Abstract

Youth workers are on the front line for supporting children and young people with the violence some of them face. However, education and training for this part of the role seemed lacking in our experience as a Youth and Community Worker and a Youth and Community Work Lecturer in the UK. An international project that sought to address this educational gap for ‘youth practitioners’ had a UK arm, which is the context for this article. This project created a three-day training course that sought to improve responses to gender-related violence (GRV) by increasing awareness, improving knowledge about providing support and making referrals, and also sought to prevent or reduce gender-related violence by challenging the inequalities on which it rests. The UK ‘youth practitioners’ who attended the training wrote almost 500 ‘action plans’—plans to act on the basis of the training, and analysis of these offers an indication of their concerns and priorities. Here, we present the concerns that UK-based teachers and youth workers had for the children and young people they worked with, and the forms of violence they were aware of when they began this training course. We then describe the interventions with young people or changes to their practice that these attendees said they would make in response to the training once they were back at work. This provides an agenda for action in youth, education and social services to address gender-related violence in the lives of children and young people in the UK. By the end of the training, the interventions they had committed to making included changes to their own practice, showing their reflexivity and their understanding that key tools for tackling gender-related violence included their own behaviour and reflexive practice in their service or team. They highlighted the need for culture change at an organisational level, and identified the problems of sexism and homophobia, even in their own workplaces. Their views about the value of the term gender-related violence (GRV) were mixed, with some practitioners finding it unnecessarily theoretical and others finding it a helpful link between areas of discrimination and of violence that they tended to tackle separately, such as between homophobia and violence against women and girls.

1. Introduction

Professionals working with children and young people have an important role in tackling gender-related violence because they are a source of education about gendered and other inequalities, are models for challenging abusive or disrespectful behaviour, and are key to the support of and referrals for those children and young people who experience violence.

Education for gender equality and against violence are sometimes divergent and fail to link abuse and violence relating to gender and sexual orientation to inequalities and cultural norms (Alldred 2013; DePalma and Atkinson 2009; Formby 2015; Monk 2011; Stonewall 2017). The training described here grew out of author 2’s experience of delivering workshops in UK schools on violence against women and girls (VAWG), and on tackling homophobia, as wholly separate initiatives, and of teaching in universities and hearing from student practitioners where they felt professional education needed to be strengthened. The recognition that gender norms function to justify and sustain both types of violence led to a broadly framed project to tackle violence regarding gender and sexual orientation that tried to incorporate norm criticality (Bromseth and Darj 2010) and to present this in a way that was useful to practitioners.

The GAP Work Project (2013–2015) was an EU co-funded (DAPHNE III) Action Project1 to help ‘youth practitioners’—professionals working in everyday roles with children and young people, not necessarily in specialist, violence support services—to tackle gender-related violence in young people’s lives. Partners in Italy, Ireland, Spain, and the UK each developed and piloted their own, locally-contextualised training intervention. Each Partner shared their training resources, and a report of trainees’ responses to the training, and Partners’ own view of its success was published in their own language. This article focuses on the UK arm. The funding was for an Action Project and thus focused on the development of training for professionals, with only limited research capacity, so three PhDs ran alongside. The funded project gathered the ‘Action Plans’ during the training, and Cooper-Levitan’s PhD (forthcoming) reports follow-up interviews with professionals to explore its impact in their organisation.

2. The GAP Work Project in the UK

The UK team adopted the definition of gender-related violence that the project proposed, which was: ‘Sexist, sexualising or norm-driven bullying, harassment, discrimination or violence whoever is targeted. It therefore includes gender, sexuality and sex-gender normativities, as well as violence against women and girls’ (Alldred 2013; and see Alldred and Biglia 2015). This England-based team were supportive of problematising the Gender Order as a whole and felt it addressed their concerns about bullying or homophobia in schools and youth work settings (Seal and Harris 2016). The deconstruction of the normativities relating to sex, sexuality, and gender were put centre-stage in designing the training intervention (Alldred et al. 2014, p. 15). To achieve this, the training design prioritised three thematic areas within this definition. These were: violence against women and children; violence based on ‘LGBT+phobia’; and violence based on ‘machismo’, including violence that is intended to police and enforce hegemonic masculinity (Connell 2005; Lombard 2016; Rivers 2000).

