Abstract

The main objective of this study was to analyze the mediating effect of perceived employability (internal and external) and the organizational commitment in the relationship between the organizational practices of competencies development (OPCD) and the turnover intentions. The sample consists of 2099 participants, all of them working in organizations based in Portuguese territory. The existence of a significant and negative effect of the OPCD, of perceived internal employability and the organizational commitment in the turnover intentions, has been proven. There was also a significant and positive effect of perceived external employability on turnover intentions. Finally, the serial mediating effect of perceived employability and organizational commitment in the relationship between OPCD and turnover intentions was proven.

1. Introduction

We live in a time where the work environment is constantly changing, both at the level of organizations and employees. In this scenario, one of the main problems organizations face is the high turnover of employees, which brings losses to the organization, especially regarding highly qualified employees (Rahman and Nas 2013; Reiche 2008). It is, therefore, necessary to retain the best employees since they are the essential source for the organization to obtain a sustainable competitive advantage (Pfeffer 1996).

According to the “resource-based view” theory, the organization can determine its strategic resources and use them correctly, which will become strategically important for its success (Barney 1991).

To retain these employees, they must strive to create a culture where their competencies development programs are highly encouraged (Malik et al. 2011). This investment is associated with social exchange relationships that build feelings of obligation on the part of the employee towards the organization (Shore et al. 2006). Based on this perspective, it is considered that the impact of these practices’ perception on the attitudes and employees’ behaviour is significantly based on the premise of social exchanges (Blau 1964) and the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner 1960).

If the employee feels that the organization invests in the development of their competencies, he will have a higher perception of employability (Wittekind et al. 2010), which will lead to developing a higher commitment (affective and normative) to the organization, reducing turnover intentions (Meyer 2014).

This study has two objectives. The first objective is to study the effect of the organizational practices of competencies development (OPCDs), perceived employability (internal and external), and organizational commitment (affective and normative) on turnover intentions. The second objective is to analyze whether the perceived employability (internal and external) and the organizational commitment (affective and normative) explain the relationship between the OPCD and the turnover intentions. The purpose of this study is to provide organizations with additional guidance on how to retain the best employees by developing their competencies.

1.1. Organizational Practices of Competencies Development and Turnover Intentions

One of the crucial aspects for an organization to achieve and maintain a competitive advantage in the current environment of constant change is to invest in implementing practices to develop the competencies of its employees (Heffernan and Flood 2000). The competencies development can be considered a strategic tool for Human Resources Management to deal with the labour market (Nyhan 1998). It can improve the organization’s effectiveness the quality of its products or services make it innovative and able to respond quickly and appropriately to the customer, reducing costs creating value and profit (Hill and Jones 2004).

Fleury and Fleury (2000) defines competence as knowing how to act responsibly, which implies mobilizing, integrating, transferring knowledge, resources, competencies, which adds economic value to the organization and social value to the employee. Still in this line, Lee and Bruvold (2003) considers this investment in developing employees’ competencies as a fundamental principle to develop as a whole, both the competencies of employees and the organization. According to the Human Capital Theory (Schultz 1961), when an organization can implement practices that promote the competencies of its employees, it is creating means (human capital) that differentiate it from others, making it more competitive.

As for OPCD, De Vos and De Hauw (2009) define them as all the activities carried out by the organization and the employee, whose purpose is to maintain or improve the functional performance, learning, and competencies same. The existing competencies development methodologies are diverse. In this study, we will focus on the model proposed by De Vos et al. (2011), where these authors identify three different methods to be adopted by organizations: training, functional rotation, and individualized support. This model of competencies development is in line with other authors, who consider that this development can be accomplished through various means such as training, coaching, and mentoring (Asiegbu et al. 2011; Grant et al. 2009). According to De Vos et al. (2011), training can be divided into formal or informal. Formal training refers to the training promoted by the organization, while informal training (on-the-job training) is where the worker learns with the support of more experienced colleagues who guide their work. The functional rotation includes the chance that the employee has to perform other functions within the organization through the opportunity to compete for internal vacancies. As for individualized support, this includes support from your direct manager or from a senior member designated by the organization (mentoring) concerning career development, as well as coaching programs, which are designed to develop employee-oriented competencies objectives, to improve not only their performance but their quality of life within the organization (Brock 2006).

The development of employees’ competencies has become crucial in organizations, and they should invest in practices that target them, leading them to express lesser turnover intentions (Benson 2006; Kim 2005; Rahman and Nas 2013). Turnover intentions are understood as the desire that employees have to leave the organization and look for another job (Benson 2006). When an employee realizes that the organization cares about him, promoting the development of his competencies, it is natural not to express turnover intentions (Eisenberger et al. 2001), wanting to repay all the investment made, which can be interpreted based on the premise of social exchanges (Blau 1964) and the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner 1960). Another theory that we can rely on to explain this relationship is the Theory of Social Comparison (Adams 1965) because this author tells us that employees tend to compare the organization they work with others and, if they perceive that yours provides them with better competencies development, they will certainly stay there.

Several empirical studies focus on the relationship between competencies development programs and turnover intentions, pointing to a significant and negative relationship between these two constructs. In a study with employees from the banking sector, developed by Malik et al. (2011), the conclusion was that investment in employee competencies development is associated with lower intentions to leave the organization. In addition, the study carried out by Rahman and Nas (2013) goes in the same direction.

In this sense, the first hypothesis of this study was formulated:

Hypothesis 1.

The perception of OPCD (training, individualized support, and functional rotation) has a significant and negative effect on turnover intentions.

Perceived Employability (Internal and External) and Turnover Intentions

In an era of globalization, in which the labour market is characterized by flexibility and uncertainty, perceived employability has become crucial, as it can reduce, the fear of becoming unemployed, since perceived employability makes employees feel less vulnerable (Berntson et al. 2007; Berntson and Marklund 2007) and hope to find a new job, either in your organization or another, if needed.

