The Link between Family Violence and Animal Cruelty: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Link

1.2. Current Study

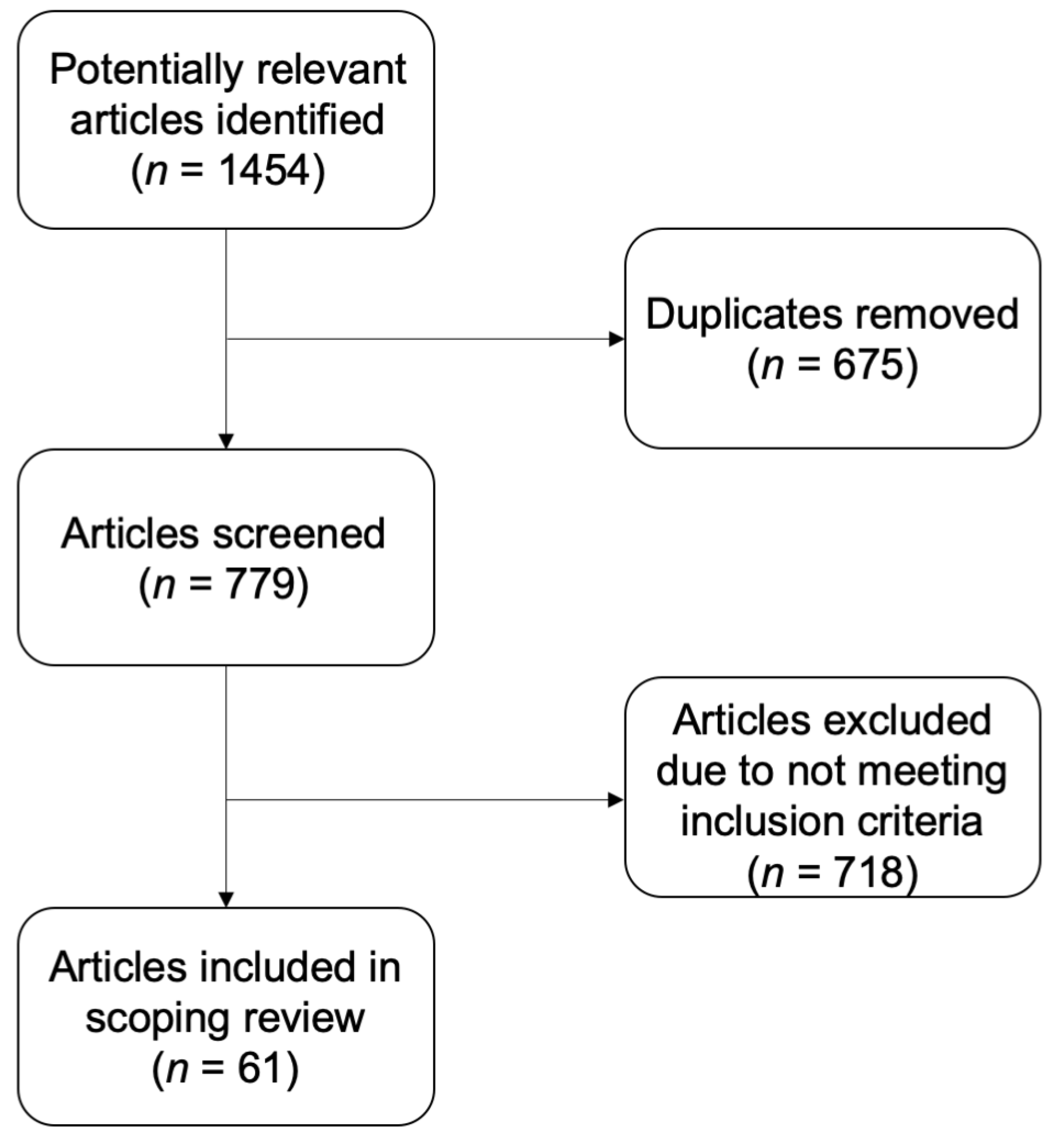

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Parameters

2.2. Screening and Data Charting

2.3. Synthesis of Results

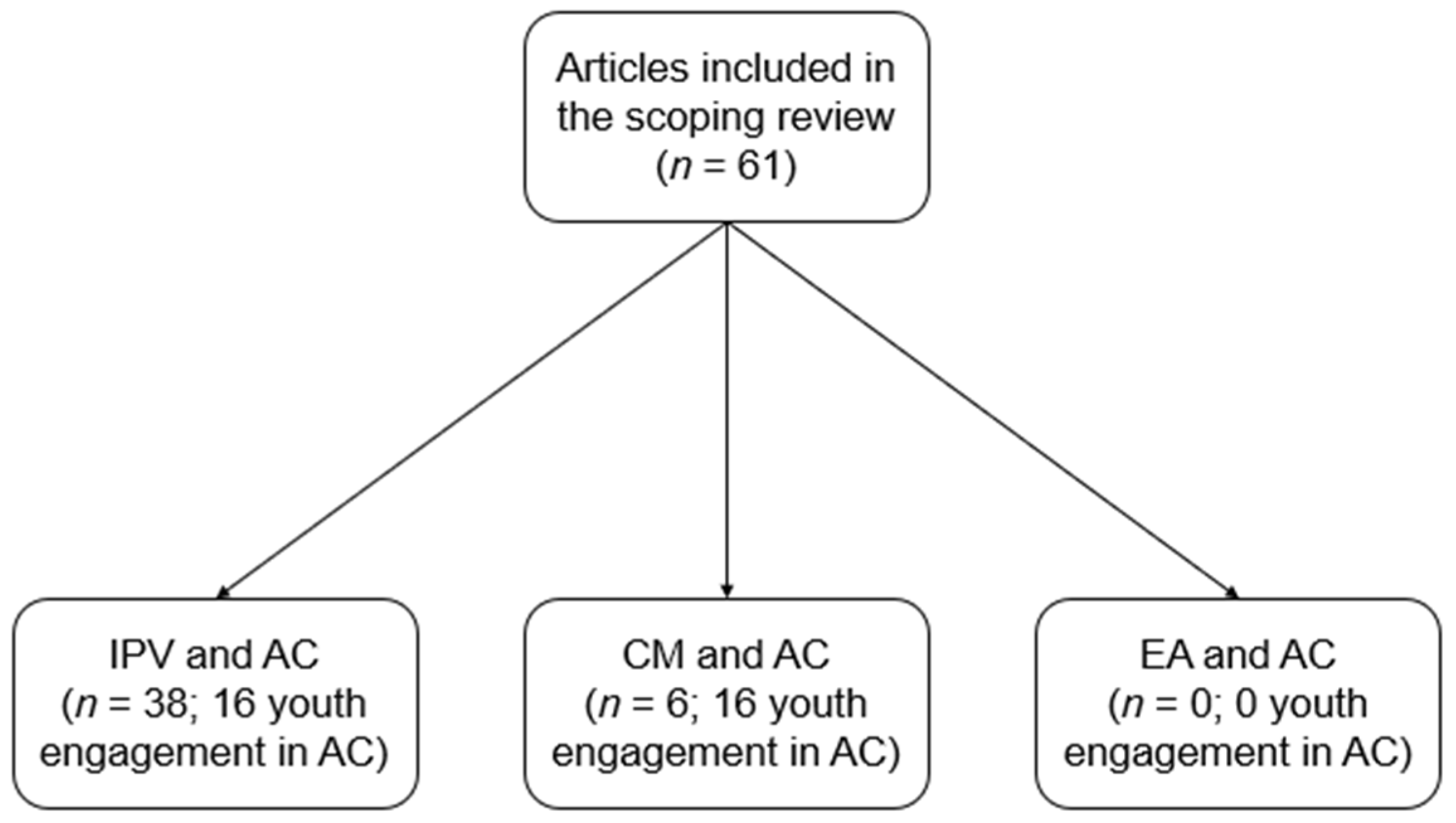

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies

3.2. Intimate Partner Violence and Animal Cruelty

3.2.1. Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence and Animal Cruelty by Adults

3.2.2. Prevalence of IPV and Animal Cruelty by Youth

3.2.3. Relations between IPV and Animal Cruelty by Adults

3.2.4. Relations between IPV Exposure and Youth Engagement in Animal Cruelty

3.3. Child Maltreatment and Animal Cruelty

3.3.1. Prevalence of Child Maltreatment and Animal Cruelty Perpetrated by Adults

3.3.2. Prevalence of Child Maltreatment and Engagement in Animal Cruelty by Youth

3.3.3. Relations between Child Maltreatment and Animal Cruelty Perpetrated by Adults

3.3.4. Relations between Child Maltreatment and Youth Engagement in Animal Cruelty

3.4. Elder Abuse and Animal Cruelty

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of the Available Literature

4.2. Future Directions

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Current Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Some of the IPV studies included samples of women in which some women were less than 18 years of age. They were included in the same sample as adults as they were all receiving domestic violence shelter services. |

| 2 | The articles designated with a superscript 2 all used the same dataset (different than the dataset associated with superscript 3). |

| 3 | The articles designated with a superscript 3 all used the same dataset (different than the dataset associated with superscript 2). |