The UK team devised a three-day training programme that included topics such as definitions of gender, violence, and gender-related violence; the law on sexual consent; ‘how to talk about sex and relationships with young people’; and what interventions they could make as ‘youth practitioners’ (outlined in Appendix A). The training had been designed in the bid (Alldred 2013), but the detailed design and training methodology was devised and delivered by Fiona Cullen, Michael Whelan, Neil Levitan (now Mika Neil Cooper-Levitan) and Malin Stenstrom (now Malin Elge), with Whelan leading Day 1, Rights of Women leading Day 2, and Stenstrom leading Day 3. The UK trainers were funded Partners in the project as they were experienced specialists in youth worker education and gender violence,2 and the training resources produced and piloted are all free to download (USVreact/eu). See Cullen and Whelan (2021) for the trainers’ reflections on the experience.

The UK training was developed with youth workers and teachers in mind since these were the student groups the Principal Investigator (Alldred) had been teaching at university and who often had questions about support and referrals. Cooper-Levitan was appointed to the team for their considerable experience as a youth and community worker and in training youth practitioners. In this sense, the project as a whole grew out of imagining what these practitioners might be able to do with relevant education or training, recognising what Initial Teacher Education failed to cover, and knowing what youth and community work practitioners were reporting witnessing amongst the young people they worked with.

The UK team recognized that they were attempting to fit a lot (‘a Gender Studies Masters’) into a three-day educational intervention. It could be accused of using training methodologies despite its learning outcomes reflecting educational intentions (Jones et al. 2021) and it had an ambitious aim to offer theory as a resource for practitioners.

3. The Training Intervention

The training programme began with an overall introduction to the three days, agreeing ground-rules and expectations. The training narrative then moved onto exploring the social construction of gender and the expansive typology of violence that could be considered GRV. It then explored the intersections of gender and violence and its relevance to practice through examples that covered domestic abuse, homophobic bullying, and teenage intimate partner violence. A later activity that helped concretise these issues was a GRV risk assessment process that helped practitioners to explore the link between gender inequality and GRV in their specific organisational contexts.

Workshops were designed to span three days of training, but could be delivered as a 2.5 day package when required by employers.

The aims were to enable practitioners to:

- Recognise gender-related violence (GRV) in their work settings;

- Confidently intervene and take action to combat GRV;

- Support and refer young people to appropriate agencies;

- Disseminate their learning to colleagues.

The purpose of the first day’s workshop was to understand the concept of gender-related violence and its relevance to work with young people. For some participants, this meant it was like a crash course in ‘Feminism 101’ and was an introduction to problematizing gender norms, inequalities, and linking these to violence. The intended learning outcomes were for practitioners to have:

- gained an understanding of the relevance of gender-related violence to their practice;

- considered the significance of language and organisational culture in reinforcing or challenging gender inequalities and GRV;

- identified ways in which gender inequalities and violence are talked about within their practice or work settings; and

- identified areas of risk.

In an ‘Action Planning’ activity, participants identified actions they could undertake at work to respond to or to prevent or reduce GRV, and then at the end of the day a brief survey asked about their learning including their confidence to support children or young people. Before the start of the programme, participants had completed a brief survey that established their informed consent to allow the project to collect their anonymous Action Plans and survey data, in exchange for the training, which was free. We reflect on both the limitations of this consent practice and the feedback about their overall learning journeys and self-identified learning needs elsewhere (Cooper-Levitan and Alldred forthcoming).

The second day’s workshop was called ‘Promoting Healthy Relationships and Understanding the Law’ and was designed with the intention that practitioners would by the end of the day ‘be able to challenge common perceptions about GRV in relation to abusive relationships.’ This day involved participative activities to reflect on children’s emergent sexuality, to identify principles for holding discussions about sex and about relationships with young people, and an in-depth briefing about the law on sexual consent, and mapping legal options for support in relation to domestic abuse, sexual abuse, or sexual harassment. This part of the training was led by Rights of Women and the accessible legal resource Understand, Identify, Intervene: Supporting Young People in Relation to Peer-on-Peer Abuse, Domestic and Sexual Violence produced for this is freely available at https://rightsofwomen.org.uk/get-information/criminal-law/understand-identify-intervene-supporting-young-people-relation-peer-peer-abuse-domestic-sexual-violence/ (accessed on 28 October 2022). Again, at the end of the day, participants identified what actions they could take at work or to improve their professional practice (Action Plan 2), and were again asked to complete a brief survey to reflect on their learning so far.

