Abstract

This article analyses how social times are structured for cooks in France’s hospitality sector. Observations, in situ studies in restaurants and 43 interviews constitute the primary data of this research. We first examine the context, with data on employment, food practices, the socialisation of cooks and work organisation. Then, we describe their time configurations. The results highlight a dual operating system, with an all-day work schedule on one side and a schedule with a daily break and mandatory free time on the other. The results show a variability in the practices of the cooks, with five different time configurations using the variables of work and break time. The break schedule can be interpreted as a time configuration for (1) unpaid overtime for the benefit of the employer, for (2) non-work obligations and as (3) a work schedule including free time at the individual’s disposal. The continuous workday can be seen as (4) a negation of sociability and time needs associated with the break schedule, and as (5) an opportunity to rebalance social times and synchronise with the private sphere.

1. Introduction

The social times of cooks in France are quite complex,1 even beyond the justified stereotype of long working hours (Stier and Lewin-Epstein 2003). Social times refer to the structure of employment, socialisation and “choices” made by mediating social entities, such as the productive organisation of work, work culture or family configuration (Fusulier and Nicole-Drancourt 2019; Barbier et al. 2020). The temporal structure of the workday for caterers and cooks is organised in two main ways: the first features work timeslots exclusively before and after lunch and dinner; the second encompasses a single continuous working period before, during and after a meal (at lunch time and/or dinner time). To manage working time, restaurant and hotel owners and public authorities in France, and elsewhere, have introduced a “break”—generally from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m.—between lunch and dinner. However, since the 1970s, both the hospitality sector and the profession of cooking have changed (Poulain 1992; Mériot 2002; Laporte 2010; Monchatre 2010; Fellay 2009, 2010). These changes have been part of a broader evolution. Our research shows that, for over thirty years, the conditions of social activities—working time, free time and family time—have undergone a heterogeneous evolution, which is increasingly dependent on production, business and market constraints in a global context (Thoemmes 2013). In this study, we wish to analyse how the temporalities of cooks fit into this context by identifying the factors that structure the organisation of activities and practices (Bouffartigue and Bouteiller 2012). How and why are different time frames employed? What happens to the individuals in each time frame? How are social times structured? Which overall factors influence the time configurations?

In the first instance, we will (1) provide an overview of our approach to the study of time, including the theoretical framework and methods. We will then (2) investigate the context, using employment and working time data and in consideration of the importance of food practices and work organisation for the social times of cooks. Finally (3), we will analyse the time configurations of cooks, including two different worktime organisations (all-day and break schedule).

While discussing reasons for the trend of opting for a continuous workday, we will also (4) look at forms of resistance, including food practices that may maintain the dominant discontinuous time configuration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Our Approach: Working Time, Social Times and Temporalities

Time relates to occupations and employment in many ways. Several definitions allow us to distinguish different levels of employment-related time (Thoemmes 2019). The first concept of working time relates to salaried employment and describes the time during which an employee is at the disposal of their employer. This daily, weekly or annual working time is governed by legal standards and rules that have resulted from collective bargaining between trade unions and employers. The concept of working time can then be extended to cover time spent on any non-salaried work activity, such as that of the self-employed or even unpaid work in the private sphere (domestic work, care, education, etc.). Nevertheless, labour laws and protections (maximum working hours, minimum rest periods) do not automatically apply to all of these ways of organising working time.

The second important concept concerns the time spent on a variety of activities, including work, school, training, leisure, family, rest (including food intake and sleep), domestic activities, civic commitments, etc.2 These times devoted to, and delimited by, activities are identified by us as social times. When related to employment, the question of how to arrange these social times emerges, and in particular how to configure professional and non-work activities. Taking care of a sick relative, picking up a child from school or carrying out administrative procedures require the ability to organise social times.

A third notion differs from these times by duration or types of activity. When examining the qualities or the character of what takes place in time and how someone lives it, we speak of temporalities. This notion questions meaning, experience, values and relationships; in short, the subjective side of time. From this perspective, a “long duration” can, for example, refer to any activity considered as “monotonous” or “boring”. The objective and subjective sides of time will help to explain and understand time configurations.

For example, one of the central questions addressed in this paper will be the organisation of working time with a compulsory two-hour break within the workday. What is the meaning of this period? Is this time “off” or “free time”? This second question arose in classical French sociology, well after Durkheim’s notion of social time (Durkheim [1912] 1998), in the 1950s and concerned the content and meaning of time off (Thoemmes 2019). Two points of view opposed each other on this question, that of Georges Friedmann (1902–1977) and that of Joffre Dumazedier (1915–2002). For the former, it is technological civilisation, with its instruments and machines, that is at the origin of free time, as separated from working time. “This separation is ordered by the organisation of work, its discipline, by the division of tasks, the structure of enterprises, the cohesion of the industrial armies that populate them” (Friedmann 1960, p. 552). Friedmann then identifies two areas of struggle: working time itself and the time outside of work and suggests distinguishing “carefully between liberated time and free time, reserving the latter term for the duration, preserved from all the above-mentioned necessities and obligations” (Friedmann 1960, p. 556).

In this debate, another point of view emerges from the work of Joffre Dumazedier. From the outset, he situates the emergence of leisure in the possibilities offered by the considerable reduction in the duration of work, daily, weekly, and annually. The mere fact that work no longer has a monopoly on activity constitutes an important break. “Thus, in the life of a worker, the rise in the standard of living has been coupled with an increasing rise in the budget for free time. (...): A new time was born for his acts and his dreams” (Dumazedier 1960, p. 564). However, the time freed up also includes activities that are not leisure: family, social and personal obligations, a second job. Moreover, there is a grey area between leisure and work, called “semi-leisure”, where an obligation exists in a variable way, as is the case for cooks who are on a break schedule. Obligations coexist with different types of arrangements. The differentiation of temporalities according to the sphere of activity (work, family, etc.) accompanies the mutation of social times centred on a dominant time (the time of production) towards more negotiated times (Dubar 2004). Approaches to “reconciling” social times shift the focus to the work-life balance and the difficulty of managing both at the same time (Tremblay 2008). Our approach further considers that social times originate in social rules and are set up by social regulations (Reynaud 1988) including political regulations (De Terssac et al. 2004). Those rules may be analysed by research and fieldwork about practices and representations of time. The aim of the analysis is to apprehend time configurations (Elias [1970] 1981) by characterising corresponding social rules (Reynaud 1979). Those time configurations may be subject to discussion beyond the localised situations we investigated. Our intention is to link working time, social times, and temporalities, as exposed above, to understand and explain time obligations and choices of cooks in France.

2.2. Methods

This article is based on four types of quantitative and qualitative data: (1) public, national and European statistical data on occupations and industry (hotels and restaurants) in the European and French economies; (2) secondary data from a literature review; (3) data deriving from interviews with cooks; (4) data from observations in catering establishments.