According to De Witte (2005), perceived employability has two distinct dimensions: perceived internal employability and perceived external employability. Perceived internal employability refers to a worker’s ability to feel that they have career opportunities in their current job, once their professional competencies facilitate internal rotation or mobility, the application of his potential is managed appropriately, feeling that he has value to the organization where he works. A high perception of internal employability means that employees are more likely to keep their current job (De Witte 2005). Perceived external employability refers to the employee’s perceived value in the labour market and how high the probability of finding another job in another organization gives him better prospects for professional development or higher levels of compensation and benefits and may generate self-confidence because he knows that in the face of an unexpected situation of breaking the link, he can easily find another job (De Cuyper and De Witte 2011). As for the relationship between perceived internal employability and turnover intentions, this can be interpreted based on the theory of resource conservation (Hobfoll 1989), since perceived internal employability can be considered a resource. When a collaborator has a high perception of internal employability, he will certainly not want to lose this resource, which will cause his turnover intentions to decrease (Acikgoz et al. 2016; De Cuyper et al. 2012). De Cuyper et al. (2011) hypothesized a significant and negative association between perceived internal employability and turnover intentions and a significant and positive relationship between perceived external employability and turnover intentions. However, they were unable to prove their hypotheses, suggesting the existence of mediators or moderators in these relationships. Other studies, including those carried out by Sánchez-Manjavacas et al. (2014) Usmani (2016), sought to establish these relationships without obtaining significant results. In line with the hypothesis tested by De Cuyper et al. (2011), the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 2.

Perceived internal employability has a significant and negative effect on turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 3.

Perceived external employability has a significant and positive effect on turnover intentions.

1.2. Organizational Commitment (Affective and Normative) and Turnover Intentions

Meyer and Allen (1991), defines organizational commitment as a psychological state that links an employee to the organization, making turnover intentions less desirable. Ng (2015) considers that this psychological link is a stabilizing force that links employees to organizations. The three-component model of Meyer and Allen (1991) distinguishes between three types of commitment: affective commitment, calculative commitment, and normative commitment. In this study, we will only look at affective and normative commitment.

Affective commitment is interpreted as the emotional connection, identification and involvement of the employee with the organization where he works (Meyer and Allen 1984), believing that it is the result of an exchange between the organization and the employee (Colquitt et al. 2014), in response to the correct way it is treated by the organization.

As for the normative commitment, this concerns the moral duty that the employee has towards the organization and makes it remain the same, that is, it is the moral duty and the obligation to pay the debt (Meyer and Parfyonova 2010). The normative commitment develops when the employee internalizes a set of rules that refer to proper conduct and creates a feeling of obligation towards the organization, feeling that he must return certain benefits that he received from it (Meyer and Allen 1991).

The interest in the study of organizational commitment, especially the affective and normative commitment, is due, in large part, to its impact on turnover intentions. In the three-component model of Meyer and Allen (1991), both the affective commitment and the normative commitment are antecedents of the intention to leave, and the relationship between the constructs is negative. For Jaros (1997) e Wasti (2003), both affective and normative commitment have a negative effect on turnover intentions. However, these authors also mention that among the three components of organizational commitment, the one that is a better predictor of turnover intentions is affective commitment. In this sense, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 4.

Organizational commitment (affective and normative) has a significant and negative effect on turnover intentions.

The Serial Mediating Effect of Perceived Employability (Internal and External) and Organizational Commitment (Affective and Normative)

When an organization has practices that promote the development of specific competencies in its employees, according to the Human Capital Theory (Schultz 1961), to make them feel essential in the organization where they work (Becker 1965) and develop a greater perception of internal employability. This theory also suggests that when the development of general competencies is promoted, the employees’ perceived external employability increases (Becker 1965; Lynch and Cross 1991; Mincer and Higuchi 1988). Perceived internal employability must be controlled by HR department of an organization, since, when it considers the loss of its most valuable employees a risk, the emphasis will be to promote the development of specific competencies of its employees, which will influence a greater perception of internal employability and a feeling of loyalty to the organization, and make them want to remain (Roehling et al. 2000).

In a study by Benson (2006), results indicated that competencies development had a significant and positive effect on organizational commitment, and a negative effect on turnover intentions. Based on the premise of social exchanges (Blau 1964), for an organization’s employees, OPCD is seen as a benefit, contributing to organizational commitment development and the desire to remain in the organization, reducing their intentions to leave the organization. This is the reasoning that leads us to study the indirect effect of organizational commitment on the relationship between OPCD and turnover intentions.

The reasoning that leads us to this indirect effect in series, that is, to this double mediating effect of perceived employability (internal and external) and the organizational commitment (affective and normative) in the relationship between the OPCD and the turnover intentions, is that the perception of OPCD contributes to a better perception of employability of employees (Baruch 2001; De Cuyper et al. 2008), and, in response, based on the premise of social exchanges (Blau 1964) and the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner 1960), they pay back by developing their commitment to the organization (De Cuyper and De Witte 2011), and reducing turnover intentions (Allen and Meyer 1996; Benson 2006), as a feeling of loyalty to it. Our second objective is to study the indirect serial effect of perceived employability and organizational commitment in the relationship between the OPCD and turnover intentions. For this, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 5.

Perceived employability and organizational commitment, both represent a serial indirect effect in the relationship between OPCD (training, individualized support, and functional rotation) and the turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 5a.

Perceived employability and organizational commitment, both represent a serial indirect effect in the relationship between training and turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 5b.

Perceived employability and organizational commitment, both represent a serial indirect effect in the relationship between individualized support and turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 5c.

Perceived employability and organizational commitment, both represent a serial indirect effect in the relationship between functional rotation and turnover intentions.