References

- Arkow, Phil. 2021. ‘Humane Criminology’: An Inclusive Victimology Protecting Animals and People. Social Sciences 10: 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, Hilary, and Lisa O’Malley. 2005. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, Frank R. 1993. Children Who Are Cruel to Animals: A Review of Research and Implications for Developmental Psychopathology. Anthrozoös 6: 226–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, Frank R. 1997. Battered Women’s Reports of Their Partners’ and Their Children’s Cruelty to Animals. Journal of Emotional Abuse 1: 119–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, Frank R., Claudia V. Weber, and David S. Wood. 1997. The Abuse of Animals and Domestic Violence: A National Survey of Shelters for Women Who Are Battered. Society & Animals 5: 205–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, Frank R., Claudia V. Weber, Teresa M. Thompson, John Heath, Mika Maruyama, and Kentaro Hayashi. 2007. Battered Pets and Domestic Violence: Animal Abuse Reported by Women Experiencing Intimate Violence and by Nonabused Women. Violence Against Women 13: 354–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, Frank R., William N. Friedrich, John Heath, and Kentaro Hayashi. 2003. Cruelty to Animals in Normative, Sexually Abused, and Outpatient Psychiatric Samples of 6- to 12-Year-Old Children: Relations to Maltreatment and Exposure to Domestic Violence. Anthrozoös 16: 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwood-Harvey, Dana. 2007. From Touchstone to Tombstone: Children’s Experiences with the Abuse of Their Beloved Pets. Humanity & Society 31: 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglivio, Michael T., Kevin T. Wolff, Matt DeLisi, Michael G. Vaughn, and Alex R. Piquero. 2017. Juvenile Animal Cruelty and Firesetting Behaviour. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health 27: 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldry, Anna C. 2003. Animal Abuse and Exposure to Interparental Violence in Italian Youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 18: 258–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldry, Anna C. 2005. Animal Abuse among Preadolescents Directly and Indirectly Victimized at School and at Home. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health 15: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, Betty Jo, Amy Fitzgerald, Amy Peirone, Rochelle Stevenson, and Chi Ho Cheung. 2018. Help-Seeking Among Abused Women With Pets: Evidence From a Canadian Sample. Violence & Victims 33: 604–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Betty Jo, Amy Fitzgerald, Rochelle Stevenson, and Chi Ho Cheung. 2020. Animal Maltreatment as a Risk Marker of More Frequent and Severe Forms of Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 35: 5131–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, Kimberly D., Jeffrey Stuewig, Veronica M. Herrera, and Laura A. McCloskey. 2004. A Study of Firesetting and Animal Cruelty in Children: Family Influences and Adolescent Outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 43: 905–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boat, Barbara W., Erica Pearl, Jaclyne Barnes, Linda Richey, Denise Crouch, Drew Barzman, and Frank W. Putnam. 2011. Childhood Cruelty to Animals: Psychiatric and Demographic Correlates. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 20: 812–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiding, Matthew J., Kathleen C. Basile, Sharon G. Smith, Michele C. Black, and Reshma Mahendra. 2015. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements; Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/intimatepartnerviolence.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Bright, Melissa A., Mona Sayedul Huq, Terry Spencer, Jennifer W. Applebaum, and Nancy Hardt. 2018. Animal Cruelty as an Indicator of Family Trauma: Using Adverse Childhood Experiences to Look beyond Child Abuse and Domestic Violence. Child Abuse & Neglect 76: 287–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, John A., Christopher Hensley, and Karen M. McGuffee. 2017. Does Witnessing Animal Cruelty and Being Abused During Childhood Predict the Initial Age and Recurrence of Committing Childhood Animal Cruelty? International Journal of Offender Therapy & Comparative Criminology 61: 1850–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Andrew M., Shannon L. Thompson, Tara L. Harris, and Sarah E. Wiehe. 2021. Intimate Partner Violence and Pet Abuse: Responding Law Enforcement Officers’ Observations and Victim Reports From the Scene. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: 2353–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Ko L., Qiqi Chen, and Mengtong Chen. 2021. Prevalence and Correlates of the Co-Occurrence of Family Violence: A Meta-Analysis on Family Polyvictimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 22: 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Elizabeth A., Anna M. Cody, Shelby Elaine McDonald, Nicole Nicotera, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2018. A Template Analysis of Intimate Partner Violence Survivors’ Experiences of Animal Maltreatment: Implications for Safety Planning and Intervention. Violence against Women 24: 452–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, Cheryl L. 2006. Animal Cruelty by Children Exposed to Domestic Violence. Child Abuse & Neglect 30: 425–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGue, Sarah, and David DiLillo. 2009. Is Animal Cruelty a ‘Red Flag’ for Family Violence? Investigating Co-Occurring Violence Toward Children, Partners, and Pets. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 24: 1036–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, Alexander, Jay C. Thomas, and Catherine Miller. 2005. Significance of Family Risk Factors in Development of Childhood Animal Cruelty in Adolescent Boys with Conduct Problems. Journal of Family Violence 20: 235–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrlich, Katherine B., Gregory E. Miller, and Edith Chen. 2016. Childhood Adversity and Adult Physical Health. In Developmental Psychopathology, 3rd ed. Edited by Dante Cicchetti. Hoboken: Wiley, Volume 4, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faver, Catherine A., and Alonzo M. Cavazos. 2007. Animal Abuse and Domestic Violence: A View from the Border. Journal of Emotional Abuse 7: 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faver, Catherine A., and Elizabeth B. Strand. 2003. To Leave or to Stay?: Battered Women’s Concern for Vulnerable Pets. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 18: 1367–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febres, Jeniimarie, Hope Brasfield, Ryan C. Shorey, Joanna Elmquist, Andrew Ninnemann, Yael C. Schonbrun, Jeff R. Temple, Patricia R. Recupero, and Gregory L. Stuart. 2014. Adulthood Animal Abuse among Men Arrested for Domestic Violence. Violence Against Women 20: 1059–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febres, Jeniimarie, Ryan C. Shorey, Hope Brasfield, Heather C. Zucosky, Andrew Ninnemann, Joanna Elmquist, Meggan M. Bucossi, Shawna M. Andersen, Yael C. Schonbrun, and Gregory L. Stuart. 2012. Adulthood Animal Abuse among Women Court-Referred to Batterer Intervention Programs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27: 3115–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felthous, Alan R., and Stephen R. Kellert. 1987. Childhood Cruelty to Animals and Later Aggression against People: A Review. American Journal of Psychiatry 144: 710–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, William J., and Susan J. Plumridge. 2010. The Association between Pet Care and Deviant Household Behaviors in an Afro-Caribbean, College Student Community in New Providence, the Bahamas. Anthrozoös 23: 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, Amy J., Betty Jo Barrett, and Allison Gray. 2021. The Co-Occurrence of Animal Abuse and Intimate Partner Violence among a Nationally Representative Sample: Evidence of ‘The Link’ in the General Population. Violence and Victims 36: 770–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, Amy J., Betty Jo Barrett, Allison Gray, and Chi Ho Cheung. 2022. The Connection Between Animal Abuse, Emotional Abuse, and Financial Abuse in Intimate Relationships: Evidence From a Nationally Representative Sample of the General Public. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: 2331–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald, Amy J., Betty Jo Barrett, Rochelle Stevenson, and Chi Ho Cheung. 2019. Animal Maltreatment in the Context of Intimate Partner Violence: A Manifestation of Power and Control? Violence against Women 25: 1806–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, William, Brian Jory, and David Burton. 2002. Characteristics of Juvenile Offenders Admitting to Sexual Activity with Nonhuman Animals. Society & Animals 10: 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, Clifton P. 1999. Exploring the Link Between Corporal Punishment and Children’s Cruelty to Animals. Journal of Marriage & Family 61: 971–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, Clifton P. 2000a. Battered Women and Their Animal Companions: Symbolic Interaction between Human and Nonhuman Animals. Society & Animals 8: 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, Clifton P. 2000b. Woman’s Best Friend: Pet Abuse and the Role of Companion Animals in the Lives of Battered Women. Violence Against Women 6: 162–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Kelley. 2020. Getting Eyes in the Home: Child Protective Services Investigations and State Surveillance of Family Life. American Sociological Review 85: 610–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, B., M. Allen, and B. Jones. 2008. Animal Abuse and Intimate Partner Violence: Researching the Link and Its Significance in Ireland—A Veterinary Perspective. Irish Veterinary Journal 61: 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbrecht, Crystal J. 2022. Animal Safekeeping in Situations of Intimate Partner Violence: Experiences of Human Service and Animal Welfare Professionals. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP16931–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, Alberta, and Joanna Pozzulo. 2012. The Significance of Animal Cruelty in Child Protection Investigations. Social Work Research 36: 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Peter C., and Eleonora Gullone. 2005. Knowledge and Attitudes of Australian Veterinarians to Animal Abuse and Human Interpersonal Violence. Australian Veterinary Journal 83: 619–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gullone, Eleonora. 2012. Animal Cruelty, Antisocial Behaviour, and Aggression. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haden, Sara Chiara, Shelby E. McDonald, Laura J. Booth, Frank R. Ascione, and Harold Blakelock. 2018. An Exploratory Study of Domestic Violence: Perpetrators’ Reports of Violence against Animals. Anthrozoös 31: 337–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haegerich, Tamara M., and Linda L. Dahlberg. 2011. Violence as a Public Health Risk. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine 5: 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, Christie A., Tina Hageman, James Herbert Williams, and Frank R. Ascione. 2018. “Intimate Partner Violence and Animal Abuse in an Immigrant-Rich Sample of Mother-Child Dyads Recruited From Domestic Violence Programs. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 33: 1030–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, Christie, Tina Hageman, James Herbert Williams, Jason St. Mary, and Frank R. Ascione. 2019. Exploring Empathy and Callous-Unemotional Traits as Predictors of Animal Abuse Perpetrated by Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 2419–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Roxanne D., Shelby Elaine McDonald, Kelly O’Connor, Angela Matijczak, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2019. xposure to Intimate Partner Violence and Internalizing Symptoms: The Moderating Effects of Positive Relationships with Pets and Animal Cruelty Exposure. Child Abuse & Neglect 98: 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, Bill C. 2006. Empathy, Home Environment, and Attitudes toward Animals in Relation to Animal Abuse. Anthrozoös 19: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffer, Tia, Holly Hargreaves-Cormany, Yvonne Muirhead, and J. Reid Meloy. 