2.2.1. National and European Statistics

In the contextualisation part of this article, descriptive data about the occupation of cook is used. We used the statistical data produced by the Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques (Drees, Ministry of Solidarity and Health, Paris, France), a department of the central administration of the health and social ministries in France. For the weight of tourism in the European economy, and the dynamics of the hotel and restaurant sectors, data and analyses produced by the European Union were employed.

2.2.2. Literature Review

The literature review, centred on scientific papers, was completed using data from professional journals. They provide the possibility of studying in detail the socio-technical contexts in which cooks work. In a recent historical perspective, over the period 2010–2020, we studied four professional journals (Le Chef, Grandes Cuisines, Neo Restauration and Hôtellerie-Restauration). The journals show the discourse of professionals and indicate how views are constructed within the study population. We used the data from biographical interviews to describe and understand cooks’ socialisation processes.

2.2.3. Interviews with Cooks Who Became Cookery Lecturers (n = 43)

Data collected during a research program on cookery lecturers in French public hotel education (Laporte 2010) was employed. The particularity of this population is that they worked as cooks before becoming teachers. The accounts of their careers therefore provide relevant data on the management of social times at different points in their careers. Thus, the 43 biographical interviews of the cookery lecturers retrace the trajectories and life cycles of the individuals.

“The essential thing is to be able to place a professional activity in a temporal dynamic, in a working life that includes entry into the profession or job, the course of the activity, the turning points, the anticipation, the successes and failures.”(Dubar and Tripier [1998] 2005, p. 95).

2.2.4. Observations in French Restaurants

Our research is also based on observations carried out in French restaurants, selected according to the following variables: type of industry (food cost sector or food profit sector), size (from a few dozens of meals up to several thousand), daily working time (continuous or with a “break”) and production rationale (just-in-time or delayed). This in-situ study of restaurants was first executed over short observation periods (from 1 to 7 days) then over longer periods (from 2 to 4 months).

3. Employment Data, Food Practices and Forms of Work

3.1. Time and Employment

In 2016, tourism-related economic activities employed more than 13 million people in the European Union (EU). The hotel and restaurant industry has grown considerably in this area, with nearly 8 million people working in the food and beverage sector (Bovagnet 2005). In recent years, the sector has grown faster than average employment. Part-time work is more prevalent than in other economic sectors: part-time jobs accounted for 24% of all tourism jobs in 2017, compared with 18% in the European economy as a whole. Nevertheless, in almost all European countries, full-time employment in the hospitality industry is higher than part-time. In the EU, a full-time employee works 40.3 h per week in a typical workweek. Employees in this sector work one hour more per week than other employees. The average working time, which generally includes part-time work, conceals the fact that two thirds of the countries are above the EU average of 39.6 h per week (Eurostat 2022). According to the United Nation World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the sector is also highly dependent on tourism, which implies an increased use of seasonal work: the proportion of seasonal work in employment varies between countries, from 26% in Austria to 47% in Spain and over 50% in Italy. It is worth mentioning the high percentage of women and men working on Saturdays and Sundays: 72% of women and 84% of men work on Saturdays; 60% of women and 72% of men work on Sundays (UNWTO and ILO 2014).

The traditional notion of a two-day weekend means almost nothing in the sector. Various research reports point to a generalised specific risk for employees working in split shifts. We will also consider the “break” during the day, which implies that employees only work during peak hours, with time off in between. According to reports, employers resort to this solution when there is not enough work during periods without customers. The profession of cook, which employs approximately 372,000 people in France, has steadily grown over the past 30 years, due to the growth of tourism activities and the structuring of the food cost sector. In the food cost sector, full-time cooks very often have atypical Saturday hours (69% in 2009, 52% in 2011), and/or Sunday hours (54% in 2009, 31% in 2011), or even night hours (16% in 2011). Nearly two thirds of work in hotel and restaurant companies, which are mostly small (93.74% of hotel and restaurant companies have 0 to 9 employees)3 and carry out their professional activity in a just-in-time approach, must adapt their working time management to fit in with the temporalities of the market. The remaining third work for public establishments and other food cost establishments in industry, education, or medico-social services. The proportion of women employed in the sector is increasing—30% in 1982–1984 versus 35% in 2017–2019 (Dares 2021)—and so is slightly changing the “male” image of the profession. The level of qualification is slowly improving, with only 4% of workers with higher education degrees in 2009–2011. Although secondary school vocational training (CAP) and technical certificate at secondary school level (BEP) remain the major level of qualification (44% in 2009–2011), 30% have no diploma or a general education certificate. Finally, the proportion of permanent contracts is high in France (80%) and part-time work concerns only 22% of employees (Ast 2012).4

3.2. Diversity of Workplaces

Commercial catering is extremely fragmented into sub-segments, which have only their profitability objective in common. According to our observations in the field (Table 1), the workplaces of cooks are many and varied: gastronomic restaurants, theme restaurants, brasseries, fast-food outlets or hotel restaurants. The lengthening of free time, the growth of tourist activities (Cousin and Réau 2009), and the increasing concentration of the population in urban areas have boosted commercial catering in all its forms. In addition, the emergence of hotel and restaurant chains in the late 1960s transformed part of the labour and employment market (Monchatre 2011). However, most restaurants are run by independent managers.

Table 1.

List of restaurants and observation periods.5

The contract catering market, clearly identified in the field of school, medical-social and corporate catering, has gradually become structured (Laporte [2012] 2018a, [2012] 2018b). Large industry and service companies have favoured the emergence of company restaurants at different times depending on the evolution of the economic sectors of the countries involved (Laporte and Poulain 2014). Reinforced by increasing urbanisation and longer commuting times, corporate catering has expanded the job market for cooks. The decentralisation public policies of the early 1980s transferred the management of school restaurants to local authorities and encouraged them to pool their resources. Working hours in the catering industry have been partly shaped by adapting the forms of work organisation to the temporalities of consumers or, ultimately, to the peak hours of the main food intakes.

3.3. Meals: Time Frames, Structures and Types

Our approach integrates “the intuition that food practices are among those that contribute most to shaping social times and that they are, in turn, strongly influenced by the important part they take in the organisation of time schedules” (Aymard et al. 1993). In a marketing approach to catering, some economic actors have sought to design types of food offers that are in line with consumption practices. However, as our research emphasises, certain fundamental characteristics of food practices remain to be considered, including the timing, structure, and type of meal (Poulain [2002] 2011; Poulain 2012, 2017).

