complexion Matter in the “Color-Blind” Era. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hersch, Joni. 2006. Skin-Tone Effects among African Americans: Perceptions and Reality. The American Economic Review 96: 251–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hersch, Joni. 2008. Profiling the New Immigrant Worker: Effects of Skin Color and Height. Journal of Labor Economics 26: 345–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Jennifer L., and Vesla M. Weaver. 2007. The Skin Color Paradox and the American Racial Order. Social Forces 86: 643–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, Margaret L. 2007. The Persistent Problem of Colorism: Skin Tone, Status, and Inequality. Sociology Compass 1: 237–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, Gerald David, and Robin M. Williams Jr., eds. 1989. A Common Destiny: Blacks in American Society. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Correa, Michael. 2011. Commonalities, Competition and Linked Fate. In Just Neighbors?: Research on African American and Latino Relations in the United States. Edited by Edward Telles, Mark Sawyer and Gaspar Rivera-Salgado. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Nicholas A., and Jungmiwha Bullock. 2012. The Two or More Races Population: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, Nikki. 2004. The Role of Reflected Appraisals in Racial Identity: The Case of Multiracial Asians. Social Psychology Quarterly 67: 115–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, Nikki. 2010. “If You’re Half Black, You’re Just Black” Reflected Appraisals at the Persistence of the One-Drop Rule. Sociological Quarterly 51: 380–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, Nikki. 2011. ‘I’m Not Like Them At All’: Social Comparisons and Social Networks. In Biracial in America: Forming and Performing Racial Identity. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Giyeon, Martin Sellbom, and Katy-Lauren Ford. 2014. Race/Ethnicity and Measurement Equivalence of the Everyday Discrimination Scale. Psychological Assessment 26: 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klonoff, Elizabeth A., and Hope Landrine. 2000. Is Skin Color a Marker for Racial Discrimination? Explaining the Skin Color–Hypertension Relationship. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 23: 329–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebler, Carolyn. 2016. On the Boundaries of Race: Identification of Mixed-Heritage Children in the United States, 1960 to 2010. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2: 548–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebler, Carolyn A., and Andrew Halpern-Manners. 2008. A Practical Approach to Using Multiple-Race Response Data: A Bridging Methodology for Public Use Microdata. Demography 45: 143–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, Jennifer, and Frank D. Bean. 2004. America’s Changing Color Lines: Immigration, Race/Ethnicity, and Multiracial Identification. Annual Review of Sociology 30: 221–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, Nancy, Edward Vargas, Melina Juarez, Lisa Cacari-Stone, and Sonia Bettez. 2018. What’s Your ‘Street Race’? Leveraging Multidimensional Measures of Race and Intersectionality for Examining Physical and Mental Health Status among Latinxs. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 4: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, Fan, and Bradford Jones. 2019. Effects of Belief versus Experiential Discrimination on Race-Based Linked Fate. Politics, Groups, and Identities 7: 615–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghbouleh, Neda. 2020. From White to What? MENA and Iranian American Non-White Reflected Race. Ethnic and Racial Studies 43: 613–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuoka, Natalie. 2006. Together They Become One: Examining the Predictors of Panethnic Group Consciousness among Asian Americans and Latinos. Social Science Quarterly 87: 993–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuoka, Natalie. 2017. Multiracial Identity and Racial Politics in the United States. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McConnaughy, Corrine M., Ismail K. White, David L. Leal, and Jason P. Casellas. 2010. A Latino on the Ballot: Explaining Coethnic Voting among Latinos and the Response of White Americans. The Journal of Politics 72: 1199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mills, Melinda. 2017. The Borders of Race: Patrolling “Multiracial” Identities. Boulder: First Forum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki, Michael H. 2015. Expanding Boundaries of Whiteness? A Look at the Marital Patterns of Part-White Multiracial Groups. Sociological Forum 30: 995–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, Ellis P. 2014. Skin Tone Stratification among Black Americans, 2001–2003. Social Forces 92: 1313–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, Ellis P. 2015. The Cost of Color: Skin Color, Discrimination, and Health among African-Americans. American Journal of Sociology 121: 396–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morning, Ann. 2000. Who Is Multiracial? Definitions and Decisions. Sociological Imagination 37: 209–29. [Google Scholar]