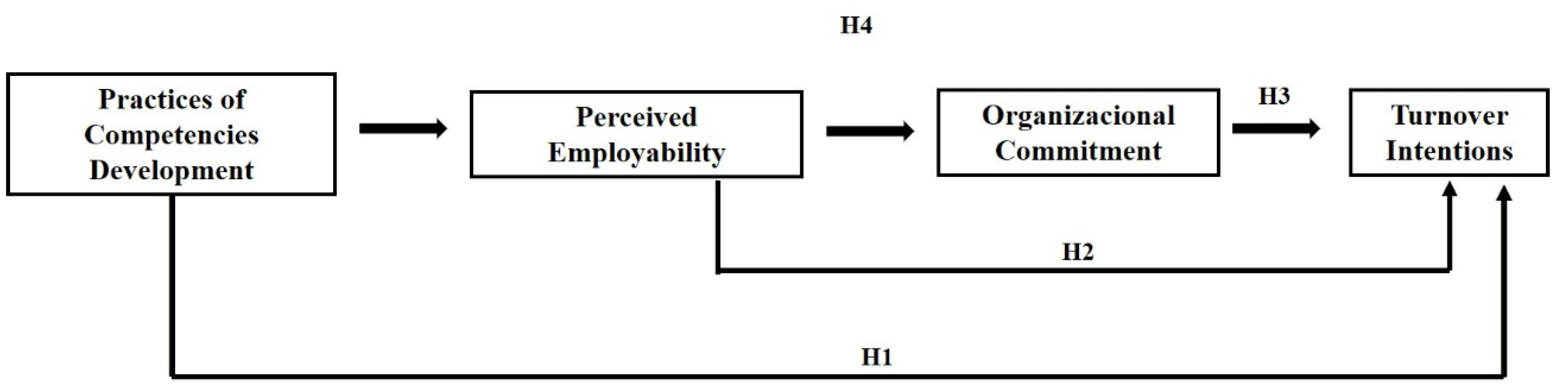

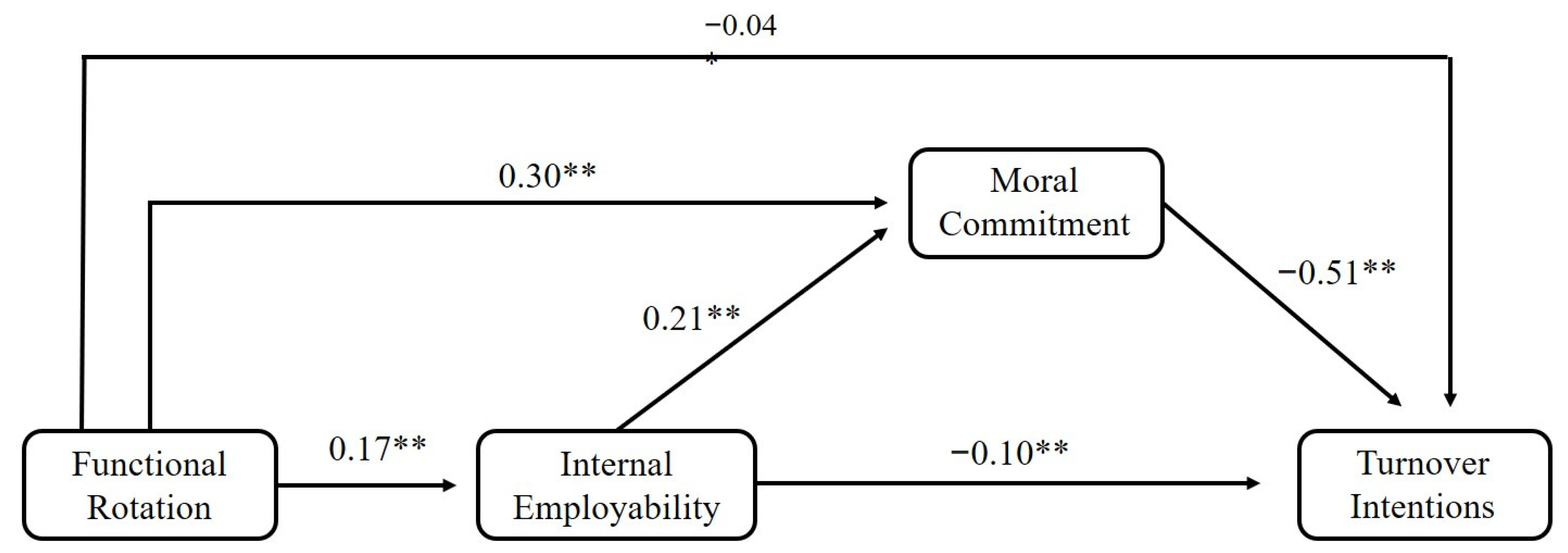

To integrate the various hypotheses formulated in this study, a theoretical model was developed (Figure 1), in which the expected associations between the constructs are synthesized.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

2. Method

2.1. Procedure

This study had the voluntary participation of 2113 individuals, all of whom have been working for at least 6 months in organizations based in Portuguese territory. After the questionnaire was created, it was placed online on the Google Docs platform, with the respective link sent via email or via LinkedIn to researchers’ contacts between January and July 2019. Therefore, the sampling process was the non-probabilistic, convenient, and intentional snowball type (Trochim 2000).

The online questionnaire contained information about the objective of the study, as well as the confidentiality of the answers. It consisted of six questions to characterize the sample (age, sex, educational qualifications, seniority in the organization, tenure and type of employment contract) and four scales (OPCD, organizational commitment, employability and turnover intentions).

2.2. Participants

Although 2113 responses were given, only 2099 were validated, 14 individuals were considered outliers. Of the 2099 participants, 1053 (50.2%) were male, with an average age of 35.88 years (SD = 9.47) with a minimum of 19 years and a maximum of 72 years. As for educational qualifications, 336 (16%) have the 12th grade or lower, 948 (45.2%) have a degree, and 815 (38.8%) have a master’s degree or higher. About the employment contract, 270 (12.9%) have an uncertain term contract, 426 (20.3%) have a fixed-term contract, 1267 (60.4%) have no fixed term, and 136 (6.5%) another type of contract. Regarding organization tenure, 657 (31.3%) have been in the organization for a year or less, 829 (39.5%) between 1 and 5 years, 241 (11.5%) between 5 and 10 years, 157 (7.5%) between 10 and 15 years and 215 (10.2%) for more than 15 years. As for tenure in the role, 558 (26.6%) have been playing for one year or less, 903 (43%) between 1 and 5 years, 306 (14.6%) between 5 and 10 years, 146 (7%) between 10 and 15 years and 286 (8.9%) for more than 15 years.

2.3. Data Analysis Procedure

Once the data has been collected and the database created in SPSS Statistics 25 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA), the metric qualities of the four instruments used in this study were tested. To test the validity, confirmatory factor analyses (AFC) were performed using AMOS 25 for Windows software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY., USA). The procedure was according to a “model generation” logic (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993), considering in the analysis of its adjustment, interactively the results obtained: for the chi-square (χ2) ≤ 5; for the Tucker Lewis index (TLI)> 0.90; for goodness-of-fit index (GFI)> 0.90; for the comparative fit index (CFI)> 0.90; for root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.08. Then, the internal consistency of each instrument was tested by calculating Cronbach’s alpha. For the study of sensitivity, central tendency measures such as median, asymmetry, and kurtosis were used, as well as the minimum and maximum of each item.