In France, eating is characterised by three main meals a day and synchronised timing, i.e., a high concentration of people who eat lunch and dinner at the same time. Since the early 1960s, this distribution of daily food intake has been rather stable (Baudier et al. 1996; Guilbert and Perrin-Escalon 2002; De Saint Pol 2006; Fischler and Masson 2008; Poulain et al. 2010). However, practices vary in other European countries. For example, dinnertime is said to be the high point of daily food intake for Anglo-Saxons (Murcott 2012). The ambition of commercial catering is to feed all customers while adapting to the social (labour laws) and economic (production and distribution costs) constraints of different countries. The Spanish or the inhabitants of Nordic countries (Holm 2012) do not eat at the same time as the French. Thus, the distribution of daily food demand can be extremely strong depending on where one eats. The professional temporalities of cooks are affected by this variability, which shows that the management of work time depends on food intake times. Meal structures vary from country to country and, for France, the INPES health and nutrition barometers reveal that four-course meals have decreased from 25% to 17% and three-course meals from 37.8% to 33% (Baudier et al. 1996; Guilbert and Perrin-Escalon 2002; Poulain et al. 2010). Thus, there is a continuous trend towards simplification, which requires adaptation of technical systems. Finally, the type of services provided also depends on social and cultural determinants, which involves adjusting organisation, whether one focuses on breakfast, lunch, or dinner. When McDonald’s opened in France in the early 1970s, its concept was based on providing meals at any time of the day with little variability in demand. But the specific eating practices in France – synchronised meals, meal structure and type of service – forced the American group to rethink the organic needs (facilities, equipment) and personnel, in short, to reconsider its forms of organisation. Thus, the practices of the eaters influence the technical solutions necessary to meet needs that vary according to the different socio-cultural areas.

3.4. Cooks’ Socialisation and Time Standards

According to our observations and interviews, very early in their career, internships socialise cooks to work with a “break”. The CAP trains workers in small family restaurant settings, which adapt to the temporalities of the customers. At this stage, the young apprentice or trainee acquires professional norms such as “I am asked to work long hours” or “the customer comes first”. The structuring of vocational training in the hotel industry, including internships at all levels, contribute to socially shaping the relationship of cooks to working time. The professional socialisation of cooks (Dubar 2002) imprints representations of social temporality in which the “break” is the reference model. Until the early 1970s, young cooks did their internship almost exclusively in commercial restaurants or hotel restaurants, where the workday included a “break”. For several decades, hotel schools promoted this model, a legacy of gourmet restaurants, and organised internships for cooks in establishments “with a break”. From the 1950s onwards, professional schools in the hotel industry recruited professionals from companies who, in these schools, implemented a relationship to working time “with a break”. Even if it can be said that each individual has their own way of approaching and managing time-related skills, the pressure of training institutions on working time has reinforced the prevalence of time organisation as experienced by young cooks. Their professional socialisation, from an early age through apprenticeship or initial training, shapes the professional ethos (Weber [1905] 1994) with representations of an “endless” working time.

Hotel schools and their teachers have been immersed in these social representations of working time (Laporte 2010). Generally speaking, our interlocutors and observations in the restaurants (Table 1) show that the norms, values, or attitudes in hotel schools and in companies have generated standardised representations of a never-ending working time.

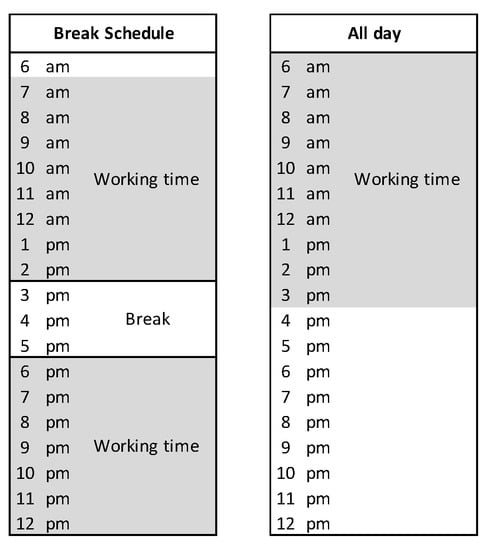

3.5. The “Break” as a Dominant Time Model

When working with a “break”, the cooks’ days depend in part on the temporalities of the eaters. The restaurants are open every day of the week, at lunch and/or dinner time. The different periods of the year as well as their geographical location (by the sea or in the mountains, for example) can generate a certain seasonal activity. Work is not regulated in a homogeneous way from one restaurant to another, due to the diversity of commercial activities. Cooks work when people are eating, which means that the core of their professional activity is concentrated on lunch and dinner time. Like many service sector employees, such as caregivers (Aubry 2012) and hospitality professionals, they must adapt to the needs of their customers and staff must work “off the clock” (Barbier 2012), with atypical evening and/or weekend hours. This split schedule prevails in commercial catering, although in some large establishments, the organisation of morning and evening shifts has put in place a so-called continuous schedule, without a “break” (Figure 1). The cooks work before, during and after lunch or dinner. Their activity is therefore concentrated either on morning and noon, or on afternoon and evening. This model is found in large organisations with long hours, such as fast food or fine dining establishments. In other cases, when organisations have adopted a just-in-time production-distribution logic, cooks work every day, all year round and especially at lunch and dinner time. Therefore, some medical and social establishments operate on a “break” basis. The pathologies of patients contribute to making medical catering more complex. The size of the institutions and the multiplicity of catering locations make it even more difficult to control the distribution of meals. The evolution of organisational forms, in particular with a moment of food production completely disconnected from the moment of consumption, has affected the temporalities of cooks.

Figure 1.

Work time organisations.

Thus, the “break” model requires flexible time availability (Bouchareb 2012), with workdays and rest periods constantly changing from week to week. The way cooks organise their other social, family, or leisure time is linked to their ability to negotiate their work schedules with their employer, but also with their colleagues. The organisation of their marital and family life (Haicault 1984) depends on the ability of individuals to coordinate work constraints with the temporalities of other family members. This is all the more true in the case of “highly committed” professionals (Jacobs and Gerson 2001). Like many positions in the medical field, such as nurses (Bouffartigue and Bouteiller 2006), cooks must be able to adapt to flexible work schedules (Boulin et al. 2006).

In summary, the “break” is prevalent in the restaurant industry. It is mostly used in commercial catering and partly used in the food cost sector in the medical field. For other food service sectors, all-day schedules are predominant.

3.6. All-Day Duty

Continuous hours are only implemented in school or workplace catering. With the emphasis on the midday meal, a break in the workday is unnecessary and other time frames are set (Grossin 1996). In primary and secondary schools and at university, food services are part of the school timetable or academic time as defined by the state and mainly provide midday meals on working days. Some exceptional situations require cooks to work at times close to those of commercial catering, in the evening or on weekends in the case of boarding schools or university restaurants.6 The working day starts with a long preparation period, from early in the morning (sometimes as early as 7 a.m.) until 11:30 a.m. This is the beginning of the day’s production process and includes all food preparation tasks. The cooks eat their meals before their customers’ lunch break so that they are available to serve the meals. Then comes the “rush”, the hectic time when they serve the meals prepared in the morning. This is an increase in workload in a very short period of time. Legitimisation processes come into play, as the professionals must demonstrate their ability to master this particular time pressure. Finally, after the meal, the cooks deal with the uneaten food, the cleaning of the kitchen and the administrative management.

