Abstract

In 2015, the United Nations and various countries committed to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The 17 goals revolve around 3 main axes: eradicating poverty, protecting the planet, and ensuring peace and prosperity for all people by 2030. These goals are integrated so that interventions in one area inevitably affect the others. Undoubtedly, this application involves developing competencies related to Prejudice, conflict resolution, and empowerment. Our research aims to analyse the knowledge and competency of university students undergoing specific training to facilitate the application of UNESCO’s objectives in their work performance, while incorporating human rights as a basis for all future actions. A total of 241 students from the University of Salamanca participated. The average age of the sample was 21.13 years; 76.8% were female, and 23.2% were male (22.41 ± 7.17 years old). The data collection protocol included questions related to knowledge of the Sustainable Development Goals and involving SDGs in their personal life and future profession, which were assessed using the empowerment Scale, the Conflictalk Scale, and the Subtle and Overt Bias Scale. Significant differences were found between SDGs knowledge and involvement with academic courses. There was a direct relationship between this knowledge and involvement with the control, esteem, and activism dimensions of the Empowerment Scale, cooperative from the Conflictalk Scale, and positive emotions had inverse relationships with threat–rejection, and traditional values from the prejudice scale. Our study found that students who are more engaged with the SDGs resolve conflicts cooperatively, foster community activism, and experience positive emotions, whereas students with aggressive conflict resolution are more Prejudiced.

1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations, together with different countries, committed to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In Spain, this commitment is reflected in the 2030 agenda or action plan to fulfil these commitments, considering different measures and the implementation timeframe (ONU 2015a, 2015b). The 17 goals revolve around 3 main axes: eradicating poverty, protecting the planet, and guaranteeing peace and prosperity for all people. These axes are integrated so that interventions in one area inevitably affect the others. In Table 1, the 17 SDGs are grouped into 5 thematic blocks of major importance for people and the planet.

Table 1.

Classification of SDGs according to thematic blocks.

Undoubtedly, achieving these goals means eradicating poverty and achieving sustainable development based on a sustainable, inclusive, and equitable economy. Promoting opportunities for all people, especially those with additional difficulties, helps in eliminating inequalities and promotes integrated and sustainable management of natural resources and ecosystems. This desired reality is part of a positive vision for the world and the capacity to meet SDG challenges.

We acknowledge that the commitment and interest of states manifest through signing agreements and their governance; however, it is impossible to achieve these objectives without the active participation of society. In their environment, each person, through their daily actions and together with others, encourage progress towards social and sustainable development. Regardless of their field of work, everyone is responsible for achieving the social commitment to jointly achieve this action plan, favouring people, the planet, and prosperity.

As argued above, it is not only social intervention professionals who are entrusted with this task; however, the role they play in their professional career is very relevant to human rights education, the fulfilment of SDGs, and achieving social change. We will call this task, as a whole, the culturalization of SDGs.

After analysing different interpretative frameworks from psychology fitting these claims, we recognise positive psychology as a facilitator in constructing a more satisfactory and positive reality from a scientific point of view. Focusing on an approach to human virtues and strengths that considers human potential, motivations, and capabilities—or studying people’s positive experiences, as Seligman described (Seligman 1999, [2002] 2005)—fosters positive individual characteristics that inspire their development, institutions, and/or programmes, with the aim to improve people’s quality of life. Interventions in this field aim to increase positive attitudes manifested in behaviours and thoughts, thereby achieving well-being and personal development (Chaves et al. 2017; Gil da Silva and Hofheinz 2020; Hendriks et al. 2019). According to Sheldon and King (2001), this approach allows intervention based on human potential, motivations, and positive capacities, including civic virtues that guide people’s sense of responsibility towards their communities to become better citizens (Contreras and Esguerra 2006; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000).

The whole field of education, particularly higher university education, is a promising platform to work on this intervention. University education trains future social intervention professionals based on critical thinking, facilitating a new world vision and creating real contributions. We agree with De la Calle et al. (2003), that education is a catalyst for development, since it is the instrument for building social awareness and progressing towards a fair and supportive world. Enhancing competencies and modifying them to be human-rights-based and SDG-oriented will require investing time in training students in social disciplines.

To initiate the intended changes, future professionals must internalise the three aforementioned competencies and values, and apply their knowledge about SDGs to their professional performance (Albareda-Tiana et al. 2019). This dedication requires specialised training through a proactive and participatory methodology that avoids rejecting these issues in their professional future. The proactivity required for these necessary skills involves knowledge about SDGs and developing positive attitudes. Understanding and knowing how to combat others downplaying their importance or are openly contrary to them is also important; therefore, prior to their vision, the perception and interpretation of these issues must be known (Aleixo et al. 2021).