- Morning, Ann. 2018. Kaleidoscope: Contested Identities and New Forms of Race Membership. Ethnic and Racial Studies 41: 1055–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, Heather A., Jenifer L. Bratter, and Raul S. Casarez. 2020. One Drop on the Move: Historical Legal Context, Racial Classification, and Migration. Ethnic and Racial Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauker, Kristin, Chanel Meyers, Diana T. Sanchez, Sarah E. Gaither, and Danielle M. Young. 2018. A Review of Multiracial Malleability: Identity, Categorization, and Shifting Racial Attitudes. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 12: e12392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2015. Multiracial in America: Proud, Diverse and Growing in Numbers. Multiracial in America. Available online: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/multiracial-in-america/st_2015-06-11_multiracial-americans_00-06/ (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Quiros, Laura, and Beverly Araujo Dawson. 2013. The Color Paradigm: The Impact of Colorism on the Racial Identity and Identification of Latinas. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 23: 287–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockquemore, Kerry Ann, and David L. Brunsma. 2001. Beyond Black: Biracial Identity in America, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rockquemore, Kerry Ann, and David L. Brunsma. 2004. The Reflexivity of Appearances in Racial Identification among Black/White Biracials. In Skin Deep: How Race and Complexion Matter in the “Color-Blind” Era. Edited by Cedric Herring, Verna M. Keith and Hayward Derrick Horton. Chicago, Urbana and Champaign: University of Illinois Press, pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rockquemore, Kerry Ann, and David L. Brunsma. 2008. Negotiating Racial Identity: Biracial Women and Interactional Validation. Women & Therapy 27: 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rockquemore, Kerry Ann, and Patricia Arend. 2002. Opting for White: Choice, Fluidity and Racial Identity Construction in Post Civil-Rights America. Race and Society 5: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roediger, David. 2005. Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White; The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Rondilla, Joanne L., and Paul Spickard. 2007. Is Lighter Better?: Skin-Tone Discrimination Among Asian Americans. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Root, Maria P. 1990. Resolving ‘Other’ Status: Identity Development of Biracial Individuals. Women & Therapy 9: 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Wendy D. 2010. Racial Mismatch: The Divergence Between Form and Function in Data for Monitoring Racial Discrimination of Hispanics. Social Science Quarterly 91: 1288–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, Wendy D. 2016. The Multiple Dimensions of Race. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 1310–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanchez, Gabriel R., and Edward D. Vargas. 2016. Taking a Closer Look at Group Identity: The Link between Theory and Measurement of Group Consciousness and Linked Fate. Political Research Quarterly 69: 160–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saperstein, Aliya. 2006. Double-Checking the Race Box: Examining Inconsistency between Survey Measures of Observed and Self-Reported Race. Social Forces 85: 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saperstein, Aliya, and Andrew M. Penner. 2012. Racial Fluidity and Inequality in the United States. American Journal of Sociology 118: 676–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkraut, Deborah J. 2017. White Attitudes about Descriptive Representation in the US: The Roles of Identity, Discrimination, and Linked Fate. Politics, Groups, and Identities 5: 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, Robert M., Stephanie A. J. Rowley, Tabbye M. Chavous, J. Nicole Shelton, and Mia A. Smith. 1997. Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A Preliminary Investigation of Reliability and Constuct Validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73: 805–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, Robert M., and J. Nicole Shelton. 2003. The Role of Racial Identity in Perceived Racial Discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84: 1079–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, Robert M., Mia A. Smith, J. Nicole Shelton, Stephanie A. J. Rowley, and Tabbye M. Chavous. 1998. Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A Reconceptualization of African American Racial Identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2: 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shelby, Tommie. 2005. We Who Are Dark: The Philosophical Foundations of Black Solidarity. Cambridge: Harvard Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simien, Evelyn M. 2005. Race, Gender, and Linked Fate. Journal of Black Studies 35: 529–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, Dionne P., and Paula Fernández. 2012. The Role of Skin Color on Hispanic Women’s Perceptions of Attractiveness. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 34: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Farrell, and Vanessa Gonlin. 2019. Questions and Concerns Regarding Family Theories: Biracial and Multiracial Family Issues. In Biracial Families: Crossing Boundaries, Blending Cultures, and Challenging Racial Ideologies. Edited by Roudi Roy and Alethea Rollins. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Betina Cutaia. 2014. Perceptions of Commonality and Latino-Black, Latino-White Relations in a Multiethnic United States. Political Research Quarterly 67: 905–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, David R., Yan Yu, James S. Jackson, and Norman Anderson. 1997. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socio-Economic Status, Stress and Discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology 2: 335–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wong, Janelle S., Pei-Te Lien, and M. Margaret Conway. 2005. Group-Based Resources and Political Participation among Asian Americans. American Politics Research 33: 545–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Percentage | N | |