Workplace catering is adapted to the working hours of companies or public administrations. Most often the restaurants operate on working days with a preference for lunchtime. In France, this is the case for large industrial groups and service companies, as well as for public administrations and organisations. To provide meals to workers and civil servants, project managers have devised organisational systems in which all-day tasks prevail. As in school catering, work is organised around the lunch break and the work units are shaped on the same pattern. The only changes, beyond the work environment and types of eaters, are the start and end times of the workday. While fairly stable in schools, these may vary in workplace catering, where large industrial companies have introduced shift production processes (2 × 8 h or 3 × 8 h). In this case, the starting times are variable: early morning, mid-afternoon, or evening. Nevertheless, the principle of continuous working hours applies.

4. What Are Cooks’ Time Configurations?

According to our approach, we consider three levels of time: working time, social times, and temporalities. The two models of working time – including a break or all day –found in different proportions in the restaurant field, shape cooks’ experience of the social temporalities that follow. We anchor cooks’ time configurations in rules that combine organisational choices and individual needs. The collective nature of these rules (Reynaud 1988) produces a specific combination of constraints and choices, or as the author puts it, of autonomy and control. We will describe these rules: first the break model, then the continuous working time model.

4.1. The Break

4.1.1. “Compulsory-Free’ Time

Following the analysis of Friedmann (1960) and Dumazedier (1960), “non-working” time must be analysed. We use the term “compulsory free time” to reconcile autonomy and constraints. And yet, this oxymoron is the best way to describe the “break”. A parallel can be drawn with the obligations of domestic work, where free time, especially that of women, is mobilised by tasks such as “grocery shopping” and “cleaning” (Glaude and De Singly 1986).

Historically, due to legal limitations on working time, social partners have agreed to regulate the time of cooks by concentrating their working time on mornings and evenings. Thus, cooks employed in catering facilities are required to have “free time” between lunch and dinner. This “in-between” time, which is compulsory and free, is used to balance “social times”. It also appears to be particularly penalising in terms of transportation, time spent in the workplace and management of atypical schedules. The schedule arrangements will be detailed here from the most restrictive to those leaving the most freedom to the individual. According to cooks, the “break” is first perceived as time devoted to the employer, then as time that can be used for implicit obligations such as household activities, or finally, for individual leisure activities.

4.1.2. Extra Time to the Benefit of the Employer

Cooks’ first and most common approach to “break time” is that it is a time appropriated by employers as an additional resource to regulate their organisation’s workload, either by extending employees’ working time or by requiring other related administrative and managerial tasks. Cooks’ value systems clearly suggest the confiscation of this free time by their employers. In their professional representations and practices, a restaurant employee “never complains” about working time or free time, which is embodied in part by the “break.” This time is used for customer service. The working hours and its consequences on daily life have increased tension and put extra strain on cooks, who are forced to choose between family, leisure and working time. The pressure of the professional body strongly influences their choices, as the representations stem from questions of solidarity and professional ethics. This professional characteristic does not really correspond to the stereotypes of the French “35-h society” and the increase of free time (Viard [2002] 2004). Cooks find it difficult to let go of the moral duty that prevents them from leaving the workplace if there is work left.

In seasonal food service establishments, the actual workload requires employees to work longer hours. In this case, employers use the “break” to increase productive capacity.

“When lunch service is over, the chef sometimes asks us to prepare for evening service or upcoming events. Sometimes it’s pretty hard, they make us stay in the afternoon even though I only get paid for the lunch and evening services.”[Clément, 38 years old, cook in a commercial restaurant establishment]

“At the end of the lunch service the boss often asks us to anticipate the work for the next services. In reality, instead of having a break and time for myself, I work for the company, without any financial compensation. Even if I like it, it’s tiring sometimes.”[Christophe, 24 years old, cook in a commercial restaurant establishment]

The use of employees’ “free” time very often leads to tense relations because it is not always deducted from working time. Clearly, “working time has become an area of conflict or arrangement and an opportunity to define a power relationship that places the temporal dimension at the heart of social life” (Thoemmes and De Terssac 2006, p. 4). Manager-employee relations are characterised by the position of subordination of the employee to their employer (Supiot 1995), which here goes beyond professional schedules. Individuals are at the “boss’s disposal”, even in their non-working hours, to ensure the smooth running of the company. These forms of employee subjection are due to the small size of the restaurant establishments, the weakness of the unions and the pressure of the hotel culture, which binds the individual to others through a whole network of interactions (Whyte 1961; Retel 1965). Continuous work is implicitly taken for granted, the “break” being ignored either under the pressure of the employer who demands that his employees remain on the job, or under the pressure of the group which imposes the value system legitimising total commitment to work. The common will to ensure the smooth running of the establishment is strong and pushes employees to always be available. Working time becomes a time without formal limits.

4.1.3. Domestic Time

Yet, other older employees with family responsibilities take advantage of the “break” to do household and/or family chores. This is the time when children are at school and spouses are at work. Employees take advantage of their break to perform family tasks: car and house maintenance, administrative management of the household or any task related to the family and property environment. These household chores are done during the time the employees are alone.

“I have been working in gourmet restaurants for 12 years. I must admit that it is difficult to work evenings and weekends when my children and wife are at home. But when I am on duty, I take advantage of the “break” to take care of the house, to do small jobs. It also allows me to pick up my kids from school before going back to work,”[Mathieu, 46, cook in a gourmet restaurant].

“I like to have some free time in the afternoon between shifts because it allows me to manage my personal business. The time off gives me the opportunity to manage the house and take care of some of the family tasks. Little by little, my wife and I have organised all this around my job.”[Frédéric, 29, cook in a gourmet restaurant].

As the quote above shows, the cook absolutely wants to do these tasks outside of the times he shares with his family. Carrying out these household tasks during the “break” allows him to save time (Viard [2002] 2004) for the exclusive use of family leisure. The “break” is experienced here as a way of dealing with household time.

4.1.4. Time for Oneself

Thus, the “break” becomes leisure time, i.e., free time (Dumazedier 1988) outside the activities and constraints of paid employment and outside the concerns of the household. Employees take the time to engage in activities of personal well-being or social connection. In professional kitchens, employees also enjoy sharing this time with their colleagues.

“During the “break” I have time to relax or go to the beach with friends. I like this type of work because you feel that the day passes more quickly. At the end of the lunch shift, we hurry to change and go swimming. When the weather is bad, we take a nap or go for a drink and play table soccer or cards.”[Mathieu, 35 years old, cook in a commercial restaurant]

These exchanges during leisure time shape relationships of collective solidarity that also operate in professional practices. Individuals form friendships that go beyond the actual professional practice. They use this time as they wish and engage in sports, cultural or outdoor activities: visiting museums, swimming, running ... Any opportunity to take a break from work and relax is considered, so as to be in shape for the evening shift.

“I often ride my bike between two services. It keeps me in shape and helps me to get away from work. Sometimes some colleagues join me, but most of the time I ride 10 to 15 km a day alone. I have always done some physical exercise during the “break”.[Bruno, 36 years old, cook in a brasserie]

On a daily basis, some cooks approach the “break” as an “in-between” between constrained time and free time. Compulsory time, occupied by the employer, is a source of potential conflict. Time spent on “domestic” activities frees up time for family leisure, and time spent on personal activities is aimed at personal development (Dumazedier 1988).