Designing and planning the skillset and capacities required to develop the 17 objectives is complex and extensive. For this reason, our research team selected specific transversal processes: (1) empowerment; (2) conflict resolution; (3) Prejudice elimination.

The concept of empowerment can be understood as a social phenomenon or psychological variable. Suriá’s review (Suriá 2015) describes the concept of empowerment by different authors who treat situations similarly. Following Rappaport (1984) and Segado (2011), people have the potential to accomplish proposed goals by approaching life as a social opportunity—or, as indicated by Bejerholm and Björkman (2011) and Heritage and Dooris (2009)—as a set of personal attributes that manage to activate people towards achieving planned results and goals. According to Suriá (2015) and Musitu and Buelga (2004), the relationship between SDGs and empowerment is logical, and as Rappaport (1981) describes, strengthens the control and dominion acquired by individuals, their communities, and organisations, from autonomy and critical thinking. These values are necessary, in the researchers’ opinion, to internalise and implement SDGs in the field of social intervention.

Conflict resolution is fundamental and necessary for achieving SDGs, as it transversally influences the 17 SDGs by reducing violence, specifically SDG 16—peace, justice, and strong institutions. The capacity for different actors to achieve a satisfactory resolution must be considered. Garaigordobil et al. (2016) claim that conflict resolution depends on the way in which it is managed. The solution can be positive and constructive if resolved properly; on the contrary, it generates tensions and Prejudices if the affected parties are not involved. It is necessary to identify the attitude students have towards conflict to progress the so-called peace culture. Adequate conflict management skills must be acquired to advance conflict management. This project includes conflict resolution in teaching programmes, both theory and practice.

Challenges for SDGs include community inclusion and eliminating discrimination. While all the goals, in a cross-cutting manner, work against all forms and manifestations of discrimination, SDG 5—Gender Equality—and SDG 10—Reducing Inequalities—focus specifically on these goals.

In this study, we followed the same reasoning provided for empowerment and conflict resolution, which highlights the need to identify Prejudices in the students to plan actions aimed at changing attitudes, through adequately programmed training. Our research aimed to analyse SDG knowledge, the degree of development for the competencies described, and their link to students at the University of Salamanca. We also designed specific training to facilitate the application of UNESCO goals in future work performance, incorporating the human rights perspective to develop all actions. This training is part of a teaching innovation project in which teaching methodologies for developing competencies and generating attitudes to implement SDGs in the professional sphere are proposed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instruments

The students responded to an ad hoc questionnaire for assessing knowledge of SDGs and their applicability in students’ lives, as well as six true or false questions related to SDG information, designed so that students could discriminate between “yes” and “no”. In addition, a Likert scale (1–6) was used to evaluate the degree of SDG application in daily life, academic life, and future profession. In addition to the knowledge obtained in university, the following were also assessed:

- (1)

- The Empowerment Scale (Empowerment) by Rogers et al. (1997). We used the adapted version of this work by Suriá (2015). It comprises 28 items measured on a Likert scale of 4 categories (1 = highly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree) that assess aspects of the students’ perceived capacity in decision making. The theoretical and factorial structure of the questionnaire groups the 28 items into 5 latent dimensions: self-esteem/self-efficacy (esteem—items 5, 6, 9, 12, 14, 18, 19, 24, and 26), power/empowerment (power—items 7, 8, 10, 16, 17, 21, 22, and 23), community activism/autonomy (activism—items 3, 11, 20, 25, 27, and 28), optimism for/control over the future (control—items 1, 2, 13, and 27), and appropriate anger (anger; items 4, 7, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 25, 27, and 28).

- (2)

- The Spanish adaptation of Kimsey and Fuller (2003) self-reported scale—“Conflictalk”, by Garaigordobil et al. (2016)—consists of 18 items, measured on a 5-point Likert scale and structured around 3 latent dimensions: cooperative (cooperative—items 3, 5, 7, 11, 12, and 17), avoidant (passive—items 2, 4, 6, 13, 14, and 15), and aggressive (aggressive—items 1, 8, 9, 10, 16, and 18) resolution (passive—items 1, 8, 9, 10, 16 and 18).

- (3)

- The Spanish adaptation of the Pettigrew and Meertens (1995) Subtle and Overt Bias Scale consists of 20 items rated on a 6-level Likert scale measuring 2 latent subscales—the blatant and subtle Prejudice Scale—which assesses 2 and 3 latent dimensions, respectively. The former consists of 6 items assessing the latent dimension of threat/rejection (threat and rejection—items 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 14) and 4 items measuring close relationships (anti-intimacy—items 3, 12, 13, and 18). The subtle Prejudice subscale comprises 10 items structured around 3 latent dimensions, which include the traditional values dimension (traditional values—items 1, 2, 10, and 17), cultural differences (cultural differences—items 5, 11, 15, and 16), and positive emotions (positive emotions—items 19 and 20).