|---|---|---|

| Racial Ancestry Includes… | ||

| White | 71.7 | 369 |

| Black/African American | 36.3 | 187 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 41.9 | 216 |

| Asian | 36.1 | 186 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 6.4 | 33 |

| Hispanic or Latina/o/x | 31.5 | 162 |

| Middle Eastern/North African | 9.7 | 50 |

| Multiple Racial Ancestries (N of 10+) | ||

| White/AIAN | 13.4 | 69 |

| White/Asian | 12.8 | 66 |

| White/Black | 8.5 | 44 |

| White/Latinx | 13.0 | 67 |

| White/MENA | 2.7 | 14 |

| Black/AIAN | 3.1 | 16 |

| Black/Latinx | 3.9 | 20 |

| Black/MENA | 2.3 | 12 |

| AIAN/Asian | 9.1 | 47 |

| White/Black/AIAN | 4.5 | 23 |

| White/Black/Latinx | 2.3 | 12 |

| White/AIAN/Latinx | 1.9 | 10 |

| Gender identity | ||

| Male | 46.8 | 241 |

| Female | 46.2 | 238 |

| Transgender male/transgender man | 4.9 | 25 |

| Transgender female/transgender woman | 0.4 | 2 |

| Non-binary | 0.8 | 4 |

| Genderqueer/gender-nonconforming | 0.6 | 3 |

| Other ____ | 0.4 | 2 |

| Pronouns | ||

| He/him | 46.4 | 239 |

| She/her | 46.2 | 238 |

| They/them | 4.5 | 23 |

| Other ____ | 2.9 | 15 |

| Age category | ||

| 18–29 | 55.9 | 288 |

| 30–39 | 24.9 | 128 |

| 40–49 | 9.5 | 49 |

| 50–59 | 7.0 | 36 |

| 60–69 | 2.1 | 11 |

| 70+ | 0.6 | 3 |

| Education | ||

| Elementary school to some high school | 1.2 | 6 |

| High school diploma or GED | 10.1 | 52 |

| Vocational school | 2.3 | 12 |

| Some college | 17.1 | 88 |

| Associate’s degree | 8.5 | 44 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 41.8 | 215 |

| Master’s or doctorate’s degree | 19.0 | 98 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed full time | 69.9 | 360 |

| Employed part time | 15.7 | 81 |

| Not working, retired, homemaker, or student not working | 14.4 | 74 |

| Household income | ||

| $10,000 or less | 5.6 | 29 |

| $10,001–$20,000 | 10.5 | 54 |

| $20,001–$30,000 | 16.1 | 83 |

| $30,001–$45,000 | 18.6 | 96 |

| $45,001–$60,000 | 13.6 | 70 |

| $60,001–$75,000 | 11.8 | 61 |

| $75,001–$100,000 | 15.2 | 78 |

| $100,001–$250,000 | 7.6 | 39 |

| $250,001+ | 1.0 | 5 |

| Geography | ||

| Northeast | 11.5 | 59 |

| Southeast | 24.7 | 127 |

| Southwest | 14.8 | 76 |

| Midwest | 23.1 | 119 |

| West | 25.1 | 129 |

| U.S. Islands and Territories | 0.8 | 4 |

| Skin Tone Measure (5-point scale) | ||

| Very light | 45.2 | 233 |

| Light | 28.4 | 146 |

| Medium | 18.8 | 97 |

| Dark | 4.7 | 24 |

| Very dark | 2.9 | 15 |

| Data: Mixed-Race Ancestry Survey, 2019 |

| Racially Identify, in Whole or in Part, as… | Racially Identify as Multiracial (Compared to Monoracial) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black/African American | AIAN | Asian | Latinx | MENA/Arab | ||