4.2. Rules of the Continuous Working Time System

The continuous working time system’s gradual introduction offers catering employees a time framework involving new temporalities. In some cases, continuous working hours are chosen, but in other cases, employees are simply confronted with the changes in catering systems from break work to continuous working hours. As with the “break” system, continuous working time is also a model that leads to conflicts between employers and employees, especially when the legal daily working time is not respected.

4.2.1. An Organisational Choice against Individuals

The reconfiguration of food cost sector systems has resulted in some professional repositioning of existing staff. While this may be an opportunity for some to reconsider their careers and evolve by experiencing these changes as a real career opportunity, it is experienced as a constraint by others. Let’s take two examples showing that continuous working hours are experienced as an imposition: the first is the restructuring of a regional university hospital in a city of nearly 135,000 inhabitants, and the second is a public establishment of inter-municipal cooperation managing school canteens.

In the first case, the city has a central building and several other sites scattered over the municipal territory. Cooks work independently on each site and have developed strong social interactions, as they have organised their social life in the vicinity. The restructuring of the hospital catering system led to the centralisation of production in a new building and the reassignment of positions to meet the new requirements. Employees had to leave their sites to integrate the new structure, breaking with social routines, “built-in benefits” (Bernoux [2004] 2010) and just-in-time work patterns. The shift to continuous working time is thus experienced as a new imposed space from which the individual will begin to rebuild their social life.

“When it was decided that the hospital was going to be restructured, at first, I didn’t think that my job would change radically and that I would have to change location. Even though we were staying in the same city, it still disrupted my routine. I liked my old job because I had a lot of friends and after all, I had been working there for 12 years. I still remember that time even though I kept my job in the new organisation”[Luc, 52 years old, cook in hospital catering].

In the second example, the model is quite similar when a public institution decides to centralise production. Local agents are subject to political decisions and evolve towards new social temporalities as production is managed over one or more days before consumption. Adopting continuous working time means anticipating production flows and disconnecting production time from consumption time. Employees must face a new division of labour.

“I had been working in the same school for eight years before the city council and the urban community decided to set up a central kitchen 10 km away. I found it quite difficult at first because my whole life revolved around the school. So, I had to change my routine, because my new job was in the central kitchen. I thought about quitting, but I had no other choice. So, I got into the habit of driving my 10 km a day to work.”[Philippe, 47, school food service cook]

Cooks may experience the shift to all-day duty as a disruption of their time reference points because the changes often involve moving away from the workplace and losing social ties. Accustomed to the adrenaline rush associated with the close connection between production and consumption times, they experience these new forms of organisation as a reversal of the temporal patterns of the “break”, in which they have been inserted for many years. This new division of labour modifies their work rhythms and partly removes the pressure on them during service. But the previous organisation has shaped part of their occupational identity (Dubar and Tripier [1998] 2005) and has contributed to the construction of the temporal identity of their profession (Kanzari 2008). The growing role played by contract catering companies in the management of catering systems (Dondeyne 2001, 2002) has made occupational temporalities much clearer. The establishments are growing, the evaluation of working time is becoming more systematic, and in the large industrial groups, union pressure is increasing.

4.2.2. An Individual Choice for a Collective Organisation

Some cooks choose to work in a collective catering establishment after having been employed in commercial catering (Mériot 2002). They leave a professional world organised along the “break”, which they experienced as a porous work organisation carrying too many constraints, to move towards a world of all-day tasks likely to reinforce the boundaries between professional and private life (Tremblay and Genin 2009). School and company catering are thus perceived as allowing a better balance between the two social temporalities.

“I met my wife when I was doing seasonal work on the Mediterranean coast in a seafood restaurant. Being older, she wanted us to settle down to start a family. She said, “Look, if we’re going to have kids and enjoy them, you can’t keep working the way you’re working now. It was very difficult for me to choose between my passion for my work and the woman I loved. We now have two children, and I am happy to be able to share my evenings and vacations with them.[Hervé, cook in a food cost establishment]

Some also choose to advance their careers in corporate catering to be near their families in the late afternoon and on weekends. The balance they seek is obvious. Cooks are willing to work in very different commercial food service kitchens to have more time with their families. These types of positive choices have directed cooks towards food cost sector establishments where working all day is more common. Because they envision management positions without the constraints of commercial restaurants (evenings and weekends), these cooks choose to enter the food cost sector with the goal of attaining management positions (Dondeyne 2006), middle management positions as an area manager, or key account manager. These decisions are made early in one’s career or later by professionals with long careers in commercial food service management. Those employees seek similar positions, but in an all-day tenure setting rather than a “break” setting.

“The advantage of working in this school restaurant is that I get an early start, but I know my day ends at 4 p.m. Looking back on my years of working in commercial food service, I never knew when I would finish. A single service for lunch makes it a lot easier, as you know when you leave your workplace”[Camille, 33, cook in a school restaurant].

Occupational choices are complex to explain, however, the data also show that the size of organisations and their location influence individuals’ choices. Thus, the larger the food service systems (several hundred or thousands of meals per day), generally located in urban areas, the more we switch to continuous temporalities.

5. Discussion: The Future of the Time Configurations: All-Day Duty versus the Cultural Specificities of Food Intakes

5.1. The All-Day Rationalisation Trend

We have shown how the two work organisations have different meanings, as a whole and individually: the “break” can be extra time for the employer, or “domestic” time, or time for oneself; continuous work time can be imposed or chosen. Overall, the continuous day model is less restrictive and less subject to variable schedules. Schedules are predictable and work periods are more or less consistent with standard work periods. Employees have more control over their working time and are less subject to market or organisational pressure. Beyond the legal issues of paid vacations, negotiations take place regarding additional rest periods. On the contrary, in organisations operating according to the “break” scheme, we have noted frequent negotiations on questions of control over professional time: the “break” period, days off and atypical schedules. In the latter case, cooks are required to work evenings, nights, or weekends.7 Our research work has highlighted two situations. Atypical working hours are experienced as restrictive because they disrupt the whole social temporality. Consequently, they give rise to conflictual bargaining. Seniority in the organisation and alternation are used as criteria to make decisions about individual time constraints. But atypical schedules are also seen as an asset by some who appreciate the flexibility of work. They use it as a kind of power to control their social times. In this case, the law provides financial benefits that can sometimes make these schedules attractive. Like telephone operators in the 1950s and 1960s (Mahouche 2012), the social status of cooks is characterised by conflicts centred on employment, especially in centralised organisation, and by social conflict primarily centred on requests for control of working time (Bureau and Corsani 2012). These three items on the negotiation agenda (break, rest time, atypical hours) are the individual and collective translations8 set to define employees’ availability and establish their control over professional temporalities.

The forms of organisation have evolved in response to the hygiene constraints that govern the food industry, the economic pressure on the budgets of the food cost sector, and the evolution of meal production and distribution techniques.