2.2. Procedure

Ten teachers from the University of Salamanca and members of the teaching innovation project ID2020/046 granted us access to participants of the same university. The program was approved by a responsible committee at the University of Salamanca and presented in an annual call 5454/5545. Its main objective was to train students in different degrees of SDGs and human rights. For this reason, no ethical approval or specific consent procedures were necessary for this study, as the university’s teaching innovation committee previously evaluated it.

The teachers involved in the project teach social sciences, law, and education at the academic institution. First, the research team designed the evaluation protocol considering the intended objectives of the research. The protocol was then adapted to a Google questionnaire to facilitate dissemination to the teaching staff and students. The teachers in charge explained participation in the research to their students and informed consent beforehand.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The scales’ internal consistency and dimensions were assessed through Cronbach’s α reliability coefficient. This procedure was accompanied by McDonald’s ω and greatest lower bound (GLB and GLBFA) coefficients, appropriate in the case of items measured on a Likert scale, and asymmetric distributions (Vega-Hernández et al. 2017). The factor structure of the questionnaires was examined through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the maximum likelihood method. The fit for each of the three models was assessed using several indicators: RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation), where the model fit is considered adequate with a value of <0.08, SRMR (standardized root mean square residual), whose acceptable fit value is 0.08, goodness-of-fit Index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), relative fit index (RFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) coefficients, with values close to 1 considered adequate.

The university students’ scores for each of the latent dimensions in the three scales were calculated. These scores were obtained from the sum of the corresponding items while considering the appropriate direction of the items and inverting those items posed inversely.

In addition, an index with knowledge about SDGs was obtained for each of the students. This index was calculated from individuals’ correct answers to the following items: “The target date for achieving Sustainable Development Goals is 2025“, “SDGs have a cross-cutting principle, i.e., different SDGs are correlated”, “The motto of SDGs is ‘leave no one behind’”, “Improving HAPPINESS is one of the most important SDGs”, “The implementation of SDGs is exclusively the responsibility of public administrations”, and “SDGs are related to human rights”. Thus, each student had a score from 0 to 6 points (from not scoring any item correctly to scoring all the items correctly).

The analysis of quantitative variables was conducted using measures of central tendency and appropriate deviation according to the data distribution (mean and standard deviation for symmetrically distributed variables and the median and interquartile ranges for asymmetrically distributed variables). Between-group differences in latent dimension scores were examined using the corresponding parametric or non-parametric test for two groups (Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test) or more than two groups (ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis). Pairwise comparisons of groups were studied using Bonferroni post hoc tests where significant overall differences were found. Qualitative variables were analysed using frequencies and percentages.

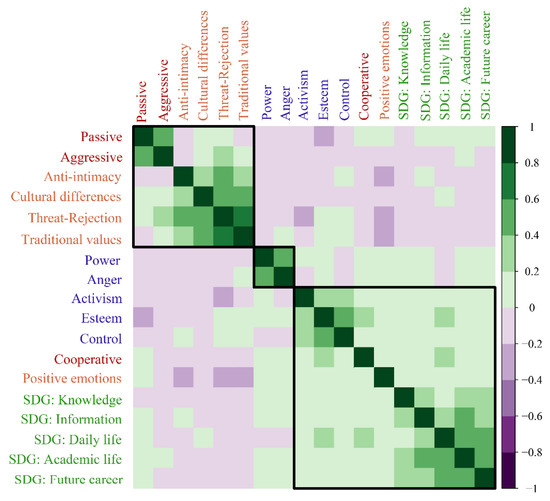

The relationships between knowledge and opinion about SDGs and the latent dimensions of the questionnaires were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficients between pairs of variables. These coefficients were plotted on a correlation graph with a colour scale to differentiate between direct and inverse, and weak and strong relationships between variables. In addition, the variables were grouped using Ward’s hierarchical clustering according to relationships between them.

