Abstract

The well-being of children and non-human animals (subsequently referred to as animals) is often intertwined. Communities are unlikely to be able to best protect humans from abuse and harm unless they are working to ensure the safety of animals who reside there as well. This study is the first to utilize U.S. animal control report data and narratives to explore how children are involved in cases of animal cruelty. Children engage in abusive acts toward animals, alone, or along with peers and/or adults. Children were found to inflict abuse most often with their hands or feet as opposed to with a weapon or other object. A total of 85% of animal cruelty perpetrated by children was toward a dog or cat. Key differences between how children are involved in acts of cruelty to companion animals compared with acts involving wild animals are described and warrant further study. The cases of animal abuse or neglect reported by children were among the most severe in the study, and often involved an adult perpetrator known to the child. Neighbors rarely report child abuse or intimate partner violence in the United States, but 89% of the animal cruelty cases involving children in this study were reported by a neighbor or passerby. Although children involved in reports as a perpetrator or reporter were most often in early adolescence, children involved in cross-reports between child welfare and animal control were often under the age of 5. Improved cross-reporting and stronger partnerships between human and animal welfare agencies may provide opportunity for earlier intervention and is likely to better many human and animal lives.

1. Introduction

A growing body of academic literature and research continues to point toward the importance of better understanding relationships between human and non-human animals (subsequently referred to as animals). In fact, the well-being of these populations is intertwined in many ways. Since children and animals often represent the most vulnerable beings in society, better protecting them remains paramount to better ensuring a higher quality of health and life for all in the community.

Key agencies in improving cross-reporting and better ensuring the safety of humans and animals in many communities are animal care and control. These agencies are often the designated responders to allegations of animal cruelty across the United States (U.S.). Few academic studies and research papers currently exist that utilize data from these critical agencies to gain a greater understanding of the incidents they respond to. Though often overlooked and underappreciated, the work of animal control agencies is often critical. Safe communities start with safe homes, and that includes the safety of animals who reside in them, as well as humans.

The primary focus of this study regards child involvement in reports of animal cruelty toward companion animals. Some cases involved cruelty toward wild animals; therefore, they are included but warrant further study as this is not an adequately researched topic.

2. Background

2.1. Child–Companion Animal Bond

Often representing the two most vulnerable beings in the home and community, better understanding the relationship between children and animals is critical in efforts to better protect both. Although this work will focus largely on children and companion animals, further research is needed to explore the relationship between children and wild animals.

An estimated 70% of U.S. households have at least one companion animal (APPA 2021). Dogs are the most common pets in the U.S., and 99% of dog “owners” indicate feeling these animals are either “part of the family” or “companions” (AVMA 2018). Companion animals are even more common in households that include one or more children aged 7 or older (75%; Christian et al. 2020).

Companion animals often play an important role in lives of children they cohabit with (Jalongo 2021). Whether providing comfort in times of sadness or increasing joy in times of happiness, research continues to indicate that the well-being of both children and animals in the home is often intertwined (Hawkins and Williams 2017). By exploring the quality of a child’s relationships with companion animals, we may catch a preview of the quality and nature of relationships that child is likely to have in the future with other humans and animals (Kerns et al. 2017).

Companion animals are also often part of households in which domestic violence occurs (80%; Faver and Strand 2003). In fact, when any form of family violence against humans (child abuse, partner abuse, or elder abuse) occurs in the home, any animal members of the household also share in the risk of experiencing abuse and harm (Monsalve et al. 2017). This risk often extends to animals not traditionally thought of as “pets”, including horses, cows, chickens, or any animal that humans form a bond with and find healing and support from (Cody et al. 2011).

Animals may be particularly important to the mental and emotional health of children experiencing one or more forms of family violence (partner abuse, child abuse, companion animal abuse, or elder abuse; Campbell 2020b). Children residing in abusive homes often do not experience the safe and secure home environment so critical for healthy growth and development. This lack of a stable and secure environment can result in many negative behavioral and emotional health outcomes (Lloyd 2018; Pingley 2017). Companion animals can help to bridge this gap and aide in healthier social-emotional development (Christian et al. 2020; Purewal et al. 2017).

2.2. Child Attachment to Animals

The concept of attachment has long been studied and reported in academic literature (see, e.g., Bowlby 1982). Though most often described in the context of the relationship of a child with their caregiver, attachment explores various aspects of relationships to measure the strength of the bond between the two. Varying levels of attachment include secure, insecure-ambivalent, insecure-avoidant, and insecure-disorganized (Ainsworth 1985). An additional level of attachment labeled disinhibited attachment appears to be more common among children who are “socially deprived” throughout youth, as many children residing in homes where family violence occurs often are. However, further study is required to determine its relationship to other forms of child maltreatment (Kay et al. 2016). This form of attachment is characterized by an absence of differentiation in response to adults, i.e., responds to adult strangers and family members in the same manner, and a lesser likelihood to seek out parents in adverse situations (Rutter et al. 2007).

With secure attachment considered optimal, having at least one such relationship in childhood has been associated with less anxiety, improved working memory and inhibition, more positive interactions with future intimate partners, and less conflict in interpersonal relationships. Conversely, when children do not have at least one secure attachment they are more likely to exhibit increased aggression, increased inclination to independence (to the detriment of relationships), and increased anxiety (Wanser et al. 2019). Experiencing toxic stress, common in homes where family violence occurs, creates strain on child-caregiver relationships, and is linked to insecure attachments between the pair—often increasing the risk for abuse or neglect (Khan et al. 2020).

As previously stated, although studies on attachment have long focused on relationships between children and caregivers, recent research has identified similar characteristics in child–companion animal relationships (Wanser et al. 2019). When a child’s caregiver is chronically abused, they may have had so much taken from them emotionally by the abuser that they have little emotional support left to give their children (Campbell and Thompson 2015). Companion animals in the home may provide a child a chance of experiencing many critical components of mental and emotional health (Hawkins and Williams 2017).

Companion animals may often become the center point of safety, or a secure base for exploration for children who know no other source of safety (Rockett and Carr 2017; Wanser et al. 2019). Studies have confirmed this idea by showing that a child’s level of attachment with humans does not predict their level of attachment with companion animals (Beetz et al. 2012). In fact, in a study of child maltreatment victims, abused children were four times more likely to be securely attached to an animal in the home (often a cat or dog) than their human caregiver (Wanser et al. 2019; Beetz et al. 2012). This stronger connection between children and animal companions in the absence of a strong/consistent human connection may be particularly true for younger children aged 3 to 6 (Bodsworth and Coleman 2001).

Another key concept regarding attachment is that the early relationships children form are critical in determining their inner working model. This model of what to expect from others is the lens from which they will view their world and future relationships (Zimmermann and Iwanski 2019). Animal companions can provide an additional perspective for children who would otherwise view the world through the distorted lens created by a caregiver’s abuse or neglect and reduce the likelihood of a lifetime of harmful and damaging relationships.