The third workshop was called ‘Putting it into Practice’ and focused on promoting equality through developing norm critical anti-oppressive practice. It emphasised practice and skills such as communication styles and enabling techniques, with activities designed to apply the discussions to professional practice to recognise individual and cultural differences in interpretation and priorities for relationships or other life decisions, and considered domination techniques and how anti-oppressive practice might gain from understanding these. Again, practitioners were engaged in considering what actions they would be able to implement at work (Action Plan 3), and discussing in the group the activities to combat GRV they had identified in their Action Plans. A more abstract activity was an invitation to reflect on GRV as an effect of power inequalities, and more tangibly, participants reviewed the pre-existing resources they could draw on to support their practice, and helped to evaluate the training by giving their feedback and suggested improvements. Finally, certificates of participation were given out.

Experienced trainers ran the sessions (see Note 1), with at least one researcher present to co-facilitate if necessary and to observe the session. In some cases, both authors and another trainer were present. All the researchers were in fact also trainers, but specific roles were agreed for each session.

The training materials and resources are available to adopt and adapt on www.USVreact/eu (accessed on 10 August 2022) and we welcome reports of their adaptation, use and value in other settings.

4. Analysis of Intended Actions

The training programme described above is subject to a wider study to explore its impact and how practitioners are best supported on this topic (Cooper-Levitan forthcoming). As a feminist-inspired project, all phases of the research process were framed by a critical, intersectional and reflexive approach, which also informed the pedagogies adopted and the team roles. We co-authors are university educators in youth and community work and sociology of gender and sexuality, and a youth educator/trainer with a youth work background, so our analysis is informed by youth work, as well as by our feminist perspectives and the various liberation movements we have been involved with as activists.

This analysis focuses on the attendees’ existing knowledge and concerns, and the actions they intended to take in response to the training. The evaluation of the training focused on ‘action planning’ because the UK team agreed an overarching aim of understanding the impact of the training, both in shaping awareness and aspirations, and the eventual interventions in workplaces, given that aspects of these work contexts might help or hinder the implementation of these actions. Cooper-Levitan’s PhD is a longer-term study of some of the trainees who occupy youth work roles. It uses critical participatory action research to support them to tackle or prevent GRV among the young people they work with. Here, our focus is on understanding the short- to medium-term impact of the training, through participants’ aspirations.

Nearly 200 ‘youth practitioners’ participated in the UK training during the funding period, and by the end of this period, three London Local Authorities were considering a roll-out to entire Youth or Community Safety departments. Professionals booked to attend the training programme and it was delivered in 10 cohorts of 20 people each over three days, usually consecutively, in London or Coventry. In one case, a whole Local Authority (local government) team was booked on as a cohort. All participants completed a consent form for the study at the start of the training programme’s first day and completed the initial survey which gathered information about their role and their existing confidence with the topic of gender violence and VAWG. This is where the information about their ‘concerns’ comes from.

All participants were invited to complete a worksheet on their intentions to make changes or interventions at work (‘Action Plans’) towards the end of Day 1, Day 2, and Day 3 and 190 participants did so. However, since both completing the Action Plans and sharing them with the research team were optional, and because we excluded those participants who did not attend all three days, our set of Action Plans numbers 490 in total. Appendix A (below) summarises the training programme, showing where the Action Plans happened in the programme. An analysis of the actions they had written about on these sheets is described below, showing what hopes and aspirations they had for their subsequent interventions. To contextualise this, we present an indication of their initial awareness and concerns before they completed the training programme and what they wanted to gain from it.