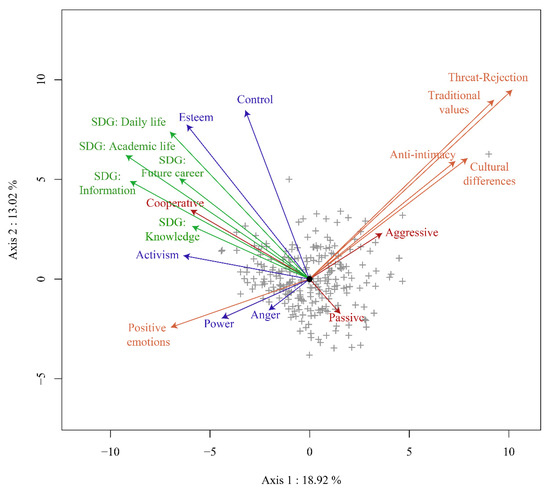

A multivariate analysis was conducted to characterise these relationships using the HJ-Biplot technique (Galindo 1986). The HJ-Biplot is a multivariate data visualisation tool that allows the joint graphical representation of the rows (students) and variables (items/dimensions) in a data matrix. Just as a scatter plot examines the relationship between two variables, the HJ-Biplot interprets relationships between more than two variables and their implications for the behaviour of individuals in the sample. The HJ-Biplot was used in this study to understand the university students’ behaviour according to the scale dimensions and relationship to their opinion and knowledge about SDGs. Therefore, this technique represents the students, the scale dimensions, opinion items, and knowledge of SDGs in the same scatter plot. Students are plotted as dots and the items associated with SDGs and scale dimensions as arrows on the graph. The relationships between them can be derived by the indications below:

- ○

- Variability of items and dimensions: The arrow length shows the variability of the variables represented. The longer the length, the greater the discrepancy in each opinion/dimension.

- ○

- Similarity between individuals: Students represented by close dots on the graph are students who scored similarly on SDG items and presented a similar profile for the dimensions of the questionnaires used.

- ○

- Correlation between items and dimensions: The relationship between SDG knowledge, opinion items, and the three scales’ latent dimensions can be examined. It is necessary to study the angles that comprise the arrows representing them. Thus, items and/or dimensions presenting angles of <90° are variables with direct and strong relationships shown by how the small this angle is. This correlation implies that students with higher scores on one variable also have higher scores on the other. Conversely, angles >90° imply inverse relationships between these items/dimensions. The closer the corresponding angle is to 180°, the stronger the relationship. Thus, students with higher scores on one variable will have lower scores on the other. Finally, angles closer to 90° imply independence of variables.

- ○

- Student profiling: The behaviour of a set of students was characterised according to their scores on different scales and items considered. It is necessary to project each of the points (students) perpendicularly on the arrows (item/dimension), reproducing the order of the students’ scores on that item/dimension. The closer the point is to the tip of the arrow, the higher that student’s score on the corresponding item/dimension.

Data analysis was conducted using the free software R (R Core Team 2021). The biplotbootGUI library was used to conduct the HJ-Biplot analysis (Nieto-Librero et al. 2021).

3. Results

3.1. Psychometric Properties of the Scales

The reliability measures of each scale and its dimensions are shown in Table 2. The internal consistency of the different dimensions was acceptable, except for the control and anger dimensions (the Empowerment Scale) and positive emotions (the prejudice scale), where the internal consistency values were low. These lower values may be due to the number of items that comprise each dimension, which should be considered when interpreting results associated with the dimensions.

Table 2.

Internal consistency of the Empowerment, Conflictalk, and prejudice scales, and their dimensions.

The CFA scale results are shown in Table 3. The Empowerment (RMSEA = 0.060, SRMR = 0.070), Conflictalk (RMSEA = 0.063, SRMR = 0.072), and prejudice (RMSEA = 0.077, SRMR = 0.074) scales showed adequate model fit.

Table 3.

Fit indices of AFC factor models for the Empowerment, Conflictalk, and prejudice scales.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive analysis of the three scales and each of their latent dimensions are shown in Supplementary Tables S1–S3.

3.3. Influence of Sociodemographic Variables on Knowledge and Consideration of the SDGs

The possible influence of variables including gender, nationality, academic year, and sexual orientation was studied in the following items: “I consider SDGs very present in my daily life” (SDG: Daily life) “I consider SDGs very present in my academic life” (SDG: Academic life)”, “I consider SDGs very present in my future career” (SDG: future career), “In class, we were provided information about SDGs” (SDG: Information), and “Index of knowledge about SDGs” (SDG: Knowledge).

Statistically significant differences were found for all items with respect to the students’ current academic year. In particular, statistically significant differences were found in the SDG item Daily life according to the students’ current academic year (p = 0.020), specifically between first- and fourth-year students (p = 0.028). Fourth-year students considered SDGs as more present in their daily lives (Me = 3, P25 = 3, P75 = 4) than first-year students (Me = 3, P25 = 2, P75 = 3). Statistically significant differences were also found in the STG Academic life according to the students’ current academic year (p < 0.001), specifically between first- and third-year students (p < 0.001), fourth-year students (p < 0.001), and master’s degree students (p = 0.006). Differences were also found between students in the second and third year (p = 0.012), fourth year (p = 0.032), and master’s degree (0.040). In general, students in higher grades consider SDGs as more present in their academic lives (third: Me = 4, P25 = 3, P75 = 4; fourth: Me = 3, P25 = 3, P75 = 4; master: Me = 4, P25 = 4, P75 = 5) than students in lower grades (first: Me = 3, P25 = 2, P75 = 3; second: Me = 2, P25 = 2, P75 = 3).