| Linked fate with respective group | 1.52 ** | 2.15 *** | 1.60 ** | 1.82 ** | 1.58 * | 1.79 | 1.37 ** |

| (0.23) | (0.38) | (0.23) | (0.38) | (0.30) | (0.62) | (0.13) | |

| Female (ref: male) | 1.35 | 1.83 | 0.98 | 1.18 | 0.66 | 2.84 | 1.08 |

| (0.51) | (0.78) | (0.31) | (0.54) | (0.27) | (2.27) | (0.25) | |

| TGNC (ref: male) | 0.36 | 1.34 | 0.35 | 1.75 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 1.05 |

| (0.24) | (1.32) | (0.23) | (1.50) | (0.21) | (0.22) | (0.49) | |

| Age | 0.91 | 0.90 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| (0.06) | (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.08) | (0.17) | (0.05) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.48 | 1.77 | 1.01 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.73 |

| (0.19) | (0.82) | (0.31) | (0.52) | (0.21) | (0.39) | (0.18) | |

| Employed full time | 1.38 | 1.87 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 1.35 | 0.41 | 1.27 |

| (0.55) | (0.81) | (0.29) | (0.49) | (0.64) | (0.31) | (0.31) | |

| Annual income $45,000–$75,000 (ref: $45,000 or less) | 0.86 | 0.97 | 1.27 | 1.70 | 1.40 | 0.45 | 1.10 |

| (0.37) | (0.54) | (0.45) | (0.93) | (0.72) | (0.50) | (0.29) | |

| Annual income $75,001 or greater (ref: $45,000 or less) | 1.49 | 0.59 | 1.89 | 1.59 | 1.09 | 1.38 | 2.07 * |

| (0.68) | (0.30) | (0.76) | (0.99) | (0.57) | (1.33) | (0.64) | |

| Southeast | 0.44 * | 1.09 | 0.90 | 1.50 | 0.91 | 0.41 | 0.58 * |

| (0.16) | (0.50) | (0.30) | (1.23) | (0.40) | (0.36) | (0.14) | |

| Skin tone (4-point scale) | 0.77 | 1.94 *** | 0.92 | 0.81 | 1.48 | 1.31 | 1.24 |

| (0.14) | (0.37) | (0.15) | (0.17) | (0.41) | (0.61) | (0.16) | |

| Observations | 368 | 186 | 216 | 184 | 160 | 50 | 510 |

| Racially Identify, in Whole or in Part, as… | Racially Identify as Multiracial (Compared to Monoracial) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black/African American | AIAN | Asian | Latinx | MENA/Arab | ||

| Everyday Discrimination Scale | 0.96 ** | 1.07 ** | 1.02 | 1.03 | 0.96 * | 0.97 | 1.01 |

| (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.01) | |

| Female (ref: male) | 1.46 | 2.12 | 0.91 | 1.18 | 0.57 | 4.54 | 1.16 |

| (0.55) | (0.89) | (0.29) | (0.52) | (0.24) | (4.22) | (0.27) | |

| TGNC (ref: male) | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.45 | 1.45 | 0.27 | 0.48 | 1.05 |

| (0.65) | (0.72) | (0.33) | (1.33) | (0.31) | (0.71) | (0.50) | |

| Age | 0.93 | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.09) | (0.09) | (0.16) | (0.05) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.56 | 1.46 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.51 | 0.66 | 0.73 |

| (0.24) | (0.65) | (0.32) | (0.43) | (0.24) | (0.48) | (0.17) | |

| Employed full time | 1.72 | 1.18 | 0.81 | 0.93 | 1.91 | 0.36 | 1.21 |

| (0.72) | (0.56) | (0.27) | (0.51) | (0.92) | (0.28) | (0.31) | |

| Annual income $45,000–$75,000 (ref: $45,000 or less) | 0.62 | 1.47 | 1.46 | 1.82 | 1.14 | 0.68 | 1.13 |

| (0.27) | (0.80) | (0.53) | (1.03) | (0.59) | (0.63) | (0.30) | |

| Annual income $75,001 or greater (ref: $45,000 or less) | 0.96 | 0.89 | 1.90 | 1.74 | 1.10 | 1.78 | 2.05 * |

