The Emotional Dimension of the Spanish Far Right and Its Effects on Satisfaction with Democracy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Emotions as a Social Construct and Their Role in Explaining Voting Behaviour

3. The Rise of the Far Right and Its Threat to Democracy

4. Research Methodology

5. Constructing the Explanation to the Rise of VOX

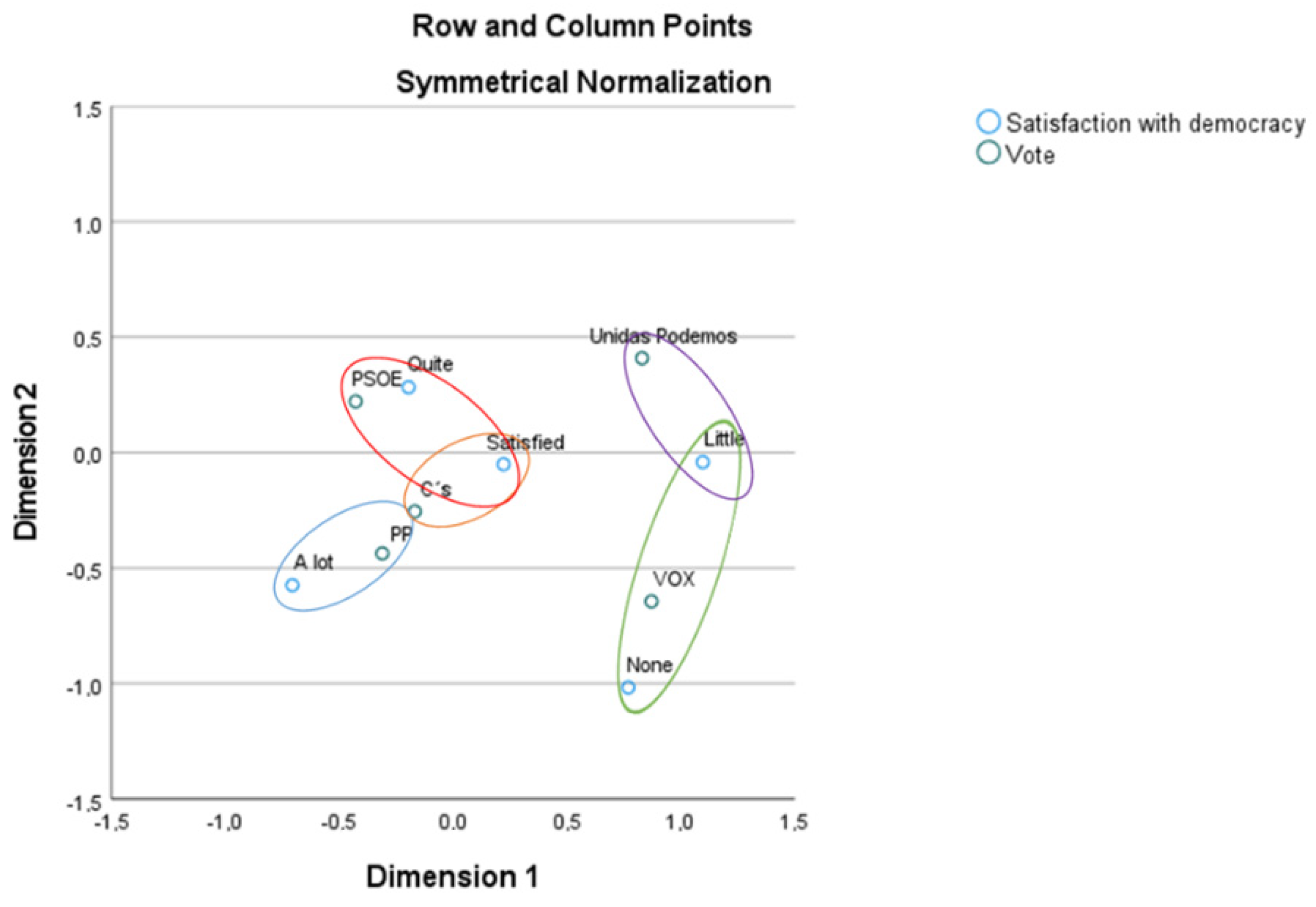

5.1. The Construction of the Vote for VOX

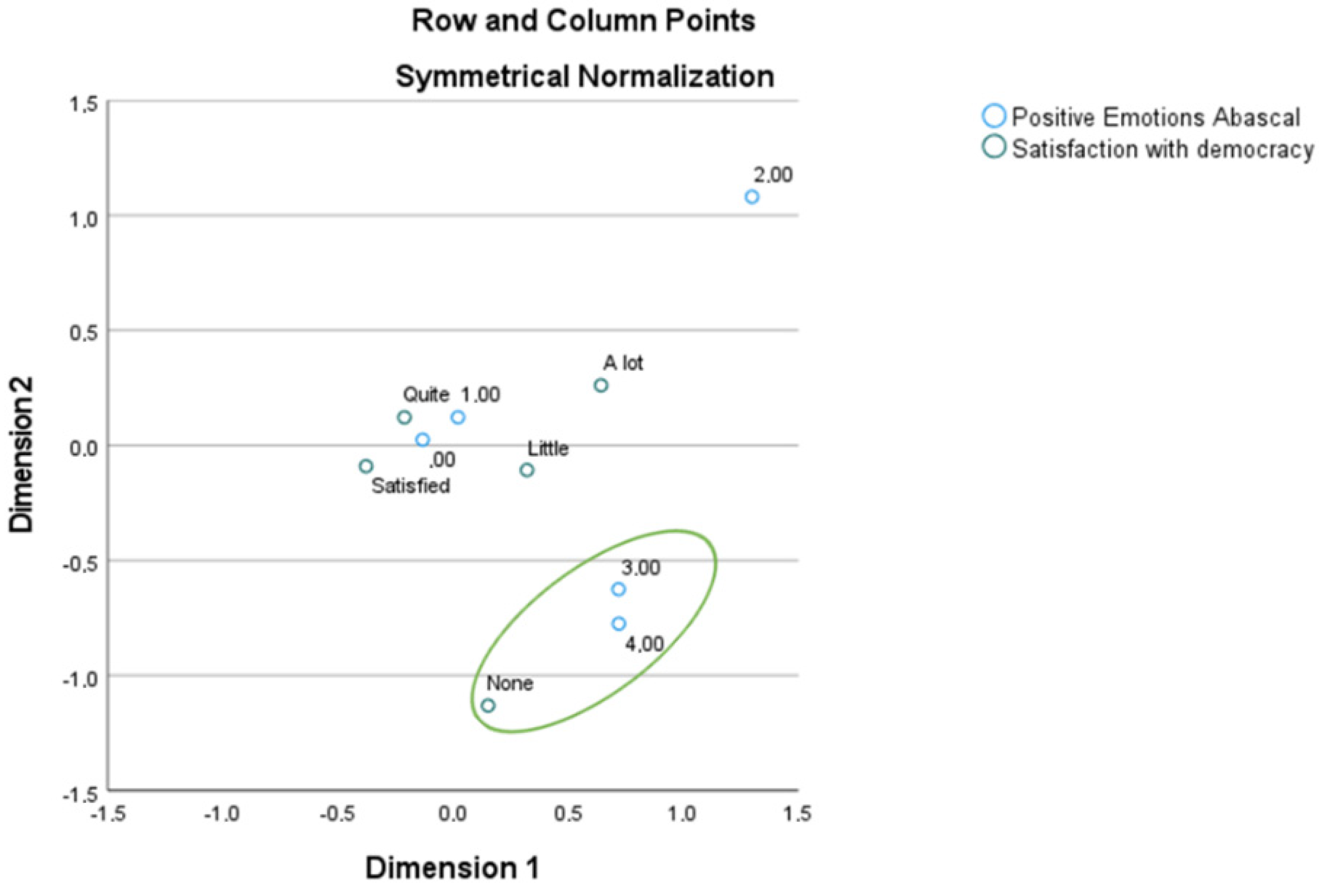

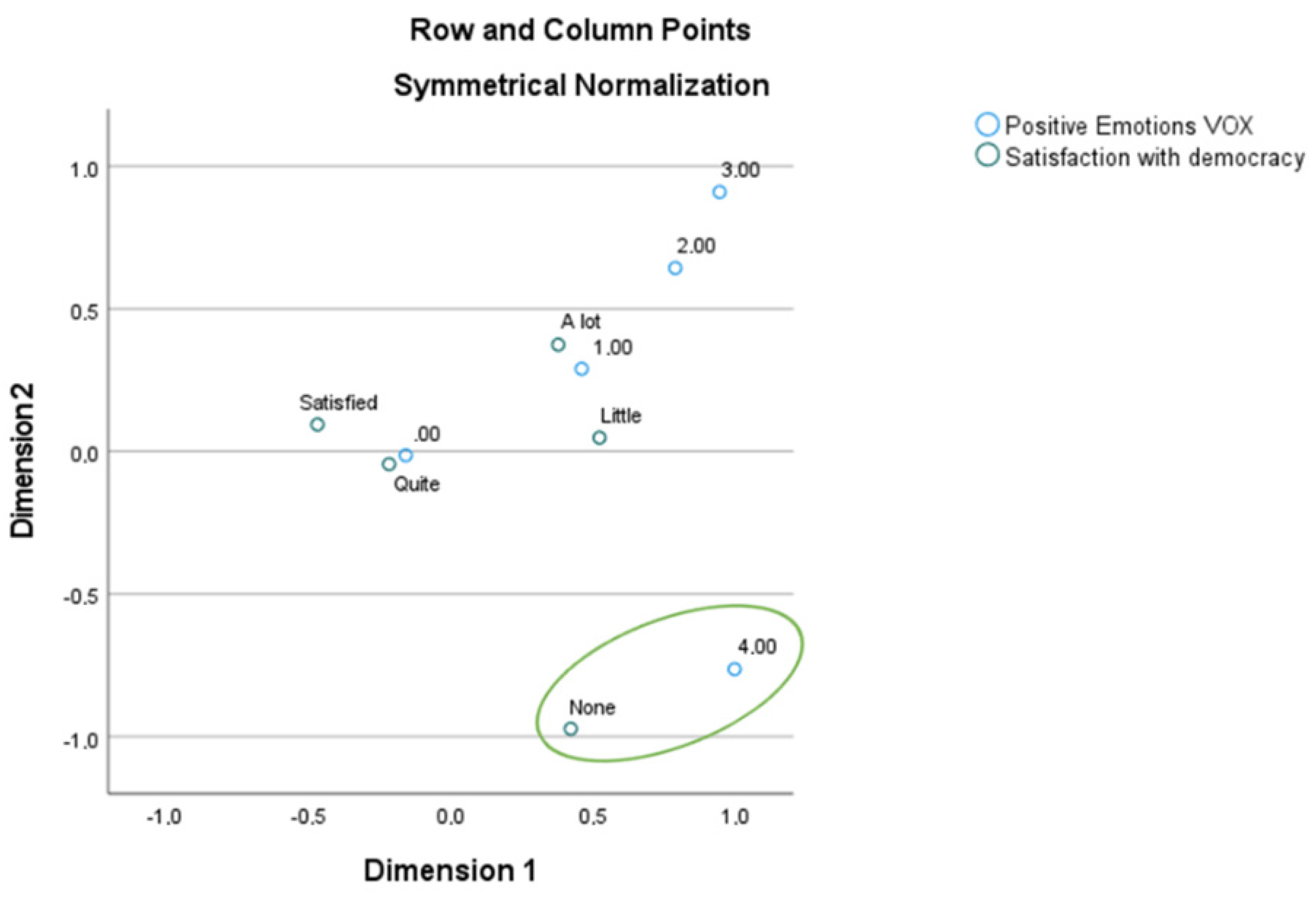

5.2. The Construction of Hope for Santiago Abascal

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Type | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| VOX vote | Nominal (dummy) | 1: VOX–0: Other parties |

| Socio-demographic and contextual | ||

| Gender | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Male–0: Female |

| Age | Quantitative | 0–98 |

| Level of education | Ordinal | 1: Uneducated–6: University |

| Interest-bearing assets | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Interest-bearing assets 0: Other employment situation |

| Interest-bearing liabilities | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Interest-bearing assets 0: Other employment situation |

| Non-interest-bearing assets | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Interest-bearing assets 0: Other employment situation |