2.3. Child Perpetrators of Animal Cruelty

Though often a great source of comfort to both child and companion animal when their relationship is healthy and protected, this relationship can be harmful and damaging when not protected. When children commit acts of animal cruelty, we must pay attention. These harmful acts may be indicators of the child also being abused; research continues to show links between acts of animal cruelty and all forms of family violence (Jegatheesan et al. 2020). Additionally, acts of animal cruelty are often considered among the earliest indicators of conduct disorder and antisocial behaviors that often only worsen over time (Frick et al. 1993). Failure to detect and effectively intervene makes it more likely that many more animals and humans could suffer harm in the future. This harm extends to the child perpetrator, as continued steps down this road may create great difficulty in ever forming healthy and happy relationships.

Although some studies have reported a lower incidence of animal cruelty perpetration among children as they reach age 12 (McEwen et al. 2014), others have indicated a possible increase during adolescence among subsets of more violent humans (Ressler et al. 1988; Johnson and Becker 1997). Studies have strongly tied increases in animal cruelty perpetration in adolescence to the perceived acceptability of animal cruelty (Connor et al. 2021). Repeated acts of animal cruelty in youth warrants great concern and have been identified as a predictor for repeated acts of interpersonal violence when the child enters adulthood (Trentham et al. 2018).

Most studies that explore rates of animal cruelty perpetration among children rely on caregivers to report if their child is abusing animals. Studies describing domestic violence incidents in households with children indicate that children are often aware of much more than their caregivers realize, and it follows that they may also be engaging in many activities the caregiver has no knowledge of (Campbell and Thompson 2015). Children, particularly when acting as the solo perpetrator of harm to animals, may become better at concealing abusive acts as they grow older (McEwen et al. 2014). In fact, studies that explore animal cruelty histories in childhood among perpetrators of mass murder find they often committed these acts toward animals from other homes or neighborhoods, rather than against their own animal companion (Levin and Arluke 2009).

2.4. Serial Killers, School Shooters, and Mass Murderers

Although not all children who abuse animals go on to commit acts of mass murder or violence in the future, many who do commit these acts have history of committing acts of animal cruelty in youth. Notorious U.S. serial killers such as Jeffrey Dahmer and the “BTK Killer” describe beginning acts of cruelty on animals before moving on to committing similar acts on humans (DeMello 2021). Although some estimate the proportion of mass murderers, school shooters, and serial killers who have a history of animal cruelty to be much higher, conservative estimates still indicate at least 40% of mass murders have history of animal cruelty in youth (Arluke and Madfis 2014).

Studies have indicated warning signs in the manner acts of animal cruelty are perpetrated among serial killers, mass murderers, and other extremely violent criminals (Arluke et al. 2018). In many cases, the specific manner of harming animals perpetrated in youth mirrored the manner the killer used to later murder humans (Levin and Arluke 2009). These acts of animal cruelty perpetrated by serial killers and mass murderers are more commonly committed through personal contact such as with one’s own hands and are often against dogs or cats (Arluke et al. 2018; Levin and Arluke 2009). Torture may also be a common component of these abusive acts, particularly among serial killers (Levin and Arluke 2009).

Researchers have proposed multiple theories to explain why humans may target both animals and other humans in acts of violence or abuse. Two of the most frequently cited theories in exploring relationships between animal cruelty and other forms of violence or crime are the graduation hypothesis and general deviance theory (Gullone 2014). Though the theories differ in several ways, both indicate the importance of taking crimes against animals seriously (Arluke et al. 1999).

The graduation hypothesis proposes that humans may progress from the abuse of animals in childhood to committing violent acts against humans and is largely based on findings from retrospective studies that find adult perpetrators of violence to be more likely to have a history of animal cruelty in childhood (Hensley et al. 2009). One explanation for this “progression” in violence focuses on children who have been victimized by harm. Child victims of abuse by adults or bullying by peers may feel powerless to stop the perpetrator of their harm and begin to harm animals—as they often represent the most vulnerable beings in the child’s world (Wright and Hensley 2003). These child perpetrators of animal abuse may become desensitized to or begin to enjoy these acts, leading them to “graduate” to committing acts of abuse and violence toward other humans (Chan and Wong 2019).

Rather than viewing acts of violence toward humans as a progression from acts of abuse toward animals, the general deviance theory allows for acts of harm to humans to follow, precede, or be perpetrated concurrently with acts of harm to animals. This theory focuses on anti-social behavior collectively and its ties to disruptions of developmental processes within the perpetrator (Frick and Viding 2009), rather than viewing one form of violence/crime as building off the other. Animal cruelty is thus viewed as one of many crimes committed by the perpetrator who has a “general disposition” toward delinquency and aggression (Stupperich and Strack 2016). Researchers have found evidence to support this theory in identifying concurrent perpetration of animal cruelty and other forms of anti-social behavior, including violence against humans and other forms of crime (Dadds et al. 2002; Arluke et al. 1999).

2.5. Animal Cruelty in the Context of Family Violence

Perpetration of animal cruelty may often be an indicator of other forms of family violence occurring in the home (Riggs et al. 2021; Bright et al. 2018; DeGue and DiLillo 2009). A growing wealth of academic literature continues to link child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, and animal abuse (National Link Coalition 2021). Children exposed to intimate partner violence are three times more likely to commit acts of animal cruelty (Currie 2006). Risk for child perpetration of animal cruelty seems to rise when children are exposed to multiple forms of family violence. One study found that although 29% of children who were exposed to domestic violence committed acts of animal cruelty, the rate increased to 54% among children exposed to domestic violence AND physical child abuse (McEwen et al. 2014). Increased prevalence of animal cruelty perpetration has also been noted among children who have an ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) score of 4 or greater (Bright et al. 2018). Though likely harmful for children, exposure to animal cruelty has historically not been included in ACE scores (Felitti et al. 1998).

Although experiencing family violence in youth does appear to make one more likely to commit acts of animal cruelty, many children experience family violence and do not go on to commit acts of animal cruelty (Hawkins et al. 2019). Further study is needed to gain a greater understanding of the relationship between family violence and child perpetration of animal cruelty.

When adults are the perpetrators of abuse to animals, we should consider that the act may also be intended to inflict emotional harm to humans in the home who are strongly attached to the animal. Domestic violence perpetrators who also abuse companion animals are among the highest risk offenders to all who reside in the home (Campbell et al. 2021). The high risk of harm from these animal-abusing, domestic violence perpetrators often extends both to the community they reside in, as well as to law enforcement officers responding to any reported incidents in the home (Campbell 2021).

Animal cruelty has also been shown as a clear method utilized by perpetrators of domestic violence to suppress or discourage reporting of abuse in the home (Faver and Strand 2003). These cruel acts of harm to animals are often extremely effective in dissuading victims of abuse from reporting (Roguski 2012). Perpetrators may kill animals to show the victim what will happen to them if they report their abuse or threaten to kill animals if a report is ever made (Roguski 2012). Threats of animal cruelty rarely seem to be idle ones (Ascione 2007). If perpetrators threaten animal cruelty, they usually follow through—and humans in the home know this. Many will remain silent and endure abuse for years to come rather than jeopardize the well-being of their cherished animal companions (Barrett et al. 2018).