As for the SDG item Knowledge, significant overall differences were found according to the students’ year (p = 0.042), whereas no significant differences were found by group pairs in the post hoc tests. Overall, the knowledge scores of students in all grades were high, particularly in higher grades such as third, fourth, UD, and master’s degree (first: Me = 4, P25 = 4, P75 = 5; second: Me = 4, P25 = 4, P75 = 5; third: Me = 5, P25 = 4, P75 = 6; fourth: Me = 5, P25 = 4, P75 = 5; UD: Me = 5, P25 = 5, P75 = 6; master: Me = 5, P25 = 4, P75 = 5).

Students from different grades had significantly different opinions on the SDG future career (p < 0.001), particularly between first- and third-year students (p = 0.006) and first- and fourth-year students (p < 0.001). Third- and fourth-year students anticipate SDGs in their future careers (third year: Me = 4, P25 = 3, P75 = 5; fourth year: Me = 4, P25 = 3, P75 = 5) more than first-year students (Me = 3, P25 = 3, P75 = 4).

Differences were found in the SDG Academic life according to the education of the student’s father (p = 0.026), whereas no significant differences were found in pairwise comparisons of groups. In the student sample, higher scores were found for students with parents with doctoral degrees.

Highly significant differences were found in students’ opinions on Information (p = 0.001), according to students’ living situation in Salamanca and their current academic year (p < 0.001). Thus, students who lived alone felt that they received more information about SDGs in class (Me = 3, P25 = 2, P75 = 4) than those living in a residence hall (p < 0.001, Me = 2, P25 = 1, P75 = 3) or shared flat (p = 0.043, Me = 2, P25 = 1, P75 = 3). On the other hand, there were differences in their opinion about information received between first-year students (Me = 2, P25 = 1, P75 = 3) and third-year students (p = 0.002, Me = 3, P25 = 2, P75 = 5), fourth-year students (p = 0.002, Me = 3, P25 = 2, P75 = 5), fourth-year students (0. 036, Me = 3, P25 = 1, P75 = 4), and master’s students (0.013, Me = 5, P25 = 3, P75 = 5). Master’s students felt they received more information, followed by third- and fourth-year students, and finally, first-year students.

No significant differences in the scores for any item were found according to students’ gender, nationality, sexual orientation, mother’s education, father’s profession, and whom they live with at their place of residence.

3.4. Relationship between Knowledge and Opinion about SDGs and Latent Dimensions

First, the pairwise relationships between SDG knowledge, opinion items, and latent dimensions were studied. A graphical representation of the correlation matrix is shown in Figure 1, where the variables are grouped according to the relationships between them using Ward’s hierarchical clustering. A green and purple colour scale highlights direct and inverse relationships between each pair of variables, respectively. In turn, the strength of the relationships is captured by the intensity of the colour. It is worth noting that the SDG knowledge and opinion items show direct relationships with the control, esteem, and activism dimensions of the Empowerment Scale, cooperative of the Conflictalk Scale, positive emotions of the Prejudice Scale, and inverse relationships with threat–rejection and traditional Values of the Prejudice Scale. Different colours are used to differentiate each scale: SDG opinion and knowledge (green), empowerment (indigo), Conflictalk (red), and Prejudice (orange).

Figure 1.

Correlation matrix between SDG opinion and knowledge items and latent dimensions of the Empowerment, Conflictalk, and Prejudice Scales. Note: green: direct correlations; purple: inverse correlations.

An HJ-Biplot analysis was conducted on the standardised data matrix to complement the characterisation of these relationships, retaining 2 principal components that absorbed 31.94% of the data’s total variability. The factorial plane of components 1–2 is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Factorial plane of the HJ-Biplot components 1–2. Colours used to highlight each scale: SDG opinion and knowledge (green), Empowerment (indigo), Conflictalk (red), and Prejudice (orange). Note: own elaboration.

The HJ-Biplot interprets relationships between variables and allows us to study the association between latent dimensions and SDG attitude items.

As for the Conflictalk Scale, the aggressive dimension is independent of the cooperative and passive dimensions, whereas the cooperative and passive dimensions are inverse (i.e., students with higher cooperative resolution scores have lower passive resolution scores and vice versa).