| Level of household income | Ordinal | 1: Up to EUR 300–10: +EUR 6000 |

| Catholics | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Catholics 0: Other religious affiliation |

| Rating personal economic sit. | 0: Really bad–10: Really good | |

| Rating current economic sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Rating prospective economic sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Rating current political sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Rating prospective political sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Attitudinal, issues and post-materialist values | ||

| Ideological self-placement | Quantitative | 0: Left–10: Right |

| Nationalist self-placement (Autonomous Communities) | Quantitative | 0: Minimal nationalism–10: Maximum nationalism |

| Spanish nationalist self-placement | Quantitative | 0: Minimal nationalism–10: Maximum nationalism |

| Spanish sentiment | Ordinal | 1: Only Spanish–5: Only from Autonomous Community |

| Independence | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Independence 0: Other issues |

| Sexual freedom | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| European integration | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Trust in political establishment | Quantitative | 0: No trust–10: Maximum trust |

| Trust in democratic institutions | Quantitative | 0: No trust–10: Maximum trust |

| Representation of interests | Quantitative | 0: None–10: A lot |

| Satisfaction with democracy | Quantitative | 0: None–10: A lot |

| Multiculturalism—Immigration | Quantitative | 0: Multiculturalism–10: Immigration |

| Public services—Taxes | Quantitative | 0: Public services–10: Taxes |

| Freedom—Safety | Quantitative | 0: Freedom–10: Safety |

| Populism | ||

| Will of the people | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| People’s decisions | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Differences elite—people | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Representation of ordinary citizen | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Politicians talk too much | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Consensus | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Disaffection | ||

| Search for interests | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Complex politics | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Lack of worry | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Influence of vote | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Informed | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Disaffection | Quantitative | 0: No disaffection–10: A lot of disaffection |