To test the mediation model, we used the Macro PROCESS 3.3 (Hayes, NY, USA), developed by Hayes (2013), since it allows us to test a mediation model with multiple mediators that operate in series.

2.4. Measures

The sociodemographic questionnaire was composed of six questions (gender, age, educational qualifications, seniority in the organization, seniority in function, and type of employment contract).

To measure the perception of OPCD, an instrument developed by De Vos et al. (2011), which was subject to adaptation to the Portuguese language, consisting of 12 items, classified on a 5-point Likert rating scale (from 1 “Never” to 5 “Always”). Its validity was tested through an AFC, which confirmed the existence of three factors: training (items 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8); individualized support (items 7, 11, and 12); functional rotation (items 9 and 10). It should be noted that it was necessary to remove items 1 and 6 because they have a low factor weight. The adjustment indexes obtained are adequate (χ2/gl = 4.43; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.040). Concerning internal consistency, the Cronbach alpha values presented are as follows: 0.88 for training; 0.71 for individualized support; 0.78 for functional rotation.

Perceived employability was measured using the instrument developed by De Cuyper and De Witte (2010), consisting of 16 items classified on a five-point Likert rating scale (from 1 “Totally Disagree” to 5 “Totally Agree”). This instrument consists of two dimensions: perceived internal employability (items 1, 2, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 and 14); perceived external employability (items 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15 and 16). A two-factor AFC was performed, and the adjustment indexes obtained proved to be adequate (χ2/gl = 4.38; GFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.040). There was a need to remove item 5 due to its low factor weight. Concerning internal consistency, it presents a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78 for perceived internal employability and 0.82 for perceived external employability.

Organizational commitment was measured through the 12 items that comprise the dimensions of affective commitment and normative commitment of the instrument developed by Meyer and Allen (1997), classified on a 7-point Likert rating scale (from 1 “Totally Disagree” to 7 “I agree”). Thus, a two-factor AFC was performed, but as these were strongly correlated, a new one-factor AFC was performed. According to the study by Meyer and Parfyonova (2010), it was decided to designate this union of affective commitment with the norm of “moral commitment”. Adequate adjustment indexes were obtained (χ2/gl = 4.08; GFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.038) and with regard to internal consistency, a Cronbach alpha value was obtained of 0.90.

As for the turnover intentions, they were measured through the 3 items that make up the instrument developed by Bozeman and Perrewé (2001), classified on a rating scale of 5 points (from 1 “Totally Disagree” to 5 “Totally Agree”). Since this instrument consists of only 3 items, exploratory factor analysis was performed, obtaining a KMO of 0.68 and an explained variance of 68.33%. As for internal consistency, it presents a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77.

None of the scales or the items that compose them grossly violate normality.

3. Results

First, the association between the variables under study was tested using Pearson’s correlations. Training, individualized support, and functional rotation are significantly positively associated with perceived internal employability and with the moral commitment and negatively to leave. Perceived internal employability has a significant and positive association with moral commitment and a negative with turnover intentions. As for perceived external employability, this is significantly and negatively associated with training and moral commitment and positively associated with turnover intentions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pearson Correlation Matrix.

To test H1, multiple linear regression was performed, the results of which are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression results (H1).

The results obtained indicate that training, individualized support, and functional rotation have a significant and negative effect on turnover intentions. Hypothesis 1 was confirmed.

Hypotheses 2 and 3 were also tested by performing multiple linear regression, the results of which are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression results (H2 e H3).

Perceived internal employability has a significant and negative effect on turnover intentions, while for perceived external employability this effect is significant and positive. Hypotheses 2and 3 were proved.

H4 was tested by performing simple linear regression, the results of which are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of simple linear regression (H3).

Moral commitment has a significant and negative effect on turnover intentions. Hypothesis 4 was proven.

Hypotheses 5a, 5b, and 5c were tested in the Macro PROCESS 3.3 since these are series mediating effects. Only in hypothesis 4a will the moderating effect of perceived external employability be tested since the only competence development practice to which it is significantly associated is training. Specifying, in models 1 and 2 are the results of hypothesis 5a, in model 3 of hypothesis 5b, in model 4 of hypothesis 5c.