In hospital and school catering, the emphasis is on health safety. Over time, due to the evolution of food chains, the evolution of food supply and food behaviours, the control of hygiene has almost become an “obsession”. This explains the process of centralisation at work in some catering structures. In France, this is certainly one of the arguments used to justify the restructuring of catering systems, which is mostly carried out by public bodies.9 These situations reflect the role played by public authorities in the evolution of catering systems. This new logic of hygiene has influenced the organisation of the production and distribution of meals.

Another change reveals the growing importance of economic rationality. The reduction of the legal working week in France since 1982 (from 40 to 39 h), followed by the introduction of the 35-h week, has reinforced the need to reorganise the commercial catering system (Afsa and Biscour 2004). Professionals in for-profit food service establishments are required to control the most burdensome operating costs: personnel and food. Their goal is to make a profit to sustain the business, but also, in the case of restaurant or hotel chains or large restaurant groups, to pay shareholders. Establishments in the food cost sector are faced with the same requirements when management has been entrusted to private catering companies.10

While the rationalisation logic differs according to the context, technical developments have also played a major role in the transformation of catering systems. Three technical developments illustrate this ongoing process: remote management, vacuum technology, and the so-called assembly kitchen. Thanks to an efficient cold chain and the development of cook-and-chill technology, restaurants can anticipate production several days before consumption. In the assembly kitchen, the increasing use of semi-finished and finished products, coupled with the restructuring of food supply chains (Vanhoutte 1982), have completely transformed the entire field of catering and reduced the processing time of food (Laporte 2010). This process, described as early as the mid-1980s (Poulain 1992; Poulain and Larrose [1986] 1995) and taken to its quintessential level, has played an important role in the food service industry. At the same time, vacuum technology reflects the evolution of food production methods by using an original cooking and preservation technique. Food products are sealed in airtight plastic bags, cooked without oxygen, vacuum-packed in a low-temperature water bath (or in a steam oven with moist heat) and/or preserved with the same technique. Rationalisation in the restaurant industry is to some extent similar to how industry was transformed in the late 19th century, simplifying tasks and “dehumanising” work (Friedman [1956] 1964). In some establishments, working time has also been assimilated to industrial time (Grossin 1996). Overall, the reduction of work and the desire to achieve productivity gains call into question the end of human work in professional kitchens (Rifkin 1998; Méda 1998). Whatever the rationalisation schemes, they have all led to the transformation of the profession of cook and its organisation, to the diversification of professional temporalities, and to the reinforcement of all day duty. The social status of cooks has thus been marked by conflicts of activities and social temporalities since the early 1980s.

5.2. The Resilience of the Break Model

What is the outlook for working hours for cooks in France? Does the rationalisation movement that is pushing the sector to work all day herald the end of the “break” and the associated risks? Nearly two thirds of cooks work in the restaurant and hotel industry according to the “break” model. For most of the occupational group, the synchronisation of meals divides their work activities into two sets of professional time. But the growth of school and corporate catering in France has generalised the pattern of all day duty, since in most cases food intake is concentrated at lunchtime. The recent development of out-of-home catering shows that the reduction of working hours, health and economic pressures and the rationalisation of models have prompted professionals to rethink their organisations. As a result, the full-day model has become more prevalent.

And yet, in France, there are good reasons to question the end of the “break” schedule for cooks. It seems that the cultural specificities of food intake tend to slow down the movement. Food intakes have been compared between France and the United Kingdom over the period 1961–2001, and the results show that intakes tend to be spread out over the day in the latter country, leading to a certain social desynchronisation of meals (Laporte and Poulain 2014). In France, there is a dual movement underway, tending towards a simplification of meals while maintaining schedules and a certain degree of synchronisation. There are also differences between British and French food consumption in terms of meal types and times. The consequences of these changes are even more important because more British people eat out of the home (21%, 2011) than French people (13.6%, 2006), which leads to less stable hours and increases the relative desynchronisation of meals in the UK. The relative meal synchronisation that exists in France doesn’t facilitate continuous working time, as customers stick to rather stable time slots. It is therefore quite predictable that the rationalisation of social times will evolve more slowly in France. The negative impact on working conditions and the resulting challenge of social synchronisation may well last longer in France than elsewhere. In summary, the collective synchronisation of food intake in France is obviously responsible for the greater desynchronisation of cooks’ social times.

6. Conclusions

Our article highlights the complex reality of the time configurations of French cooks. We have distinguished three levels: working time, social times, and temporalities. First, working time is based on long hours, often with fragmented schedules including (unpaid) overtime. Working evenings, weekends and holidays is a common phenomenon. Social times are under strain due to the weakening of the monopoly of work among social activities related to family, leisure, or rest. The reduction of working time has opened the way to new balances of social times. Temporalities refer to the variability of individual and subjective experience of time but are also closely linked to socialisation in professional institutions, schools, and workplaces. Long working hours are part of the professional ethos that cooks have acquired over the course of their careers. We analysed the temporal configurations of cooks by first following two main forms of organisation: the break schedule including a non-work period, usually from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m., and the continuous workday. We then showed that these two organisations can be perceived differently by cooks. The break schedule can be categorised as a configuration of unpaid overtime (1), of non-professional obligations (2), or as an opportunity for free time (3). The imposition of a continuous workday may negate the former sociability and time needs associated with the break schedule (4). Other cooks choose the continuous model, because it leaves more room and control for other activities that require a synchronised schedule (5). Finally, we discussed the future of these scheduling configurations. On the one hand, the trend towards capital-intensive forms of rationalisation of food production, distribution, and consumption seems to favour the continuous workday. On the other hand, French food consumption, which is still strongly synchronised around lunch and dinner, favours the dominant pattern of break times.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and J.T.; methodology, C.L.; J.T.; formal analysis, C.L. and J.T.; investigation, C.L.; resources, C.L. and J.T.; data curation, C.L. and J.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, C.L. and J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the confidentiality of the names of people and institutions that we have respected.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found from the Autor’s archives. You contact them if you need it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Thereafter we will use the plural form of social times to match the variety of activities with the plurality of times. In accordance with French employment surveys (DARES), we use the word “cook” here to refer to a category of employees that includes kitchen assistants, apprentices and multi-skilled restaurant workers as well as cooks and chef. |

| 2 | The length of time in the restaurants was based on the permits obtained for each establishment. Whenever possible, we focused on a long duration. The establishments studied (informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study) in the 2000–2003 period are not the same as those observed in 2017–2019. The first allowed us to describe the organizational forms of the restaurant industry in the early 2000s. The second allowed us to identify more contemporary forms of organization. The main interest for us was to compare two different contexts, at two different times, inorder to understand if one organizational model has developed more than another. |

| 3 | Dares, French National Reform Program Statistical annex on employment (Dares 2015). |

| 4 | However this work organisation varies when municipalities decide to pool resources by setting up inter-municipal cooperative public establishments to provide a catering service, centralise meal production in central kitchens (or central production units) and disconnect the production stage from distribution. In that case, cooks make meals which are only distributed the next day or the day after. |