2.6. Animal Cruelty against Wild Animals

There remains a great gap in the literature regarding child perpetration of animal cruelty against wild animals. This gap may exist in part due to the difficulties in detecting this abuse. Abuse of wild animals may be more likely to occur in isolated areas where few humans have opportunity to detect and report the abuse. Additionally, harm may be more quickly attributed to acts of other wild animals among this subset. Further, a combination of lesser legal protections for wild animals and the social sanctioning of hunting wild animals, particularly in more rural areas, could result in the offense being taken less seriously by a potential report source (Gacek 2019).

In a study of survey responses of prison inmates, the abuse of wild animals was reported more commonly among inmates who resided in urban areas compared with those living in more rural communities (Tallichet and Hensley 2005). Although one may assume greater access to wild animals in rural areas, studies also indicate cats are much more frequent in rural homes than urban ones and more likely to be abused in rural environments by both adolescent and adult perpetrators of animal cruelty (Connor et al. 2021; Tallichet and Hensley 2005).

Key in determining one’s risk for abusing wild animals is the perceived acceptableness of the act (Signal et al. 2017). As is true with companion animals, identifying what motivates the perpetrator to harm the wild animal (anger, imitation, fun, or dislike) could indicate risk for future acts of cruelty toward animals and humans (Hensley and Tallichet 2008).

3. Materials and Methods

Animal Control Data/Reports Analyzed for This Paper

The data analyzed in this study were acquired through a public records request. As publicly available information it did not meet criteria for Institutional Board Review (IRB). The dataset includes all animal control runs for reports of animal neglect or abuse from 2016 to 2018. The animal control agency in this study is municipal and provides services for companion animals and wild animals in rural and urban areas. Although the name of the city the data were collected in has been excluded from this paper to protect anonymity, it is a large, urban city (population greater than 250,000) in a Midwestern U.S. State. Additional demographic information of the study city include:

- 52% of the population is female

- 25% of the population is under the age of 18 years

- 73% of the population identifies their race as “white”

- Median household income < USD 50,000

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 27. Results reported as percentages indicate the proportion of affirmative responses when a response was indicated. Included report narratives were altered if necessary to protect anonymity, including omitting identifiable locations in the community and more detailed physical descriptions of those involved in the case. In some cases, where a child reported acts of animal cruelty by another child, children were recorded in the study as both the perpetrator and reporter of the incident.

4. Results

Once duplicate calls were removed from the dataset, 5226 unique abuse/neglect incidents remained. For 3791 (73%) of these incidents, an official report was made, indicating a higher level of concern regarding the nature of the act and/or for the well-being of the animal victimized. A total of 53 (1.4%) of these official reports mentioned children as part of the incident in some manner and were the focus of this study. A total of 72% of reports that mention children in some manner involved allegations of animal abuse, whereas the remaining 28% indicated concern for animal neglect.

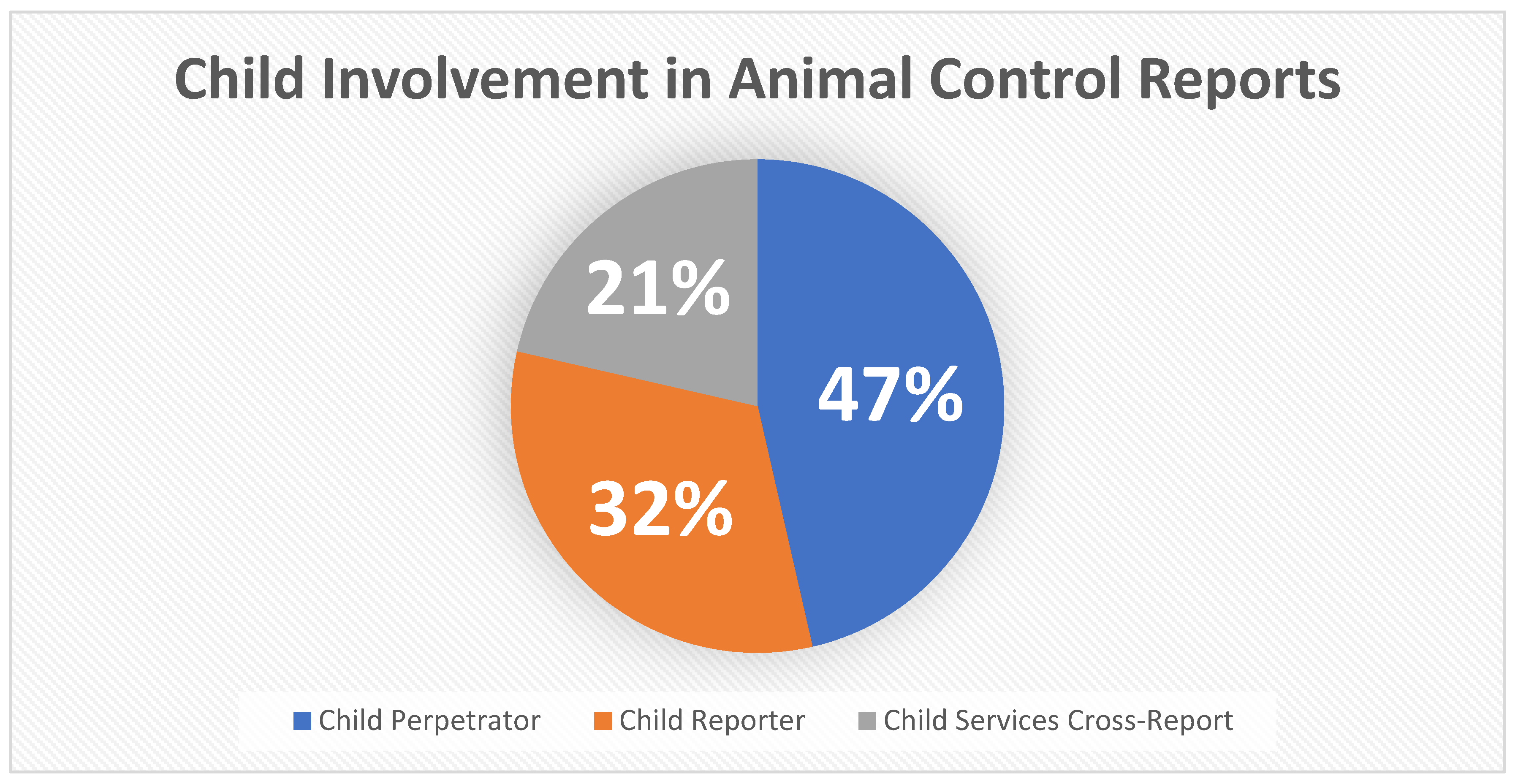

The different manners in which children were included in animal control reports were as perpetrator of the act (solely, or as co-perpetrator with other children and/or adults), a reporter of the act, or due to a child victim services agency reporting animal cruelty while responding to concerns for children in the home (Figure 1). The average age of child perpetrators of animal cruelty was 10.7 years, whereas the average age of children reporting animal cruelty was 9.5 years (Table 1). Although the age of children involved in a cross-report was rarely noted, it was often implied that the child was likely very young; for example, a report mentioned diapers or indicated the child was unable to describe where they lived.