The power and anger dimensions of the Empowerment Scale are directly and strongly related and independent of the esteem and control dimensions. On the other hand, activism is directly related to the previous four dimensions; however, these relationships are not very strong. As for SDG measurement variables, SDG knowledge and consideration items are highly related.

From the relationships between the different scale dimensions and knowledge/opinion of SDGs, it is worth noting that students with cooperative resolution have more knowledge and a better opinion about valued aspects of SDGs. These students were also characterized by higher esteem and control scores, especially concerning the SDG Knowledge index (SDG: Knowledge). It is worth highlighting its strong relationship with the activism and cooperative dimensions; university students with greater knowledge of SDGs have higher scores for cooperative resolution and community activism. Finally, the passive dimension is inversely related to variables related to SDGs. Thus, students with higher passive resolve have lower knowledge and opinions of SDGs.

The different dimensions of the Prejudice Scale are shown to be independent of opinion and knowledge of the SDGs, except for the positive emotions dimension, which is directly but not strongly related. Furthermore, the latter latent dimension is inversely related to the other dimensions of the Prejudice Scale. Furthermore, students with a higher aggressive resolution had higher scores in different dimensions of the Prejudice Scale, except for the positive emotions dimension, which was inversely related.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Since the adoption of SDGs, the university framework has become an ally for implementing SDG-related measures for various reasons. SDGs aim to transform the world and, therefore, society. In this challenge, universities play an important role in training advanced human capital, generating knowledge, contributing to equity, and progressing development by responding to social demands (Rodríguez-Ponce 2009).

A university’s capacity to build a culture around SDGs is more than proven; they have previously participated in other less ambitious challenges that have played, and continue to play, a fundamental role in society. The so-called “knowledge transfer” is part of a university’s purpose, being one of the means to achieve the SDG of culturalization.

The university community has started engaging in the implementation of SDGs. Our research shows that students in higher education are more knowledgeable about SDGs than those in the earlier stages of their studies because they received training during their academic experience. Regarding the “integration” that university students perceive in their daily or future professional life, students in advanced courses consider themselves present in their daily life and future profession.

Our results show that students knowledgeable about SDGs and "more receptive" to their claims show a better relationship with optimism/control for the future, self-esteem/self-efficacy, and community activism. They also allow us to identify the development level of the three essential competencies for implementing these goals. Regarding conflict resolution, a cooperative approach stands out, implying interest in the cause of the conflict, identifying the problem in collaboration with others, and focusing on a unified solution. In terms of prejudices, they show positive emotions.

According to Ramos-Vidal and Maya-Jariego (2014), the psychological sense of community, citizen participation, and empowerment are fundamental concepts for implementing strategies to improve others’ quality of life. As our results show, students consider SDGs an important instrument to them because they were designed to foster a psychological sense of community and participation, according to Chavis and Wandersman (1990). These authors considered the involvement of people from meso-social environments with participation dynamics and community empowerment as factors for encouraging participation and a sense of community. According to Perkins and Zimmerman (1995), psychological empowerment is interrelated with community involvement. Our research results coincided with those of Zimmerman (1995), in that psychological empowerment has interpersonal, interactive, and behavioural components. This relationship includes a greater belief in gaining knowledge and participating in their profession, especially for students who obtain higher scores with their future, self-efficacy, and community activism in mind.

These results suggest that student groups who relate empowerment with knowledge and include SDGs in their profession and daily life are more involved in community transformation. McMillan (2011) concluded that people who acquire greater control of their environment feel more independent and consider themselves responsible for their community, which are necessary aspects for bringing about change.

Conflict resolution is very present in SDGs, since the fulfilment of each one involves making decisions as situations arise. In our study, the collaborative resolution strategy influences student involvement in the knowledge and application of SDGs; in turn, this confirms that students with a passive conflict resolution strategy have less knowledge and a poorer opinion of SDGs. The cooperative conflict resolution strategy implies greater empathy and non-acceptance of aggressive and violent behaviour (Garaigordobil 2012, 2017).

Different studies have addressed the relationship between empathy and promoters of prosocial behaviours (Álvarez et al. 2010; Mestre et al. 2002). The conclusions of Luna-Bernal (2017) study are relevant to ours regarding the study of empathy and conflict management. In this case, their results showed that the problem-focused style, i.e., the cooperative strategy, has a positive relationship with global empathy. This finding is consistent with Davis (1980, 1983, 1996) definition of multidimensional empathy as perspective-taking, idealist, and empathic, with some personal discomfort.

Conflict resolution strategies oriented towards collaborative strategies influence greater internalisation of SDGs.

Regarding prejudice, our research shows a distinction between those with knowledge of SDGs and others with subtle and overt prejudice. However, it has been observed that students with aggressive conflict resolution have high scores on the Prejudice Scale.