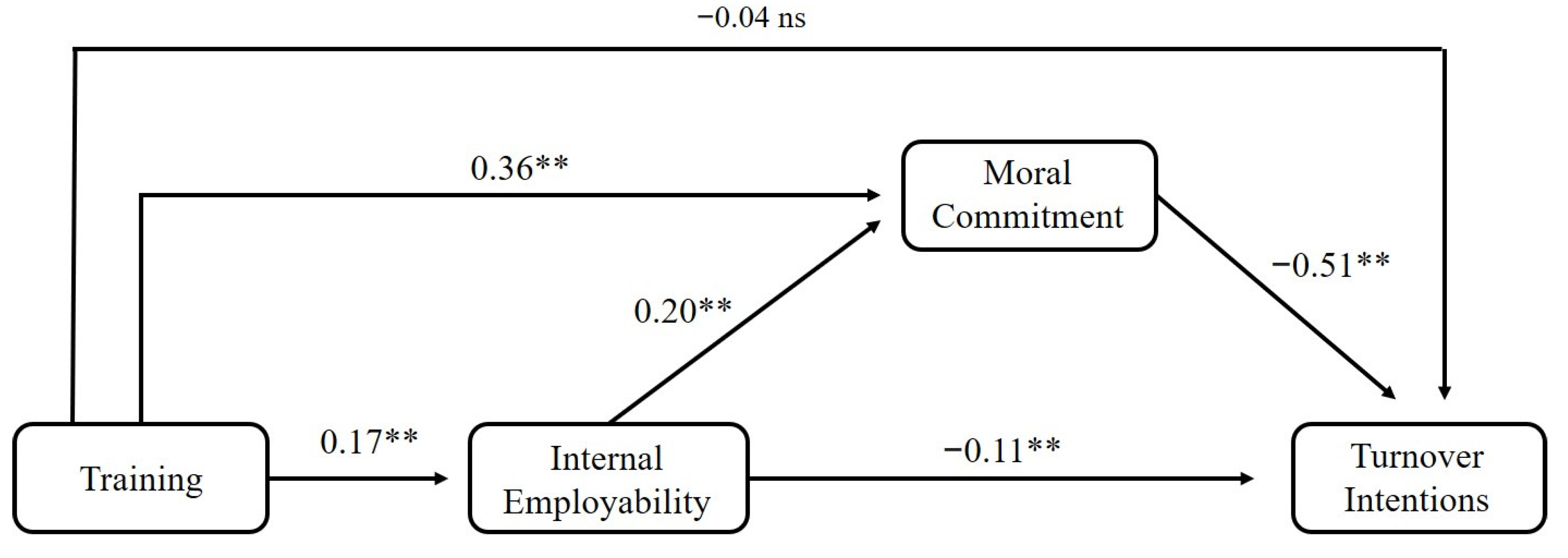

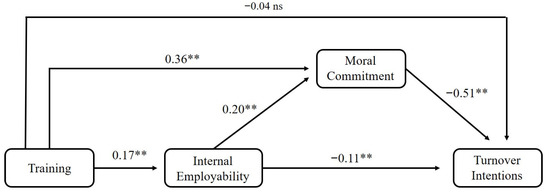

As can be seen in Table 5 (H5a), there was a significant total indirect effect since the confidence interval did not contain zero. This total indirect effect is divided into three indirect effects, all of which are significant: the series indirect effect; the indirect effect of perceived internal employability in the relationship between training and intentions to leave; the indirect effect of moral commitment on the relationship between training and intentions to leave. When the mediators were introduced into the regression equation, the direct effect of training on turnover intentions was no longer significant, which leads us to affirm that we are facing a total mediation effect (Figure 2).

Table 5.

Indirect Effects of the Model 1.

Figure 2.

Model 1. Note. ** p < 0.01.

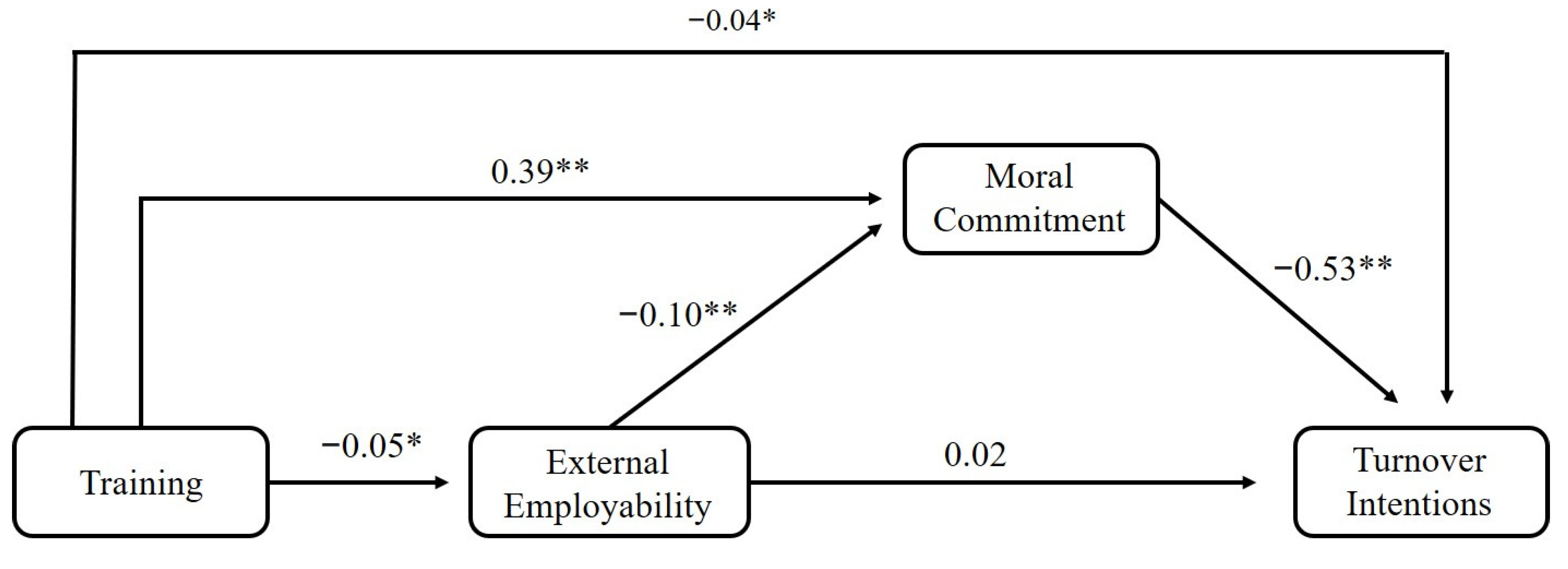

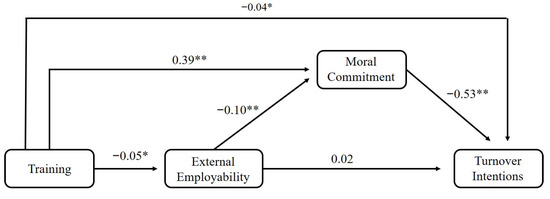

As can be seen in Table 6 (H5a), a significant total indirect effect was observed, since the confidence interval did not contain zero. This total indirect effect is divided into three indirect effects, is significant: the series indirect effect; the indirect effect of affective commitment on the relationship between formation and turnover intentions. When mediators were introduced into the regression equation, the direct effect of training on turnover intentions continued to be significant but decreased in intensity, which leads us to affirm that we are facing a partial mediation effect (Figure 3).

Table 6.

Indirect effects of Model 2.

Figure 3.