Figure 1.

Child involvement in animal control reports.

Table 1.

Child age by involvement in report.

Of the 53 animal control reports that mentioned children, 70% involved a dog, 18% involved a cat, and 13% involved wild animals (rabbits, geese, and raccoons). When the breed of dog was indicated, 50% of the time it was a “pit bull”. It is important to note however that the term “pit bull” is often applied to a range of different breeds and may better indicate general physical appearance rather than actual breed of dog (Gunter et al. 2016).

Differences were noted when incidents were stratified by classification of the animals involved (companion animals vs. wild animals; Table 2). Children were more often found to act as a solo perpetrator of animal cruelty when the incident involved companion animals (36%) than when the incident involved wild animals (25%). Although 14% of child-perpetrated acts of animal cruelty involved an adult as co-perpetrator, there were no reports of children abusing wild animals with adults. Children reporting animal cruelty toward companion animals always knew the perpetrator’s name and/or address, but in two of the three cases of animal cruelty against wild animals reported by children, the perpetrator was unknown to the child.

Table 2.

Child involvement in animal control report by classification of animal.

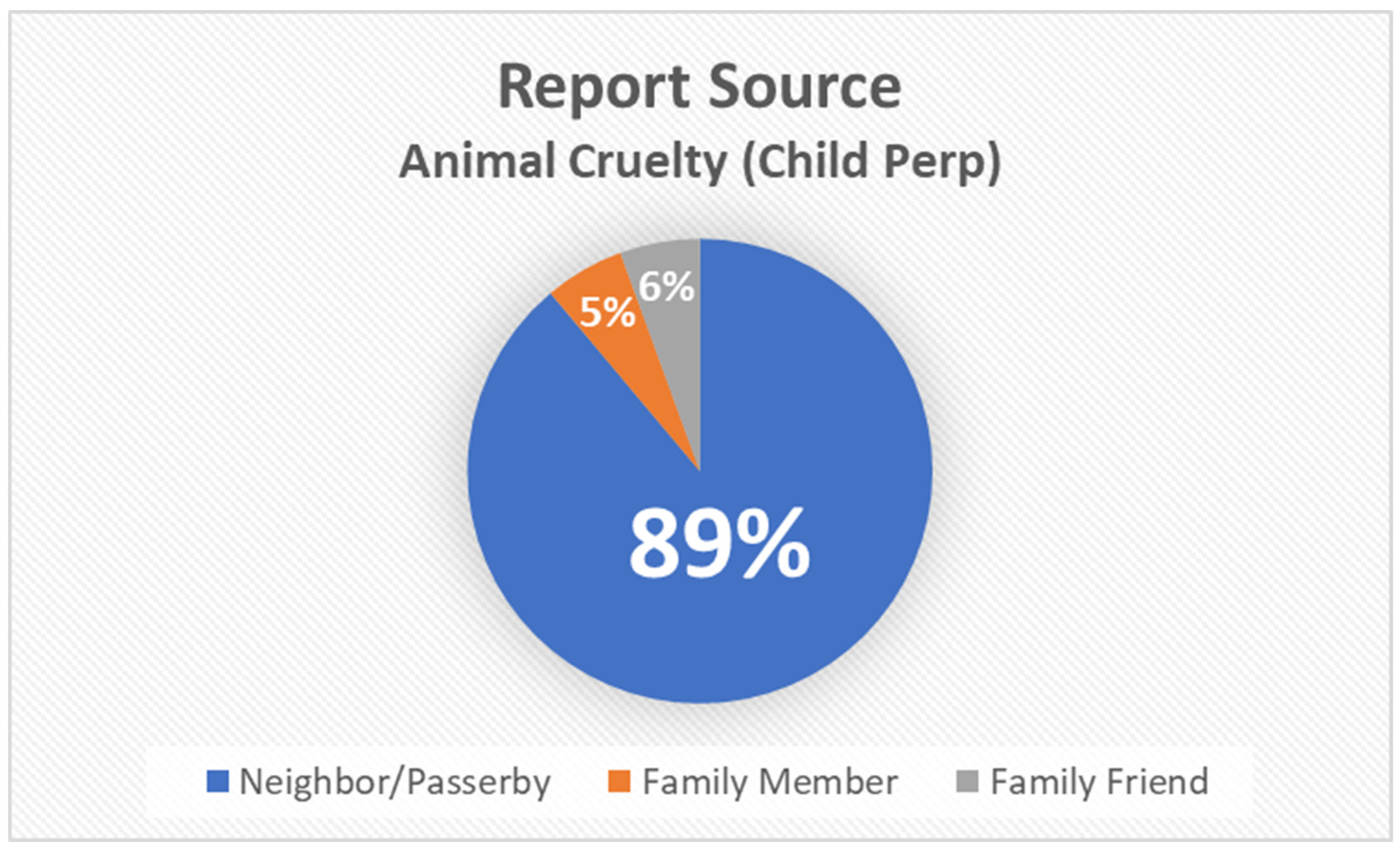

4.1. Children as Perpetrators of Animal Cruelty

When a report source was indicated for cases of child-perpetrated animal cruelty, 89% of the time it was a neighbor or passerby who made the report (Figure 2). All cases of animal cruelty perpetrated by children involved abuse rather than neglect. Acts of abuse were most often inflicted to dogs (62%) or cats (23%). A total of 15% of reported child-perpetrated acts of animal abuse involved wild animals.

Figure 2.

Report source (when indicated) of animal cruelty perpetrated by children.

Children were described as either the solo perpetrator of abuse (35%) or engaging in acts of abuse along with peers (54%) and/or adults (12%) (Table 3). Incident narratives indicate variance in manner and method of animal cruelty (Table 4). Children either inflicted the abusive act with a weapon such as a knife or gun (5% companion animals; 25% wild animals), with another object such as a stick or a rock (36% companion animals; 50% wild animals), or with their hands or feet (45% companion animals; 25% wild animals) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Method of Inflicting Animal Abuse Among Child Perpetrators.

Table 4.

Animal Control Report Narratives (Child Perpetrator).

4.2. Children as Reporters of Animal Cruelty

Children report acts of animal cruelty, either by contacting animal control directly, or by disclosing to a trusted adult (school counselor, teacher, parent, etc.) who then reports to animal control. Most reports of animal cruelty made by children involve either neglect or severe acts of animal abuse perpetrated by adults often known to the child (father, mom’s boyfriend, friend’s father, etc.). In one instance, a group of children removed a dog from the home themselves before reporting.