Attendees were, as expected, mostly youth and community workers and teachers, with some social workers. (This was in contrast with the Italian arm of the project, for instance, who mostly trained health professionals). The knowledge or perspectives of experts in a field is recognised as a valuable resource for research since it is the accumulation of the views of multiple professionals, which are each based on their experiences over time and in multiple cases (such as service users or patients in health contexts). The Delphi method (Duffield 1988; Sleet and Dane 1985; cf. Fox 1998) is a method for pooling professional perspectives in this way. Collating the views of the UK youth practitioners about the violence in young people’s lives reflects a Delphi-style method, although they all reported their concerns simultaneously, so this does not include a reflection on each other’s views. The intentions described on the Action Plans were copied into NVIVO and analysed thematically (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Thematic analysis inevitably reflects the concerns of the researcher/s and we recognise that our perspectives shape the themes identified in the data, perhaps here emphasising the educational/learning/pedagogy and equality related themes. We were admittedly invested in the success of the training, and we were (differentially) invested in the concept of GRV too, particularly because at the time it seemed to offer an exciting way of helping norm criticality make it into practice with young people via stand-alone trainings. It is far from an independent evaluation of the training; however, this arm of the project collected multiple types of data to answer its four research questions, and has analysed the survey responses qualitatively and quantitatively (in Alldred et al. 2014). These artefacts of the training method—the Action Plans—have not been analysed previously.

In what follows, we present (1) the concerns these 190 practitioners brought to the training course and (2) the interventions that they designed on the basis of the training. We will discuss whether those participants who were later interviewed reported achieving their intended interventions, and what they and we understood as limiting their capacity to act in Cooper-Levitan and Alldred (forthcoming).

4.1. Professionals’ Concerns

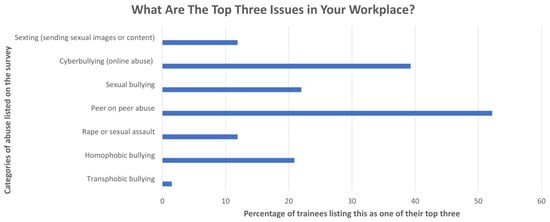

One of the ways to assess professionals’ prior knowledge and understanding of GRV was to ask them what they were worried about. This was included in the initial survey, that was analysed descriptively and is summarised in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

Professionals’ Concerns Regarding Violence in the Lives of the Young People They Worked With.

About half of the UK participants were youth workers, and the remaining half were a mix of teachers and social workers, with a small number of allied health professionals. The Youth and Community Workers were a mixture of trainees, newly qualified, experienced, and middle/senior managerial staff. The teachers were mostly in the final month of Initial Teacher Education (ITE), although there was also a handful of very experienced teachers who were committed to tackling violence. Most of these taught in State secondary schools, although those in primary schools were keen to point out that they saw these issues amongst their pupils too.

When asked in the pre-training survey what issues they had concerns about, and they were allowed to indicate as many as they wished from a list, they most frequently identified peer-on-peer abuse, sexual bullying, online abuse and homophobia, with several identifying concerns over transphobic bullying too. Over half of them pointed to the problem of abuse within peer relationships and recognised their need for education around this. Nearly 70% were attending because they wanted knowledge and skills to intervene in gendered violence, and half of them noted the need to improve their knowledge in order to refer properly into specialist services. What they most wanted to gain from the training was factual information (nearly 90% identified this), methods to use with young people (90%), and communication skills to intervene (75%), but half of them also identified wanting methods to use with colleagues, and to improve their own confidence at tackling these topics (Alldred et al. 2014, p. 69).

The next section examines how training is turned into action by describing what youth practitioners planned to do to tackle gender-related violence, that is, their plans to put their learning into practice—their aspirations. These come from a thematic analysis of the actions they planned to take after the training course.

4.2. Planning to Take Action

‘Action Plans’ were written individually on each day of training on sheets designed to be taken away as prompts. Altogether, 490 Action Plans were gathered over the training programme, and 190 participants altogether provided between them 120 (on day 1), 170 (on day 2), and 200 on day 3. At first, some participants were reluctant to share what they had written, but most became emboldened as they heard what others had thought of and realised that simple ideas might potentially generate bold impacts. Analysis of the practitioners’ Action Plans asked, ‘What plans do you have as a result of this training?’ and ‘What actions have been inspired by and designed on the basis of this training?’

It would be possible to analyse them by participant since anonymous data were awarded a personal identification code to allow them to be linked across elements of the dataset. However, here we are interested in the range and types of professional hopes and plans for interventions prompted by the training or elicited as a result of the focus on (and insight into) GRV. We take this collective ‘To Do’ list as revealing something about the state of play in these professional contexts—in terms of problems identified and types of solutions imagined and proposed. The analysis process followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) data emersion, initial coding of individual items, identification of themes among them, then review and mapping of themes. This process was employed iteratively until all codes and themes contained a coherent narrative. Four main themes were apparent, and these, the sub-themes and some examples of each will be described.