2018. The Relationship Between Family Violence and Animal Cruelty. In Violence in Animal Cruelty Offenders. Edited by Tia Hoffer, Holly Hargreaves-Cormany, Yvonne Muirhead and J. Reid Meloy. SpringerBriefs in Psychology. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Megan R., Kristen A. Berg, Anna E. Bender, Kylie E. Evans, Julia M. Kobulsky, Alexis P. Davis, and Jennifer A. King. 2022. The Effect of Intimate Partner Violence on Children’s Medical System Engagement and Physical Health: A Systematic Review. Journal of Family Violence 37: 1221–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegatheesan, Brinda, Marie-Jose Enders-Slegers, Elizabeth Ormerod, and Paula Boyden. 2020. Understanding the Link between Animal Cruelty and Family Violence: The Bioecological Systems Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, Star, and Lisa Maloney. 1999. Animal Abuse and the Victims of Domestic Violence. In Child Abuse, Domestic Violence, and Animal Abuse: Linking the Circles of Compassion for Prevention and Intervention. Edited by Frank R. Ascione and Phil Arkow. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, pp. 143–58. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, Kelly E., Colter Ellis, and Sara B. Simmons. 2014. Parental Predictors of Children’s Animal Abuse: Findings from a National and Intergenerational Sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 29: 3014–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krienert, Jessie L., Jeffrey A. Walsh, Kevin Matthews, and Kelly McConkey. 2012. Examining the Nexus between Domestic Violence and Animal Abuse in a National Sample of Service Providers. Violence and Victims 27: 280–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krug, Etienne G., James A. Mercy, Linda L. Dahlberg, and Anthony B. Zwi. 2002. The World Report on Violence and Health. The Lancet 360: 1083–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeb, Rebecca T., Leonard J. Paulozzi, Cindi Melanson, Thomas R. Simon, and Ileana Arias. 2008. Child Maltreatment Surveillance: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements; Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/resources.html (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Lee-Kelland, Richard, and Fiona Finlay. 2018. Children Who Abuse Animals: When Should You Be Concerned about Child Abuse? A Review of the Literature. Archives of Disease in Childhood 103: 801–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, Lacey, Tia A. Hoffer, and Ann B. Loper. 2016. Criminal Histories of a Subsample of Animal Cruelty Offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior 30: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loring, Marti T., and Tamara A. Bolden-Hines. 2004. Pet Abuse by Batterers as a Means of Coercing Battered Women into Committing Illegal Behavior. Journal of Emotional Abuse 4: 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matijczak, Angela, Shelby E. McDonald, Kelly E. O’Connor, Nicole George, Camie A. Tomlinson, Jennifer L. Murphy, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2020. Do Animal Cruelty Exposure and Positive Engagement with Pets Moderate Associations between Children’s Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence and Externalizing Behavior Problems? Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 37: 601–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, Jon, Julie Adams, Donna Douglas, Chris McCurry, and Mick Storck. 1995. Clinical Characteristics Related to Severity of Sexual Abuse: A Study of Seriously Mentally Ill Youth. Child Abuse & Neglect 19: 1245–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Shelby Elaine, Anna M. Cody, Elizabeth A. Collins, Hilary T. Stim, Nicole Nicotera, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2018a. Concomitant Exposure to Animal Maltreatment and Socioemotional Adjustment among Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Mixed Methods Study. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma 11: 353–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Shelby Elaine, Anna M. Cody, Laura J. Booth, Jennifer R. Peers, Claire O’Connor Luce, James Herbert Williams, and Frank R. Ascione. 2018b. Animal Cruelty among Children in Violent Households: Children’s Explanations of Their Behavior. Journal of Family Violence 33: 469–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Shelby Elaine, Elizabeth A. Collins, Anna Maternick, Nicole Nicotera, Sandra Graham-Bermann, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2019. Intimate Partner Violence Survivors’ Reports of Their Children’s Exposure to Companion Animal Maltreatment: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 2627–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Shelby Elaine, Elizabeth A. Collins, Nicole Nicotera, Tina O. Hageman, Frank R. Ascione, James Herbert Williams, and Sandra A. Graham-Bermann. 2015. Children’s Experiences of Companion Animal Maltreatment in Households Characterized by Intimate Partner Violence. Child Abuse & Neglect 50: 116–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Shelby Elaine, Julia Dmitrieva, Sunny Shin, Stephanie A. Hitti, Sandra A. Graham-Bermann, Frank R. Ascione, and James Herbert Williams. 2017. The Role of Callous/Unemotional Traits in Mediating the Association between Animal Abuse Exposure and Behavior Problems among Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. Child Abuse & Neglect 72: 421–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, Fiona S., Terrie E. Moffitt, and Louise Arseneault. 2014. Is Childhood Cruelty to Animals a Marker for Physical Maltreatment in a Prospective Cohort Study of Children? Child Abuse & Neglect 38: 533–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, Katie A., Kerith Jane Conron, Karestan C. Koenen, and Stephen E. Gilman. 2010. Childhood Adversity, Adult Stressful Life Events, and Risk of Past-Year Psychiatric Disorder: A Test of the Stress Sensitization Hypothesis in a Population-Based Sample of Adults. Psychological Medicine 40: 1647–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhedran, Samara. 2009. Animal Abuse, Family Violence, and Child Wellbeing: A Review. Journal of Family Violence 24: 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsalve, Stefany, Fernando Ferreira, and Rita Garcia. 2017. The Connection between Animal Abuse and Interpersonal Violence: A Review from the Veterinary Perspective. Research in Veterinary Science 114: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montminy-Danna, Mary. 2007. Child Welfare and Animal Cruelty: A Survey of Child Welfare Workers. Journal of Emotional Abuse 7: 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Zachary, Micah D. J. Peters, Cindy Stern, Catalin Tufanaru, Alexa McArthur, and Edoardo Aromataris. 2018. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology 18: 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Jennifer L., Elizabeth Van Voorhees, Kelly E. O’Connor, Camie A. Tomlinson, Angela Matijczak, Jennifer W. Applebaum, Frank R. Ascione, James Herbert Williams, and Shelby E. McDonald. 2021. Positive Engagement with Pets Buffers the Impact of Intimate Partner Violence on Callous-Unemotional Traits in Children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP17205-26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, Michelle. 2017. Pets in Danger: Exploring the Link between Domestic Violence and Animal Abuse. Aggression and Violent Behavior 34: 273–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Micah D.J., Casey Marnie, Andrea C. Tricco, Danielle Pollock, Zachary Munn, Lyndsay Alexander, Patricia McInerney, Christina M. Godfrey, and Hanan Khalil. 2020. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 18: 2119–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, Marie Louise, and David P. Farrington. 2007. Cruelty to Animals and Violence to People. Victims & Offenders 2: 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruccelli, Kaitlyn, Joshua Davis, and Tara Berman. 2019. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Associated Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect 97: 104127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillemer, Karl, David Burnes, Catherine Riffin, and Mark S. Lachs. 2016. Elder Abuse: Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Prevention Strategies. The Gerontologist 56 Suppl. 2: S194–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randour, Mary Lou, Martha Smith-Blackmore, Nancy Blaney, Daniel DeSousa, and Audrey-Anne Guyony. 2021. Animal Abuse as a Type of Trauma: Lessons for Human and Animal Service Professionals. Trauma, Violence & Abuse 22: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, Damien W., Nik Taylor, Heather Fraser, Catherine Donovan, and Tania Signal. 2021. The Link Between Domestic Violence and Abuse and Animal Cruelty in the Intimate Relationships of People of Diverse Genders and/or Sexualities: A Binational Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: NP3169-95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, Michael. 1991. The Social Construction of Child Abuse and ‘False Allegations’. Child & Youth Services 15: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, Catherine A., and Peter Lehmann. 2007. Exploring the Link between Pet Abuse and Controlling Behaviors in Violent Relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 22: 1211–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, Elizabeth B., and Catherine A. Faver. 2005. Battered Women’s Concern for Their Pets: A Closer Look. Journal of Family Social Work 9: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Nik, Heather Fraser, and Damien W Riggs. 2019. Domestic Violence and Companion Animals in the Context of LGBT People’s Relationships. Sexualities 22: 821–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timshel, Isabelle, Edith Montgomery, and Nina Thorup Dalgaard. 2017. A Systematic Review of Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Family Related Violence in Refugee Families. Child Abuse & Neglect 70: 315–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiplady, Catherine M., Deborah B. Walsh, and Clive J. C. Phillips. 2018. The Animals Are All I Have. Society & Animals 26: 490–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, Micah D. J. Peters, Tanya Horsley, Laura Weeks, and et al. 2018. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169: 467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turney, Kristin. 2014. Incarceration and Social Inequality: Challenges and Directions for Future Research. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 651: 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unti, Bernard. 2008. Cruelty Indivisible: Historical Perspectives on the Link between Cruelty to Animals and Interpersonal Violence. In The International Handbook of Animal Abuse and Cruelty: Theory, Research, and Application. Edited by Frank R. Ascione. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, Michael G., Qiang Fu, Kevin M. Beaver, Matt DeLisi, Brian E. Perron, and Matthew O. Howard. 2011. Effects of Childhood Adversity on Bullying and Cruelty to Animals in the United States: Findings From a National Sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 26: 3509–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volant, Anne M., Judy A. Johnson, Eleonora Gullone, and Grahame J. Coleman. 2008. The Relationship between Domestic Violence and Animal Abuse: An Australian Study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23: 1277–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Jeremy, and Christopher Hensley. 2003. From Animal Cruelty to Serial Murder: Applying the Graduation Hypothesis. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 47: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Sakiko. 2010. A Comparison of Maltreated Children and Non-Maltreated Children on Their Experiences with Animals--A Japanese Study. Anthrozoos 23: 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilney, Lisa A., and Mary Zilney. 2005. Reunification of Child and Animal Welfare Agencies: Cross-Reporting of Abuse in Wellington County, Ontario. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program 84: 47–66. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Intimate partner violence | “intimate partner violence,” “domestic violence,” “interpartner violence,” “spouse abuse,” “partner abuse,” “family conflict” |