These severe acts of abuse witnessed by children were most often inflicted with the bare hands of the perpetrator and often involved torturing, slamming into a wall, drowning, or strangulation (Table 5). Although dogs were the most common victim of abuse or neglect reported by children, all three cases reported by children that involved “wild animals” detailed severe torturing and/or the death of the animal. Although all adults were known to the children making a report of animal cruelty toward companion animals, two of the three child reports of animal cruelty toward wild animals indicated that the adult perpetrator was a stranger to the child.

Table 5.

Animal Control Report Narratives (Child Reporter).

4.3. Child Services-Animal Control Cross Report

Although no formal child services/animal welfare cross-discipline reporting agreement is known to exist in the study community, there were still several reports of animal abuse or neglect made as a “cross-report” by a child protective service agency or other victim-serving agency (law enforcement, social services, etc.) while visiting a home to check on the welfare of children who reside there (Table 6). In nearly every case, the concerns for both children and the animal were the same (both lost, both injured, both living in poor conditions, etc.). All cross-reporters indicated concern for a dog residing in the home (one report mentioned a cat in home as well). No cross-reports involved wild animals.

Table 6.

Animal Control Report Narratives (Child Services Cross-Report).

5. Discussion

This study is among the first to utilize animal control data and narratives to explore the involvement of children in reports of animal cruelty and quantify many of the characteristics reported. This important and rarely utilized data-source can provide additional insight in this critical area and better inform efforts to protect humans and animals. Although most prior studies exploring acts of animal cruelty utilize victim self-reports or caregiver reports regarding any acts of cruelty perpetrated by their children, by focusing on animal control reports, we gain new perspective and reduce opportunity for self-reporting biases since nearly all animal control reports are made by someone who is not a member of the offender’s household.

Consistent with estimates from previous papers that 80% of animal control reports are made by neighbors or those passing by (Campbell 2020a), this study found that 89% of reports of animal cruelty involving a child perpetrator (when report source is known) were made by a neighbor or passerby. This unique report source neighbors only make 8% of total intimate partner violence reports received by law enforcement (Campbell 2020a) could provide additional critical information regarding potential harm to humans in the home as well. Agencies responding to reports of animal cruelty made by a neighbor, must also ask about any concerns relating to humans in the home. It may be one’s best chance to better engage neighbors regarding concerns for abuse of animals and humans in the home.

Children were rarely mentioned in animal control narratives (only 1% of official reports). This finding is unlikely to be an accurate reflection of the proportion of animal control incidents that impact children. Since companion animals are even more likely to reside in homes that have at least one child aged 7 or older (Christian et al. 2020), one must assume that children often reside in households where animal cruelty incidents occur. These children are likely to be significantly impacted by these abusive acts.

Although the age of the children involved in animal cruelty incidents in this study was not often mentioned, when indicated, child reporters and perpetrators were often in early adolescence. This means animal control may often interact with children directly before they reach mid-adolescence where other studies have indicated concerns for increased incidence of perpetration and greater difficulty in detection (Johnson and Becker 1997; McEwen et al. 2014). If involved in the report as perpetrator and in the absence of effective intervention, children may work harder to conceal future acts of animal cruelty. Studies have found inmates with convictions for multiple acts of interpersonal violence more likely to have concealed acts of animal cruelty in youth (Tallichet and Hensley 2009).

Animal control agencies should consider always noting if children reside in the home (even if not a reporter or perpetrator), given they may often share risk of harm with animals in these homes. Mandatory cross-reporting to ensure the appropriate agency ascertains the well-being of children in homes deemed unsafe for companion animals must be strongly considered. This action is likely to result in additional opportunity to detect abuse earlier—especially if the perpetrator is using animal abuse to discourage reports for other forms of abuse occurring in the home—and more effectively intervene.

When children engage in acts of animal cruelty that are reported to animal control, these acts most often involve a dog or cat. Overall, children were more likely to commit the abusive act with their own hands or feet. Studies have identified that these more personal, hands-on abusive acts warrant concern and can be an indicator of future acts of extreme violence (Arluke and Madfis 2014). In fact, 90% of child perpetrators of school shootings who also had a history of animal cruelty abused animals in an up-close personal manner (Arluke and Madfis 2014), as did 80% of a sample of incarcerated men (“hit animal”; Henderson et al. 2011).

In addition to acts of cruelty to companion animals, children also commit acts of cruelty to wild animals. Though significantly fewer cases involving wild animals compared with companion animals were reported in this dataset, children are likely extremely impacted by these incidents as well. Nearly all reports of cruelty to wild animals involved torture and/or fatal injury. More study is warranted to better understand differences between how children respond to abuse of companion animals compared with the abuse of wild animals such as geese, racoons, and rabbits.

Greater attention has been shown in recent years to links between animal cruelty and other forms of family violence; however, most studies tend to focus on companion animals. Future studies must consider possible links between acts of cruelty to wildlife and family violence. Though cruelty of companion animals is reported more frequently than cruelty to wild animals, this may not accurately reflect prevalence differences. Although the opportunity to abuse companion animals is ever-present due to proximity, this same proximity often provides opportunities for others to detect and report.

Given that the abuse of companion animals is likely to be underreported, there may be even greater barriers to detection and reporting of acts of cruelty against wild animals. This reduced likelihood of detection may draw perpetrators of animal cruelty to focus on wild animals as victims. In fact, notorious serial killers have been reported to include wild animals in their acts of abuse and torture (Levin and Arluke 2009). Regardless of whether they victimized wild animals or companion animals, many serial killers enact a similar modis operandi of violence on humans as an adult as they did to animals in their youth (Levin and Arluke 2009).

Children commit abusive acts toward animals with their peers, with an adult, with peers and an adult, or alone. In this study, children were more likely to engage in acts of animal abuse with peers than with adults or acting alone. Children may be engaging in this behavior with peers for a variety of reasons, including to “fit in” and reduce risk of being the target of the group. It is important that communities explore programs for school-aged children regarding the harm not only to the animal but to the child themselves when they engage in these acts of cruelty. When peer pressure slants toward harm and abuse as opposed to away from it, communities are likely in great danger of continuing harm and abuse against animals and humans.

Children were also reported to engage in acts of animal cruelty along with adults. These adults were often known to the child personally. The participation of a trusted adult adds an additional layer of concern for reinforcement in the mind of the child regarding the acceptability of these abusive acts and should raise one’s level of concern regarding the wellbeing of all humans and animals who reside in that environment. Witnessing an adult abuse an animal has been shown to make a child 3 to 8 times more likely to abuse animals themselves (Johnson 2018). When children not only witness an adult abuse an animal, but perpetrate the act with them, this likely only further increases risk for them to perpetrate acts of animal cruelty in the future.

In several cases, adults were not noted as participating in the abuse but were indicated as being present when the child perpetrated the abuse and “not seeming to care”. Even though they did not participate in the current incident, if the adult is not concerned by the act of cruelty, they too may engage in similar acts and likely in front of their children. Studies continue to find that this type of early exposure to acts of animal cruelty makes children more likely to go on to commit these acts as they get older (Henry 2004).