Overall the UK trainees said they planned to act on the training in four main areas: through (1) Interventions—specific new activities with the children or young people they worked with; (2) Organisational change—promoting change in the culture of their organisation itself; (3) Learning about what constituted ‘good practice’; and (4) Reflexive practice—developing their own professional and personal practice.

4.2.1. Interventions

Specific Interventions were the most popular type of action planned, and it had six sub-themes that we called Planned Youth Activities, Classroom Interventions, Parent and Families, Communities, Referral and Punitive. The most commonly planned interventions were specific Planned Youth Activities, which mirrored the vocational make-up of participants (mostly youth workers). This was found on the Action Plans of participants at trainee, practitioner, and managerial levels and was made up of three main types. The most commonly envisaged were training workshops for young people, which was particularly prevalent on practitioner and managers’ Action Plans. This centred on cascading the learning through non-formal awareness-raising workshops for young people. For example, a practitioner wanted to ‘Deliver session to young people to help them know their rights’, another said ‘help them understand the problem with bra-pinging’. The next most common was experiential learning activities which was found more on the Action Plans of trainees and practitioners, unsurprisingly as they do the most groupwork in youth settings—examples included: ‘use story telling techniques to illustrate healthy relationships’ and were sometimes through empathy ‘help them see how this might feel’. Our final code in this subtheme was informal conversations and discussion, which was much more commonly identified on the Action Plans of professionals-to-be (Initial Teacher Education or Youth and Community Work students). An example of this is ‘Help young people to recognise oppression, what it is and how it is perpetrated’.

Classroom interventions planned were of two types: modifications of teaching content and resources, and of the classroom culture. More teachers were concerned to introduce new teaching content and resources, but both aspects featured in the Action Plans of experienced school-based practitioners and trainees. An example of teaching content from an experienced schoolteacher was: ‘Build more on healthy relationships into my assemblies and group work’, and an example of interventions regarding the classroom culture were ‘Ensure my class have an understanding of appropriate behaviour’ and ‘are able to discuss behaviour outside the classroom’.

The remaining subthemes have low prevalence across the dataset but are thematically significant. Parent and Families highlighted preventative work more generally and both of these were found on the Action Plans of teachers and youth workers at all levels of experience, for example, ‘Work with a diverse group of parents to extend understanding to different cultures’. Communities aspirations were about doing preventative work with community leaders and organisations, and this had a high prevalence in the plans of managers in youth settings, for example, ‘Working outreach in socially deprived areas, as gang culture is prevalent in these estates’. Referral to specialist professionals occurred occasionally on the Action Plans, with two elements: ‘Counselling referrals’ and ‘Group therapy referrals’. The final subtheme was Punitive or regulatory actions, which, interestingly, were only found on the plans of youth workers and social workers in institutional settings such as prisons, and not on those of teachers (for instance, ‘Build GRV into behavioural agreements’).

4.2.2. Organisational Change

The next ‘arch-theme’ was (2) Organisational change, and corresponded specifically to aspects of managing organisations. This theme was present mostly on Action Plans from day 1, as this is when we focused specifically on how organisations reflected their values around GRV, in particular, what forms of GRV were ‘acceptable, unacceptable and tolerated’. Participants had identified violence that went unproblematised in their workplace, including the violence and gendered violence in music lyrics, and had shared their insights that while young men’s violence was a common focus of community safety work, there was little critical reflection on police behaviour, and that equality discourses in the organisation might be ‘good on race and religion, but poor on sexual orientation’. Participants identified homophobic undertones and heterosexism as a problem in one of the large organisations booking staff onto the training. This organizational change theme was prevalent at all levels of experience, not only on the Action Plans of managers. For example, Challenging culture was made up of Awareness-raising, which many practitioners and trainees identified as a tangible action, alongside Challenge staff, a code that was popular among managers, for instance ‘Encourage staff to challenge homophobic behaviour when it occurs’.

Training, supervision, and development were combined into one subtheme, and it was prevalent amongst managers and those with responsibility for sessional staff, e.g., ‘Give training to staff using some of these resources’. Policies and procedures was a subtheme made up of things such as ‘Update policies’, ‘Review policies in the workplace and youth organisations policies’ and ‘Ensure GRV is reflected in policy on safeguarding young people’. Curriculum/project development was the fourth type of organizational change planned and these were at system or regional level: ‘provide structured programmes on these issues and assist other youth workers in training so that it can become a part of all youth programmes within [our] youth clubs’.