Model 2. Note. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

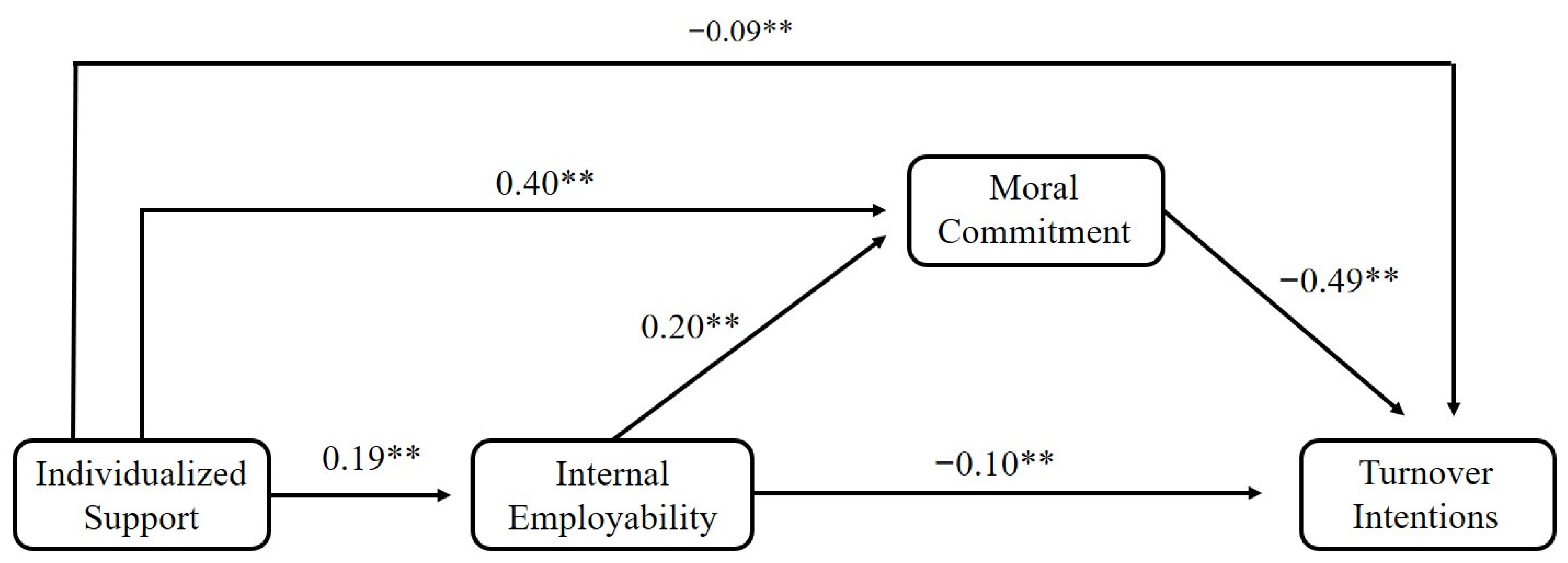

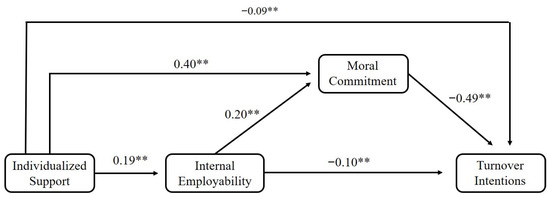

According to Table 7 (H5b), there was a significant total indirect effect, since the confidence interval did not contain zero, as did the three indirect effects: the indirect series effect; the indirect effect of perceived internal employability in the relationship between individualized support and turnover intentions; the indirect effect of moral commitment on the relationship between individualized support and turnover intentions. When the mediators were introduced in the regression equation, the direct effect of individualized support on turnover intentions continued to be significant but decreased in intensity, which leads us to affirm that we are facing a partial mediation effect (Figure 4).

Table 7.

Indirect effects of model 3.

Figure 4.

Model 3. Note. ** p < 0.01.

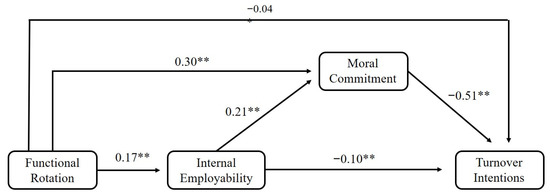

When analysing Table 8 (H5c), a significant total indirect effect was observed, since the confidence interval did not contain zero, as well as three significant indirect effects: the series indirect effect; the indirect effect of perceived internal employability in the relationship between the functional rotation and turnover intentions; the indirect effect of moral commitment on the relationship between the functional rotation and turnover intentions When mediators were introduced in the regression equation, the direct effect of functional rotation on turnover intentions continued to be significant, but decreased in intensity, which leads to affirming that we are facing a partial mediation effect (Figure 5).

Table 8.

Indirect effects of model 4.

Figure 5.

Model 4. Note. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

This study had as main objective to test the serial mediating effect of perceived employability and organizational commitment in the relationship between the OPCD and the turnover intentions.

As expected, the existence of a significant and negative effect of OPCDs on turnover intentions was proven, results which are in line with the literature (Benson 2006; Kim 2005; Rahman and Nas 2013), that when an organization invests in its employees, promoting the development of their competencies, they repay this investment by the organization, reducing their intentions to leave it, a relationship that can be interpreted as a social exchange (Blau 1964) or a reciprocal response (Gouldner 1960).

It was proved, as hypothesized, the existence of a significant and negative effect of perceived internal employability in the turnover intentions, a relationship that can be interpreted based on the Theory of Resource Conservation since employees do not want to lose this resource, thus reducing their turnover intentions (Acikgoz et al. 2016; De Cuyper et al. 2012; Hobfoll 1989; Pinto and Chambel 2008). The existence of a significant and positive effect on the relationship between perceived external employability and turnover intentions has also been proven. These results do not corroborate what the literature says since in previous studies the relationship between perceived employability (internal and external) and the organization’s turnover intentions was not significant (Sánchez-Manjavacas et al. 2014; Usmani 2016; De Cuyper et al. 2011). However, they agree with what De Cuyper et al. (2011) hypothesized in their study. These authors hypothesized a negative and significant association between perceived internal employability and turnover intentions. On the other side, between perceived external employability and exit intentions, this association would be positive and significant.

As expected, there was also a significant and negative effect of moral commitment on turnover intentions. These results are also in line with what Meyer and Allen (1991) tell us. These authors consider that the main predictor of turnover intentions is organizational commitment. For Colquitt et al. (2014), as well as for Meyer and Parfyonova (2010), this effect is the result of an exchange between the organisation and the employee, as a response to the right way he or she is treated by the organisation.