Children only used weapons (knife or gun) in acts of animal cruelty when perpetrating alone. The literature is clear regarding how the use of a weapon dramatically increases risk for fatal outcomes in other acts of abuse, such as intimate partner violence (Gold 2020). The same is likely true in this scenario. Although there may be greater opportunity to detect fatal harm to companion animals, one must assume that many fatal acts by solo child perpetrators of abuse toward wild animals go undetected. Even if the animal’s body is discovered, it may be more likely to be attributed to other wild animals than a human perpetrator.

When children reported animal cruelty, it most often involved acts that were among the most severe included in this study. In fact, nearly all fatal incidents, severely abusive acts, and the worst cases of animal neglect were reported by children. These children are likely to be significantly emotionally impacted by witnessing this harm, and likely in need of mental health services.

Most of the severe acts of animal cruelty reported by children were perpetrated by a parent or intimate partner of the child’s parent. Concerningly, studies often report high risk of animal cruelty in homes where intimate partner violence occurs, and injuries inflicted on animals by the perpetrator may even mirror injuries they inflict on their intimate partner (Johnson 2018). Research continues to indicate the alarming increasing risk for severe harm for all who reside in homes where animal abuse occurs in the context of family violence (Campbell et al. 2021).

Since in all cases of companion animal cruelty reported by children, the perpetrator was known to the child, the animal was also likely known by the child. Children are extremely emotionally impacted by witnessing acts of cruelty to animals, and possibly even more so when they have a personal relationship with the animal and perpetrator. The child is likely to begin (or continue to) fear for their own safety and wellbeing at the hands of the individual who committed the act—even more so considering the child reported the incident.

If perpetrators learn who made the report, this child would be in immediate danger of suffering the same or even worse fate as the animal harmed by the offender. Danger is obviously increased if children feel the need to take further action for the wellbeing of the animal. In one instance in this study, children removed the dog themselves from the home before reporting. These dangerous acts by children to protect animals have also been documented in intimate partner violence literature. In fact, one study found that 78% of children in homes where intimate partner violence occurred took direct action to protect a pet from abuse (McDonald et al. 2015). Given the concerns that children may take direct action themselves to protect animals and are likely at great risk from the perpetrator if their report or action is detected, cross-reporting between animal control and child services may be just as critical when children report animal abuse as when they perpetrate it. In both instances the long-term well-being of all humans and animals who reside in the home must be considered and action taken to best ensure a positive outcome for all.

Cross-Reporting between Human and Animal Welfare Agencies

There were several reports included in this study, that originated from other agencies involved in ascertaining the welfare of children attached to these animals. These agencies included child protective services, law enforcement, and social service providers. The astute observations and reports to animal control made by these professionals should be applauded. In many communities this critical cross-reporting rarely occurs. It is important to note that in most cases where a cross-report occurred, the child and pet shared the same concerning conditions. Whether it be lost and wandering alone in a neighborhood, suffering sickness or poor health, physical injury, or living in unsafe conditions, the well-being of these child–pet pairs was often intertwined.

Furthermore, children involved in a cross-report between child services and animal control were often much younger than children involved as a perpetrator or reporter of animal cruelty. Narratives of cross-reports often implied the child was likely under the age of 5 years. These children are in the age range where pet–child attachment may be especially critical for the mental health of both, particularly in homes where domestic violence occurs (Bodsworth and Coleman 2001).

Children under the age of 5 years have been found to be disproportionately represented in households where partner abuse occurs (Campbell et al. 2020) and are at 60 times the risk of suffering child maltreatment when residing in these conditions (Thackeray et al. 2010). Animal control cross-reporting with child welfare agencies may provide a great opportunity to better identify young child–animal companion pairs at great risk of harm, and effectively work to prevent the future harm of both child and animal.

This study adds to the growing mountain of literature on the importance of child-animal relationships and the dire need for stronger partnerships between human welfare and animal welfare organizations (Arkow 2020; Randour et al. 2021). The data seem to indicate a need for a cross-report with child services (ideally any time children reside in a home where animal cruelty occurs), at the very least whenever a child is a perpetrator or reporter of the act of animal cruelty. In both cases, these children will be significantly impacted by the incident and in need of mental health services at least. If animal control officers ever deem a home unsafe for animals, and children reside in the home too, a cross-report with child services is a must.

It was not indicated in reports how often animal control cross-reported to child welfare. Every case of cross-reporting in this study originated from a child welfare organization. All citizens in the U.S. State where the study took place are mandated reporters of child maltreatment. Animal welfare agencies must consider cross-reporting with child welfare agencies whenever children are involved in animal cruelty cases in any way (perpetrator, reporter, or witness). Although no cross-reports involved wild animals in this study, professionals must also consider cross-reporting when wild animals are abused by children or by adults who care for children. These acts also warrant concern for the well-being of all in the household, as well as for any animals who may encounter the perpetrator in the future.

Improving relations between human and animal welfare agencies and encouraging systematic cross-reporting are important steps we can take to improve our overall response to family violence. Stronger cross-discipline partnerships such as this are likely to create opportunities to bridge existing gaps in family violence victim services. By working together, these critical agencies are likely to better reach and assist more humans and animals in great need of assistance.

6. Conclusions

As the first paper in the literature to utilize U.S. animal control data and report narratives to explore child involvement in animal cruelty reports, this study is intended to encourage further research in this area. Animal control data can provide a unique perspective of these issues and allow for more informed efforts to not only better protect animals, but humans as well. Regardless of how children experience acts of animal cruelty, albeit as perpetrator, reporter, witness, or as a victim along with the animal, they are likely to be significantly impacted by the event. Children can form strong attachments to animals and witnessing their harm can be as traumatic or even more traumatic than witnessing harm to other humans.

Animal cruelty cases that involve children in any way warrant a referral for mental health services at the very least and a call to child services if any concerns arise regarding the welfare and safety of any humans in the home. Cross-reporting between animal welfare and child welfare agencies may provide the best opportunity for early intervention and reduce risk of future harm for children and pets. Although neighbors rarely report the abuse of humans (8% of intimate partner violence reports are made by neighbors), they report 89% of animal cruelty cases. Given their proximity to the home, neighbors reporting animal abuse may also have concerns regarding the well-being and safety of humans in the family unit. Ensuring responders to animal cruelty incidents reported by neighbors ask about humans too may be our best chance to better engage neighbors in efforts to prevent the abuse of humans and animals in the future.

In many communities, no formal animal control agency exists. This grave oversight in public safety only increases the risk of harm for humans and animals in the community. Even when designated responders for animal control are part of community safety measures, many incidents are likely to go unreported. How much more so when no such organization even exists? Every call reporting animal cruelty is an opportunity to not only protect and ensure the safety of animals, but humans too. When no such method for reporting exists, abuse likely remains in the shadows—where it thrives. One cannot best protect the people in one’s community until the animals who reside there are safe as well.