4.2.3. Good Practice

The third and fourth themes occurred less frequently, although they were still quite popular: Good Practice meant identifying and adopting ‘best practice’ recommendations, which often involved updating resources and refreshing the organisation’s approach. For instance, inter-professional working—a mainstay of UK policy around safeguarding children and young people since the Laming Report (Laming 2003)—which practitioners said they would promote, or specific things such as ‘Making a good practice booklet to use with different local authorities’ and multi-agency working, e.g., ‘Encourage my organisation to build external relationships for support’. In terms of sharing the learning with colleagues, participants had been encouraged to use the project’s award-winning ‘Cascade’ resource (Whelan and Green 2014) and some said they’d ‘Share what I have learned with colleagues in school’.

Finally, participating prompted critical self-reflection and the desire to apply personally some of the tools or challenge domination techniques. The last theme comprises three codes that correspond to Reflexive Practice (4).

4.2.4. Reflexive Practice

Reflexive practice was an aspiration across all levels of experience and in teaching or youth work settings. In terms of teaching practice, teachers said they would ‘Personally think more about gender stereotypes in [my] lesson planning’, in terms of practice with young people, ‘act as a role model for young people’, and in terms of management practice, ‘use enabling techniques to solve problems’.

The UK team were pleased that each of these areas were identified for action and that inter-staff relations and organisational culture were problematised, not only the behaviour of the young people or ‘out there’ beyond the organisation. We hoped to inspire feminist praxis after the training when youth professionals might be able to act. However, to understand what they actually succeeded in doing once back in the workplace, a small number of follow-up interviews were conducted over the following year, which we report elsewhere.

5. Conclusions

An agenda for action in tackling gender-related violence in children and young people’s lives has been identified through pooling the concerns of 190 youth practitioners. UK professionals working with children and young people in generic (not violence-focused) roles were already concerned about peer abuse that might be on or offline, and that might involve sexual bullying or homophobic or transphobic bullying. They also identified organisational culture change as necessary, highlighting as problematic the sexist and homophobic cultures in their own workplaces, and identified their own behaviour and the development of reflexive practice as key tools in tackling gender-related violence (GRV). The number of themes described above is the range of actions they planned, which shows how, after attending the training, these youth practitioners were able to identify a wide range of forms of gender-related violence and were able to identify a fair range of actions through which to tackle them. We have pre-training and post-training self-report data showing significantly improved confidence in their ability to identity and to suggest actions to tackle GRV (with extracts in Alldred et al. 2014).

The actions that practitioners planned to take as a result of the training shows what they both identified as needed in professional work with children and young people or in their workplace or team, and felt enabled to tackle. These addressed the areas of concern they shared at the start of the training course, but also identified new concerns such as homophobia in their team or in popular culture. They commonly planned specific actions in their face-to-face work with young people, but they recognised the value of community level work too, including with the children or young people’s families. The development of organisations and the reflexivity of teams were highlighted as key, not only the development and reflexivity of individuals within them. It was fully recognised that practitioners needed to feel well supported themselves if they were to be able to tackle violence. Reflection on practice was viewed as needing to develop from a critical perspective in order to tackle issues such as GRV (Morley 2014).

In addition to identifying specific actions to take, many practitioners said they benefitted from the training by the increased awareness of, commitment to, and confidence about tackling GRV that was needed in order to be critical about their practice and their organisational culture and dynamics within it. The concern to tackle homophobic behaviour shows that for some participants this wide framework was helpful as it connected problematic behaviour usually addressed separately, for instance, male-to-male abuse (for example, homophobic violence) with male-to-female abuse (such as sexual harassment or IPV). For others, this framework was needless since the examples and illustrations of bullying, harassment, or discrimination ensured their concern and commitment without theoretical justification. So, it seems that the concept of GRV may have been helpful for some participants and for others the point was taken with or without the concept itself. It is possible that the concept was convincing for the more academic trainees, but left some practitioners untouched or at worse, without an easy tool or concept to use. We found a significantly higher impact of the training for teachers than for youth workers or the miscellaneous other youth professionals in the UK arm of the project (Alldred et al. 2014, pp. 75–82).