| (0.47) | (0.45) | (0.76) | (1.14) | (0.62) | (1.69) | (0.61) | |

| Southeast | 0.47 * | 0.88 | 0.99 | 1.68 | 0.86 | 0.31 | 0.61 * |

| (0.17) | (0.42) | (0.33) | (1.21) | (0.37) | (0.29) | (0.15) | |

| Skin tone (4-point scale) | 0.83 | 2.74 *** | 0.94 | 0.87 | 1.57 | 1.77 | 1.30 * |

| (0.15) | (0.58) | (0.15) | (0.19) | (0.40) | (0.88) | (0.17) | |

| Observations | 351 | 175 | 203 | 176 | 157 | 48 | 488 |

| Racially Identify, in Whole or in Part, as… | Racially Identify as Multiracial (Compared to Monoracial) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black/African American | AIAN | Asian | Latinx | MENA/Arab | ||

| Skin tone (4-point scale) | 0.76 | 3.03 *** | 0.97 | 0.88 | 1.31 | 1.56 | 1.29 * |

| (0.14) | (0.61) | (0.16) | (0.19) | (0.36) | (0.74) | (0.16) | |

| Female (ref: male) | 1.28 | 1.88 | 0.92 | 1.11 | 0.63 | 3.61 | 1.09 |

| (0.49) | (0.80) | (0.29) | (0.50) | (0.27) | (2.78) | (0.26) | |

| TGNC (ref: male) | 0.41 | 1.12 | 0.47 | 1.53 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.98 |

| (0.27) | (1.02) | (0.34) | (1.45) | (0.25) | (0.44) | (0.47) | |

| Age | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.80 * | 0.99 | 0.95 | 0.92 |

| (0.07) | (0.10) | (0.07) | (0.08) | (0.10) | (0.18) | (0.05) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 0.57 | 1.71 | 1.03 | 0.92 | 0.45 | 0.60 | 0.75 |

| (0.23) | (0.79) | (0.33) | (0.47) | (0.23) | (0.45) | (0.19) | |

| Employed full time | 1.29 | 1.92 | 0.91 | 1.04 | 1.47 | 0.37 | 1.34 |

| (0.53) | (0.87) | (0.30) | (0.56) | (0.72) | (0.29) | (0.34) | |

| Annual income $45,000–$75,000 (ref: $45,000 or less) | 0.75 | 1.19 | 1.34 | 1.35 | 1.57 | 0.67 | 1.11 |

| (0.33) | (0.61) | (0.49) | (0.71) | (0.88) | (0.62) | (0.30) | |

| Annual income $75,001 or greater (ref: $45,000 or less) | 1.03 | 0.94 | 1.74 | 1.38 | 1.08 | 1.54 | 2.02 * |

| (0.49) | (0.50) | (0.69) | (0.88) | (0.64) | (1.46) | (0.63) | |

| Southeast | 0.49 * | 1.08 | 0.99 | 1.68 | 0.87 | 0.32 | 0.65 |

| (0.17) | (0.52) | (0.33) | (1.26) | (0.38) | (0.28) | (0.16) | |

| Observations | 333 | 166 | 198 | 165 | 146 | 48 | 464 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonlin, V. Mixed-Race Ancestry ≠ Multiracial Identification: The Role Racial Discrimination, Linked Fate, and Skin Tone Have on the Racial Identification of People with Mixed-Race Ancestry. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040160

Gonlin V. Mixed-Race Ancestry ≠ Multiracial Identification: The Role Racial Discrimination, Linked Fate, and Skin Tone Have on the Racial Identification of People with Mixed-Race Ancestry. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(4):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040160

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonlin, Vanessa. 2022. "Mixed-Race Ancestry ≠ Multiracial Identification: The Role Racial Discrimination, Linked Fate, and Skin Tone Have on the Racial Identification of People with Mixed-Race Ancestry" Social Sciences 11, no. 4: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040160

APA StyleGonlin, V. (2022). Mixed-Race Ancestry ≠ Multiracial Identification: The Role Racial Discrimination, Linked Fate, and Skin Tone Have on the Racial Identification of People with Mixed-Race Ancestry. Social Sciences, 11(4), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040160