| 5 | Insee, Répertoire des Entreprises et des Établissements (REE) (Company and Establishment Directory), Sirene Database, 2010. |

| 6 | Fifty-two percent of cooks work Saturdays and/or Sundays, Dares, 2012. |

| 7 | The casinos’ national collective agreement (2002); Cafeteria chains national collective agreement (1998); hotels, cafés restaurants national collective agreement (1997); outdoor accommodation national collective agreement (1993); fast food industry national collective agreement (1988); Paris and Ile de France three, four and four luxury star hotels regional collective agreement (1985); rail catering national collective agreement (1984); collective catering staff national collective agreement (1983); hotel national collective agreement (1975); catering staff national collective agreement (1970). |

| 8 | In September 2008, the municipality of Lannion, Côtes d’Armor, set up a central kitchen to distribute meals to 17 of the town’s public schools. Almost 1400 meals are produced and distributed by this new structure replacing outdated sites. The hygienic quality control of the meals was one of the main arguments in favour of setting up a new production site. |

| 9 | Sodexo, Compass and Elior are three main foodservice catering chains operating with concession contracts in the commercial and collective catering fields. |

| 10 | As early as 1974, the technique of the positive cold chain allowed cooked produce to be conserved more than three days after their production day. Conservation time significantly increased when the negative cold chain started being used. |

References

- Afsa, Cédric, and Pierre Biscour. 2004. L’évolution des rythmes de travail entre 1995 et 2001: Quel impact des 35 heures? Economie et Statistique 376: 173–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ast, Dorothée. 2012. Les Portraits Statistiques des Métiers 1982–2011. Available online: https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/pdf/synthese_stat_no_02_-_portraits_statistiques_des_metiers_1982-2011.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Aubry, François. 2012. Les Rythmes Contradictoires de L’aide-soignante. Conséquences sur la Santé au Travail de Rythmes Temporels Contradictoires, en France et au Québec. Temporalités. Available online: http://temporalites.revues.org/2237 (accessed on 12 November 2021).

- Aymard, Maurice, Claude Grignon, and Françoise Sabban. 1993. Le Temps de Manger: Alimentation, Emploi du Temps et Rythmes Sociaux. Paris: Ed. de la maison des sciences de l’homme. [Google Scholar]

- Barbier, Pascal. 2012. Travailler à contretemps. Vendre le soir, le dimanche, et les jours fériés dans les grands magasins. Temporalités 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, Pascal, Bernard Fusulier, and Julie Landour. 2020. L’articulation des temps sociaux: Une clé de lecture des enjeux sociaux contemporains. Les Politiques Sociales 2: 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Baudier, François, Michel Rotily, Geneviève Le Bihan, Marie-Pierre Janvrin, and Claude Michaud. 1996. Baromètre Santé Nutrition Adultes INPES. Available online: http://www.inpes.sante.fr/Barometres/Collection_Baro/nutrition96.asp (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Bernoux, Philippe. 2010. Sociologie du Changement Dans les Entreprises et les Organisations. Paris: Points, Coll. Points Essais. First published 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchareb, Rachid. 2012. Conflits autour d’une temporalité marchande dans les boutiques de réseaux. Temporalités 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffartigue, Paul, and Jean Bouteiller. 2006. Jongleuses en blouse blanche. La construction sociale des compétences temporelles chez les infirmières hospitalières. Temporalités 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffartigue, Paul, and Jean Bouteiller. 2012. Temps de Travail et temps de vie. Les Nouveaux Visages de la Disponibilité Temporelle. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Boulin, Jean-Yves, Michel Lallement, and Serge Volkoff. 2006. Introduction—Flexibilité, disponibilité et nouveaux cadres spatio-temporels de la vie quotidienne. Temporalités 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovagnet, François-Carlos. 2005. Employment in Hotels and Restaurants in the Enlarged EU Still Growing. Statistics in Focus, Theme 5—Industry, Trade and Services, Eurostat. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Bureau, Marie-Christine, and Antonella Corsani. 2012. La maîtrise du temps comme enjeu de lutte. Temporalités 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousin, Saskia, and Bertrand Réau. 2009. Sociologie du Tourisme. Paris: La Découverte, Coll. Repères. [Google Scholar]

- Dares. 2015. French National Reform Program Statistical Annex on Employment. Available online: https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/pdf/pnr_en__2015.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Dares. 2021. Portraits Statistiques des Métiers. Available online: https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/donnees/portraits-statistiques-des-metiers (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- De Saint Pol, Thibault. 2006. Le dîner des Français: Un synchronisme alimentaire qui se maintient. Economie et Statistiques 400: 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Terssac, Gilbert, Jens Thoemmes, and Anne Flautre. 2004. Régulation politique et Régulation d’usage dans le temps de Travail. Le Travail Humain 67: 135–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondeyne, Christel. 2001. Quelle prise de distance avec l’entreprise? Le cas d’une grande entreprise de restauration collective. In Cadres: La Grande Rupture. Edited by Paul Bouffartigue. Paris: La Découverte, Coll. Recherches, pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dondeyne, Christel. 2002. Professionnaliser le client: Le travail du marché dans une entreprise de restauration collective. Sociologie du Travail 44: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondeyne, Christel. 2006. L’évaluation de l’activité. Le cas des gérants de la restauration collective. In Sociologie du Travail et Activité. Edited by Alexandra Bidet. Toulouse: Octarès, Coll. Le travail en débats, pp. 221–33. [Google Scholar]

- Dubar, Claude. 2002. La socialisation. Construction des Identités Sociales et Professionnelles. Paris: Armand Colin. [Google Scholar]

- Dubar, Claude. 2004. Régimes de temporalités et mutation des temps sociaux. Temporalités. Revue de Sciences Sociales et Humaines 1: 117–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dubar, Claude, and Pierre Tripier. 2005. Sociologie des Professions. Paris: Armand Colin. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dumazedier, Jean. 1960. Problèmes actuels de la sociologie des loisir. Revue Internationale Des Sciences Sociales 4: 564–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dumazedier, Jean. 1988. La Révolution Culturelle du Temps Libre. 1968–1988. Paris: Méridiens-Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, É. 1998. Les Formes Elémentaires de la vie Religieuse: Le système totémique en Australie. Paris: PUF, Coll. Quadrige. First published 1912. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, Norbert. 1981. Qu’est-ce que la Sociologie? Paris: Pocket. First published 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2022. How Many Hours Do Europeans Work per Week? Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/fr/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20180125-1 (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Fellay, Angélique. 2009. Des heures sans valeur: Le travail des serveuses en horaire de jour. Nouvelles Questions Féministes 2: 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellay, Angélique. 2010. Les Serveuses/Serveurs de Restaurant: Étude Sociologique d’un “Petit Métier” de Service. Ph.D. dissertation, Université de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler, Claude, and Estelle Masson. 2008. Manger. Français, Européens, et Américains Face à L’alimentation. Paris: Odile Jacob. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Georges. 1964. Le travail en miettes. Paris: Gallimard. First published 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, Georges. 1960. Le loisir et la civilisation technicienne. Revue Internationale Des Sciences Sociales 4: 551–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fusulier, Bernard, and Chantal Nicole-Drancourt. 2019. Towards a multi-active society: Daring to imagine a new work-life regime. In Parental Leave and Beyond: Recent International Developments, Current Issues and Future Directions. Edited by Moss Peter, Ann-Zofie Duvander and Alison Koslowski. Bristol: University Press Scholarship Online, pp. 3315–31. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2078.1/223466 (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Glaude, Michel, and François De Singly. 1986. L’organisation domestique: Pouvoir et négociation. Economie et Statistique 187: 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossin, William. 1996. Pour une science des temps: Introduction à l’écologie temporelle. Toulouse: Octarès Editions, Coll. Travail. [Google Scholar]