| Interest in politics | Quantitative | 0: No interest–10: A lot of interest |

| Leadership | ||

| Rating political leaders | Quantitative | 0: Very bad–10: Very good |

| Sympathy and emotions | ||

| Sympathy towards VOX | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Sympathy towards VOX 0: Other parties |

| Emotional presence | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Presence of emotion 0: Absence of emotion |

| Variable | Type | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of hope for Abascal | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Presence of hope 0: Absence of hope |

| Structural elements | ||

| Gender | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Male–0: Female |

| Age | Quantitative | 0–98 |

| Level of education | Ordinal | 1: Uneducated–6: University |

| Interest-bearing assets | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Interest-bearing assets 0: Other employment situation |

| Interest-bearing liabilities | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Interest-bearing assets 0: Other employment situation |

| Non-interest-bearing assets | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Interest-bearing assets 0: Other employment situation |

| Level of household income | Ordinal | 1: Up to EUR 300–10: +EUR 6000 |

| Catholics | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Catholics 0: Other religious affiliation |

| Attitudes towards politics and institutions | ||

| Trust in political establishment | Quantitative | 0: No trust–10: Maximum trust |

| Trust in democratic institutions | Quantitative | 0: No trust–10: Maximum trust |

| Representation of interests | Quantitative | 0: None–10: A lot |

| Satisfaction with democracy | Quantitative | 0: None–10: A lot |

| Will of the people | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| People’s decisions | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Differences elite—people | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Representation of ordinary citizen | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Politicians talk too much | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Consensus | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree | |

| Complicated politics | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Lack of worry | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Influence of vote | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Informed | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Disaffection | Quantitative | 0: No disaffection–10: A lot of disaffection |

| Interest in politics | Quantitative | 0: No interest–10: A lot of interest |

| Cultural elements | ||

| Multiculturalism–Immigration | Quantitative | 0: Multiculturalism–10: Immigration |

| Public services—Taxes | Quantitative | 0: Public services–10: Taxes |

| Freedom—Safety | Quantitative | 0: Freedom–10: Safety |

| Sexual freedom | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| European integration | Quantitative | 0: Strongly disagree–10: Strongly agree |

| Perceptive elements | ||

| Rating political leaders | Quantitative | 0: Very bad–10: Very good |

| Rating personal economic sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Rating current economic sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Rating prospective economic sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Rating current political sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Rating prospective political sit. | Quantitative | 0: Really bad–10: Really good |

| Ideological elements | ||

| Sympathy towards VOX | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Sympathy towards VOX 0: Other parties |

| Ideological self-placement | Quantitative | 0: Left–10: Right |

| Nationalist self-placement (Autonomous Communities) | Quantitative | 0: Minimal nationalism–10: Maximum nationalism |

| Spanish nationalist self-placement | Quantitative | 0: Minimal nationalism–10: Maximum nationalism |

| Spanish sentiment | Ordinal | 1: Only Spanish–5: Only from Autonomous Community |

| Independence | Nominal (dummy) | 1: Independence 0: Other issues |

| Media | ||

| Frequency of information monitoring in the media | Ordinal | 1: Never or hardly ever–6: Every day or most days |

| Social media information | Quantitative | 0: None–10: A lot |

| Social media participation | Quantitative | 0: None–10: A lot |

| Political landscape | ||

| Rating management of government and opposition | Quantitative | 0: Very bad–10: Very good |

| Rating inauguration | Quantitative | 0: Very bad–10: Very good |

| Rating coalition | Quantitative | 0: Very bad–10: Very good |

| 1 | For further reading on the terminological debate see: Jaráiz Gulías et al. (2020). |

| 2 | This is a computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) carried out between 14 January and 22 February 2020, with a sample size of 1000 units. The universe is comprised of a population over 18 years of age and residing in Spain and the sampling method is simple random sampling with proportional affixation according to sex and age quotas. The error for the sample +/− 3.1%, for a 95% level of trust and according to the principle of maximum indeterminacy p = q = 0.5. |

| 3 | In the April 2019 general election, VOX got 2,688,092 votes, which translates into a 10.26% of the valid votes and 24 seats, and in the November general election of the same year, they got 3,656,979 votes, a 15.08% of the valid votes and 52 seats, according to Spanish Ministry of Interior. |

| 4 | Table 3 shows the values of the odds ratio and the heterocedasticy-robust standard errors. |

| 5 | Table 4 shows the values of the odds ratio and the heterocedasticy-robust standard errors. |

| 6 | Degree of agreement with the statement ‘Through voting, people like me can influence what happens in politics’ and ‘Politicians talk a lot but do very little’, respectively. |