It is necessary to further investigate the relationship between prejudice and SDG literacy. In our case, this distinction may be due to dissonance between SDGs’ approaches and prejudiced attitudes or their cross-cutting perspective, which implies the equality of all people and defending human rights—issues that are incompatible with prejudice, both explicitly and subtly.

Our study’s conclusions facilitated a series of seminars developed as a pilot experience for social work and criminology students. The content of this series included the following: knowledge of SDGs, managing emotions and problem-solving skills, empathy and decision making, and decisions related to SDGs and the immediate environment. The results encouraged us to continue working in the immediate future with these and other competencies linked to SDGs. There is still a significant amount of research needed; however, this study guides us on working in a transversal way and training future professionals to achieve our goals: eradicating poverty, protecting the planet, and guaranteeing peace and prosperity for all people.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci11020067/s1, Tables S1–S3.

Author Contributions

E.M.P.-V., A.Y., and R.G.-O. proposed the research design and theoretical framework supporting this work. They also conducted the literature review and distributed the data collection in classrooms. The professors overseeing the projection, design, and statistical analysis of this project were A.B.N.-L. and N.G.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has benefited from the support of the “Diagnosis and Evaluation of the compliance by the Spanish State of the Global Compact on Migration from a Gender Perspective” project, funded within the framework of the R + D+ i Program of the Ministry of Science and Innovation of the Government of Spain. Call 2019 (Ref. PID2019-106159RB-100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Within the different actions of the aforementioned research project, 10 professors of the research group apply and compete in the annual framework of educational innovation projects of the University of Salamanca in order to raise awareness and train students of different degrees in SDGs and Human Rights. This action, reviewed by the institution itself, was approved by the responsible commission of the University of Salamanca (teaching project ID2020/046 of the Usal, annual call 5454/554).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the dataset remains for exclusive use by the authors due to participant privacy and informed consent. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the author of correspondence.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the support of the recognised research group Public Policies in Defence of Inclusion, Diversity and Gender (GIR DIVERSITAS) for the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Albareda-Tiana, Sílvia, Esther García-González, Rocío Jiménez-Fontana, and Carmen Solís-Espallargas. 2019. Implementing Pedagogical Approaches for ESD in Initial Teacher Training at Spanish Universities. Sustainability 11: 4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixo, Ana Marta, Susana Leal, and Ulisses M. Azeiteiro. 2021. Higher Education Students’ Perceptions of Sustainable Development in Portugal. Journal of Cleaner Production 327: 129429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, Percy Cabrera, Marcela Carrasco Gutiérrez, and Jennifer Fustos Mutis. 2010. Relación de la empatía y género en la conducta prosocial y agresiva, en adolescentes de distintos tipos de establecimientos educacionales. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología 3: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejerholm, Ulrika, and Tommy Björkman. 2011. Empowerment in Supported Employment Research and Practice: Is it relevant? The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 57: 588–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, Covadonga, Irene Lopez-Gomez, Gonzalo Hervas, and Carmelo Vazquez. 2017. A Comparative Study on the Efficacy of a Positive Psychology Intervention and a Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Clinical Depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research 41: 417–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavis, David M., and Abraham Wandersman. 1990. Sense of Community in the Urban Environment: A Catalyst for Participation and Community Development. American Journal of Community Psychology 18: 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Francoise, and Gustavo Esguerra. 2006. Psicología positiva: Una nueva perspectiva en psicología. Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología 2: 311–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Mark H. 1980. A Multidimensional Approach to Individual Differences in Empathy. Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology 10: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Mark H. 1983. Measuring Individual Differences in Empathy: Evidence for A Multidimensional Approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44: 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Mark H. 1996. Empathy. A Social Psychological Approach. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- De la Calle, Velasco María Jesús, Martín Rodríguez Rojo, Elena Ruiz Ruiz, and Luis Torrego Egido. 2003. La Educación para el Desarrollo en el Marco Educativo. Valladolid: Departamento de Didáctica y Organización Escolar, Facultad de Educación, Universidad de Valladolid. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo, María Purificación. 1986. An Alternative for Simultaneous Representation: HJ-Biplot. Questiió: Quaderns d’Estadística, Sistemes, Informatica I Investigació Operativa 10: 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil, Maite. 2012. Resolución de conflictos cooperativa durante la adolescencia: Relaciones con variables cognitivo-conductuales y predictores. Infancia y Aprendizaje 35: 151–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, Maite, Juan M. Machimbarrena, and Carmen Maganto. 