- 2002. Baromètre Santé Nutrition 2002, INPES. Available online: http://www.inpes.sante.fr/Barometres/BaroNut2002/ouvrage/index.asp (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Haicault, Monique. 1984. La gestion ordinaire de la vie en deux. Sociologie du Travail 3: 268–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holm, Lotte. 2012. Pays nordiques. Les pays nordiques—Géographie. In Dictionnaire des Cultures Alimentaires. Edited by Jean-Pierre Poulain. Paris: PUF, pp. 985–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Jerry A., and Kathleen Gerson. 2001. Overworked Individuals or Overworked Families?: Explaining Trends in Work, Leisure, and Family Time. Work and Occupations 28: 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanzari, Ryad. 2008. Les sapeurs-pompiers, une Identité Temporelle de Métier. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Toulouse II-Le Mirail, Toulouse, France. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, Cyrille, and Jean-Pierre Poulain. 2014. Restauration au travail: Le rôle des dispositifs techniques dans la synchronisation de l’alimentation. France-Royaume Uni. Ethnologie Française XLIV: 861–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, Cyrille. 2010. Rationalisation des Systèmes de Restauration hors Foyer et Logiques d’action des Professeurs de Cuisine. Ph.D. dissertation, EHESS Paris, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, Cyrille. 2018a. Les enjeux de la restauration collective. In Dictionnaire des Cultures Alimentaires. Edited by Jean-Pierre Poulain. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, pp. 1051–57. First published 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, Cyrille. 2018b. La restauration collective. In Dictionnaire des Cultures Alimentaires. Edited by Jean-Pierre Poulain. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, pp. 1231–36. First published 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mahouche, Bruno. 2012. Conflits d’activités, conflits sociaux. Le cas des téléphonistes dans les années 1950 et 1960. Temporalités. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méda, Dominique. 1998. Le travail: Une Valeur en voie de Disparition. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Mériot, Sylvie Anne. 2002. Le Cuisinier Nostalgique: Entre Restaurant et Cantine. Paris: CNRS Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Monchatre, Sylvie. 2010. Êtes-vous Qualifié Pour Servir? Paris: La Dispute (Le genre du monde). [Google Scholar]

- Monchatre, Sylvie. 2011. Ce que l’évaluation fait au travail. Normalisation du client et mobilisation différentielle des collectifs dans les chaînes hôtelières. In Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales. Paris: Seuil, vol. 4, p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Murcott, Anne. 2012. Royaume-Uni. In Dictionnaire des Cultures Alimentaires. Edited by Jean-Pierre Poulain. Paris: PUF, pp. 1186–96. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, Jean-Pierre, and Gabriel Larrose. 1995. Traité d’ingénierie hôtelière. Conception et Organisation des Hôtels Restaurants et Collectivités. Paris: Editions Jacques Lanore. First published 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, Jean-Pierre, Romain Guignard, Claude Michaud, and Hélène Escalon. 2010. Les repas: Distribution journalière, structure, lieux et convivialité. In Baromètre Santé Nutrition INPES. Edited by Escalon Hélène, Claire Bossard and François Beck. Available online: http://www.inpes.sante.fr/nouveautes-editoriales/2010/barometre-sante-nutrition-2008.asp (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Poulain, Jean-Pierre. 1992. La Cuisine D’assemblage. Paris: BPI. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, Jean-Pierre. 2011. Sociologies de l’alimentation. Paris: PUF (Coll. Quadrige). First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, Jean-Pierre. 2012. Dictionnaire des Cultures Alimentaires. Paris: PUF. [Google Scholar]

- Poulain, Jean-Pierre. 2017. The Sociology of Food: Eating and the Place of Food in Society. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Retel, Olivier. 1965. Les gens de l’hôtellerie. Paris: Les éditions ouvrières (Coll. L’évolution de la vie sociale). [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud, Jean-Daniel. 1979. Conflit et régulation sociale: Esquisse d’une théorie de la régulation conjointe. Revue Française de Sociologie 20: 367–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaud, Jean-Daniel. 1988. Les régulations dans les organisations: Régulation de contrôle et régulation autonome. Revue Française de Sociologie 29: 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, Jeremy. 1998. The End of Work: The Decline of the Global Labor Force and the Dawn of the Post-Market Era. Journal of Leisure Research 30: 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, Haya, and Noah Lewin-Epstein. 2003. Time to work: A comparative Analysis of Preferences for working Hours. Work and Occupations 30: 302–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supiot, Alain. 1995. L’avenir d’un vieux couple: Travail et Sécurité sociale. Droit Social 9/10: 823–31. [Google Scholar]

- Thoemmes, Jens. 2013. Organizations and Working Time Standards: A Comparison of Negotiations in Europe. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thoemmes, Jens. 2019. Temps. In Les zones grises de l’emploi. Edited by Marie-Christine Bureau, Antonella Corsani, Olivier Giraud and Frédéric Rey. Buenos Aires: Teseo, pp. 523–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jens Thoemmes, and Gilbert De Terssac, directors. 2006, Les Temporalités Sociales: Repères Méthodologiques. Toulouse: Octares.

- Tremblay, Diane-Gabrielle, and Emilie Genin. 2009. Remodelage des temps et des espaces de travail chez les travailleurs indépendants de l’informatique: L’affrontement des effets de marchés et des préférences personnelles. Temporalités 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, Diane-Gabrielle. 2008. Conciliation Emploi-Famille et Temps Sociaux. Montréal: Presses de l’Université du Québec. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO, and ILO. 2014. Measuring Employment in the Tourism Industries–Guide with Best Practices. Madrid: World Tourism Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte, Jean-Marc. 1982. La Relation Formation-Emploi dans la Restauration. Travail Salarié Féminin, fin des Chefs-Cuisiniers et Nouvelles Pratiques Alimentaire. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Paris X, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Viard, Jean. 2004. Le sacre du temps libre. La société des 35 heures. La Tour d’Aigues: Editions de l’Aube. First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, Max. 1994. L’éthique Protestante et l’esprit du Capitalisme. Paris: Plon. First published 1905. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, William Foote. 1961. Men at Work. Homewood: Dorsey Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).