These findings demonstrate the short– to medium-term impact of the project in England, and helps us to understand how practitioners such as teachers and youth workers can turn learning into interventions and the development of their professional and personal practice. This analysis shows how youth practitioners construct the elements of youth and community work practice (Kemmis et al. 2014), which we would use to reverse-engineer future educational experiences to support them in preventing and responding to GRV in young people’s lives.

In conclusion, what UK-based teachers, youth workers, and other ‘youth practitioners’ felt needed tackling were all issues that we agreed were problematic and we saw as forms of gender-related violence. In fact, they were mostly examples of sexism, misogyny, or gender inequality, and in a few cases they included homophobic and heterosexist practices that we had drawn into our category of GRV. Given that in two cases the practitioners were problematizing their own staff culture as homophobic or heterosexist, we feel that the concept of GRV had successfully broadened the perspective of some of the practitioners.

Against the four intended learning outcomes listed earlier, this wide range of interventions identified suggests that practitioners had: (i) gained an understanding of the relevance of gender-related violence to their practice, and (iv) identified areas of risk, and that their own work practice and team dynamics were problematised suggests many of them had (ii) considered the significance of language and organisational culture in reinforcing or challenging gender inequalities and GRV, and (iii) identified ways in which gender inequalities and violence are talked about within their practice or work settings.

On the basis of their self-reported improved understanding and the meaningful examples of planned actions, we concluded that the training had been of value. What we need to examine next is what these practitioners actually managed to do once they were back in practice settings. This may offer further reflection on the quality of actions identified, and how training can support effective action planning, as well as in the contexts in which these professionals are working currently. We continue to learn about what will help youth practitioners to tackle gender-related violence as we follow their professional successes in later interviews and an action research project (Cooper-Levitan forthcoming).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, P.A. and M.N.C.-L.; software and formal analysis, M.N.C.-L.; data curation, M.N.C.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.N.C.-L. and P.A.; writing—review and editing, P.A.; supervision, P.A.; project administration, P.A.; funding acquisition, P.A.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was co-funded through the European Union’s Daphne-III Programme (code: JUST2012/DAP/AG/3176) and led by Pam Alldred at Brunel University London (UK) between 2013–2015.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Brunel University London (UK) (School of Health & Social Care) Research Ethics Committee on 13 January 2013.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The study did not gain permissions to archive the data.

Acknowledgments

Ian Rivers’ contribution to the GAP Work Project is appreciated here; Gerard Whelan of Brand Central (www.brandcentral.ie, accessed on 10 August 2022) kindly donated his time to the project to design this resource for practitioners to cascade their learning to their colleagues and won a design award for it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

An Overview of the UK GAP Work Project Training Programme.

Table A1.

An Overview of the UK GAP Work Project Training Programme.

| Day | Objective | Overview of Content | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Unpacking ‘Gender-related violence’ (one full day) | To explore the nature of Gender-Related Violence (GRV) and its impact on young people. |

| Understanding intersectional definition of gender-related violence. Knowledge of the impact of GRV on young people in the UK. Understanding of strategies that can be applied. |

| 2. Young People, Respectful Relationships and the Law (one full day) | To explore the meaning of respectful relationships and the legal, professional and ethical duties on youth practitioners to address GRV in their work. |

| Understanding the professional legal framework. Promoting healthy relationships with and amongst young people. Knowledge of strategies to apply to organisational and individual practice. |

| 3. Bringing It All Together (one full day) | To explore how norm critical pedagogy can be applied to practice settings. |

| Knowledge of norm critical pedagogy. Application of norm criticality to practice. Understanding of ways of transferring learning from [anon] training to setting. |

Notes

| 1 | Dr Fiona Cullen lead the UK arm of the project. Neil Levitan (now Mika Neil Cooper-Levitan) was appointed as Researcher on the project, but in fact, agreed a role-share with Trainer, Malin Stenstrom (now Malin Elgh). |

| 2 | Rights of Women are a London-based charity providing legal advice and information to women, as well as working to improve the law for women and increase women’s access to justice. In addition to providing a free legal advice phone-line for women, they offer training for police, social workers, lawyers, etc. https://rightsofwomen.org.uk/about-us/ (accessed on 28 October 2022). Funding via the GAP Work Project enabled the first publication to support young women’s access to justice: https://rightsofwomen.org.uk/get-information/criminal-law/understand-identify-intervene-supporting-young-people-relation-peer-peer-abuse-domestic-sexual-violence/ (accessed on 28 October 2022). About Young People are a Youth Worker training organisation run by Dr Michael Whelan, a qualified, experienced youth worker, who was researching masculinity and violence (Whelan 2013). Both organisations provided trainers for the session and co-designed the training materials. |