References

- Akkerman, Agnes, Cas Mudde, and Andrej Zaslove. 2014. How populist are the people? Measuring populist attitudes in voters. Comparative Political Studies 47: 1324–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladro, Eva, and Paula Requeijo. 2020. Discurso, estrategias e interacciones de Vox en su cuenta oficial de Instagram en las elecciones del 28-A. Derecha radical y redes sociales. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 77: 203–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Benavides, Antonio. 2019. Elementos para el análisis de una nueva extrema derecha española. In Movimientos Sociales, Acción Colectiva y Cambio Social en Perspectiva. Continuidades y Cambios en el Estudio de los Movimientos Sociales. Edited by Rubén Díez and Gomer Betancor. País Vasco: Fundación Betiko, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Armon-Jones, Claire. 1985. Prescription, Explication and the Social Construction of Emotion. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 15: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armon-Jones, Claire. 1986. The Thesis of Constructionism. In The Social Construction of Emotion. Edited by Rom Harré. Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell, pp. 32–56. [Google Scholar]

- Arter, David. 1992. Black Faces in the Blond Crowd: Populism Racialism in Scandinavia. Parliamentary Affairs 45: 357–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzheimer, Kai, and Elisabeth Carter. 2006. Political Opportunity Structures and Right-Wing Extremist Party Success. European Journal of Political Research 45: 419–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, James R. 1980. A Constructivism View of Emotion. In Theories of Emotions. Edited by Robert Plutchik and Henry Kellerman. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 305–39. [Google Scholar]

- Averill, James R. 2008. Together Again: Emotion and Intelligence Reconciled. In The Science of Emotional Intelligence: Knows and Unknowns. Edited by Gerald Matthews, Moshe Zeidner and Richard D. Roberts. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardez-Rodal, Asunción, Paula Requeijo, and Yanna G. Franco. 2020. Radical right parties and anti-feminist speech on Instagram: Vox and the 2019 Spanish general election. Party Politics 28: 272–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, Hans-Georg. 1990. Politics of Resentment. Right-wing Radicalism in West Germany. Comparative Politics 23: 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, Hans-Georg. 1994. Radical Right-Wing Populism in Western Europe. New York: McMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Betz, Hans-Georg. 2001. Exclusionary Populism in Austria, Italy and Switzerland. International Journal 56: 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, Hans-Georg, and Carol Johnson. 2004. Against de Current-Stemming the Tide: The Nostalgic Ideology of the Contemporary Radical Populist Right. Journal of Political Ideologies 9: 311–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bover, Olympia, and Pilar Velilla. 2005. Migrations in Spain: Historical background and current trends. In European Migration: What Do We Know? Edited by Klaus F. Zimmermann. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research, pp. 389–414. [Google Scholar]

- Brader, Ted. 2005. Striking a Responsive Chord: How Political Ads Motivate and Persuade Voters by Appealing to Emotions. American Journal of Political Science 49: 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Paloma, and Diego Mo. 2020. El issue de la inmigración en los votantes e VOX en las Elecciones Generales de noviembre de 2019. Revista de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas (RIPS) 19: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Paloma, and Erika Jaráiz. 2022. La construcción emocional de la extrema derecha en España. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS), in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cazorla, Ángel, and Erika Jaráiz. 2020. Componentes emocionales en el voto a la extrema derecha. In El auge de la extrema derecha en España. Edited by Erika Jaráiz, Ángel Cazorla and María Pereira. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch, pp. 227–58. [Google Scholar]

- De Bustillo, Rafael Muñoz, and José-Ignacio Antón. 2010. De la España que emigra a la España que acoge: Contexto, dimensión y características de la inmigración latinoamericana en España. América Latina Hoy 55: 15–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Jocelyn A. 2005. The Dynamics of Social Change in Radical Right-wing Populist Party Support. Comparative European Politics 3: 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felmand, Lisa. 2018. La vida secreta del cerebro. Cómo se construyen las emociones. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Fieschi, Catherine, and Paul Heywood. 2004. Trust, Cynicism and Populist Anti-politics. Journal of Political Ideologies 9: 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainsworth, Paul. 2008. The Extreme Right in Western Europe. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Chereyl. 2005. The Trouble with Passion. Political Theory beyond the Reign of Reason. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hogget, Paul, and Simon Thompson. 2012. Introduction. In Politics and the Emotions: The Affective Turn in Contemporary Political Studies. Edited by Paul Hogget and Simon Thompson. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2017. Trump and the xenophobic populist parties: The silent revolution in reverse. Perspectives on Politics 15: 443–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaráiz, Erika, Nieves Lagares, and María Pereira. 2020. Emociones y decisión de voto. Los componentes de voto en las elecciones generales de 2016 en España. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (REIS) 170: 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaráiz Gulías, Erika, Ángel Cazorla Martín, and María Pereira López. 2020. El auge de la extrema derecha en España. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch. [Google Scholar]