| Child maltreatment | “child abuse,” “child maltreatment,” “child welfare,” “child neglect,” “physical abuse,” “spanking,” “sexual abuse,” “emotional abuse” |

| Elder abuse | “elder abuse,” “elder maltreatment,” “elder neglect,” “adult protective services” |

| Animal cruelty | “animal cruelty,” “animal abuse,” “animal maltreatment,” “pet abuse,” “cruelty to pets,” “pet maltreatment,” “harm to pets,” “abused pets,” “animal neglect” |

| Example search strategy: (“animal cruelty” OR “animal abuse” OR “animal maltreatment” OR “pet abuse” OR “cruelty to pets” OR “pet maltreatment” OR “abused pets” OR “harm to pets” OR “animal neglect”) AND (“child abuse” OR “child maltreatment” OR “child welfare involvement” OR “child neglect” OR “physical abuse” OR “spanking” OR “sexual abuse” OR “emotional abuse”) | |

| Description | Prevalence of IPV and AC | Prevalence of IPV and Youth Engagement in AC | Prevalence of CM and AC | Prevalence of CM and Youth Engagement in AC |

| Paper Number | 1–38 | 1, 3, 17, 24, 37–48 | 8, 20, 49–52 | 8, 39, 41, 44, 48, 50, 54, 55, 59, 61 |

| Papers That Used the Same Dataset (indicated by 2) | 4, 5 | Note: Although statistics (e.g., demographic information, prevalence rates) may differ across studies, these differences should be interpreted with caution as they are mainly due to sample differences. | ||

| Papers That Used the Same Dataset (indicated by 3) | 7, 22, 23, 27–32 | 47 | ||

| Description | Relationship between IPV and AC | Relationship between IPV and Youth Engagement in AC | Relationship between CM and AC | Relationship between CM and Youth Engagement in AC |

| Paper Number | 3, 5–8, 11, 12, 14, 15, 18, 21–23, 25, 27, 31–33, 35, 37, 38 | 40, 41, 44, 46, 48 | 8, 49 | 8, 41, 42, 44, 48, 50, 53–60 |

| Papers That Used the Same Dataset (indicated by 2) | 5 | Note: Although statistics (e.g., demographic information, prevalence rates) may differ across studies, these differences should be interpreted with caution as they are mainly due to sample differences. | ||

| Papers That Used the Same Dataset (indicated by 3) | 7, 22, 23, 27, 31, 32 | |||

| # | Author(s), Year of Publication | Study Population | Methodology | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ascione (1997) | Female domestic violence (DV) victims seeking services at a DV shelter (N = 38; 20–51 years, M = 30.2 years) in the United States (U.S.). | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors | Prevalence: 71% of women with pets reported their partner had threatened to hurt/kill and/or had actually hurt/killed a pet. |

| 2 | Ascione et al. (1997) | 48 domestic violence shelters across the U.S. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; service provider report | Prevalence: The majority of shelters (85.4%) endorsed that women who seek services at their shelter discuss incidents of AC and 63% of shelters endorsed that children at the shelter discuss incidents of AC; 83.3% of shelters endorsed having observed the co-occurrence of DV and AC, and estimates provided of this co-occurrence by shelter staff ranged from <1% to 85% (M = 44%). |

| 3 | Ascione et al. (2007) | DV victims in Utah (U.S.) who received DV shelter services (N = 101 women, 17–51 years, M = 31.7 years; 39 children, M = 9.8 years, 43.6% girls) and a community sample of women (N = 120 women, 19–57 years, M = 32.5 years; 58 children, M = 10.9 years, 44.8% girls). Race/ethnicity of the Shelter group included 68.3% Caucasian, 12.9% Hispanic/Latina, 6.9% Native American, 7.9% African American, 4.0% Other; the community sample included 95.7% Caucasian, 0.1% Asian, 3.4% Native American. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors | Prevalence: Approximately half of DV victims (52.5%) reported threats to hurt/kill pets and 54% reported actual hurting/killing of pets by their partner. In contrast, only 12.5% of the community sample reported threats to hurt/kill pets and 5% reported actual hurting/killing of pets by their partner; 11.1% and 2.5% of DV victims and community members reported committing AC, respectively. Other Results: Significant predictors of partners threatening to hurt/kill pets included minor physical violence by partner, verbal aggression by partner, and the woman’s reported level of education. In contrast, the significant predictors of partners actually hurting/killing the pet included membership in the shelter group (vs. non-shelter group) and severe physical violence by partner. Dichotomizing women’s exposure to violence into “no violence” and “any violence” suggested that women exposed to any minor and/or severe physical violence by their partner were more likely to report their partner had threatened their pet and/or hurt their pet in comparison to those not exposed to violence in both the shelter group (threatened: 55.9% vs. 16.7%; hurt: 56.5% vs. 16.7%) and non-shelter group (threatened: 33.3% vs. 7.4%; hurt: 8.7% vs. 3.2%). |

| 4 | Barrett et al. (2018) 2 | Female residents (N = 86) of 16 battered women’s shelters in Canada (M = 37.9 years, SD = 10.89 years; 85.9% heterosexual, 3.5% bisexual, 1.2% lesbian, 3.5% asexual, 5.9% other sexual orientation; 62.8% White, 4.7% Black, 18.6% First Nations or Metis, 7% Arab, 1.2% South Asian, 2.3% Latin American, 3.5% mixed racial/ethnic heritage) | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors | Prevalence: 89% of women reported that their partner had threatened to harm and/or had actually harmed their pet. Specifically, 64.2% reported emotional abuse of animal, 71.2% reported their partner had threatened to harm pet, 48.1% reported physical neglect of pet, 69.8% reported physical abuse, and 25% reported severe physical abuse of the animal. |

| 5 | Barrett et al. (2020) 2 | Participants were women receiving services from domestic violence shelters in Canada (N = 86) who did not have companion animals (N = 31, M = 33.29 years, SD = 9.16 years), who had companion animals with no/low levels of animal abuse (N = 21, M = 41.48 years, SD = 11.79 years), and who had companion animals with severe/high levels of animal abuse (N = 34, M = 39.94 years, SD = 10.61 years). The majority of women in each group were heterosexual (92.86%, 85%, 93.75%, respectively) and were predominantly White (41.94%, 80.95%, 70.59%, respectively). | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account by IPV service recipients | Prevalence: ~89% of women who had pets reported animal cruelty by their partner. The most serious forms of pet abuse included injury to the pet (20%), killing of the pet (14.5%), drowning of the pet (9.1%). Other Results: Animal cruelty scores were positively correlated with all subscales of the Conflict Tactics Scale 2: Severe psychological abuse, minor physical abuse, severe physical abuse, and severe sexual abuse, and the subscales of the Checklist of Controlling Behaviors: Physical abuse, sexual abuse, and economic abuse. There were also significant differences in IPV scores between women without pets (G1), women with pets who suffered no/low levels of animal abuse (G2), and women with pets who suffered severe animal abuse (G3). Specifically, G1 and G3 reported higher levels of severe psychological abuse in comparison to G2. G3 experienced significantly higher levels of minor physical abuse and severe physical abuse in comparison to G2. There were no other significant differences. With regard to controlling behaviors, G3 reported significantly higher scores on physical abuse and sexual abuse in comparison to G2; G1 reported higher scores on sexual abuse compared to G2; G3 reported more economic abuse compared to G1. |