References

- Alldred, Pam. 2013. GAP Work Project: Training for Youth Practitioners on Tackling Gender-Related Violence. Bid to the European Union DAPHNE-III Programme. London: Brunel University London Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alldred, Pam, and Barbara Biglia. 2015. Gender-Related Violence and Young People: An Overview of Italian, Irish, Spanish, UK and EU Legislation. Children & Society 29: 662–75. [Google Scholar]

- Alldred, Pam, Miriam E. David, Barbara Biglia, Edurne Jimenez, Pilar Folgueiras, Maria Olivella, Sara Cagliero, Chiara Inaudi, Bernie McMahon, Oonagh McArdle, and et al., eds. 2014. GAP Work Project: Training for Youth Practitioners on Tackling Gender-Related Violence. Project Report. London: Centre for Youth Work Studies, Brunel University London. Available online: www.brunel.ac.uk/people/project101293 (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromseth, Janne, and Frida Darj. 2010. Normkritisk Pedagogik. Makt, Lärande och Strategier för Förändring. Uppsala: Centrum för Genusvetenskap. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, Raewyn W. 2005. Masculinities, 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Levitan, Mika Neil. Forthcoming. Disrupting Entanglements of Gender-Related Violence through the Production of Norm Critical Youth and Community Work Praxis. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Health and Life Sciences, Division of Social Work, Brunel University London, London, UK.

- Cooper-Levitan, Mika Neil, and Pam Alldred. Forthcoming. Department of Social Work, Care and Community, School of Social Sciences, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK. in preparation.

- Cullen, Fiona, and Michael Whelan. 2021. Pedagogies of Discomfort and Care: Balancing Critical Tensions in Delivering Gender-Related Violence Training for Youth Practitioners. Education Science 11: 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePalma, Renee, and Elizabeth Atkinson. 2009. Interrogating Heteronormativity in Primary Schools: The No Outsiders Project Paperback. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, C. 1988. The Delphi technique. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing 6: 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Formby, Eleanor. 2015. Limitations of focussing on homophobic, biphobic and transphobic ‘bullying’ to understand and address LGBT young people’s experiences within and beyond school. Sex Education 15: 626–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Nick J. 1998. The contribution of children to informal care: A Delphi study. Health and Social Care in the Community 6: 204–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, Charlotte, Anne Chappell, and Pam Alldred. 2021. Feminist education for university staff responding to disclosures of sexual violence: A critique of the dominant model of staff development. Gender and Education 33: 121–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemmis, Stephen, Robin McTaggart, and Rhonda Nixon. 2014. The Action Research Planner: Doing Critical Participatory Action Research. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Laming, W. H. 2003. The Victoria Climbie Inquiry: Report of an Inquiry by Lord Laming; London: HMSO (Cm. 5730), ISBN 0101573022.

- Lombard, Nancy. 2016. Young People’s Understandings of Men’s Violence against Women. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Monk, Daniel. 2011. Challenging homophobic bullying in schools: The politics of progress. International Journal of Law in Context 7: 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, Christine. 2014. Using critical reflection to research possibilities for change. British Journal of Social Work 44: 1419–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivers, Ian. 2000. Social exclusion, absenteeism and sexual minority youth. Support for Learning 15: 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seal, Mike, and Pete Harris. 2016. Responding to Youth Violence Through Youth Work. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sleet, David A., and J. K. Dane. 1985. Wellness factors among adolescents. Adolescence 20: 909–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stonewall. 2017. The School Report 2017: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bi and Trans Pupils in Britain’s Schools. London. Available online: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/the_school_report_2017.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Whelan, Michael. 2013. Street Violence Among Young Men in London: Everyday Experiences of Masculinity and Fear in Public Space. Ph.D. thesis, Brunel University London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, Michael, and Laura Green. 2014. GAP Work Practitioner Training ‘Cascade’ Resource. Design: BrandCentral. London: Brunel University London, October, Available online: www.brandcentral.ie (accessed on 10 August 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).