- Kitschelt, Herbert. 1995. The Radical Right in Western Europe: A Comparative Analysis. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lagares, Nieves, Ramón Máiz, and José Manuel Rivera. 2022. El régimen emocional del procés tras las elecciones catalanas de 2021. Revista Española de Ciencia Política 58: 19–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, Deborah. 1998. The Emotional Self: A Sociocultural Exploration. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lynggaard, Kennet. 2019. Methodological Challenges in the Study of Emotions in Politics and How to Deal with Them. Political Psychology 40: 1201–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, George E., Michael Mackuen, Jennifer Wolak, and Luke Keele. 2006. The Measure and Mismeasure of Emotion. In Feeling Politics: Emotion in Political Information Processing. Edited by David Redlawsk. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, George H. 1993. Espíritu, persona y sociedad. Paidós: Editorial Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, Mariana S., and James Dennison. 2021. Explaining the emergence of the radical right in Spain and Portugal: Salience, stigma and supply. West European Politics 4: 752–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, Ildefonso, and Isabel M. Cutillas. 2014. Has immigration affected Spanish presidential elections results? Journal of Population Economics 27: 135–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, Mihaela. 2014. Theorizing Agonistic Emotions. Parallax 20: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, Mihaela. 2016. Negative Emotions and Transitional Justice. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, José Ramón, Richard Gunther, Mariano Torcal, and Jesús Cuéllar. 1998. Actitudes hacia la democracia en España: Legitimidad, descontento y desafección. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (REIS) 83: 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2004. The Populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39: 541–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, Cas. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambidge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Oñate, Pablo, María Pereira, and Diego Mo. 2022. Emociones y voto a VOX en las elecciones de abril y noviembre de 2019 en España. Monográfico Emociones y Política. Revista Española de Ciencia Política (RECP) 58: 53–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, Pablo. 2018. The electoral breakthrough of the radical right in Spain: Correlates of electoral support for VOX in Andalusia (2018). Genealogy 3: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, Pablo. 2021. Organización partidista y rendimiento electoral. Una aproximación al caso de la derecha radical en España. Revista de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas (RIPS) 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlawsk, David P., ed. 2006. Feeling Politics. Emotion in Political Information Processing. London: Palgrave Macmillam. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, Guillem, Marc Guinjoan, and Eva Anduiza. 2017. The Emotional Underpinnings of Populism: How Anger and Fear Affect Populist Attitudes. Swiss Political Science Review 23: 444–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, José Manuel, Paloma Castro, and Diego Mo. 2021. Emociones y extrema derecha: El caso de VOX en Andalucía. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (REIS) 176: 119–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rydgren, Jens. 2003. Meso-Level Reasons for Racism and Xenophobia. Some Converging and Diverging Effects of Radical Right Populism in France and Sweden. European Journal of Social Theory 6: 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Denis G., and Roger D. Masters. 1988. “Happy Warriors”: Leaders Facial Display, Viewers Emotions, and Political Support. American Journal of Political Science 32: 345–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Political Leaders | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pablo Iglesias | Pedro Sánchez | Albert Rivera | Pablo Casado | Santiago Abascal | ||||||||||||

| Presence | Intensity | Permanence | Presence | Intensity | Permanence | Presence | Intensity | Permanence | Presence | Intensity | Permanence | Presence | Intensity | Permanence | ||

| Emotions | Pride | 28.8% | 4.00 | 68.8% | 27.4% | 3.46 | 94.1% | 75.7% | 4.59 | 100.0% | ||||||

| Fear | 72.6% | 4.50 | 100.0% | 62.2% | 4.38 | 100.0% | 3.1% | 4.00 | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 3.5% | 3.33 | 100.0% | ||

| Hope | 58.9% | 3.37 | 28.4% | 56.0% | 3.39 | 90.7% | 93.4% | 4.50 | 98.3% | |||||||

| Anxiety | 40.6% | 4.61 | 100.0% | 30.6% | 4.00 | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 3.5% | 2.89 | 100.0% | |||

| Enthusiasm | 32.2% | 3.73 | 36.2% | 24.7% | 3.45 | 100.0% | 74.1% | 4.14 | 100.0% | |||||||

| Anger | 65.3% | 4.51 | 100.0% | 67.4% | 4.31 | 100.0% | 8.2% | 3.29 | 61.4% | 8.2% | 3.69 | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | ||

| Hate | 23.8% | 4.20 | 100.0% | 24.2% | 4.34 | 93.3% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | ||||

| Contempt | 40.6% | 4.21 | 100.0% | 49.1% | 4.18 | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | ||||

| Worry | 82.5% | 4.59 | 100.0% | 88.1% | 4.46 | 98.2% | 6.7% | 2.70 | 23.3% | 10.0% | 3.16 | 83.9% | 5.1% | 3.31 | 68.9% | |