| 6 | Campbell et al. (2021) | Secondary data of domestic violence incident reports (N = 3416 reports, 3476 victims, 3477 suspects) collected by first responders in Marion County, Indiana (U.S.) between 9 November 2014 and 12 February 2015. Among those with a history of animal abuse, suspects ranged in age from 15 to >55 years and were White (49%), African American (49%), and Hispanic (2%), and were predominantly male (96%). Victims were predominantly female (95%), ranging in age from 15 to >55 years. The majority of victims were White (68%), followed by African American (27%) and Hispanic (4%). | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand accounts by IPV survivors following a domestic violence incident | Prevalence: 3% of domestic violence victims also endorsed that the perpetrator had a history of animal cruelty. Other Results: Domestic violence suspects with a history of animal cruelty were significantly more likely to have previously victimized the IPV victim previously, although unreported, compared to those without a history of animal cruelty (80% vs. 60%), and were more likely to have had multiple unreported IPV incidents. Additionally, IPV suspects with a history of animal cruelty more frequently: Followed or spied on the IPV victim (70% vs. 33%), controlled the victim’s activities (84% vs. 55%), forced the victim to have sex (26% vs. 8%), strangled the victim (76% vs. 47%), threatened to kill the victim (63% vs. 31%), and threatened to kill the victim and/or their children (70% vs. 33%) in comparison to those without a history of animal cruelty. Law enforcement officers reported differences in victims’ demeanors based on whether the IPV suspect had a history of animal cruelty or not. For example, when the DV suspect had a history of animal cruelty, officers reported more victims appeared afraid (63% vs. 42%), apologetic (15% vs. 5%), nervous (48% vs. 33%), had visible bruising (35% vs. 20%), complained of pain (63% vs. 52%), and were removed to a temporary safety location such as a DV shelter or medical facility (44% vs. 24%). |

| 7 | Collins et al. (2018) 3 | Participants were women in the U.S. who were IPV survivors, recruited from community-based domestic violence programs (N = 103, age range: 21–56 years, M = 36.62 years, SD = 7.54 years). The racial/ethnic composition of the sample included 52.4% White, 33% Hispanic/Latina, 1.9% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 1.9% African American or Black, 1% Asian, and 8.7% bi/multi-racial women. | Cross-sectional, qualitative; first-hand accounts of IPV survivors | Prevalence: 75% of women reported their partner had threatened their companion animal, 66% reported their partner had harmed their companion animal, and 11% reported the animal was killed. Other Results: 4 themes were identified through template analysis regarding how women and their children experience animal cruelty within the household with co-occurring IPV: (1) Animal maltreatment used as a tactic of coercion and control by the partner (20.4%), (2) animal maltreatment used to discipline or punish the animal (39.8%), (3) youth engagement in animal maltreatment within the home (23%), and (4) exposure to animal maltreatment had an emotional and psychological impact. An additional theme was identified related to companion animals and animal cruelty influencing the decision to stay with/leave the abusive partner. Pets were a barrier to safety planning (38%). |

| 8 | DeGue and DiLillo (2009) | A sample of college students from 3 universities in California, Nebraska, and Ohio (U.S.) were recruited (N = 860). The average age was 20.1 years (SD = 1.72). The majority of students were female (75.6%) and White (70.1%), although the sample also included 11.2% Asian, 7.1% Hispanic/Latino, and 4.2% Black students. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; retrospective reports of exposure to IPV, child abuse, and AC in childhood | Prevalence: Although 22.9% of the sample reported being exposed to animal cruelty, only 5% reported experiencing both domestic violence and animal cruelty as a child (0.9% domestic violence and animal abuse only; 4.1% DV, animal cruelty, and child maltreatment); 36.2% of the sample reported no exposure to family violence (i.e., IPV, child abuse) or animal cruelty. Other Results: Witnessing and/or engaging in animal cruelty during childhood significantly predicted the odds of family violence exposure (OR = 1.48–2.11); however, exposure to domestic violence was not a significant predictor of either witnessing or engaging in animal cruelty when also accounting for child maltreatment. |

| 9 | Faver and Cavazos (2007) | A sample of IPV survivors were recruited from community-based domestic violence programs in Texas (U.S.) who also reported living with a pet (N = 151). All participants were women, ranging in age from 17–59 years (M = 31 years, SD = 9.22 years). The sample was primarily Hispanic (74%), with 14% non-Hispanic White participants, 1% belonging to another racial/ethnic group, and 11% with an unknown race/ethnicity. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand accounts of IPV survivors | Prevalence: 98% of women reported having a pet while in an abusive relationship. Of those, 36% reported their partner had threatened, harmed, and/or killed their pet. There was a non-significant difference in the prevalence of animal cruelty in the sample based on race/ethnicity: 52.4% of non-Hispanic White women vs. 32.4% of Hispanic women. |

| 10 | Faver and Strand (2003) | A sample of 61 women were recruited from IPV shelters in a southeastern U.S. state, although only 41 participants provided complete data and were included in the analysis. Women from the 2 rural shelters ranged in age from 21–54 years (M = 36.6 years, SD = 10.2 years) and included 40% of women from minoritized racial/ethnic groups. Women from the 4 urban shelters were on average 35.8 years old (range: 19–72 years, SD = 13.1 years) and were predominantly White (12.5% minoritized racial/ethnic identities). | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand accounts of IPV survivors | Prevalence: Of the women who provided data regarding animal cruelty, 48.8% endorsed that their partner had threatened their pet and 46.3% reported that their partner had harmed their pet. |

| 11 | Febres et al. (2012) | Participants included 87 women from a Rhode Island (U.S.) court-referred Batterer Intervention Program (M = 30.5 years, SD = 10.27 years). The majority of participants were non-Hispanic Caucasian (74.7%), followed by African American (6.9%), Hispanic (8.0%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (2.3%), Asian/Pacific Islander (1.1%), and Other (5.7%). | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account of IPV perpetrators | Prevalence: Since turning 18 years of age, 15% of women reported engaging in animal cruelty, with an average of 8.8 acts of animal cruelty (SD = 14.3). There were no statistically significant differences in the frequency of IPV between women who endorsed committing acts of animal cruelty and those who did not endorse animal cruelty. Other Results: Animal abuse scores were significantly and positively associated with severe physical assault in this sample; however, they were not significantly correlated with overall (i.e., minor and severe) psychological aggression, overall physical assault, or severe psychological aggression. There were also no statistically significant differences in frequency of IPV based on whether the participant had also engaged in animal abuse or not. |

| 12 | Febres et al. (2014) | Participants included 307 men arrested for domestic violence and court-referred to Rhode Island (U.S.) Batterer Intervention Programs (M = 33.1 years, SD = 10.2 years). Participants identified as non-Hispanic Caucasian (72.3%), African American (12.1%), Hispanic (8.1%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (2.0%), Asian or Pacific Islander (1.3%), and other racial/ethnic identities (3.9%). | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account of IPV perpetrators | Prevalence: 41% of males reported engaging in animal cruelty at least once since turning 18 years of age, with an average of 9.52 acts of animal cruelty. Other Results: Animal abuse scores were weakly (rs < 0.2) and positively associated with self-reported use of psychological aggression, severe psychological aggression, physical assault, severe physical assault, and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) and alcohol use (AUDIT) scores. In a regression model, after controlling for the effects of ASPD and alcohol use, engagement in animal cruelty was no longer significantly associated with severe psychological aggression or severe physical assault. |

| 13 | Fielding and Plumridge (2010) | The sample included college students in New Providence in the Bahamas (N = 641). The majority of student participants were <21 years of age (63.2%) and were female (69.6%). No information regarding race/ethnicity was provided. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account of IPV and AC by a general college sample | Prevalence: 47.3% of participants reported having pets in the home. Of those, 21.3% reported the pet had been harmed on purpose and 20.9% reported IPV. In homes where a pet had been harmed on purpose, 55.6% of women reported that the same person who harmed the animal also was responsible for IPV. |

| 14 | Fitzgerald et al. (2019) | Women recruited from Canadian DV shelters (N = 55) participated in this study. Their age ranged from 21–66 years (M = 40.5 years, SD = 10.99 years). The majority of women (85.5%) were heterosexual, 5.5% were bisexual, 3.6% were asexual, and 5.5% endorsed a different sexual orientation and/or did not respond. Women were predominantly White (74.5%), followed by: 9.1% First Nations, 5.5% Metis, 1.8% South Asian, 5.5% Arab, 1.8% Latin American, and 1.8% mixed racial/ethnic heritage. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors | Prevalence: The majority of women in this sample (89.1%) reported their partner had also abused their pets. Severe forms of abuse included injury to pet (20%), killing pet (14.5%), drowning pet (9.1%). Other Results: This study examined predictors of different forms of animal cruelty (i.e., emotional animal abuse, threats to harm pets, physical animal neglect, physical animal abuse, and severe physical animal abuse) controlling for age, race, and various types of IPV (e.g., psychological aggression, physical assault, sexual coercion). To varying degrees across each analysis, predictors of animal cruelty included (a) maltreatment to upset the participant and/or their children, (b) maltreatment to regain control over a situation, (c) maltreatment to exert power over the participant, and (d) maltreatment had been planned in advance. |

| 15 | Fitzgerald et al. (2022) | This study used data from the 2014 Canadian General Social Survey (N = 17.950), which is a nationally representative survey of Canadian citizens. The survey samples individuals over the age of 15 (M = 49.70 years). Participants included approximately equal numbers of males (n = 8960) and females (n = 8990). The majority of the sample were White (n = 14,920). | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand account by a general sample | Prevalence: Animal cruelty co-occurred with emotional abuse (86.67%), being called names or put down by partner (85%), having contact with close others limited by their partner (45%), and financial abuse (47.62%). Other Results: There were significant differences between those who reported violence against animal companions (VAAC) and those who did not report VAAC for all forms of emotional and financial IPV assessed. Those who had experienced emotional abuse were more likely to have also experienced VAAC (86.67%) in comparison to those who had not experienced emotional abuse (13.42%). In comparison to those who had not experienced VAAC, partners of those who had experienced VAAC were more likely to have had their contact with friends/family limited (52.38% vs. 4.12%), been called names and/or verbally put them down (85% vs. 7.06%), had close friends/family threatened and/or harmed (45% vs. 0.96%), had their possessions damaged (60% vs. 1.98%), and have experienced financial abuse (47.62% vs. 2.49%). In a logistic regression analysis controlling for gender, age, household income, disability status, racial identity, and geographic location (i.e., rural / urban), VAAC significantly increased odds of emotional abuse by 38.6% and financial abuse by 7.5%. |