This study sought to understand which process associates OPCD with turnover intentions. The indirect serial effect of perceived internal employability and moral commitment in the relationship between the OPCD and turnover intentions was proven. When an organization provides its employees with the appropriate OPCDs to develop specific competencies, it creates the same resources that are difficult to imitate and makes them perceive high internal employability (Baruch 2001; De Cuyper et al. 2008). In turn, when feeling that the organization has invested in it, increasing its internal employability, the employee will return with a greater moral commitment (De Cuyper and De Witte 2011), a relationship that is based on the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner 1960), and that will make him try to return this investment, through the theory of social exchanges (Blau 1964), with a decrease in their intentions to leave the organization (Allen and Meyer 1996; Benson 2006). Regarding the serial indirect effect of perceived external employability and moral commitment in the relationship between the OPCD and the turnover intentions, this effect was only tested with training, since neither individualized support nor functional rotation has a significant association with perceived external employability. There was a partial serial mediating effect. It should also be noted that the association between training and perceived external employability is significant and negative, which should deserve our attention in future studies. The explanation for these results is that the instrument used measures the frequency with which employees are involved in very specific OPCDs and, these enhance the perception of internal employability (Becker 1965). According to this author, in order to increase the perception of external employability the OPCDs should be general, which is not the case in this study.

Portugal is slowly emerging from an economic crisis, in which some of our best employees left the country. It will be important that these OPCDs are implemented as they are relevant for retaining the best employees and eventual reintegration of those who left the country in this period.

4.1. Limitations and Suggestions

This study has some limitations, such as the fact that it is a cross-sectional study, which did not allow us to establish causal relationships between variables. Since these should only be tested in longitudinal studies to test causal relationships. To overcome the limitation regarding the type of questionnaire used (self-report), which may have caused the results to be biased, several methodological and statistical recommendations were followed to reduce the impact of the variance of the common method (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

4.2. Practical Implications

One of the strengths of this study is the fact that it indicates the existence of a serial mediation effect of perceived employability and organizational commitment in the relationship between the OPCD (training, individualized support, and functional rotation) and turnover intentions. Another of the strong points is the significant and positive effect of perceived external employability on turnover intentions, which indicates that when general competencies are developed in the employee, he/she has a high perception of external employability, which translates into a high probability to find another job in another organization that gives you better prospects for professional development or higher levels of compensation and greater benefits (De Cuyper and De Witte 2011) and therefore, your turnover intentions increase. In a work context in which organizations must retain their best employees, as these resources are difficult to imitate and according to the “Resource-Based View” theory (Afiouni 2007; Barney 1991) they become their competitive advantage in the current labour market, they must implement specific competencies development practices appropriate to their workforce and not general competencies development practices. In this way they would develop in their employees a better perception of internal employability, which in turn would boost their greater moral commitment, making them want to stay in the organization.

5. Conclusions and Final Considerations

We perceived that our study achieved the proposed objectives, and that its conclusions contribute to the advancement of research in organizational behaviour, while being very important for organizations.

OPCDs, perceived internal employability and organisational commitment reduced turnover intentions. With regard to the perception of external employability, we found that it increases turnover intentions. This relationship should be further explored in future studies.

Perceived internal employability and moral commitment were found to be the mechanisms explaining the relationship between OPDCs and turnover intentions. These results indicate that organisations should be concerned with the development of specific competencies, as these will increase the perception of internal employability, which will also increase organisational commitment, reducing turnover intentions.

Perceived internal employability and organisational commitment are the mechanisms explaining the relationship between training and exit intentions.

This study demonstrates that the best way for an organisation to retain its employees is by promoting the development of their key competencies, which is in line with Reiche (2008). When employees feel that the organisation is concerned with the development of their competencies, their perception of internal employability will be higher (Cesário et al. 2012), making them feel more committed to the organisation where they work (Meyer and Smith 2000), and decreasing their intentions to voluntarily leave (Meyer and Allen 1991).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and F.C.; methodology, A.M. and M.J.S.; software, A.M.; validation, A.M., M.J.S. and F.C.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, A.M.; resources, A.M.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.J.S.; visualization, F.C.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, A.M.; funding acquisition, M.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that all participants before answering the questionnaire had to read the informed consent and agree to it. This was the only way they could answer the questionnaire. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, as well as that the results were confidential, as individual results would never be known, but would only be analysed in the set of all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to the fact that in their informed consent, participants were informed that the data was confidential and that individual responses would never be known, as data analysis would be of all participants combined.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acikgoz, Y., H. C. Sumer, and N. Sumer. 2016. Do employees leave just because they can? Examining the perceived employability–turnover intentions relationship. The Journal of Psychology 150: 666–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J. S. 1965. Inequity in social exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Edited by L. Berkowitz. New York: Academic Press, vol. 2, pp. 267–99. [Google Scholar]

- Afiouni, F. 2007. Human Resource Management and Knowledge Management: A Road Map Toward Improving Organizational Performance. Journal of American Academy of Business 11: 124–30. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N. J., and J. P. Meyer. 1996. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: An examination of construct validity. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 49: 252–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiegbu, I. F., H. O. Awa, C. Akpotu, and U. B. Ogbonna. 2011. Salesforce competence development and marketing performance of industrial and domestic products firms in Nigeria. Far East Journal of Psychology and Business 2: 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. B. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 17: 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch, Y. 2001. Employability: A substitute for loyalty? Human Resource Development International 4: 543–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. 1965. A Theory of the Allocation of Time. The Economic Journal 75: 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benson, G. S. 2006. Employee development, commitment and intention to turnover: A test of “employability” policies in action. Human Resource Management Journal 16: 173–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntson, E., and S. Marklund. 2007. The relationship between employability and subsequent health. Work & Stress 21: 279–92. [Google Scholar]