| Peace of mind | 32.1% | 3.90 | 68.1% | 37.8% | 3.60 | 90.7% | 77.1% | 4.26 | 100.0% | |||||||

| Resentment | 19.9% | 4.37 | 100.0% | 27.2% | 3.94 | 88.7% | 3.5% | 4.56 | 100.0% | 3.6% | 3.00 | 44.3% | 1.6% | 100.0% | ||

| Bitterness | 24.6% | 4.20 | 100.0% | 22.1% | 3.93 | 100.0% | 3.1% | 4.50 | 100.0% | 3.1% | 3.01 | 50.5% | 1.6% | 100.0% | ||

| Disgust | 35.5% | 4.14 | 100.0% | 39.7% | 3.88 | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | 1.6% | 100.0% | ||||

| Political Parties | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PODEMOS | PSOE | C’s | PP | VOX | ||||||||||||

| Presence | Intensity | Permanence | Presence | Intensity | Permanence | Presence | Intensity | Permanence | Presence | Intensity | Permanence | Presence | Intensity | Permanence | ||

| Emotions | Pride | 3.2% | 4.00 | 49.9% | 25.0% | 3.58 | 85.8% | 23.5% | 4.11 | 36.5% | 72.2% | 4.52 | 100.0% | |||

| Fear | 62.4% | 4.72 | 100.0% | 46.8% | 4.37 | 96.6% | 2.0% | 3.00 | 100.0% | |||||||

| Hope | 6.7% | 2.47 | 58.1% | 3.22 | 63.3% | 67.0% | 3.52 | 70.3% | 91.8% | 4.42 | 98.3% | |||||

| Anxiety | 36.7% | 4.73 | 100.0% | 20.3% | 3.95 | 100.0% | 1.6% | 3.00 | 1.5% | 100.0% | 2.0% | 2.00 | 100.0% | |||

| Enthusiasm | 3.5% | 2.45 | 31.0% | 3.23 | 52.6% | 37.6% | 3.33 | 59.3% | 74.9% | 4.11 | 100.0% | |||||

| Anger | 65.2% | 4.59 | 100.0% | 63.2% | 4.50 | 100.0% | 3.5% | 4.11 | 100.0% | 15.2% | 4.08 | 76.6% | ||||

| Hate | 19.9% | 4.92 | 100.0% | 11.9% | 4.59 | 87.2% | 2.0% | 5.00 | 100.0% | |||||||

| Contempt | 33.6% | 4.49 | 100.0% | 19.0% | 4.31 | 100.0% | 3.5% | 4.56 | 56.2% | |||||||

| Worry | 78.5% | 4.55 | 100.0% | 73.5% | 4.52 | 100.0% | 1.6% | 3.00 | 100.0% | 7.0% | 3.95 | 100.0% | 3.5% | 3.34 | 100.0% | |

| Peace of mind | 3.2% | 3.50 | 32.5% | 3.58 | 84.2% | 47.0% | 3.51 | 69.3% | 75.5% | 4.12 | 100.0% | |||||

| Resentment | 18.7% | 5.00 | 100.0% | 23.8% | 4.45 | 100.0% | 2.0% | 5.00 | 100.0% | 5.4% | 3.44 | 100.0% | ||||

| Bitterness | 19.9% | 4.92 | 100.0% | 20.3% | 4.58 | 100.0% | 3.5% | 5.00 | 55.3% | |||||||

| Disgust | 33.4% | 4.45 | 100.0% | 23.3% | 4.00 | 100.0% | 2.0% | 5.00 | 100.0% | |||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic and contextual | ||||||

| Gender | 2.629 ** (0.327) | 2.299 * (0.411) | ||||

| Catholics | 3.468 ** (0.439) | |||||

| Rating current political sit. | 0.711 ** (0.148) | 0.799 * (0.090) | ||||

| Rating prospective political sit. | 0.805 * (0.132) | |||||

| Attitudinal, issues and post-materialist values | ||||||

| Ideological self-placement | 2.313 *** (0.101) | 2.527 *** (0.099) | 2.663 *** (0.106) | 1.801 ** (0.137) | 1.735 ** (0.243) | |

| Independence | 5.491 *** (0.411) | 7.698 *** (0.394) | 9.673 *** (0.434) | 6.226 *** (0.489) | 10.236 ** (0.675) | |

| Satisfaction with democracy | 0.814 ** (0.080) | 0.857 * (0.080) | ||||

| Disaffection | ||||||

| Complicated politics | 0.863 * (0.070) | 0.823 ** (0.072) | ||||

| Lack of worry | 1.177 * (0.076) | 1.225 ** (0.082) | ||||

| Influence of vote | 0.804 ** (0.061) | 0.774 *** (0.068) | 0.837 * (0.077) | |||