| 16 | Flynn (2000a) | 10 IPV survivors were sampled from a domestic violence shelter in the U.S. Women ranged in age from 22–47 years. The majority of women were White (n = 8), one was African American, and one was Hispanic. | Cross-sectional, qualitative; first-hand accounts by IPV survivors | Prevalence: The qualitative study explored women’s experiences of animal cruelty within the context of IPV. Women described their companion animals as members of their family that influenced their decision to stay/leave the relationship. Women also reported on their experiences of animal cruelty. Eight of the ten women described their pets were threatened and/or abused by their partner. Animal cruelty was used as a tactic of power and control by their partner. Participants also discussed how their children had witnessed animal cruelty (n = 4 of 7 women with children). |

| 17 | Flynn (2000b) | The sample included 107 women who had received services at a South Carolina (U.S.) DV shelter. Women’s ages ranged from 17–61 years (M = 32.4 years), and race/ethnicity included 59.8% White, 36.5% Black, 2.8% Hispanic, and 1.9% Asian. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand accounts by IPV survivors | Prevalence: Among women with pets, 46.5% reported that their partner had threatened to harm and/or actually harmed their pets. |

| 18 | Gallagher et al. (2008) | The sample included women who were currently receiving or who had previously received DV shelter services at a refuge in the Republic of Ireland (N = 23). No other demographic information was included for this sample. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; first-hand accounts by IPV survivors | Prevalence: Approximately half of the sample (56%) reported that their partner had threatened and/or actually harmed their companion animals through physical abuse and/or neglect; 50% of women also reported that their child had witnessed the animal cruelty. Other Results: Of the 13 women who had experienced animal maltreatment, 12 (92.3%) reported that they believed their pet was maltreated by their partner as a method of controlling them or their children. Other reasons included revenge or anger. |

| 19 | Giesbrecht (2022) | This study included a sample of Canadian human service professionals (e.g., domestic violence shelter/services, police agencies; n = 128) and animal welfare professionals (e.g., veterinary clinics, animal rescues; n = 43). No specific information was provided regarding participants’ age, sex/gender, or race/ethnicity. | Cross-sectional; mixed methods; report by service providers | Prevalence: 65% of human service professionals (i.e., 75% of victim service workers, 69% of domestic violence shelter and service workers, 56% of legal professionals (e.g., attorneys), and 33% of police officers) reported working with survivors of IPV whose animals (i.e., pets, service animals, livestock) had been abused and/or neglected. Approximately half of animal welfare professionals (56%) also reported responding to incidents in which both animal cruelty (i.e., abuse, neglect) and abuse of humans was co-occurring within the home. |

| 20 | Green and Gullone (2005) | 185 Australian veterinarians participated in this study; 58.8% were male, 41.2% were female. The veterinarians’ ages were reported in ordered ranges: 20–29 years (n = 24, 13.0%), 30–39 years (n = 54, 29.3%), 40–49 years (n = 59, 32.1%), 50–64 years (n = 44, 23.9%), and 65+ years (n = 3, 1.6%). No information was provided regarding their race/ethnicity. | Cross-sectional; quantitative; report by service providers | Prevalence: On average, the veterinarians reported animal abuse cases at a rate of 0.12 per 100 animals seen in the clinic. They estimated that 20% of animal abuse had suspected (17.8%) or known (5.9%) co-occurring human abuse, and 53.8% of those cases involved spousal abuse and 25.6% involved abuse of both the spouse and child(ren) in the home. |

| 21 | Haden et al. (2018) | This study included a sample of 42 male participants who were incarcerated in a U.S. Department of Corrections prison and had a history of IPV. The participants’ ages ranged from 21–55 years (M = 37.4 years, SD = 8.27 years), and the majority were White (76.2%), with fewer reporting racial/ethnic identities such as Black/African American (9.5%), Hispanic/Latino (9.5%), or other racial/ethnic group (4.8%). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; report by IPV perpetrators | Prevalence: Within this sample of incarcerated male participants with a history of IPV, 16 (38.1%) had threatened to hurt their partners’ pet during their relationship and 22 (52.4%) had actually hurt and/or killed their partners’ pet. Other Results: 15 (35.7%) of participants also reported animal cruelty as a child. This group of participants (in comparison to those who had not engaged in animal cruelty in childhood) reported higher psychological aggression scores (21.53 vs. 18.18) and sexual coercion scores (5.73 vs. 2.59). There were no significant differences for negotiation, physical aggression, severe sexual coercion, injury, or severe injury scores. Additionally, those who had engaged in animal cruelty as a child were more likely to have threatened animal abuse in a relationship (n = 16 vs. 0) and to have actually abused animals in a relationship (n = 21 vs. 1) in comparison to those who did not abuse animals in childhood. |

| 22 | Hartman et al. (2018) 3 | 291 women (ages 21–65 years, M = 36.6 years, SD = 7.43 years) in the U.S. who had experienced IPV in the past year, had at least one child between the ages of 7 and 12 years living in her home, and had at least one pet in their home in the past year were recruited from domestic violence agencies. One child between the ages of 7 and 12 years (M = 9.07 years, SD = 1.6 years; 47.4% girls) were also selected to participate in the study. The race/ethnicity of the mothers included White (26.9%), Hispanic (60.7%), Black (3.4%), Pacific Islander (0.3%), Asian (0.3%), American Indian/Alaskan (1.7%), and mixed race (6.6%), and their children were: White (22.0%), Hispanic (55.3%), Black (3.4%), Asian (0.3%), American Indian/Alaskan (1.0%), and mixed race (17.9%). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors and their children | Prevalence: Of the 291 women included in this study, 11.7% reported that their partners had threatened to harm a family pet, while 26.1% reported their partners had actually harmed and/or killed the pet. Similarly, 26.2% of the children in the study reported that their mom’s partner had harmed and/or killed a pet. Other Results: Adjusting for income, partner’s level of education, and other forms of IPV, higher psychological aggression scores were associated with higher odds of threats to harm pet (OR = 1.07). In an analysis examining the relationship between IPV and actual harm to pets, psychological aggression scores (OR = 1.02) and partners with more education (OR = 1.22) were associated with greater odds of actual harm to pets controlling for other forms of IPV and income; whereas physical aggression was associated with lower odds of harm to pets (OR = 0.89). However, when adding in the partner’s Hispanicity, no significant association was found between IPV and threats of harm to pets; in examining actual harm to pets, physical aggression (OR = 0.90) and Hispanic Mexican-born partners (OR = 0.26) were associated with lower odds and psychological aggression (OR = 1.07) was associated with higher odds of actual harm. |

| 23 | Hawkins et al. (2019) 3 | This study included a sample of 204 mother-child dyads who were recruited from 22 domestic violence agencies in the western United States between 2010 and 2016. Eligibility criteria included maternal age of 21 years or older, experienced IPV in the past year, had at least one child between the ages of 7 and 12 years in their home, and had either a dog and/or cat in their home within the past year. This study focused on the youth included in the overarching study. Youth ranged in age from 7–12 years (M = 9.11 years, SD = 1.63 years); 52.9% of the sample was male. Youth’s race/ethnicity included Latinx/Hispanic (57.4%), White/non-Hispanic (22.5%), multi-racial (16.2%), Black/African American (2.9%), Asian (0.5%), and American Indian/Alaska Native (0.5%). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; maternal report of youth’s exposure to AC | Prevalence: Among the sample of IPV survivors and their children, 26% of mothers reported that their child had been exposed to animal cruelty by their partner, including threats to harm the pet and actually harming and/or killing the pet. Other Results: Exposure to IPV was not significantly associated with exposure to animal cruelty (r = −0.04). |

| 24 | Krienert et al. (2012) | This study recruited domestic violence service organizations using a directory of U.S. DV programs; 767 domestic violence shelters responded to the survey. On average, the participating shelters served 480 clients in the 6 months prior to participating in the study. Almost 40% of shelters were located in the Midwest. No further sample information was provided. | Cross-sectional; mixed methods; report by service providers | Prevalence: 95.5% of shelters reported having observed DV cases in which animal abuse was present. Across all DV cases seen by the shelter, they estimated that 36.0% of DV cases had co-occurring animal abuse present. Additionally, 93.7% of shelters reported that women seeking services within their organization talked about animal abuse. |