- Berntson, E., C. Bernhard-Oettel, and N. De Cuyper. 2007. The moderating role of employability in the relationship between organizational changes and job insecurity. Paper presented at 13th European Congress of Work and Organizational Psychology, Stockholm, Sweden, May 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bozeman, D., and P. Perrewé. 2001. The effect of item content overlap on organizational commitment questionnaire–turnover cognitions relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, V. G. 2006. Who’s who in coaching: Who shaped it, who’s shaping it. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Coach Federation Coaching Research Symposium. Edited by J. L. Bennet and F. Campone. Lexington: International Coach Federation, pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cesário, F., C. Gestoso, and F. Peregrin. 2012. Contrato de Trabajo, Compromiso y satisfacción: Moderación de la Empleabilidad. RAE 3: 345–59. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J. A., M. D. Baer, D. M. Long, and M. D. K. Halvorsen-Ganepola. 2014. Scale indicators of social exchange relationships: A comparison of relative content validity. Journal of Applied Psychology 99: 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cuyper, N., and H. De Witte. 2010. Temporary employment and perceived employability: Mediation by impression management. Journal of Career Development 37: 635–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper, N., and H. De Witte. 2011. The management paradox: Self-rated employability and organizational commitment and performance. Personnel Review 40: 152–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Cuyper, N., C. Bernhard-Oettel, E. Berntson, H. De Witte, and B. Alarco. 2008. Employability and employees’ well-being: Mediation by job insecurity. Journal of Applied Psychology 57: 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper, N., S. Mauno, U. Kinnunen, and A. Mäkikangas. 2011. The role of job resources in the relation between perceived employability and turnover intention: A prospective two-sample study. Journal of Vocational Behavior 78: 253–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cuyper, N., S. Raeder, B. I. Van der Heijden, and A. Wittekind. 2012. The association between workers’ employability and burnout in a reorganization context: Longitudinal evidence building upon the conservation of resources theory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 17: 162–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A., and S. De Hauw. 2009. Building a conceptual process model for competency development in organizations: An integrated approach. Paper presented at 14th European Congress of Work and Organizational Psychology, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, May 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, A., S. De Hauw, and B. I. J. M. Van der Heijden. 2011. Competency development and career success: The mediating role of employability. Journal of Vocational Behavior 79: 438–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Witte, H. 2005. Job insecurity: Review of the international literature on definitions, prevalence, antecedents and consequences. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology 31: 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., S. Armeli, B. Rexwinkel, P. D. Lynch, and L. Rhodes. 2001. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, A. C. C., and M. T. L. Fleury. 2000. Estratégias Empresariais e Formação de Competências. São Paulo: Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A. W. 1960. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review 25: 161–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M., L. Curtayne, and G. Burton. 2009. Executive coaching enhances goal attainment, resilience and workplace well-being: A randomised controlled study. The Journal of Positive Psychology 4: 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. 2013. An Introduction To mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan, M. M., and P. C. Flood. 2000. An exploration of the relationships between the adoption of managerial competencies, organizational characteristics, human resource sophistication and performance in Irish organizations. Journal of European Industrial Training 24: 128–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C., and G. Jones. 2004. Strategic Management: An Integrated Approach, 6th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E. 1989. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist 44: 513–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaros, S. J. 1997. An assessment of Meyer and Allen’s (1991) three component model of organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behaviour 51: 319–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K. G., and D. Sörbom. 1993. LISREL8: Structural Equation Modelling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chicago: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. 2005. Factors affecting state government information technology employee turnover intentions. American Review of Public Administration 35: 137–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, C. H., and N. T. Bruvold. 2003. Creating value for employees: Investment in employee development. International Journal of Human Resource Management 14: 981–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, R. L., and K. F. Cross. 1991. Measure Up—The Essential Guide to Measuring Business Performance. London: Mandarin. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, O. F., Q. Abbas, T. M. Kiyani, K. U. R. Malik, and A. Waheed. 2011. Perceived investment in employee development and turnover intention: A social exchange perspective. African Journal of Business Management 5: 1904–14. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. P. 2014. Organizational commitment. In Human Resource Management, 3rd ed. vol. 5 of the Wiley Encyclopedia of Management. Edited by D. E. Guest and D. Needle. Chichester: Wiley, pp. 199–201. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. P., and N. J. Allen. 1984. Testing the “side-bet theory” of organizational commitment: Some methodological considerations. Journal of Applied Psychology 69: 372–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., and N. J. Allen. 1991. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review 1: 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., and N. J. Allen. 1997. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J. P., and C. A. Smith. 2000. HRM practices and organizational commitment: Test of a mediation model. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences 17: 319–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. P., and N. M. Parfyonova. 2010. Normative Commitment in the Workplace: A Theoretical Analysis and Re-Conceptualization. Human Resources Management Review 20: 283–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincer, J., and Y. Higuchi. 1988. Wage structures and labour turnover in the United States and Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 2: 97–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W. H. 2015. The incremental validity of organizational commitment, organizational trust, and organizational identification. Journal of Vocational Behavior 88: 154–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyhan, B. 1998. Competence development as a key organizational strategy experiences of European companies. Industrial and Commercial Training 30: 267–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J. 1996. Competitive Advantage through People: Unleashing the Power of the Work Force. Boston: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, A. M., and M. J. Chambel. 2008. Abordagens teóricas no estudo do burnout e do engagement. In Burnout e Engagement em Contexto Organizacional: Estudos Com Amostras Portuguesas. Edited by A. M. Pinto and M. J. Chambel (Orgs.). Lisboa: Livros Horizonte, pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. MacKenzie, J. Y. Lee, and N. P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, W., and Z. Nas. 2013. Employee development and turnover intention: Theory validation. European Journal of Training and Development 37: 564–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiche, B. S. 2008. The Configuration of Employee retention practices in multinational corporations foreign subsidiaries. International Business Review 17: 676–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehling, M., M. Cavanaugh, L. Moynihan, and W. Boswell. 2000. The nature of the new employment relationship: A content analysis of the practitioner and academic literatures. Human Resource Management 39: 305–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Manjavacas, A., M. Saorín-Iborra, and M. Willoughby. 2014. Internal employability as a strategy for key employee retention. Innovar 24: 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T. W. 1961. Investment in Human Capital. The American Economic Review 51: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, L. M., L. E. Tetrick, P. Lynch, and K. Barksdale. 2006. Social and economic exchange: Construct development and validation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 36: 837–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochim, W. 2000. The Research Methods Knowledge Base, 2nd ed. Cincinnati: Atomic Dog Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Usmani, S. 2016. Perceived internal employability and leader member exchange as a way to reduce intention to quit via commitment. Humanities and Social Sciences Review 5: 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wasti, S. A. 2003. Organizational commitment, turnover intentions and the influence of cultural values. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 76: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittekind, A., S. Raeder, and G. Grote. 2010. A Longitudinal Study of Determinants of Perceived Employability. Journal of Organizational Behavior 31: 566–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).