7. Study Limitations

As the first known study to describe many of the aforementioned characteristics of animal control reports involving children, this paper is intended to be a starting point for future research. Not all cases of animal cruelty are reported to the authorities. This study is limited to incidents of animal cruelty that were reported to animal control. Given the small sample size, further study is necessary to support study findings.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ainsworth, Mary D. 1985. Patterns of infant-mother attachments: Antecedents and effects on development. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 61: 771–91. [Google Scholar]

- APPA. 2021. Pet Industry Market Size, Trends, & Ownership Statistics. Available online: https://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Arkow, Phil. 2020. Human-Animal Relationships and Social Work: Opportunities Beyond the Veterinary Environment. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal: C & A 37: 573–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arluke, Arnold, Adam Lankford, and Eric Madfis. 2018. Harming animals and massacring humans: Characteristics of public mass and active shooters who abused animals. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 36: 739–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arluke, Arnold, and Eric Madfis. 2014. Animal Abuse as a Warning Sign of School Massacres: A Critique and Refinement. Homicide Studies 18: 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arluke, Arnold, Jack Levin, Carter Luke, and Frank Ascione. 1999. The relationship of animal abuse to violence and other forms of antisocial behavior. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 14: 963–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, Frank R. 2007. Emerging research on animal abuse as a risk factor for intimate partner violence. In Intimate Partner Violence. Edited by K. Kendall-Tackett and S. Giacomoni. Kingston: Civic Research Institute, pp. 3.1–3.17. [Google Scholar]

- AVMA. 2018. AVMA Pet Ownership and Demographics Sourcebook: 2017–2018 Edition. Schaumburg: American Veterinary Medical Association. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Betty Jo, Amy Fitzgerald, Amy Peirone, Rochelle Stevenson, and Chi Ho Cheung. 2018. Help-Seeking Among Abused Women With Pets: Evidence From a Canadian Sample. Violence and Victims 33: 604–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, Andrea, Henri Julius, Dennis Turner, and Kurt Kotrschal. 2012. Effects of social support by a dog on stress modulation in male children with insecure attachment. Frontiers in Psychology 3: 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bodsworth, Wendie, and Grahame Coleman. 2001. Child-companion animal attachment bonds in single and two-parent families. Anthrozoös 14: 216–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, John. 1982. Attachment and Loss, 2nd ed. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bright, Melissa A., Mona Sayedul Huq, Terry Spencer, Jennifer W. Applebaum, and Nancy Hardt. 2018. Animal cruelty as an indicator of family trauma: Using adverse childhood experiences to look beyond child abuse and domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect 76: 287–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Andrew M. 2020a. An increasing risk of family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International Reports 2: 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Andrew M. 2020b. Protecting Pets and Humans Too. Sheriff & Deputy, July/August 2020. pp. 54–55. Available online: https://www.campbellresearchandconsulting.com/uploads/1/2/0/8/120832937/protecting_pets_and_humans_too__campbell_nsa_.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Campbell, Andrew M. 2021. Behind the mask: Animal abuse perpetration as an indicator of risk for first responders to domestic violence. Forensic Science International: Animals and Environments 1: 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Andrew M., and Shannon L. Thompson. 2015. The emotional maltreatment of children in domestically violent homes: Identifying gaps in education and addressing common misconceptions. The risk of harm to children in domestically violent homes mandates a well-coordinated response. Child Abuse & Neglect 48: 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Andrew M., Ralph A. Hicks, Shannon L. Thompson, and Sarah E. Wiehe. 2020. Characteristics of Intimate Partner Violence Incidents and the Environments in Which They Occur: Victim Reports to Responding Law Enforcement Officers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 35: 2583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Andrew M., Shannon L. Thompson, Tara L. Harris, and Sarah E. Wiehe. 2021. Intimate Partner Violence and Pet Abuse: Responding Law Enforcement Officers’ Observations and Victim Reports from the Scene. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: 2353–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Heng Choon Oliver, and Rebecca W. Wong. 2019. Childhood and adolescent animal cruelty and subsequent interpersonal violence in adulthood: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior 48: 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, Hayley, Francis Mitrou, Rebecca Cunneen, and Stephen R. Zubrick. 2020. Pets are associated with fewer peer problems and emotional symptoms, and better prosocial behavior: Findings from the longitudinal study of Australian children. The Journal of Pediatrics 220: 200–6.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cody, Patricia, Lori Steiker, and Mary Szymandera. 2011. Equine Therapy: Substance Abusers’ “Healing Through Horses”. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 11: 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, Melanie, Candace Currie, and Alistair B. Lawrence. 2021. Factors Influencing the Prevalence of Animal Cruelty During Adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: 3017–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Currie, Cheryl L. 2006. Animal cruelty by children exposed to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect 30: 425–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadds, Mark R., Cynthia M. Turner, and John McAloon. 2002. Developmental links between cruelty to animals and human violence. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 35: 363–82. [Google Scholar]

- DeGue, Sarah, and David DiLillo. 2009. Is Animal Cruelty a “Red Flag” for Family Violence?: Investigating Co-Occurring Violence Toward Children, Partners, and Pets. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 24: 1036–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMello, Margo. 2021. Violence to Animals. In Animals and Society. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 280–307. [Google Scholar]

- Faver, Catherine A., and Elizabeth B. Strand. 2003. To leave or to stay? Battered women’s concern for vulnerable pets. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 18: 1367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, Vincent J., Robert F. Anda, Dale Nordenberg, David F. Williamson, Alison M. Spitz, Valerie Edwards, Mary Koss, and James S. Marks. 1998. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14: 245–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, Paul J., and Essi Viding. 2009. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology 21: 1111–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, Paul, Benjamin Lahey, Rolf Loeber, Lynne Tannenbaum, Yolanda Van Horn, Mary Christ, Elizabeth A. Hart, and Kelly Hanson. 1993. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: A meta-analytic review of factor analyses and cross-validation in a clinic sample. Clinical Psychology Review 13: 319–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, James. 2019. Confronting animal cruelty: Understanding evidence of harm towards animals. Manitoba Law Journal 42: 315. [Google Scholar]