| 25 | Levitt et al. (2016) | 150 criminal records were reviewed of adult males arrested for animal cruelty, animal neglect, and/or animal sexual abuse between 2004 and 2009 in the U.S. Ages of offenders ranged from 18–69 years (M = 37.4 years, SD = 13.2 years), and the majority were Caucasian (n = 102, 68%), followed by African American (n = 25, 17%), Hispanic (n = 12, 8%), Asian (n = 5, 3%), and Native American (n = 3, 2%). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; case review | Prevalence: Among the male offenders arrested for animal cruelty, approximately 20% (n = 30) were also arrested for physically assaulting their spouse/intimate partner. Other Results: The study also examined motives for animal abuse. At least 8% (n = 12) reported abusing an animal in order to retaliate against another person, and of those 58% (n = 7) had been previously arrested for DV and 32% (n = 9) of those who abused a pet belonging to an intimate partner reported doing so to retaliate against their partner. Chi-square results suggest that there was also a significant relationship between participants who had been arrested due to DV assaulted their spouse/intimate partner and participants who had committed animal cruelty. |

| 26 | Loring and Bolden-Hines (2004) | The sample included 107 female IPV survivors who were recruited from a family violence center. Women’s ages ranged from 16–73 years (M = 31 years). The majority of women were Caucasian (63%), followed by African American (22%), Hispanic (11%), Asian (2.5%), and Native-American (1.5%). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors | Prevalence: In this sample, 62% reported having a pet in the home in the past year and/or currently. Of those women, 75% reported animal cruelty (e.g., kicked, hit with fist/object, thrown against a hard object). In all cases of animal cruelty, pets were actually abused and multiple threats of future abuse of the pet occurred. |

| 27 | Matijczak et al. (2020) 3 | This study included the same sample as Hawkins et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional; quantitative; maternal report of youth’s exposure to AC | Prevalence: Prevalence estimates match Hawkins et al. (2019): 26% of mothers reported that their child had been exposed to animal cruelty by their partner. Other Results: Exposure to IPV was not significantly associated with exposure to animal cruelty (r = −0.04). |

| 28 | McDonald et al. (2015) 3 | This study included 58 youth in the U.S. who were interviewed at baseline regarding their experiences of animal cruelty within the context of IPV between their mother and her partner. Youth in this study were all between the ages of 7 and 12 (M = 8.98 years, SD = 1.58 years; 55% female). Youth’s race/ethnicity included Native American or Alaska Native (1.7%), African American or Black (1.7%), White (36.2%), Latino or Hispanic (31%), and more than one race (29.3%). | Cross-sectional; qualitative; first-hand report by youth whose mothers were IPV survivors | Prevalence: In this subsample of youth who participated in the qualitative interview, approximately 38% reported that their pet had been hurt or killed by their mother’s partner, 27% reported experiencing threats of harm to their pet, and 35% reported experiencing both threats and actual animal abuse (i.e., pet was harmed and/or killed). Through thematic analysis, almost half of youth (n = 29/58) identified that animal cruelty was used as a tactic by their mother’s abusive partner as a method of control, while some (n = 14/58) reported that forms of animal cruelty were used to punish the pet. |

| 29 | McDonald et al. (2017) 3 | This study included the same sample as Hartman et al. (2018). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; first-hand report by IPV survivors and reports of their children’s exposure to AC | Prevalence: In this sample, 76% of women reported that their intimate partner had threatened (i.e., 3%), harmed/killed (i.e., 56%), or had threatened to harm and had actually harmed/killed their pet (17%). A quarter of women also reported that their child had witnessed (seen and/or heard) the animal cruelty within the context of IPV co-occurring in the home. |

| 30 | McDonald et al. (2018a) 3 | This study included a sample of 291 mother-child dyads who met the following criteria: Mother was at least 21 years old, had at least one child between the ages of 7 and 12 years, and had a family pet in the home in the past year. All women included in the sample had experienced IPV and lived in the U.S. Mothers were on average 37 years old (SD = 7.89), and the youth participating in the study was on average 8.91 years (SD = 1.57; 49% female). Mothers’ race/ethnicity included White (54.1%), Hispanic (24.3%), Multi-racial (14.9%), Black (1.4%), Asian (1.4%), American Indian/Alaska Native (1.4%), and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (1.4%). The majority of children were White (41.9%), followed by multi-racial/ethnic (32.4%), Hispanic (20.3%), African American (2.7%), Asian (1.4%), and Native American or Alaska Native (1.4%). | Cross-sectional; mixed methods; maternal report of youth socioemotional functioning and interview data from both mothers and youth regarding their experiences with AC | Prevalence: This study identified three underlying subgroups of youth based on their socioemotional functioning: (a) Resilient group, (b) struggling group, and (c) severely maladjusted group. Among the 191 youth in the resilient group, 28 mothers (14.7%) reported that the youth had been exposed to animal cruelty; 48.2% of youth in the struggling group (n = 83) and 41.2% of youth in the severely maladjusted group (n = 17) were reported by their mothers to have witnessed animal cruelty in the home. The subgroups identified were then condensed into asymptomatic and emotional / behavioral difficulties groups. Qualitative data from mothers and youth were used to provide more specific information about youths’ exposure to animal cruelty. The majority of youth within the asymptomatic group were exposed to mild violence against animals (67%), with some exposure to mild/severe threats of violence (44%). In contrast, youth within the emotional and behavioral difficulties group primarily had been exposed to severe violence against animals (81%) and severe threats of violence (30%). |

| 31 | McDonald et al. (2019) 3 | This study included 65 women from a U.S. domestic violence shelter with a child who had been exposed to animal cruelty within the home. Women ranged in age from 21–56 years (M = 36.45, SD = 7.70) and youth ranged in age from 7–12 years (M = 8.97, SD = 1.52; 43% girls). Women’s race/ethnicity included non-Latina White (58.5%), Hispanic/Latina (24.6%), multi-racial/ethnic (12.3%), African American or Black (1.5%), and Asian (1.5%). Youth were primarily non-Latina/o White (46.2%), followed by multi-racial/ethnic (29.2%), Latino/Hispanic (21.5%), African American or Black (1.5%), Asian or American Indian (1.5%). | Cross-sectional; qualitative; maternal report of their child’s experience of AC within the context of IPV | Prevalence: Within the larger study that this sample was derived (N = 291), 29% of mothers reported that at least one of their children had witnessed animal cruelty (i.e., animal abuse, killing of pet). The current study identified more specific detail regarding youth’s exposure to animal cruelty within the home; 90.7% of the current sample (n = 59 of 65) reported that their children had experienced animal cruelty through directly witnessing threats of and actual violence against animals by their partner. Other Results: In the qualitative analysis, mothers reported that one reason for animal maltreatment by their partners was as a method to control the child (n = 8, 12.30%). |

| 32 | Murphy et al. (2022) 3 | This study included the same sample as Hawkins et al. (2019). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; maternal report of youth’s exposure to animal cruelty. | Prevalence: The current study reports that 27% of mothers reported that their child had been exposed to animal cruelty by their partner. Other Results: Exposure to IPV was not significantly associated with exposure to animal cruelty (r = −0.04). |

| 33 | Newberry (2017) | This study collected stories of animal abuse occurring within a domestic violence relationship from public, online discussion forums. (No specific location information was provided in the study). Stories were reported from the victims’ perspective. In total, 74 stories were used in this analysis. | Cross-sectional; qualitative; self-report | Other Results: Thematic analysis resulted in four main themes. Of these themes, one provided information regarding why animal cruelty may co-occur within a domestic violence relationship. Forum stories suggest that companion animal abuse is used as a method to control IPV victims. This was accomplished by using threats and or harm of pets to keep the victim isolated, to maintain financial control, and to coerce the victim to remain in, or return to, the relationship. |

| 34 | Riggs et al. (2021) | This sample included 503 adults in Australia (AUS, n = 258) and the United Kingdom (UK, n = 244) with diverse gender identities and sexual orientations. Participants ranged in age from 18–81 years (M = 39.40 years, SD = 30.04 among AUS participants, M = 38.45 years, SD = 12.46 among UK participants). Among AUS participants, 57.3% identified as female, 29.0% were male, and 10.9% were nonbinary; among UK participants, 63.9% were female, 22.5% identified as male, and 10.7% were nonbinary. Of those who responded, 17.8% of AUS and 20.5% of the UK sample reported “ever identifying as trans.” Participants also reported their sexual orientations: lesbian (AUS: 35.7%; UK: 32.4%), gay (AUS: 26.4%; UK: 18.4%), bisexual (AUS: 14.0%; UK: 28.7%), pansexual (AUS: 11.6%; UK: 11.1%), asexual (AUS: 2.3%; UK: 0.4%), queer (AUS: 7.76%; UK: 6.1%), and heterosexual (AUS: 1.6%; UK: 2.9%). Australian participants reported their Indigenous status as Aboriginal (2.3%), Torres Strait Islander (0.4%), or neither (94.6%). UK participants reported their ethnicity as Asian (1.2%), Black/Caribbean/African (0.4%), Chinese (0.8%), Mixed ethnic group (1.6%), or White (94.3%). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; first-hand account by a general sample | Prevalence: Prevalence of IPV varied by type of abuse: Emotional abuse (40.55%), physical abuse (23.06%), sexual abuse (16.50%), financial abuse (11.33%), and identity abuse (20.27%). Among participants who endorsed experiencing IPV, 21.0% had also experienced the abuse of their animal companion by their partner. Other Results: There were no statistically significant differences in animal cruelty experiences based on gender identity or sexual orientation. |