2016. Adaptación española de un instrumento para evaluar la resolución de conflictos (Conflicktalk): Datos psicométricos de fiabilidad y validez. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes 3: 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Garaigordobil, Maite. 2017. Conducta antisocial: Conexión con bullying/cyberbullying y estrategias de resolución de conflictos. Psychosocial Intervention 26: 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil da Silva, Doralúcia, and Claudia Hofheinz. 2020. Positive Psychology Intervention for Families of Hospitalized Children. Psychology of Health 30: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, Tom, Meg A Warren, Marijke Schotanus-Dijkstra, Aabidien Hassankhan, Tobi Graafsma, Ernst Bohlmeijer, and Joop de Jong. 2019. How WEIRD are Positive Psychology Interventions? A Bibliometric Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials on the Science of Well-Being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 14: 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heritage, Zoe, and Mark Dooris. 2009. Community Participation and Empowerment in Healthy Cities. Health Promotion International 24: 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimsey, William D., and Rex M. Fuller. 2003. Conflictalk: An Instrument for Measuring Youth and Adolescent Conflict Management Message Styles. Conflict Resolution Quarterly 21: 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Bernal, Alejandro César Antonio. 2017. Relación entre estilos de manejo de conflictos y empatía multidimensional en adolescentes bachilleres. RICSH Revista Iberoamericana de las Ciencias Sociales y Humanísticas 6: 80–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McMillan, David W. 2011. Sense of Community, Theory Not A Value: A Response to Nowell And Boyd. Journal of Community Psychology 39: 507–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, Vicenta, Paula Samper García, and María Dolores Frias Navarro. 2002. Procesos cognitivos y emocionales predictores de la conducta prosocial y agresiva: La empatía como factor modulador. Psicothema 14: 227–32. Available online: http://www.psicothema.com/pdf/713.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Musitu, Gonzalo, and Sonia Buelga. 2004. Desarrollo Comunitario y Potenciación. Introducción a la Psicología Comunitaria 10: 167–93. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Librero, Ana Belén, Purificación Galindo Villardón, and Adelaide Freitas. 2021. BiplotbootGUI: Bootstrap on Classical Biplots and Clustering Disjoint Biplot. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=biplotbootGUI (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Organización de Naciones Unidas (ONU) Asamblea General. 2015a. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/2015/09/la-asamblea-general-adopta-la-agenda-2030-para-el-desarrollo-sostenible/ (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Organización de Naciones Unidas (ONU). 2015b. Transformar Nuestro Mundo: La Agenda 2030 Para El Desarrollo Sostenible. Available online: https://www.agenda2030.gob.es/recursos/docs/APROBACION_AGENDA_2030.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Perkins, Douglas D., and Marc A. Zimmerman. 1995. Empowerment Theory, Research and Application. American Journal of Community Psychology 23: 569–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Roel W. Meertens. 1995. Subtle and Blatant Prejudice in Western Europe. European Journal of Social Psychology 25: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Ramos-Vidal, Ignacio, and Isidro Maya-Jariego. 2014. Sentido de comunidad, empoderamiento psicológico y participación ciudadana en trabajadores de organizaciones culturales. Psychosocial Intervention 23: 169–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, Julian. 1981. In Praise of Paradox: A Social Policy of Empowerment over Prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology 9: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, Julian. 1984. Studies in Empowerment: Introduction to the Issue. Prevention in Human Services 3: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ponce, Emilio. 2009. El rol de las universidades en la sociedad del conocimiento y en la era de la globalización: Evidencia desde Chile. Interciencia 34: 824–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. Sally, Judi Chamberlin, and Marsha Langer Ellison. 1997. A Consumer-Constructed Scale to Measure Empowerment among Users of Mental Health Services. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) 48: 1042–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segado, Sagrario. 2011. Nuevas Tendencias en Trabajo Social Con Familias: Una Propuesta Para la Práctica Desde el Empowerment. Rosario: Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, Martin E. P. 1999. The president’s address. APA.1998. Annual Report. American Psychologist 54: 559–62. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, Martin E. P. 2005. La Auténtica Felicidad. Traducido por Merce Diago y Abel Debrito. Colombia: Imprelibros, S.A. First published 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, Martin E. P., and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. 2000. Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist 55: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Kennon M., and Laura King. 2001. Why positive psychology is necessary. American Psychologist 56: 216–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriá, Raquel. 2015. Factores asociados al empoderamiento en personas con lesión medular tras un accidente de tráfico. Gaceta Sanitaria 29: 172–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Hernández, María C., M. Carmen Patino-Alonso, Rosario Cabello, M. Purificación Galindo-Villardón, and Pablo Fernández-Berrocal4. 2017. Perceived emotional intelligence and learning strategies in Spanish university students: A new perspective from a canonical non-symmetrical correspondence analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, Marc A. 1995. Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology 23: 581–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).