| Populism | ||||||

| Representation of ordinary citizen | 1.126 * (0.057) | |||||

| Leadership | ||||||

| Rating Santiago Abascal | 2.032 *** (0.105) | |||||

| Rating Pablo Casado | 0.611 ** (0.155) | 0.686 * (0.157) | ||||

| Rating Albert Rivera | 0.768 * (0.098) | |||||

| Rating Pablo Iglesias | 0.747 ** (0.088) | 0.653 ** (0.139) | ||||

| Sympathy and emotions | ||||||

| Sympathy towards VOX | 39.251 *** (0.761) | |||||

| Hope for Abascal | 40.564 ** (0.903) | |||||

| Enthusiasm for Casado | 0.095 ** (0.845) | |||||

| Enthusiasm for C’s | 0.235 * (0.670) | |||||

| Anger towards PSOE | 3.583 * (0.587) | |||||

| Constant | 0.108 *** (0.510) | 0.002 *** (0.797) | 0.001 *** (1.039) | 0.000 *** (1.064) | 0.007 *** (0.965) | 0.002 *** (1.153) |

| Nagelkerke | 29.0% | 54.7% | 56.8% | 59.5% | 70.8% | 80.8% |

| % Correct | 91.4 | 93.9 | 95.3 | 95.1 | 96.7 | 97.0 |

| % Correctly predicted VOX observations | 0.0 | 47.3 | 58.2 | 56.9 | 75.0 | 77.8 |

| % Correctly predicted Other parties observations | 100.0 | 98.1 | 98.7 | 98.4 | 98.7 | 98.7 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural elements | |||||

| Level of studies | 0.817 * (0.092) | 0.809 * (0.100) | |||

| Income level | 1.173 ** (0.060) | 1.244 *** (0.067) | 1.375 *** (0.073) | 1.306 ** (0.100) | |

| Catholics | 4.644 *** (0.261) | 4.229 *** (0.272) | 2.311 ** (0.298) | ||

| Attitudes towards politics and institutions | |||||

| Trust in democratic institutions | 0.917 * (0.045) | ||||

| Will of the people | 0.831 *** (0.051) | ||||

| Politicians talk too much | 1.155 ** (0.052) | ||||

| Politics as complicated | 0.931 * (0.034) | ||||

| Influence of voting | 0.916 ** (0.034) | 0.908 * (0.040) | 0.864 ** (0.055) | 0.900 * (0.054) | |

| Cultural elements | |||||

| Multiculturalism—Immigration | 1.256 *** (0.046) | 1.202 ** (0.067) | |||

| Public services—Taxes | 1.170 ** (0.053) | ||||

| Freedom—Safety | 1.296 *** (0.060) | ||||

| Sexual freedom | 0.746 *** (0.060) | 0.722 *** (0.078) | 0.779 ** (0.020) | ||

| Perceptive elements | |||||

| Rating Santiago Abascal | 2.198 *** (0.080) | 1.899 *** (0.078) | |||

| Rating Pedro Sánchez | 0.742 *** (0.102) | 0.757 *** (0.068) | |||

| Rating Pablo Iglesias | 0.818 * (0.101) | ||||

| Ideological elements | |||||

| Ideological self-placement | 1.646 *** (0.133) | ||||

| Sympathy towards VOX | 10.802 *** (0.569) | ||||

| Constant | 0.062 *** (0.568) | 0.282 (0.896) | 0.020 (0.938 ***) | 0.136 *** (1.151) | −3.508 ** (0.867) |

| Nagelkerke | 10.2% | 17.8% | 35.9% | 71.3% | 73.4% |

| % Correct | 84.7 | 84.8 | 86.5 | 92.7 | 93.7 |

| % Correctly predicted VOX observations | 0.0 | 5.5 | 25.4 | 68.0 | 72.4 |

| % Correctly predicted Other parties observations | 100.0 | 99.2 | 97.0 | 97.1 | 97.4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jaráiz Gulías, E.; Castro Martínez, P.; Colomé García, G. The Emotional Dimension of the Spanish Far Right and Its Effects on Satisfaction with Democracy. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100475

Jaráiz Gulías E, Castro Martínez P, Colomé García G. The Emotional Dimension of the Spanish Far Right and Its Effects on Satisfaction with Democracy. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):475. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100475

Chicago/Turabian StyleJaráiz Gulías, Erika, Paloma Castro Martínez, and Gabriel Colomé García. 2022. "The Emotional Dimension of the Spanish Far Right and Its Effects on Satisfaction with Democracy" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100475

APA StyleJaráiz Gulías, E., Castro Martínez, P., & Colomé García, G. (2022). The Emotional Dimension of the Spanish Far Right and Its Effects on Satisfaction with Democracy. Social Sciences, 11(10), 475. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100475