| 35 | Simmons and Lehmann (2007) | This study included 1283 women who received services at a domestic violence shelter in an urban area of Texas (U.S.) between 1998 and 2002, and who reported having a pet in the home where IPV occurred. No further information regarding age, gender identity, sexual orientation, and race/ethnicity were provided. | Cross-sectional; quantitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors | Prevalence: In this sample, 25% (n = 323) of women reported that their partner had also perpetrated animal cruelty. Other Results: The results of a chi-square analysis found a significant relationship between those who reported their partner had abused their pet and IPV, such that more participants who endorsed animal abuse also endorsed their partner’s use of sexual violence, marital rape, emotional violence, and stalking. However, there was not a significant relationship between the presence of animal abuse and human physical violence. There were also significant differences across all IPV measure subscales (i.e., physical abuse, sexual abuse, isolation, minimization/denial, blaming, intimidation, threats, male privilege, emotional abuse, and economic abuse) and total scores based on whether the partner had abused animals. Positive correlations were also found between the extent of animal abuse and all IPV measure subscales. |

| 36 | Strand and Faver (2005) | 51 women who were receiving domestic violence shelter services in the U.S. were included in this study. Women’s ages ranged from 22–57 years (M = 38 years, SD = 9.22). The majority of the sample was White (57%), followed by Black (18%), Hispanic (8%), Asian (2%), and unknown (16%). | Cross-sectional; mixed methods; first-hand account by IPV survivors | Prevalence: Out of the 51 women in this study, 84% reported having pets while in their abusive relationship; 74% reported that their partner had threatened to harm their pet, 52% reported that their pet had actually been harmed, and 14% reported that their pet had been killed. In sum, 86% of women who lived with a pet during their abusive relationship endorsed that their partner had threatened, harmed, and/or killed their pet. |

| 37 | Tiplady et al. (2018) | This sample included 13 women who were victims of domestic violence, had lived with a pet during that relationship, and had received services through a Queensland, Australia domestic violence service/refuge. Participants ranged in age from 20–55 years (M = 39.08). Of the participants, 2 were noted to be Indigenous and 1 was reported to be English. No further information regarding race/ethnicity, gender identity, or sexual orientation was provided. | Cross-sectional; qualitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors | Prevalence: In this sample, 8 women (61.5%) reported that their pets had been abused and/or neglected by their abusive partner. Types of abuse included verbal (n = 7), physical abuse (n = 7), and neglect (n = 6). Other Results: In their interview, women also described reasons for their partners’ animal abuse: (a) To control/punish the animal, (b) to increase the animal’s “toughness”, and (c) to intentionally upset them. |

| 38 | Volant et al. (2008) | 204 participants were recruited from domestic violence services in Victoria, Australia (n = 102) and from the community without domestic violence experience (n = 102). Women in the DV sample ranged in age from 23–66 years (M = 38.50 years, SD = 9.48 years), and women from the community ranged in age from 18–74 years (M = 42.06 years, SD = 13.25 years). No further information regarding gender identity, sexual orientation, or race/ethnicity were reported. | Cross-sectional; quantitative; first-hand account by IPV survivors and a general community sample | Prevalence: Among women who had experienced DV, 53% reported having at least one dog and 40% had at least one cat. Similarly, 58% of women recruited from the community without DV experience reported having had at least one dog and 49% had at least one cat; 52.9% of women in the DV group reported their partner had abused a pet and 46% reported their partner had threatened to harm their pet. Types of pet abuse reported by the women included the pet being kicked, punched/hit, thrown, choked/suffocated, shot, and stabbed; 29% of women in the DV group reported that their children had witnessed their partner abusing the pet. In contrast, no women in the community group reported pet abuse by their partner and only 5.8% reported their partner had threatened to harm the pet. Other Results: The results of a logistic regression suggest that those with a partner who had threatened to harm their pet were 5x more likely to be in the DV group than those whose partner had not threatened their pet, adjusting for age, number of children, education level, and relationship status. |

| # | Author(s), Year of Publication | Study Population | Methodology | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ascione (1997) | Female domestic violence (DV) victims seeking services at a DV shelter in the U.S. (N = 38; 20–51 years, M = 30.2 years). | Cross-sectional, quantitative; maternal report | Prevalence: Of the 38 women included in this study, 22 had children; 32% of mothers (n = 7) reported that one of their children had hurt or killed a pet. Of these, 5 (71%) reported that their partner had also threatened to or actually hurt or killed the pet. |

| 39 | Ascione et al. (2003) | This study included maternal report for 1433 youth ranging in age from 6–12 years. Youth were then split into 3 groups: A normative group sampled from medical clinics in Rochester, Minnesota and daycare centers in Los Angeles, California (n = 540), a group who had been sexually abused referred from 13 U.S., Canadian, and European clinics (n = 481), and a group of youth participating in a psychiatric outpatient group recruited from 6 clinics in the U.S. and 1 clinic in Germany (n = 412). No other sample demographic information was available (e.g., gender/sex, race/ethnicity). | Cross-sectional; quantitative; maternal report | Prevalence: No statistics for prevalence of animal cruelty among the normative group was available in this study. Among the group of youth who had experienced sexual abuse, mothers who reported the presence of physical fighting between parents also reported that 23.1% of boys and 20% of girls committed animal cruelty. When mothers reported that youth were exposed to both physical fighting between parents and physical abuse victimization, the rates of animal cruelty increased to 36.8% for boys and 29.4% for girls. For youth who were receiving psychiatric services, mothers who reported physical fighting between parents reported that 12.1% of boys had committed animal cruelty. When youth in this group had been exposed to both physical fighting between parents and physical abuse victimization, the rate of animal cruelty by the youth increased to 60% for boys. Mothers did not report any instances of animal cruelty engagement by girls when either physical fighting between parents was present and/or when both physical fighting between parents and physical abuse victimization were endorsed. |

| 3 | Ascione et al. (2007) | DV victims in Utah (U.S.) who received DV shelter services (N = 101 women, 17–51 years, M = 31.7 years; 39 children, M = 9.8 years, 43.6% girls) and a community sample of women (N = 120 women, 19–57 years, M = 32.5 years; 58 children, M = 10.9 years, 44.8% girls). Race/ethnicity of the Shelter group included 68.3% Caucasian, 12.9% Hispanic/Latina, 6.9% Native American, 7.9% African American, 4.0% Other; the community sample included 95.7% Caucasian, 0.1% Asian, 3.4% Native American. | Cross-sectional, quantitative; maternal report and youth self-report | Prevalence: Among the group receiving DV shelter services, 37.5% of mothers reported that one of their children (i.e., not just the youth included in the study) were reported to have hurt or killed a pet, and 10.5% of youth who participated in the study had hurt or killed a pet. In contrast, 11.8% of mothers in the community sample reported that one of their children had hurt or killed a pet. Among youth in the DV group, 13.2% of youth admitted to hurting and/or killing pets during their interview. |

| 40 | Baldry (2003) | This study included a sample of 1396 youth recruited from a random selection of schools in Rome, Italy. Youth ranged in age from 9–17 years (M = 12.1 years, SD = 2.6 years) and were approximately evenly split between girls (45.9%) and boys (54.1%). No information was provided regarding the youth’s race. | Cross-sectional; quantitative; youth self-report | Prevalence: The majority of youth (81.9%) reported having had a pet and/or currently living with a pet, and approximately half of youth (50.8%) reported having engaged in at least one form of animal cruelty (e.g., hitting). Significant differences were found based on gender: 66.5% of boys endorsed animal cruelty vs. 33.5% of girls. The proportion of youth who engaged in animal cruelty varied based on exposure to domestic violence. For example, 44.2% of youth who had not been exposed to DV reported having abused animals, while 58.2% of youth who had been exposed to DV reported having been cruel to animals. Youth exposed to physical DV and threats of violence (67.3% vs. 46.8%), father-to-mother DV (58.7% vs. 44.4%), physical father-to-mother DV and threats (67.3% vs. 47.5%), mother-to-father DV (59.6% vs. 45.6%), and mother-to-father DV and threats (67.5% vs. 48.5%) more frequently endorsed animal cruelty. Other Results: Youth who were exposed to DV were 1.7 times more likely to abuse animals than their peers who were not exposed to DV. Parental animal cruelty perpetration was also associated with greater odds of youth animal cruelty (father OR = 3.1, mother OR = 4.0). Among youth who had been exposed to IPV and child maltreatment, older age, being male, parental animal cruelty, peer animal cruelty, and mother-to-father violence were positively associated with youth engagement in animal cruelty; among youth who had only been exposed to IPV, only being male, parental animal cruelty, and peer animal cruelty were significantly and positively associated with youth engagement in animal cruelty. |

| 41 | Baldry (2005) | A sample of 532 youth recruited from 5 elementary and middle schools in Rome, Italy was included in this study. Participants included 268 girls (50.38%) and 264 boys (49.62%) who were on average 11.8 years (SD = 1.01 years). No information was provided regarding the youth’s race. | Cross-sectional; quantitative; youth self-report | Prevalence: In this sample, youth who had been exposed to parental DV were more likely to abuse animals. Specifically, youth exposed to father-to-mother violence more frequently endorsed animal cruelty in comparison to youth not exposed to this type of DV (59.2% vs. 33.1%) and 60.3% of youth exposed to mother-to-father violence reported being cruel to animals in comparison to 33.9% of youth not exposed to mother-to-father violence. Other Results: Youth exposed to IPV by their father or mother were approximately 3x as likely to engage in animal cruelty in comparison to their peers not exposed to IPV. However, accounting for other forms of victimization/violence (e.g., school victimization), IPV exposure was no longer significantly associated with animal cruelty. |