- Gold, Liza H. 2020. Domestic Violence, Firearms, and Mass Shootings. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 48: 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullone, Eleonora. 2014. An evaluative review of theories related to animal cruelty. Journal of Animal Ethics 4: 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, Lisa M., Rebecca T. Barber, and Clive D. Wynne. 2016. What’s in a Name? Effect of Breed Perceptions & Labeling on Attractiveness, Adoptions & Length of Stay for Pit-Bull-Type Dogs. PLoS ONE 11: e0146857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hawkins, Roxanne D., and Joanne M. Williams. 2017. Childhood attachment to pets: Associations between pet attachment, attitudes to animals, compassion, and humane behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Roxanne D., Shelby E. McDonald, Kelly O’Connor, Angela Matijczak, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2019. Exposure to intimate partner violence and internalizing symptoms: The moderating effects of positive relationships with pets and animal cruelty exposure. Child Abuse & Neglect 98: 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Brandy B., Christopher Hensley, and Suzanne E. Tallichet. 2011. Childhood Animal Cruelty Methods and Their Link to Adult Interpersonal Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 26: 2211–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henry, Bill C. 2004. The Relationship between Animal Cruelty, Delinquency, and Attitudes toward the Treatment of Animals. Society & Animals 12: 185207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hensley, Christopher, and Suzanne E. Tallichet. 2008. The effect of inmates’ self-reported childhood and adolescent animal cruelty: Motivations on the number of convictions for adult violent interpersonal crimes. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 52: 175–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, Christopher, Suzanne E. Tallichet, and Erik L. Dutkiewicz. 2009. Recurrent childhood animal cruelty: Is there a relationship to adult recurrent interpersonal violence? Criminal Justice Review 34: 248–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalongo, Mary Renck. 2021. Pet Keeping in the Time of COVID-19: The Canine and Feline Companions of Young Children. Early Childhood Education Journal, 1–11, Prepublished online 18 August 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegatheesan, Brinda, Maire-Jose Enders-Slegers, Elizabeth Ormerod, and Paula Boyden. 2020. Understanding the Link between Animal Cruelty and Family Violence: The Bioecological Systems Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Scott A. 2018. Animal cruelty, pet abuse & violence: The missed dangerous connection. Forensic Research & Criminology International Journal 6: 403–15. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Bradley R., and Judith V. Becker. 1997. Natural born killers? The development of the sexually sadistic serial killer. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25: 335–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, Catherine, Jonathan Green, and Kishan Sharma. 2016. Disinhibited Attachment Disorder in UK Adopted Children During Middle Childhood: Prevalence, Validity and Possible Developmental Origin. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 44: 1375–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kerns, Kathryn A., Amanda J. Koehn, Manfred H. M. van Dulmen, Kaela L. Stuart-Parrigon, and Karin G. Coifman. 2017. Preadolescents’ relationships with pet dogs: Relationship continuity and associations with adjustment. Applied Developmental Science 21: 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khan, Faaiza, Jia Y. Chong, Jaclyn C. Theisen, R. Chris Fraley, Jami F. Young, and Benjamin L. Hankin. 2020. Development and change in attachment: A multiwave assessment of attachment and its correlates across childhood and adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 118: 1188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, Jack, and Arnold Arluke. 2009. Refining the link between animal abuse and subsequent violence. In The Link between Animal Abuse and Violence. Edited by A. Linzey. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, pp. 163–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, Michele. 2018. Domestic Violence and Education: Examining the Impact of Domestic Violence on Young Children, Children, and Young People and the Potential Role of Schools. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDonald, Shelby E., Elizabeth A. Collins, Nicole Nicotera, Tino O. Hageman, Frank R. Ascione, James Herbert Williams, and Sandra A. Graham-Bermann. 2015. Children’s experiences of companion animal maltreatment in households characterized by intimate partner violence. Child Abuse & Neglect 50: 116–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McEwen, Fiona S., Terrie E. Moffitt, and Louise Arseneault. 2014. Is childhood cruelty to animals a marker for physical maltreatment in a prospective cohort study of children? Child Abuse & Neglect 38: 533–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monsalve, Stefany, Fernando Ferreira, and Rita Garcia. 2017. The connection between animal abuse and interpersonal violence: A review from the veterinary perspective. Research in Veterinary Science 114: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Link Coalition. 2021. Resource Materials. Available online: https://nationallinkcoalition.org/resources/articles-research (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Pingley, Terra. 2017. The Impact of Witnessing Domestic Violence on Children: A Systematic Review. Social Work Master’s Clinical Research Papers. 773. Available online: https://ir.stthomas.edu/ssw_mstrp/773 (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Purewal, Rebecca, Robert Christley, Katarzyna Kordas, Carol Joinson, Kerstin Meints, Nancy Gee, and Carri Westgarth. 2017. Companion animals and child/adolescent development: A systematic review of the evidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14: 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randour, Mary Lou, Martha Smith-Blackmore, Nancy Blaney, Daniel DeSousa, and Audrey-Anne Guyony. 2021. Animal abuse as a type of trauma: Lessons for human and animal service professionals. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 22: 277–88. [Google Scholar]

- Ressler, Robert K., Ann W. Burgess, and John E. Douglas. 1988. Sexual Homicide: Patterns and Motives. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riggs, Damien W., Nik Taylor, Heather Fraser, Catherine Donovan, and Tania Signal. 2021. The link between domestic violence and abuse and animal cruelty in the intimate relationships of people of diverse genders and/or sexualities: A binational study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: NP3169–NP3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rockett, Ben, and Sam Carr. 2017. Animals and attachment theory. Society & Animals 22: 415–33. [Google Scholar]

- Roguski, Michael. 2012. Pets as Pawns: The Co-Existence of Animal Cruelty and Family Violence. Auckland: Royal New Zealand Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Available online: http://nationallinkcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/DV-PetsAsPawnsNZ.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Rutter, Michael, Celia Beckett, Jenny Castle, Emma Colvert, Jana Kreppner, Mitul Mehta, Suzanne Stevens, and Edmund Sonuga-Barke. 2007. Effects of profound early institutional deprivation: An overview of findings from a UK longitudinal study of Romanian adoptees. European Journal of Developmental Psychology 4: 332–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signal, Tania, Nik Taylor, and A. Maclean. 2017. Pampered or pariah: Does animal type influence the interaction between animal attitude and empathy? Psychology, Crime & Law 24: 527–37. [Google Scholar]

- Stupperich, Alexandra, and Micha Strack. 2016. Among a German sample of forensic patients, previous animal abuse mediates between psychopathy and sadistic actions. Journal of Forensic Sciences 61: 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallichet, Suzanne E., and Christopher Hensley. 2005. Rural and Urban Differences in the Commission of Animal Cruelty. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 49: 711–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallichet, Suzanne E., and Christopher Hensley. 2009. The social and emotional context of childhood and adolescent animal cruelty: Is there a link to adult interpersonal crimes? International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 53: 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, Jonathan D., Roberta Hibbard, and M. Denise Dowd. 2010. Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect, & Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Intimate partner violence: The role of the pediatrician. Pediatrics 125: 1094–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trentham, Caleb E., Christopher Hensley, and Christina Policastro. 2018. Recurrent Childhood Animal Cruelty and Its Link to Recurrent Adult Interpersonal Violence. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 62: 2345–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanser, Shelby H., Kristyn R. Vitale, Lauren E. Thielke, Lauren Brubaker, and Monique Ar Udell. 2019. Spotlight on the psychological basis of childhood pet attachment and its implications. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 12: 469–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wright, Jeremy, and Christopher Hensley. 2003. From animal cruelty to serial murder: Applying the graduation hypothesis. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 47: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, Peter, and Alexandra Iwanski. 2019. Attachment Disorder behavior in early and middle childhood: Associations with children’s self-concept and observed signs of negative internal working models. Attachment & Human Development 21: 170–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).